Abstract

Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care and support are provided to adolescents living with HIV, with the aim to build safer sex negotiation skills, sexual readiness and reproductive preparedness while reducing unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. We consider how different settings might either constrain or facilitate access to resources and support. Ethnographic research was conducted in Malawi in teen club clinic sessions at an enhanced antiretroviral clinic from November 2018 to June 2019. Twenty-one individual and five group interviews were conducted with young people, caregivers, and healthcare workers, and were digitally recorded, transcribed, and translated into English for thematic analysis. Drawing on socio-ecological and resilience theories, we considered the different ways in which homes, schools, teen club clinics, and community settings all functioned as interactional, relational, and transformational spaces to allow young people to talk about and receive information on sexuality and health. Young people perceived that comprehensive SRH support enhanced their knowledge, sexual readiness, and reproductive preparedness. However, their desire to reproduce at an early age complicated their adoption of safer sex negotiation skills and SRH care. Engaging and talking about SRH and related issues varied according to physical and social space, suggesting the value of multiple locations for support and resources for young people with HIV.

Résumé

Des soins et un soutien de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR) sont prodigués aux adolescents vivant avec le VIH pour renforcer leurs compétences de négociation permettant des rapports sexuels plus sûrs et pour les préparer à la vie sexuelle et à la procréation, tout en réduisant les grossesses non désirées et les infections sexuellement transmissibles. Nous examinons comment différents contextes peuvent limiter ou faciliter l’accès aux ressources et au soutien. Une recherche ethnographique a été menée au Malawi pendant des séances d’un club d’adolescents dans un centre de traitement antirétroviral renforcé de novembre 2018 à juin 2019. Vingt et un entretiens individuels et cinq entretiens en groupe ont été réalisés avec des jeunes, des soignants et des agents de santé; ils ont été enregistrés numériquement, transcrits et traduits en anglais pour faire l’objet d’une analyse thématique. Nous fondant sur les théories socio-écologiques et de résilience, nous avons examiné les différentes façons dont les contextes à la maison, à l’école, dans les clubs d’adolescents des centres de santé et dans la communauté fonctionnaient tous comme espaces interactionnels, relationnels et transformationnels pour permettre aux jeunes de parler de la sexualité et de la santé et de recevoir des informations sur ces questions. Les jeunes estimaient qu’un appui complet de SSR améliorait leurs connaissances, les préparait à la sexualité et à la procréation. Néanmoins, leur souhait d’avoir des enfants à un âge précoce compliquait leur adoption de compétences de négociation permettant des relations sexuelles plus sûres et des soins de SSR. Les jeunes vivant avec le VIH s’impliquaient et parlaient de la SSR et des questions apparentées différemment selon l’espace physique et social où ils se trouvaient, dénotant l’utilité de leur apporter un soutien et des ressources dans de multiples lieux.

Resumen

Se brindan servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) y apoyo a adolescentes que viven con VIH, a fin de desarrollar sus habilidades para la negociación de sexo más seguro, su preparación sexual y su preparación reproductiva, y a la vez reducir los embarazos no intencionales y las infecciones de transmisión sexual. Consideramos cómo diferentes contextos podrían restringir o facilitar el acceso a recursos y apoyo. Se realizó una investigación etnográfica en Malaui durante sesiones de clínicas de clubes de adolescentes en una clínica de antirretrovirales mejorados, entre noviembre de 2018 y junio de 2019. Se realizaron 21 entrevistas individuales y cinco entrevistas en grupo con jóvenes, cuidadores y trabajadores de salud. Esas entrevistas fueron grabadas digitalmente, transcritas y traducidas al inglés para análisis temático. Basándonos en teorías de socio-ecología y resiliencia, consideramos las diferentes maneras en que hogares, escuelas, clínicas de clubes de adolescentes y ámbitos comunitarios funcionaban como espacios interaccionales, relacionales y transformacionales para permitirles a las personas jóvenes hablar sobre sexualidad y salud y recibir información al respecto. La juventud percibió que el apoyo integral en SSR mejoró sus conocimientos, su preparación sexual y su preparación reproductiva. Sin embargo, su deseo de procrear a temprana edad complicó su adopción de habilidades para la negociación de sexo más seguro y los servicios de SSR. La participación y conversaciones sobre SSR y asuntos afines variaron según el espacio físico y social, lo cual indica el valor de tener múltiples locales para brindar apoyo y recursos a jóvenes con VIH.

Introduction

Different spaces – private and public, formal and informal, personal and professional – and different actors including parents/caregivers, health care providers, teachers, and peers, all affect the everyday lives of young people, their access to resources and, in the context of HIV, their capacity for resilience.Citation1 Diverse settings, including home, work, school, and “third places”, such as parks, other community settings, and virtual sites, enable different kinds of dialogue, influencing what might be discussed and with whom. The mix of settings, we suggest, enables experiential learning, engagement, and empowerment.Citation2

Spaces are “permeated with social relations”,Citation3 meanings and experiences that are (re)produced and supported by social relations. Defining a place “as space with a purpose, includ(ing) physical spaces, people, programmes and representations” can be “interpreted, narrated, perceived, felt, understood and imagined”.Citation4 Places also provide space for experiential learning that is sensitive, stimulating and informative too.Citation5,Citation6 In this article, we focus on “spaces and places” as contested environments in which heterogeneous, multiple, and fluid interrelationships are explored.Citation2,Citation7 Boundaries of space and their multi-layered influences, at individual, relational, social, cultural, and structural levels, on intimacy and sexual matters contribute to how sexual and reproductive health (SRH) might best be prioritised specifically for adolescents living with HIV.Citation8,Citation9 Understanding how different spaces and places are used can illuminate broader issues of health and wellbeing.

Discussing sexuality in the home is not the norm in Malawi, and fear of household tension tends to silence young people.Citation10,Citation11 Providing “safe spaces” in communities and schools, as alternative venues for them to discuss sex and sexuality, can help redress misinformation regarding SRH, and counter inequality and social exclusion.Citation12,Citation13 Our focus is on the importance of “where” – the places and spaces that make SRH issues visible, and so create supportive and ideally inclusive environments.Citation14 Treating physical spaces as static or restrictive tends to constrain service use delivery for people living with HIVCitation14–16 and arguably, limits wider discussions of sexuality. We see space as “permeated with social relations”Citation3 that are (re)produced and supported through continued interactions. We define place “as space with a purpose, including physical, social spaces, people, programmes and representations” which can be “interpreted, narrated, perceived, felt and imagined”.Citation4 Places provide opportunities for experiential learning that is, for our purpose, sensitive, stimulating, and informative to adolescents.Citation5,Citation6 Individual and collective participation across settings can enable relationships that illuminate issues concerning SRH, care, and wellbeing.

Malawi’s current population is 17.9 million, with a median age of 17 years. Malawi has among the highest rates of early marriages in Africa: by age 15, 9% of girls are married and 42% by 18; among boys, 1% are married by 15 and 6% by 18.Citation17,Citation18 Young women are at particular risk for poor SRH outcomes due to high HIV prevalence, poverty, orphanhood, early sexual debut and early marriage and early age at first birth (5% by 15 years, 12% by 16 years).Citation19 Of all people acquiring HIV in 2019, 29% were young people aged 15–24.Citation20

The Differentiated Service Delivery (DSD) policy framework was introduced in 2016 in a number of low- and middle-income countries, including Malawi, as part of a programmatic shift to improve HIV care delivery and outcomes.Citation21,Citation22 This led to the introduction of dedicated physical spaces and clinics for ART care.Citation23 DSD, also known as differentiated care, is a client-centred approach that simplifies and adapts HIV care to reflect the needs and preferences of young people living with HIV to reduce burdens on the health system.Citation23,Citation24 DSD emphasises the who (clinician, lay providers, peers, clients), the what (clinical assessment, antiretroviral therapy (ART) refill, viral load, and monitoring), the where (i.e. health care facility, community, home) and the when (monthly, every 2, 3, or 6 months).Citation22,Citation25

In Malawi, the teen club clinic (hereafter TCC) was developed to support young people who had acquired HIV either vertically or horizontally. This clinic is a youth- or child-friendly space with dedicated physical spaces, visit days, and the provision of multi-month antiretroviral treatment (ART) to ensure adherence.Citation23,Citation26,Citation27 Once every two months, the clinic brings together from 20 to 90 young men and women living with HIV; in addition, it provides psychosocial support and SRH education through lectures, counselling, peer discussions, role-playing, and group discussions for age-specific groups (10–14, 15–17, and 18–19 years). Topics include treatment adherence, relationships, pregnancy, substance use, gender-based violence, and entrepreneurship. In this article, we move beyond this clinical space to consider the capacity of different adolescent-caregiver-health worker spaces, retreats, and workshops to consider factors that impact access to services designed to support adolescent wellbeing.

Many spaces provided for young people are gendered and closed (male or female only), isolating individuals and problematising equitable access to care.Citation13 For instance, rites of passage held prior to puberty for boys and around menarche for girls have historically supported sexual preparedness and parenthood,Citation18,Citation21 including through different forms of initiation. The value placed on early reproduction during adolescence and religious ideas about contraception, promoted in these contexts and more widely in the community, generate barriers to contraceptive use. How different spaces within homes and communities support positive dialogue on SRH-related matters is often overlooked.Citation22 Different personal, physical, and social spaces enable learning and afford “therapeutic or transformative” health outcomes in ways that accommodate local individual and institutional differences.Citation28–30 The TCCs were established and operate on this premise but, as we describe, their role is complemented formally and informally within the community to enable SRH positive outcomes.

Methods

Ethnographic research was conducted by the first author as a volunteer with the TCC from November 2018 to June 2019, with adolescents aged 15–19 years who attended the antiretroviral clinic of the Umodzi Family Center (UFC) and the TCC at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. The UFC is part of the regional and national HIV response for enhanced service delivery, training, and mentorship. The centre, which is identified as a Centre of Excellence (CoE) of the Lighthouse Trust, was chosen because it is adolescent-centred. It monitors and provides comprehensive integrated HIV services, including prevention, care, and treatment, TB screening and management, and referral for patients with advanced HIV.Citation9,Citation11,Citation31 The first author had volunteered in the programme since 2014,Citation11 and this provided her with insight into the complexities facing adolescents with regard to informed choices, communication, physical satisfaction, sexual readiness, and reproductive preparedness.

The research explored with whom, where and how young people discussed sex, sexual interests, and intimate relationships, and where they went for treatment and care when they were sick, had concerns, or wished to access contraceptives. To gain a deeper understanding of the contexts of communication, we included semi-formal spaces where young people interacted with peers and others. The first author is a social scientist with a background in sociology and medical anthropology, with over 10 years experience as a qualitative researcher. She conducted all individual interviews and moderated focus group sessions, with a mixed team of research assistants living openly with and without HIV. A few selected adolescents acted as research assistants and played a key role in providing feedback during dissemination and advisory panel meetings.

Study participants

Fifty-four study participants were purposively selected. They included 26 adolescents, most of whom had acquired HIV at birth, and had joined the TCC when they were between 8–10 years old after disclosing their HIV status to significant others, which from the point of view of the TCC, signalled their acceptance of HIV diagnosis and its implications. Additional participants included 21 caregivers/guardians identified by adolescents as Persons Most Knowledgeable about their lives, and seven health workers and mentors who delivered TCC programmes. These included all clinical staff who were mentors and played multiple roles at the TCC, and non-clinical persons such as adolescents who had adhered to treatment, were retained in the TCC, and mentored younger people to live positively. Assent for adolescents aged 15–17 (minors) was sought for study participation, with consent from a parent or caregiver. Adolescents aged 18–19, parents/guardians, and health workers provided written and verbal consent. Research conformed to ethics and human research guidelines and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (M180465, dated 04 May 2018) and the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC)- (P.04/18/2389, dated 03 July 2018) in Malawi.

Data collection

Data collection methods included participant observation, in-depth interviews (IDIs), and focus group discussions (FGDs). Participant observation was used for an extended period as a means of engaging and participating with varied communities, health, and social systems to gather nuanced and in-depth experiences on sensitive topics involving adolescents and their caregivers.Citation32–34 This included attendance at TCC preparatory meetings (from one to eight hours) on Wednesdays and Saturdays, including guardian sessions, workshops, and retreats. These sessions provided familiarity with TCC programmes scheduled monthly and yearly. Through this approach, the first author developed informal relationships with young people, which enabled casual discussions on adolescent romance, partnered behaviours, pregnancy, and contraceptive use. Topic guides for interviews and focus groups were developed with 42 adolescents attending a similar TCC in a second district, about 70 km from Blantyre, and were discussed with advisory panel members. The advisory panel informed research study processes and ensured contextual relevance and validity across the study site.Citation31

In-depth interviews provided insight into individual SRH-related experiences and needs. Interviews with adolescents were held face-to-face, at a place of their choice, including in a temporary office at the clinic, school grounds, or home. Interviews ranged from 30–90 min, were digitally voice recorded, and were conducted in Chichewa (vernacular) and English; all participants preferred to express themselves in a mix of languages. Interviews were also conducted with healthcare workers (7) and caregivers (21) to elicit their perspectives on adolescents’ SRH practices and support.

Group discussions were used for triangulation purposes and ensured richness of the data. The first author attended 15 extra routine group sessions held on a quarterly basis as workshops at the clinic. These were facilitated by health workers and local and national mentors, to enhance health worker and parent–child interactions and to support understandings of the experiences of young people in relation to maturity, sexuality, contraception and relationships, and initiation ceremonies at church and in the community. Observational notes were taken at these workshops. An additional six workshops, organised as part of the research study, were held at weekends for health workers, adolescents and caregivers/parents for learning, reflections and enhanced support. Topics and resource support during these workshops varied, ranging from: good adherence leadership, guardian-parent orientations, and sessions on how to improve the adolescents’ lives, social, and entrepreneurial skills. Other sessions were held with mentors and young people identified as role models with whom TCC members could relate.

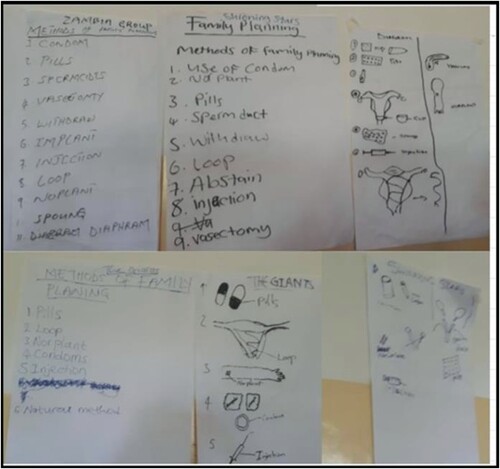

The first author used an observation guide and checklist to explore and document how adolescents and health workers formulated scenarios on SRH, and participated in role plays on the importance of staying in school, on STI/HIV care, and on how TCC staff could facilitate SRH care services and support. Observations were conducted in health education classes too, where either health workers or young people were able to ask questions and used various approaches (such as drawings and maps) to depict resources, people, and institutions that supported their SRH-related needs. These different settings provided rich data on SRH-related experiences.Citation5,Citation35 Research participants and tools are described in .

Table 1. Summary of research participants and tools.

Data analysis

Preliminary analysis occurred concurrently with data collection to enable iteration. All digitally voice-recorded IDIs, FGDs, and workshops were transcribed verbatim, translated by research assistants, and imported into NVivo 11 software for coding. The first author checked all translations of notes and transcripts and worked with research assistants when revision was needed. The first author familiarised herself with the data; undertook initial coding and developed sub-themes; and discussed the themes with mentors and adolescents to ensure depth in analysis.Citation36 The results were shared with the co-authors, health workers, and mentors. Broader themes and sub-themes were also discussed in different sessions (in one-to-one interviews, group, and feedback sessions). The iterative analytical process enabled us to add emerging themes, identify new connections, and develop more in-depth formulations.

The broad themes included: SRH talks, knowledge, needs, desires, preparedness, readiness, sexual function, and physical, social, and transformational spaces. Codes identified included physical spaces (homes, schools, health facilities) and social settings (churches, communities). The TCC, rites, and ceremonies were included as transformational places. Workshops with health workers, mentors, and caregivers assisted with iteration and interpretation, allowing constant discussion and comparison of themes during reflective moments and feedback sessions. Although anonymity could not be ensured in focus groups, pseudonyms were assigned to maintain data security and confidentiality.

Results

Sexual information, learning, and sharing

Adolescents responded on SRH knowledge, choices, pleasure, desires, and partnered behaviour. Younger adolescents (aged 15–17, n = 12, 8 females, 4 males) were open to talking about friendships, abstinence, sex-related issues, and condoms, and although they were at times awkward, they occasionally asked direct questions: “When is the best time to have sex?” (IDI, male, 16 years old). Older adolescents (aged 18–19, n = 14, 7 males, 7 females) talked freely about partnering, service use, and how different spaces provided opportunities to share information, make informed decisions about sexual desire, marriage, and reproduction, and described places that were conducive for intimacy. Healthcare workers (n = 7, 4 females and 3 males) and caregivers (n = 17, 12 females and 5 males, including teachers n = 4, 3 females and 1 male) were involved in one-to-one interview sessions and group counselling, health education, comprehensive sexual health, and feedback sessions in multiple places including the HIV clinic, the TCC and its various activities, and at school, home, church and community.

SRH and “perceptions of innocence”

Talking about sex, with whom, when to start preparing, or when one was ready for sex, evoked mixed emotions during interviews. Physical spaces such as bedrooms, spare rooms, and backyards in homes provided caregivers, adolescents, and peers with privacy to discuss sensitive topics. This proved important because of continued stigma and misinformation. Caregivers who were the biological parents of adolescents often found it challenging to disclose to their child that their HIV was transmitted vertically:

“It is difficult … to tell my child that I am the one who exposed him to HIV. I need him to be careful out there. For me being a parent as well as a guardian, I am supposed to enlighten the child.” (IDI, mother, 43 years old)

Caregivers saw young children as sexually innocent and were reluctant to talk to them about sex and condoms; instead, they emphasised the value of abstinence and the importance of both young women and men remaining chaste until marriage. At the same time, most people knowledgeable about adolescents’ lives claimed that they encouraged an “open door and open communication”, reflecting TCC clinic advice and feedback sessions which were designed to empower them to initiate conversations with their children about sex and sexuality. Almost all parents saw their homes as protective places for care and relational support, but also as spaces that provided constraint and overview:

“When my child comes back from school, he stays at home. I do not see a lot of girls coming to visit him. … so, I feel like maybe when girls want to come, they think twice to do so, because of me. My son is protected in our home space.” (FGD, mixed group of parents)

Understanding intimacy

Adolescents aged 15–17 talked freely about visiting each other in their homes, meeting at school, and spending time with others, often as friends rather than intimate partners. In FGDs, most adolescents repeated morally laden discourses which emphasised staying safe and “remaining sexually pure” to protect themselves from the negative consequences of early sex and early motherhood. A few reported that they had little experience and were reluctant to join in group discussions about sex and sexuality, while others referred to “self-love”, “sexual preparedness”, and the value of having the choice of when and with whom to have sex. Some participants emphasised their education and reaching certain educational goals: “You have five friends and all of them are asking you, why are you still a virgin, this and that? … I keep on pushing. I want to achieve. It is just a choice” (IDI, Simbe, male, 16-year-old).

Participants aged 18–19 provided rich accounts in FGDs and IDIs of sexual responsibility and intimate relationships. Peers reinforced each other’s knowledge on questions about sex and sexuality, casual and intense romantic relationships, sharing ideas about sex and contraception. Neither young men nor young women differentiated between romance (forming bonds, attachments, sharing values, and interests) and sexual relationships. Adolescents referred to “romantic” relationships as involving hugging, kissing, talking in person and on the phone, and being together in public and private spaces. Some adolescents created their own private spaces to be together and to have sex, paving the way for experiential learning. These spaces included parents’ and friends’ homes, servants' or housemaid quarters (“boy’s quarters”), hostels (places which provide cheap lodging for a specific group of people such as students), hotels, guesthouses, and city parks:

“Maybe the boy might have a friend and that friend of his has a house, and you might be able to go and meet at his friend’s house … for an adolescent to be involved in sex, it is also dependent on peer pressure, for instance, I stay at the hostel … (there) … we also open up and encourage each other as boys” (FGD, males, 19-year-olds).

Young people considered that different sites enable them to explore questions of intimacy and engaging in “safe sex”. Although the TCC was a clinical intervention with monthly meetings for health education and support, adolescents saw it also as a place at which to nurture romantic relationships; they made it their own “special meeting space”. Meeting and having fun in groups in secluded areas, close to trees or bushes, allowed young people opportunities for intimacy. Young men saw local parks as cheap places to be, which allowed them privacy to relax away from the public gaze. Young women, on the other hand, were anxious about being in public, and some were uncomfortable spending time with young men in secluded areas. Young women and men both lacked confidence negotiating consistent condom use, despite TCC support. Particularly when they booked into hotels or guest houses, they expected their partner to be responsible for contraception, but in addition, some young women rejected contraception because they were worried that this would affect their ability to conceive later.

Communication in schools

Adolescents, parents/caregivers, and health workers were ambivalent about schools providing comprehensive SRH knowledge and skills. Adolescents emphasised that schools were a “safe space” within which teachers encouraged friendship, peer learning, and nurtured life skills, where girls were encouraged to continue their education, and where they were able to ask questions about sex, abstinence, and contraception. Health workers regarded the comprehensive life skills syllabus in primary and secondary schools as enabling both genders to learn about puberty, reproduction, sexuality, and enhanced life goals. There were criticisms, however. Some participants argued that because pregnant girls, and boys involved in substance use, had been expelled from school, schools exacerbated social exclusion. Others, particularly health workers and adolescents, were unhappy with depictions in textbooks of people living with HIV as sickly and sad, and they bemoaned the stigma around HIV:

“With the current life skills syllabus in school, primary or secondary, adolescents living with HIV hear contradictory information and they ask questions, ‘What do HIV people look like? They develop sores on the skin, they lose weight’. Such statements disturb adolescents.” (IDI, female, mentor, 19 years old)

Community rites and religious meetings

Most parents, caregivers, and health workers referred to rites of passage that occurred in cultural, religious, and community contexts and were a hallmark of adolescence, and observed that the content of these was evolving. They saw these as nurturing a sense of belonging, the development of moral values, and supporting sexual identity and pleasure, and that they were important for the wellbeing of adolescents. These programmes were led by senior community members, with content varying by geographic area, age of participants, and religion. Most female caregivers referred to the need to develop new content and “new” ways of delivering such ceremonies, particularly in urban areas where, due to migration and tribal inter-marriage, initiation rites were not as strong as in rural areas.

Ceremonies associated with rites of passage tended to be held in religious and community settings on demand, as retreats at the church or at a designated recreational place, over weekends, and during school holidays, with separate spaces for each gender. In some communities, rites were week-long, held in the city in family homes for privacy, or in rural areas in temporary shelters of grass and sticks (initiation huts), which were burnt to the ground once the young participants had returned home. Young men emphasised the importance of undergoing circumcision at a private or mobile clinic, and they expected their fathers to support them to learn how to “become” men. Young women spoke of the value of community gatherings to learn how to enhance sexual function and satisfaction, to continue culturally informed practices such as labia elongation, and to learn about penetrative sex:

“Some say that in our generation, it is meaningless to go to the initiation huts. And sometimes we hear that, [a young woman] has been divorced because she did not have this and that [elongated labia] … and the marriage ended. … So, we are under pressure and we start asking parents [preparing ourselves] … friends will advise you to attend the initiation ceremony … ” (FGD, girls, 18–19 years old)

“We do not prohibit them from circumcision … because it is their personal choice, we tell them that they might go for circumcision … but we enlighten them and emphasize that it does not mean that, if they might have sex with a person, they might not become more vulnerable and be exposed to infections including HIV.” (FGD, fathers, 38–45 years old)

Adolescent-centred SRH talks at teen club sessions

In talks at teen club sessions, adolescents indicated their desire to be in relationships with HIV-positive peers, and their conversations centred on initiating sex and the possibility of having a child who was HIV-negative when both partners were HIV-positive. All adolescents were open about their status and spoke of the challenge this presented:

“I do not think about relationships, even marriage. I am already sick (i.e. HIV). I do not think any man would like to marry dirt.” (IDI, Gala, female, 17 years old)

“I know myself, I am living with HIV, and when I visit my girlfriend, I do not wish her to get pregnant. I do not wish to have a child now.” (IDI, Viwe, male, 18 years old)

Discussion

While some young men and women living with HIV were romantically involved and/or sexually active, those <18 years were likely to report no sexual experience. As noted, adolescents utilised secluded public and private spaces for sex and romantic moments, away from adult surveillance: they associated these spaces with sexual subjectivity, defined as feelings of sexual self-efficacy, pleasure, self-reflection, and worth,Citation35 including the ability, in theory, to negotiate contraception or condom use. This contrasts with other studies which emphasise adolescent girls visiting hotels, inns, and motels for prostitution or transactional sex,Citation37,Citation38 which paid little attention to the sexuality of young men.Citation39

Most adolescents in romantic or sexual relationships appreciated having a potential partner attending the TCC, because they felt that, as a result, there was no need for them to disclose their status, or to broach questions of HIV testing, viral load testing, or having safe sex. Adolescents aspired to have children born without HIV and were eager to know how to ensure their babies would be born negative, and they were generally confident to question this and to seek clarification about viral load and safe sex. Breaking the culture of silence on SRH issues, ensuring discussions around sexuality and reproduction at the TCC and at school, enhanced resilience.Citation40

By involving them in the TCC and by follow-up visits from health workers to adolescents’ homes, the protective roles of parents and caregivers were addressed, and this encouraged intergenerational support. This is rarely considered in the literature on adolescent SRH.Citation14,Citation41,Citation42 While caregivers challenged positive discourses on sex and sexuality developed for adolescents,Citation9,Citation43 the TCC helped them to maintain an active role in supporting adolescent sexuality and empowerment among those for whom they cared. Persons most knowledgeable about adolescents’ lives, such as caregivers, feared repeated exposure to HIV and were reluctant to affirm their children’s readiness for parenthood and its complications, but this is not consistent with the literature that uses rights-based and utilitarian approaches which emphasise parental support of young people in relation to sexuality.Citation6,Citation44 Different spaces in adolescent SRH have the potential to provide comprehensive support from multiple settings. Both health workers and parents/caregivers reiterated the need for the school syllabus to be more inclusive, to provide images of adolescents living positively, and among young people, to enhance knowledge about sexuality, and to promote their ability to make informed decisions about sexual readiness, contraception, and reproduction.

Rites of passage ceremonies in religious settings and within communities suggest the value of including culturally meaningful ways for adolescents to engage with different people in different spaces for SRH education. Most parents talked to their children first and then referred them to community-based initiation ceremonies and churches for further moral education. There is reported ambivalence regarding the role of rites of passages in promoting sex rather than abstinence for young people,Citation18,Citation45,Citation46 but in this research, community and church programmes, for those adolescents who attended them, affirmed cultural pride and the normality of being sexual active, strengthening their preparedness for sex and parenthood, and enhancing their self-esteem and, ultimately, resilience.

The TCC addressed inequality by providing free access to SRH, HIV care, and treatment services, and mitigated potential social exclusion by providing food and transport reimbursement. Adolescents accessing the TCC were empowered to question and link medical knowledge to inform decision-making. Through the role of health providers including mentors, nurses, and clinicians,Citation5,Citation47 the TCC fostered resilience by providing counselling and comprehensive health education, supporting the retention of adolescents on ART programmes,Citation9 and assisting HIV-negative adolescents to access contraception and antenatal care.Citation8 This is consistent with most DREAMS (Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored, and Safe) studiesCitation48 that have emphasised the provision of “safe spaces and service supports” for adolescents’ holistic wellbeing.Citation49,Citation50 The DREAMS initiative centres on interventions that reduce the impact of structural drivers, such as HIV risk, poverty, gender inequality, sexual violence, and lack of education, so as to promote health and social outcomes among young women and their male partners.Citation48 Participatory spaces, retreats, workshops, and clinic programmes combine to empower vulnerable young people. Young people also regarded TCC spaces as an important source of SRH-related information, which raised their awareness of positive concepts around sexual health, empowerment, and satisfaction.

Strengths and limitations

By working with adolescents, health workers, and caregivers/parents, we ensured diverse perspectives. While SRH issues are sensitive, and respondents may have felt obliged to adjust their views, exposure to questions around HIV and sex at the TCC likely ensured that they were comfortable participating in the study. Most young people attending TCC had been enrolled at the age of eight and continued to learn as they interacted with peers and health care providers. The age of participants might have influenced their recall of behaviours, understandings of what was being asked, and responses, particularly when reminded of abusive moments such as sexual and physical abuse within sexual relations and emotional abuse between adolescents and their caregivers. Most accounts of abusive relationships were referred to nurses who were trusted, had expertise, and had provided care to adolescents for more than five years, offering day-to-day compassion, care, and psychosocial support. Sexual diversity was not addressed, and the assumption in the TCC was of heteronormative sexuality. We did not quantify sexual and reproductive service use outcomes (e.g. number of those who had ever had sex, adolescents using STI care, family planning, ever been pregnant); these are presented elsewhere.Citation51 Most participants were living with perinatally-acquired HIV, and this analysis may not be generalised to adolescents without HIV.

Conclusion

Adolescents had access to multiple enabling learning spaces and a range of persons to support their health and wellbeing. With caregivers and health workers, they initiated conversations on sex, sexual pleasure, function, friendship, and contraception, spoke relatively candidly, and asked questions that enhanced their engagement and increased their confidence to request support. Although different spaces and actors potentially have quite different effects across stages of adolescence, each space provides new opportunities for adolescents to make informed choices. This broad approach contributes to our understanding of SRH care are as multi-dimensional, age-dependent, interconnected, and continuous.

Ethics and consent

Research conformed and followed all ethics and human research guidelines. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (M180465) on 4 May 2018 and the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC)- (P.04/18/2389) on 3 July 2023 in Malawi. Written, informed, and verbal consent were obtained from all participants during data collection. All responses and study locations were anonymised.

Author contributions

BNKK conceptualised the paper, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. AM and LM gave inputs on the conceptualisation, analysis, and writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Acknowledgements

BNKK benefited from the TCC class of 2018, UFC staff, Marvellous, and the support of Professor Don Mathanga, Dr Atupele Kapito-Tembo, Chikondi Khofi, and the team at MAC-CDAC.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pols J. Analyzing social spaces : relational citizenship for patients leaving mental health care institutions. Med Anthropol. 2016;35(2):177–192. doi:10.1080/01459740.2015.1101101.

- Abbott-Chapman J, Robertson M. Youth leisure, places, spaces and identity. In: Gammon S, Elkington S, editors. Landscapes of leisure space, place and identities. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015. p. 123–134.

- Lefebvre H, Nicholson-Smith D. The production of space. Vol. 142. Oxford: Blackwell; 1991. p. 1–464.

- Abbott-Chapman J, Robertson M. Adolescents’ favourite places: redefining the boundaries between private and public space. Sp Cult. 2009;12(4):419–434.

- Skovdal M, Belton S. The social determinants of health as they relate to children and youth growing up with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;45:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.024.

- Svanemyr J, Amin A, Robles OJ, et al. Creating an enabling environment for adolescent sexual and reproductive health : A framework and promising approaches. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56(1):S7–S14. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.011.

- Massey D. For space. London: SAGE; 2005. p. 1–117.

- Callahan T, Modi S, Swanson J, et al. Pregnant adolescents living with HIV: what we know, what we need to know, where we need to go. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):1–4. Available from: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction = viewrecord&from = export&id = L620216007%0A. http://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.1.21858.

- Kaunda-Khangamwa BN, Kapwata P, Malisita K, et al. Adolescents living with HIV, complex needs and resilience in Blantyre, Malawi. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):35. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00292-1.

- Mwalabu G, Evans C, Redsell S. Factors influencing the experience of sexual and reproductive healthcare for female adolescents with perinatally-acquired HIV: a qualitative case study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):125.

- Kaunda-Khangamwa BN. A volunteer for life: interactions in resilience and service-use research in Malawi. Med Anthropol Theory. 2020;7(2):671–686.

- Adegoke CO, Steyn MG. A photo voice perspective on factors contributing to the resilience of HIV positive Yoruba adolescent girls in Nigeria. J Adolesc. 2017;56:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.01.003.

- Jones N, Pincock K, Baird S, et al. Intersecting inequalities, gender and adolescent health in Ethiopia. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):97.

- Weszkalnys G. Review: the anthropology of space and place : locating culture by Setha M. Low and Denise Lawrence-Zúñiga. Cambridge J Anthropol. 2004;24(3):96–98.

- Meer T, Müller A. They treat us like we’re not there: queer bodies and the social production of healthcare spaces. Health Place. 2017;45(March):92–98. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.010.

- World Health Organisation. WHO recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. 2018.

- UNICEF Malawi. Budget scoping on programmes and interventions to “End child marriage in Malawi.” Lilongwe: UNICEF Malawi; 2019. p. 1–48.

- Makwemba M, Chinsinga B, Kantukule CT, et al. Survey Report: Traditional Practices in Malawi. Zomba, Malawi; 2019.

- Muula A, Lusinje AC, Chetimila P, and Prisca M. Youth clubs' contributions towards promotion of sexual and reproductive health services in machinga district, Malawi. Tanzania Journal of Health Research. 2015;17(3):1–9. doi:10.4314/thrb.v17i3.6.

- National AIDS Commission. Malawi National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS 2020 – 2025 sustaining gains and accelerating progress towards epidemic control. Lilongwe, Malawi: National AIDS Commission; 2020. p. 1–140.

- Armstrong A, Nagata JM, Vicari M, et al. A global research agenda for adolescents living with HIV. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(Supplement 1):S16–S21.

- Reif LK, Mcnairy ML, Lamb MR. Youth-friendly services and differentiated models of care are needed to improve outcomes for young people living with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(3):249–256.

- MacKenzie RK, van Lettow M, Gondwe C, et al. Greater retention in care among adolescents on antiretroviral treatment accessing “Teen Club” an adolescent-centred differentiated care model compared with standard of care: a nested case-control study at a tertiary referral hospital in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(3):e25028. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002jia2.25028%0Ahttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29178197%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid = PMC5810310.

- World Health Organisation. The importance of sexual and reproductive health and rights to prevent HIV in adolescent girls and young women in eastern and southern Africa. Evidence Brief. (No. WHO/RHR/17.05) [Internet]. Geneva; 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255334/WHO-RHR-17.05-eng.pdf.

- Armstrong EL, Boyd RN, Kentish MJ, et al. Effects of a training programme of functional electrical stimulation (FES) powered cycling, recreational cycling and goal-directed exercise training on children with cerebral palsy: a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e024881. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002central/CN-01958141/full.

- Global AIDS Update. Seizing the moment: tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2020; p. 1–384. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf.

- Prust ML, Banda CK, Callahan K, et al. Patient and health worker experiences of differentiated models of care for stable HIV patients in Malawi: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):1–15.

- Munthali A, Zulu E. The timing and role of initiation rites in preparing young people for adolescence and responsible sexual and reproductive behaviour in Malawi. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;11(3):150–167.

- Kearns R, Milligan C. Placing therapeutic landscape as theoretical development in health & place. Heal Place. 2020;61(December 2019):102224. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102224.

- Thamuku M, Daniel M. The use of rites of passage in strengthening the psychosocial wellbeing of orphaned children in Botswana. African J AIDS Res. 2012;11(3):215–224.

- Kaunda-Khangamwa BN, Maposa I, Dambe R, et al. Validating a child youth resilience measurement (CYRM-28) for adolescents living With HIV (ALHIV) in urban Malawi. Front Psychol. 2020;11(August):1–13.

- Nanfuka EK, Kyaddondo D, Ssali SN, et al. Social capital and resilience among people living on antiretroviral therapy in resource- poor Uganda. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):1–21.

- Stake RE. Sample chapter: multiple case study analysis. In: Multiple case study analysis. New York: Guilford Publications; 2006. p. 1–16.

- Wray N, Markovic M, Manderson L. “Researcher saturation”: The impact of data triangulation and intensive-research practices on the researcher and qualitative research process. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1392–1402.

- Boislard M-A, van de Bongardt D, Blais M. Sexuality (and lack thereof) in adolescence and early adulthood: a review of the literature. Behav Sci (Basel). 2016;6(1):8. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/6/1/8.

- Srivastava A, Thomson BS. Framework analysis : a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. JOAAG. 2009;4(2):72–79.

- Addison D, Baim-Lance A, Suchman L, et al. Factors influencing the successful implementation of HIV linkage and retention interventions in healthcare agencies across New York State. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(0123456789):105–114. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2060-2.

- Krisch M, Averdijk M, Valdebenito S, et al. Sex trade among youth: a global review of the prevalence, contexts and correlates of transactional sex among the general population of youth. Adolesc Res Rev. 2019;4(2):115–134. doi:10.1007/s40894-019-00107-z.

- Izugbara CO, Undie CC. Masculinity scripts and the sexual vulnerability of male youth in Malawi. Int J Sex Heal. 2008;20(4):281–294.

- Skovdal M, Daniel M. Resilience through participation and coping-enabling social environments: the case of HIV-affected children in sub-Saharan Africa. African J AIDS Res. 2012;11(3):153–164. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.298916085906.2012.734975.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Lane C, Wong S. What does not work in adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A review of evidence on interventions commonly accepted as best practices. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2015;3(3):1–9.

- Woodgate RL, Zurba M, Edwards M, et al. The embodied spaces of children with complex care needs : effects on the social realities and power negotiations of families. Health Place. 2017;46(August 2016):6–12. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.001.

- Fielden SJ, Chapman GE, Cadell S. Managing stigma in adolescent HIV : silence, secrets and sanctioned spaces. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(3):267–281.

- World Health Organisation. Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. Guidance to support country implementation. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2017; p. 1–176. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/framework-accelerated-action/en/.

- Feyisetan B, Munthali A, Benevides R, et al. Evaluation of youth-friendly services in Malawi. Washington (DC): USAID; 2014; p. 1–190. Available from: http://www.e2aproject.org/publications-tools/pdfs/evaluation-yfhs-malawi.pdf.

- Jimmy-Gama DB. An assessment of the capacity of facility-based youth friendly reproductive health services to promote sexual and reproductive health among unmarried adolescents: Evidence from rural Malawi [Internet]. PhD Thesis. Queen Magret; 2009. Available from: http://ethesis.gmu.ac.uk.

- Theron LC. Community-researcher liaisons: the pathways to resilience project advisory panel. South African J Educ VO - 33. 2013;33(4):1–19. Available from: https://login.ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/login?auth=shibb&url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edssci&AN=edssci.S0256.01002013000400004&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Saul J, Bachman G, Allen S, et al. The DREAMS core package of interventions: a comprehensive approach to preventing HIV among adolescent girls and young women. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208167–e0208167. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T = JS&PAGE = reference&D = med15&NEWS = N&AN = 30532210.

- Fleischman J, Peck K. Addressing HIV risk in adolescent girls and young women. A report of the CSIS global health policy center. Washington (DC): Centre for Strategic and International Studies; p. 1–24. 2015; Available from: http://csis.org/files/publication/150410_Fleischman_HIVAdolescentGirls_Web.pdf.

- World Health Organisation. Engaging young people for health and sustainable development: strategic opportunities for the World Health Organization and partners. Geneva; 2018; p. 1–61. Available from: https://www.who.int/life-course/publications/engaging-young-people-for-health-and-sustainable-development/en/.

- Kaunda-Khangamwa BN, Maposa I, Phiri M, et al. Service use and resilience among adolescents living with HIV in Blantyre, Malawi. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(4):11. doi:10.5334/ijic.5538.