Abstract

Pleasure is often left out of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) interventions. The expanding evidence base suggests that the inclusion of pleasure can improve SRHR outcomes and increase safer sex practices. However, there is a lack of research into how to include pleasure in applied SRHR work, particularly outside of key groups. This study aims to present the experiences of a cohort of pleasure implementers and develop a series of implementation best practices. Data were gathered from a structured survey filled out by pleasure implementers (n = 8) twice between September 2021 and October 2022 at 6-month intervals. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out remotely with pleasure implementers, those that funded their pleasure work (n = 2) or provided technical support (n = 2) in January 2023. Pleasure implementers, based in Central, East and Southern Africa and India, reported tangible outcomes of their pleasure-based work in various contexts and across diverse groups. Themes that emerged from analysis of the FGDs and survey responses included pleasure as a portal to positive outcomes, barriers to a pleasure approach, and mechanisms by which pleasure allows for open and non-judgmental discussion about sex and pleasure. A series of best practices emerged from pleasure implementer experiences. This study concludes that a pleasure-based approach can be introduced to a wide range of groups and communities, even those assumed too conservative to accept a pleasure approach. The best practices developed offer a range of practically driven recommendations, that others can lean on when integrating a pleasure approach into their work.

Résumé

Le plaisir est souvent laissé de côté dans les interventions de santé et droits sexuels et reproductifs (SDSR). La base croissante de données suggère que l’inclusion du plaisir peut améliorer les résultats en matière de SDSR et favoriser les pratiques sexuelles sûres. Néanmoins, on observe un manque de recherche sur la manière d’inclure le plaisir dans le travail appliqué en matière de SDSR, en particulier en dehors des groupes clés. Cette étude vise à présenter les expériences d’une cohorte d’intégrateurs du plaisir et à élaborer une série de bonnes pratiques de mise en œuvre. Les données ont été recueillies à partir d’une enquête structurée remplie par des intégrateurs du plaisir (n = 8) deux fois entre septembre 2021 et octobre 2022 à des intervalles de six mois. En janvier 2023, des discussions de groupe ont été organisées à distance avec les intégrateurs du plaisir, les personnes qui finançaient leur travail en matière de plaisir (n = 2) ou apportaient un soutien technique (n = 2). Les intégrateurs du plaisir, basés en Afrique centrale, orientale et australe ainsi qu’en Inde, ont fait état de résultats concrets de leur travail fondé sur le plaisir dans différents contextes et au sein de groupes divers. Les thèmes qui ont émergé de l’analyse des discussions de groupe et des réponses à l’enquête comprenaient le plaisir comme portail vers des résultats positifs, les obstacles à une approche du plaisir et les mécanismes par lesquels le plaisir permet une discussion ouverte et sans jugement sur les rapports sexuels et le plaisir. Une série de bonnes pratiques a émergé des expériences des intégrateurs du plaisir. Cette étude conclut qu’une approche basée sur le plaisir peut être introduite dans un vaste éventail de communautés et de groupes, même ceux qui sont considérés comme trop conservateurs pour accepter une telle approche. Les bonnes pratiques mises au point offrent une palette de recommandations concrètes, sur lesquelles d’autres peuvent s’appuyer pour intégrer une approche axée sur le plaisir dans leur travail.

Resumen

Generalmente se omite el placer en las intervenciones sobre salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR). La creciente base de evidencia indica que la inclusión del placer puede mejorar los resultados de SDSR y aumentar las prácticas de sexo más seguro. Sin embargo, se carece de investigaciones sobre cómo incluir el placer en el trabajo aplicado en SDSR, en particular fuera de grupos clave. Este estudio pretende presentar las experiencias de una cohorte de ejecutores de placer y crear una serie de prácticas óptimas de ejecución. Se recolectaron datos por medio de una encuesta estructurada contestada por ejecutores de placer (n = 8) dos veces entre septiembre de 2021 y octubre de 2022 a intervalos de 6 meses. Se realizaron discusiones en grupos focales (DGF) a distancia con ejecutores de placer, aquellos que financiaron su trabajo sobre placer (n = 2) o brindaron apoyo técnico (n = 2) en enero de 2023. Los ejecutores de placer, con sede en África Central, Occidental y Meridional y en India, informaron resultados tangibles de su trabajo sobre placer en diversos contextos y en diversos grupos. Entre los temas que surgieron del análisis de las DGF y las respuestas a las encuestas se encuentran: placer como un portal a resultados positivos, barreras al enfoque de placer, y mecanismos por los cuales el placer permite un debate abierto y sin prejuicios sobre sexo y placer. De las experiencias de los ejecutores de placer surgió una serie de prácticas óptimas. Este estudio concluye que el enfoque basado en placer se puede presentar a una gran variedad de grupos y comunidades, incluso aquellos que son considerados como demasiado conservadores para aceptar el enfoque de placer. Las prácticas óptimas elaboradas ofrecen una variedad de recomendaciones prácticas, que otras personas pueden seguir para integrar el enfoque de placer en su trabajo.

Plain language summary

Sexual pleasure is often not included in programmes that try to improve sexual and reproductive health. It is important to include sexual pleasure here as there is evidence that it is good for people’s physical and mental health, and it can help people to practice safer sex, such as using condoms more regularly. We don’t know very much about how to best introduce people to sexual and reproductive health programmes that include sexual pleasure. This study tries to understand how a group of people that included sexual pleasure in their programmes did this and what they thought were the best ways to do this, we call these best practices. We asked this group of people about their experiences of including sexual pleasure using a survey and by asking them in a group discussion. They told us that those people introduced sexual pleasure programmes to feel more self-confident and more able to practice safer sex. They also told us that they came across challenges such as people feeling shame around sexual pleasure. The best practices that we present in this study can help guide people who want to include sexual pleasure in their sexual and reproductive health programmes. The best practices include advice on how to speak about sexual pleasure to people, how to train the people that will introduce sexual pleasure programmes to others, and how those that fund sexual pleasure programmes can help.

Introduction

This paper seeks to understand the impact of a round of funding, specifically for implementation of pleasure-based work, granted by AmplifyChange in collaboration with The Pleasure Project. Considering the benefits of including pleasure in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) interventions,Citation1 this study explores experiences of pleasure implementers and the funding partnership, in applying a pleasure approach in different contexts and in a diverse range of groups.

Background

Pleasure is pertinent

Pleasure is often overlooked as an important aspect of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), despite it being a key driver for why people have sex,Citation20,Citation22 and despite sexual and reproductive rights being core building blocks to being able to experience and express sexual pleasure.Citation2 In recent years our understanding of pleasure has expanded as being central not only to SRHR, but also mental health, physical health and our general wellbeing.Citation3–5 Evidence for the benefit of including pleasure in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) interventions is also emerging, with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis finding that pleasure-incorporating interventions increased condom use.Citation1 However, pleasure-incorporating interventions were mainly found in STI/HIV prevention, rather than contraception or family planning programming, and were aimed at those deemed high risk, such as men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM).Citation1 It is also worth noting that a “pleasure gap” has been identified which suggests that, overall, SRH interventions insufficiently address pleasure and continue to focus on negative SRH outcomes.Citation5,Citation6 An earlier review also found that eroticising safer sex led to less risky sexual practices.Citation7 More recently, data from the German Sexuality and Health Survey showed that sexual pleasure was associated with more indicators of good sexual health in women.Citation21 This work builds on earlier, more theoretical work about the inclusion of pleasure in SRHR (see, for exampleCitation8–11). Currently, there is a lack of research that aims to understand how to include pleasure into applied SRHR work,Citation11 and arguably this is the next step. There is some limited evidence on pleasure work happening “on the ground”, for example, an analysis of the implementation of pleasure-positive sex education in Kenya and GhanaCitation12 and a group randomised control trial of pleasure-positive HIV prevention group education for Black women in the USA.Citation13 A feasibility and initial efficacy study of an online pleasure-positive HIV prevention intervention for MSM is an example of the small evidence base on online pleasure-positive interventions,Citation14 as is a digital campaign to introduce pleasure-based SRHR to young adults across Africa on TikTok, Instagram and Twitter.Citation15 However, much of this work, both in-situ and online, is not formally documented and evaluated. Recent implementation principles, The Pleasure Principles, will help to guide work that takes a “pleasure approach” going forward.Citation16 A pleasure approach addresses SRH with a pleasure-based and pleasure-positive approach.

A pleasure partnership: funding pleasure

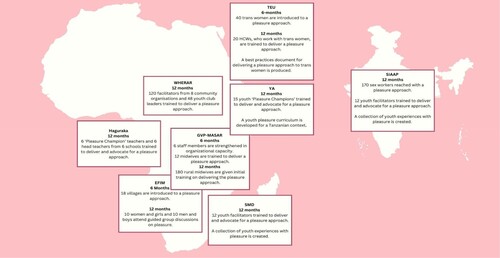

AmplifyChange and the Pleasure Project came together in formal partnership in 2021 with the ambition to fund and support AmplifyChange grantees to implement pleasure-based SRH. AmplifyChange is a fund that supports civil society organisations that advocate for improved SRHR. The Pleasure Project is an international education and advocacy organisation which advocates for a pleasure-positive approach to SRHR. The Case for Her provided funding for a top-up pleasure grant to AmplifyChange grantees, technical support from The Pleasure Project and project management. To initiate this project AmplifyChange invited all current grantee partners to attend a webinar on a pleasure approach, led by The Pleasure Project. From here grantee partners were invited to apply for a top-up grant to fund the addition and/or integration of pleasure work into their existing projects. AmplifyChange and The Pleasure Project came together to assess 16 incoming grant applications based on creativity, motivation to learn, feasibility and how they incorporated pleasure into their work. Eight pleasure implementers were offered pleasure top-up grants based on their proposals (see ). These eight pleasure implementers then received additional training from The Pleasure Project via webinars and had one-on-one sessions with The Pleasure Project team and AmplifyChange’s Grant Support Team members to refine their proposals. AmplifyChange managed the grants, collected progress reports and measured impacts and The Pleasure Project continued to provide technical support.

Table 1. Pleasure implementers and pleasure approach activities

Objectives

This paper aims to report on the experiences of a cohort of organisations (n = 8) who have implemented pleasure interventions after receiving a grant specifically to fund pleasure work. We aim to elucidate how pleasure is understood by implementers, and the challenges and successes they face. We also seek to understand the experiences of AmplifyChange and The Pleasure Project, to understand experiences of supporting and funding pleasure work. We aim to develop a series of best practices for integrating a pleasure approach into SRHR programming.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not sought for this project because data were collected as part of a service evaluation. All participants provided informed verbal consent for participating in the FGD data collection activity and for their data to be reported. All participants provided informed written consent for their data, collected through the structured survey, to be reported.

Methods

This qualitative study aimed to document and understand the experiences of those receiving and coordinating a grant for implementing a pleasure approach via two qualitative data collection techniques: qualitative surveys and FGDs. Participants were pleasure implementers (n = 8), those that funded their pleasure work (n = 2) and those that provided technical support (n = 2). Pleasure implementers also collected grant impact indicators which are reported in this paper. It should be noted that pleasure implementers were obliged to fill in the qualitative surveys as part of the grant monitoring process but participation in the FGDs was voluntary. The researcher who carried out the FGDs and led the data analysis was external from AmplifyChange and the Pleasure Project, who coordinated the grant monitoring process.

Qualitative survey data collection

Eight pleasure implementers were asked to fill in a structured qualitative survey (see Appendix 1) about their experience of implementing pleasure at two intervals during the period of implementation. Surveys were collected as a routine part of reporting to AmplifyChange on grant activities. All surveys were shared and filled in digitally. The survey asked pleasure implementers to reflect on the challenges and successes of their projects at 6-month and 12-month intervals and consisted of questions with free text response boxes. Surveys were filled out between September 2021 and October 2022. The surveys were filled out by the pleasure implementer organisations collaboratively, in teams, or by individual spokespeople. All the pleasure implementers filled out the survey, in detail, at both 6 and 12 months. Six pleasure implementers filled in the survey in English and two filled in the survey in French. Where surveys were filled in in French, they were translated by a member of the research team before analysis.

Analysis of qualitative survey content

The content of the surveys was analysed using inductive thematic analysis.Citation17 Survey content was read and re-read by RM, and emerging themes were documented until saturation was reached. A theme was considered emergent when several data points that related could be grouped together. Themes were organised under larger umbrella themes to add structure to the analysis.

RM also used deductive coding techniques to draw out best practices. This was considered deductive coding as data points that described pragmatic techniques for implementing a pleasure approach were actively sought out. These data points were coded under best practices and then further inductively analysed to draw out emergent best practices.

Emergent themes and best practices from survey analysis were shared with the authorship team on one occasion to check for agreement, refine and develop the themes collaboratively.

Focus group discussion data collection

FGDs were carried out with all pleasure implementers to add depth, clarify and sense-check the themes and best practices emerging from the qualitative survey analysis. FGDs were carried out using an online meeting software. RM, an experienced qualitative researcher trained in FGD facilitation, facilitated the FGDs. Verbal informed consent was gathered at the beginning of each FGD. A semi-structured FGD guide was used. The FGD guide was developed in response to the outcome of survey content analysis and included open-ended questions related to emergent themes. A discussion stimulus sheet was also developed and used in the FGDs. This stimulus sheet presented emergent best practices to pleasure implementers to spark discussion on the appropriateness and accuracy of emergent best practices. The discussion guide and stimulus were developed collaboratively by the authorship team, who consisted of pleasure, public health, and qualitative research experts. Three FGDs were carried out in two groups of three pleasure implementers in English and one group of two pleasure implementers in French. The FGD carried out in French included two pleasure implementers, an English-speaking researcher and a French-speaking member of the authorship team who provided translation support. FGDs were held in January 2023.

A fourth FGD was carried out in January 2023 by RM with two representatives from the Pleasure Project and two from AmplifyChange to elicit understanding of implementing pleasure from an organisational and funder perspective. An adapted semi-structured FGD guide and FGD stimulus was used in this FGD. FGDs were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Focus group discussion analysis and analysis synthesis

Transcripts of FGDs were inductively analysed by RM and emerging themes were documented until saturation was reached. Data points were added to existing themes which emerged from the survey analysis, and new themes arose from the FGD analysis.

RM also used deductive coding techniques to draw out further FGD data on each existing best practice. Data points that added depth to existing best practices were sought out. Data points describing pragmatic techniques for implementing a pleasure approach were also sought out to check for new emergent best practices in the FGD data.

Emergent themes and best practices from FGD analysis, were shared with the authorship team on one occasion to check for agreement, refine and develop the themes collaboratively.

Themes and best practices from both the survey and FGD qualitative analyses were brought together and synthesised into an integrated analysis. Themes from both activities were mapped using an online whiteboard tool. We looked for where themes across both analyses expressed the same sentiment, were related, challenged each other, or where the FGD analysis added depth or clarification to the themes and best practices that emerged from the survey analysis.

Routine grant impact indicator collection

As part of the pleasure work grants, organisations were asked to select one indicator from a set of pre-existing AmplifyChange indicators, specifically adapted to measure pleasure-inclusive work. Grantee partners were then asked to develop milestones and means of verification associated with this work and report on them every six months (see Appendix 2). Pleasure implementers routinely collected their pleasure activities and recorded the number of people they reached with pleasure activities and any tangible outcomes of the project. Grant impact indicators were collected between September 2021 and October 2022. Grant impact indicators are presented in this paper as reported by pleasure implementors.

Results

Measuring pleasure: pleasure impact indicators

Grantees measured pleasure, in their own way (see Appendix 2), and described tangible outcomes of their project. It is important to note that these outcomes cannot speak to pleasure’s impact on key SRHR outcomes, but rather speak to tangible pleasure impacts (e.g. number of people reached with a pleasure approach) within specific communities or groups ().

What did pleasure implementers say: qualitative findings

Pleasure portals

It emerged from the integrated analysis that a pleasure approach could be thought of as a portal; it opened access to positive outcomes due to engagement with a pleasure approach.

A pleasure approach as a portal to joy

The joy that was experienced because of engaging with pleasure was evident in the data, both verbally and through tone of voice. Pleasure implementers described laughter and giggling during pleasure approach activities.

“Lots of, you know, giggling sounds, they enjoyed and even the facilitators enjoyed the session because they kind of share their own experiences.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

A pleasure approach as a portal to self-confidence

Pleasure implementers spoke of how a pleasure approach taught people to understand their bodies, their right to pleasure, and how to communicate their needs and boundaries.

“Most girls will find that they think that when a boy forces them to have sex, it’s difficult for them to say, no, I don’t want this … But during the discussions were able to talk about the importance of being clear to what you want and what you don’t want.” (Pleasure Implementer 2, FGD)

“Once you know what you want from a relationship – transactional or romantic, then it increases your power.” (Pleasure Implementer 3, Survey)

A pleasure approach as a portal to SRH and wellbeing

Pleasure implementers described that self-confidence, communication, and openness around sex were linked to safer sex.

“But if there is communication, if there is talking, if there is consent, and if there is wider opening about sex, at least with partners, it’s easier for them to have choices of having safe sex.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

Case Study 1: Learning how to have better sex with sex workers in India

Through group discussion and sharing of pleasure tips, sex workers developed ways of experiencing more pleasure.

Safe self-pleasure

Sex workers described really enjoying masturbation. Safe masturbation tips, like using lubes that are safe (coconut oil rather than yoghurt) and keeping fingernails short to avoid scratches, were shared.

Lube for all!

The importance of lube was recognised in the group discussions. SIAAP also reported that some sex workers experienced more pleasurable sex when they were menstruating which provided an all-natural lube.

Fun with condoms

SIAAP told us that some sex workers had more pleasurable sex when they used a condom, as they felt less anxious about their sexual health. Sex workers also liked to use ribbed, dotted and flavoured condoms so safer sex was more fun for them and their clients. Fun condoms also gave them a bit more leverage when it came to negotiating condom use.

Forgetting about guilt and shame

Some sex workers reported to SIAAP that approaching sex from a pleasure perspective helped them to forget about the guilt and shame they felt around sex and enjoy sex more.

More pleasure = More profit

A pleasure approach enhanced sex workers earnings, SIAPP reported that sex workers told them they were earning more after being introduced to a pleasure approach.

“[We spoke about] topics like premature ejaculation, which for so many young sexually active men, has been contributed by the fear-based sex education.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

A pleasure approach as a portal to facilitator wellbeing and pleasure

Through facilitating a pleasure approach, pleasure implementers became more comfortable and confident talking openly about pleasure, got in touch with their own sense of pleasure and boosted their confidence.

“I can even openly talk about masturbation. I can even talk openly about using dildo. It’s something we never used to talk about, right? … [Now] I feel comfortable telling people this is the type that I use. So, it gives me confidence day to day, and I just enjoy talking about it.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

“They are keen on understanding their own sexuality … and really deepen their understanding about their own sexual pleasure and they’re able to share this with the sex workers.” (Pleasure Implementer 4, FGD)

What is stopping us? Barriers to a pleasure approach

Pleasure implementers discussed barriers and challenges to implementing a pleasure approach. Some of these barriers were evident across contexts, and some were more context-specific.

Shame and fear as a barrier to a pleasure approach

Across all pleasure implementers shame and fear around sexual pleasure was highlighted as a key barrier.

“Some youth still fear disclosing their sexual desires … They feel they will be judged if they open up about topics such as what gives them pleasure during sex.” (Pleasure Implementer 2, FGD)

“People fear to talk about it because they feel like they’ll be associated with doing it.” (Pleasure Implementer 5, FGD)

Case Study 2: Call the midwife … to talk about pleasure

GVP-MASAR told us that, in the DRC, if a woman talks about sex, she is a target for criticism and stigma. In this context, training midwives to integrate a pleasure approach into antenatal visits with women, was perceived as challenging to say the least! Heterosexual cis women in contexts like the DRC are often considered out of reach for pleasure work due to this stigma that GVP-MASAR describes. GVP-MASAR describe midwives’ involvement in the project as “spontaneous”, which was “surprising”. Midwives, especially in urban areas, took to delivering a pleasure approach with relative ease and the women they spoke to, began to speak out about their experiences of sex and pleasure, encouraging those around them to do the same.

Gender norms and misogyny as a barrier to a pleasure approach

Gender norms and misogyny were highlighted as a barrier to achieving pleasure, particularly for women in heterosexual relationships.

“A woman in most cases has to make sure that her husband is satisfied and content, while on the flip side of the coin the same emphasis tends to be lost on men.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

“In our culture, when we are together, as you, you’ll find that boys are more open when discussing issues of sex. But the girls, they become more shy. They basically think males are the one who has a say.” (Pleasure Implementer 5, FGD)

“Stereotypes related to issues on sex and relationship between, you know, men and women. And it’s just a platform to really unpack them, to talk them out between individuals and to also address them as well. So, it really provides that kind of a platform to chat about these gender stereotypes.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

How does a pleasure approach work? Pleasure mechanisms

Analysis of this data revealed mechanisms by which a pleasure approach may work to achieve positive outcomes and overcome barriers (e.g. Case Study 3).

Case Study 3: Choosing the right stimulation

SIAPP told us that they used clips from Tamil cinema which helped open up discussion (along with facilitators and sex workers singing along). EFIM told us that using video clips in their context, working with communities in the DRC, was unthinkable. Not only is there little access to electricity in the villages EFIM work in, making having a monitor or a TV difficult, but video clips could be misconceived as propaganda (due to historic use of videos for this purpose). Instead, EFIM used participatory theatre techniques to engage people.

Pleasure mechanism: granularity

A pleasure approach operates by talking about sex and sexuality in a more granular way, by speaking about the building blocks of sex and sexuality. An example of this is a group conversation about erogenous zones with young people in Lesotho. Rather than presenting sex as an opaque phenomenon, the pleasure implementers revealed its granularity by asking “what feels good?”.

“Body touches [gestures to different body parts] … can also lead to enjoyment.” (Pleasure Implementer 2, FGD)

“We can also approach gender and sexuality in terms of touch, sensation, and pleasure.” (see Case Study 4).

Case Study 4: Coming out as pleasure-positive in Tanzania

Homosexuality is highly stigmatised in Tanzania and sex between people of the same sex is criminalised. In this context, YA told us that a pleasure approach is a tool for understanding diversity of sexuality. YA told us that a pleasure approach initiates understanding of diversity due to discussion of where people like to be touched, how they like to be touched and who they like to be touched by. These pleasure building blocks lay the foundation for young people to appreciate diversity of sexualities, both in others and themselves.

Pleasure mechanism: bonding and engagement

Pleasure implementers described how talking about pleasure was enjoyable to people and helped them to engage with pleasure and an SRH discourse.

“They enjoy talking about it. And when even the discussion is over, people are like 'can we extend?' - they need more time.” (Pleasure Implementer 1, FGD)

“This pleasure topic made them active, actively participate and share their experiences and that also created a better bond among them.” (Pleasure Implementer 4, FGD)

Table 2. Best practice table - “Let's Do It!”

Pleasure takeaways: discussion

This paper found tangible impacts that showed the reach of a “pleasure approach” across a diverse range of contexts, SRHR delivery modalities, civil society organisations and social groups. Pleasure implementer experiences revealed the joy and laughter that a pleasure approach can encourage. Pleasure implementers spoke about how a pleasure approach ensures open communication on sex and pleasure, ensuring good communication skills and self-confidence. They describe how this can be important for people in discussing consent and navigating safer sex practices with partners. There is evidence that echoes this link between communication skills and safer sex.Citation7,Citation18 The facilitators of a pleasure approach also experienced their own joy and increases in self-confidence. This allowed some facilitators to feel confident in being vulnerable with their own pleasure experiences. In turn, this modelled vulnerability and openness to those engaging with a pleasure approach.

Shame was described as a key barrier to a pleasure approach, as often reported with SRH interventions.Citation3,Citation9 Pleasure implementers acknowledged the presence of shame within groups and individuals and shared practices for overcoming this barrier, such as constructing a safe space in which to discuss pleasure and sex. Pleasure implementers also suggest that we cannot assume which individuals will feel shame and will be unwilling to discuss pleasure; shame cannot be mapped on to certain individuals or groups based on stereotypes and assumptions. Misogyny was highlighted as a barrier to women experiencing pleasure and misogynistic constructions of gender were revealed in pleasure approach activities as women tended to be less vocal about pleasure and sex than men. However, pleasure implementers reported that pleasure approach activities could be an opportunity for gender stereotypes, misogynistic constructs of pleasure, and heteronormative sexual “scripts” to be unpacked, discussed, and challenged.Citation19

This analysis revealed mechanisms by which pleasure may open portals for better outcomes and overcome barriers. A pleasure approach may break down larger concepts, such as sex, into manageable parts such as desires, touches, and sensations. This provides a more granular perspective. This granularity could allow people to approach sex and sexuality more comfortably because shame and fear are associated with the larger concept of “sex” and not the smaller building blocks that make up sex as an experience. Similarly, when approaching gender and sexuality in terms of touch, sensation and pleasure, big categories such as men and women, straight, gay or queer become more accessible. This is a way of talking about what, and who brings pleasure to whom, rather than highlighting sexual identities or risks that may be stigmatised. Additionally, a pleasure approach is reported as fun and enjoyable to engage with, encouraging full and continued engagement with pleasure and SRH and bonding between groups.

How to do it: pleasure implementation recommendations

The best practices that emerged from the experiences of current pleasure implementers offer pragmatic guidance for implementing pleasure. This guidance suggests:

Approach groups and individuals with an open mind and without assumptions with regard to their prior experiences of pleasure or current reaction to the topic.

Allow participants to guide how language is used and how a pleasure approach should be introduced. A pleasure approach should be responsive and tailored.

Invest in facilitators. Training should be comprehensive and acknowledge facilitator anxiety or shame around pleasure. Support should be continuous.

Funders should centre and legitimise pleasure work in their content and application process.

Funders and technical support organisations should encourage pleasure implementers to document, evaluate and publish their pleasure work to expand the evidence base on how to apply a pleasure approach.

Limitations

The limits of this study are, first, that data were collected from a small sample of initial pleasure implementers. Second, this evaluation analysed data collected as part of routine grant monitoring, and such data are limited as potentially biased. Some of this bias was mitigated by collection of original data by an external researcher to supplement existing data, and analysis of all data by an external researcher. Lastly, this study cannot comment on the efficacy of pleasure-based SRH to improve outcomes, as this was outside the scope of the study. However, as interventions that employ a pleasure approach continue to be implemented, with guidance from pragmatic guides such as the best practices reported here, the efficacy of these interventions should be measured.

Conclusion

This paper highlights ways of understanding the possibilities and mechanisms of a pleasure approach, challenges in applying a pleasure approach, and a series of pragmatic best practices. The experiences of pleasure implementers show that implementing a pleasure approach is possible in a wide range of contexts and across a diversity of groups and communities. Groups that are often left out of discussions around pleasure, as those external to the group assume they will reject pleasure, were included, accepted, and enjoyed a pleasure approach within this project. The best practices developed here offer a range of grounded and practically driven recommendations, drawn from pleasure implementers’ experiences, that others can lean on when integrating a pleasure approach into their work. As a result of the success of this project AmplifyChange have endorsed the Pleasure Principles to continue and amplify pleasure work with their grantees going forward.

CRediT authorship statement

AmplifyChange and The Pleasure Project led on acquiring funding for this project. Authors AP and KN led on the conceptualisation of the project. The methodology was developed by RM, including development of data collection tools. Data collection were carried out by RM. Analysis and synthesis of analysis from across datasets was carried out by RM. All authors met regularly to discuss the emerging findings of the analysis. RM and KN led on project administration and planning data collection activities. EK provided resources, such as routinely collected data and grantee impact indicators. RM wrote an original draft of the published work. Authors AP, KN and EK provided review and substantive editing in preparation of the final draft of the published work.

An independent researcher, RM, conducted this study. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Case for Her, AmplifyChange or The Pleasure Project.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank all of the pleasure implementers that contributed to this work, their insights were invaluable. We would also like to thank Francesca Barolo for her helpful comments on the draft manuscript.

Disclosure statement

KN is the Communications Manager at AmplifyChange and EK is the Learning, Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist at AmplifyChange. AmplifyChange is a fund that supports civil society organisations who advocate for improved SRHR. AmplifyChange granted funding from the Case for Her to the pleasure implementers, who are the participants in this study, and coordinated the grant process. AP is the Founder and Co-Director of the Pleasure Project. The Pleasure Project is an international education and advocacy organisation which advocates for a pleasure-positive approach to SRHR. The Pleasure Project received funding from The Case for Her to provide technical assistance to the pleasure implementers.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2306073).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zaneva M, Philpott A, Singh A, et al. What is the added value of incorporating pleasure in sexual health interventions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0261034. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261034

- World Association for Sexual Health. Declaration of sexual rights. World Association for sexual health. [cited April 2023] Available from: https://worldsexualhealth.net/resources/declaration-of-sexual-rights/.

- Gianotten L, Alley J, Diamond L. The health benefits of sexual expression. Int J Sex Health. 2021;33(4):1–16. doi:10.1080/19317611.2021.1966564

- Laan M, Klein V, Werner A, et al. In pursuit of pleasure: a biopsychosocial perspective on sexual pleasure and gender. Int J Sex Health. 2021;4:1–21. doi:10.1080/19317611.2021.1965689

- Reis J, de Oliveira L, Oliveira C, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of women’s sexual pleasure: a scoping review. Int J Sex Health. 2021;4:1–22. doi:10.1080/19317611

- Philpott A, Larsson G, Singh A, et al. How to navigate a blindspot: pleasure in sexual and reproductive health and rights programming and research. Int J Sex Health. 2021;33(4):587–601. doi:10.1080/19317611.2021.1965690

- Scott-Sheldon J, Johnson T. Eroticizing creates safer sex: a research synthesis. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(6):619–640. doi:10.1007/s10935-006-0059-3

- Dixon-Mueller R. The sexuality connection in reproductive health. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24(5):269–282. doi:10.2307/2939221

- Fine M, McClelland S. Sexuality education and desire: still missing after all these years. Harv Educ Rev. 2006;76(3):297–338. doi:10.17763/haer.76.3.w5042g23122n6703

- Allen L, Carmody M. ‘Pleasure has no passport’: re-visiting the potential of pleasure in sexuality education. Sex Educ. 2012;12(4):455–468. 6.

- Gruskin S, Yadav V, Castellanos-Usigli A, et al. Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex Reprod Health Matter. 2019;27(1):29–40. doi:10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787

- Singh A, Both R, Philpott A. ‘I tell them that sex is sweet at the right time’ – a qualitative review of ‘pleasure gaps and opportunities’ in sexuality education programmes in Ghana and Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(5):788–800. doi:10.1080/17441692.2020

- Diallo D, Moore W, Ngalame M, et al. Efficacy of a single-session HIV prevention intervention for Black women: a group randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):518–529. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9672-5

- Bauermeister A, Tingler C, Demers M, et al. Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention intervention for single young men who have sex with men seeking partners online: the myDEx project. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(11):3064–3077. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02426-7

- Johnson S. ‘It’s always fear-based’: why sexual health projects should switch the focus to pleasure. The Guardian. [cited April 2023] Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/nov/22/pleasure-sexual-health-projects-reproductive-rights.

- The Pleasure Project. The pleasure principles. the pleasure project. [cited May 2023] Available from: https://thepleasureproject.org/the-pleasure-principles/.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

- Noar S, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. J. Health Commun Internat Perspect. 2006;11(4):365–390. doi:10.1080/10810730600671862

- Simon W, Gagnon H. Sexual scripts: permanence and change. Arch Sex Behav. 1986;15:97–120. doi:10.1007/BF01542219

- Ford J, Corona Vargas E, Finotelli I, et al. Why pleasure matters: its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. Int J Sex Health. 2019;31(3):217–230. doi:10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587

- Klein V, Laan E, Brunner F, et al. Sexual pleasure matters (especially for women) – data from the German Sexuality and Health Survey (GeSiD). Sexual Res Soc Pol. 2022;19:1879–1887. doi:10.1007/s13178-022-00694-y

- Ford J, Corona Vargas E, Cruz M, et al. The World Association for sexual health’s declaration on sexual pleasure: a technical guide. Int J Sex Health. 2021;33(4):612–642. doi:10.1080/19317611.2021.2023718

Appendices

Appendix 1 – Qualitative Survey

Appendix 2 – List of pleasure impact indicators

Pleasure impact indicators were chosen and measured by grantees, dependent on their context and community needs. Grantee partners decided to work towards:

Improved social norms and beliefs around sexuality and pleasure

Increased individual awareness amongst marginalised groups of their own sexual desires and pleasure as a component of SRHR as a human right.

Increased number of individuals amongst marginalised groups reached by the programme feel empowered to claim safe, consensual and pleasurable sexual lives

Improved curricula on sexual health and sexuality inclusive of pleasure and sex-positivity

Improved quality of services/information/products due to pleasure-inclusive approaches