Abstract

The narrative, arts-based research described in this article explores the visual life story approach with a group of immigrant adults (N = 7) of various cultural origins conducted in partnership with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA). The art therapy research examines the joint contribution of life story and artistic creation to enhancing the coherence of the participants’ narrative identities and psychological well-being. The phenomenological, narrative, arts-based method includes in-depth interviews focusing on the participants’ verbal accounts of their lives, followed by 12 art therapy sessions that allowed the embodiment of their lived experience into artworks. Results identify the therapeutic factors that enhance psychological well-being and highlight the integrative function of the visual life story approach. They demonstrate the healing power of art making in the company of others, and its capacity to promote reflexivity and facilitate the exploration of existential themes of universal significance. Ultimately, museum-based art therapy contributes to a heightened sense of well-being and empowerment.

RÉSUMÉ

La recherche narrative basée sur l’art décrite dans cet article explore l’approche visuelle du récit de vie auprès d’un groupe d’adultes immigrants (N = 7) d’origines culturelles diverses. Menée en partenariat avec le Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal (MBAM), cette recherche en art-thérapie examine la contribution conjointe du récit de vie et de la création artistique La méthode phénoménologique, narrative, basée sur l’art comprend des entretiens approfondis axés sur les récits verbaux des participants à propos de leur vie, suivis de 12 séances d’art-thérapie qui ont permis d’incarner leur expérience vécue dans des oeuvres d’art. Les résultats identifient les facteurs thérapeutiques qui améliorent le bien-être psychologique et mettent en évidence la fonction intégratrice de l’approche visuelle du récit de vie. Ils démontrent le pouvoir de guérison de la création artistique en compagnie d’autrui et sa capacité à promouvoir la réflexivité et à faciliter l’exploration de thèmes existentiels d’importance universelle. En fin de compte, l’art-thérapie muséale contribue à un sentiment accru de bien-être et d’autonomisation.

Introduction

This article describes an art therapy research project with a small-scale group of seven immigrant adults of various cultural origins, hosted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The research combines narrative and arts-based methods into a visual life story approach, aimed to explore the joint contribution of storytelling and art making to enhancing narrative identity and psychological well-being. A second objective aims to achieve a better understanding of the therapeutic function of artistic process in the museum context.

First, the therapeutic potential of the combined methods of life story and arts-based research will be situated within the theoretical framework that brought out two research questions: (1) What are the therapeutic factors that have been experienced by coresearchers through the visual life story approach? and (2) How did the coresearchers experience the artistic process involved in the construction of visual life stories? The following section will focus on the joint utilization of the narrative and arts-based methods in the actual research project. Moreover, the data analysis and results sections will be centered on three categories of therapeutic factors as linked to beneficial outcomes. The discussion will address the therapeutic contribution of the visual life story approach in enhancing the immigrant adults’ sense of inner coherence and well-being. Finally, the research limitations and final recommendations will conclude the article.

Theoretical framework

In art therapy, research with migrant populations has focused primarily on the migratory experience of members of certain homogeneous cultural groups, or on the refugees’ traumatic experiences. Although the narrative approach arises naturally from the art-therapeutic process (Harpaz, Citation2016), immigrant adults’ life narratives have not yet been envisioned in their globality. The point of considering their lived experience since birth instead of focusing on the migratory narratives only, is that the latter risks to underline difference at the expense of the common aspects of a shared social world (Dioh et al., Citation2021; Lutz, Citation2011). Highlighting difficulties to the exclusion of learnings, acquired strengths, and resilience, promotes an “approach based on deficits,” which evaluates individuals according to the social standards predominating in the host country. Such an approach may strengthen the power relations that define identities from the outside (Métraux, 2018, as cited in Heller, Citation2023a). In the absence of narrative models able to reflect the migrants’ life experience from a larger perspective, their stories may remain centered on the temporary losses inherent to displacement (Lutz, Citation2011).

The experience of displacement has nonetheless the potential to promote reflexivity and initiate an intensive autobiographical inner work that may lead to the reconfiguration of self (De Fina & Tseng, Citation2017; Trifanescu, Citation2013), a process to which storytelling may contribute significantly. For Paul Ricœur, life stories are essential modes of making sense of lived experience; they are necessary for the construction of identity, since they represent the only way of answering the question “Who am I?” In Ricœur’s view, the inherent suffering that characterizes human condition calls for stories. Once told and made credible, they become sources of purification, catharsis, and transformation. By telling how our life changed, we also tell how we got through it. Each time we recount our life story, we are brought to reconsider it from a new angle and refine it. Storytelling sets our imagination in motion and increases the poetic charge of our narratives, imbuing them with creativity (Ricœur 1983–1985, as cited by de Ryeckel & Delvigne, 2010).

Life stories’ main function is to facilitate the integration of the two poles of human existence into a coherent narrative identity (Gregg, Citation2006; McAdams, Citation1993, Citation2019). They allow self-affirmation, integration, and continuity, while in the meantime acknowledging ambiguity, paradoxes, and complexity. Their capacity to integrate opposites such as continuity and discontinuity resonates with the migratory experience, which eludes linearity, thus mirroring in many ways our contemporary world characterized by ruptures and fragmented realities (De Fina & Tseng, Citation2017; Trifanescu, Citation2013). The life story methodology allows researchers to integrate into the same narrative fabric both the difficulties and the positive outcomes resulting from the integration process (Dioh et al., Citation2021). Integrating negative and positive events into the same narrative creates a “springboard effect” that projects the individual toward new possibilities (Pals, Citation2006, as cited in Heller, Citation2007), and promotes resilience and agency (Cyrulnik, Citation2002; McAdams, Citation1993).

To truly fulfill its therapeutic potential, storytelling requires a friend, a therapist, or a group striving to penetrate the storyteller’s cultural world and requires their active listening. Personal narratives are thus coconstructed through interactional dynamics (De Fina & Tseng, Citation2017; Ricœur, 1983–1985, as cited by de Ryckel & Delvigne, Citation2010), hence the importance of people’s participation to interviews and group sessions that utilize this methodology.

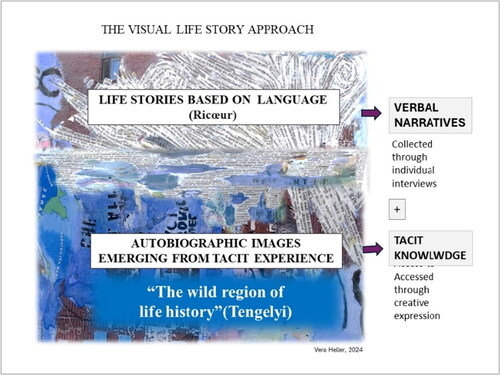

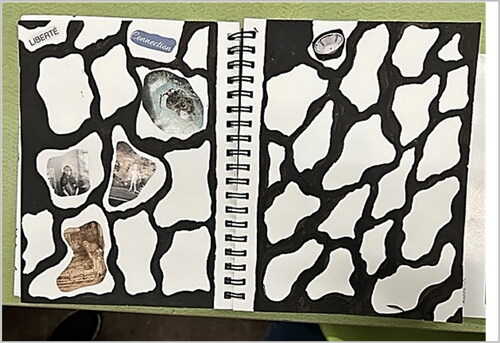

Life stories are constantly changing, depending on who is listening, or on the intervention of imaginative processes (Ricœur, 2003, as cited in Chambon, Citation2018) that are not always based on words. If for Ricœur (n.d., as cited in Tengelyi, Citation2005) the main source of life stories is language, for Tengelyi (Citation2005, as cited in Heller, Citation2023c), they have another, deeper place of origin, which he describes as wild psychic territory, a no man’s land inhabited by vague, chaotic traces of experience that have not yet been subject of an explicit account. These represent a tacit dimension of lived experience that cannot be reached through language but may be accessed through various forms of artistic expression. The unexpected surge of tacit fragments of experience into consciousness according to an autonomous process brings the individuals to reconfigure the meaning of their story. “Suddenly, we have the impression of being led by hidden forces in a determined direction […], even in the midst of events that occur almost entirely without our contribution” (Tengelyi, Citation2005, p. 28) (free translation). Although Ricœur (n.d., as cited in Tengelyi, Citation2005) envisions life as “a web of stories told through words,” he seems aware of the existence of a “hidden and uncontrollable process [that] gives birth to a new meaning” under the impact of the unexpected emergence of “an image, a face, a figure” (p. 23) (free translation). Tengelyi’s “life story’s wild region” shelters the tacit dimension of human experience that can only be accessed through art. On its part, this art therapy research project allowed the integration of both life story’s upper region – based on words – and its deeper, untamed territory. Art making and group interactions facilitated the emergence of yet unspoken fragments of experience (see ).

According to several authors, the artistic process is endowed with the capacity to incorporate scattered fragments of experience and inner polarities into a larger whole. In this regard, art’s integrative function is akin to that of life story. Integrating shapes and colors into a coherent artistic composition on a canvas triggers in the artist’s psyche a comparable process that leads toward an enhanced inner coherence (Dewey, Citation2005; Ehrenzweig, Citation1982; Nachmanovitch, 2019, as cited in Heller, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). Due to the integrative function of both art making and life story, a combination of the two methods into a single approach has the potential to contribute to the construction of migrants’ hybrid identity. The integration process that characterizes it consists in merging two part-cultures – here and there – into a “third space” that contains both (Bhabha 1996, as cited in Heller, Citation2023b).

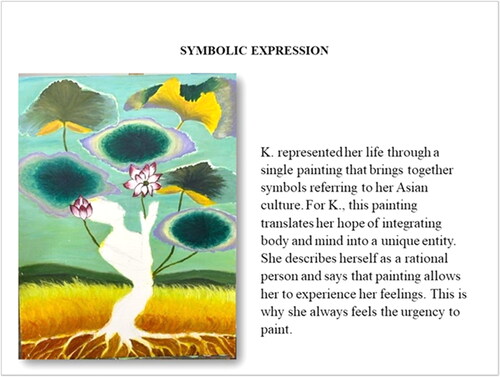

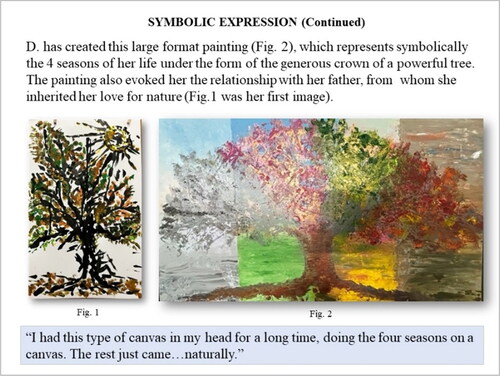

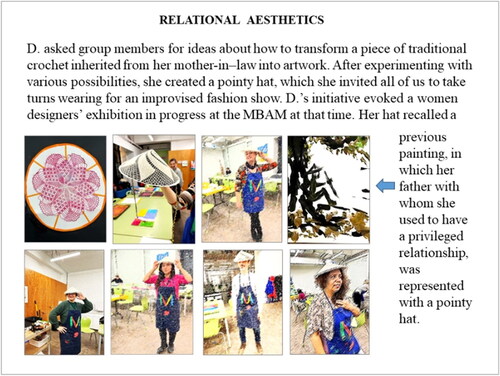

In addition to visual life story’s integrative function described above, the process experienced during the art therapy workshops benefited from the emergence of five other factors of change. Identified for the first time by Gabel and Robb (Citation2017, as cited in Holtum, Citation2020) in relation to clinical group art therapy, these have been described by the authors as symbolic expression (of thoughts and feelings), relational esthetics (the triangular relationship among artworks, participants, and group leaders), embodiment (of personal experience into artworks, as a result of the emotional connection with the exhibit), pleasure and play (leading to relaxation and mastery), and ritual (safeness of the studio-space and consistency of the therapeutic frame). These factors of change offer a substantial contribution to identifying and understanding the beneficial effects of group-based museum art therapy (Holtum, Citation2020).

Viewed as an avant-garde institution for its innovative practices (Wei & Zhong, Citation2022), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts hosted this project and ensured the presence of a cultural mediator, Farzaneh Rezaei, who is also a fine artist. A large body of research demonstrates that the participants’ emotional connections with exhibits and artworks in museums and galleries facilitate associations with their own experiences and increase their capacity for self-expression. Museum-based art therapy promotes a sense of belonging, social connection, interaction, and personal validation, thus improving the participants’ well-being (Coles, Citation2020; Holtum, Citation2020; Legari et al., Citation2020; Zhvitiashvili, Citation2020), highlighting Salom’s (2011, as cited in Holtum, Citation2020) idea of the museum as therapist.

A third series of elements that may play an important role in group art therapy are Yalom’s (2005; as cited in Moon, Citation2016) “existential factors,” namely freedom, aloneness, guilt, personal responsibility, and the inevitability of suffering and death, which represent universal dimensions of human experience. Moon (Citation2016) posits that these ultimate concerns of existence appear time and again in the art therapy sessions. Becoming aware of them, exploring, and confronting them through art making and group interactions provides great therapeutic benefits that lead to a life lived in mindfulness. Surprisingly, after having analyzed 119 sources in art therapy, Gabel and Robb (Citation2017) note that while still based on Yalom and Leszcz’s (2005) Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, most of contemporary American textbooks on group art therapy removed from their content Yalom’s “existential factors” mentioned in the original work. The only exception is Moon (2010, as cited in Gabel & Robb, Citation2017). For Moon (Citation2016), they occupy a central place along with art making. As mentioned by Yalom (2005, as cited in Moon, Citation2016), coming to terms with the existential factors is a vital task of human development and the basic condition for genuine human connections in group therapeutic contexts.

Research questions

The following research questions emerged from the literature review:

What are the therapeutic factors that have been experienced by coresearchers through the visual life story approach?

How did the coresearchers experience the artistic process involved in the construction of visual life stories?

Methods

Stories offer “especially translucent windows into cultural and social meanings” and may include in-depth interviews and life story narratives (Patton, 2002, as cited in Kapitan, Citation2010, p. 153). The narrative analysis method is a variant of phenomenological research aiming to understand and make explicit the coresearchers’ lived experience, as perceived from their own perspective (Ntebutse & Croyere, Citation2016). Referring to the evocative, authentic dimension of narratives, Merleau-Ponty (as cited in Kapitan Citation2010) compared this phenomenological method to a poetic activity. Some forms of narrative research, such as arts-based and visual-based inquiry, use photos, collages, or paintings as an integral part of the research process (Kim, 2016, as cited in Sultan, Citation2019). Like the narrative method, in-depth research in art therapy aims to understand human experience. Consequently, the two forms of inquiry can be combined on a phenomenological ground, art making itself being a form of direct experience that can be envisioned phenomenologically (Kapitan, Citation2010).

This research project combined narrative inquiry and art-based research into a single approach, as embedded into a series of in-depth individual interviews and 12 art therapy sessions hosted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA). A small-scale group of seven migrant adults of various cultural origins participated in the project. Originating from Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia, they were recruited via community organizations and social networks. The average age within the group was about 35. Although the sessions took place in French, some comments related to their experience have been translated in English to illustrate the art therapeutic process. As in narrative inquiry, research participants are considered coresearchers (Kapitan, Citation2010, p. 175; Ntebutse & Croyere, Citation2016; Sultan, Citation2019); this section will refer to them as such. Following the ethical approval of the University of Québec in Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), the coresearchers signed consent forms with detailed explanations concerning the use of the data and mentioning that they were free to withdraw at any time. A community agency offering psychological services to immigrant adults was ready to welcome them in case the art therapy processes awakened traumatic or painful memories.

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

The project started with in-depth interviews conducted by the researcher during the fall of 2022. They were aimed to collect the coresearchers’ verbal narratives, which were transcribed professionally and sent through email to their authors, who were free to revise, complete, or reformulate them. Meant to set in motion the coresearchers’ memory and imagination, the interviews were followed during the winter of 2023 by 12 art therapy sessions hosted by the MMFA. The workshops allowed group members to embody their life experiences into images. They were led in complementarity by the art therapist-researcher, who insured an adequate therapeutic framework, and the museum’s cultural mediator, who facilitated the coresearchers’ contact with the museum’s digital collection on the one hand, and their own artistic processes on the other. The common thread of art therapy sessions was the artistic creation of personal life stories, of which each coresearcher had an overall idea following the interviews. Therefore, no thematic structure was provided for the weekly sessions, according to the idea that significant material would emerge spontaneously during art making and group interactions (Yalom, 2005, as cited in Moon, Citation2016; Tengelyi, Citation2005). Each three hour-session provided for 20 minutes of discussion at the beginning that allowed the coresearchers to check-in, and 30 to 40 minutes at the end, dedicated to sharing about the images they produced. As posited by De Fina and Tseng (Citation2017), the group interactions contributed to the coconstruction of group members’ personal narratives. Letting go of pre-established goals facilitated the coresearchers’ access to the tacit dimension of experience and allowed the autonomous dimension of the artistic process to fulfill its integrative, structuring function (McNiff, Citation2013; Tengelyi, Citation2005).

Data collection

The data collection includes the interviews and group discussions transcripts, and 123 images created during the workshops. Having had a particular impact on some of the coresearchers’ processes, a few artworks from the museum’s collection are equally considered part of the data.

Analysis

Carried out through cross-referencing visual and verbal data, the analysis aimed at understanding the coresearchers’ life experience, and transcribing it into explicit knowledge that privileges the participants’ perspective (Ntebutse & Croyere, Citation2016). Given the magnitude of the data collection, this article will focus on the group processes that took place in the museum context and on their impact on the individual life stories. The study of experience will refer to descriptions of thoughts, feelings, and images (Kapitan, Citation2010), as linked to the therapeutic factors of change previously identified through the literature review.

Results

As indicated in , the coresearchers’ experience has been examined in relation to three different series of therapeutic factors: (1) Gabel and Robb’s (Citation2017) factors of change in group art therapy, (2) therapeutic factors emerging from the artistic process, and (3) Yalom’s (2005) existential factors in group interactions. Each series of therapeutic factors will be associated to concrete examples of beneficial outcomes, as experienced by the coresearchers.

Table 1. Therapeutic factors in museum art therapy.

To facilitate comprehension, the therapeutic factors will be presented separately in the results section, although they were organically interrelated in the art therapy process.

1. Illustrated examples of Gabel and Robb’s (Citation2017) factors of change in group art therapy are presented in to below.

2. Therapeutic factors emerging from the artistic process

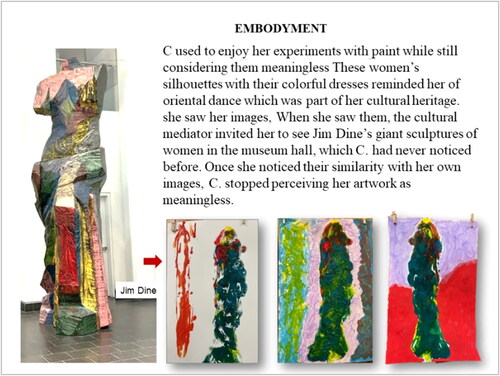

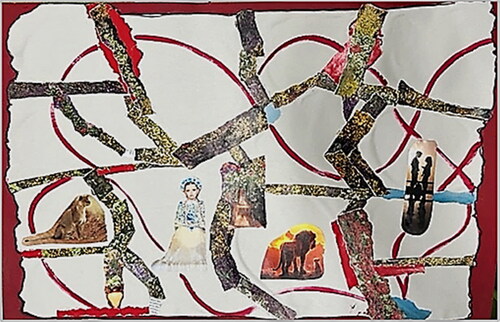

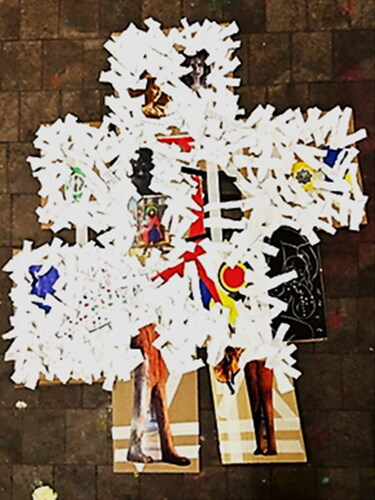

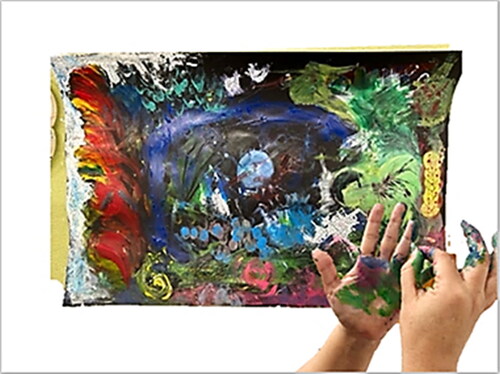

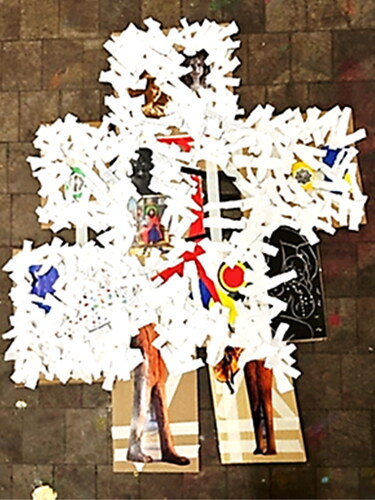

The coresearchers’ experience demonstrates that the joint use of life story and arts-based methodologies contributed to bringing together inner polarities and fragments into a more cohesive sense of self. For example, B. enjoyed tearing up pieces of paper and gluing them on a cardboard. She commented that these were “like the pieces of myself” (see and ). Her artworks recall Ehrenzweig’s (1967; as cited in Heller, Citation2023a, Citation2023b) suggestion that artistic and psychic processes take place in parallel. Ehrenzweig maintains that art has a hidden capacity to order and integrate scattered pieces of experience into a new whole. This structuring process can be perceived through both the coherence of the composition, and the artist’s sense of enhanced psychic integration.

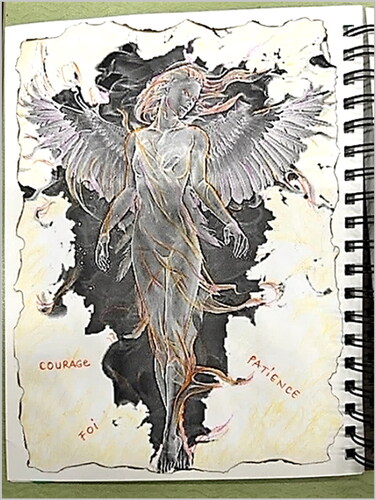

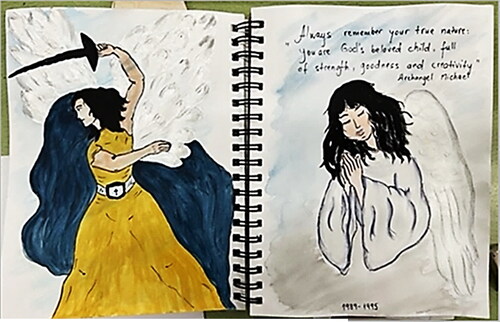

For her part, R. compared her sense of identity in the beginning of the art therapy sessions, to “a broken mirror.” She noted that the creative process helped her to assemble its pieces and mend it (see ) and felt that art therapy allowed her to integrate the two polarities of her life, which she defined as shadow and light. R. described her inner experience through the metaphor of Phoenix bird’s rebirth from its own ashes (see ). “I came out of the shadows, where my father placed me for decades. Then came all the flowering, my flowering, then the opening, then the light”. Her testimony corroborates Pals’ (Citation2006) observation that incorporating the positive and the negative experience into the same narrative fabric has a springboard effect that projects the individual toward psychological transformation. R. described the qualities that allowed her inner transformation as courage, patience, and faith.

Two other qualities whose development has been encouraged during the workshops were spontaneity and the ability to let go of preconceived objectives. They facilitated the unexpected emergence of surprising images from the tacit depths of lived experience, according to a “hidden and uncontrollable process” (Ricœur, n.d., as cited in Tengelyi, Citation2005, p. 23), which traced the common thread of each story, independently of the artists’ will, giving birth to new meaning.

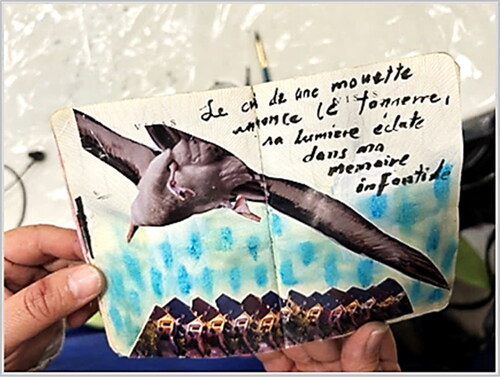

A. recounts that she used to paint, but with time, her creativity got blocked for years by her suffering related to an unresolved trauma. After a few art therapy sessions, she experienced a sense of letting go that was accompanied by the pleasure of direct contact with the medium (see ). With reference to the early events that marked her life, she wrote: “The cry of a seagull announces thunder, the light bursts in my childhood memory.”

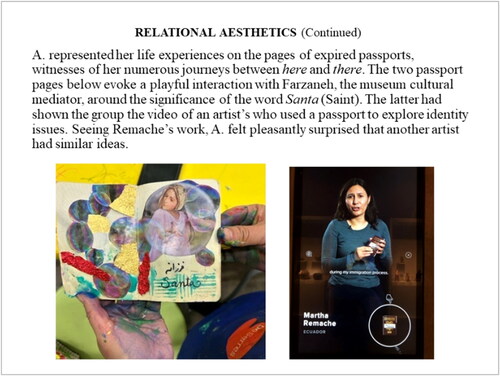

A. reconstructed significant episodes of her life on the pages of expired passports (see ). Her work reminds of the artistic process’ capacity to awaken memory, poetize experience, and fictionalize life’s raw material through image making. Her capacity to gradually release control and enjoy the process has been facilitated by the museum art therapy context and her playful interactions with Farzaneh Rezaei, the museum cultural mediator.

As new images sprang from their memories, the coresearchers experienced a sense of awe and transformation, which allowed them to imbue their stories with creativity and reconfigure their meanings. The two following comments demonstrate that letting go of rational objectives, and of the need to reproduce the life story already recounted during the interviews allowed for discovery and transformation.

B. noticed that the few lines and forms she drew randomly on the paper during the first session brought about unexpected images that she immediately found meaningful. “It was not planned; the images and the whole collage just came out before my eyes,” she commented. Her observation highlights the autonomy of the artistic process, which consists in a release of hidden, subterranean forces that lead the artist in an unplanned but specific direction.

N.’s observations go in the same direction:

I didn’t know I was working on this, it just popped up […]. This was perhaps the deepest, the most important thing at that moment, […] but if we do it spontaneously, there are symbols, things that come out, that speak only to us, because it’s up to us to then go and work on them. So, it’s easier after that […] to expect to be amazed by what happened.

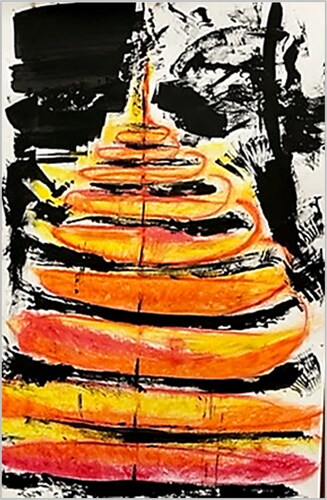

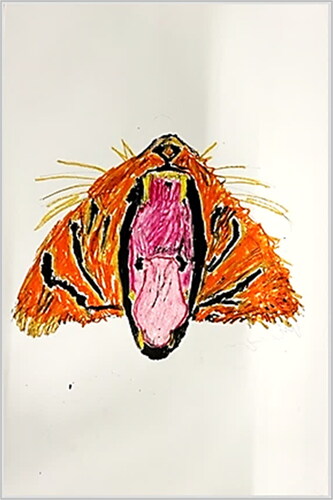

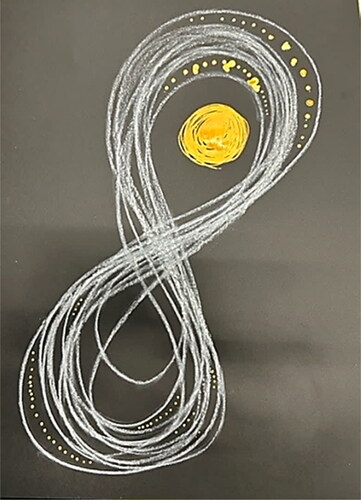

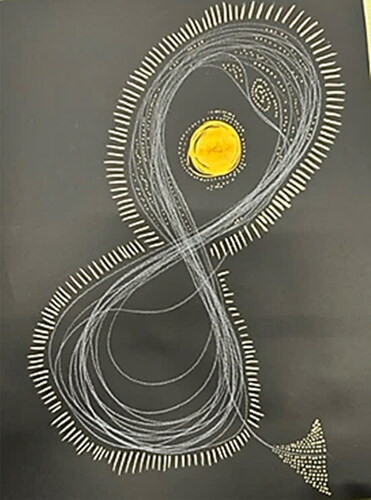

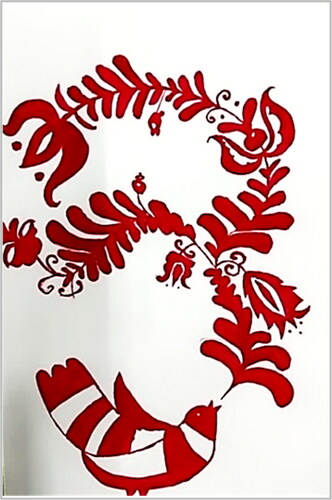

N. compared his life story’s unfolding to a fragile spiral whose wider and wider circles passed by the same types of experiences, but of increased complexity (see ). Allowing his creative process to guide him resulted in a series of images of which he was surprised. Most of his images are related to the unexpected emergence of childhood forgotten memories: a tiger’s open mouth in a zoo (see ), and his loss of innocence when his money got stolen in a summer camp (see ).

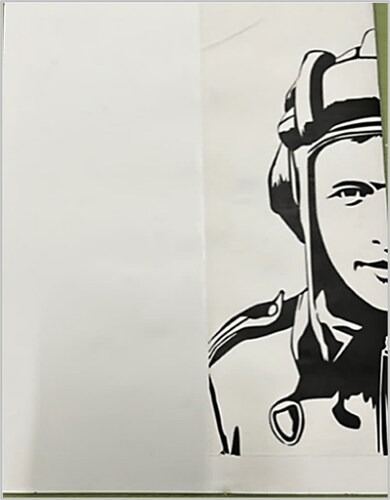

Later, the memory of one of his close relatives’ suicide came up as unexpectedly as the previous ones (see ), followed, during the subsequent sessions, by memories related to his parents. A negative word spoken by his father in relation to his future remained engraved both in N.’s memory and between the colorful lines that surround his portrait (see and ).

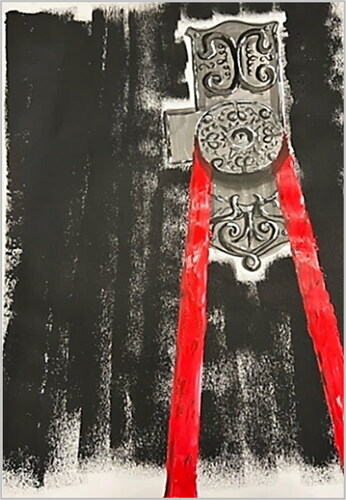

In contrast to the clear, colorful background of his father’s portrait, his mother’s protective, stable, and luminous presence is evoked on a black background through the symbol of infinity. As a child, “I was a kind of electron revolving around an atom,” shared N. (see , , and ).

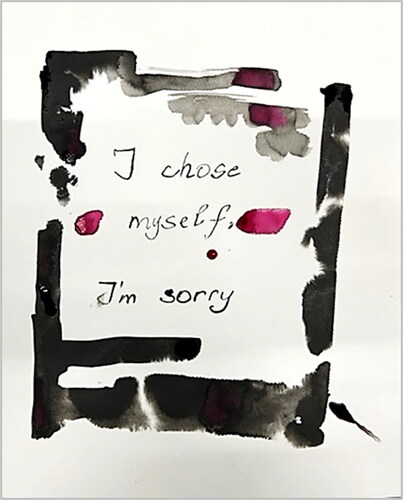

Other images emerged, completing N.’s life story. They included his self-portrait as a joyful child made from a photograph found by chance in a family album (see ), and a symbolic representation of his cultural background originating from a TV show he used to watch in his childhood (see ). A song titled I choose myself, I’m sorry mirrors the mixed feelings of guilt and jubilation experienced by N. when he left his parental home as a young adult (see ).

During the revision of his visual life story, N. underlined the therapeutic benefits he experienced:

So, was it the fact that I took a distance that made me feel more, I don’t know, more in a good mood, the fact that I’ve got through things, experienced things, whether they were, tragic, or whatever. And at the same time, I know that I am much more realistic, in the sense that I tell myself: anything can happen at any time.

3. Yalom’s (2005) existential factors and group interactions

According to Moon (Citation2016), Yalom’s “existential factors” emerge time and again in art therapy group interactions. Their emergence is facilitated by the existential dimension of art, which allows transforming difficulties into a source of creative work. Art making in a group context generates reflexivity and a sense of belonging, both of which are favorable to the exploration of the human ultimate concerns, namely freedom, death, solitude, and the meaning of life (Moon, Citation2016). In the framework of this research project, the group discussions led to the observation that most of the coresearchers had similar personal quests, a common need for in-depth understanding of their lives, and the desire to share with the others their existential preoccupations.

R. associated freedom with being given the opportunity to create: “Here I experienced a profound freedom. Nothing planned, nothing done in advance. I was looking for myself, and I found a lot of answers to my questions.” For his part, N. envisioned freedom from the angle of personal choice and personal responsibility for one’s life, as embodied into a song titled, I choose myself, I’m sorry, which he used to listen to in his youth. The song reminds him of his departure from his parents’ home when he was 20 (see ).

I had some guilt to say I’m sorry but was going to choose myself first. This is the moment when I left my country […]. Then I felt much more at home. Without feeling guilty […], I also realized that yes, sometimes in life you must be selfish too. And despite of it, you can still be a good person.

The ultimate preoccupation with the inevitability of suffering and death, mourning and the finitude of life was a common theme that emerged from the shared images and group discussions. Talking about it generated deep reflexivity within the group and became a source of creative work for some coresearchers.

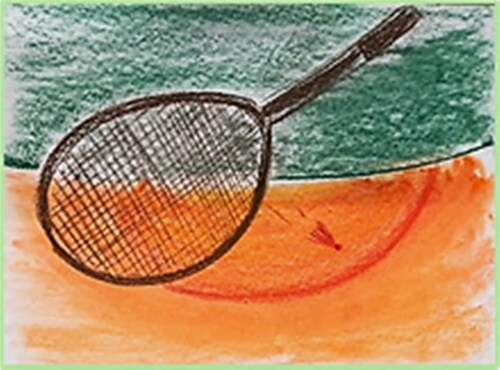

Following the unexpected surge of a memory about a close relative’s suicide, N. drew a red rope hanging on the doorknob (see ), only to realize that the image did not reflect the reality. “Over time, our memories become corrupted. The rope was not hanging on the doorknob, it was in the corner of the room.” N’s story influenced B.’s, who remembered the first moment when she became aware of death (see ).

Figure 27. B.’s sudden awareness of the finitude of life as she was playing badminton with her friends.

N. recounted: “It was when I was playing badminton with some of my friends. It was in the evening, the sun had not yet set, when I suddenly realized that I was mortal. This is to say, life is not eternal, so it’s time to be myself.” She concluded that ultimately, her awareness of death at an early age gave meaning to her life: “Yes, I still have some memories about the psychological, stressful energy that I experienced. Perhaps it endowed me with sensitivity.”

During the following art therapy sessions, B. noted that her creative process was contributing to her increased feeling that her life has meaning.

Coming here, I thought I’m like…how can I put this? Like the cycle of my life was somewhat broken. And that now I’m starting to grow roots, I could say, it’s like I was a broken tree. […] Yes, it’s like I’m building myself.

In her collage, she represented her growing roots by gluing on her collage made of reassembled pieces the solid, wooden legs of one of Jim Dine’s sculptures from the MMFA’s collection, of which she found a photograph in one of the museum’s illustrated magazines (see ). Made of crumpled paper, a nest occupies the center of her second collage. The nest is held by a hand that, according to N., symbolizes her freedom to create (see ). “The nest is where life begins. It is our right to security. It’s a safe place, it’s a hiding place ().”

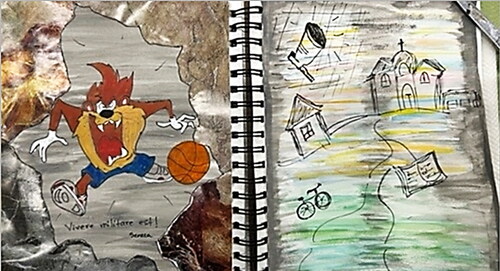

For her part, R. associated the meaning of life to spirituality viewed as a source of resilience that helped her to accept her solitude and overcome difficult moments. “Yes, [my spirituality] helped me feel that I am not alone, that ultimately, all of these [life tests] are lessons that will make me stronger, more resourceful. It [my spirituality] gave me the strength to get through it” (see ). Structured through several chapters, her life story features the “Tasmanian devil,” the resourceful character from a comic book that inspired her during the painful times of her adolescence (see ).

Figure 31. The Tasmanian devil, a representation of resourcefulness (left) and other significant symbols of R.’s life story (right).

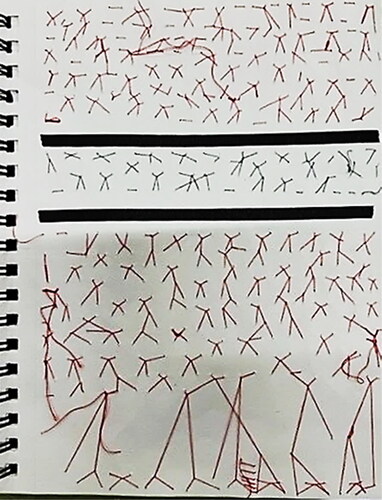

B.’s preoccupation with solitude took the form of the incommunicability she experienced in relation to her father, to whom she addressed a indecipherable hand-sewn letter (see ).

Discussion

The results presented in this article aimed to answer the following two research questions: (1) What are the therapeutic factors that have been experienced by coresearchers through the visual life story approach? and (2) How did the coresearchers experience the artistic process involved in the construction of visual life stories? The findings demonstrate the beneficial outcomes of various therapeutic factors that emerged from the visual life story approach. As mentioned by Kaiser and Deaver (Citation2013), Kapitan (Citation2010), and Robb (2016, as cited in Gabel and Robb, Citation2017), given today’s increasing efforts to prove the efficacy of art therapy, researching the therapeutic factors emerging from clinical practice has become a priority. In this qualitative research project, the mechanisms of change are the beneficial outcomes, as embodied into the visual life story approach itself. During the last few decades, the growing scientific literature in the domain of narrative inquiry assumed that talking about their past in a coherent way is beneficial for people’s psychological adjustment. The ability to tell coherent autobiographical narratives reflects their psychological health and is correlated to a higher sense of purpose and meaning, as one of the factors that define personal well-being (Waters & Fivush, Citation2014).

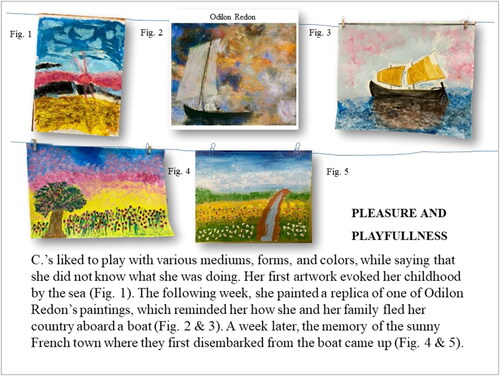

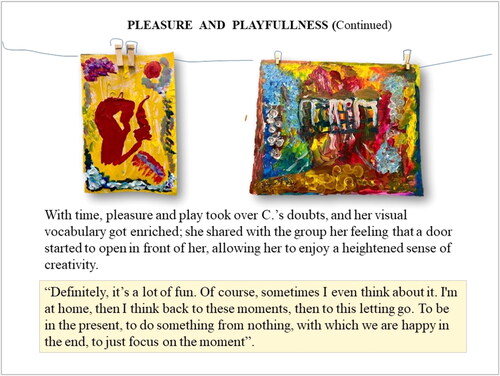

The integrative function of the joint approach of art making and storytelling has been mentioned in the results section, as one of the most beneficial mechanisms of change. As observed by C., visual life story offers the possibility to balance the often-constraining rules and goals that govern everyday life with spontaneity and free experimentation:

My daily life where I had to plan everything, to always be correct, to keep my mouth shut, to respect boundaries, to stay on the right line, and then, despite that, everything falls back on you. Here it was like, we experiment, we let go, then we’ll see how it ends. And it ended well.

The life story approach promotes reflexivity and facilitates the exploration of deep existential themes of universal concern. As mentioned in the previous section, these occurred spontaneously during the art making and group discussions and proved to be an integral part of the process. Coming to terms with the existential life concerns is a vital task of human development, and a basic condition for authentic group connections (Yalom, 2005, as cited in Moon, Citation2016).

On their part, the five therapeutic factors identified by Gabel and Robb (Citation2017) played an important role in this museum-based art therapy project. They allowed the development of triangular interactions between coresearchers, artworks, and facilitators. They resulted in an enhanced capacity for self-expression. They allowed for rich symbolic synthesis of personal experience, while promoting empathy, authenticity, openness, and a sense of belonging.

The group interactions in the museum space contributed to the coconstruction of the members’ life stories, of which some artworks from the museum collection became an integral part. As testified by coresearchers, the feeling of safeness and belonging experienced during the sessions allowed for spontaneity, experimentation, authenticity, and pleasure. Sharing their reflections with other group members of different cultural origins – but with similar life experiences – highlighted both the universal and the unique dimensions of life story.

The research described in this article is in continuity with the researcher’s previous research projects that focused on migratory experience (Heller, Citation2007, Citation2023a) with the difference that the actual project approaches life stories in a global manner. Of course, the attempt to grasp an individual’s entire life through a single interview and 12 art therapy sessions would be illusory. Nonetheless, storytelling allows a person to be understood in their total dimension (Ricoeur, 2003, as cited in Chambon, Citation2018). Life stories contribute to a coherent sense of self, while also making space for plurality and fragmentation thus mirroring the characteristics of a contemporary world in perpetual movement. As De Fina and Tseng (Citation2017) point out, life stories represent engaging, natural, and spontaneous ways of reflecting on experience, while creating rapport. In this regard, coresearcher R.’s comments corroborate this view:

A kind of door had opened for me, because before participating in this workshop, I was searching for myself. I was looking for how to say, how to hold on to something, how to overcome all the fire that I had inside […] I felt super included, super at my place, with people who share the same mindset.

The integrative function of visual life story reduces the gap between here and there, and mends psychic fragmentation. Integrating negative and positive life experiences into a unique story brings into balance the individual’s life and changes one’s perception about remembered events. Reflexivity and the capacity to examine one’s life with a certain distance are the source of narrative identity. Life stories are not only about past events, but they also demonstrate the practical wisdom put into action by the storyteller (Ntebutse & Croyere, Citation2016). As sources of transformation, they contribute to our psychological well-being, a quality that demonstrates their therapeutic value. By placing the individual at the center of their own lived experience, the approach of visual life story promotes empowerment. It allows the creation of artworks that individuals do for themselves in good company, in search of their own mode of expression. “All sorrows are bearable if we tell a story about them” (Cyrulnik, Citation2002).

Limitations and recommendations

This paper describes a research project with a small-scale group of participants. The small scale, which is typical for some forms of phenomenological research such as heuristic inquiry (Kapitan, Citation2010), limits the generalizability of findings. As phenomenological inquiry is based on subjective, direct lived experience, its validity is concerned with the quality of meaning provided by the results. The final meaning obtained is meant to convey what is psychologically essential about the participants’ experience, which does not lend itself to replication (Kapitan, Citation2010). As far as the present project is concerned, the beneficial outcomes highlighted by the results could be validated by carrying out several qualitative research projects of museum art therapy – or in other clinical contexts – with various groups of immigrant adults. The recommendations of De Fina and Tseng (Citation2017) to the effect that “scholars will also need to engage more fully with hybrid and transnational identities as the world in which migrants move becomes more and more interconnected” (p. 392) may also be applicable to the field of art therapy, through qualitative research on the visual life story approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Coles, A. (2020). What do museums mean? Public perceptions of the purposes of museums andimplications for their use in art therapy. In A. Coles and H. Jury (Eds.), Art therapy in museums and galleries. Reframing practice. Jessica Kingsley.

- Cyrulnik, B. (2002). Un merveilleux malheur. Odile Jacob.

- Chambon, N. (2018). Raconter son histoire comme personne: les migrants et leurs récits. Le sujet dans la Cité. Revue internationale de recherche biographique, 9(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.3917/lsdlc.009.0063

- De Fina, A., & Tseng, A. (2017). Narrative in the study of migrants. In S. Canagarajah (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of migration and language (1st ed., pp. 381–396). Routledge. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316088359_Narrative_in_the_study_of_migrants

- de Ryckel, C., & Delvigne, F. (2010). La construction de l‘identité par le récit. Psychothérapies, 30(4), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.3917/psys.104.0229

- Dewey, J. (2005). Art as experience. Tarcher Perigee. (Original work published 1934).

- Dioh, M.-L., Gagnon, R., & Racine, M. (2021). Le récit de vie comme voie d’accès àl’expérience vécue par des personnes immigrantes en processus d’intégration dans la région des Laurentides. Récits de vie et savoirs: Enjeux des enquêtes narratives, 40(2), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.7202/1084068ar

- Ehrenzweig, A. (1982). L’ordre caché de l’art. Essai sur la psychologie de l’imagination artistique (F. Lacoue-Labarthe et C. Nancy, Trans.). Gallimard. (Original work published 1967 under the title The hidden order of art).

- Gabel, A., & Robb, M. (2017). (Re)considering psychological constructs: A thematic synthesisdefining five therapeutic factors in group art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.05.005

- Gregg, G. S. (2006). The raw and the bland: A structural model of narrative identity. In D. P. McAdams, R. Josselson, & A. Lieblich (Eds.), Identity and story: Creating self in narrative (pp. 63–88). American Psychological Association.

- Harpaz, R (2016). Storytelling as visual narratives representations in art therapy. In M. Heitkemper-Yates & A. Penjak (Eds.), The practice of narrative: Storytelling in a global context (pp. 135–147). Inter-Disciplinary Press.

- Heller, V. (2007). Exile, identity, and artistic creation: An arts-based phenomenological study with immigrant women [Doctoral dissertation]. Lesley University, EU.

- Heller, V. (2023a). Le parcours du Héros: Une intervention de groupe auprès desmigrants existentiels [The Hero’s journey: A group intervention with existential migrants]. In L. Pelletier & J. Lambert (Eds.). L’art-thérapie auprès des groupes: Réflexions théoriques et développements cliniques. PUQ.

- Heller, V. (2023b). Visual auto ethnography: A transformative practice ofremembering. In M. López Fdez Cao, R. Hougham, & S. Scoble (Eds.), Memory: Shaping connections in the arts therapies. Routledge. [Manuscript submitted for publication].

- Heller, V. (2023c). Qu’y a-t-il derrière le masque de la morale prolétarienne qui meréduit au silence? (What is behind the mask of proletarian morality that silences me?) International Journal Sociocultural Community Development and Practices. UQAM, 25, 542. https://edition.uqam.ca/atps/article/view/1542

- Holtum, S. (2020). Art therapy in museums and galleries: Evidence and research. In A. Coles & H. Jury (Eds.), Art therapy in museums and galleries. Reframingpractice. Jessica Kingsley.

- Kaiser, D., & Deaver, S. P. (2013). Establishing a research agenda for art therapy: A Delphi STUDY. Art Therapy, 30(3), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2013.819281

- Kapitan, L. (2010). An introduction to art therapy research. Routledge.

- Legari, S., Lajeunesse, M., & Giroux, L. (2020). The caring museum/Le musée quisoigne: Art therapy at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. In A. Coles & H. Jury (Eds.), Art therapy in museums and galleries. Reframing practice. Jessica Kingsley.

- Lutz, H. (2011). Lost in translation? The role of language in migrants’ biographies: Whatcan micro-sociologists learn from Eva Hoffman? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 18(4), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506811415195

- McAdams, D. (1993). The stories we live by: Personal myths and the making of the self (1st ed.). The Guilford Press.

- McAdams, D. P. (2019). First, we invented stories, then they changed us. The evolution of narrative identity. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 3(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.26613/esic.3.1.110

- McNiff, S. (2013). Art as research: Opportunities and challenges. Intellect.

- Moon, B. (2016). Art-based group therapy: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). Charles C. Thomas.

- Ntebutse, J. G., & Croyere, N. (2016). Intérêt et valeur du récit phénoménologique: unelogique de découverte. Recherches en soins infirmiers, 1(124), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.3917/rsi.124.0028

- Pals, J. L. (2006). Constructing the “springboard effect”: Causal connections, selmaking, and growth within the life story. In D. P. McAdams, R. Josselson, & A. Lieblich (Eds.), Identity and story: Creating self in narrative (pp. 175–200). American Psychological Association.

- Sultan, N. (2019). Heuristic inquiry. Researching human experience holistically. SAGE.

- Tengelyi, L. (2005). L’histoire d’une vie et sa région sauvage. Jerôme Million. (Originalwork published 2004).

- Trifanescu, L. (2013). « Le Je en migration » temporalités des parcours et nouvellesrhétoriques du sujet. Le sujet dans la cité, 4(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.3917/lsdlc.004.0237

- Zhvitiashvili, N. (2020). From isolation to relation: Reflections on the development of museum based art therapy in Russia. In A. Coles & H. Jury (Eds.), Art therapy in museums and galleries. Reframing practice. Jessica Kingsley.

- Waters, T. E. A., & Fivush, R. (2014). Relations between narrative coherence, identity, and psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality, 83(4), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12120

- Wei, Z., & Zhong, C. (2022). Museums and art therapy: A bibliometric analysis of the potential of museum art therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1041950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1041950