Abstract

Introduction

Career advising for medical students can be challenging for both the student and the adviser. Our objective was to design, implement, and evaluate a “flipped classroom” style advising session.

Methods

We performed a single-center cross-sectional study at an academic medical center, where a novel flipped classroom style student advising model was implemented and evaluated. In this model, students were provided a document to review and fill out prior to their one-on-one advising session.

Results

Ninety-four percent (95% CI, 88%–100%) of the medical students surveyed felt that the advising session was more effective as a result of the outline provided and completed before the session and that the pre-advising document helped them gain a better understanding of the content to be discussed at the session.

Conclusion

Utilization of the flipped classroom style advising document was an engaging advising technique that was well received by students at our institution.

Introduction

Career advising for medical students can be challenging for both the student and the adviser. In order to be effective, a career adviser must establish an advising framework, develop rapport, and educate the advisee. These components can be a challenging task to accomplish, as advisers are often responsible for providing academic advice to hundreds of students. Forward-thinking medical school programs have adopted smaller advising groups, thereby decreasing the student-to-adviser ratio.Citation1 Despite these efforts, time constraints of the adviser and advisee often remain barriers to optimized advising sessions.

Flipped classroom methodologies, which require students to preview material and prepare for didactic or small group sessions ahead of in-person meetings, have gained traction in teaching institutions and educational settings because they free up classroom time to focus on the application of the information learned prior to the meeting. They have been shown to maximize learning and create a more engaged student experience.Citation2 As a result, classroom sessions reinforce and implement the concepts learned outside of the classroom.Citation2 Numerous undergraduate and graduate programs have adopted flipped classroom techniques to redesign traditional curricula. To our knowledge, there is no existing research on flipped classroom and medical student career advising.Citation3 Our objective was to design, implement, and evaluate a “flipped classroom” style advising session, where students prepare at home prior to meeting with their advising mentor.

Methods

Study design and population

We performed a single-center cross-sectional study conducted at an academic medical center. This study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) of University of Arizona College of Medicine and determined to be a quality improvement project that required neither IRB oversight nor informed consent. At our institution, the student body is divided into four longitudinal “houses”, and each house is led by a Dean of Student Affairs who serves as the primary career adviser for the students in their house. This study was performed within one of the four houses. The study participants were 57 medical students (30 first-year students [MS1] and 27 second-year students [MS2]). Participation in the study was voluntary.

Flipped classroom advising

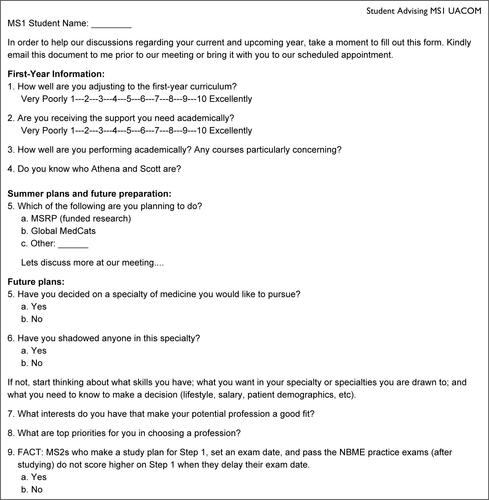

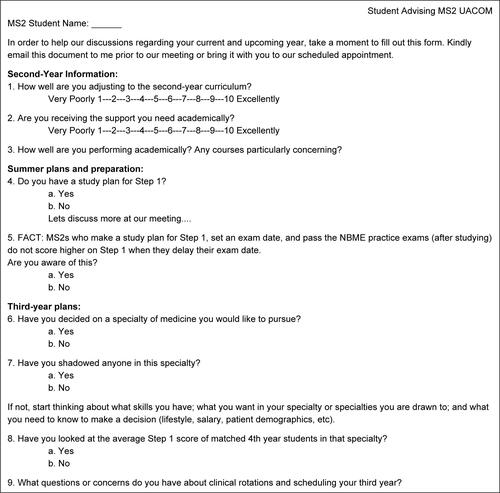

A 1-hour one-on-one student well-being and career advising session was provided to MS1 and MS2 in one of the four medical school houses. Students received a document from their adviser and were asked to read and complete this form prior to their one-on-one advising session (Figures S1 and S2). This document was developed based on the recommendations made by the American Academy of Medical Colleges (AAMC) Careers in Medicine Advising Checklist and edited for content specific to our college of medicine.

Advising document

The advising document used during these sessions addressed a wide range of topics, including students’ self-perceived performance during the academic year, students’ participation with learning specialists in the office of student development, MS1 and MS2 specific summer plans, United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 study plans, and any student concerns with the current academic progress.

Evaluation

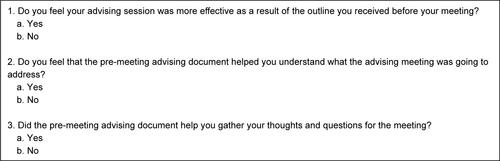

Medical students’ evaluation of the flipped classroom style advising process and session was conducted using a three-item multiple-choice questionnaire (Figure S3). The email link was sent a total of two times.

Data analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Data are presented as percentages with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

A total of 17 (30%) of the 57 students responded and completed all the required questions. Ninety-four percent (95% CI, 88%–100%) of students felt that the advising session was more effective as a result of the pre-meeting advising document received before the session. Ninety-four percent (95% CI, 88%–100%) of students felt that the pre-meeting advising document helped them understand what topics the advising session was going to address. Fifty-nine percent (95% CI, 46%–72%) of students felt that the pre-meeting advising document helped them organize and prepare for the meeting.

Discussion

Flipped classroom techniques are increasingly understood to be an important aspect of modern medical education. Investigations have demonstrated that students who participated in a “flipped classroom” approach were more likely than traditional classroom students to agree that active student engagement was encouraged by the instructor and preparation for class was necessary to be successful.Citation3 Academic and career advising serves as an effective avenue for the flipped classroom approach because it enables students to be more adept at navigating the rocky terrain of university education. When students are given a pre-advising session task, they become proactive in guiding their adviser to assist them in accomplishing their goals. At Kansas State University, SteeleCitation3 stated that the implementation of interactive exercises and modules supports the advising process by allowing advisers the ability to evaluate students’ goals, learning, and overall performance. Flipped advising leads to more positive outcomes for students by providing a structured approach for students to hone in on their pursuits, academic progress, and areas of weakness. Additionally, the flipped advising approach changes the relationship between student and adviser, and advising becomes a 24/7 model in which student and mentor work together to help the students’ academic and career goals.Citation4

The current dilemma regarding the standard academic advising paradigm is that sessions become inefficient and ineffective at meeting the students where they are at in terms of overcoming obstacles to achieving their aspirations. It is common for students to depend on their advisers to tell them about required courses to meet general education requirements, prerequisites, and possible programs to help academic goals.Citation5 LeonardCitation6 described that advising must use technology to become effective and efficient at anticipating and managing students’ unique academic portfolios. It is possible that incorporating technology such as video-recorded lectures would allow an advising session to go beyond the basic interaction of a student and adviser and help transition from “small talk” to developing a comprehensive management plan unique to the student.

In our investigation, the advising document was created as a complement to the advising handouts of the AAMC Careers in Medicine but tailored specifically to our institution. There are certain benefits obtained with creating an institution-specific advising document. Not all students, or class of students, are similar, and individual questions can be tailored to address unique concerns. For example, in a previous year, we noted a large number of students were interested in postponing their first attempt at the USMLE Step 1 examination because of a desire to improve their score. These students had successfully passed practice examinations and were doing well on test prep content scores prior to their desire to postpone. As a result of this trend, the advising document was devised to bring this issue to the attention of the student and the adviser, during subsequent years, so as to mitigate the issue preemptively.

Although we were able to successfully integrate one form of flipped class style education, there are various techniques that should be investigated further. MerlinCitation7 had described various flipped class style techniques such as incorporation of screen capture video recordings, podcast, group activity, group question and answer sessions, and many more. Furthermore, Fulton and GonzalezCitation8 had described the benefit of using flipped class education for material that is considered less interesting or typically less engaging. Future iterations of this investigation include the creation and use of existing video tutorials as primers for flipped class model academic and career advising.

The extreme stresses of medical school, along with competition and isolation, are critical factors that weigh heavily on medical students.Citation4 Owing to the rigorous demands of medical school education and the possible psychosocial disruption it may cause students, it becomes imperative that mentors and advisers ensure that each individual student’s unique needs are met. Mentoring in the medical school setting provides challenges including time constraints for both medical students and their physician mentors who are often working long hours. Establishing medical student academic and career advising using flipped classroom techniques such as the one described in this study was a logical first step in addressing this issue at our institution.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, our investigation included only preclinical students. Although the magnitude of effect was large, our sample size was small. The small sample size may be due to the voluntary nature of the study and perhaps that this request was made only one time via email. Furthermore, we did not compare advising techniques, and thus cannot draw relevant conclusions with regard to the superior advising technique. Our advising document and survey instrument were not validated prior to their use in this investigation, and as with any survey, results are vulnerable to response bias. Lastly, we only used one form of flipped classroom style technique; future studies should further investigate the utility of flipped classroom for academic and career advising.

Conclusion

Utilization of the flipped classroom style advising document was an engaging advising technique that was well received by students at our institution.

Supplementary materials

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SastreEAImprovements in medical school wellness and career counseling: a comparison of one-on-one advising to an Advisory College ProgramMed Teach2010321042943520423264

- TuckerBThe Flipped Classroom: INSTRUCTION at Home Frees Class Time for LearningEducation Next20128283 Available from: http://educationnext.org/the-flipped-classroom/Accessed November 10, 2017

- SteeleGECreating a Flipped Advising ApproachNACADA Academic Advising Resources2016 Available from: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Creating-a-Flipped-Advising-Approach.aspxAccessed November 11, 2017

- RobbinsRAdvisor LoadNACADA Academic Advising Resources2013 Available from: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Advisor-Load.aspxAccessed November 11, 2017

- McLaughlinJERothMTGlattDMThe flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions schoolAcad Med201489223624324270916

- LeonardMJAdvising Delivery: Using TechnologyAcademic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook2008292306San Francisco, CAJossey Bass

- MerlinCFlipping the counseling classroom to enhance application based learning activitiesJ Counsel Prep Superv201683128

- FultonCGonzalezLMaking career counseling relevant: enhancing experiential learning using a “Flipped” course designJ Counsel Prep Superv201572130