Abstract

Background and Aim

Loneliness is a common problem in older adults and contributes to poor health. This scoping review aimed to synthesize and report evidence on the effectiveness of interventions using social robots or computer agents to reduce loneliness in older adults and to explore intervention strategies.

Methods

The review adhered to the Arksey and O’Malley process for conducting scoping reviews. The SCOPUS, PUBMED, Web of Science, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ACM Digital Library and IEEE Xplore databases were searched in November, 2020. A two-step selection process identified eligible research. Information was extracted from papers and entered into an Excel coding sheet and summarised. Quality assessments were conducted using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Results

Twenty-nine studies were included, of which most were of moderate to high quality. Eighteen were observational and 11 were experimental. Twenty-four used robots, four used computer agents and one study used both. The majority of results showed that robots or computer agents positively impacted at least one loneliness outcome measure. Some unintended negative consequences on social outcomes were reported, such as sadness when the robot was removed. Overall, the interventions helped to combat loneliness by acting as a direct companion (69%), a catalyst for social interaction (41%), facilitating remote communication with others (10%) and reminding users of upcoming social engagements (3%).

Conclusion

Evidence to date suggests that robots can help combat loneliness in older adults, but there is insufficient research on computer agents. Common strategies for reducing loneliness include direct companionship and enabling social interactions. Future research could investigate other strategies used in human interventions (eg, addressing maladaptive social cognition and improving social skills), and the effects of design features on efficacy. It is recommended that more robust experimental and mixed methods research be conducted, using a combination of validated self-report, observational, and interview measures of loneliness.

Introduction

Loneliness is a growing public health issue that disproportionately affects older adults.Citation1–Citation3 Its global prevalence has been projected to increase in the coming decades as the population ages,Citation4 and this may place a substantial burden on healthcare systems.Citation2 Loneliness is a subjective psychological state where a person perceives a mismatch between their actual and ideal social relations.Citation5 It includes a set of cognitions and emotions that can perpetuate feelings such as perceived problems with social skills and support, reduced self-esteem and optimism, and increased feelings of anxiety, anger, and shyness.Citation6

Loneliness is highly prevalent in older adults,Citation2,Citation3 which may be due to disability-related barriers to social interaction and more time spent living as widowers.Citation4 Older adults experience a shrinking social network size,Citation7 and typically have a lower digital literacy to use social media and other forms of communication technology. More recently, lockdowns of long-term care facilities as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response have amplified feelings of loneliness for many older adults as social visits were restricted.Citation8

A growing body of research suggests that chronic loneliness can negatively affect the immune system and long-term health. Loneliness has been associated with increased feelings of distress, which may activate the body’s “fight or flight” response.Citation9 As part of this response, the sympathetic nervous system is activated and when this is maintained over a prolonged period, the body experiences dysregulation of the immune system. Chronic loneliness has been associated with several physical signs of an impaired immune response, including increased circulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (especially interleukin-6),Citation10 abnormal ratios of circulating white blood cells (eg, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes),Citation11 and under-expression of genes that contribute anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid response elements.Citation12 Chronic loneliness has also been associated with poorer antibody responses to an influenza vaccineCitation13 and the Epstein-Barr virus.Citation14

Chronic loneliness has been shown to increase the risk of long-term health issues, including stress-related physical morbidity (eg, coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke),Citation15 neurological conditions (eg, cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease progression),Citation16–Citation18 and psychiatric conditions (eg, major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, generalized anxiety).Citation19 Loneliness also increases mortality risk.Citation20

A range of psychosocial interventions have been shown to be effective at improving loneliness in older adults.Citation4,Citation21,Citation22 These interventions typically target one of the four areas: (1) modifying maladaptive social cognition, (2) improving social support, (3) increasing opportunities for social interaction, and (4) enhancing social skills. Loneliness interventions can be delivered in-person or facilitated remotely through telephones or computers, and both have shown to be effective for older adults.Citation4 The review concludes that the power of technology has yet to be harnessed.Citation4

Research is beginning to show that artificial agents, such as social robots and computer agents, may be effective ways to deliver loneliness interventions to older adults. The definition of a social robot is discussed by Hegel et alCitation23 and is described as a robot with a social interface (a robot is a programmed physical entity that perceives and acts autonomously within a physical environment that has an influence on its behaviour). Social robots often resemble animals or humans, and several have been shown to improve loneliness in older adults.Citation24,Citation25 Animal-like social robots may improve loneliness in a similar way to animal-assisted therapy, by providing emotional support and increasing social interaction. Animal robots are more scalable and suitable to hospitals or environments with social restrictions than real animals. Other social robots have supported older adults with daily healthcare and companionship needs using touch-screen interactions,Citation26 and more recently with assessment interviews in care pathways using verbal conversational abilities.Citation27

Computer agents are screen-based, computer-generated entitiesCitation28 that may include a dialogue system and a digital embodiment (eg, an animation of a human face on a screen).Citation29 Examples include embodied conversational agents, virtual agents, digital humans, and game characters. Virtual agents (sometimes referred to as digital agents) are a form of embodied conversational agent that may include sophisticated social interaction abilities and an elaborate cognitive architecture.Citation30 Many computer agents are capable of engaging in complex conversations which may enable them to deliver a broad range of psychological interventions for loneliness, akin to a human therapist. Computer agents have been shown to help reduce loneliness in older adults by using daily conversations for emotional support, teaching stress management skills, and engaging in casual chit-chat.Citation31,Citation32

The objective of this scoping review was to synthesize and report evidence on the effectiveness of interventions using social robots and computer agents to reduce loneliness in older adults. Prior review papers have focused on the effects of a broad range of psychosocial interventions on older adult loneliness,Citation21,Citation22,Citation33 or on the effects of social robots in older adult healthcare more broadly.Citation34–Citation38 No reviews to date have collated the evidence on social robots and computer agents specifically for reducing loneliness in older adults. This may help to guide directions for future research and care.

Materials and Methods

A scoping review was conducted to explore and synthesize the available literature related to the topic.Citation39 Scoping reviews cover the breadth of a research topic by summarising prior knowledge through thematic analyses,Citation40 yet are conducted systematically as researchers explicitly describe the literature selection process.Citation41,Citation42

This review was conducted by following the Arksey and O’MalleyCitation40 five-step process for conducting scoping reviews. This includes (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The review is also reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR extension for scoping reviews.Citation43 A protocol was registered with OSF Registries (https://osf.io/dxheu/) in November, 2020.

Identifying the Research Question

An initial search of the literature identified the promise of social robots and computer agents for reducing loneliness in older adults, but an absence of literature collating evidence of effects. This review therefore sought to explore the following research question: How effective are interventions that use social robots or computer agents for reducing loneliness in older adults, and what techniques do they use?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The following bibliographical databases were searched: SCOPUS, PUBMED, Web of Science, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ACM Digital Library and IEEE Xplore. The reference lists of the included literature were also reviewed, to potentially snowball literature that had been missed in the database searches. The search was conducted in November, 2020.

Key terms were determined using the Medical Subject Headers (MeSH terms). Keywords for the population included: “older adult*”, “elder*”, “senior*” and “aged”. Those pertaining to the intervention included “robot*”, “digital agent*”, “virtual agent*” and “computer agent” and the keywords for the outcome included “lonel*”, “companion*”, “social isolation”, “social support”, “social networking”, “social participation” and “social connectivity”. All keywords were separated with the Boolean operator “OR” and each line (population, intervention and outcome) was separated with the operator “AND”. The asterisk (*) symbol allowed for keywords to be treated as prefixes. For example, “robot*” includes the terms “robot”, ‘robots’ and ‘robotics’. Examples of the search terms for two databases are exemplified in .

Table 1 Examples of the Search Terms Used to Locate Literature Within Two Databases

Selecting Studies

Search results were uploaded to CovidenceCitation44 for screening using a two-stage approach. Duplicates were identified and removed by Covidence. Two authors (NG and KL) first independently assessed each article by initially reading the title and abstract, to determine whether articles met the inclusion criteria. The screening process was then repeated a second time, whereby both authors read the full text. Conflicts during each round were identified and discussion resolved any disagreements. A third reviewer (EB) helped to make the final decision, if consensus was not reached. This process was displayed in a PRISMA flowchart.

A study was considered eligible if it was published in English, included a sample of older adults, explored the outcome of loneliness or similar (eg social connection, social networks or reduced isolation) and where the intervention was a social robot or a computer agent (as identified by the study authors). Older adults were defined as 50 years or older, as changes (eg bereavement, loss of social roles, reduced social networks and cognitive decline) during the second half of life may exacerbate loneliness.Citation4,Citation7,Citation45 No restrictions were set on the research method, date, setting or methodological quality. Thus, experiments, pilot studies, feasibility studies, qualitative and observational studies were included. Given that research was not limited by methodological quality, refereed full-length conference papers and theses were included in addition to peer-reviewed journal articles.

Charting the Data

Two authors (NG and ML) extracted the following information into a charting sheet on Excel: author/date, robot or computer agent used, setting, sample age, sample gender, sample size, study duration, study design (eg experiment, observation, interviews), effect size and outcome/results (regarding loneliness).

Quality assessments were conducted using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).Citation46 The MMAT was deemed appropriate as it provides a consistent tool for evaluating qualitative, quantitative randomised controlled trials, quantitative non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive and mixed-methods research. Each study was assessed independently by two authors (NG and ML), and a discussion ensued about their quality. Consensus was reached on methodological limitations, and these were synthesised and described.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Results in the charting sheet were summarised and presented in tables. The focus of the research topic was examined in detail, including the intervention strategies and how effectively the interventions impacted loneliness in older adults. Other information extracted included the context/settings of the research, interventions used and the quality of the research. This information helped to identify gaps in knowledge to inform future research.

Results

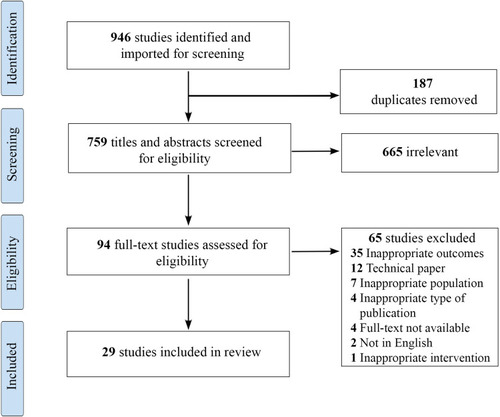

In this review, 946 studies were identified and imported into Covidence for screening. After deduplication, the abstracts and titles of 759 studies were independently reviewed for eligibility by two authors (NG and KL). The full-text of 94 studies were then reviewed by both authors, revealing that 65 studies were no longer eligible to be included. Reasons for exclusion were inappropriate outcomes (n=35) (ie, those not related to loneliness), technical papers (n=12), inappropriate population (n=7) (eg, younger adults or children), inappropriate type of publication (n=4) (eg, posters or conference abstracts), full-text not available (n=4), not in English (n=2) and inappropriate intervention (n=1) (ie, not robots nor computer agents). Twenty-nine studies were included in this review. The PRISMA-ScR flowchart in shows the identification and screening process.

Figure 1 PRISMA-ScR flowchart showing study identification and screening process.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Eighteen studies were observationalCitation26,Citation32,Citation47–Citation62 and 11 were experimental.Citation24,Citation25,Citation31,Citation63–Citation69 One was part of a larger RCT.Citation70 Ten studies were conducted in the United States of America,Citation24,Citation31,Citation32,Citation47,Citation51,Citation59,Citation60,Citation62,Citation66,Citation69 five in New Zealand,Citation26,Citation64,Citation65,Citation68,Citation70 three in AustraliaCitation54,Citation55,Citation61 and two in Germany.Citation49,Citation50 The remaining studies were conducted in Ireland,Citation63 Taiwan,Citation25 Canada,Citation57 Israel,Citation67 Norway,Citation52 JapanCitation53 and Finland.Citation56 CoşarCitation58 and D’OnofrioCitation48 each conducted their studies across three countries (Greece, UK and Poland, and Italy, UK and Ireland respectively).

Across the studies, sample sizes varied from five to 95 participants, with a mean of 22 and an overall total of 632 participants. On average, participants were aged between 62Citation62 and 85.8 years.Citation58 Women participated more than men and the percentage of female participants ranged from 50%Citation49 to 100%.Citation47 Characteristics of the included studies are further summarised in .

Table 2 Characteristics and Summary of the Included Research

Quality of the Included Studies

The MMATCitation46 considers five specific criteria related to methods (eg, methodological approach, research questions, data collection and analysis) and presentation of findings for each of the five study designs. These include criteria such as whether the qualitative approach is appropriate to answer the research question in the qualitative study design, and whether randomisation was appropriately performed in the quantitative RCT study design.

Cohen’s kappa was calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23) to determine interrater reliability between the two authors (NG and ML) conducting the quality assessments. There was moderate agreement between the two raters, κ = 0.592 (95% CI, 0.435 to 0.749, p < 0.0005), with 86% agreement (124/145). Absolute agreement on the MMAT quality criteria was then reached through discussion.

Supplementary Table 1 presents the quality assessments of each study. Overall, eight studies met all five criteriaCitation25,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50,Citation51,Citation55,Citation57,Citation61,Citation70 and 12 met four criteriaCitation26,Citation31,Citation32,Citation50,Citation52–Citation54,Citation60,Citation63–Citation65,Citation67,Citation68 demonstrating moderate to high quality. The qualitative approach or analysis method were not reported for eight mixed methods studiesCitation50,Citation54,Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation62,Citation64,Citation66,Citation69 and the rationale for using mixed methods was also not provided by five.Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation62,Citation66,Citation69 In five studies that were either solely randomised controlled trials or RCTs in addition to mixed methods, blinding was either not possible, or not conducted.Citation24,Citation64–Citation66,Citation68 Five studies indicated possible incomplete data, or nonresponse bias or retention of less than 80% of participants, resulting in incomplete data.Citation26,Citation52,Citation60,Citation65,Citation66 For three quantitative non-randomised studies, confounding factors (eg imbalance of gender or use of robot across groups) may have not been accounted for.Citation32,Citation53,Citation63

Interventions Studied

Types of Interventions

Twenty-four studies investigated the effects of a social robot on loneliness outcomes. The most commonly used robot was the seal companion robot, Paro, which was investigated in six studies.Citation25,Citation52,Citation65,Citation68–Citation70 AIBO,Citation24,Citation53 MARIOCitation48,Citation63 and iRobiCitation26,Citation64 were investigated in two studies each, and the remainder of the robots were investigated in one study (see ). Five studiesCitation31,Citation32,Citation47,Citation62,Citation66 used virtual agents. Two used Care Coach,Citation32,Citation47 two used TanyaCitation31,Citation62 and the final study investigated differences between the AlwaysOn System delivered as both a virtual agent and a robot.Citation66

Length of Interventions

As shown in , the study durations ranged widely from 10-minute sessions, to up to 1 year. The studies also varied widely on whether the participants had time-limited sessions over the study duration, or whether the participants had unlimited 24/7 access to the robot or computer agent over the study period. Therefore, exposure to the interventions was mixed across studies.

Settings and Participants

The majority of studies took place in retirement homes and long-term care facilities (n=20). Six studies were conducted within participants’ homes,Citation26,Citation31,Citation51,Citation55,Citation62,Citation66 two within laboratory settingsCitation57,Citation67 and one was conducted in a hospital.Citation32 All 29 studies were conducted with older adults, with five studies specifically focusing on older adults with dementia,Citation48,Citation59,Citation61,Citation63,Citation65 and one on older adults with Alzheimer's disease.Citation57

Loneliness Measures

Loneliness was measured through both qualitative and quantitative data. At baseline, older adults in many studies did not need to meet specific criteria related to loneliness, to participate.Citation25,Citation26,Citation32,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50,Citation52–Citation58,Citation60,Citation61,Citation63–Citation65,Citation67–Citation70 In others, participants were included if they lived alone.Citation31,Citation49,Citation59,Citation62,Citation66 Few studies used validated measures to identify lonely individuals to participate.Citation24,Citation51

Seventeen studies used mixed methods,Citation25,Citation26,Citation31,Citation47,Citation49,Citation54–Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64–Citation67,Citation69 eight were quantitativeCitation24,Citation32,Citation48,Citation52,Citation53,Citation60,Citation63,Citation68 and four were qualitative.Citation50,Citation51,Citation57,Citation70 The majority of studies used semi-structured interviews with the users (n=17) or caregivers/staff (n=3) to obtain qualitative data about loneliness and social support changes. Eleven studies reported observations of the user while interacting with the robot or computer agent, and three recorded the conversations that took place between the user and the robot.Citation48,Citation59,Citation62 The quantitative measures included; the 20-item (n=6) and 3-item (n=2) UCLA Loneliness Scale,Citation71 the modified Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (MLAPS; n=1),Citation72 the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS; n=1),Citation73 the Ando-Osada-Kodama (AOK) Loneliness Scale (n=1),Citation74 the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (NSSQ; n=1)Citation75 and the Relationship Closeness Inventory (n=1).Citation76 Lastly, four studies used surveys of acceptability and attitudes of the robots as indicators of possible relationships formed between the user and robot/agent.

Effect of Interventions on Loneliness

Positive Effects

The majority of the studies found positive effects of social robots or computer agents on at least one of the loneliness outcome measures, as shown in and summarised below. No substantial differences were found in the effects on loneliness between the studies of people living with dementia/Alzheimer’s disease and studies of cognitively intact people. Therefore, these results are discussed together.

Six of the seven studies that measured loneliness with the UCLA Loneliness Scale (either the 20 or three-item version) found that interacting with AIBO,Citation24 Paro,Citation25,Citation68 NAO,Citation60 TanyaCitation31 or the Care Coach AvatarCitation32 significantly decreased loneliness levels. The other study only used the UCLA to measure loneliness at baseline.Citation62 Loneliness, as measured by the AOK Loneliness Scale, was also found to be significantly lower after interaction with AIBO.Citation53 However, SidnerCitation66 found no significant difference in loneliness, as rated by the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale, between the control groups and the AlwaysOn system as either a robot or virtual agent. Despite this, interviews demonstrated that the intervention provided companionship to some participants. The lack of significant effects in the statistical analysis may be due to lack of power given the small sample size and the authors discuss issues with recruitment.

Other quantitative measures showed similar results. BanksCitation24 found that interacting with AIBO led to an increase in attachment, similar to that of interacting with a dog. Interacting with the MARIO robot led to an increase in perceived social support in particular age groups; however, this was not significant if the sample as a whole was examined.Citation48 RingCitation31 found that interacting with a proactive conversational agent decreased self-reported loneliness and increased comfort and relationship with the agent; outcomes which were significantly correlated with the time spent interacting with the agent. Lastly, surveys on acceptability found that users were highly satisfied with the Tanya agentCitation31,Citation62 and liked interacting with the robots, saw them as companions or friends, and wanted to continue interacting with them in the future, indicating relationships with the robots were formed.Citation55,Citation59

Cohen’s d values are reported as estimates of effect sizes for seven studies (see ). If not reported in the articles, Cohen’s d values were calculated from means and standard deviations reported. The Cohen’s d values ranged from 0.36 to 2.50 indicating a large range from small to large effects. Sub-analyses of these effect sizes for measures and robot/agent type were unable to be conducted due to the low number of studies with available effect sizes. Effect sizes could not be included from qualitative measures (n=19), from studies that did not repeat measures (n=1) or those that did not report means and standard deviations (n=2).

The qualitative findings indicated that the robots and computer agents were able to decrease loneliness and increase social support and companionship, as indicated by interviews with direct users. Many thought of the robots/agents as social beings that they could communicate with, rather than machines.Citation47,Citation50,Citation51,Citation62 Users reported that when the robot or agent was present, they felt there was “someone” there for them and “someone” to talk to, which made them feel less alone.Citation26,Citation31,Citation51,Citation58,Citation66,Citation67 This was particularly evident in the animal-like companion robots (eg Paro and the Joy for All pets) as direct interaction reduced feelings of loneliness and gave them a sense of comfort.Citation25,Citation51 Others commented that the robot/agent was more available and less judgmental than humans.Citation66 Supplementary interviews with caregivers supported these findings, in which social connections were perceived to have formed between the robots and users.Citation57,Citation59

Within the interviews, it was evident that users were prompted to engage with others when the robot or agents were present, thus leading to an increase in social interactions. Many users noted increased conversations with others, as well as forming new social connections.Citation25,Citation51 Social interactions with family were also increased when participants used the video calling functions.Citation56,Citation61 However, users in Orejana’sCitation26 study noted that the iRobi robot had little influence on external social connections and the Skype application was not widely used. This was because most users already had other virtual means of communication with their families. Therefore, the inclusion of virtual communication technology does not necessarily lead to an increase in social connections and decreased loneliness.

Observations of human-robot interaction indicated that users formed social connections and emotional attachments with the robots, akin to the findings from the interviews. Multiple studies observed an increase in users’ positive emotions and facial expressions while interacting with the robots.Citation55,Citation65 Many users were observed to express affection towards the robots, including naming them, having conversations with them, and treating them as pets or friends.Citation65,Citation69,Citation70 The users’ interest in interacting and speaking with the robots also did not appear to decline over time indicating relationship formation, rather than just novelty.Citation59

Observations reflected an increase in the number and intensity of conversations and engagements between people (including staff, family and other residents) when the robot was present, compared to when it was not.Citation63,Citation65,Citation68–Citation70 The degree of positive emotions towards others, including smiling and laughing with others, was also increased.Citation52,Citation65 One study found that this increase in social interaction was observed whether the participant was directly using the Paro robot, or not.Citation52 This indicates that the mere presence of a robot may increase social interaction.

Negative Effects

Some studies mentioned unintended negative consequences of robots and computer agents on social outcomes. Four reported that users had negative reactions, including sadness and regret, to the robots being taken away at the end of the study period.Citation25,Citation50,Citation58,Citation59 ChenCitation25 also reported that users were disengaged and reported increased loneliness after the removal of the Paro robot. Three studies mentioned that users had increased anxiety or frustration during use, especially when the robot was not doing what they expected it to.Citation55,Citation63,Citation64 In one study, a user reported feeling worse during the time that she interacted with the agent, as it made her realise that she lacked friends.Citation62 Similarly, another study mentioned that an in-home robot and/or computer agent was disruptive for users as they felt it was an inconvenience to have to interact with it every day.Citation66

Further issues were raised in studies with older adults with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in particular. One issue was that the use of robots may not relieve caregiver burden as hoped. For example, LiangCitation65 mentioned that some caregivers of people living with dementia felt like they had to supervise interactions with the Paro robot. Concern was also raised about whether some users were capable of caring for their robots by themselves, especially the Paro robot, and whether this may cause further frustration.Citation69 BarrettCitation63 found that negative content, such as news stories and photos of deceased relatives, could increase negative emotions in patients living with dementia. Lastly, WangCitation57 suggested that robots could replace human contact and result in possible family neglect for people with Alzheimer’s disease. This was exemplified by a user who enjoyed doing menial tasks (eg household chores) with their husband and believed that the robot might replace this meaningful social contact.

Techniques for Reducing Loneliness

Across the research, four main strategies to combat loneliness were evident. These included the robot or agent acting as a direct companion to the user (69%, 20/29), acting as a catalyst for social interaction (41%, 12/29), facilitating remote communication with others (10%, 3/29) and reminding users of upcoming social engagements (3%, 1/29). Seven studies used two strategies, and 22 used one (see ).

Direct Companionship

In 20 studies, the robots or agents acted directly as companions to users, to help reduce loneliness.Citation24–Citation26,Citation31,Citation32,Citation47–Citation51,Citation55,Citation57–Citation60,Citation62,Citation64,Citation66,Citation67,Citation70 Companionship was established through physical interactions with robots, including petting, cuddling, stroking, grooming, sleeping with, sitting next to or holding it while watching television.Citation25,Citation50,Citation51 The physical presence of robots also helped to establish companionship.Citation25,Citation26,Citation51 Participants described that having the robot “waiting” for them at home helped to alleviate loneliness.Citation25,Citation56 However, companionship was also formed with computer agents on a screen, without a physical form outside the screen.Citation31,Citation47,Citation62 In a direct comparison, there was a trend for users to trust a robot more than an agent, possibly due to the robot’s physical interaction abilities.Citation66

The responsiveness and proactiveness of the robot or agent are important factors. Many users spoke to the robot or agent,Citation25,Citation31,Citation47,Citation50,Citation58,Citation59,Citation62,Citation66 even though in some cases they did not receive a response.Citation25,Citation50 However, robots interacted with users in other ways, by lighting up,Citation26 making face tracking motions,Citation66 moving and gesturing,Citation67 making noisesCitation25,Citation69 or even verbally addressing users.Citation49 Conversation topics reported by GrossCitation50 included praising the robot, ranting to it, caring for and enquiring about its condition and asking for its opinion. Conversations with computer agent Tanya included the weather, family and future plans.Citation31,Citation62 A participant in ChenCitation25 reflected that speaking to Paro helped them to alleviate boredom as well as loneliness. Proactiveness (the agent initiating a conversation) was a technique that reduced loneliness compared to passivity (the agent only responding).Citation31

Consequently, participants in many studies were able to form an emotional attachment and deep connection to the robots and computer agents.Citation24,Citation25,Citation49–Citation51,Citation58,Citation59,Citation70 Many even described and treated it as a friend,Citation31,Citation55,Citation57,Citation64,Citation70 family memberCitation26 or their pet.Citation51,Citation70 In a study by Hudson,Citation51 the robot acted as a proxy for a conversational partner for older adults who lived alone and helped a participant to adjust after the loss of a partner. However, participants in other studies accepted that the robot could not replace human companionshipCitation59 and were aware that it was a machine.Citation50,Citation57 In a study with the Care Coach agent, some participants reported the relationship to be superficial, due to its limited conversational ability.Citation47

Catalyst for Social Interaction

One agentCitation47 and 11 robot interventionsCitation25,Citation51–Citation54,Citation58,Citation63,Citation65,Citation68–Citation70 helped to combat loneliness by acting as a catalyst for social interaction. Participants socially connected with staff members, neighbors, other residents and researchers while using the robots, such as by talking about it or showing the robot and its functions to others.Citation25,Citation51–Citation53,Citation63,Citation65,Citation68–Citation70 For example, participants using the MARIO robot showed their photographs from the My Memories function to others.Citation63 The robots and agents were also a topic of conversation with family membersCitation47,Citation63 and participants reported that family and friends were more willing to visit when the robot was present.Citation58

The robots also acted as a catalyst to interact and converse with other people, outside of familiar social networks.Citation25,Citation53 HudsonCitation53 highlighted that people who were shy or previously felt uncomfortable interacting with unknown people found the robot to be effective in helping forge new connections. The impact of increased social interaction was reported to be strong, with one studyCitation70 stating that the reduction of loneliness was attributed to increased social communication, rather than companionship. Additionally, within group sessions with Paro, participants did not need to have the robot on their laps or be using it, to contribute to conversations.Citation52 The presence of Paro within the group simply increased social interaction.

Facilitate Remote Communication

Three robot interventions facilitated remote communication and social interaction with family members using Skype and video-calling.Citation56,Citation61,Citation64 Two of the robots (Giraff and Double) were labelled as telepresence robots, with the sole purpose of reducing social isolation by enhancing engagement between family and older adults in aged-care facilities.Citation56,Citation61 The video function was reported to facilitate a stronger social connection than a phone call,Citation56 and enabled older adults to virtually “visit” family members who lived far away and whom they had not seen for some time.Citation61

Reminders of Upcoming Social Interactions

Providing reminders of social interaction were used in one study as a technique for reducing loneliness.Citation49 The robot SYMPARTNER kept users socially active, by reminding them of their schedules, including social engagements.

Discussion

This scoping review systematically searched for and identified research on interventions that attempted to reduce loneliness in older adults, by using robots or computer agents. The review found that robots were the most commonly used intervention, with the Paro robot being the most popular. This finding has been reported in previous literature reviews on socially assistive robots for broader outcomes.Citation35,Citation77 Indeed, Paro is so popular that researchers now commonly use “Paro” as a keyword when searching for studies on companion robots.Citation35,Citation38 Nevertheless, 18 other robots and three computer agents were used in interventions in this review.

The review answered our research question: how effective are interventions that use social robots or computer agents for reducing loneliness in older adults and what techniques do they use? We found that the majority of interventions positively impacted at least one loneliness outcome; however, unintended negative consequences on social outcomes were also reported in some studies.Citation25,Citation50,Citation58,Citation59 Direct companionship was the most commonly reported strategy (69%), followed by acting as a catalyst for social interaction (41%), facilitating remote communication with others (10%), and sending reminders for social interaction (3%). Overall, the majority of the research was observational in nature, using mixed methods and ranging from moderate to high quality.

Overall Effectiveness of the Interventions

The review supports the effectiveness of using social robots to reduce loneliness in older adults. The majority of the quantitative research demonstrated significant decreases in loneliness for robots, although only two of the five studies on computer agents found significant quantitative effects. However, qualitative data consistently showed that the robots and agents increased companionship and facilitated social interactions for at least some individuals. These findings are consistent with research on loneliness interventions in older adult populations that have human delivery, in which interventions focused on enhancing social support and facilitating social interactions have been shown to be effective (eg, telephone support, shared activities and hobby groups, internet skills training).Citation78–Citation80

Other intervention strategies have been shown to improve loneliness in older adults, but these have yet to be tested with robot or computer agent delivery. Modifying maladaptive social cognition through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is the most effective therapeutic technique for alleviating loneliness.Citation4,Citation81 This involves teaching people to identify and change negative automatic thoughts related to loneliness, social interaction and relationships,Citation81 and behavioral techniques to cope with loneliness-related distress, such as mindfulness.Citation82 Additionally, social skills interventions have included techniques such as learning to express appreciation and develop new or existing friendships.Citation83,Citation84 These strategies could be integrated into robots or computer agents.

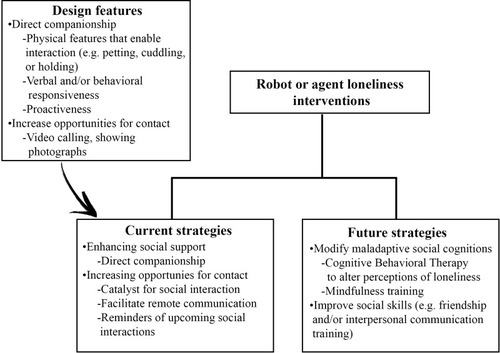

summaries the current strategies used by robots or agents (predominantly focused on enhancing social support and increasing opportunities for social contact), and strategies that could be added in the future (addressing maladaptive social cognitions and improving social skills). also highlights design features that can contribute to direct companionship with robots or agents: a body that can be cuddled and stroked during sedentary activities,Citation25,Citation50,Citation51 proactiveness,Citation31 and responsiveness, either verbalCitation49 or behavioral (through lights,Citation26 facial tracking,Citation66 gestures,Citation67 or noises),Citation25,Citation69 as well as features that can increase opportunities for social interaction.

Figure 2 Current strategies used by robots or agents for reducing loneliness in older adults, and possible future strategies. These strategies are enhanced by certain design features, as illustrated.

The key finding of this review is that robots focused on providing direct companionship and acting as a catalyst for social interaction can reduce loneliness. This has also been shown in children and adults with intellectual disabilities.Citation85,Citation86 Paro acted as a catalyst for social interaction between hospitalized children and other patients or staff, and as a direct companion for these children.Citation85 In another study, Paro acted as a direct companion to five adults with severe intellectual disabilities who formed an emotional connection with the robot.Citation86 Similar results have been found with the Huggable Bear robot, which has been shown to serve a social catalyst role between hospitalized children and their parents,Citation87 and to provide direct companionship.Citation88 Robots may also be effective facilitators of social interaction for children; an AV1 telepresence robot was found to help hospitalized children with cancer connect with classmates during remote learning activities.Citation89

Intervention techniques that have been used in other populations could be applicable to older adults and research should explore these areas. Computer agents have been developed to teach social skills to children with autism spectrum disorder,Citation90 including in virtual reality.Citation91 These programs allow children to practice their social skills using an avatar in a safe, virtual environment with real-time feedback. Similar technology could be developed to deliver a social skills intervention to older adults with loneliness.

Within the quantitative findings, a large range of effect sizes was found. This could have been influenced by the different types of robots/agents used, strategies employed, lengths of exposure, and settings, as well as heterogeneous research designs, methods, outcome measures and study sample sizes. Therefore, it remains difficult to fully conclude the degree of effectiveness of robots as an intervention to decrease loneliness in older adults until more standardized RCTs have been conducted. Only five studies investigated the use of a computer agent as an intervention, and therefore conclusions cannot be made about the effectiveness of computer agents in decreasing loneliness, without further research.

Attachment was sometimes used as an outcome measure, and results indicated that some people did form attachments to robots. While low attachment is not the same as loneliness, it has been correlated with loneliness in research with older adults and pets.Citation92,Citation93 Therefore, attachment is a relevant concept to loneliness and warrants further investigation in future studies with older adults and robots.

Ethical Considerations

The reported unintended consequences highlight ethical considerations, particularly for people living with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Some participants felt sadness, regret and guilt when the robots were removed at the end of the study period.Citation25,Citation50,Citation58,Citation59 Similar findings have been reported in other research, whereby participants became distressed when Paro was taken away.Citation61 Therefore, careful consideration of how robots are removed at the end of a study must be provided when designing robotic interventions. This may include a trial withdrawal period to adapt to life without the robot,Citation94 or renting or selling the technologies to users/hospitals after the intervention period has ended. Future work needs to investigate whether these unintended negative effects are transient or have a longer-term impact.

One study used Wizard of Oz methods to control the agent,Citation62 highlighting important considerations on how to maintain user privacy when agents are not autonomous. Some participants reported feeling anxious as they did not know who was behind the interaction and may be listening to the conversation. An additional limitation of the Wizard of Oz method was that the agent was not always available.

Recommendations for Future Research

The heterogeneity of studies prevents conclusions about which strategies were the most effective, and further experimental research is needed to determine this. Other strategies, such as CBT and social skills training, could be investigated. Further research could explore the long-term effects of interventions, and include follow-up.

There is a need for more robust experimental designs through RCTs. Future mixed methods research should focus on improving the robustness of the qualitative component, providing an in-depth description of the specific methodological approach, data collection and analysis methods. A triangulation of loneliness measures could enhance insights into effects, including observations, validated self-report measures, and interviews.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths include following the Arksey and O’MalleyCitation40 process for conducting scoping reviews, reporting the review in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR extension for scoping reviewsCitation43 and formally assessing methodological quality using the MMAT.Citation46 A potential limitation is that research was only included if it was published in English. This may have resulted in the absence of some relevant research published in other languages. No effort was made to extensively look for grey literature or to contact the authors to request more information. Not all sub-types of computer agents were specifically included in the search strategy, meaning that some studies may not have been identified.

Conclusion

Evidence to date suggests that social robots can reduce loneliness in older adults, using features that encourage direct companionship and facilitate social interactions. Little research is available on the effects of computer agents to date.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Elizabeth Broadbent authored/co-authored five studies included in the review. However, Elizabeth did not conduct the quality assessments, so potential conflicts of interest were mitigated. Soul Machines Ltd (a company that makes digital humans) employs Kate Loveys as an intern and contracts Elizabeth Broadbent as a consultant. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):426. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9

- Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):1013–1019. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.30242725790413

- Nicolaisen M, Thorsen K. Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2014;78(3):229–257. doi:10.2190/AG.78.3.b25265679

- Masi CM, Chen H, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(3):219–266. doi:10.1177/108886831037739420716644

- Peplau LA. Perspective on Loneliness. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy. John Wiley; 1982.

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J Res Pers. 2006;40(6):1054–1085. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

- Victor CR, Bowling A. A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older people in Great Britain. J Psychol. 2012;146(3):313–331. doi:10.1080/00223980.2011.60957222574423

- Krendl AC, Perry BL, Isaacowitz DM. The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults’ social and mental well-being. J Gerontol B. 2021;76(2):e53–58. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbaa110

- Weiss RS. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. The MIT Press; 1973.

- Hackett RA, Hamer M, Endrighi R, Brydon L, Steptoe A. Loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in older men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(11):1801–1809. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.01622503139

- Cole SW. Social regulation of leukocyte homeostasis: the role of glucocorticoid sensitivity. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(7):1049–1055. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2008.02.00618394861

- Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Rose RM, Cacioppo JT. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol. 2007;8(9):1–13. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189

- Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):297–306. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.29715898866

- Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Speicher CE, Holliday JE. Stress, loneliness, and changes in herpesvirus latency. J Behav Med. 1985;8(3):249–260. doi:10.1007/BF08703123003360

- Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009–1016. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-30879027091846

- Boss L, Kang D, Branson S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the older adult: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(4):541. doi:10.1017/S104161021400274925554219

- Lara E, Caballero FF, Rico‐Uribe LA, et al. Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(11):1613–1622. doi:10.1002/gps.517431304639

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):234–240. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.23417283291

- Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, et al. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatr. 2017;17(1):97. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316.20668659

- Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Commun. 2018;26(2):147–157. doi:10.1111/hsc.12367

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Perach R. Interventions for alleviating loneliness among older persons: a critical review. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(3):e109–125. doi:10.4278/ajhp.130418-LIT-18224575725

- Hegel F, Muhl C, Wrede B, Hielscher-Fastabend M, Sagerer G. Understanding social robots. 2009 Second International Conferences on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions; 2009; 169–174.

- Banks MR, Willoughby LM, Banks WA. Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: use of robotic versus living dogs. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(3):173–177. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.00718294600

- Chen S, Moyle W, Jones C, Petsky H. A social robot intervention on depression, loneliness, and quality of life for Taiwanese older adults in long-term care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(8):981–991. doi:10.1017/S104161022000045932284080

- Orejana JR, MacDonald BA, Ahn HS, Peri K, Broadbent E. Healthcare robots in homes of rural older adults. International Conference on Social Robotics; Springer; 2015.

- Boumans R, van Meulen F, van Aalst W, et al. Quality of care perceived by older patients and caregivers in integrated care pathways with interviewing assistance from a social robot: noninferiority randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e18787. doi:10.2196/1878732902387

- Powers A, Kiesler S, Fussell S, Torrey C. Comparing a computer agent with a humanoid robot. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction. 2007; 145–152.

- Cassell J, Sullivan J, Churchill E, Prevost S. Embodied Conversational Agents. MIT Press; 2000.

- Youssef AB, Chollet M, Jones H, et al. Towards a socially adaptive virtual agent. In: Brinkman A, editor. International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents. Cham: Springer; 2015:3–16.

- Ring L, Shi L, Totzke K, Bickmore T. Social support agents for older adults: longitudinal affective computing in the home. J Multimodal User Interf. 2015;9(1):79–88. doi:10.1007/s12193-014-0157-0

- Bott N, Wexler S, Drury L, et al. A protocol-driven, bedside digital conversational agent to support nurse teams and mitigate risks of hospitalization in older adults: case control pre-post study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(10):e13440. doi:10.2196/1344031625949

- Jarvis M, Padmanabhanunni A, Balakrishna Y, Chipps J. The effectiveness of interventions addressing loneliness in older persons: an umbrella review. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2020;12:100177. doi:10.1016/j.ijans.2019.100177

- Abdi J, Al-Hindawi A, Ng T, Vizcaychipi MP. Scoping review on the use of socially assistive robot technology in elderly care. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e018815. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018815

- Pu L, Moyle W, Jones C, Todorovic M. The effectiveness of social robots for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Gerontologist. 2019;59(1):e37–51. doi:10.1093/geront/gny04629897445

- Bemelmans R, Gelderblom GJ, Jonker P, de Witte L. socially assistive robots in elderly care: a systematic review into effects and effectiveness. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(2):114, 120.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2010.10.002

- Kachouie R, Sedighadeli S, Khosla R, Chu M. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: a mixed-method systematic literature review. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2014;30(5):369–393. doi:10.1080/10447318.2013.873278

- Broekens J, Heerink M, Rosendal H. Assistive social robots in elderly care: a review. Gerontechnology. 2009;8(2):94–103. doi:10.4017/gt.2009.08.02.002.00

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-6920047652

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–150. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

- Paré G, Trudel M, Jaana M, Kitsiou S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: a typology of literature reviews. Inf Manag. 2015;52(2):183–199. doi:10.1016/j.im.2014.08.008

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi:10.7326/M18-085030178033

- Covidence, Systematic review software, Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; 2021. Available from: www.covidence.org. Accessed 420, 2021.

- Lee SL, Pearce E, Ajnakina O, et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: a 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;8(1):48–57. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30383-7

- Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Info. 2018;34(4):285–291.

- Chi NC, Sparks O, Lin SY, Lazar A, Thompson HJ, Demiris G. Pilot testing a digital pet avatar for older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38(6):542–547. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.04.00228479082

- D’Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Raciti M, et al. MARIO project: validation and evidence of service robots for older people with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;68(4):1587–1601. doi:10.3233/JAD-18116530958360

- Gross H, Scheidig A, Müller S, Schütz B, Fricke C, Meyer S. Living with a mobile companion robot in your own apartment-final implementation and results of a 20-weeks field study with 20 seniors. 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); IEEE; 2019.

- Gross H, Mueller S, Schroeter C, et al. Robot companion for domestic health assistance: implementation, test and case study under everyday conditions in private apartments. 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); IEEE; 2015.

- Hudson J, Ungar R, Albright L, Tkatch R, Schaeffer J, Wicker ER. Robotic pet use among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol B. 2020;75(9):2018–2028. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbaa119

- Jøranson N, Pedersen I, Rokstad AMM, Aamodt G, Olsen C, Ihlebæk C. Group activity with Paro in nursing homes: systematic investigation of behaviors in participants. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(8):1345–1354. doi:10.1017/S104161021600012027019225

- Kanamori M, Suzuki M, Oshiro H, et al. Pilot study on improvement of quality of life among elderly using a pet-type robot. Proceedings 2003 IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation. Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation for the New Millennium. IEEE; 2003.

- Khosla R, Chu M. Embodying care in Matilda: an affective communication robot for emotional wellbeing of older people in Australian residential care facilities. ACM Transact Manag Info Syst. 2013;4(4):1–33. doi:10.1145/2544104

- Khosla R, Chu M, Khaksar SMS, Nguyen K, Nishida T. Engagement and experience of older people with socially assistive robots in home care. Assist Technol. 2019;1–15.

- Niemelä M, Van Aerschot L, Tammela A, Aaltonen I, Lammi H. Towards ethical guidelines of using telepresence robots in residential care. Int J Soc Robot. 2019;1–9.

- Wang RH, Sudhama A, Begum M, Huq R, Mihailidis A. Robots to assist daily activities: views of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(1):67–79. doi:10.1017/S104161021600143527660047

- Coşar S, Fernandez-Carmona M, Agrigoroaie R, et al. ENRICHME: perception and interaction of an assistive robot for the elderly at home. Int J Soc Robot. 2020;12(3):779–805. doi:10.1007/s12369-019-00614-y

- Abdollahi H, Mollahosseini A, Lane JT, Mahoor MH. A pilot study on using an intelligent life-like robot as a companion for elderly individuals with dementia and depression. 2017 IEEE-RAS 17th International Conference on Humanoid Robotics (Humanoids); IEEE; 2017.

- Fields N, Xu L, Greer J, Murphy E. Shall I compare thee … to a robot? An exploratory pilot study using participatory arts and social robotics to improve psychological well-being in later life. Aging Men Health. 2019;1–10.

- Moyle W, Jones C, Cooke M, O’Dwyer S, Sung B, Drummond S. Connecting the person with dementia and family: a feasibility study of a telepresence robot. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-14-724393272

- Vardoulakis LP, Ring L, Barry B, Sidner CL, Bickmore T. Designing relational agents as long term social companions for older adults. International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents; 2012;289–302.

- Barrett E, Burke M, Whelan S, et al. Evaluation of a companion robot for individuals with dementia: quantitative findings of the MARIO project in an Irish residential care setting. J Gerontol Nurs. 2019;45(7):36–45. doi:10.3928/00989134-20190531-0131237660

- Broadbent E, Peri K, Kerse N, et al. Robots in older people’s homes to improve medication adherence and quality of life: a randomised cross-over trial. International Conference on Social Robotics; Springer; 2014.

- Liang A, Piroth I, Robinson H, et al. A pilot randomized trial of a companion robot for people with dementia living in the community. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(10):871–878. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2017.05.01928668664

- Sidner CL, Bickmore T, Nooraie B, et al. Creating new technologies for companionable agents to support isolated older adults. ACM Trans Interact Intell Syst. 2018;8(3):1–27. doi:10.1145/3213050

- Zuckerman O, Walker D, Grishko A, et al. Companionship is not a function: the effect of a novel robotic object on healthy older adults’ feelings of” being-seen”. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020.

- Robinson H, MacDonald B, Kerse N, Broadbent E. The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(9):661–667. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.00723545466

- Kidd CD, Taggart W, Turkle S. A sociable robot to encourage social interaction among the elderly. Proceedings 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. IEEE; 2006.

- Robinson H, Broadbent E, MacDonald B. Group sessions with Paro in a nursing home: structure, observations and interviews. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(2):106–112. doi:10.1111/ajag.1219926059390

- Russell DW. UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_28576833

- Johnson TP, Garrity TF, Stallones L. Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington attachment to pets scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös. 1992;5(3):160–175. doi:10.2752/089279392787011395

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

- Ando T, Osada H, Kodama Y. Constriction of a new loneliness scale and correlated of loneliness middle aged and Aged. J Yokohama Univ Hum Sci. 2000;3:19–27.

- Norbeck JS. The Norbeck social support questionnaire. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1984;20(5):45–57.6536338

- Berscheid E, Snyder M, Omoto AM. The relationship closeness inventory: assessing the closeness of interpersonal relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(5):792–807. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.792

- Mordoch E, Osterreicher A, Guse L, Roger K, Thompson G. Use of social commitment robots in the care of elderly people with dementia: a literature review. Maturitas. 2013;74(1):14–20. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.10.01523177981

- McAuley E, Blissmer B, Marquez DX, Jerome GJ, Kramer AF, Katula J. Social relations, physical activity, and well-being in older adults. Prev Med. 2000;31(5):608–617. doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.074011071843

- Ibarra F, Baez M, Cernuzzi L, Casati F. A systematic review on technology-supported interventions to improve old-age social wellbeing: loneliness, social isolation, and connectedness. J Healthc Eng. 2020;2020:1–14. doi:10.1155/2020/2036842

- Cattan M, Kime N, Bagnall A. The use of telephone befriending in low level support for socially isolated older people–an evaluation. Health Soc Care Commun. 2011;19(2):198–206. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00967.x

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):238–249. doi:10.1177/174569161557061625866548

- Creswell JD, Irwin MR, Burklund LJ, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(7):1095–1101. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.00622820409

- Martina C, Stevens NL. Breaking the cycle of loneliness? Psychological effects of a friendship enrichment program for older women. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(5):467–475. doi:10.1080/1360786060063789316938682

- Martina CM, Stevens NL, Westerhof GJ. Change and stability in loneliness and friendship after an intervention for older women. Ageing Soc. 2018;38(3):435–454. doi:10.1017/S0144686X16001008

- Nakadoi Y. Usefulness of animal type robot assisted therapy for autism spectrum disorder in the child and adolescent psychiatric ward. JSAI International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence; Springer; 2015.

- Wagemaker E, Dekkers TJ, van Rentergem A, Joost A, Volkers KM, Huizenga HM. Advances in mental health care: five N= 1 studies on the effects of the robot seal Paro in adults with severe intellectual disabilities. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2017;10(4):309–320. doi:10.1080/19315864.2017.1320601

- Jeong S, Breazeal C, Logan D, Weinstock P. Huggable: impact of embodiment on promoting verbal and physical engagement for young pediatric inpatients. 2017 26th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); IEEE; 2017.

- Jeong S, Logan DE, Goodwin MS, et al. A social robot to mitigate stress, anxiety, and pain in hospital pediatric care. Proceedings of the Tenth Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction Extended Abstracts. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2015.

- Weibel M, Nielsen MKF, Topperzer MK, et al. Back to school with telepresence robot technology: a qualitative pilot study about how telepresence robots help school‐aged children and adolescents with cancer to remain socially and academically connected with their school classes during treatment. Nurs Open. 2020;7(4):988–997. doi:10.1002/nop2.47132587717

- Nojavanasghari B, Hughes CE, Morency L. Exceptionally social: design of an avatar-mediated interactive system for promoting social skills in children with autism. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery; New York; 2017.

- Ke F, Im T. Virtual-reality-based social interaction training for children with high-functioning autism. J Educ Res. 2013;106(6):441–461. doi:10.1080/00220671.2013.832999

- Krause-Parello CA. Pet ownership and older women: the relationships among loneliness, pet attachment support, human social support, and depressed mood. Geriatr Nurs. 2012;33(3):194–203. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.12.00522321806

- Krause-Parello CA. The mediating effect of pet attachment support between loneliness and general health in older females living in the community. J Community Health Nurs. 2008;25(1):1–14. doi:10.1080/0737001070183628618444062

- Draper H, Sorell T. Ethical values and social care robots for older people: an international qualitative study. Ethics Inf Technol. 2017;19(1):49–68. doi:10.1007/s10676-016-9413-1