Abstract

Purpose

COPD is often associated with various comorbidities that may influence its outcomes. Pneumonia, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer are the major causes of death in COPD patients. The objective of this study is to investigate the influence of comorbidities on COPD by using the Taiwan National Health Insurance database.

Patients and methods

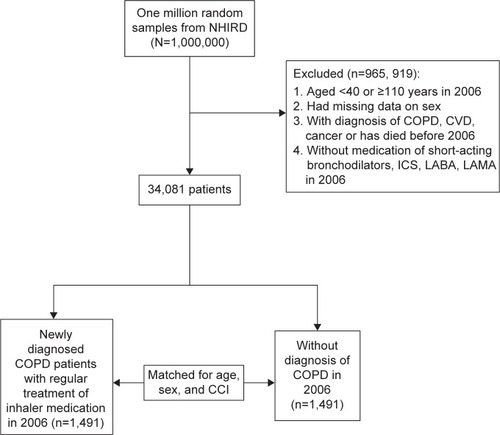

We retrospectively analyzed the database in 2006 of one million sampling cohort. Newly diagnosed patients with COPD with a controlled cohort that was matched by age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) were included for analysis.

Results

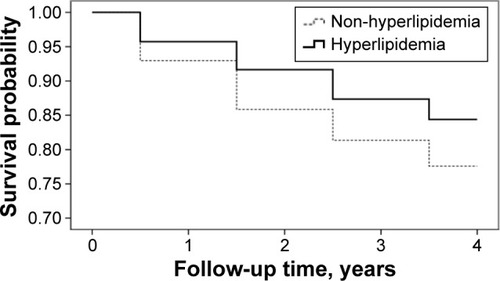

In total, 1,491 patients with COPD were included for analysis (61.8% male). Patients with COPD had higher incidences of pneumonia (25.7% vs 10.4%; P<0.0001), CVD (15.1% vs 10.5%; P<0.0001), and mortality rate (26.6% vs 15.8%; P<0.001) compared with the control group in the 4-year follow-up. In patients with COPD, CCI ≥3 have a higher incidence of pneumonia (hazard ratio [HR] 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23–2.09; P<0.0001), CVD (HR 1.73; 95% CI 1.24–2.41; P=0.001), and mortality (HR 1.12; 95% CI 1.12–1.83; P=0.004). Among the major comorbidities of COPD, hyperlipidemia was associated with decreased incidence of pneumonia (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.5–0.93; P=0.016) and mortality (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.46–0.90; P=0.009), but was not associated with increased risk of CVD (HR 1.10; 95% CI 0.78–1.55; P=0.588).

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that COPD is associated with increased incidence of pneumonia, CVD, and mortality. In patients with COPD, higher CCI is associated with increased incidence of pneumonia, CVD, and mortality. However, COPD with hyperlipidemia is associated with decreased incidence of pneumonia and mortality.

Keywords:

Introduction

COPD is one of the major public health problems in modern society caused mainly by cigarette smoking, and its importance is increasing.Citation1,Citation2 COPD is a complex, heterogeneous, multicomponent disease with great variations in its clinical, radiological, and functional aspects.Citation3 It has a variety of systemic manifestations and thus the current guideline recommends a multidirectional strategy in diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of COPD.Citation4

COPD is often associated with a variety of comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), malignancy, anxiety, depression, chronic renal failure, and infection.Citation5–Citation10 Comorbidities of COPD also have important impacts on major outcomes, including quality of life,Citation11 rate of acute exacerbation,Citation12 and mortality.Citation13 Both COPDCitation14,Citation15 and coronary artery diseaseCitation16 are characterized by low-grade systemic inflammation, which is manifested by increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers. Patients with COPD are at increased risk of hospitalization and mortality due to CVD.Citation17,Citation18 Moreover, patients with more severe COPD have higher cardiovascular mortality and morbidity than those with less severe COPD.Citation19 Although obesity and hyperlipidemia are both risk factors of CVD,Citation20 patients with COPD tend to have lower body mass index (BMI) and are less likely to have hyperlipidemia.Citation21 Most comorbidities are associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with COPD, but in an observational study, the prevalence of hyperlipidemia is higher in survivors than non-survivors.Citation22 Furthermore, as BMI is one of the composite factors of BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity) index score, patients with COPD having lower BMI are associated with increased risk of death.Citation23,Citation24 Thus, the impact of hyperlipidemia on clinical outcomes of patients with COPD is complex and unclear.

The aim of this study is to use nationwide, 5-year population-based data to examine the relationship of major comorbidities on outcomes of COPD, with special interest on hyperlipidemia.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan, maintains the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) and authorizes its use for research purposes. We obtained a subset of the NHIRD with one million random subjects, accounting for ~5% of all subjects enrolled in the National Health Insurance program. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, or health care costs between the sample group and all enrollees (data not shown). The database contains medical claims information regarding ambulatory care, inpatient care, dental services, and prescription drugs as well as insurance data from all subjects between January 1996 and December 2009.Citation25 The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) coding system was incorporated into the data from the beginning of 2000 and was used in this study.

The study was conducted by a retrospective, matched cohort design. Patients with COPD were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: 1) new diagnosis of COPD in the year 2006; 2) older than 40 years of age at the time of diagnosis of COPD; 3) at least three outpatient visits with COPD medication prescription or admission once with main diagnosis of COPD; 4) were prescribed COPD medication, including inhaled short- and long-acting bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids or corticosteroid/long-acting β-agonist combination; 5) lack of diagnosis of cancer, CVD, and COPD from 2000 to 2006. The patients were matched to non-COPD patients by age in 2006, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) of 2005 in a 1:1 fashion (). COPD was defined by ICD-9-CM codes 491 (chronic bronchitis), 492 (emphysema), and 496 (chronic airway obstruction, not elsewhere classified). Major outcomes of COPD, including pneumonia, CVD, cancer, and death were recorded by NHIRD from 2006 to 2009. Cancer was defined by ICD-9-CM codes 140 to 208; pneumonia was defined by ICD-9-CM codes 480 to 486 as the main diagnosis of admission; CVD was defined by ICD-9-CM codes 390 to 438 as the main diagnosis of admission.

Figure 1 Enrollment details.

The major comorbidities, including hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401 to 405), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), diabetes (ICD-9-CM codes 250), chronic renal disease (ICD-9-CM codes 403, 404, 581 to 583, and 585 to 588), and CVD (ICD-9-CM codes 390 to 438) were recorded from inpatient and outpatient database from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2009. As the NHRI made the claim data available in an anonymous format which provided the individuals cannot be identified individually, retrospective studies do not need ethical approval from ethics committees in Taiwan.

Statistical methods

Differences in characteristics of subjects with and without COPD according to age, sex and clinical comorbidities, incidence of pneumonia, CVD, cancer, and death were examined using chi-squared tests for categorical variable and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. The Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test were used to examine the difference in the mortality between patients with COPD with and without hyperlipidemia. The crude and age-, sex-, and CCI- adjusted hazard ratio (HR) in COPD subjects with pneumonia, acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), CVD, cancer, and mortality were calculated. The rate ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) were also calculated. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to explore the relationship between hyperlipidemia and mortality, adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities. The proportional hazards assumption was tested graphically and by including the interaction of time with each covariate. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value of 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects

In total, 2,982 subjects, comprising of 1,491 COPD and 1,491 non-COPD with matched age, sex, and CCI, were included for analysis (). Patients with COPD had a higher risk of developing pneumonia (25.7% vs 10.4%; P<0.0001), CVD (15.1% vs 10.5%; P<0.0001), and rate of mortality (26.6% vs 15.5%; P<0.0001) over the next 4 years. There was no difference for risk of malignancy.

Table 1 Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study subjects

Impact of age, sex, and CCI on major outcome of COPD

Age was associated with increased HR of COPD-related outcomes, including pneumonia (HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.44–1.72; P<0.0001), AECOPD (HR 1.34; 95% CI 1.24–1.44; P<0.0001), CVD (HR 1.53; 95% CI 1.45–1.72; P<0.0001), malignancy (HR 1.17; 95% CI 1.00–1.34; P=0.044), and mortality (HR 2.04; 95% CI 1.85–2.24; P<0.0001) (). Male sex was associated with increased risk of pneumonia (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.25–1.94; P<0.0001), AECOPD (HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.50–2.24; P<0.0001), malignancy (HR 1.70; 95% CI 1.12–2.53; P=0.013), and mortality (HR 1.46; 95% CI 1.18–1.80; P=0.001) over the next 4 years. CCI >3 was associated with increased risk of pneumonia (HR 1.61; 95% CI 1.23–2.09; P<0.0001), CVD (HR 1.73; 95% CI 1.24–2.41; P=0.001), and mortality (HR 1.43; 95% CI 1.12–1.83; P=0.004) over the next 4 years compared with CCI=0.

Table 2 Impact of age, sex, and CCI on major outcomes of COPD

Impacts of major comorbidities on outcomes of COPD

We further investigated the association between major comorbidities and COPD outcome. Age and sex remained important determinants in developing major comorbidities over the next 4 years (). Hyperlipidemia was associated with decreased risk of pneumonia (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.49–0.93; P=0.016), but was not associated with increased risk of CVD (HR 1.09; 95% CI 0.77–1.53; P=0.641). Hyperlipidemia was also associated with decreased risk of mortality (HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.44–0.87; P=0.005). However, diabetes was associated with increased risk of pneumonia (HR 1.37; 95% CI 1.05–1.79; P=0.019), and CVD (HR 1.66; 95% CI 1.20–2.30; P=0.002). Patients with COPD having chronic renal disease (HR 1.66; 95% CI 1.20–2.30; P=0.002) and CVD (HR 1.94; 95% CI 1.23–3.07; P=0.005) were associated with increased mortality.

Table 3 Impacts of major comorbidities on outcomes of COPD

We used Kaplan–Meier survival estimates to compare survival between hyperlipidemia and non-hyperlipidemia in patients with COPD. With regard to the mortality for the 4-year follow-up period, patients with hyperlipidemia were associated with better survival by the log-rank test (<0.01).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that COPD was associated with increased incidence of pneumonia, CVD, and mortality compared with matched subjects. CCI >3 was associated with increased risk of pneumonia, CVD, and mortality in patients with COPD. Among these comorbidities, patients with COPD patients having hyperlipidemia had lower incidence of pneumonia and mortality.

COPD continued to be one of the major threats to human health. In a previous analysis of national mortality and population data of Taiwan, it was found that the mortality rate for COPD increased gradually in the 1990s.Citation26 But the mortality rate of COPD is probably underestimated, as COPD is often underreported on death certificates.Citation27 On comparison with matched control subjects, we found that patients with COPD have increased risk of developing pneumonia, CVD, and mortality. Aging is a worldwide health care problem in the modern society and our results show that age is an independent risk factor for comorbidities and major COPD outcomes. COPD is often associated with a variety of comorbidities and its relationship is complex.Citation28 COPD should be considered as a component of multimorbidity and some common pathways of pathogenesis are suggested.Citation29 Current COPD treatments, both pharmacologicalCitation30 and nonpharmacologialCitation31,Citation32 interventions, can effectively improve lung function, relieve symptoms, prevent exacerbation, and improve quality of life. However, there is an urgent need for treatment to prevent mortality.Citation33,Citation34 Our results once again highlight the association between COPD and comorbidities and thus suggest appropriate managements and prevention of comorbidities that could possibly be the key toward reducing mortality in COPD.

CVD is the leading cause of mortality and hospital admission in COPD patients.Citation35 Long-term use of pharmacological treatment with bronchodilators, including β-2 agonists and anticholinergic agents, may be associated with increased risk to develop cardiovascular complications.Citation23,Citation36–Citation39 Although hyperlipidemia is a well-known risk factor of CVD, our results show that the incidence of CVD was not increased in patients with COPD having hyperlipidemia. On the contrary, the incidence of pneumonia and mortality was lower in patients with COPD having hyperlipidemia. Malnutrition is common in patients with COPD because of increased energy expenditure and decreased intake. The adipose tissue is involved in the development of systemic inflammation of CVD by releasing a wide variety of substances called adipokines.Citation40,Citation41 Dysregulation of adipokines, including leptin and adiponectin with proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory activities, may contribute to the development of systemic inflammation in COPD.Citation42 Since COPD is a heterogeneous disease with different pathogenesis and phenotypes, efforts should be made to clarify the relationship between COPD and hyperlipidemia, from basic science to bedside practice.

Statins are lipid-lowering agents that have been widely used to treat hyperlipidemia and astherosclerotic disease. In addition to lipid-lowering activity, statin has anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and immunomodulation effects.Citation43 In an animal study, simvastatin could ameliorate the structural and functional derangements of the lungs caused by cigarette smoking through reduction of chemokines and metalloproteinases.Citation44 Previous studies have also shown that the use of statin has a beneficial impact on improved airflow limitation,Citation45 lower risk of AECOPD,Citation46 and improved survival after exacerbation in patients with COPD.Citation47,Citation48 However, most of these published studies have inherent methodological limitations due to retrospective studies or population-based analyses. So, there is a need for prospective interventional trials designed specifically to assess the impact of statins on clinically relevant outcomes in COPD.

Strengths and limitations

Investigation of clinical problems by using public health data has the following strengths. First, it includes a large population. Second, it is a real-life data without restrictions in age, economic status, races, concomitant drug treatments, comorbidities, and possibly is more clinical relevant. However, our study may have the following limitations. First, the data is primarily based on financial claims and its quality is questionable in some aspects. Social and behavior characteristics (such as smoking status) and COPD severity are not available. In order to assure the accuracy of diagnosis, we included newly diagnosed patients with COPD on regular treatment with inhaler medication because their claims had been carefully inspected and the diagnosis was supported by laboratory data. Second, although a matched control group was selected for comparison, there could still be possible unknown confounding factors. Third, the diagnosis of the comorbidities, including hyperlipidemia, listed in this study was not confirmed by laboratory and image data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, by using a nationwide health insurance database, this retrospective analysis demonstrates that patients with COPD with hyperlipidemia is not associated with increased incidence of CVD, but is associated with decreased risk of having pneumonia and death. Further investigation, from basic science to clinical investigation, is warranted to clarify the impact of hyperlipidemia on the outcome of COPD.

Author contributions

M-CC, C-HL and YRK contributed to conception and design of the study. M-CC and C-HL drafted the manuscript and performed statistical analysis. M-CC, C-HL and YRK made critical revisions to the manuscript and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (MOST 104-2320-B-010-014-MY3) from Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes (registration number 99278). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

The abstract of this paper was presented at the American Thoracic Society 2013 International Conference, May 17–22, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “Poster Abstracts” in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Vol 187, Meeting Abstracts, 2013.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChenJCManninoDMWorldwide epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCurr Opin Pulm Med19995939910813258

- MurrayCJLopezADAlternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease StudyLancet1997349149815049167458

- ShirtcliffePWeatherallMTraversJBeasleyRThe multiple dimensions of airways disease: targeting treatment to clinical phenotypesCurr Opin Pulm Med201117727821150622

- Global Strategy for Diagnosis Management, and Prevention of COPD – 2016Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)2016 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com/Accessed Feb 17, 2016

- TantucciCCOPD and osteoporosis: something more than a comorbidityEndocrine2012425622581203

- SethiSInfection as a comorbidity of COPDEur Respir J2010351209121520513910

- IncalziRACorsonelloAPedoneCBattagliaSPaglinoGBelliaVExtrapulmonary Consequences of COPD in the Elderly Study Investigators. Chronic renal failure: a neglected comorbidity of COPDChest201013783183719903974

- van den BemtLSchermerTBorHThe risk for depression comorbidity in patients with COPDChest200913510811418689578

- CarratuPRestaOIs obstructive sleep apnoea a comorbidity of COPD and is it involved in chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome?Eur Respir J2008311381138218515563

- ManninoDMAguayoSMPettyTLReddSCLow lung function and incident lung cancer in the United States: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey follow-upArch Intern Med20031631475148012824098

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWThe influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidityJ Clin Epidemiol2003561177118414680668

- TerzanoCContiVDi StefanoFComorbidity, hospitalization, and mortality in COPD: results from a longitudinal studyLung201018832132920066539

- SinDDAnthonisenNRSorianoJBAgustiAGMortality in COPD: role of comorbiditiesEur Respir J2006281245125717138679

- StolzDChrist-CrainMMorgenthalerNGCopeptin, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin as prognostic biomarkers in acute exacerbation of COPDChest20071311058106717426210

- GanWQManSFSenthilselvanASinDDAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysisThorax20045957458015223864

- DaneshJWheelerJGHirschfieldGMC-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart diseaseN Engl J Med20043501387139715070788

- SidneySSorelMQuesenberryCPJrDeLuiseCLanesSEisnerMDCOPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care ProgramChest20051282068207516236856

- CurkendallSMDeLuiseCJonesJKCardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada cardiovascular disease in COPD patientsAnn Epidemiol200616637016039877

- CurkendallSMLanesSde LuiseCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and cardiovascular outcomesEur J Epidemiol20062180381317106760

- GrundySMCleemanJIDanielsSRAmerican Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteDiagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific StatementCirculation20051122735275216157765

- JooHParkJLeeSDOhYMComorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Koreans: a population-based studyJ Korean Med Sci20122790190622876057

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPComorbidities and Risk of Mortality in Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med201218615516122561964

- CelliBRCoteCGMarinJMThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20043501005101214999112

- CaoCWangRWangJBunjhooHXuYXiongWBody mass index and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysisPLoS One20127e4389222937118

- National Health Insurance Research Database Available from: http://nhird.nhir.org.tw/en/index/htmAccessed April 18, 2016

- KuoLCYangPCKuoSHTrends in the mortality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Taiwan, 1981–2002J Formos Med Assoc2005104899315765162

- JensenHHGodtfredsenNSLangePPotential misclassification of causes of death from COPDEur Respir J20062878178516807258

- NegewoNAMcDonaldVMGibsonPGComorbidity in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Investig2015536249258

- BarnesPJMechanisms of development of multimorbidity in the elderlyEur Respir J20154579080625614163

- WoodruffPGAgustiARocheNSinghDMartinezFJCurrent concepts in targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pharmacotherapy: making progress towards personalized managementLancet20153851789179825943943

- SpruitMAPittaFMcAuleyEZuWallackRLNiciLPulmonary rehabilitation and physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med201519292493326161676

- Farver-VestergaardIJacobsenDZachariaeREfficacy of psychosocial intervention on psychological and physical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systemic review and mega-analysisPsychother Psychosom201584375025547641

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSUPLIFT Study InvestigatorsA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20083591543155418836213

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med200735677578917314337

- AnthonisenNRSkeansMAWiseRAManfredaJKannerREConnettJELung Health Study Research GroupThe effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: a randomized clinical trialAnn Intern Med200514223323915710956

- CazzolaMMateraMGDonnerCFInhaled beta2-adrenoceptor agonists: cardiovascular safety in patients with obstructive lung diseaseDrugs2005651595161016060696

- LeeTAPickardASAuDHBartleBWeissKBRisk for death associated with medications for recently diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med200814938039018794557

- MacieCWooldrageKManfredaJAnthonisenNCardiovascular morbidity and the use of inhaled bronchodilatorsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2008316316918488440

- SinghSLokeYKFurbergCDInhaled anticholinergics and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisJAMA20083001439145018812535

- OuchiNParkerJLLugusJJWalshKAdipokines in inflammation and metabolic diseaseNat Rev Immunol201111859721252989

- OuchiNKiharaSFunahashiTMatsuzawaYWalshKObesity, adiponectin and vascular inflammatory diseaseCurr Opin Lipidol20031456156614624132

- BreyerMKRuttenEPLocantoreNWWatkinsMLMillerBEWoutersEFCLIPSEInvestigators(Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints). Dysregulated adipokine metabolism in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur J Clin Invest20124298399122703238

- LiaoJKLaufsUPleiotropic effects of statinsAnnu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol2005458911815822172

- LeeJHLeeDSKimEKSimvastatin inhibits cigarette smoking-induced emphysema and pulmonary hypertension in rat lungsAm J Respir Crit Care Med200517298799316002570

- BandoMMiyazawaTShinoharaHOwadaTTerakadoMSugiyamaYAn epidemiological study of the effects of statin use on airflow limitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology20121749349822142478

- BlamounAIBattyGNDeBariVARashidAOSheikhMKhanMAStatins may reduce episodes of exacerbation and the requirement for intubation in patients with COPD: evidence from a retrospective cohort studyInt J Clin Pract2008621373137818422598

- SoysethVBrekkePHSmithPOmlandTStatin use is associated with reduced mortality in COPDEur Respir J20072927928317050558

- LawesCMThornleySYoungRStatin use in COPD patients is associated with a reduction in mortality: a national cohort studyPrim Care Respir J201221354022218819