Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the top five major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Despite worldwide health care efforts, costs, and medical research, COPD figures demonstrate a continuously increasing tendency in mortality. This is contrary to other top causes of death, such as neoplasm, accidents, and cardiovascular disease. A major factor affecting COPD-related mortality is the acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD). Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity in individual patients. Despite the underestimation by the physicians and the patients themselves, AECOPD is a really devastating event during the course of the disease, similar to acute myocardial infarction in patients suffering from coronary heart disease. In this review, we focus on the evidence that supports the claim that AECOPD is the “stroke of the lungs”. AECOPD can be viewed as: a Semicolon or disease’s full-stop period, Triggering a catastrophic cascade, usually a Relapsing and Overwhelming event, acting as a Killer, needing Emergent treatment.

Keywords:

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwideCitation1 despite increased health care efforts, financial costs, and research concerning its early diagnosis and proper management. COPD epidemiology continues to display a steep increasing trend in mortality, contrary to the other leading causes of death like cancer and cardiovascular disease.Citation2 The most relevant event affecting COPD mortality is the acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), a catastrophic event during the clinical course of the disease.Citation3

The frequency and severity of AECOPD is the major modifier of the management and outcome of COPD. This was the reason that Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) current initiatives emphasized it even in its COPD definition.Citation3 The GOLD definition of AECOPD is characterized by clinical empiricism, but is too vague to be useful in the clinical interpretation of COPD patients developing acute exacerbations.

The fact is that COPD prevalence, which is on the rise in developing and developed countries, results in enlarged direct and indirect costs of COPD on the health care systems worldwide. According to several reports, in the US, direct costs have escalated from $18 billion in 2002 to $29.5 billion in 2010, consisting mainly of hospital expenses, whereas indirect costs account for 27%–61% of the total costs, with the higher estimates shown by studies focusing on working age populations.Citation4–Citation6 Average costs for individuals retiring early due to COPD have been estimated to be $316,000 per individual.Citation7 In Europe, a remarkable annual cost of €38.7 billion was caused by COPD.Citation8 Hospitalizations are the greatest contributor to total COPD costs, and account for up to 87% of the total COPD-related costs.Citation9 Exacerbations are the main cause of the hospital admissions and subsequently account for between 40% and 75% of COPD’s total health care costs, despite improvement in new maintenance medications.Citation10,Citation11 The health care systems worldwide need to endorse the health policies aiming at prevention and appropriate management of COPD exacerbations.

In this review, we focus on the evidence that supports the claim that AECOPD, especially when accompanied by respiratory failure and leads to hospitalization, is the “stroke of the lungs” leading to accelerated loss of lung function and contributes remarkably to increase in morbidity and mortality. We present an overview of the effects of an acute exacerbation in the disease’s clinical course, characterized by triggering a catastrophic cascade that is actually a killer, especially when it presents as a relapsed event.

Semicolon or disease’s full-stop period

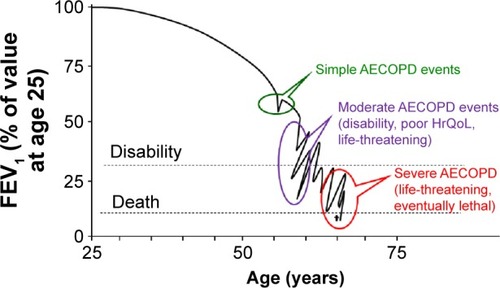

Contrary to the common perception that lung function decline is a gradual steady process that can be visualized by the Fletcher–Peto diagram,Citation12 evidence shows that lung function decline is not a constant, stable process. It is the accumulated result of mild losses during steady state and sharp losses, due to acute exacerbations, that accelerate as exacerbations become more frequent and more severe over time, during the disease’s natural course ().

Figure 1 Fletcher–Peto diagram modified: lung function decline is not a constant, stable process.

Abbreviations: AECOPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; HrQoL, health-related quality of life.

Even since the end of the 1970s, exacerbations have been implicated as a possible independent factor associated with lung function decline.Citation13 But only after large cohort studies were performed, the relationship between exacerbations and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) decline was established. The Lung Health Study reported that each additional exacerbation was associated with a greater annual decline of 7 mL.Citation14 The London COPD cohort study investigators showed a greater annual decline of 8 mL in frequent exacerbators, compared to non–exacerbation-prone patients.Citation15 Patients with higher rates of exacerbations showed more rapid lung function decline in the UPLIFT study also.Citation16 This exacerbation frequency–lung function decline relationship has also been reported in ex-smokers.Citation17

Part of this decline may be attributed to increased airway inflammation caused by exacerbations,Citation18 systemic inflammation,Citation19 and incomplete symptomatic and physiological resolution, as observed in a significant percentage of COPD patients after an acute exacerbation.Citation20 Exacerbations may contribute to as much as 25% of lung function decline.Citation21

If no further exacerbations occur in the following 6-month period, health status seems to recover to levels similar to those in patients with no exacerbations. But this is not a common rule.Citation22 In the SUPPORT study, a prospective cohort of 1,016 patients with an exacerbation of COPD and a PaCO2 of 50 mmHg or more were enrolled.Citation23 At 6 months, only 26% of the cohort was both alive and capable of reporting a good, very good, or excellent quality of life.Citation23

If recurrent events occur, they inhibit full recovery and accelerate health status deterioration.Citation24,Citation25 Exacerbations show seasonal distributionCitation26 and tend to cluster together in time, suggesting a high-risk period of 8 weeks for recurrent exacerbations after the initial exacerbation.Citation27 The European Respiratory Society (ERS) COPD audit survey revealed high 90-day readmission rates across Europe, reaching almost 40%.Citation28 The time period after an exacerbation is also a high-risk period for all-cause mortality.Citation29

Triggering a catastrophic cascade

There is a striking similarity in the catastrophic pathophysiologic cascade triggered by acute COPD exacerbations and acute myocardial infarctions (MIs) (). The latter, in the context of coronary heart disease (CHD), lead to more symptoms, recurrent events,Citation30 worsening of extraction fraction, lower ability for exercise, more frequent hospital admissions,Citation31 lower quality of life scores,Citation32 and increased mortality.Citation33 Acute exacerbations of COPD lead to more symptoms, lung function decline,Citation14,Citation15 lower exercise capacity,Citation34 higher hospitalization rates,Citation35,Citation36 lower quality of life,Citation37 as well as poorer prognosis.Citation38,Citation39

Table 1 Similarities in the catastrophic pathophysiologic cascade triggered by acute myocardial infarctions and acute COPD exacerbations

COPD and vascular diseases do not just share common risk factors like smoking and aging.Citation40 The crosstalk between COPD exacerbations and acute events of vascular diseases is impressive, only as COPD has been reported as a contributing factor for endothelial inflammation,Citation41,Citation42 it may induce arterial stiffness, aggravate atherosclerosis,Citation43 and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Reduced lung function correlates with a higher cardiovascular mortalityCitation44,Citation45 and the risk of ventricular arrhythmias.Citation46 A reduced FEV1 has been considered a prognostic marker for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality,Citation47 which may increase as much as 28% for every 10% decrement in FEV1 value.Citation48 In a study analyzing, over a 2-year period, 25,857 patients with COPD from the Health Improvement Network database, COPD exacerbation was associated with a significant increase in risk for MI during a 5-day postexacerbation period.Citation49 The presence of COPD is reported to worsen the long-term outcomes in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft.Citation50,Citation51 In a study of 81,191 MI patients, of whom 4,867 (6%) had a baseline COPD hospital discharge diagnosis, the COPD patients were reported to have a significantly higher 1-year mortality.Citation52

Relapsing event

Recurring acute events is no coincidence. Acute COPD exacerbations are among the strongest predisposing factors for future exacerbations, as recognized even in smaller cohort studies.Citation53 Our knowledge regarding AECOPD management was widely extended by large cohort studies like TORCH,Citation54 UPLIFT,Citation55 and ECLIPSE,Citation56 which illustrated that exacerbation frequency increases alongside disease severity. But the rate at which exacerbations occur highlights a distinct phenotype of patients, recognized by the ECLIPSE study, in moderate and severe COPD.Citation56 Besides disease progression, increased exacerbation frequency may be attributed to inadequate treatment, intrinsic factors like lower airway bacterial load,Citation57,Citation58 lower levels of physical activity,Citation59 or exposure to environmental triggers, especially viral or bacterial infections.Citation60 The frequent exacerbator, a distinct and well-described phenotype of the disease, tends to have reduced responses to treatment for acute exacerbations concerning inflammatory indices and quality of life,Citation61 and higher airway inflammation in the steady state and quicker elevation of systemic inflammation levels over time.Citation62 Acute vascular events such as MI tend to present a similar pattern of relapse.Citation30 In a study of 3,010 patients with first episode of MI, 30-day readmission rate after discharge was as high as 18.2%,Citation63 42.6% of which was associated with a new MI event, while COPD presence was also related to an increased risk of readmission.Citation63 The postinfarction period is a high risk period for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) as well as all-cause mortality.Citation64

Overwhelming

AECOPD is not considered just an acute event characterized by worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms; it presents an overwhelming situation leading to more frequent serious adverse events.

Patients participating in the UPLIFT studyCitation55 were observed over a 4-year period, and exacerbations or adverse events were recorded throughout the period in patients receiving the study drug. The researchers of the UPLIFT study examined in a later time point this large clinical trial database (5,992 COPD patients) to assess the relationship between exacerbations and the occurrence of nonrespiratory morbidity recorded as adverse events.Citation65 A total of 3,960 patients had an exacerbation and were analyzed. Non-lower Respiratory Serious Adverse Events’ (NRSAEs) incidence rates (IRs; per 100 patient-years) were recorded before and after the first exacerbation. Comparison of IR 30 days before and after an exacerbation showed significant changes (20.2 vs 65.2 with RR [95% confidence interval] =3.22 [2.40–4.33]). Similar IR changes were observed for the 180-day period (13.2 vs 31.0 with RR [95% confidence interval] =2.36 [1.93–2.87]). The top three common NRSAEs were cardiac, other respiratory conditions, and gastrointestinal. All NRSAEs including cardiac events were more frequent after the first exacerbation, irrespective of the cardiac comorbidity of the patient at baseline.

The combination of worsening respiratory symptoms and increased systemic events after exacerbations, particularly shortly after the event, has a dramatic impact in patients’ quality of life and feelings. This impact was studied by a qualitative interview-based study, which was conducted to gain an insight into patients’ comprehension and experience of COPD exacerbations and to explore their perspective on the burden of exacerbations.Citation66 Patients (n=125) with moderate-to-very severe COPD with two or more exacerbations during the previous year underwent a 1-hour face-to-face interview with a trained interviewer. Although commonly used by physicians, only 1.6% of patients understood the term “exacerbation”, preferring to use simpler terms such as “chest infection” or “crisis” instead. About two-thirds of patients stated that they were aware when an exacerbation was imminent and, in most cases, symptoms were consistent among exacerbations. Some patients (32.8%) did not report any recognizable warning signs. At the onset of an exacerbation, self-administering their medication was reported by 32.8% of the patients.

The majority of patients (64.8%) cited that exacerbations affected their mood, causing a variety of negative feelings such as anxiety, isolation, depression, irritability/bad temper, anger, and guilt. Overall, patients most commonly reported lack of energy, depression, and anxiety when describing their feelings about exacerbations. These effects seem to have adverse consequences in their personal and family relationships, leading to prevention of social activities and isolation. It is remarkable that physicians tended to underestimate the psychological impact of exacerbations, when compared to patient reports.

It is also remarkable that patients with coronary disease experienced the same feelings as COPD patients, as reported by The Heart and Soul Study.Citation67 Out of 1,024 participants, 201 (20%) had depressive symptoms. Depressive participants were more likely to report at least mild symptom burden (60% vs 33%), mild physical limitation (73% vs 40%), mildly diminished quality of life (67% vs 31%), and fair or poor overall health (66% vs 30%). Depressive symptoms were strongly related to greater physical limitation, greater symptom burden, worse quality of life, and worse overall health, when using multivariate analyses adjusting for cardiac function and other patient characteristics.

Based on the aforementioned data, depressive symptoms, after a heart attack, are strongly associated with patient-reported health status in patients with coronary disease, which is similar to the case of COPD patients after an acute exacerbation of the disease.

Killer

According to GOLD guidelines, exacerbations of COPD requiring hospitalization are associated with significant mortality.Citation3

In-hospital mortality of COPD patients admitted for a hypercapnic exacerbation with acidosis iŝ10%.Citation23,Citation68,Citation69 In the SUPPORT study,Citation23 as aforementioned, 1,016 patients were enrolled, who were admitted with an exacerbation of COPD and a PaCO2 of 50 mmHg or more. The 60-day, 180-day, 1-year, and 2-year mortality was high (20%, 33%, 43%, and 49%, respectively) and at 6 months, only 26% of the cohort was both alive and capable of reporting a satisfactory quality of life.

Similar results were reported in another study where 205 consecutive patients hospitalized with AECOPD were prospectively assessed and were followed up for 3 years.Citation68 In total, 17 patients (8.3%) died in hospital and the overall 6-month mortality rate was 24%, with 1-, 2-, and 3-year mortality rates of 33%, 39%, and 49%, respectively.Citation68

The 1-year mortality rates after an AECOPD seem to be affected by the presence of respiratory failure.Citation69 In a cohort of 171 patients, the mortality rate during hospitalization was 8%, going up to 23% after 1 year of follow-up.Citation69 Despite a comparable in-hospital mortality rate (6%), the 1-year mortality rate was reported to be significantly higher for patients admitted to the intensive care unit due to respiratory failure (35%).

The high rates of mortality after an AECOPD have been also reported in the ERS COPD audit survey.Citation28 The ERS COPD audit was a cross-sectional, multicenter study that analyzed the outcomes of COPD patients admitted to hospital with an exacerbation across Europe. Finally, 16,000 patients and 400 centers across 13 European countries were included in this project. Mortality among COPD patients discharged from hospital and within 90 days of the initial admission date was 6.1% (5.8% in males and 6.8% in females). The composite mortality rate (in-hospital plus 90 days follow-up period) was 11.1%.

Similarly, the incidence rates of sudden cardiac death and recurrent ischemic events post-MI were examined in a large cohort study.Citation70 Between 1979 and 1998, 2,277 MIs occurred (57% in men). After 3 years, the event-free survival rate was 94% for sudden cardiac death and 56% for recurrent ischemic events. Both outcomes were more frequent with older age and greater comorbidity.Citation70 As the authors concluded, in the community, recurrent ischemic events are frequent post-MI, while sudden cardiac death is less common. Thus, a COPD exacerbation is related to higher mortality rates than an MI in the general population.

Emergency

AECOPD is a severe medical condition demanding immediate action.Citation3 The initial management includes: assessment of medical history and clinical signs of severity, administration of supplemental oxygen therapy, increasing the dose or/and frequency of inhaled bronchodilators, and addition of oral or intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics (oral or intravenous) if signs of bacterial infection are present.Citation3

In cases of acute respiratory acidosis, noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) is considered. NIV has been shown to improve severity of breathlessness and acute respiratory acidosis and decrease the respiratory rate, work of breathing, complications such as ventilator-associated pneumonia, and the length of hospitalization.Citation3 More importantly, NIV decreases the intubation rates and mortality.Citation71,Citation72 If a patient is unable to tolerate NIV, or in case of NIV failure, invasive mechanical ventilation is mandated. Indications of initiating invasive mechanical ventilation include respiratory or cardiac arrest, respiratory pauses with loss of consciousness or gasping for air, massive aspiration, severe ventricular arrhythmias, severe hemodynamic instability, and persistent inability to remove respiratory secretions.Citation3 At all times of the management of an acute exacerbation, the medical stuff has to monitor the fluid balance and nutrition of the patient; subcutaneous heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin must be considered, and most importantly, associated conditions (eg, heart failure, arrhythmias) must be identified and treated.Citation3

When an acute exacerbation has to be managed, a serious problem is that the COPD patient is rarely only “COPD patient”. Comorbidities are frequent in COPD and 12 of them negatively influence survival.Citation73 For example, COPD and CHD share a common major risk factor, which is smoking. The coexistence has been reported as high as 30% or even higher in COPD patients.Citation74 In some studies of COPD patients’ medical records, the undiagnosed cases of CHD have reached 70%.Citation75 Also, AF and COPD are two common morbidities and often coexist.Citation76 The presence and severity of COPD are associated with increased risk for AF/atrial flutter and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. The prevalence of AF and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia among COPD patients has been reported to be as high as 23.3% and 13.0%, respectively.Citation77 Hypertension, diabetes and metabolic syndrome, cachexia, myopathy, mental disorders, osteoporosis, and chronic renal failure are also common comorbidities in COPD patients.Citation78 Finally, studies show that up to 94% of COPD patients have at least one comorbid disease and up to 46% have three or more.Citation79 Thus, during an AECOPD, the coexistence of comorbidities creates a “lethal cocktail” that has to be faced by the physicians.

Conclusion

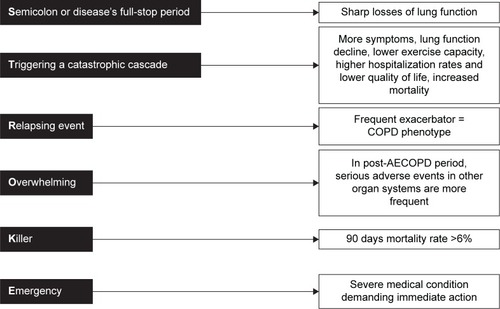

Despite the underestimation by the physicians and the patients themselves, AECOPD is a really catastrophic event in the natural course of the disease, similar to acute MI in patients suffering from CHD ().

AECOPD can be considered as the “stroke of the lungs” and it can be viewed as: a Semicolon or disease’s full-stop period, Triggering a catastrophic cascade, usually a Relapsing and Overwhelming event, acting as a Killer, needing Emergent treatment ().

Figure 2 AECOPD is the “stroke of the lungs”.

Acknowledging the pivotal role of AECOPD in progression of the disease is crucial in order to design and incorporate a multimodality preventive approach that focuses not only on prevention of exacerbations, but also on the comorbidities that can transform even a minor respiratory exacerbation into a potentially lethal event.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Resp Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- WHOChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)GenevaWorld Health Organization2011 Available from: www.who.int/respiratory/copdAccessed January 3, 2016

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease revised2014 Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/management/en/Accessed January 3, 2016

- OrnekTTorMAltınRClinical factors affecting the direct cost of patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Med Sci20129428529022701335

- PatelJGNagarSPDalalAAIndirect costs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review of the economic burden on employers and individuals in the United StatesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014928930024672234

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteMorbidity and Mortality 2009: Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung and Blood DiseasesBethesdaNational Institutes of Health2009

- FletcherMJUptonJTaylor-FishwickJCOPD uncovered: an international survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] on a working age populationBMC Public Health20111161221806798

- HalpinDMMiravitllesMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the disease and its burden to societyProc Am Thorac Soc20063761962316963544

- DarnellKDwivediAKWengZPanosRJDisproportionate utilization of healthcare resources among veterans with COPD: a retrospective analysis of factors associated with COPD healthcare costCost Eff Resour Alloc2013111323763761

- HillemanDDewanNMaleskerMFriedmanMPharmacoeconomic evaluation of COPDChest200011851278128511083675

- TeoWTanWSChongWEconomic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology201217112012621954985

- FletcherECPetoRThe natural history of chronic airflow obstructionBr Med J1977116451648871704

- KannerRERenzettiADJrKlauberMRSmithCBGoldenCAVariables associated with changes in spirometry in patients with obstructive lung diseasesAm J Med1979674450313706

- KannerREAnthonisenNRConnettJELower respiratory illnesses promote FEV1 decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild obstructive pulmonary disease: Results from the lung health studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116435836411500333

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTARBhowmikAWedzichaJARelationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax20025784784512324669

- HalpinDMDecramerMCelliBKestenSLiuDTashkinDPExacerbation frequency and course of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012765366123055714

- MakrisDMoschandreasJDamianakiAExacerbations and lung function decline in COPD: new insights in current and ex-smokersRespir Med20071011305131217112715

- BhowmikASeemungalTASapsfordRJWedzichaJARelation of sputum inflammatory markers to symptoms and lung function changes in COPD exacerbationsThorax20005511412010639527

- GroenewegenKHDentenerMAWoutersEFLongitudinal follow-up of systemic inflammation after acute exacerbations of COPDRespir Med20071012409241517644367

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCBhowmikAJeffriesDJWedzichaJATime course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001611608161310806163

- WedzichaJADonaldsonGCExacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Care2003481204121314651761

- BourbeauJFordGZackonHPinskyNLeeJRubertoGImpact on patients’ health status following early identification of a COPD exacerbationEur Respir J20073090791317715163

- ConnorsAFDawsonNVThomasCOutcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The SUPPORT investigators (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments)Am J Respir Crit Care1996154959967

- SpencerSJonesPWTime course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitisThorax200358847852

- SpencerSCalverleyPMBurgePSJonesPWImpact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPDEur Respir J20042369870215176682

- DonaldsonGCWedzichaJAThe causes and consequences of seasonal variation in COPD exacerbationsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491101111025336941

- HurstJDonaldsonGCQuintJGoldringJBaghai-RavaryRWedzichaJTemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200917936937419074596

- CrinionSCotterOKennedyBCOPD exacerbations – a comparison of Irish data with European data from the ERS COPD auditIr Med J2013106270272

- GroenewegenKHScholsAMWoutersEFMortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPDChest200312445946712907529

- AdabagASTherneauTMGershBJWestonSARogerVLSudden death after myocardial infarctionJAMA20083002022202918984889

- ChaudhrySIKhanRFChenJNational trends in recurrent AMI hospitalizations 1 year after acute myocardial infarction in Medicare beneficiaries: 1999–2010J Am Heart Assoc201435e00119725249298

- HawkesALPatraoTAWareRAthertonJJTaylorCBOldenburgBFPredictors of physical and mental health-related quality of life outcomes among myocardial infarction patientsBMC Cardiovasc Disord2013136924020831

- ZamanSKovoorPSudden cardiac death early after myocardial infarction: pathogenesis, risk stratification, and primary preventionCirculation2014129232426243524914016

- DonaldsonGCWilkinsonTMHurstJRPereraWRWedzichaJAExacerbations and time spent outdoors in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200517144645215579723

- DewanNARafiqueSKanwarBAcute exacerbations of COPD. Factors associated with poor treatment outcomesChest200011766267110712989

- Garcia-AymerichJMonsóEMarradesRMRisk factors for hospitalization for a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. EFRAM studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med20011641002100711587986

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCPaulEABestallJCJeffriesDJWedzichaJAEffect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med1998157141814229603117

- Soler-CataluñaJJMartínez-GarcíaMARomán SánchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- Domingo-SalvanyALamarcaRFerrerMHealth-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216668068512204865

- DollRPetoRWheatleyKGrayRSutherlandIMortality in relation to smoking: 40 years’ observations on male British doctorsBMJ19943099019117755693

- TakahashiTKobayashiSFujinoNIncreased circulating endothelial microparticles in COPD exacerbation susceptibilityThorax2012671067107422843558

- TakahashiTKobayashiSFujinoNAnnual FEV1 changes and numbers of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with COPD: a prospective studyBMJ Open20144e004571

- McAllisterDAMaclayJDMillsNLArterial stiffness is independently associated with emphysema severity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20071761208121417885263

- LöfdahlCGCOPD and co-morbidities, with special emphasis on cardiovascular conditionsClin Respir J20082Suppl 1596320298351

- SinDDWuLManSFThe relationship between reduced lung function and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based study and a systematic review of the literatureChest20051271952195915947307

- EngströmGWollmerPHedbladBJuul-MöllerSValindSJanzonLOccurrence and prognostic significance of ventricular arrhythmia is related to pulmonary function: a study from ‘men born in 1914,’ Malmö, SwedenCirculation20011033086309111425773

- ManninoDMWattGHoleDThe natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J20062762764316507865

- QuintJKHerrettEBhaskaranKEffect of beta blockers on mortality after myocardial infarction in adults with COPD: population based cohort study of UK electronic healthcare recordsBMJ2013347f665024270505

- DonaldsonGCHurstJRSmithCJHubbardRBWedzichaJAIncreased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke following exacerbation of COPDChest20101371091109720022970

- SelvarajCLGurmHSGuptaREllisSGBhattDLChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a predictor of mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventionAm J Cardiol20059675675916169353

- LeavittBJRossCSSpenceBLong-term survival of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing coronary artery bypass surgeryCirculation20061141 SupplI430I43416820614

- AndellPKoulSMartinssonAImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on morbidity and mortality after myocardial infarctionOpen Heart201411e00000225332773

- HisebøGRBakkePSAanerudMPredictors of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – Results from the Bergen COPD cohort studyPLoS One2014910e10972125279458

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med200735677578917314337

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20083591543155418836213

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20103631128113820843247

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTAPatelISLloyd-OwenSJWilkinsonTMWedzichaJALongitudinal changes in the nature, severity and frequency of COPD exacerbationsEur Respir J20032293193614680081

- PatelISSeemungalTARWiksMLloyd-OwenSJDonaldsonGCWedzichaJARelationship between bacterial colonization and the frequency, character and severity of COPD exacerbationsThorax20025775976412200518

- EstebanCArosteguiIAbustoMInfluence of changes in physical activity on frequency of hospitalization in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology20141933033824483954

- SeemungalTHarper-OwenRBhowmikARespiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20011641618162311719299

- ChangCYaoWTime course of inflammation resolution in patients with frequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Sci Monit20142031132024569299

- DonaldsonGSSeemungalTAPatelISAirway and systemic inflammation and decline of lung function in patients with COPDChest20051281995200516236847

- DunlaySMWestonSAKillianJMBellMRJaffeASRogerVLThirty-day rehospitalizations after acute myocardial infarction: a cohort studyAnn Intern Med20121571111822751756

- BangCNGislasonGHGreveAMNew-onset atrial fibrillation is associated with cardiovascular events leading to death in a first time myocardial infarction population of 89,703 patients with long-term follow-up: a nationwide studyJ Am Heart Assoc201431e00038224449803

- HalpinDMDecramerMCelliBKestenSLeimerITashkinDPRisk of nonlower respiratory serious adverse events following COPD exacerbations in the 4-year UPLIFT® trialLung201118926126821678045

- KesslerRStahlEVogelmeierCPatient understanding, detection, and experience of COPD exacerbations: an observational, interview-based studyChest200613013314216840393

- RuoBRumsfeldJSHlatkyMALiuHBrownerWSWhooleyMADepressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: The heart and soul studyJAMA2003290221522112851276

- GunenHHacievliyagilSSKosarFFactors affecting survival of hospitalised patients with COPDEur Respir J200526223424116055870

- GroenewegenKHScholsAMWoutersEFMortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPDChest2003124245946712907529

- JokhadarMJacobsenSJReederGSWestonSARogerVLSudden death and recurrent ischemic events after myocardial infarction in the communityAm J Epidemiol20041591040104615155288

- BrochardLManceboJWysockiMNoninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med1995333138178227651472

- BottJCarrollMPConwayJHRandomised controlled trial of nasal ventilation in acute ventilatory failure due to chronic obstructive airways diseaseLancet19933418860155515578099639

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- SinDDManSFChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortalityProc Am Thorac Soc20052181116113462

- BrekkePHOmlandTSmithPSøysethVUnderdiagnosis of myocardial infarction in COPD – Cardiac Infarction Injury Score (CIIS) in patients hospitalised for COPD exacerbationRespir Med200810291243124718595681

- HuangBYangYZhuJClinical characteristics and prognostic significance of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with atrial fibrillation: Results from a multicenter atrial fibrillation registry studyJ Am Med Dir Assoc201415857658124894999

- KonecnyTParkJYSomersKRRelation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to atrial and ventricular arrhythmiasAm J Cardiol2014114227227724878126

- TsiligianniIGKosmasEVan der MolenTTzanakisNManaging comorbidity in COPD: A difficult taskCurr Drug Targets201314215817623256716

- FumagalliGFabianiFForteSINDACO project: a pilot study on incidence of comorbidities in COPD patients referred to pneumology unitsMultidiscip Respir Med2013812823551874