Abstract

Background

Blood eosinophil counts have been documented as a good biomarker for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy. However, the effectiveness and safety of prescribing high or medium dose of ICS for patients with different eosinophil counts are unknown.

Methods

A post hoc analysis of a previous prospective randomized study was performed for COPD patients using higher dose (HD: Fluticasone 1,000 μg/day) or medium dose (MD: Fluticasone 500 μg/day) of ICS combined with Salmeterol (100 μg/day). Patients were classified into two groups: those with high eosinophil counts (HE ≥3%) and those with low eosinophil counts (LE <3%). Lung function was evaluated with forced expiratory volume in 1 second, forced vital capacity, and COPD assessment test. Frequencies of acute exacerbation and pneumonia were also measured.

Results

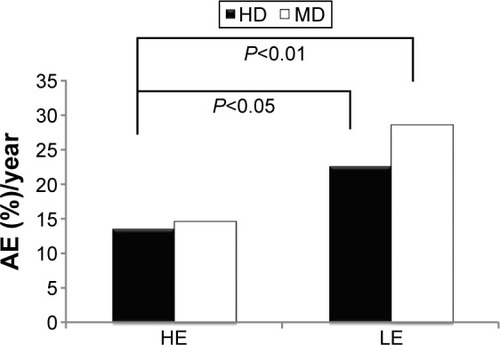

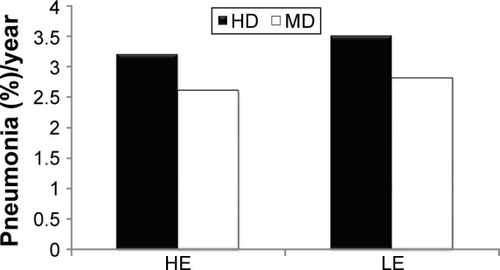

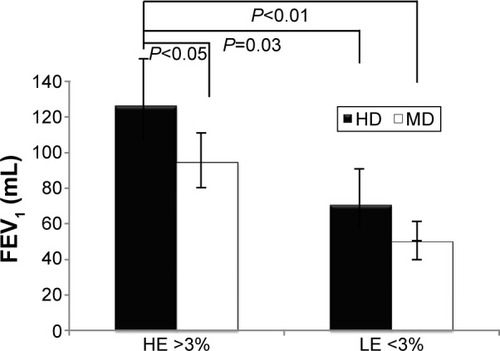

Two hundred and forty-eight patients were studied and classified into higher eosinophil (HE) (n=85, 34.3%) and lower eosinophil (LE) groups (n=163, 65.7%). The levels of forced expiratory volume in 1 second were significantly increased in patients of HE group treated with HD therapy, compared with the other groups (HE/HD: 125.9±27.2 mL vs HE/MD: 94.3±23.7 mL, vs LE/HD: 70.4±20.5 mL, vs LE/MD: 49.8±16.7 mL; P<0.05) at the end of the study. Quality of life (COPD assessment test) markedly improved in HE/HD group than in MD/LE group (HE/HD: 9±5 vs LE/MD: 16±7, P=0.02). The frequency of acute exacerbation was more decreased in HE/HD group patients, compared with that in LE/MD group (HE/HD: 13.5% vs LE/MD: 28.7%, P<0.01). Pneumonia incidence was similar in the treatment groups (HE/HD: 3.2%, HE/MD: 2.6%, LE/HD: 3.5%, LE/MD 2.8%; P=0.38).

Conclusion

The study results support using blood eosinophil counts as a biomarker of ICS response and show the benefits of greater improvement of lung function, quality of life, and decreased exacerbation frequency in COPD patients with blood eosinophil counts higher than 3%, especially treated with higher dose of ICS.

Introduction

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) reduce the risk of moderate and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) acute exacerbation (AE) in patients with moderate to very severe lung function defect and a history of frequent exacerbation.Citation1–Citation5 However, treatment benefits are slight and are offset by an increased risk of adverse effects, especially pneumonia.Citation6 Therefore, identification of a simple biomarker associated with treatment response would be necessary. Airway eosinophil inflammation, a significant feature of asthma, is recognized as an inflammatory endotype in COPD.Citation7–Citation9 COPD with eosinophilic inflammation, defined as sputum eosinophils ≥3%, is reported to be found in up to 28% of cases during AEs,Citation10 and interestingly, it is seen in approximately 34%Citation11 (or 38%Citation12) of COPD patients in periods of stable disease. Airway eosinophilic inflammation is a reliable predictor of benefit from inhaled and oral corticosteroid treatment in patients with COPD.Citation12–Citation15

The measurement and evaluation of airway eosinophilic inflammation usually require the assessment of induced sputum examination.Citation8 Sputum induction is a direct and reliable method of evaluating airway inflammation characteristics. However, there exist a number of limitations.Citation16,Citation17 In addition to being unsuitable for point-of-care testing, it requires more experience to differentiate inflammatory counts and may not be always precise and successful (failure rate near 30%).Citation16,Citation17 Due to these reasons, alternative tools for minimally invasive and easily applicable diagnostic methods that can detect sputum eosinophilia in asthma and COPD have been emphasized.Citation10,Citation11,Citation18–Citation21 The use of peripheral serum cell counts may be a potential alternative and attracting tool due to its ease of application in our daily practice. The association of sputum eosinophilia and blood eosinophils in asthma patients has been demonstrated, with promising results.Citation21–Citation24 In COPD patients, however, very few studies have mentioned this blood eosinophils application tool, particularly in clinical stability for these patients. A recent study in 20 COPD patients and 21 healthy controls has reported the relationship between bronchial and blood eosinophil counts.Citation25 Studies have also demonstrated that the blood eosinophil counts may serve as a biomarker of corticosteroid treatment effectiveness in exacerbatingCitation26 and stableCitation27,Citation28 COPD patients. The clinical characteristics of stable COPD patients with higher levels of blood eosinophils (≥2%) and their series changes occurring during a 3-year follow-up have also been elucidated.Citation9 Therefore, blood eosinophil counts seem to be a reliable biomarker to predict exacerbation status and ICS-treated responsiveness in COPD patients.

Our previous study had documented that COPD patients treated with higher ICS dose have more clinical effectiveness compared to those treated with medium ICS dose.Citation29 However, the benefits and safety of high or medium dose for patients with different blood eosinophil counts are unknown. The aim of the study was to compare the treatment effectiveness of different ICS doses in COPD patients with different blood eosinophilic counts.

Methods

Study design

Ethical approval was received from the institutional review board/ethics committee of Far Eastern Memorial hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. This study was a post hoc analysis of our previous studyCitation29 in which the patients were nonblinded and randomized 1:1 to one of two treatment groups: high-dose (HD) and medium-dose (MD) ICS groups. From the previous drug therapy, these COPD patients were randomized to and prescribed one of the two treatment doses, which were higher dosage (HD) and medium dosage (MD) of ICS. The definition of higher dose of ICS was Fluticasone 1,000 μg/day and medium dose of ICS was Fluticasone 500 μg/day. Both treatment regimens were combined with Salmeterol 100 μg/day and were administered by a hydrofluoroalkane pressurized metered-dose inhaler with a space device (GlaxoSmithKline plc, London, UK).

Characteristics of the participants

The diagnoses of these participants were according to the following criteria: history, physical examination, chest radiograph findings, and spirometric data. Inclusion criteria for COPD were as follows: chronic airway signs and symptoms such as cough with sputum, breathlessness, wheezing, and confirmed chronic airway obstruction, which was defined as 1) forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) <70% and 2) FEV1 <80% of the predicted value by spirometric data, and FEV1 reversibility after inhalation of 200 μg salbutamol of <12% of prebronchodilator FEV1. Men and women (aged over 40 years) with COPD diagnosed for over 6 months prior to screening were enrolled in the study. Smoking history with at least 10 pack-years should be noted.

Patients with the following conditions were excluded: AE of life-threatening COPD within the past year, hospitalization or emergency department visit for COPD in the 4 weeks prior to screening period, systemic corticosteroid used in the month before screening, a history of nonsmoking or smoking an equivalent to <10 pack-years, significant asthma diagnosis with airway reversible responsibility, active pulmonary tuberculosis disease, and clinically significant respiratory tract infection in the 4 weeks before screening. Current use of medications that would have an effect on bronchospasm and/or lung function was also a criterion for exclusion.

Study protocol

For this post hoc analysis of our randomized study, patients were classified into two groups according to their blood eosinophil counts: high eosinophil group with ≥3% eosinophil count (HE) and low eosinophil group with <3% eosinophil count (LE). The cutoff point of 3% eosinophil count was the reference, and therefore, sputum eosinophil counts over 3% will be of greater benefit with steroid therapy.Citation13 Therefore, patients were divided into having one of the four conditions, HE/HD, HE/MD, LE/HD, and LE/MD, respectively, according to their blood eosinophil counts (HE, LE) and ICS doses (HD, MD). The assessment parameters included lung function tests by spirometry (FEV1 and FVC) and symptom scores using COPD assessment test (CAT) tool.Citation30 Besides, the frequency of AE (COPD deterioration resulting in emergency treatment, hospitalization, or treatment with additional systemic steroid or antibiotic agents) was also measured. Safety issues were also surveyed, such as pneumonia incidence.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were compared using chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared by Student’s t-test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Fisher’s exact test (qualitative data) or analysis of variance (quantitative data) was performed to test the homogeneity of the treatment groups. A Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to help determine if the model fit to the data well. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 9.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

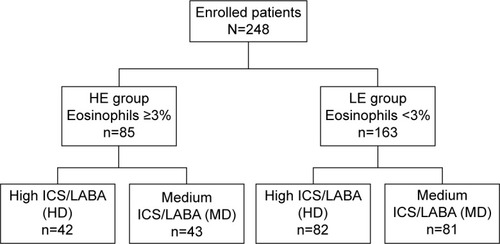

In the post hoc analysis, 248 patients were studied and classified as follows: 85 patients (34.3%) with high eosinophil counts (HE group, ≥3%) and 163 patients (65.7%) with low eosinophil counts (LE group, <3%) (). The demographics and COPD characteristics of patients in the HE and LE groups are summarized in . Most patients (84.9%) were male, and the average lung function was classified based on the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease III status (50.3% of predicted in the HE group and 52.5% of predicted in the LE group). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to treatment with higher ICS or medium ICS doses (P=0.39). Besides, regarding the lung function parameter with positive bronchodilator test responsiveness, there was no statistically significant difference between patients with high eosinophil counts and low counts (HE: 22.2% vs LE: 14.5%, P=0.08). However, there was higher AE frequency in the previous 1 year in HE patients compared with LE patients (HE: 27.1% vs LE: 7.4%, P<0.01).

Table 1 Baseline demographic characteristics of the study subjects with COPD

Figure 1 A flow chart for the number of subjects.

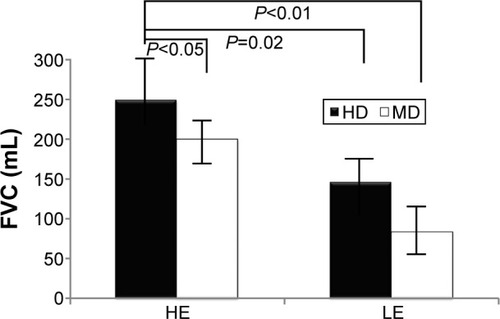

Analysis of the pulmonary function status with FEV1 and FVC revealed that patients showed improvements in lung function across both treatment groups during the study. The improved FEV1 levels among these patients were as follows: HE/HD: 125.9±27.2 mL versus HE/MD: 94.2±23.7 (P<0.05), versus LE/HD: 70.4±20.5 (P=0.03), and versus LE/MD: 49.8±16.7 (P<0.01). The levels of FVC were as follows: HE/HD: 248.4±51.3 mL versus HE/MD: 198.6±48.1 (P<0.05), versus LE/HD: 145.2±47.5 (P=0.02), and versus LE/MD: 82.6±44.3 (P<0.01). There was more significant lung function improvement in HE/HD patients when compared to that in patients of other groups ( and ). Patients receiving higher doses of Fluticasone showed greater efficacy in improvement of lung function, especially the patients also having high eosinophil counts.

Figure 2 Lung function improvement with FEV1 in HE and LE patients using HD and MD therapy.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; HD, high dose; HE, higher eosinophil count; LE, lower eosinophil count; MD, medium dose.

Figure 3 Lung function improvement with FVC in HE and LE patients using HD and MD therapy.

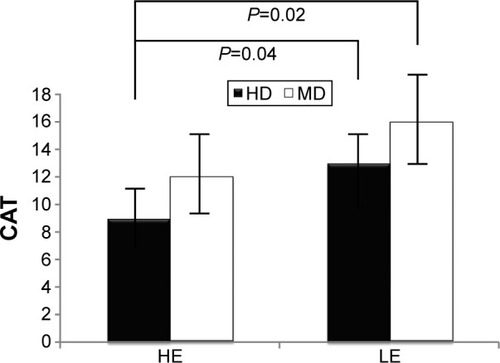

Patient-assessed COPD symptoms scores with CAT questionnaire decreased in both HE and LE groups, with a statistically significant difference found in favor of the patients treated in the HD group. The CAT scores were as follows: HE/HD: 9±5, HE/MD: 12±6, LE/HD: 13±5, and LE/MD: 16±7 throughout the study (). There was a trend of a higher quality of life among the patients who received continuous treatment with higher dose of ICS, especially in patients with accompanying high eosinophil counts, and statistically more significant difference in CAT scores among patients treated with medium ICS dose, even in those with high eosinophil counts (LE/HD). Average changes from baseline in the mean scores of CAT decrease also showed significant differences between HE patients and LE patients (8±3 vs 4±2, P=0.04) at the end of study, irrespective of whether the patients were treated with HD or MD therapy. There was greater benefit and more treatment response, especially in HE patients using ICS therapy.

Figure 4 Quality of life improvement with CAT scores in HE and LE patients using HD and MD therapy.

Also, the frequency of AE detection showed a significant difference in the patients of all four groups. The percentage of AE after ICS/long-acting beta-agonist treatment was HE/HD: 0.135, HE/MD: 0.147, LE/MD: 0.226, and LE/MD: 0.287 per person-year, respectively (). There was a significant difference and reduction in the percentage of AE in HE patients treated with HD, compared with other patients. None of the patients suffered from life-threatening AE. Meanwhile, there was no obvious difference in the incidence of pneumonia in these groups (HE/HD: 3.2%, HE/MD: 2.6%, LE/HD: 3.5%, LE/MD 2.8%; P=0.38) (). Other side effects such as hoarseness or oral candidiasis were similar among the patients in the four groups (HE/HD: 6.3%, HE/MD: 8.8%, LE/HD: 4.9%, LE/MD 9.2%; P=0.38).

Discussion

Our post hoc analysis demonstrated that the responsiveness was greater in lung function, quality of life, and decreased frequency of AE among COPD patients with high blood eosinophil count (≥3%) undergoing ICS treatment, especially in those on high-dose ICS therapy. The results were similar to other studiesCitation26–Citation28 in which greater effectiveness was noticed in treating high eosinophil counts with ICS. However, this is the first study to compare the benefits shown by high and medium ICS dose in COPD patients with high eosinophil count. Results of this study showed greater improvement from treatment with high ICS dose (Fluticasone 1,000 μg/day) than with medium ICS dose (Fluticasone 500 μg/day). Therefore, it is helpful to select the most appropriate treatments for individual patients and the blood eosinophil count has greater potential as a biomarker to improve decision making in COPD treatment.

Blood eosinophil count, a promptly available and easy-to-interpret measure, is probably a suitable tool as a biomarker in clinical practice to identify which COPD patients are most likely to benefit from the treatment efficacy of ICS. Our study revealed that there were higher exacerbation and hospitalization rates in patients with high eosinophil counts than in those with low eosinophil counts. Our result is similar to a recent report in which increased blood eosinophil levels above 0.34×109 cells/L were associated with a 1.76-fold increased risk of severe exacerbations.Citation31 Therefore, it may have immediate clinical implications as there are ongoing more complex inflammation processes, such as asthma pathogenesis, in the airway in patients with high eosinophil counts and the benefits were greater with the use of ICS treatment in patients with extreme higher eosinophil countsCitation27,Citation28 or with the use of high ICS dose to reduce antiallergic inflammation in these patients. A recent study,Citation32 however, reported that eosinopenia is a marker of poor outcome in COPD AE. It is important to clarify the true impact of the role of and the inflammation mechanism of eosinophils in patients with COPD.

The threshold for high eosinophil counts in COPD patients was not confirmed. Several studiesCitation26,Citation27,Citation33 had used 2% as the cutoff for the blood eosinophil level and documented that for patients with over 2% eosinophils, ICS combined with long-acting beta-agonist was associated with significant reduction in exacerbation rates versus Tiotropium (INSPIRE studyCitation34) or placebo (TRISTAN study).Citation35 Stratification by blood eosinophil level ≥3% versus <3% showed similar trends for TRISTAN. In the Foster 48-Week Trial to Reduce Exacerbation in COPD (FORWARD) study,Citation28 the stratified method involved total eosinophil counts, not the percentage. In our study, the threshold of 3% eosinophil level had shown significant difference in previous AE rate and a good response to high-dose therapy of ICS. The definition using 3% level in blood was based on the sputum cutoff levelCitation10–Citation12 in our study. It was found that the 3% cutoff level was associated with increased exacerbation risk than the 2% threshold level. Also, the clinical effectiveness with ICS was greater in patients with ≥3% than in those with <3%, but there was no significant difference if the threshold level was 2%. It should be further elucidated and studied as to which classifications of eosinophil levels are beneficial to the treatment guide.

A recent study had mentioned that patients with higher sputum eosinophils can predict more bronchial hyper-responsiveness (BHR) than the patients without BHR, and those with sputum eosinophils ≥3% had more frequent exacerbations in the previous year and higher symptom scores than the patients with sputum eosinophils <3%.Citation36 Sputum eosinophil count is known to be the most reliable predictor of responsiveness to ICS in COPD. However, there was no association between BHR and blood eosinophil percentage in our study, which is similar to another report.Citation37 The different sites of eosinophil counts may represent variable clinical characteristics. This phenomenon is like that reported in a recent study on uncontrolled asthma patients, of whom one third exhibited inconsistency between sputum and blood eosinophils.Citation38 There are some studies that confirm the concordance or discordance between sputum and blood eosinophils in patients with COPD. It should be further elucidated whether sputum eosinophil levels are in concordance with blood eosinophil counts or not, and airway eosinophil inflammation is compatible or not with systemic eosinophil inflammation in COPD.

Possible mechanisms for the inconsistency in blood and sputum eosinophils may consider the imbalance between the production by allergy and the subsequent clearance of eosinophils by airway macrophagesCitation39 and various stimulants in the inflammatory process of eosinophil recruitment into the airways.Citation38 The cause for only a small group of the COPD patients exhibiting higher blood eosinophils may be that it may be a response to the association of several kinds of biological mechanisms underlying eosinophilic inflammation in the pathogenesis (endotypes) and clinical characteristics (phenotype) of COPD.Citation40 Similar to the pathogenesis of asthma, stimulation and subsequent production of T helper (Th)2 cytokines may be responsible for eosinophilic inflammation in COPD subgroup.Citation40 However, it has also been reported that the coexisting eosinophilic inflammation in the airway of COPD patients is not due to elevated levels of Th2 cytokines responsiveness.Citation41 This may result from the non-Th2 eosinophilic inflammation in COPD, which is induced by the epithelial innate lymphoid cell type 2 pathways, and innate lymphoid cell type 2 has been documented the relationship of pathogenesis in severe nonallergic eosinophilic asthma.Citation42 Therefore, further studies should be performed in order to elucidate the pathogenesis involved in the association between different endotypes of eosinophil inflammation and COPD phenotypes.

Based on these inflammatory mechanisms, the role of ICS in suppressing eosinophilic inflammation is rational and essential. More importantly, there was more clinical effectiveness when HE patients were treated with ICS therapy, especially with a high ICS dose. There is still a controversy regarding the benefits and risks of ICS therapy in COPD patients. Our current and previous findings show that high ICS doses have greater clinical benefits in lung function improvement, improvement of quality of life, and reduction of AE, especially in the HE subset of COPD patients. The side effects, especially the incidence of pneumonia, did not increase in patients on high ICS therapy. Therefore, our results provide a reliable and effective strategy of prescribing high ICS therapy in COPD patients with high eosinophil count.

Limitations

The major limitation and weakness of the study is the post hoc analysis nature of the analyses, although the rationale for the study was based on previous findings. This survey is from our randomized controlled trial and appropriate analyses were put in place to control for confounding factors. Indeed, the designed parameters and factors for this survey are not the primary endpoints originally. The second limitation is the difficultly to assess blood eosinophilia as the only marker for measurement of ICS efficacy; also, we chose the cutoff point ≥3% to divide the groups, based on a previous study performed on sputum eosinophilia. There is no clear data to support that blood eosinophilia reflects sputum eosinophilia in patients with COPD. The strong basis to test the value of blood eosinophils as a marker to ICS treatment and comparison between the treatment effectiveness of high and medium dose of ICS prompted us to do this elucidation. Further prospective studies should be carried out with large sample sizes to highlight the usefulness and reliability of eosinophil counts as a biomarker in COPD patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, COPD patients with high eosinophils (≥3%) treated with high doses of ICS had improved lung function status, decreased exacerbation frequency, and showed greater relief from symptoms in comparison to those using medium doses of ICS and to other low-eosinophil (<3%) subgroups. Besides, no significant increase in the incidence of pneumonia development, especially on using high doses of ICS, was noticed. The study was the first study to compare the effectiveness of medium and high ICS doses in treatment of COPD with different eosinophil counts and provide an applicable dose for anti-inflammation response in COPD.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, on May 13–18, 2016, as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in American Thoracic Society International Conference Abstracts, C103. Eosinophils in COPD and the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome: sorting through the chaos of ACOS, 2016, pp. A6243. This study was supported by a grant from the Far Eastern Memorial Hospital (FEMH 2016-D-011).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FergusonGTAnzuetoAFeiREmmettAKnobilKKalbergCEffect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/25 microg) or salmeterol (50 microg) on COPD exacerbationRespir Med200810281099110818614347

- DransfieldMTBourbeauJJonesPWOnce-daily inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol versus vilanterol only for prevention of exacerbation of COPD: two replicate double-blind, parallel-group, randomized controlled trialLancet Respir Med20131321022324429127

- SzafranskiWWCukierARamirezAEfficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J2003211748112570112

- SharafkhanehASouthardJGGoldmanMUryniakTMartinUJEffect of budesonide/formoterol pMDI on COPD exacerbation: a double-blind, randomized studyRespir Med2012106225726822033040

- AgarwaiRAggarwaiANGuptaDJindalSKInhaled corticosteroids vs placebo for preventing COPD exacerbations: a systemic review and metaregression of randomized controlled trialsChest2010137231832519783669

- SuissaSNumber needed to treat in COPD: exacerbations versus pneumoniasThorax201368954054323125170

- SahaSBrightlingCEEosinophilic airway inflammation in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis200611394718046901

- BrightlingCEClinical applications of induced sputumChest200612951344134816685028

- SinghDKolsumUBringtlingCELocantoreNAgustiATsl-SingerRECLIPSE invertigatorsEosinophilic inflammation in COPD: prevalence and clinical characteristicsEur Respir J20144461697170025323230

- BafadhelMMckennaSTerrySAcute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkersAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184666267121680942

- McDonaldVMHigginsIWoodLGGibsonPGMultidimensional assessment and tailored interventions for COPD: respiratory utopia or common sense?Thorax201368769169423503624

- LeighRPizzichiniMMMorrisMMMaltaisFHargreaveFEPizzichiniEStable COPD: predicting benefits from high-dose inhaled corticosteroid treatmentEur Respir J200627596497116446316

- BrightlingCEMonteiroWWardRSputum eosinophilia and short-term response to prednisolone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trialLancet200035592401480148510801167

- BrightlingCEMckennaSHargadonBSputum eosinophilia and the short term response to inhaled mometasone in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax200560319319815741434

- PizzichiniEPizzichiniMMGibsonPSputum eosinophilia predicts benefit from prednisolone in smokers with chronic obstructive bronchitisAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981585 Pt 1151115179817701

- PavordIDBafadhelMExhaled nitric oxide and blood eosinophilia: independent markers of preventable riskJ Allergy Clin Immunol2013132482882924001802

- BainesKJPavordIDGibsonPGThe role of biomarkers in the management of airway diseaseInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201418111264126825299856

- PavordIDGibsonPGInflammometry: the current state of playThorax201267319119222344396

- YapEChuaWMJayaramLZengIVandalACGarrettJCan we predict sputum eosinophilia from clinical assessment in patients referred to an adult asthma clinic?Intern Med J2013431465221790924

- KorevaarDAWeaterhofGAWangJDiagnostic accuracy of minimally invasive markers for detection of airway eosinophilia in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet Respir Med20153429030025801413

- WesterhofGAKorevaarDAAmelinkMBiomarkers to identify sputum eosinophilia in different adult asthma phenotypesEur Respir J201546368869626113672

- ZhangXYSimpsonJLPowellHFull blood count parameters for the detection of asthma inflammatory phenotypesClin Exp Allergy20144491137114524849076

- FowlerSJTavernierGNivenRHigh blood eosinophil counts predict sputum eosinophilia in patients with severe asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2015135382282425445828

- WagenerAHde NijsSBLutterRExternal validation of blood eosinophils in asthmaThorax201570211512025422384

- EltboliOMistryVBarkerBBrightlingCERelationship between blood and bronchial submucosal eosinophilia and reticular basement membrane thickening in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology201520466767025645275

- BafadhelMMckennaSTerrySBlood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121861485522447964

- PascoeSLocantoreNDransfieldMTBarnesNCPavordIDBlood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone foroate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trialsLancet Respir Med20153643544225878028

- SiddiquiSHGuasconiAVestboJBlood eosinophils: a biomarker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015192452352526051430

- ChengSLSuKCWangHCPerngDWYangPCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with inhaled medium- or high-dose corticosteroids: a prospective and randomized study focusing on clinical efficacy and the risk of pneumoniaDrug Des Devel Ther20148601607

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD assessment testEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- Vedel-KroghSNielsenSFLangePVestboJNordestgaardBGBlood eosinophils and exacerbations in COPD: the Copenhagen general population studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2016193996597426641631

- Rahimi-RadMHAsgariBHosseinzadehNEishiAEosinopenia as a marker of outcome in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMaedica(Buchar)2015101101326225143

- PavordIDLettisSLocantoreNBlood eosinophils and inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β-2 agonist efficacy in COPDThorax201671211812526585525

- WedzichaJACalverleyPMSeemungalTAHaganGAnsariZStockleyRAThe INSPIRE investigatorsThe prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromideAm J Respir Crit Care Med20081771192617916806

- CalverleyPPauwelsRVestboJTrial of Inhaled STeroids ANd long-acting beta2 agonists study groupCombined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trialLancet2003361935644945612583942

- ZaniniACherubinoFZampognaECroceSPignattiPSpanevelloABronchial hyperresponsiveness, airway inflammation, and reversibility in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruc Pulmon Dis20151011551161

- IqbalABarnesNCBrooksJIs blood eosinophil count a predictor of response to bronchodilators in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? results from post hoc subgroup analysesClin Drug Invertig20153510685688

- SchleichFNChevremontAPaulusVImportance of concomitant local and systemic eosinophilia in uncontrolled asthmaEur Respir J20144419710824525441

- KulkarniNSHollinsFSutcliffeAEosinophil protein in airway macrophages: a novel biomarker of eosinophilic inflammation in patients with asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol20101261616920639010

- WoodruffPGAgustiARocheNSinghDMartinezFJCurrent concepts in targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pharmacotherapy: making progress towards personalised managementLancet201538599791789179825943943

- GhebreMABafadhelMDesaiDBiological clustering supports both “Dutch” and “British” hypotheses of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Allergy Clin Immunol20151351637225129678

- BrusselleGBrackeKTargeting immune pathways for therapy in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Am Thorac Soc201411Suppl 5S322S32825525740