Abstract

Background

We aimed to study the adverse outcomes of symptomatic and asymptomatic non-obstructed individuals and those with mild COPD longitudinally in participants from three Latin-American cities.

Methods

Two population-based surveys of adults with spirometry were conducted for these same individuals with a 5- to 9-year interval. We evaluated the impact of respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, wheezing or dyspnea) in non-obstructed individuals, and among those classified as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 1, COPD on exacerbation frequency, mortality and FEV1 decline, compared with asymptomatic individuals without airflow obstruction or restriction.

Results

Non-obstructed symptomatic individuals had a marginal increased risk of mortality (HR 1.3; 95% CI 0.9–1.94), increased FEV1 decline (−4.5 mL/year; 95% CI −8.6, −0.4) and increased risk of 2+ exacerbations in the previous year (OR 2.6; 95% CI 1.2–6.5). Individuals with GOLD stage 1 had a marginal increase in mortality (HR 1.5; 95% CI 0.93–2.3) but a non-significant impact on FEV1 decline or exacerbations compared with non-obstructed individuals.

Conclusions

The presence of respiratory symptoms in non-obstructed individuals was a predictor of mortality, lung-function decline and exacerbations, whereas the impact of GOLD stage 1 was mild and inconsistent. Respiratory symptoms were associated with asthma, current smoking, and the report of heart disease. Spirometric case-finding and treatment should target individuals with moderate-to-severe airflow obstruction and those with restriction, the groups with consistent increased mortality.

Introduction

COPD is the third leading cause of death in the world.Citation1 It has been considered a consequence of rapid lung-function decline, but also the consequence of poor lung development either before or after birth.Citation2

In the Proyecto Latinoamericano de Investigación en Obstrucción Pulmonar (PLATINO) study population, we described cross-sectionally the main characteristics of COPD in a population-based sample,Citation3 and longitudinally, mortality rates and lung-function decline according to COPD status in three Latin America metropolises (the PLA-TINO follow-up study).Citation4 In this study individuals with post-bronchodilator (post-BD) Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second/Forced Vital Capacity (FEV1/FVC)<0.70 and FEV1 ≥80% predicted (%P) known as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 1 groupCitation5 or mild COPD was by far the most numerous group of COPD found (8.5% of the population studied in PLATINO, and 59% of identified COPD). The Burden of Obstructive Lung Diseases (BOLD) study reported a prevalence of GOLD 1 ranging from 1.4% to 15.5%, with an average of 8.1%.Citation6 In addition, false-positives in this group are frequent in advanced age, especially if the fixed ratio is used for the diagnosis of airflow obstruction.Citation7 Furthermore, interventions specifically designed for mild COPD are nearly nil, in that the majority of clinical trials select individuals with reduced FEV1, frequently FEV1 <60%P. In the PLATINO’s longitudinal study, the FEV1 was the main predictor of survival,Citation4 as well as a predictor of lung-function decline.Citation8 As GOLD stage 1 (mild COPD) individuals have a normal FEV1 by definition, we would expect a mild or non-significant impact on these outcomes.

Lung-function decline in GOLD stage I COPD patients was assessed previously in one large cohort, and asymptomatic participants had a slightly slower decline than those with chronic cough and phlegm.Citation9 On the other hand, exacerbations have been associated with accelerated lung-function loss in subjects with established COPD, particularly those with mild disease.Citation10 Recently, the relevance of respiratory symptoms in the prognosis, treatment selection and the natural history of COPD, especially in individuals with no airflow obstruction, has been emphasized,Citation11 as well as the impact of mild airflow obstructionCitation12 and both were considered a relevant research issue by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Thoracic Society (ERS).Citation13 Therefore, we conducted this study to determine the association of the presence of respiratory symptoms in non-obstructed individuals and of mild COPD with lung-function decline, exacerbations and mortality in COPD subjects from two population-based surveys.

Method

The study protocol for the baseline study was approved by the ethics committee of the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias de Mexico, the Universidad Central de Venezuela, the Universidad Federal de Pelotas, and Universidad Federal de São Paulo in Brazil, the Universidad Pontificia Católica de Chile, and Hospital Maciel, Universidad de la República in Uruguay; the latter four approved the follow-up study. Participants signed an informed consent.

The detailed methods of the PLATINO baselineCitation14 and follow-up studiesCitation15 are available elsewhere. Between the years 2003 and 2005, population-based surveys were conducted employing standardized methodology in five large Latin-American metropolitan areas: Sao Paulo (Brazil); Mexico City (Mexico); Montevideo (Uruguay); Santiago (Chile) and Caracas (Venezuela). We successfully interviewed 1,000 subjects aged 40 years or older in Sao Paulo, 1,063 in Mexico City, 943 in Montevideo, 1,208 in Santiago and 1,357 in Caracas. Spirometry testing was performed in 963 (97.9%) subjects in Sao Paulo, 1,000 (98.3%) in Mexico City, 885 (97.1%) in Montevideo, 1,173 (99.8%) in Santiago and 1,294 (98.4%) in Caracas.Citation3 The questionnaire, available at the PLATINO website,Citation36 is comparable to that used in the BOLD study,Citation14 and included sections of the American Thoracic Society Division of Lung Diseases (ATS/DLD), European Community Respiratory Health Survey II, Lung Health Study instruments, the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale and questions from the SF12 (a 12-item short form health survey) to assess overall health status.Citation14

Spirometry was performed using an ultrasonic spirometer (EasyOne; ndd Medical Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland) before (pre-BD) and 15 minutes after the administration of 200 µg of Salbutamol (post-BD) according to the ATS criteria of acceptability and reproducibilityCitation16 with >90% of the tests fulfilling the ATS quality criteria.

Follow-up studies were conducted in Montevideo, Santiago and Sao Paulo 5, 6 and 9 years after the baseline surveys, respectively. Individuals were visited at their homes based on the contact information provided by them during the baseline exam.Citation15

GOLD lung-function criteria for defining COPD was utilized: a post-BD FEV1/FVC <0.70, with staging based on the percentage predicted for FEV1: FEV1,%P ≥ 80= Stage I (mild COPD); FEV1,%P ≥50 and <80= Stage II; FEV1,%P ≥ 30 and <50= Stage III; FEV1,%P <30= Stage IV.Citation5 GOLD stages 2–4 defined as FEV1/FVC <0.7 and FEV1 <80%P were also analyzed for increasing the specificity of the COPD diagnosis. Restriction was defined as a post-BD FVC <80%P and a FEV1/FVC ≥0.7,Citation17 to be consistent with GOLD stages.

We estimated the association of spirometric GOLD stages, with a set of adverse outcomes obtained during the survey (death, annual decline in FEV1, and the report of 2+ exacerbations in the previous year of second survey). Our reference group was the non-obstructed non-restricted asymptomatic participants: those who lacked a report of cough, phlegm (both even without a cold), wheezing (in the last year) and dyspnea (dyspnea ≤1 according to the MRC scale). Adverse outcomes, especially death,Citation4 as well as lung-function decline,Citation8 were analyzed previously in detail, including the main risk factors. However, the aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of mild COPD and respiratory symptoms on decline, death and exacerbations. For the purpose of this study, COPD exacerbation was self-reported and defined by symptoms using the following questionsCitation18: 1) Have you ever had a period where your breathing symptoms got so bad that they interfered with your usual daily activities or caused you to miss work? 2) How many such episodes have you had in the past 12 months? 3) For how many of these episodes did you need to see a doctor in the past 12 months? 4) For how many of these episodes were you hospitalized in the past 12 months?

The risk of death during follow-up was estimated by fitting Cox proportional-hazard models, while the risk of two or more exacerbations in the previous year was calculated by fitting a logistic regression model, and the annual decline in post-BD FEV1 (mL/year) was calculated by subtracting the second measurement from the first and dividing the difference between the exact number of years between the two examinationsCitation8 in a multiple linear regression model.

As co-variables, we analyzed age; gender; current smoking (expressed as yes or no and also by the number of cigarettes smoked per day); cumulative smoking in pack-years; obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2); years of education as an indicator of socioeconomic status; hour-years of exposure to biomass smoke while cooking (average number of years exposed multiplied by the average hours per day exposed); years of exposure to an occupation with dust, smokes or gases; previous physician diagnosis of asthma, COPD, diabetes or heart disease; or respiratory hospitalizations as children, obtained from a questionnaire. Utilization of health services was explored by the report of the use of any respiratory medication, exacerbations in the previous year requiring hospitalization, physician consultation or leading to missing days of work. We queried about self-perception of good or excellent health, feeling depressed or with little energy or calm.

Chronic bronchitis was defined as chronic phlegm (or chronic cough and phlegm) on the majority of the days of the week for 3 months of the year for two consecutive years.Citation19

Results

Follow-up evaluations were conducted for 885 adults in Montevideo, 1,173 in Santiago and 963 in Sao Paulo; information was obtained for 758 (85.6%), 993 (84.7%) and 748 (77.7%) subjects, respectively. Among these, 2,026 had a good quality post-BD spirometry test in both examinations. Follow-up rates for each independent-variable category were around 80%.Citation15 During follow-up, a total of 301 deaths among participants were documented.

The clinical characteristics in the two evaluations have been previously presented.Citation4,Citation8 Compared with the first examination, individuals with a follow-up exam were older, with less current smoking, and with slightly lower lung function.

describes the characteristics of the analyzed groups: non-obstructed and non-restricted individuals, (FEV1/FVC ≥0.7, FVC ≥80%P), asymptomatic (n=942; 31.2%), the reference group, and symptomatic (n=1,355; 44.9%), the restricted group (n=200; 6.6%), and the obstructed groups: GOLD stage 1 (n=323; 10.7%) and GOLD stages 2–4 or moderate-to-severe (n=201; 6.7%). As airflow obstruction increases there is tendency toward an increase the age, asthma, chronic bronchitis, previous tuberculosis (TB), and exposure to occupations involving dust, whereas the BMI decreases in the severely obstructed patients. Non-obstructed symptomatic individuals tend to concentrate a larger proportion of women with a previous diagnosis of asthma or COPD, currently smoking and with more frequent exacerbations in comparison with the asymptomatic non-obstructed individuals. Use of respiratory medications, missing days of work, hospitalizations and physician consultations associated with exacerbations, as well as poor perception of health were higher in symptomatic non-obstructed individuals and in those with more severe obstruction (). Table S1 separates GOLD stage 1 into asymptomatic (n=100) and symptomatic individuals (N=223) the latter also with a higher proportion of women, previous asthma, current smoking, more use of respiratory medications and a more uncommon perception of good or excellent heath than the asymptomatic group.

Table 1 Characteristics of the baseline groups of obstruction/respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, dyspnea or wheezing) evaluatedTable Footnote*

describes the association (odds ratio [OR] and 95% CI) of GOLD stages with the outcomes analyzed in the COPD population, unadjusted and adjusted by age, gender, BMI, education, comorbidities and smoking (adjusted 1) and all of the previous plus FEV1 post-BD (adjusted 2). The rate of deaths and frequent exacerbations tended to increase as the severity of airflow obstruction increased and in the restricted group, this mainly attributable to reduced FEV1 as an impact of the GOLD stage on mortality and exacerbations was considerably reduced adjusting by FEV1 (, adjusted 2 column). Similar models with GOLD stage 1 separated into asymptomatic and symptomatic groups are described in Table S2.

Table 2 Adjusted association (OR 95% CI) between GOLD stage at baseline, deaths, lung-function decline and exacerbations in the follow-up visit, with respiratory symptoms evaluated as cough, phlegm, dyspnea or wheezing

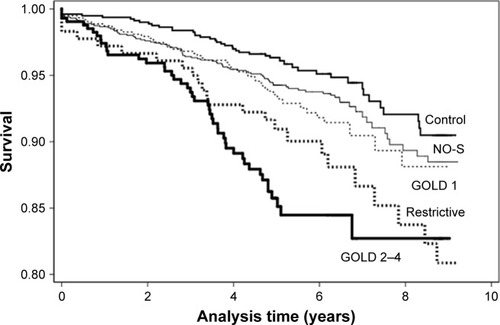

The presence of respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough or phlegm or wheezing) in non-obstructed individuals slightly increases the risk of death (adjusted HR 1.3, 95% CI 0.90–1.94), whereas it significantly increases the risk of frequent exacerbations (OR 2.6; 95% CI: 1.24–6.5) and lung-function decline (−4.5 mL/year) in excess to reference; 95% CI: −8.6, −0.36) adjusting for age, gender, BMI, education, comorbidities, smoking and FEV1 post-BD () ().

Figure 1 Survival curves of non-obstructed, non-restricted individuals with respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, dyspnea or wheezing), non-obstructed symptomatic (NO-S) and asymptomatic (Control), compared with those with airflow obstruction GOLD stage 1 (GOLD 1), GOLD stages 2–4 (GOLD 2–4), and restrictive pattern, adjusted by mean age (57 years), feminine gender, education, pack-years of smoking and comorbidities (as in Adjusted 1 column, ).

Abbreviation: GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Symptoms in non-obstructed individuals were associated with a prior diagnosis of asthma (OR 4.7; 95% CI: 3.5–6.3) or heart disease (OR 2.2; 95% CI: 1.7–2.8), with feminine gender (OR 1.5; 95% CI: 1.3–1.8), current smoking (OR 3.1; 95% CI: 2.6–3.8), passive smoking (OR 1.2; 95% CI: 1.02–1.4) and previous dusty occupations (OR 1.5; 95% CI: 1.2–1.7), in a multivariate logistic regression model. Asthma, wheezing and current smoking were also significantly associated with other combinations of symptoms: cough/phlegm, cough/phlegm/dyspnea or chronic bronchitis, whereas a report of heart disease, passive smoking or occupational exposure was associated with some of these (See Table S3). Among the 1,355 non-obstructed symptomatic individuals, 36.1% were current smokers, 18.7% had a previous medical diagnosis of asthma, 40.1% were exposed to passive smoke, 2.7% were exposed to biomass smoke (26% were exposed previously), 56.0% worked previously in a dusty occupation and 18.9% reported the presence of heart disease. A total of 87% of the non-obstructed symptomatic subjects had at least one of the described risk factors compared with 74% of the asymptomatic individuals.

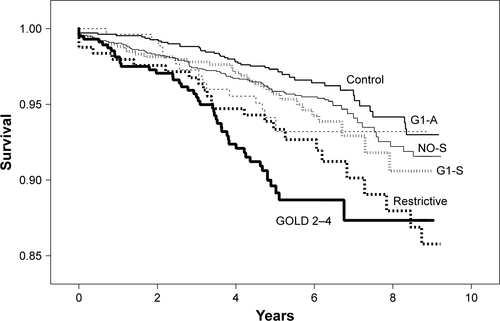

Mild COPD was weakly associated with increased mortality (HR 1.5; 95% CI, 1.01–2.3), but not with increased risk of exacerbation (OR 2.8; 95% CI, 0.8–9.06), nor a faster lung-function decline (−0.35 mL/year; 95% CI −7.0; +6.2) adjusting for age, gender, BMI, education, smoking and comorbidities (see , and Figure S1).

Moderate and severe airflow obstruction (GOLD stages 2–4) consistently increased the risk of death (HR 2.95, 95% CI 1.9–4.5, and Figure S1), and frequent exacerbations (OR 7.5, 95% CI; 2.5–22.1) whereas this did not predict a more pronounced decline in lung function unless adjusted by baseline post-BD FEV1 (the most relevant predictor) (). Individuals with a spirometric restrictive pattern had increased the risk of death (HR 2.34, 95% CI 1.4–3.8) and frequent exacerbations (OR 5.0, 95% CI 1.4–14.9) but not increased FEV1 decline (, )

GOLD stages 2–4, not present in the first evaluation, appeared in 55 individuals in the second (incident GOLD 2–4), distributed at baseline more frequently in the symptomatic groups (non-obstructed and with GOLD stage 1) (Table S4). Significant predictors of incident GOLD 2–4 included the presence of symptoms at baseline (OR 2.1; 95% CI, 1.0–4.3), as well as asthma (OR 2.9; 95% CI, 1.5–5.5), masculine gender (OR 2.5; 95% CI, 1.4–4.5) and current smoking (OR 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0–3.2) (see Table S5, Adjusted 1), but baseline post-BD FEV1 was the most relevant predictor (OR 0.34; 95% CI, 0.21–0.55) and once included in the model (see Table S5, Adjusted 2), the association with symptoms disappeared but persisted with asthma or smoking.

Discussion

We have described the association of the presence of symptoms in non-obstructed individuals and of mild COPD (GOLD stage 1) with several remarkable outcomes (death, frequent exacerbations, airflow obstruction and lung-function decline) in a population-based follow-up study carried out in three Latin-American cities. We found that respiratory symptoms in non-obstructed individuals and mild airflow obstruction, in adjusted models, had mild adverse outcomes compared with those of asymptomatic non-obstructed individuals, whereas individuals with a reduced FEV1% (GOLD stages 2–4) or reduced FVC entertain a substantially increased risk of death and exacerbations. In addition, non-obstructed symptomatic individuals exhibit in general a slightly faster decline in FEV1.

Several studies have found adverse outcomes in symptomatic individuals and in those with mild COPD. In one population-based study,Citation9 individuals with symptomatic stage 1 COPD had a faster decline in FEV1 (−9 mL/year in excess to reference), increased respiratory-care utilization (OR 1.6) and a lower quality of life than asymptomatic subjects with normal lung function.Citation9 These changes were not observed in individuals with asymptomatic stage 1 COPD. In the COPDGene study,Citation10 27.4% of GOLD stage 1 patients experienced a mean exacerbation rate/year of 0.18 compared with 0.13 of GOLD stage-0 and 0.89 of GOLD stage-4 patients, respectively. From 745 participants with GOLD stage 1 (from a total of approximately 4,000 patients with COPD), only 55% reported being exacerbation-free, 20% reported two or more exacerbations in the previous year and 9.6% reporting one or more hospitalizations.Citation20

The results of the present manuscript reinforce first, the efforts to identify systematically individuals with moderate and severe airflow obstruction (GOLD stages 2–4), characterized by a reduced FEV1, the main predictor of increased death rateCitation4 and of decline in lung functionCitation8 as well as those with reduced FVC <80%P, with a restrictive spirometric pattern. Second, in contrast to previous studies,Citation9,Citation10 we observed mild adverse outcomes of GOLD stage 1, supporting the recommendations of prioritize the identification of moderate-to-severe COPD.Citation21,Citation22 Individuals with GOLD stage 1, comprise a numerous group among population-based cohorts (8.4% of the total PLATINO population in baseline) compared with GOLD stages 2–4 (5.6%). Expenses and efforts to identify spirometrically undiagnosed COPD would be considerably reduced focusing for moderate-to-severe airflow obstruction, what can be achieved for example by selecting for diagnostic spirometry individuals with a reduced PEFR or simplified spirometry.Citation23,Citation24 Individuals with moderate-to-severe COPD are precisely those with more proved beneficial interventions in addition to stopping smokingCitation21,Citation22 as most controlled clinical trials testing medications for COPD exclude individuals with mild airflow obstruction.

Third, in line with previous studiesCitation11 the presence of respiratory symptoms in non-obstructed individuals requires further evaluation as adversely impact prognosis. In our study, any combination of respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, dyspnea or wheezing, but also classic chronic bronchitis) in non-obstructed individuals was associated with previous diagnosis of asthmaCitation10 or wheezing in the last year, and this may suggest asthma undertreatment and underdiagnosis. Symptoms were also associated with current smoking, passive smoking, exposure to dusty occupations and a report of a heart disease. Those lacking one of the explored risk factors in the present study could include several respiratory diseases, gastroesophageal reflux or upper airway diseases, which require detailed evaluation and specific treatment.

Smokers with mild airflow obstruction, and also non-obstructed smokers, may present gas exchange abnormalities and exercise limitationCitation12,Citation25–Citation32 or significant changes of emphysema on CT scanning.Citation33,Citation34 In fact, phenotyping individuals with mild COPD based on CT alterations has been proposed.Citation35 The persistently symptomatic population feels unhealthy, utilizes more health services and has adverse outcomes, although fewer of these than individuals with moderate-to-severe airflow obstruction. Therefore efforts to stop smoking and exposures and treating properly asthma should be emphasized as priorities for symptom management.

As limitations, we have observed these subjects on solely two occasions and were able to perform a second evaluation only in three cities from the five done the baseline. In addition, the percentage of individuals with severe airflow obstruction is small, although the main objective of the study was to compare GOLD stage 1, with non-obstructed individuals. Second, we utilized a definition of exacerbation based on subjects’ report of breathing symptoms, interfering with daily activities or work, but also identified those events requiring a physician visit or hospitalization, likely less subject to inaccurate recall.

The main strengths of this study include the population-based sampling, the high quality of the post-BD spirometry tests,Citation4 and the relatively high rates of follow-up after 6–9 years. In contrast to the large COPD cohorts, our population-based study has a proper non-obstructed population control key for numerous relevant comparisons, with and without respiratory symptoms, previous smoking or abnormalities in FVC.

Conclusion

The presence of respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, wheezing, dyspnea) in non-obstructed individuals as well as mild airflow obstruction demonstrated a mild adverse impact on mortality and exacerbations and were associated with current smoking, exposure to other pollutants and bronchial asthma, requiring among other things improved anti-smoking strategies in health care. Individuals with reduced FEV1 or FVC (moderate-to-severe airflow obstruction and those with spirometric restriction) had the highest mortality risk and constitute a priority target for diagnosis and treatment.

Author contributions

AMB Menezes coordinated the PLATINO study. MV Lopez and A Muiño were the principal investigators (PIs) in the follow-up in Montevideo. G Valdivia was the PI in Santiago. JR Jardim was the PI in São Paulo. M Montes de Oca was the PI in the PLATINO baseline in Caracas. R Perez-Padilla was responsible for the spirometry control, wrote the first draft of the manuscript with AMB Menezes and FC Wehrmeister and conducted with FC Wehrmeister the statistical analysis. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax (ALAT) for helping in the design of the project and for funding part of the project. We also thank Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis for funding the study. The PLATINO study has been sponsored by ALAT, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis for the collection of the data during the field work. The PLATINO group for this project included Dolores Moreno (Pulmonary Division, Hospital Universitario de Caracas, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela), Julio Pertuze (Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile), Carmen Lisboa (Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile), and Oliver A Nascimento, Mariana R Gazzotti, Graciane Laender, and Beatriz Manzano (Federal University of Sao Paulo -Brazil).

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 Survival curves of non-obstructed non-restricted individuals with respiratory symptoms (cough, phlegm, dyspnea or wheezing), non-obstructed symptomatic (NO-S) and asymptomatic (Control), compared with those with spirometric restrictive pattern and airflow obstruction GOLD stage 1, with symptoms (G1-S) and asymptomatic (G1-A), and GOLD stages 2–4 (GOLD 2–4), adjusted by mean age (57 years), feminine gender, education, pack-years of smoking and comorbidities (as in Adjusted 1, Table S2).

Notes: Non-obstructed symptomatic individuals (NO-S) had less survival than controls and stage-1 asymptomatic individuals but better outcome than individuals with moderate-to-severe airflow obstruction, and restrictive pattern. In Table S1, the characteristics of each group, including the participants, are depicted.

Abbreviation: GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Table S1 Characteristics of the baseline groups of obstruction/respiratory symptoms evaluated as cough, phlegm, dyspnea or wheezing separating GOLD stage 1 into symptomatic and asymptomaticTable Footnote*

Table S2 Adjusted association (OR 95% CI) between GOLD stage at baseline, deaths, lung function decline and exacerbations in the follow-up visit

Table S3 Associations between the presence of symptoms and several risk factors

Table S4 Predictors of incident COPD, GOLD stages 2–4

Table S5 Predictors of incident GOLD 2–4

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GBD 2016 Causes of Death CollaboratorsGlobal, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016Lancet2017390101001151121028919116

- LangePCelliBAgustíALung-Function Trajectories Leading to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseN Engl J Med2015373211112226154786

- MenezesAMPerez-PadillaRJardimJRChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence studyLancet200536695001875188116310554

- MenezesAMPérez-PadillaRWehrmeisterFCFEV1 is a better predictor of mortality than FVC: the PLATINO cohort studyPLoS One2014910e10973225285441

- GOLDGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPDGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)2018 Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdfAccessed September 24, 2018

- BuistASMcBurnieMAVollmerWMInternational variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence studyLancet2007370958974175017765523

- HardieJABuistASVollmerWMEllingsenIBakkePSMørkveORisk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokersEur Respir J20022051117112212449163

- Pérez-PadillaRFernandez-PlataRMontes de OcaMLung function decline in subjects with and without COPD in a population-based cohort in Latin-AmericaPLoS One2017125e017703228472184

- BridevauxPOGerbaseMWProbst-HenschNMSchindlerCGaspozJMRochatTLong-term decline in lung function, utilisation of care and quality of life in modified GOLD stage 1 COPDThorax200863976877418505800

- DransfieldMTKunisakiKMStrandMJAcute Exacerbations and Lung Function Loss in Smokers with and without Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195332433027556408

- Rodriguez-RoisinRHanMKVestboJWedzichaJAWoodruffPGMartinezFJChronic respiratory symptoms with normal spirom-etry. A reliable clinical entity?Am J Respir Crit Care Med20171951172227598473

- RossiAButorac-PetanjekBChilosiMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease with mild airflow limitation: current knowledge and proposal for future research – a consensus document from six scientific societiesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017122593261028919728

- CelliBRDecramerMWedzichaJAAn official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Research questions in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20151917e4e2725830527

- MenezesAMVictoraCGPerez-PadillaRPLATINO TeamThe Platino project: methodology of a multicenter prevalence survey of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in major Latin American citiesBMC Med Res Methodol200441515202950

- MenezesAMMuiñoALópez-VarelaMVA population-based cohort study on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Latin America: methods and preliminary results. The PLATINO Study Phase IIArch Bronconeumol2014501101724332830

- Spirometry SofUpdate. American Thoracic SocietyAm J Respir Crit Care Med1995152110711367663792

- ManninoDMBuistASPettyTLEnrightPLReddSCLung function and mortality in the United States: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey follow up studyThorax200358538839312728157

- Montes de OcaMTálamoCHalbertRJFrequency of self-reported COPD exacerbation and airflow obstruction in five Latin American cities: the Proyecto Latinoamericano de Investigacion en Obstruccion Pulmonar (PLATINO) studyChest20091361717819349388

- de OcaMMHalbertRJLopezMVThe chronic bronchitis phenotype in subjects with and without COPD: the PLATINO studyEur Respir J2012401283622282547

- CorradoARossiAHow far is real life from COPD therapy guidelines? An Italian observational studyRespir Med2012106798999722483189

- Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: recommendation statementAm Fam Physician200980885319835346

- Preventive ServicesUSForceTaskScreening for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Recommendation StatementAm Fam Physician2016942

- Franco-MarinaFFernandez-PlataRTorre-BouscouletLEfficient screening for COPD using three steps: a cross-sectional study in Mexico CityNPJ Prim Care Respir Med2014241400224841708

- Perez-PadillaRVollmerWMVázquez-GarcíaJCCan a normal peak expiratory flow exclude severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?Int J Tuberc Lung Dis200913338719275802

- BurtscherMHaiderTDomejWIntermittent hypoxia increases exercise tolerance in patients at risk for or with mild COPDRespir Physiol Neurobiol200916519710319013544

- ChavannesNVollenbergJJvan SchayckCPWoutersEFEffects of physical activity in mild to moderate COPD: a systematic reviewBr J Gen Pract20025248057457812120732

- ChenSWangCLiBRisk factors for FEV1 decline in mild COPD and high-risk populationsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171243544228184155

- ElbehairyAFWebbKANederJAAlberto NederJO’DonnellDEShould mild COPD be treated? Evidence for early pharmacological interventionDrugs201373181991200124214364

- JácomeCMarquesAImpact of pulmonary rehabilitation in subjects with mild COPDRespir Care201459101577158224803497

- NederJAO’DonnellCDCoryJVentilation Distribution Heterogeneity at Rest as a Marker of Exercise Impairment in Mild-to-Advanced COPDCOPD2015123252259

- O’DonnellDENederJAElbehairyAFPhysiological impairment in mild COPDRespirology201621221122326333038

- ElbehairyAFGuenetteJAFaisalAMechanisms of exertional dyspnoea in symptomatic smokers without COPDEur Respir J201648369470527492828

- JonesJHZeltJTHiraiDMEmphysema on Thoracic CT and Exercise Ventilatory Inefficiency in Mild-to-Moderate COPDCOPD201714221021827997255

- ReganEALynchDACurran-EverettDClinical and Radiologic Disease in Smokers With Normal SpirometryJAMA Intern Med201517591539154926098755

- LeeJHChoMHMcDonaldMLPhenotypic and genetic heterogeneity among subjects with mild airflow obstruction in COPDGeneRespir Med2014108101469148025154699

- Proyecto Latinoamericano de Investigación en Obstrucción Pulmonar (PLATINO)PLATINO Questionnaire Available from: http://www.platinoalat.org/docs/cuestionario_platino_mexico.pdfAccessed September 24, 2018 Spanish