Abstract

COPD is the third-largest killer in the world, and certainly takes a toll on the health care system. Recurrent COPD exacerbations accelerate lung-function decline, worsen mortality, and consume over US$50 billion in health care spending annually. This has led to a tide of payment reforms eliciting interest in strategies reducing preventable COPD exacerbations. In this review, we analyze and discuss the evidence for COPD action plan-based self-management strategies. Although action plans may provide stabilization of acute symptomatology, there are several limitations. These include patient-centered attributes, such as comprehension and adherence, and nonadherence of health care providers to established guidelines. While no single intervention can be expected independently to translate into improved outcomes, structured together within a comprehensive integrated disease-management program, they may provide a robust paradigm.

Introduction

COPD is a leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of almost 10% in adults aged ≥40 years.Citation1 Approximately 50% of patients with COPD have at least one exacerbation per year, and over 20% are readmitted within 30 days, with a total of nearly 800,000 hospitalizations and US$50 billion in health care costs annually.Citation2–Citation4 This has led the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to impose financial penalties for hospitals with 30-day readmissions after COPD exacerbations, as part of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Consequently, it is not surprising that last few years have seen a significant interest in self-management strategies to reduce recurrent exacerbations and hospitalizations. The aim of this review was to examine the utility of COPD action plan-based self-management strategies in acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) and discuss its impact on outcomes.

Action plans: definitions and components

Action plans have been well studied in asthma for decades, and have had more of an established role compared to COPD. A PubMed search (conducted November 2015) for “action plans” along with “asthma” yielded over 400 results compared to 69 results for “COPD”. Traditionally defined as a personalized document generated by health professionals, action plans are intended to promote self-management of exacerbations that may otherwise necessitate acute care, via the patient’s early recognition of an exacerbation and self-initiation of interventions (typically antibiotics and oral corticosteroids). Asthma action plans rely on the variability in symptomatology and peak expiratory flow thought to reflect changes in asthma severity. Although not shown to improve mortality and morbidity, these appear to be protective against severe asthma exacerbations.Citation5,Citation6 More recent data, however, suggest that asthma action plans may not confer additional benefit to patients already receiving subspecialty care.Citation7 COPD action plans on the other hand have been sparsely investigated.

Role of steroids in COPD exacerbations

For decades, oral steroids have played a quintessential role in the management of hospitalized patients with AECOPD. Two previous randomized controlled trials – a Veterans Affairs studyCitation8 and a similar studyCitation9 – demonstrated that corticosteroids played an integral role in treating inpatient AECOPD. A recent review by Self et alCitation10 specifically investigating the role of oral steroids in the setting of COPD action plans found that twoCitation11,Citation12 (of five) published randomized controlled trials containing a total of 933 patients provided evidence of reduced rates of hospitalization by the use of comprehensive COPD action plans, while the othersCitation13–Citation15 showed no differences in rates of rehospitalization. While there was no effect on overall mortality, oral steroids appeared to increase time to next exacerbation.

COPD action plans universally integrate oral steroids in the self-management of AECOPD. However, there is no consensus on the length of corticosteroid therapy. Among hospitalized patients, prior studies have shown that a 2-week therapy course was equivalent or noninferior to extended 6-week tapers of corticosteroids after COPD exacerbations.Citation16 More recently, a randomized controlled trial enrolled 314 COPD patients that had presented to the emergency room (ER) for acute exacerbations (289 were admitted), and randomized them to 5 days versus 14 days of 40 mg prednisone therapy. The authors reported that a 5-day course of prednisone was noninferior to a 14-day course in terms of likelihood of exacerbation in the subsequent 180 days, time to next exacerbation, and hospital readmissions.Citation17 A systematic review comparing different durations of oral steroids similarly concluded that a 5-day course might be comparable to a 14-day course for most patients.Citation18 These data suggest that a 5-day course may be adequate in treating AECOPD. While oral steroids have been shown to be equally efficacious to systemic steroids in hospitalized patients,Citation19 few studies have compared the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids to oral steroids.Citation20 Inhaled steroids have not been studied in the setting of an action plan for AECOPD, which typically utilizes short courses of oral steroids.

Role of antibiotics in COPD exacerbations

The majority of patients with AECOPD are treated with antibiotics. However, the efficacy of antibiotics remains less certain for outpatient (versus inpatient) treatment of AECOPD, partly due to the available data being mainly from prospective nonrandomized studies (). Earlier studies have shown an overall decrease in treatment failures (resolution of symptoms), as well as relapse rates, in patients with AECOPD that received antibiotics when compared to patients that did not receive outpatient antibiotics.Citation21,Citation22 Also the presence of green (purulent) sputum was found to be 94.4% sensitive and 77% specific for the yield of a high bacterial load and the likelihood of patients to benefit most from antibiotic therapy.Citation23 A subsequent study by Allegra et al indicated that change in sputum color, especially from yellowish to brownish, was associated with bacterial exacerbations, and their study found an increased yield of Gram-negative and Pseudomonas aeruginosa/Enterobacteriaceae-type organisms.Citation24 In contrast, in a smaller study (n=22), Brusse-Keizer et al found a weak association between bacterial load and sputum color in patients admitted with AECOPD.Citation25

Table 1 Summary of studies evaluating effectiveness of COPD action plan

More recently, Llor et al showed in a randomized trial of antibiotics for exacerbations of mild-to-moderate COPD that antibiotic use was associated with a higher chance of clinical cure, as well as longer time to next exacerbation.Citation26 Using data from the placebo arm of this trial, Miravitlles et al evaluated predictors of failure (defined as incomplete resolution, persistence, or worsening of symptoms that require treatment or hospitalization) without antibiotics. They reported that increase in sputum purulence and elevated C-reactive protein concentration was associated with an increased risk of failure without antibiotics.Citation27 Roede et al reported in a population-based cohort study that adding antibiotics to oral steroids was associated with a reduced risk of subsequent exacerbation, especially in patients with recurrent exacerbations, and also reduced risk of all-cause mortality.Citation28

Overall, while these data do not suggest robust efficacy, they do justify the clinical practice of addition of antibiotics for the management of AECOPD, particularly when recurrent and associated with sputum purulence (). Choosing an optimal antimicrobial agent remains one of the challenges, since a third to two-thirds of exacerbations may be caused by viruses, while bacterial infections appear to trigger about half of AECOPD.Citation29,Citation30

Self-management using COPD action plans and outcomes

Although COPD action plans have not been formally investigated, several studies have included them as part of a comprehensive-care program (in patients with at least one exacerbation in the preceding year), and reported their effects on reducing ER visits, hospital admissions, and/or overall effect on quality of life (). A recent Cochrane review concluded that self-management interventions in patients with COPD are associated with improved health-related quality of life and reduction in respiratory-related hospital admissions.Citation31

Table 2 Summary of studies investigating role of antibiotics in COPD exacerbation

In a prospective randomized controlled trial, Bourbeau et al evaluated the effect of disease-specific self-management intervention on hospitalizations in COPD patients.Citation11 COPD patients with at least one hospitalization for COPD in the previous year were divided into a usual-care group and a self-management group. Patients in the self-management group received comprehensive patient education along, with a customized action plan that consisted of a symptom-monitoring list and prescriptions consisting of antibiotics and oral steroids for 10–14 days to be initiated promptly when symptom changes were noted. The study noted a significant decrease in hospital admissions and exacerbation rates in the self-management group when compared to the usual-care group.

In another randomized controlled trial, Sridhar et al used a hospital database to identify patients admitted for AECOPD in the 4 years prior to the study who had not previously undergone pulmonary rehabilitation (PR).Citation13 All patients randomized to the intervention group (versus usual care) underwent PR and self-management education and were given a written COPD action plan. Nurses made monthly telephone calls and quarterly home visits for a period of 2 years and reinforced self-management education. While the authors found no difference in the rate of hospital readmissions, there was an overall reduction in the number of urgent outpatient physician visits, with a number needed to treat of 1.79. Interestingly, there was a significant reduction in COPD-related deaths in the intervention group (one of six deaths) compared to the control group (eight of 12 deaths; P=0.015).

In a retrospective analysis by Sedeno et al, COPD patients were randomly assigned to usual care or to a comprehensive self-management program that included a written action plan with prescription of antibiotics and prednisone for self-administration in the event of an exacerbation, and case-manager support with scheduled phone calls.Citation32 There were a total of 661 exacerbations among the 166 patients studied. While the authors did not find any difference in the frequency of exacerbations between the two groups, there was a significant decrease in exacerbations that led to hospitalizations in the action-plan group (17.2% vs 36.3%, P<0.001). This was associated with a change in patient behavior as part of self-management (more than 50% patients promptly self-treated their exacerbations with prescribed antibiotics and prednisone).

Effing et al prospectively studied the effects of self-management along with an action plan on severity of COPD exacerbations in patients that underwent a mandatory smoking-cessation program prior to randomization.Citation14 A total of 142 moderate-to-severe COPD patients were randomized to the control group (received self-management education alone) or the intervention group (also received action plan). There was a trend toward fewer exacerbation days and hospital admissions, which was statistically significant only in patients with high exacerbation days per year. Although the frequency of exacerbations was identical in both groups, the authors found a significant reduction in health care contact in the intervention group (P=0.043) that seemed to translate into cost savings.

Rice et al conducted a randomized controlled trial at five Veterans Affairs medical centers, where 743 patients with spirometrically confirmed COPD that were at high risk (hospitalization, home oxygen use, or steroid use in the prior year) of hospital admission were randomized to usual care or a simple disease-management arm.Citation12 Patients in the disease-management arm received a written action plan and an educational intervention, during which they attended a single 1- to 1.5-hour group-education session conducted by a respiratory therapist. This was followed by monthly phone calls made by the case manager. The study found a significant reduction in the frequency of COPD-related hospitalizations and ER visits (0.82 per patient in usual care versus 0.48 per patient in intervention group, P<0.001). Additionally, the study also reported a statistically significant decrease in incidence of hospitalizations for cardiac or pulmonary conditions other than COPD and for all causes of hospitalizations and ER visits. In contrast, Fan et al performed a randomized controlled trial in 426 COPD patients that had required hospitalization in the prior year and randomized them to usual care or comprehensive-care intervention (comprised of educational intervention and written action plan with prescriptions).Citation15 The education program run by case managers consisted of four individual 90-minute weekly sessions using an educational booklet, followed by group sessions, and monthly phone calls thereafter that were mainly focused on various aspects of self-management. The study found no difference in the incidence of exacerbations or COPD-related hospitalizations (27% versus 24%, P=0.62). Somewhat surprisingly, however, the study had to be prematurely terminated, due to increased mortality in the intervention group versus usual care (28 overall deaths versus ten, P=0.003; ten COPD-related deaths versus three, P=0.053; intervention group versus usual care, respectively). Of note, although the action plan was designed for patients to initiate treatment within 48 hours of onset of exacerbation symptoms, there was no difference in the actual initiation of treatment between the groups in either prednisone (6.4 days versus 7.7 days, P=0.48) or antibiotics (7 days versus 6.8 days, P=0.84). Interestingly, at a 6-month follow-up after the intervention was stopped, there was no significant difference in deaths (overall or COPD-related) between the groups.

Taken together, these data suggest that the available body of literature on use of action plans in COPD is at best inconclusive. While COPD action plans appear to improve some aspects of COPD exacerbations (reduce severity of exacerbations and/or hospitalizations), they are highly unlikely to have any impact on mortality (). Unfortunately, the studies lack standardization of action-plan constituents and are flawed with concurrent initiation of one or more self-management strategies, making it nearly impossible to determine which components may have contributed to reported benefit (or lack thereof).

Action plans and self-management strategies may be necessary but not sufficient to improve COPD outcomes

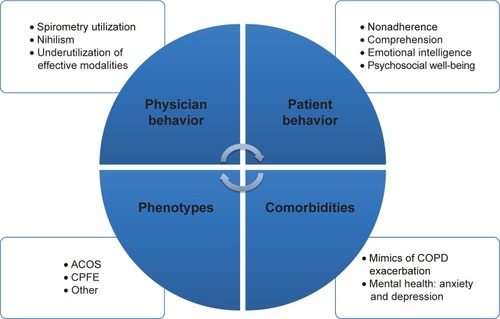

While empowering the patient to better understand the disease process and proactively collaborate with the treating generalist or specialist, self-management strategies still face several challenges limiting their ability to reduce COPD exacerbations and rehospitalizations effectively. When integrated into a multidisciplinary disease-management program, they may be effective in reducing health care utilization.Citation33 Limitations include patient-centered attributes, such as comprehension and what might be called emotional intelligence, which directly affect self-management abilities,Citation34–Citation36 as well as other factors that may not be addressed by simplistic strategies ().

Figure 1 COPD action plans: limitations and barriers.

Patient-centered attributes: psychosocial aspects of COPD

Self-management strategies in COPD often center upon the ability of the patient to identify an exacerbation and trigger the action plan. Therefore, the success of any action plan-based strategy would rely heavily on patient understanding and the ability to actually become effective self-managers. Unfortunately, patients with frequent exacerbations have been reported to have a poor understanding of the term “exacerbation”.Citation37 Just as PR improves exercise capacity but does not seamlessly translate into increased physical activity,Citation38,Citation39 prescription of an action plan cannot be assumed to translate into timely implementation of the same. Indeed, even in the setting of randomized controlled trials with systematic educational interventions, the majority of COPD patients did not implement self-management strategies as prescribed.Citation15,Citation40,Citation41 In one trial, only 42% (75 of 150 enrolled patients with AECOPD) were classified as being successful self-managers demonstrating appropriate use of self-management therapies.Citation41 It seems reasonable to assume that in clinical practice, patient adherence to action plans may be low.

Psychosocial factors may contribute to patient nonadherence toward both pharmacologic and nonpharmacological therapies. Further, exacerbations appear to take a toll on the psychosocial well-being of the patient, and this is underestimated by physicians.Citation37 Negative emotions and lack of psychosocial well-being have been strongly associated with patient nonadherence.Citation42,Citation43 A recent report associated emotional intelligence (the capacity to understand and manage personal thoughts and feelings positively influencing social well-being) in patients with COPD with self-management abilities independent of age and disease severity.Citation34 Interestingly, it is a trainable skill that may be learned and acquired at any age, and may represent a novel form of rehabilitation complementing existing strategies.

Spirometry underutilization

Physician adherence to recommended use of spirometry remains poor and poses a major challenge, especially since three of every four patients with obstructive lung disease have never had spirometry.Citation44–Citation46 How do we reconcile literature that suggests both underdiagnosisCitation47–Citation50 and overdiagnosisCitation45,Citation51–Citation53 of COPD? It is conceivable that there might in fact be an element of misdiagnosis. This had been well reported in the outpatient setting in patients with symptomatology of obstructive lung disease that were clinically diagnosed as COPD.Citation54–Citation56 More recently, we have reported misdiagnosis in patients with frequent exacerbations (more than two hospitalizations or ER visits in the prior year) of severe COPD and asthma.Citation45 Misdiagnosis was found in 26% (87 of 333) of patients, while another 12% (41 of 333) had obstructive lung diseases other than asthma and COPD. Interestingly, spirometry underutilization was found to be an independent risk factor for misdiagnosis. Uptake of major society guidelines requiring a spirometry confirmation of a diagnosis of COPD is disappointingly low.Citation44,Citation57 Prescribing empiric therapies with a clinical diagnosis of COPD (without spirometric confirmation) is the norm and not the exception in current clinical practice. In the real world (versus clinical trials), it may be unrealistic to expect self-management strategies designed for COPD to work in a population where the component of “O” (obstruction) and the very diagnosis is in doubt!

Comorbidities

The past decade has improved our understanding of COPD as more of a complex and polygenic disease. Most patients with COPD have major concomitant medical comorbidities that directly or indirectly worsen outcomes.Citation58 Up to 94% of patients have at least one comorbid disease, and almost half of all patients have more than three comorbidities.Citation58,Citation59 High prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea,Citation60 pulmonary embolism,Citation61 and heart failureCitation62 has been reported in a quarter to a half of patients with AECOPD. Although there is a distinct urge to diagnose (and treat) a smoker with cough as COPD, smoking-related pulmonary diseases themselves are a large group of distinct diseases, all of which may present with clinical symptomatology of COPD.Citation63–Citation65 An interesting study investigating the “comorbidome” of COPD evaluated the relationship between 79 comorbidities and risk of death in patients with COPD over a median of 51 months.Citation66 They found 12 comorbidities that negatively influenced survival and increased risk of death. Anxiety and depression have been increasingly identified in frequent exacerbators of COPD, and have recently been implicated to have a direct association with exacerbations and health care utilization.Citation67–Citation69 Patients on long-term oxygen therapy appear to be at risk.Citation70 Depression is a known risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment and poor outcomes.Citation42 Unfortunately, data suggest that up to two-thirds of patients with concomitant COPD and depression may not receive treatment for their depression.Citation71 Overall, these are missed opportunities for improving outcomes by addressing potentially treatable conditions, possibly within a multidisciplinary program.Citation33

These data beg the question of whether a subset of COPD patients with recurrent hospitalizations have COPD exacerbations or rather exacerbations of symptoms that mimic COPD. Interestingly, a recent investigation using Medicare-claim data from over 26 million inpatient admissions (of which 3.5% were COPD admissions) reported a 30-day COPD readmission rate of 20.2%.Citation2 Only half the readmitted COPD patients were admitted for respiratory-related illnesses, with COPD accountable for only 27.6% of readmissions. These data suggest that a subset of patients with COPD exacerbations may not get readmitted for COPD, and further emphasize the possibility of comorbidities playing an important role in recurrent hospitalizations in patients with COPD. Action plan-based self-management strategies are unlikely to be effective when the driving pathology of the exacerbation is indeed an undiagnosed comorbidity.

Phenotypes: asthma–COPD overlap syndrome

Finally, while phenotypic differentiation of asthma and COPD remains challenging, recent data have now well described an asthma–COPD overlap syndrome that may exist in nearly 20% of patients with obstructive lung disease.Citation72,Citation73 Unfortunately, this phenotype is thought to have increased disease severity and exacerbations than either condition alone.Citation74 It is likely that patients with this phenotype would have systematically been excluded from research investigations of asthma as well as COPD, further complicating extrapolation of existing data to this phenotype. Although not well understood, there has recently been an increasing recognition of a distinct phenotype with coexistence of upper lobe-dominant emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis, termed combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema.Citation75,Citation76 While our current understanding of clinically different phenotypes of COPD is growing,Citation77,Citation78 these patients may need stratified medicine and personalized care above and beyond simplistic self-management strategies.

Conclusion

COPD is a multisystem comorbid syndrome and the third-leading cause of death in the US. A transformational change to holistic strategies may be necessary to improve outcomes for this complex multisystem disease. While there is certainly a role for COPD action plan-based self-management strategies, the burden remains on the physician. An accurate diagnosis of COPD with objective confirmation of airflow obstruction is critical prior to consideration of any self-management. Identifying and addressing concomitant comorbidities cannot be overemphasized. Optimizing psychosocial well-being and mental health may be necessary for improving patient adherence and the success of any interventions. Strategies are more likely to be effective when the focus of care is patient-oriented (versus disease-oriented or COPD-specific). This may require a truly multidisciplinary approach. A well-structured integrated program may provide such a platform to improve outcomes in frequent exacerbators of COPD.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HalbertRJNatoliJLGanoABadamgaravEBuistASManninoDMGlobal burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysisEur Respir J200628352353216611654

- ShahTChurpekMMPerraillonMCKonetzkaRTUnderstanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansionChest201514751219122625539483

- PasqualeMKSunSXSongFHartnettHJStemkowskiSAImpact of exacerbations on health care cost and resource utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with chronic bronchitis from a predominantly Medicare populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012775776423152680

- MillerJDFosterTBoulangerLDirect costs of COPD in the U.S.: an analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) dataCOPD20052331131817146996

- CowieRLRevittSGUnderwoodMFFieldSKThe effect of a peak flow-based action plan in the prevention of exacerbations of asthmaChest19971126153415389404750

- No authors listedEffectiveness of routine self monitoring of peak flow in patients with asthmaBMJ199430869285645678148679

- ShearesBJMellinsRBDimangoEDo patients of subspecialist physicians benefit from written asthma action plans?Am J Respir Crit Care Med2015191121374138325867075

- NiewoehnerDEErblandMLDeupreeRHEffect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med1999340251941194710379017

- DaviesLAngusRMCalverleyPMOral corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomised controlled trialLancet1999354917745646010465169

- SelfTHPattersonSJHeadleyASFinchCKAction plans to reduce hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: focus on oral corticosteroidsCurr Med Res Opin201430122607261524926733

- BourbeauJJulienMMaltaisFReduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management interventionArch Intern Med2003163558559112622605

- RiceKLDewanNBloomfieldHEDisease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182789089620075385

- SridharMTaylorRDawsonSRobertsNJPartridgeMRA nurse led intermediate care package in patients who have been hospitalised with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax200863319420017901162

- EffingTKerstjensHvan der ValkPZielhuisGvan der PalenJ(Cost)-effectiveness of self-treatment of exacerbations on the severity of exacerbations in patients with COPD: the COPE II studyThorax2009641195696219736179

- FanVSGazianoJMLewRA comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med20121561067368322586006

- WoodsJAWheelerJSFinchCKPinnerNACorticosteroids in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014942143024833897

- LeuppiJDSchuetzPBingisserRShort-term vs conventional glucocorticoid therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the REDUCE randomized clinical trialJAMA2013309212223223123695200

- WaltersJATanDJWhiteCJWood-BakerRDifferent durations of corticosteroid therapy for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201412CD00689725491891

- de JongYPUilSMGrotjohanHPPostmaDSKerstjensHAvan den BergJWOral or IV prednisolone in the treatment of COPD exacerbations: a randomized, controlled, double-blind studyChest200713261741174717646228

- MaltaisFOstinelliJBourbeauJComparison of nebulized budesonide and oral prednisolone with placebo in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002165569870311874817

- AnthonisenNRManfredaJWarrenCPHershfieldESHardingGKNelsonNAAntibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med198710621962043492164

- AdamsSGMeloJLutherMAnzuetoAAntibiotics are associated with lower relapse rates in outpatients with acute exacerbations of COPDChest200011751345135210807821

- StockleyRAO’BrienCPyeAHillSLRelationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPDChest200011761638164510858396

- AllegraLBlasiFDianoPSputum color as a marker of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med200599674274715878491

- Brusse-KeizerMGGrotenhuisAJKerstjensHARelation of sputum colour to bacterial load in acute exacerbations of COPDRespir Med2009103460160619027281

- LlorCMoragasAHernandezSBayonaCMiravitllesMEfficacy of antibiotic therapy for acute exacerbations of mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186871672322923662

- MiravitllesMMoragasAHernandezSBayonaCLlorCIs it possible to identify exacerbations of mild to moderate COPD that do not require antibiotic treatment?Chest201314451571157723807094

- RoedeBMBresserPPrinsJMSchellevisFVerheijTJBindelsPJReduced risk of next exacerbation and mortality associated with antibiotic use in COPDEur Respir J200933228228819047316

- RohdeGWiethegeABorgIRespiratory viruses in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring hospitalisation: a case-control studyThorax2003581374212511718

- SeemungalTHarper-OwenRBhowmikARespiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116491618162311719299

- ZwerinkMBrusse-KeizerMvan der ValkPDSelf management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD00299024665053

- SedenoMFNaultDHamdDHBourbeauJA self-management education program including an action plan for acute COPD exacerbationsCOPD20096535235819863364

- JainVVAllisonRBeckSJImpact of an integrated disease management program in reducing exacerbations in patients with severe asthma and COPDRespir Med2014108121794180025294691

- BenzoRPKirschJLDuloheryMMAbascal-BoladoBEmotional intelligence: a novel outcome associated with wellbeing and self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Am Thorac Soc2016131101626501370

- BryantJMcDonaldVMBoyesASanson-FisherRPaulCMelvilleJImproving medication adherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewRespir Res20131410924138097

- LareauSCYawnBPImproving adherence with inhaler therapy in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010540140621191434

- KesslerRStahlEVogelmeierCPatient understanding, detection, and experience of COPD exacerbations: an observational, interview-based studyChest2006130113314216840393

- NgLWMackneyJJenkinsSHillKDoes exercise training change physical activity in people with COPD? A systematic review and meta-analysisChron Respir Dis201291172622194629

- Garcia-AymerichJPittaFPromoting regular physical activity in pulmonary rehabilitationClin Chest Med201435236336824874131

- BischoffEWHamdDHSedenoMEffects of written action plan adherence on COPD exacerbation recoveryThorax2011661263121037270

- BucknallCEMillerGLloydSMGlasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trialBMJ2012344e106022395923

- DiMatteoMRLepperHSCroghanTWDepression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherenceArch Intern Med2000160142101210710904452

- TuranOYemezBItilOThe effects of anxiety and depression symptoms on treatment adherence in COPD patientsPrim Health Care Res Dev201415324425123561004

- HanMKKimMGMardonRSpirometry utilization for COPD: how do we measure up?Chest2007132240340917550936

- JainVVAllisonDRAndrewsSMejiaJMillsPKPetersonMWMisdiagnosis among frequent exacerbators of clinically diagnosed asthma and COPD in absence of confirmation of airflow obstructionLung2015193450551225921015

- SokolKCSharmaGLinYLGoldblumRMChoosing wisely: adherence by physicians to recommended use of spirometry in the diagnosis and management of adult asthmaAm J Med2015128550250825554370

- AlbersMSchermerTMolemaJDo family physicians’ records fit guideline diagnosed COPD?Fam Pract2009262818719228813

- BednarekMMaciejewskiJWozniakMKucaPZielinskiJPrevalence, severity and underdiagnosis of COPD in the primary care settingThorax200863540240718234906

- MartinezCHManninoDMJaimesFAUndiagnosed obstructive lung disease in the United States: associated factors and long-term mortalityAnn Am Thorac Soc201512121788179526524488

- WaltersJAHansenECWaltersEHWood-BakerRUnder-diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study in primary careRespir Med2008102573874318222684

- GhattasCDaiAGemmelDJAwadMHOver diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in an underserved patient populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013854554924348030

- SchermerTRSmeeleIJThoonenBPCurrent clinical guideline definitions of airflow obstruction and COPD overdiagnosis in primary careEur Respir J200832494595218550607

- ZwarNAMarksGBHermizOPredictors of accuracy of diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practiceMed J Aust2011195416817121843115

- TinkelmanDGPriceDBNordykeRJHalbertRJMisdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and overJ Asthma2006431758016448970

- IzquierdoJLMartinAde LucasPRodriguez-Gonzalez-MoroJMAlmonacidCParavisiniAMisdiagnosis of patients receiving inhaled therapies in primary careInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010524124920714378

- CollinsBFRamenofskyDAuDHMaJUmanJEFeemsterLCThe association of weight with the detection of airflow obstruction and inhaled treatment among patients with a clinical diagnosis of COPDChest201414661513152024763942

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseBethesda (MD)GOLD2015 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed April 20, 2016

- HillasGPerlikosFTsiligianniITzanakisNManaging comorbidities in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015109510925609943

- SharafkhanehAPetersenNJYuHJDalalAAJohnsonMLHananiaNABurden of COPD in a government health care system: a retrospective observational study using data from the US Veterans Affairs populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010512513220461144

- SolerXGaioEPowellFLHigh prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Am Thorac Soc20151281219122525871443

- Tillie-LeblondIMarquetteCHPerezTPulmonary embolism in patients with unexplained exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and risk factorsAnn Intern Med2006144639039616549851

- RuttenFHCramerMJLammersJWGrobbeeDEHoesAWHeart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an ignored combination?Eur J Heart Fail20068770671116531114

- CaminatiACavazzaASverzellatiNHarariSAn integrated approach in the diagnosis of smoking-related interstitial lung diseasesEur Respir Rev20122112520721722941885

- MargaritopoulosGAVasarmidiEJacobJWellsAUAntoniouKMSmoking and interstitial lung diseasesEur Respir Rev20152413742843526324804

- WalshSLNairADesaiSRInterstitial lung disease related to smoking: imaging considerationsCurr Opin Pulm Med201521440741625978626

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- XuWColletJPShapiroSIndependent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178991392018755925

- JenningsJHDigiovineBObeidDFrankCThe association between depressive symptoms and acute exacerbations of COPDLung2009187212813519198940

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- Paz-DiazHMontes de OcaMLopezJMCelliBRPulmonary rehabilitation improves depression, anxiety, dyspnea and health status in patients with COPDAm J Phys Med Rehabil2007861303617304686

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJPrevalence of sub-threshold depression in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200318541241612766917

- PostmaDSReddelHKten HackenNHvan den BergeMAsthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: similarities and differencesClin Chest Med201435114315624507842

- SorianoJBDavisKJColemanBVisickGManninoDPrideNBThe proportional Venn diagram of obstructive lung disease: two approximations from the United States and the United KingdomChest2003124247448112907531

- MenezesAMMontes de OcaMPerez-PadillaRIncreased risk of exacerbation and hospitalization in subjects with an overlap phenotype: COPD-asthmaChest2014145229730424114498

- CottinVCordierJFCombined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: an experimental and clinically relevant phenotypeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172121605 author reply 1605–160616339012

- JankowichMDRoundsSICombined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a reviewChest2012141122223122215830

- AgustiAPhenotypes and disease characterization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: toward the extinction of phenotypes?Ann Am Thorac Soc201310SupplS125S13024313762

- BurgelPRSethiSKimVChronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: past, present, and futureAnn Am Thorac Soc201512328929025786144