Abstract

Background

Statins have been recommended for the use in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, but different statins have distinct pharmacological characteristics. This multi-treatment meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy of seven statins in the secondary prevention of major cerebrovascular events (CVEs).

Methods and analyses

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched to identify studies published between January 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016. The included randomized controlled trials investigated the efficacy of lovastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, simvastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin or rosuvastatin in the secondary prevention of CVEs. The primary outcomes were CVEs; the secondary outcomes were all-cause death, fatal stroke and nonfatal stroke. Meta-analysis and network meta-analysis were used for data synthesis.

Results

A total of 42 studies with 82,601 patients were included for analysis. In the secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, the major CVEs in pravastatin (risk ratio [RR] 0.87, 0.76–0.99)- and atorvastatin (RR 0.59, 0.49–0.72)-treated patients reduced significantly compared with controls. Indirect comparisons with network meta-analysis showed that RR was 0.60 (0.40–0.92) for atorvastatin compared with rosuvastatin. Compared to controls, the all-cause death was reduced by 12% in statins-treated patients (RR 0.88, 0.81–0.96). Indirect comparisons with network analysis showed a significant difference in the nonfatal stroke between fluvastatin-treated patients and lovastatin-treated patients (RR 0.28, 0.07–0.95).

Conclusion

Different statins have distinct pharmacological characteristics, and there are differences in statistical and clinical outcomes among several statins.

Introduction

In the past century, the disease profile changed significantly worldwide. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) accounted for 1/10 of causes of death in early 1900s, but it has been the leading cause of death worldwide so far, accounting for one-third of causes of death. The prevalence of ASCVD increases with age. In addition, its prevalence further elevates in late life with the reduced mortality related to infection and malnutrition. Thus, ASCVD is affecting the decision making of world public health policy. Ischemic stroke is one of the most important clinical types of ASCVD and has a high recurrence rate. The ischemic stroke-related neurological impairment and subsequent emotional dysfunction and social dysfunction bring a great burden to the society and the families of these patients. Currently, controlling the serum lipid marker (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C]) is crucial to reduce the recurrence rate of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or ischemic stroke.Citation1

To date, statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor) have been widely used in the lipid-lowering therapy. On the basis of findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), statins have been a major strategy in reducing the risk for ASCVD.Citation2 Several clinical trials have shown that statins can significantly reduce serum LDL-C and effectively decrease the risk for stroke.Citation3 Statins can reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular events, and thus, they have been recommended for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5 In addition, there is evidence showing that high-dose statins are better to reduce the risk for stroke compared to standard-dose statins.Citation6 However, there is still controversy on the clinical effects of different statins on the outcomes of ASCVD. A study indirectly compared influence of atorvastatin, pravastatin and simvastatin on the cerebrovascular events (CVEs), but it was a placebo-control study with a small sample size and there were active comparator trials in this study.Citation7 The network meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the RCT that investigated the effects of primary and secondary prevention with atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin or simvastatin in CVD patients, but it excluded head–head evaluation of different statins. Although another network meta-analysis used head–head evaluation, but pitavastatin was not investigated.Citation8 Moreover, the incidence of cerebrovascular diseases was not a primary outcome in previous head–head network meta-analysis.Citation9–Citation12

Different statins have distinct pharmacological characteristics. As the number of patients in need for statin therapy continues to increase, information regarding the relative efficacy of statins is needed for better decision making. Meta-analysis with a large amount of updated data may provide true and strict clinical evaluation and accurately assess the therapeutic efficacy. This meta-analysis aimed to systemically evaluate the efficacy of statins in clinical studies that were conducted between statins-treated patients and routine controls or placebo controls and different statin-treated patients. In addition, the role of different statins in the secondary prevention of major CVEs was evaluated in patients with cardiovascular diseases.

Methods and analyses

Systematic review methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify studies published between January 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016. We identified the studies prior to January 2011 from the bibliography of previously published systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. We used the search terms “lovastatin”, “atorvastatin”, “fluvastatin”, “simvastatin”, “pitavastatin”, “pravastatin”, “rosuvastatin”, “cardiovascular disease” and “HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors/therapeutic use”. Two reviewers (PZ and DW) independently performed abstract, title and full-text screening and entered data into a data extraction form. A third reviewer (YW) approved the study selection.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) open and double-blind RCTs were included; 2) head–head studies or those with placebo, diet or routine therapy as a control were included; 3) patients had cardiovascular diseases; 4) the number of patients was >60; 5) atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin or simvastatin was used for >4 weeks and 6) the primary outcomes were major CVEs, and the secondary outcomes were all-cause death, fatal stroke and nonfatal stroke. The major CVEs in this study included fatal stroke, nonfatal stroke and TIA; the nonfatal stroke did not include TIA. In addition, clinical studies in which there were patients with renal dysfunction were excluded. The study characteristics, including methods, participants, interventions and outcomes, were extracted from each study (Supplementary material).

Statistical analysis

To summarize all available evidence, we conducted both direct and network meta-analyses. First, we did traditional pairwise meta-analysis for direct comparisons between two treatment arms by Review Manager 5.1. In the conventional direct meta-analysis, two or more studies that compared two interventions of interest were statistically combined. We calculated the pooled risk ratio (RR) with a 95% CI. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics. For the Q statistic, a P-value >0.10 and for the χ2 test and for the I2 statistic, an I2 value <25% were interpreted as low-level heterogeneity. A pooled effect was calculated with a fixed-effect model when there was no statistically significant heterogeneity; otherwise, a random-effect model was used.

A network meta-analysis was conducted using a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo method and fitted in R package. Analytical results are presented as RR with 95% credible intervals (CrIs). The RR was estimated using the median of the posterior distribution, and 95% CrIs were obtained based on the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the posterior distribution, which can be interpreted in the same way as conventional 95% CIs. Rankings for the treatment efficacy of the interventions were originally derived from Monte Carlo simulations and presented as the probability of possessing a specific ranking; the probabilities of different rankings of the same treatment were summed to 100%. Pooled results were considered as statistically significant for P<0.05 or if the 95% CI (CrI) did not contain the value 1. In this study, the patient samples from different statins were weighted in both pairwise meta-analysis and network meta-analysis.

Results

General data

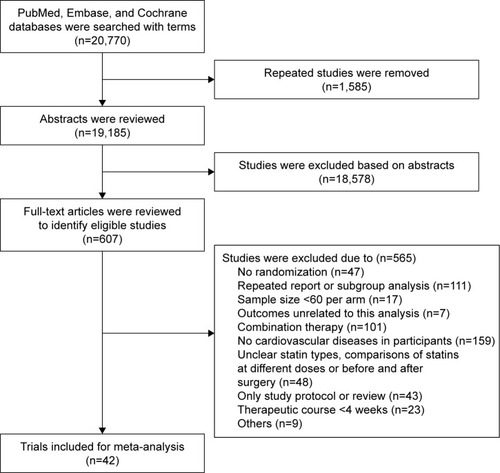

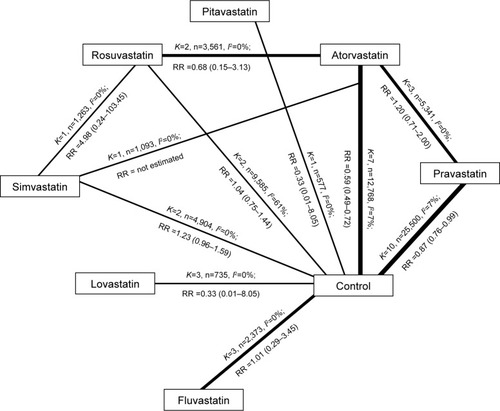

A total of 20,770 studies potentially related to the topic were identified, of which 607 studies were included for final analysis and 20,163 unrelated studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (). In addition, 42 clinical trials published between 1994 and 2016 were included for network meta-analysis. The general information of these studies is presented in . In the studies included for network meta-analysis, 82,601 subjects received treatment with one of seven statins and 24.1% subjects were female. Of these studies, treatment with one statin was compared with control (placebo treatment, routine treatment or diet treatment) in 32 studies. Of these 32 studies, pravastatin was evaluated in 13 studies,Citation13–Citation25 atorvastatin in seven,Citation26–Citation32 lovastatin in three,Citation33–Citation35 simvastatin in three,Citation36–Citation38 fluvastatin in three,Citation39–Citation41 rosuvastatin in twoCitation42,Citation43 and pitavastatin in one.Citation44 In 10 studies, the treatment with one statin was compared with therapy of another statin.Citation45–Citation54 In these 10 studies, a statin was used at two doses in one study,Citation54 the head–head study of atorvastatin and pravastatin was found in four studies,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation51 head–head study of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin was found in three studiesCitation49,Citation50,Citation54 (rosuvastatin at two doses was used in one study), head–head study of atorvastatin and simvastatin was found in two studiesCitation52,Citation53 and head–head study of rosuvastatin and simvastatin was found in one study.Citation47 The follow-up period ranged from 143 weeks to 317 weeks. In five studies, the follow-up period was <24 weeks. shows the meta-analysis of seven statins in the prevention of major CVEs.

Figure 2 Meta-analysis of seven statins in the prevention of major CVEs.

Abbreviations: CVE, cerebrovascular event; RR, risk ratio.

Table 1 Characteristics of studies included

Comparative benefits of statins on major CVEs: findings of the multiple-treatment meta-analyses

In 32 studies comparing statins treatment and control treatment, major CVEs were reported in 27 studiesCitation13–Citation15,Citation18–Citation23,Citation25–Citation32,Citation34–Citation36,Citation38–Citation44 in which there were 66,007 patients and a total of 2,057 major CVEs. In the secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, results showed that pravastatin and atorvastatin could reduce the incidence of major CVEs by 13% and 41%, respectively, compared with the control group, but there was no significant difference between other statins and control (). In 10 head–head studies,Citation45–Citation54 the influence of statins on the major CVEs was reported in seven studies,Citation45,Citation47–Citation52 in which there were 9,565 patients and a total of 69 major CVEs. Paired comparison in network meta-analysis showed a significant difference only between atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (RR 1.7,1.10–2.50).

Table 2 Network meta-analysis of prevention of major CVEs: direction comparisons between statin treatment and control treatment as well as different statin treatments

Comparative benefits of statins on all-cause mortality: findings of the multiple-treatment meta-analyses

The all-cause death was investigated in 40 studies,Citation13–Citation20,Citation22–Citation49,Citation51–Citation54 in which there were 76,483 patients and 7,328 deaths. Of included studies, statin treatment was compared with control treatment in 31 studies, in which there were 6,391 deaths occurring in 57,354 patients; comparison between two statin treatments was found in 10 studies,Citation42,Citation45–Citation49,Citation51–Citation54 in which there were 937 deaths occurring in 19,133 patients. Direct meta-analysis showed that the mortality of any cause in statin-treated patients was reduced by 12% compared to the control group (RR 0.88, 0.81–0.96), and a significant difference was only noted between the pravastatin group and the control group (RR 0.84, 0.76–0.94). Comparison between two treatments showed significant difference between pravastatin and atorvastatin (RR 1.60, 1.17–2.19), but network meta-analysis showed a marked difference only between fluvastatin and lovastatin (RR 3.60, 1.10–14.00; ).

Table 3 Network meta-analysis of prevention of major CVEs and death of any cause with seven different statins

Comparative benefits of statins on nonfatal and fatal strokes: findings of the multiple-treatment meta-analyses

Of the studies on pitavastatin, fatal stroke had never been reported. In 19 studies with 41,144 patients,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17–Citation20,Citation23,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation34,Citation36,Citation39,Citation41–Citation43,Citation48,Citation52 the fatal stroke was reported in 323 patients. In 26 studies,Citation14,Citation18–Citation23,Citation25–Citation28,Citation31,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation42–Citation45,Citation47–Citation51 nonfatal stroke was reported as an outcome, and it was found in 1,529 patients among 49,710 patients included in these studies. Direct meta-analysis showed no significant difference between statin treatment and control treatment as well as between two statin treatments. summarizes the results of network meta-analysis of fatal stroke and nonfatal stroke. Our results showed that significant difference was observed in the nonfatal stroke only between atorvastatin and simvastatin (RR 1.9, 1.1–3.7).

Table 4 Network meta-analysis of prevention of fatal stroke and nonfatal stroke with seven different statins

Discussion

This meta-analysis was based on 42 studies in which a total of 82,601 subjects randomly received treatment with seven different statins. Statistical and clinical differences were found in several statins. Our results showed that, in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, the mortality of any cause was reduced by 12% after statin treatment compared to the control treatment; the incidence of major CVEs was reduced by 13% and 41% after treatment with pravastatin and atorvastatin, respectively, compared with the control treatment. Indirect comparison with network meta-analysis showed that rosuvastatin was better than atorvastatin in the prevention of major CVEs and fluvastatin was better than lovastatin in the prevention of nonfatal stroke when statins were used in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases.

Statins have pleiotropic effects, including the lipid- lowering, vasodilation, anti-thrombotic, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects.Citation55–Citation62 Animal experiments and clinical studies have shown that statins may exert neuroprotective effects after acute cerebral infarction.Citation63–Citation65 Our results further confirmed and expanded previous results from meta-analysis. Clinical guideline recommends the use of statins in the secondary prevention of noncardiac stroke.Citation66 To reduce LDL-C has been one of important strategies in the clinical prevention of cardiovascular events, and undoubtedly statins, are the most effective drugs used to reduce LDL-C. Statins may competitively inhibit hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, which is a rate-limiting enzyme in the endogenous cholesterol synthesis, and then block the metabolism of intracellular hydroxymaleic acid and reduce the endogenous production of cholesterol, exerting lipid-lowering effect. Although different statins have the identical mechanism in their lipid-lowering effect, the difference in the chemical structure among these statins makes their physical characteristics and internal pharmacokinetics different. SPARCL was the only one study that investigated the influence of statins used for secondary prevention on the TIA and stroke,Citation26 but we could not expand their results to the use of other statins. In this study, meta-analysis was conducted in the population with cardiovascular diseases who were medicated with statins for the secondary prevention, and results showed difference among several statins. Probably, the actual difference among other statins might not be identified by this meta-analysis.

In this study, the majority of clinical trials included did not fully report the information about the randomization and allocation concealment, which may compromise the overall validity. Of note, the studies on different statins had similarities on the study design and implementation, and the lack of information about the quality assessment might be ascribed to the manuscript drafting but not to the actual defect in study design as shown in other systemic reviews.Citation67 In our study, new network meta-analysis was used, and placebo-controlled and active comparator trials were merged to investigate the head–head studies of statins. Our study was different from previous network analysis: 1) not only placebo-controlled trials but also active comparator trials were included for analysis; 2) our study was an update of previous studies, and studies investigating seven commercially available statins (cerivastatin is not commercially available due to adverse effects) were included for analysis, which was not found in previous meta-analysis of stroke and 3) in this study, the major CVEs served as the main outcomes, but cardiovascular events were used as main outcomes in previous meta-analyses.

There were limitations in this study. First, this was a meta-analysis based on previous studies, and the number of studies included was limited. Only a few prospective, head–head clinical trials with clinical outcome were identified in the available studies. Second, the meta-analysis based on the data from published studies was limited by the quality of these studies. For example, the included studies that reported major CVEs might not report the fatal stroke. Third, there was a difference in the results of direct and indirect analyses, but direct comparison would make the results be more likely to be true. This difference might be related to the small sample size and the conservative nature of the Bayesian hierarchical random-effects model.

Conclusion

Different statins have distinct pharmacological characteristics and there are differences of statistical and clinical outcome among several statins.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KernanWNOvbiageleBBlackHRGuidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke AssociationStroke2014457 2160 223624788967

- FinkelJBDuffyD2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guideline: paradigm shifts in managing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease riskTrends Cardiovasc Med2015254 340 34725435519

- AmarencoPLabreucheJLipid management in the prevention of stroke: review and updated meta-analysis of statins for stroke preventionLancet Neurol200985 453 46319375663

- European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive CommitteeESO Writing CommitteeGuidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008Cerebrovasc Dis2008255 457 50718477843

- Chinese Society of Neurology, Neurology Cerebrovascular Group2014 Guideline of the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in ChinaChin J Neurol2015484 258 273

- CannonCPSteinbergBAMurphySAMegaJLBraunwaldEMeta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapyJ Am Coll Cardiol2006483 438 44516875966

- ZhouZRahmeEPiloteLAre statins created equal? Evidence from randomized trials of pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin for cardiovascular disease preventionAm Heart J20061512 273 28116442888

- NaciHBrugtsJJFleurenceRAdesAEComparative effects of statins on major cerebrovascular events: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis of placebo-controlled and active-comparator trialsQJM20131064 299 30623431221

- AlbertonMWuPDruytsEBrielMMillsEJAdverse events associated with individual statin treatments for cardiovascular disease: an indirect comparison meta-analysisQJM20121052 145 15721920996

- MillsEJRachlisBWuPDevereauxPJAroraPPerriDPrimary prevention of cardiovascular mortality and events with statin treatments: a network meta-analysis involving more than 65,000 patientsJ Am Coll Cardiol20085222 1769 178119022156

- MillsEJWuPChongGEfficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trialsQJM20111042 109 12420934984

- RibeiroRAZiegelmannPKDuncanBBImpact of statin dose on major cardiovascular events: a mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis involving more than 175,000 patientsInt J Cardiol20131662 431 43922192281

- The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study GroupPrevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levelsN Engl J Med199833919 1349 13579841303

- Results of the low-dose (20 mg) pravastatin GISSI Prevenzione trial in 4271 patients with recent myocardial infarction: do stopped trials contribute to overall knowledge? GISSI Prevenzione Investigators (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico)Ital Heart J2000112 810 82011302109

- BertrandMEMcFaddenEPFruchartJCEffect of pravastatin on angiographic restenosis after coronary balloon angioplasty. The PREDICT Trial Investigators. Prevention of restenosis by elisor after transluminal coronary angioplastyJ Am Coll Cardiol1997304 863 8699316510

- CrouseJR3rdByingtonRPBondMGPravastatin, lipids, and atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries (PLAC-II)Am J Cardiol1995757 455 4597863988

- JukemaJWBruschkeAVvan BovenAJEffects of lipid lowering by pravastatin on progression and regression of coronary artery disease in symptomatic men with normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol levels. The Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS)Circulation19959110 2528 25407743614

- MakuuchiHFuruseAEndoMEffect of pravastatin on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients after coronary artery bypass surgeryCirc J2005696 636 64315914938

- NakagawaTKobayashiTAwataNRandomized, controlled trial of secondary prevention of coronary sclerosis in normocholesterolemic patients using pravastatin: final 5-year angiographic follow-up of the Prevention of Coronary Sclerosis (PCS) studyInt J Cardiol2004971 107 11415336816

- PittBManciniGBEllisSGRosmanHSParkJSMcGovernMEPravastatin limitation of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries (PLAC I): reduction in atherosclerosis progression and clinical events. PLAC I investigationJ Am Coll Cardiol1995265 1133 11397594023

- SacksFMPfefferMAMoyeLAThe effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigatorsN Engl J Med199633514 1001 10098801446

- SatoHKinjoKItoHEffect of early use of low-dose pravastatin on major adverse cardiac events in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the OACIS-LIPID StudyCirc J2008721 17 2218159093

- ShepherdJBlauwGJMurphyMBPravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trialLancet20023609346 1623 163012457784

- ThompsonPLMeredithIAmerenaJCampbellTJSlomanJGHarrisPJEffect of pravastatin compared with placebo initiated within 24 hours of onset of acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina: the Pravastatin in Acute Coronary Treatment (PACT) trialAm Heart J20041481 e215215811

- YokoiHNobuyoshiMMitsudoKKawaguchiAYamamotoAATHEROMA Study InvestigatorsThree-year follow-up results of angiographic intervention trial using an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor to evaluate retardation of obstructive multiple atheroma (ATHEROMA) studyCirc J2005698 875 88316041153

- AmarencoPBogousslavskyJCallahanA3rdHigh-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attackN Engl J Med20063556 549 55916899775

- AthyrosVGKakafikaAIPapageorgiouAAEffects of statin treatment in men and women with stable coronary heart disease: a subgroup analysis of the GREACE StudyCurr Med Res Opin2008246 1593 159918430270

- BaeJHBassengeEKimKYSynnYCParkKRSchwemmerMEffects of low-dose atorvastatin on vascular responses in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stentingJ Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther200493 185 19215378139

- KnoppRHd’EmdenMSmildeJGPocockSJEfficacy and safety of atorvastatin in the prevention of cardiovascular end points in subjects with type 2 diabetes: the Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Endpoints in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (ASPEN)Diabetes Care2006297 1478 148516801565

- KorenMJHunninghakeDBClinical outcomes in managed-care patients with coronary heart disease treated aggressively in lipid-lowering disease management clinics: the alliance studyJ Am Coll Cardiol2004449 1772 177915519006

- SchwartzGGOlssonAGEzekowitzMDEffects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trialJAMA200128513 1711 171811277825

- StonePHLloyd-JonesDMKinlaySEffect of intensive lipid lowering, with or without antioxidant vitamins, compared with moderate lipid lowering on myocardial ischemia in patients with stable coronary artery disease: the vascular basis for the treatment of Myocardial Ischemia StudyCirculation200511114 1747 175515809368

- BlankenhornDHAzenSPKramschDMCoronary angiographic changes with lovastatin therapy. The Monitored Atherosclerosis Regression Study (MARS)Ann Intern Med199311910 969 9768214993

- WatersDHigginsonLGladstonePEffects of monotherapy with an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis as assessed by serial quantitative arteriography. The Canadian Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention TrialCirculation1994893 959 9688124836

- WeintraubWSBoccuzziSJKleinJLLack of effect of lovastatin on restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Lovastatin Restenosis Trial Study GroupN Engl J Med199433120 1331 13377935702

- Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S)Lancet19943448934 1383 13897968073

- Effect of simvastatin on coronary atheroma: the Multicentre Anti-Atheroma Study (MAAS)Lancet19943448923 633 6387864934

- TeoKKBurtonJRBullerCELong-term effects of cholesterol lowering and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on coronary atherosclerosis: the Simvastatin/Enalapril Coronary Atherosclerosis Trial (SCAT)Circulation200010215 1748 175411023927

- LiemAHvan BovenAJVeegerNJEffect of fluvastatin on ischaemia following acute myocardial infarction: a randomized trialEur Heart J20022324 1931 193712473255

- OstadalPAlanDVejvodaJFluvastatin in the first-line therapy of acute coronary syndrome: results of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (the FACS-trial)Trials201011 6120500832

- SerruysPWde FeyterPMacayaCFluvastatin for prevention of cardiac events following successful first percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trialJAMA200228724 3215 322212076217

- KjekshusJApetreiEBarriosVRosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failureN Engl J Med200735722 2248 226117984166

- TavazziLMaggioniAPMarchioliREffect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet20083729645 1231 123918757089

- TakanoHMizumaHKuwabaraYEffects of pitavastatin in Japanese patients with chronic heart failure: the Pitavastatin Heart Failure Study (PEARL Study)Circ J2013774 917 92523502990

- CannonCPBraunwaldEMcCabeCHIntensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromesN Engl J Med200435015 1495 150415007110

- DeedwaniaPStonePHBairey MerzCNEffects of intensive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy on myocardial ischemia in older patients with coronary heart disease: results of the Study Assessing Goals in the Elderly (SAGE)Circulation20071156 700 70717283260

- HallASJacksonBMFarrinAJA randomized, controlled trial of simvastatin versus rosuvastatin in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Secondary Prevention of Acute Coronary Events – Reduction of Cholesterol to Key European Targets TrialEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil2009166 712 72119745745

- IzawaAKashimaYMiuraTAssessment of lipophilic vs. hydrophilic statin therapy in acute myocardial infarction – ALPS-AMI studyCirc J2015791 161 16825392071

- LablancheJMLeoneAMerkelyBComparison of the efficacy of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in reducing apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A-1 ratio in patients with acute coronary syndrome: results of the CENTAURUS studyArch Cardiovasc Dis20101033 160 16920417447

- NichollsSJBallantyneCMBarterPJEffect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary diseaseN Engl J Med201136522 2078 208722085316

- NissenSETuzcuEMSchoenhagenPEffect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trialJAMA20042919 1071 108014996776

- OlssonAGErikssonMJohnsonOA 52-week, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, double-blind, double-dummy study to assess the efficacy of atorvastatin and simvastatin in reaching low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride targets: the treat-to-target (3T) studyClin Ther2003251 119 13812637115

- PedersenTRFaergemanOKasteleinJJHigh-dose atorvastatin vs usual-dose simvastatin for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction: the IDEAL study: a randomized controlled trialJAMA200529419 2437 244516287954

- PittBLoscalzoJMonyakJMillerERaichlenJComparison of lipid-modifying efficacy of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in patients with acute coronary syndrome (from the LUNAR study)Am J Cardiol20121099 1239 124622360820

- Amin-HanjaniSStaglianoNEYamadaMHuangPLLiaoJKMoskowitzMAMevastatin, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, reduces stroke damage and upregulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase in miceStroke2001324 980 98611283400

- AsahiMHuangZThomasSProtective effects of statins involving both eNOS and tPA in focal cerebral ischemiaJ Cereb Blood Flow Metab2005256 722 72915716855

- ChenJZhangZGLiYStatins induce angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis after strokeAnn Neurol2003536 743 75112783420

- Di NapoliPTaccardiAAOliverMDe CaterinaRStatins and stroke: evidence for cholesterol-independent effectsEur Heart J20022324 1908 192112473253

- EndresMLaufsUHuangZStroke protection by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibitors mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthaseProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19989515 8880 88859671773

- KawashimaSYamashitaTMiwaYHMG-CoA reductase inhibitor has protective effects against stroke events in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive ratsStroke2003341 157 16312511768

- SironiLCiminoMGuerriniUTreatment with statins after induction of focal ischemia in rats reduces the extent of brain damageArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol2003232 322 32712588778

- VaughanCJDelantyNNeuroprotective properties of statins in cerebral ischemia and strokeStroke1999309 1969 197310471452

- ElkindMSFlintACSciaccaRRSaccoRLLipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortalityNeurology2005652 253 25816043795

- HassanYAl-JabiSWAzizNALooiIZyoudSHStatin use prior to ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased in-hospital mortalityFundam Clin Pharmacol2011253 388 39420608996

- Marti-FabregasJGomisMArboixAFavorable outcome of ischemic stroke in patients pretreated with statinsStroke2004355 1117 112115073403

- SaccoRLAdamsRAlbersGGuidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guidelineCirculation200611310 e409 e44916534023

- Huwiler-MuntenerKJuniPJunkerCEggerMQuality of reporting of randomized trials as a measure of methodologic qualityJAMA200228721 2801 280412038917