Abstract

Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, an incurable, progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease, suffer an impaired quality of life due to symptoms, resultant functional limitations, and the constraints of supplemental oxygen. Two antifibrotic medications, nintedanib and pirfenidone, are approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Both medications slow the rate of decline of lung function, but their effect on patient-reported outcomes is not yet fully understood. Nintedanib may slow the decline in health-related quality of life for treated patients. Pirfenidone may slow the progression of dyspnea and improve cough. Patients and providers should participate in shared decision-making when starting antifibrotic therapy, taking into consideration the benefits of treatment in addition to drug-related side effects and dosing schedules. Although antifibrotic therapy may have an impact on health-related quality of life, providers should also focus on comprehensive care of the patient to improve health-related outcomes. This includes a multidisciplinary evaluation, diagnosis and treatment of comorbid medical conditions, and referral to and participation in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, incurable fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD). IPF is a disease of advancing age, with most patients presenting during the sixth and seventh decades of life. Although exactly what causes IPF is unknown, repetitive alveolar epithelial injury leading to fibrosis in a genetically susceptible individual is likely.Citation1 Risk factors for the disease include cigarette smoking, other environmental inhalational exposures, and chronic microaspiration secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease.Citation1 The diagnosis of IPF is made based on a combination of suggestive clinical history and a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan. Some cases may require surgical lung biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.Citation2 The clinical course for patients with IPF is heterogeneous, with some experiencing periods of relative stability and others having a more rapid decline in lung function. The overall median survival for patients with IPF is 3–5 years.Citation3

Clinically, as fibrosis advances and further alters the normal pulmonary physiology, affected patients experience a high burden of symptoms. Progressive activity-limiting dyspnea is the hallmark symptom of IPF and leads to significantly impaired physical functioning. Patients also commonly experience nonproductive cough and fatigue. Due to symptoms and the resultant impact on physical, social, and emotional well-being, patients with IPF suffer from decreased health-related quality of life (HRQL).Citation4,Citation5

HRQL refers to a patient’s satisfaction with aspects of life that are impacted by health or disease.Citation6 Measuring HRQL has been described as the “quantification” of the impact of health or disease on a person’s life.Citation7 It can be measured using validated questionnaires that are either generic or disease specific. In IPF research, questionnaires commonly used to measure HRQL include the following: the 36-Item Short Form Questionnaire, a generic HRQL questionnaire; St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), an obstructive lung disease-specific HRQL tool that has been widely used in studies of IPF patients;Citation8–Citation11 Living with IPF or A Tool to Assess Quality of Life in IPF, both IPF-specific HRQL questionnaires;Citation12–Citation14 and the King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease health status questionnaire, an ILD-specific questionnaire with validity for use in IPF.Citation15,Citation16

Choosing the appropriate tool is dependent on the population and question of interest for a given study. Regardless of the questionnaire used, measuring HRQL is critically important to understanding the impact of disease on patients’ everyday lives. It is also a quantifiable and reproducible measurement that can be used in clinical trials to assess the impact of emerging therapeutics on outcomes that are, arguably, most meaningful to patients.

In October 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved two antifibrotic medications – nintedanib and pirfenidone – for the treatment of IPF. In multiple randomized, controlled clinical trials, both drugs slowed the rate of decline in lung function in treated patients.Citation17–Citation20 Over time, this may lead to improved survival. The impact of these medications on patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including symptoms and HRQL, is not yet fully known. Here we review these medications, summarize the literature with respect to PROs and novel antifibrotics, and discuss additional strategies to improve HRQL for patients with IPF.

Nintedanib

Nintedanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that prevents proliferation, migration, and transformation of fibroblasts by targeting upstream receptors important for the development of fibrosis. Specifically, nintedanib competitively blocks the binding sites of platelet-derived growth factor receptor, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and fibroblast growth factor receptor.Citation21 Additionally, it may have pleiotropic effects on profibrotic cytokines.

Nintedanib was approved for use in IPF as a result of one Phase II clinical trial (To Improve Pulmonary Fibrosis with BIBF 1120, TOMORROW)Citation22 and two Phase III clinical trials (Investigating the Safety and Efficacy of Nintedanib in IPF, INPULSIS 1 and 2).Citation17 Compared with placebo, treatment with nintedanib 150 mg twice daily demonstrated a significant decrease in the rate of decline of lung function as measured by forced vital capacity (FVC).Citation17 In pooled analysis of data from the TOMORROW and INPULSIS 1 and 2 trials, the annual rate of decline of FVC was 110.9 mL/year less in the treatment group when compared with placebo (95% CI: [78.5, 143.3]; P<0.0001). Furthermore, treated patients had greater time to an acute exacerbation and a reduction in both all-cause and respiratory-specific mortality at 52 weeks.Citation23

Despite achieving these clinically meaningful endpoints, the impact of nintedanib on symptoms and HRQL is not as well understood. In the TOMORROW and INPULSIS studies, HRQL was assessed using the SGRQ. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse quality of life. In prior studies, the minimal important difference (MID) – the smallest difference in score on a measure that patients experience as a change in clinical status – of the total SGRQ score in IPF is seven points.Citation10

In the TOMORROW and INPULSIS studies, the total SGRQ score increased at 52 weeks (suggesting deterioration in HRQL) for both the treatment and placebo arms (by 2.92 and 4.97 points, respectively). This between-group difference of –2.05 points was statistically significant (95% CI: [−3.59,−0.50]; P=0.0095),Citation23 suggesting less decline in HRQL in the treatment group. However, as neither group changed by the MID, inferences regarding the impact of treatment on HRQL are difficult to assess. This relatively smaller change in SGRQ may indicate a slower rate of decline in HRQL for patients treated with nintedanib, but it did not improve HRQL.

For some practitioners, there is concern that treatment with nintedanib may impair HRQL due to side effects. The most commonly reported side effects are gastrointestinal (GI) including diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Diarrhea affected over 60% of patients treated with nintedanib when compared with approximately 18% in the placebo arm. Diarrhea is typically limited to the first 3 months of therapy and can be managed with dose reduction and antimotility agents. Due to effective alternative management strategies, only 5% of treated patients discontinued the drug as a result of diarrhea.Citation23 Additional side effects included elevated liver enzymes and weight loss secondary to GI side effects. It is recommended to monitor liver enzymes at initiation, monthly for the first 3 months, and every 3 months thereafter. The effect of nintedanib on extrapulmonary HRQL is unknown.

Pirfenidone

Pirfenidone has been shown to have antiinflammatory and antifibrotic properties, but the exact mechanism of action in IPF is not completely understood. Pirfenidone suppresses the activity of multiple proinflammatory cytokines and TNF-α, and similar to nintedanib, inhibits TGF-β with downstream reduction of fibroblast proliferation.Citation24

Pirfenidone was approved for use in IPF after results from the CAPACITY (Pirfenidone in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, I and II)Citation20 and ASCEND (A Phase III Trial of Pirfenidone in Patients with Pulmonary Fibrosis)Citation18 trials demonstrated a significantly slower decline in FVC when compared with placebo at 1 year. Pooled analysis of the CAPACITY and ASCEND trials demonstrated a mean between-group difference in rate of FVC decline of 148 mL/year less in the treatment group (P<0.001).Citation25 Furthermore, treatment with pirfenidone when compared with placebo reduced the incidence of all-cause mortality at 1 year by 48%, improved progression-free survival,Citation25 and lowered the risk of respiratory-related hospitalizations.Citation26 Importantly, given the variable clinical course of IPF, patients who remained on pirfenidone therapy, even after evidence of disease progression, had a slower subsequent rate of lung function decline when compared with placebo.Citation27

The impact of pirfenidone on HRQL was not directly measured in either the CAPACITY or ASCEND trials. However, dyspnea scores were collected using the University of California San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (UCSD-SOBQ).Citation28 The UCSD-SOBQ is a 24-item questionnaire used to assess self-perceived levels of dyspnea while performing various physical activities and how much dyspnea or fear of dyspnea limits patients in their everyday lives. Higher scores indicate greater levels of dyspnea.

In pooled analysis, both the treatment and placebo arms had increased UCSD-SOBQ scores at 1 year when compared with baseline. However, fewer patients in the pirfenidone group (24.0%) when compared with placebo (31.4%)Citation25 had an increase in greater than 20 points at 1 year (MID for UCSD-SOBQ=8 points in IPF). Although the UCSD-SOBQ is not a quality of life-specific measure, it does quantify dyspnea, which is the primary driver of impaired quality of life in IPF.Citation29 Therefore, if treatment slows the rate of decline in dyspnea as evidenced by a smaller increase in UCSD-SOBQ score, this may translate into a meaningful benefit for HRQL. Importantly, however, the treatment group did not have an improvement in their dyspnea scores – dyspnea still worsened over the study period for both groups.

In addition to a possible impact on dyspnea scores, pirfenidone has recently been associated with improvements in cough severity in a small, multicenter observational study.Citation30 Patients treated with pirfenidone showed improvements in both objective cough counts and patient-reported cough severity at 12 weeks. Although pirfenidone has not been shown to directly improve HRQL, improving symptoms is an alternative mechanism to impact HRQL for patients with IPF.

Similar to nintedanib, there are known side effects to treatment with pirfenidone that may impact HRQL. Pirfenidone is associated with GI side effects including nausea, appetite suppression, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting. Taking the medication with meals or a dose reduction strategy helps to ameliorate some of the GI side effects that patients experience. Skin rash is another commonly reported side effect of pirfenidone. Patients should avoid or minimize sun exposure and use sun-protection including sunblock and protective clothing. Liver function elevations may also be seen with pirfenidone, and enzyme monitoring at initiation, monthly for the first 6 months, and every 3 months thereafter is recommended. Pirfenidone interacts with multiple hepatic enzyme systems; so, monitoring for drug–drug interactions, particularly as patients with IPF are often elderly with multiple comorbid conditions requiring medications, is of utmost importance. The impact of these side effects on HRQL in patients with IPF is unknown.

Interventions to improve health-related quality of life in IPF

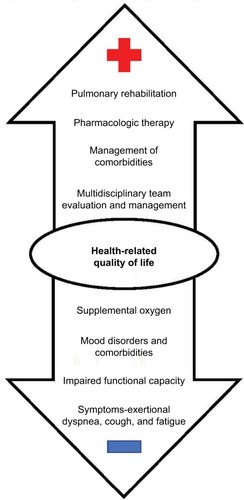

With the approval and increasing use of novel antifibrotic agents that slow disease progression and may allow patients to live longer, determining how to help IPF patients live better is of utmost importance given their overall poor HRQL. Symptoms, including cough, fatigue, and dyspnea in particular, are the most influential drivers of impaired HRQL in IPF ().Citation31 The resultant physical functional limitations due to deconditioning, as patients move less, and eventual social isolation also contribute to impaired quality of life.Citation32 Furthermore, the constraints of supplemental oxygen – tubing, heavy and difficult to move tanks, oxygen needs that cannot be met by a portable concentrator – exacerbate these challenges.Citation33

Figure 1 Positive and negative influences on HRQL in IPF.

Abbreviations: HRQL, health-related quality of life; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Currently, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is the only intervention shown to improve HRQL for patients with IPF. By definition,Citation34 PR is a multidisciplinary program for patients with chronic respiratory disease that, when integrated into a broader treatment strategy, improves functional status, reduces symptoms, increases participation in social and physical activities, and decreases health care costs. These goals are accomplished by combining exercise training, education, counseling, and behavior modification techniques. The delivery of PR is not standardized and can be inpatient, outpatient, or home based, with each program having certain benefits.Citation34

In two randomized controlled clinical trials of outpatient-based PR for IPF patients, there was an improvement in overall HRQL scores during the intervention period.Citation35,Citation36 Similar improvements in HRQL have been reported by several observations trialsCitation37–Citation39 and in a subgroup analysis of PR in ILD.Citation40 Unfortunately, these improvements in HRQL are not sustained following completion of PR programs.

The only pharmacologic therapy shown to impact HRQL in IPF is sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor that may preferentially improve blood flow to better ventilated areas of the lung. In one study of patients with advanced IPF, those treated with sildenafil maintained their baseline level of dyspnea and HRQL as measured by the UCSD-SOBQ and SGRQ, respectively. Comparatively, patients in the placebo group had statistically significant declines in dyspnea and HRQL during the study period.Citation41 Despite these possible benefits, current guidelines recommend against the use of sildenafil due to a lack of benefit on mortality and acute exacerbations in the face of potential adverse events and cost related to therapy.Citation42

Management strategies for patients with IPF

Despite the paucity of interventions that improve HRQL for patients with IPF, comprehensive specialty care is important for accurate diagnosis and appropriate therapeutic management. Making the initial diagnosis of IPF is often challenging. Patients are usually elderly and present with progressive dyspnea. This symptom is often attributed to a comorbid condition such as coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure, delaying targeted evaluation for pulmonary causes. Even after confirming the presence of an ILD with pulmonary function tests or HRCT, multidisciplinary discussion (MDD) with the treating pulmonologist, radiologist, and pathologist is recommended to improve accuracy of the diagnosis.Citation2 For cases that are recommended for biopsy after initial discussion, MDD should be repeated to incorporate pathology results and refine the diagnosis. Patients with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of ILD should be referred to a center with expertise in the management of these conditions. Delayed evaluation at a specialty center is associated with higher risk of death in IPF, specifically, regardless of disease severity.Citation43

After the diagnosis of IPF has been confirmed, practitioners and patients should discuss treatment options and participate in shared decision-making regarding the use of antifibrotic medications. Patients with mild-to-moderate disease (based on FVC), who do not have liver disease, should consider treatment with antifibrotics. The decision of which antifibrotic to choose, if both are available, is primarily driven by three factors: contraindications if present, side-effect profile, and dosing (). Regardless of the choice of antifibrotic, patients must be counseled that these medications may slow the progression of the disease but are not likely to improve their symptoms of breathlessness or improve their HRQL.

Table 1 Comparison of antifibrotic agents approved for the treatment of IPF

Nintedanib should not be used in patients with moderate-to-severe hepatic impairment. Current use of anticoagulation is a relative contraindication to nintedanib, and patients should be cautioned that their risk of bleeding may be increased with concurrent use. There was also a small but increased risk of cardiovascular events reported in patients taking nintedanib compared with placebo. There are no absolute contraindications to treatment with pirfenidone. Pirfenidone is metabolized primarily by the CYP1A2 substrate. Monitoring for drug–drug interactions is very important, and the dose should be reduced if patients are taking CYP1A2 inhibitors (eg, ciprofloxacin).

Both medications, despite known possible side effects, are generally well tolerated. Many side effects, if they do occur, can be managed with supportive care or dose reduction strategies and rarely require drug discontinuation. Both drugs require monitoring for liver enzyme abnormalities after initiation. Patients should be informed of possible side effects, but also counseled that these side effects can be managed and often diminish with time.

With respect to dosing, pirfenidone is titrated up to a final dose of three capsules three times per day when compared with nintedanib, which is one capsule twice per day. Patients’ ability to adhere to the dosing schedule and number of tablets may be a consideration in drug choice.

Irrespective of the decision to initiate therapy with anti-fibrotic medications, optimal management of IPF requires a comprehensive approach, including attention to management of symptoms and treatment of comorbid medical conditions, which are highly prevalentCitation44 in this population.

The most common symptoms that affect patients with IPF are exertional dyspnea, cough, and fatigue. Each of these symptoms is associated with impaired HRQL.Citation29,Citation31,Citation45,Citation46 Unfortunately, symptom management in IPF is challenging with a paucity of effective, durable interventions currently available. PR has a positive impact on lessening symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue,Citation37,Citation47 but the benefits typically are not sustainable following the completion of the program. Supplemental oxygen may improve dyspnea for some patients with IPF, but it is unknown who will benefit and who will not.Citation48,Citation49 The burdens of supplemental oxygen may worsen these symptoms for some patientsCitation33,Citation50,Citation51 and is independently associated with impaired HRQL.Citation5,Citation12,Citation52

In addition to the small observational study demonstrating a positive impact on cough severity in patients treated with pirfenidone, thalidomide has also been shown to lessen symptoms of cough in IPF.Citation53 Further, a novel formulation of inhaled sodium cromoglicate (PA101) showed promising findings on reducing chronic cough in patients with IPF in a Phase II trial.Citation54 Additional research is needed to develop effective, durable therapies to better manage the symptoms patients with IPF often experience.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), emphysema, pulmonary hypertension (PH), and mood disorders are particularly prevalent comorbidities and may impact HRQL. OSA is also highly prevalent in this population,Citation5,Citation12,Citation52,Citation55 and may worsen other comorbidities (eg, PH), if untreated. Poor sleep as a result of OSA may also worsen symptoms of depression and anxiety. Overall, effective treatment of OSA in patients with IPF has been shown to improve fatigue, symptoms of depression, and overall HRQL.Citation56

Emphysema and PH may exacerbate symptoms of IPF, particularly dyspnea and impaired functional capacity. Furthermore, emphysema or PH in combination with IPF may make resting or exertional hypoxemia more likely and more severe, often requiring supplemental oxygen therapy. This combination is particularly deleterious on HRQL given the additive impact of supplemental oxygen therapy.Citation50

Mood disorders are also common in patients with IPF, with as many as 49% of patients having depression and 31% having anxiety.Citation57 The dyspnea that IPF patients experience is strongly associated with and drives symptoms of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, mood symptoms may heighten the perception of dyspnea, leading to a reinforcing negative cycle and worsening HRQL. Pharmacologic treatment of depression and anxiety has not been studied in IPF, necessitating an individualized approach for each patient. PR and disease-specific support groups may provide patients with a sense of validation and shared experience and may improve symptoms.Citation47 These modalities, in addition to cognitive-behavioral therapy and palliative care, may be useful adjuncts for the treatment of mood disorders.

Screening IPF patients for these prevalent comorbid conditions is crucial to optimizing medical management, decreasing symptom burden, and potentially improving outcomes, including HRQL.

In addition to decisions regarding antifibrotic medications and treatment of symptoms and comorbidities, IPF patients should be monitored for disease progression with regular pulmonary function tests. All patients with IPF should be evaluated for the need for supplemental oxygen therapy with an oxygen titration study. If supplemental oxygen is necessary, patients and caregivers should be educated about realistic expectations for oxygen use including a variable impact on symptoms and the likely overall negative impact on quality of life for both.Citation48,Citation51,Citation58,Citation59 Patients should also be referred to PR programs for exercise training to improve functional capacity,Citation37,Citation40,Citation60 to gain information about their disease, and to improve HRQL as previously discussed. Appropriate patients should be referred for lung transplant evaluation at a dedicated center. Furthermore, depending on the stage and pace of disease, patient functional status and goals, palliative care involvement may be appropriate for symptom management and end-of-life planning.

Conclusion

Despite recent advances in the treatment of IPF with antifibrotic agents that slow the decline in lung function, it remains an insidiously progressive and incurable disease. Patients suffer with significantly impaired quality of life due to the impact of disease on their physical, functional, emotional, and psychosocial well-being. Though antifibrotics have been shown to slow the rate of disease progression, they have not been shown to improve patients’ quality of life. Until there are curative treatment options available, future research should focus on the impact of symptom-targeted therapies, combination therapy with existing antifibrotics, and multidisciplinary treatments including PR and palliative care on HRQL.

A patient-centered, comprehensive approach to care including attention to symptoms, comorbidities, and advanced care planning remains the cornerstone of care of patients with IPF. As both disease- and symptom-specific therapeutics continue to advance, it is increasingly important to assess not only the impact on disease progression and mortality, but the impact on patients’ lives on a day-to-day basis. With the ultimate goal of improving both quality and quantity of life for patients with IPF, it is imperative to understand the impact of emerging interventions on patient-centered outcomes.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

BAG thanks the generous contribution of the Reuben M Cherniak Fellowship Award from the National Jewish Health for providing ongoing support for her research.

Disclosure

JSL is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K23-HL138131. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AhluwaliaNSheaBSTagerAMNew therapeutic targets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Aiming to rein in runaway wound-healing responsesAm J Respir Crit Care Med2014190886787825090037

- RaghuGCollardHREganJJAn official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and managementAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183678882421471066

- OlsonALSwigrisJJLezotteDCNorrisJMWilsonCGBrownKKMortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003Am J Respir Crit Care Med2007176327728417478620

- YountSEBeaumontJLChenSYHealth-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisLung2016194222723426861885

- TomiokaHImanakaKHashimotoKIwasakiHHealth-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis--cross-sectional and longitudinal studyIntern Med200746181533154217878639

- van ManenMJGeelhoedJJTakNCWijsenbeekMSOptimizing quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisTher Adv Respir Dis201711315716928134007

- OlsonALBrownKKSwigrisJJUnderstanding and optimizing health-related quality of life and physical functional capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisPatient Relat Outcome Meas20167293527274328

- SwigrisJJEsserDWilsonHPsychometric properties of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir J2017491160178828100551

- SwigrisJJBrownKKBehrJThe SF-36 and SGRQ: validity and first look at minimum important differences in IPFRespir Med2010104229630419815403

- SwigrisJJEsserDConoscentiCSBrownKKThe psychometric properties of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a literature reviewHealth Qual Life Outcomes20141212425138056

- KreuterMSwigrisJPittrowDHealth related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: insights-IPF registryRespir Res201718113928709421

- SwigrisJJWilsonSRGreenKESprungerDBBrownKKWamboldtFSDevelopment of the ATAQ-IPF: a tool to assess quality of life in IPFHealth Qual Life Outcomes201087720673370

- YorkeJSpencerLGDuckACross-Atlantic modification and validation of the A Tool to Assess Quality of Life in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (ATAQ-IPF-cA)BMJ Open Respir Res201411e000024

- GraneyBJohnsonNEvansCJLiving with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (L-IPF): developing a patient-reported symptom and impact questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life in IPFAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195A5353

- PatelASSiegertRJKeirGJThe minimal important difference of the King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease Questionnaire (K-BILD) and forced vital capacity in interstitial lung diseaseRespir Med201310791438144323867809

- PatelASSiegertRJBrignallKThe development and validation of the King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease (K-BILD) health status questionnaireThorax201267980481022555278

- RicheldiLdu BoisRMRaghuGEfficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2014370222071208224836310

- KingTEBradfordWZCastro-BernardiniSA phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2014370222083209224836312

- TaniguchiHEbinaMKondohYPirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir J201035482182919996196

- NoblePWAlberaCBradfordWZPirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trialsLancet201137797791760176921571362

- GeorgeGVaidUSummerRTherapeutic advances in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisClin Pharmacol Ther2016991303226502087

- RicheldiLCostabelUSelmanMEfficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2011365121079108721992121

- RicheldiLCottinVdu BoisRMNintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: combined evidence from the TOMORROW and INPULSIS(®) trialsRespir Med2016113747926915984

- KimESKeatingGMPirfenidone: a review of its use in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisDrugs201575221923025604027

- NoblePWAlberaCBradfordWZPirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trialsEur Respir J201647124325326647432

- LeyBSwigrisJDayBMPirfenidone reduces respiratory-related hospitalizations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017196675676128471697

- NathanSDAlberaCBradfordWZEffect of continued treatment with pirfenidone following clinically meaningful declines in forced vital capacity: analysis of data from three phase 3 trials in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisThorax201671542943526968970

- EakinEGResnikoffPMPrewittLMRiesALKaplanRMValidation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. University of California, San DiegoChest199811336196249515834

- SwigrisJJGouldMKWilsonSRHealth-related quality of life among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisChest2005127128429415653996

- van ManenMJGBirringSSVancheriCEffect of pirfenidone on cough in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir J2017504170115729051272

- NishiyamaOTaniguchiHKondohYHealth-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. What is the main contributing factor?Respir Med200599440841415763446

- BelkinASwigrisJJHealth-related quality of life in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: where are we now?Curr Opin Pulm Med201319547447923851327

- GraneyBAWamboldtFSBairdSLooking ahead and behind at supplemental oxygen: a qualitative study of patients with pulmonary fibrosisHeart Lung201746538739328774655

- NiciLDonnerCWoutersEAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173121390141316760357

- NishiyamaOKondohYKimuraTEffects of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisRespirology200813339439918399862

- HollandAEHillCJConronMMunroPMcdonaldCFShort term improvement in exercise capacity and symptoms following exercise training in interstitial lung diseaseThorax200863654955418245143

- SwigrisJJFaircloughDLMorrisonMBenefits of pulmonary rehabilitation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisRespir Care201156678378921333082

- OzalevliSKaraaliHKIlginDUcanESEffect of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisMultidiscip Respir Med201051313722958625

- KozuRSenjyuHJenkinsSCMukaeHSakamotoNKohnoSDifferences in response to pulmonary rehabilitation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration201181319620520516666

- DowmanLHillCJHollandAEPulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201410CD006322

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research NetworkZismanDASchwarzMA controlled trial of sildenafil in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2010363762062820484178

- RaghuGRochwergBZhangYAn Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice GuidelineAm J Respir Crit Care Med20151922e3e1926177183

- LamasDJKawutSMBagiellaEPhilipNArcasoySMLedererDJDelayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184784284721719755

- RaghuGAmattoVCBehrJStowasserSComorbidities in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: a systematic literature reviewEur Respir J20154641113113026424523

- SwigrisJJStewartALGouldMKWilsonSRPatients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their livesHealth Qual Life Outcomes200536116212668

- van ManenMJBirringSSVancheriCCough in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir Rev20162514127828627581827

- RyersonCJCayouCToppFPulmonary rehabilitation improves long-term outcomes in interstitial lung disease: a prospective cohort studyRespir Med2014108120321024332409

- CaoMWamboldtFSBrownKKSupplemental oxygen users with pulmonary fibrosis perceive greater dyspnea than oxygen non-usersMultidiscip Respir Med2015103726693009

- NishiyamaOTaniguchiHKondohYA simple assessment of dyspnoea as a prognostic indicator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir J20103651067107220413545

- BelkinAAlbrightKSwigrisJJA qualitative study of informal caregivers’ perspectives on the effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisBMJ Open Respir Res201411e000007

- GraneyBAWamboldtFSBairdSInformal caregivers experience of supplemental oxygen in pulmonary fibrosisHealth Qual Life Outcomes201715113328668090

- CullenDLStifflerDLong-term oxygen therapy: review from the patients’ perspectiveChron Respir Dis20096314114719643828

- HortonMRSantopietroVMathewLThalidomide for the treatment of cough in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2012157639840622986377

- BirringSSWijsenbeekMSAgrawalSA novel formulation of inhaled sodium cromoglicate (PA101) in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, proof-of-concept, phase 2 trialLancet Respir Med201751080681528923239

- LancasterLHMasonWRParnellJAObstructive sleep apnea is common in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisChest2009136377277819567497

- MermigkisCBouloukakiIAntoniouKObstructive sleep apnea should be treated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisSleep Breath201519138539125028171

- KingCSNathanSDIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: effects and optimal management of comorbiditiesLancet Respir Med201751728427599614

- BellECCoxNSGohNOxygen therapy for interstitial lung disease: a systematic reviewEur Respir Rev20172614316008028223395

- ViscaDMontgomeryAde LauretisAAmbulatory oxygen in interstitial lung diseaseEur Respir J201138498799021965506

- NajiNAConnorMCDonnellySCMcdonnellTJEffectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in restrictive lung diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil200626423724316926688