Background

The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published their first European-specific guidelines in 2003. The decision to publish their own recommendations recognized that their historical endorsement of the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Society of Hypertension (ISH) guidelines, with some adaptation to the European situation, fell short of addressing the significant differences in economic resources available, and diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations between Europe and the rest of the world. The 2003 ESH/ESC Guidelines have since been revised and updated in light of changes in the field and in the pursuit of good medicine and practice, and have recently been published in their second incarnation in the Journal of Hypertension (CitationESH/ESC Hypertension Practice Guidelines Committee 2003, Citation2007).

Despite the unequivocal cardiovascular (CV) risk conferred by high blood pressure (BP), a significant number of people with hypertension are unaware of their condition and target BP levels are seldom achieved (CitationBurt et al 1995; CitationAmar et al 2003; CitationMancia et al 2005). The 2007 ESH/ESC Guidelines emphasize the need to extend procedures for the effective capture, diagnosis and treatment of hypertension to a larger fraction of the clinical profession to benefit a greater number of patients. The scope of the Guidelines covers: definition and classification, diagnostic evaluation, therapeutic management and approach, treatment strategies, special conditions, associated risk factors, screening for secondary forms of hypertension, follow-up and implementation.

The aim of this supplement is to distil and summarize the key recommendations, with a particular emphasis on implications for practice from a primary care perspective. The recommendations are based on data from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies as appropriate, and aim to facilitate decision-making and practice for all healthcare providers involved in the management of hypertension.

Definition

The WHO cites high BP as the leading cause of death worldwide (Erzzati et al 2002) because of its prevalence and its status as a significant CV risk factor (CitationWolf-Maier et al 2003; CitationKearney et al 2005; CitationMartiniuk et al 2007). The continuous relationship between both systolic and diastolic BP and CV morbidity and mortality (including that relating to both coronary events and stroke) has been demonstrated in a number of observational studies and is continuous to systolic and diastolic levels of 115–110 mmHg and 75–70 mmHg, respectively (CitationJoint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure 1977, Citation1980; CitationCollins et al 1990; MacHahom et al 1990; CitationProspective Studies Collaboration 2002). Furthermore, both systolic and diastolic BP are independently related to heart failure, peripheral artery disease (PAD) and end-stage renal disease (CitationCriqui et al 1992; CitationKannel et al 1996; CitationKlag et al 1996; CitationLevy et al 1996).

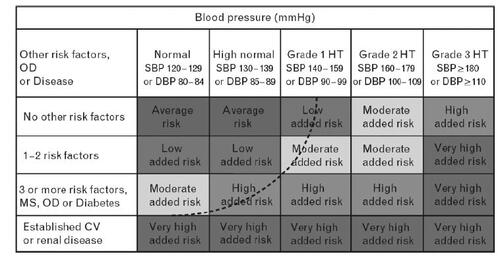

For practical reasons, including their intrinsic use in key RCTs, classification of hypertension and risk assessment should be based on systolic and diastolic BP. However, the Guidelines also recognize that pulse pressure may be a useful parameter to identify systolic hypertension in elderly patients who may be at particularly high risk (CitationBlacher et al 2000; CitationGasowski et al 2002; CitationLaurent 2006). The Guidelines define optimal BP as <120 (systolic) and <80 (diastolic), and normal BP as 120–129 (systolic) and/or 80–84 (diastolic). illustrates the classification of hypertension, as retained from the 2003 ESH/ESC Guidelines, with recognition that the threshold for hypertension should be regarded as flexible; being higher or lower based on the total CV risk of each individual. It is of note, however, that if a patient’s systolic and diastolic pressures lie in different categories, the risk relating to the higher category should be attributed to the patient. Furthermore, low diastolic BP (eg, 60–70 mmHg) should be regarded as an additional risk. Isolated systolic hypertension does not appear in but is defined in the Guidelines as ≥140 (systolic) and <90 (diastolic).

Figure 1 Stratification of CV risk into four categories.

Low, moderate, high and very high risk refer to 10-year risk of a CV fatal or non-fatal event. The term “added” indicates that in all categories risk is greater than average. The dashed line indicates how definition of hypertension may be variable, depending on the level of total CV risk.

Total cardiovascular risk

The 2007 Guidelines emphasize that diagnosis and management of hypertension should be related to quantification of total (or global) CV risk, usually expressed as the absolute risk of having a CV event within 10 years. This more holistic approach recognizes that the majority of patients with high BP exhibit additional CV risk factors, and the potentiation of concomitant BP and metabolic risk factors leads to a CV risk that is more than the sum of the individual components (CitationMultiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group 1986; CitationAssmann and Schulte 1988; CitationWei et al 1996; CitationKannel et al 2000; CitationThomas et al 2001; CitationAsia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration 2005; CitationMancia et al 2006a). The total CV risk should be used to grade intensity of therapeutic approach and guide decisions on treatment strategies, including:

Initiation of drug treatment

BP threshold and target

Use of combination treatment or additional non-antihypertensive agents

Cost-effectiveness.

The Guidelines summarize factors influencing prognosis and risk classification (see and ), yet it is acknowledged that there are limitations to the application of standardized CV risk models in a real-world setting, and also intrinsic conceptual limitations associated with the rationale of estimating total risk as a way to best assign limited resources.

Box 1 High/very high-risk subjects

Table 1 Factors influencing prognosis

Diagnosis

The aim of diagnostic procedures is to establish BP levels, identify secondary causes of hypertension and evaluate the overall CV risk through assessment of risk factors, target organ damage and concomitant disease or accompanying clinical conditions.

Measurement

BP measurements are most accurate when an average is taken of multiple reads recorded over at least 2–3 visits. However, in severe cases, diagnosis can be based on one measurement alone. Practical considerations when measuring BP in the clinical setting are summarized in .

Box 2 Guidance for correct office blood pressure measurements

Recent studies form a growing body of evidence to suggest that out-of-office BP readings are more closely correlated to severity of hypertension than those taken in the clinical setting and, as such, are a more accurate predictor of true CV risk (CitationKhattar et al 1998; CitationFagard et al 2000; CitationBobrie 2004, CitationFagard and Celis 2004; CitationFagard et al 2005a; CitationOhkubo et al 2005; CitationVerdecchia et al 2005; CitationHansen et al 2006; CitationMancia et al 2006b). The Guidelines’ recommendations regarding self-measurement of BP at home include:

Use of validated and semiautomatic devices for simplicity and accuracy

Taking measurements while in the sitting position (after several minutes of rest) and keeping the arm at heart level during measurement with wrist devices

Measurement of BP in the morning and in the evening, and both pre- and post-treatment to monitor the effect of drug intake.

The Guidelines also advise that it is prudent to educate patients about spontaneous changes in BP that may result in fluctuating readings. Clinicians are also reminded of the phenomenon of isolated office (or clinic) hypertension, ie, 130–135/85 mmHg as measured at home approximately corresponds to 140/90 mmHg.

Physical examination and laboratory investigations

In addition to BP measurements, heart rate, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference should be carefully recorded. Physical examination should also search for evidence of additional risk factors, signs of secondary hypertension or evidence of organ damage, eg, palpation of enlarged kidneys, ausculation of abdominal murmurs or of precordial or chest murmurs, features of Cushing Syndrome, or diminished and delayed femoral pulses and reduced femoral BP.

Laboratory examinations can provide evidence of additional risk factors. Routine laboratory investigations should include blood chemistry for fasting glucose; total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol; triglycerides (fasting); urate; creatinine; potassium, hemaglobin and hematocrit, urinalysis by a dipstick test and electrocardiogram. Further tests are recommended and include home and ambulatory BP monitoring, ankle-brachial index (ABI), echocardiogram, fundoscopy, glucose tolerance test, pulse wave velocity measurement, quantitative proteinuria and carotid ultrasound. The younger the patient, the higher the BP and the faster the development of their hypertension, the more thorough the diagnostic assessment should be.

Family and clinical history

There is often a family history of high BP in hypertensive patients, suggesting that inheritance contributes to the pathogenesis of the disorder. A comprehensive family history should be taken, with particular attention being paid to hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, premature coronary heart disease, stroke, PAD and renal disease. The clinical history should include:

Past history and duration of previous levels of high BP and subsequent antihypertensive treatment

Symptoms suggestive of secondary causes of hypertension

Lifestyle factors (eg, physical activity level, diet, smoking and alcohol consumption) and past or current symptoms of coronary disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular disease (PVD), renal disease, diabetes mellitus, gout, dyslipidemia, asthma or other significant illnesses and related medication prescribed.

Subclinical organ damage

There is a large body of evidence available on the crucial role of subclinical organ damage in determining the CV risk of individuals with and without high BP. In recognition of the importance of subclinical organ damage as an intermediate stage in the continuum of vascular disease and as an indicator of total CV risk, the Guidelines devote a section to the discussion of the evidence for the risk represented by various organ abnormalities and methods for their detection (see ). It is important to note that arterial assessments, as evaluated by arterial stiffness, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, ankle-brachial BP index and carotid wall thickness, now figure prominently in the list of sub-clinical organ damage.

Table 2 Methods of subclinical organ damage detection

Treatment strategies

Non-pharmacological interventions

Positive lifestyle changes should be instituted in both patients with hypertension and in those with normal-high BP and additional risk factors. Lifestyle interventions should be implemented, irrespective of whether pharmacological therapy is prescribed, to lower BP and to help control other risk factors and clinical conditions. In so doing, the subsequent antihypertensive pill burden for patients may be reduced and the associated economic consequences minimized.

Effectiveness of lifestyle measures can vary and long-term compliance is low (CitationHaynes et al 2002). In order to optimize outcomes, interventions should be introduced alongside adequate behavioral and expert support, and reinforced periodically. In light of poor adherence in the long term, patients under non-pharmacological treatment should receive close follow-up to ensure that drug therapy is initiated when required. Appropriate lifestyle interventions include: smoking cessation, moderation of alcohol consumption, increased physical activity, sodium restriction and advice on weight management and healthy eating (CitationDickinson et al 2006).

Smoking cessation

Smoking is a powerful CV risk factor (CitationDoll et al 1994) and cessation may be the single most effective lifestyle measure for the prevention of a large number of CV diseases, including stroke and myocardial infarction (MI) (CitationRosenberg et al 1985; CitationManson et al 1992; CitationDoll et al 1994). Nicotine replacement therapy (CitationSilagy et al 1994), bupropion therapy (CitationTonstad et al 2003) or varenicline (CitationNides et al 2006) should be considered to facilitate smoking cessation.

Moderation of alcohol consumption

The relationship between alcohol consumption, BP levels and the prevalence of hypertension is linear (Puddey et al 1994), and high consumption is related to a high risk of stroke (CitationWannamethee and Shaper 1996). Trials investigating alcohol reduction have shown a significant drop in systolic and diastolic BPs (Dickson et al 2006). The Guidelines recommend a daily intake of ≤20–30 g ethanol/day for male patients with hypertension and 10–20 g ethanol/day for female patients. All patients with hypertension are also recommended to avoid binge drinking.

Physical activity

Lack of physical fitness is strongly correlated with CV mortality, independent of BP and other risk factors (Sandvick et al 1993). Even moderate levels of exercise can lower BP (CitationFagard 2001), reduce body weight, fat, waist circumference, increase insulin sensitivity and HDL-cholesterol levels. Sedentary patients are recommended to undertake 30–45 minutes of moderate intensity, primarily endurance, activity daily (eg, walking, jogging, swimming). This can then be supplemented with resistance exercise (CitationJennings 1997; CitationStringer et al 2005). In patients in whom hypertension is poorly controlled, however, the Guidelines warn that heavy physical exercise and maximal exercise testing should be discouraged or postponed until appropriate drug treatment has been instituted and BP lowered (CitationFagard et al 2005b).

Sodium restriction

Epidemiological studies suggest that dietary salt intake is a contributor to BP elevation and to the prevalence of hypertension (CitationLaw 1997; CitationWHO/FAO 2003). The benefit of sodium restriction is greater in blacks, middle-aged and older patients, as well as in individuals with hypertension, diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Ideal daily intake of sodium chloride is targeted at 3.8 g, although it is recognized that a target of <5 g may be more realistic and achievable.

Weight management and healthy eating

Weight loss should be encouraged in overweight patients; support and counselling from trained dieticians may be beneficial. Healthy eating should be promoted because of its BP-lowering effects (CitationSacks et al 2001): increased fruit and vegetable intake (4–5 servings, or 300 g/day) and a reduction in saturated and total fat intake.

Pharmacological interventions

The primary goal of treatment in patients with hypertension is to achieve maximum reduction in the long-term total risk of CVD. This requires the treatment of both raised BP and all associated reversible risk factors. BP targets are (systolic/diastolic):

≤140/90 mmHg in all patients with hypertension

≤130/80 mmHg in patients with diabetes and in high-risk, or very high-risk, patients (eg, those with associated clinical conditions such as stroke, MI, renal dysfunction, proteinuria).

It may be difficult to achieve BP targets, especially in elderly and diabetic patients, and in patients with CV damage. It is recommended that antihypertensive treatment be initiated before significant CV damage develops to maximize the probability of achieving target BP.

Treatment options

There are five major classes of such agents licensed for initiation or maintenance of hypertension, alone or in combination: thiazide diuretics; calcium antagonists (CA); ACE inhibitors (ACEI); agiotensin receptor antagonists (ARB), and β-blockers (BB). The choice of a specific drug or combination should take into account the following:

○ Previous patient exposure to, and history with, a class of compounds

○ CV risk associated with agent and the patient’s CV risk profile

○ Presence of other disorders and conditions (see )

Table 3 Guideline’s recommendations on preferred drug classes for various conditions and those conditions for which there is compelling evidence, or evidence suggestive, of contraindication to use of a class of agents

○ Possible drug interactions

○ Cost considerations (although these should not predominate over efficacy, tolerability and patient protection)

○ Side-effects and their potential impact on compliance

○ Duration of antihypertensive effect – once-daily administration should be preferred because of correlations between simplicity of treatment regimen and improved compliance.

Monotherapy

Where possible, treatments should be initiated as low-dose monotherapy. Where the initiating dose of the original agent proves ineffective, it can be increased to its maximum or an alternate agent from a different class can be prescribed. This sequential monotherapy approach is recommended in uncomplicated hypertensives and in the elderly, and can help establish to which agent the patient responds best. However, it can be laborious and can lead to low compliance and delayed control of BP in patients with high-risk hypertension.

Combination therapy

Although it is possible to achieve target BP (<140/90 mmHg) in some patients through lifestyle interventions and monotherapy, the majority of patients (70%–80%) require the use of more than one agent (CitationDickerson et al 1999; CitationMorgan et al 2001). Antihypertensive agents can be combined if they have different and complementary mechanisms of action and where their combined use either offers greater efficacy than that of either of the combination components, or a favorable tolerability profile, or both.

The Guidelines recommend consideration of combination treatment as first choice, particularly when there is a high CV risk, to avoid delay in treatment of high BP in high-risk individuals. Use of combination therapy at treatment initiation also offers the benefit of prescribing both agents at their lowest dose. This should result in a minimization of potential side-effects and improve related compliance, especially as fixed-dose combinations offer dual administration via one tablet, retaining the simplicity of the treatment regimen. The following two-drug combinations have been found to be effective and well tolerated, and have been favorably used in randomized efficacy trials:

○ Thiazide diuretic and ACEI

○ Thiazide diuretic and ARB

○ Thiazide diuretic and BB (although this should be avoided in patients with metabolic syndrome or high risk of incident diabetes because of dysmetabolic effects)

○ CA and ACEI

○ CA and ARB

○ CA and thiazide diuretic

○ BB and CA (dihydropiridine)

When it is not possible to achieve BP control through lifestyle interventions and the use of two drugs, a combination of three agents should be tried. If systolic and diastolic BP goals fail despite treatment, including a therapeutic plan, lifestyle measures and the prescription of a diuretic and at least two other drugs, the patient may have resistant hypertension. lists some of the main causes of resistant hypertension. The first management step is a careful elicitation of the history, followed by a thorough examination to exclude secondary causes of hypertension. It is also crucial to assess whether compliance is adequate. Ultimately, many patients will need administration of more than three drugs, but the optimal choice of third, fourth and fifth-line antihypertensive agents has not been properly addressed by RCTs.

Table 4 Common causes of resistant hypertension

Therapeutic approach

All patients whose repeated BP measurements show grade 2 or 3 hypertension are definite candidates for antihypertensive treatment. The body of evidence for the benefit of treating grade 1 hypertension is less robust as specific trials have not addressed the issue. The Guidelines support consideration of antihypertensive interventions when systolic BP is ≥140 mmHg.

Specific patient groups

It is acknowledged that Guidelines deal with a disease, while physicians deal with patients. Every patient has specific needs and particularities for which treatment is individualized to achieve maximum therapeutic effect. With a view to offering guidance on appropriate targets and treatment in less standard situations, the Guidelines discuss therapeutic approaches in special conditions.

Elderly patients

RCTs have shown that older patients (≥60 years) benefit from antihypertensive drug treatment in terms of reduced CV morbidity and mortality (CitationCollins and MacMahon 1994; CitationStaessen et al 2000). As a result, a treatment goal of BP < 140/90 mmHg is recommended in elderly patients with hypertension. However, it is conceded that achievement of this target may be difficult in the elderly and is likely to require combination therapy.

The Guidelines advise that treatment should proceed in line with general guidelines and with full consideration of risk factors, but that the initial dose used, and subsequent titration, should be more gradual to minimize adverse events. It is also of note that, as there is an increased risk of postural hypotension in elderly patients, BP measurements should be undertaken with patients in the erect posture. If well tolerated, continuation of antihypertensive regimen post 80 years is recommended, but initiation in patients ≥80 remains unproven.

Diabetes

The coexistence of hypertension and either type 1 or type 2 diabetes substantially increases risk of developing renal and other organ damage, leading to increased incidence of stroke, CHD, congestive heart failure, PAD and CV mortality (CitationStamler et al 1993). For this reason a strict treatment BP target of <130/80 mmHg is recommended in patients with either form of diabetes.

Lifestyle interventions (especially caloric intake and increased physical activity) are also strongly encouraged, as is the initiation of pharmacological approaches when BP is in the high-normal range. The Guidelines suggest that a treatment regimen including an ARB or ACEI may afford antiproteinuric effects and additional protection on appearance and progression of renal damage. Where monotherapy is appropriate, an ARB or ACEI is recommended and should be included in combination regimens, which are frequently required. As in the case of elderly patients, an increased risk of postural hypotension in patients with diabetes leads to the advice that BP should be measured while patients are in the erect posture.

Cerebrovascular disease

Antihypertensive treatment markedly reduces the incidence of recurrent stroke and lowers the associated risk of cardiac events in patients with a history of stroke or TIA (CitationPROGRESS Collaborative Study Group 2001; CitationPATS Collaborative Group 1995). For patients with cerebrovascular disease, a treatment goal of BP <130/80 mmHg is recommended and pharmacological interventions should be initiated when BP is in the high-normal range.

Evidence suggests the benefit of antihypertension in this patient group is afforded by BP reduction (CitationPROGRESS Collaborative Study Group 2001; CitationArima et al 2006). The Guidelines therefore advise the use of all available drugs and rational combinations in order to reach target BP. Observational studies also indicate a correlation between BP value and cognitive decline and incidence of dementia, which may be delayed by antihypertensive treatment (CitationLauner et al 1995; CitationSkoog et al 1996; CitationKilander et al 1998). Data are currently lacking in acute stroke, but initiation of treatment is advised when post-stroke clinical conditions are stable.

Coronary heart disease and heart failure

Patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) often have a history of hypertension and the risk of a fatal or non-fatal coronary event post MI is greater if BP is elevated (CitationDomanski et al 1999; CitationYap et al 2007). The Guidelines recommend post-MI administration of BB, ACEI or ARBs, which have been shown to reduce the incidence of recurrent MI and death largely because of direct organ protective properties of the agents, but may be supported by the associated reduction in BP as a result of these agents (CitationFreemantle et al 1999; CitationDickstein et al 2002; CitationPfeffer et al 2003; CitationShekelle et al 2003; CitationLee et al 2004). The benefit of BP control is also true for patients with chronic CHD. Raised BP is relatively rare in patients with congestive heart failure; treatment in these patients can include thiazide and loop diuretics, BBs, ACEIs and ARBs, but the Guidelines warn against the use of a CA in these patients, unless needed to control BP or anginal symptoms.

Atrial fibrillation

Hypertension is the most important risk factor for atrial fibrillation (AF) on a population basis (CitationKannel et al 1998). The Guidelines recommend the benefit of blockade of the renin-angiotensin system by either an ACEI or ARB in patients with paroxysmal AF and congestive heart failure. In permanent AF, BB and non-dihydropiridine CA remain important classes of drugs for the control of ventricular rate.

Women

Both genders respond to antihypertensive agents and benefit from the effects of lowering BP, but there are additional considerations that should be taken into account when prescribing for women. If women are pregnant, or planning a pregnancy, the Guidelines advise avoidance of potentially teratogenic drugs (ie, ACEIs and ARBs). Other female-specific points of note made in the Guidelines are: that oral contraception causes mild BP elevation – the progestogen-only pill is an option in women shown to have high BP; that hormone replacement therapy is not currently recommended for cardio protection in postmenopausal women because of its associated adverse events, and the potential adverse effects of hypertension on neonatal and maternal outcomes. The Guidelines make the following recommendation for pregnant women:

○ Systolic BP 140–149 mmHg or diastolic BP 90–95 mmHg: non-pharmacological management, including supervision and restriction of activities

○ BP ≥140/90 mmHg (with or without proteinuria): drug treatment is indicated

○ Systolic BP ≥170 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥110 mmHg: emergency hospitalization

○ Non-severe hypertension: oral methyldopa, lebetalol, CA or possibly BB

○ Pre-eclampsia with pulmonary edema: nitroglycerine is the drug of choice; diuretic therapy is inappropriate.

Intravenous labetalol, oral methyldopa and oral nifedipine are indicated for emergency treatment. Calcium supplementation, fish oil and low-dose aspirin are not recommended, although low-dose aspirin may be used prophylactically in women with a history of early onset pre-eclampsia.

Metabolic syndrome

The metabolic syndrome is characterized by the variable combination of visceral obesity and alterations in glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism and BP. It is most prevalent in middle-aged and elderly populations and confers significant increased risk of CV morbidity and mortality, developing diabetes, organ damage and new onset hypertension (CitationVasan et al 2001a, Citationb; CitationLakka et al 2002; CitationVasan et al 2002; CitationDunder et al 2003; CitationResnick et al 2003; CitationGirman et al 2004; CitationDekker et al 2005; CitationMule et al 2005; CitationSchmidt et al 2005; CitationMancia et al 2007a).

The Guidelines recommend implementation of lifestyle interventions, including weight loss of 7%–10% over 6–12 months, as the first and main treatment strategy (CitationMancia et al 2007b). In patients with metabolic syndrome, a more in-depth assessment of subclinical organ damage is recommended, as is measurement of ambulatory and home BP.

Where there is hypertension, or possibly high-normal BP, it is advised to initiate treatment with a blocker of the renin-angiotensin system to minimize the facilitation of diabetes onset potentially conferred by other agents. If necessary, a CA or a low-dose thiazide diuretic may be used in combination. Statins should also be prescribed in the presence of dyslipidemia, and antidiabetic drugs for diabetes.

Secondary hypertension

A secondary form of hypertension is suggested by a severe BP elevation, sudden onset or worsening of hypertension and BP responding poorly to drug therapy. Simple screening for secondary forms of hypertension can be obtained from clinical history, physical examination and routine laboratory investigations. The Guidelines outline specific diagnostic procedures for the following conditions:

Renal parenchymal disease

Renovascular hypertension

Pheochromocytoma

Primary aldosteronism

Cushing’s syndrome

Obstructive sleep apnea

Coarctation of the aorta

Drug-induced hypertension

Hypertension emergencies

Severe forms of high BP are associated with acute damage to target organs, resulting in hypertensive emergencies. They tend to be rare, but are life threatening and should be treated promptly in the same way as chronic BP elevations, although caution should be taken in the rapid reduction of BP in patients with acute stroke. The most important hypertension emergencies are listed in .

Table 5 Hypertensive emergencies

Associated risk factors

The Guidelines also offer recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of associated risk factors, covering lipid-lowering agents, antiplatelet therapy and glycemic control.

Lipid lowering agents

Statin therapy should be considered in all patients with hypertension and established CVD or with type 2 diabetes. Total serum targets of ≤4.5 mmol/L (175 mg/dL) and LDL cholesterol levels of ≤2.5 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) are recommended. A statin should also be considered in patients with hypertension without overt CVD but with high CV risk (≥20% risk of events in 10 years), even if their baseline total and LDL serum cholesterol levels are not elevated.

Antiplatelet therapy

Antiplatelet therapy, in particular low-dose aspirin, should be prescribed to patients with hypertension and a history of CV events, provided that there is no excessive risk of bleeding. Low-dose aspirin should also be considered in patients with hypertension who are ≥50 years old, even in those without a history of CVD, if they have a moderate increase in serum creatinine or high CV risk. In all these conditions, the benefit-to-risk ratio (weighed as a reduction of MI risk against bleeding) has been proven favorable. To minimize the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, antiplatelet treatment should be initiated only when effective BP control has been achieved.

Glycemic control

Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance are major risk factors for CVD (CitationStamler et al 1993; CitationKnowler et al 1997; CitationHaffner et al 1998), making effective glycemic control of great importance in patients with hypertension and diabetes. In these patients dietary and drug treatment of diabetes should aim at lowering plasma fasting glucose to values ≤6 mmol/l (108 mg/dl) and at a glycated hemoglobin of <6.5%.

Compliance

Treatment of hypertension should be continued for life as cessation in correctly diagnosed patients is associated with a return to the hypertensive state. However, cautious downward titration of established treatment may be attempted in low-risk patients after long-term BP control, particularly if non-pharmacological treatment can be successfully implemented and if it is associated with home monitoring.

Educating patients of the risk of hypertension and the benefit of treatment can help improve compliance. Clear written and oral instructions on disease and treatment plans should be offered to the patient and their family. Simplifying the treatment regimen (eg, use of a once-daily medication) and tailoring it to the patient’s lifestyle can also improve compliance. Retaining open channels of communication with the patient, regarding side-effects, their potential problems with adherence and offering reliable support and affordable prices can also be beneficial.

Patient follow-up

Patients on non-pharmacological interventions require frequent follow-up visits to maximize compliance, to reinforce the treatment approach and to monitor BP, allowing a prompt and timely switch to pharmacological interventions if necessary.

During the titration phase of pharmacological therapy, patients should receive regular checkups (eg, every 2–4 weeks) in order to optimize the treatment regimen – drug dose and/or combination – to maximize effectiveness and minimize adverse events. The Guidelines advise an added benefit of instructing patients to self-measure BP at home during this phase.

Frequency of visits can be reduced considerably once target BP and other treatment goals have been achieved, eg, every 6 months for patients with low additional CV risks, but more frequently where there are concomitant risk factors. However, the Guidelines underline several benefits of ensuring regularity and frequency of follow-up visits, including the reinforcement of a strong doctor-patient relationship (crucial to treatment effectiveness and compliance) and the opportunity to monitor all reversible risk factors and assess target organ damage (LV mass and carotid artery wall thickness are slow, so a maximum once-yearly examinations are recommended).

Cost-effectiveness

Several studies have shown that in high- and very high-risk patients, treatment of hypertension is largely cost-effective – the reduction in the incidence of CVD and death largely offsets the cost of treatment despite its lifetime duration (CitationAmbrosioni 2001). Early initiation of treatment is crucial and primarily aims to prevent onset and/or progression of organ damage that would result in low-risk patients progressing to the high-risk category over time. Several trials of antihypertensive have suggested that some of the major CV risk changes may be difficult to reverse, and that restricting antihypertensive therapy to patients at high or very high risk may be far from an optimal strategy (CitationHansson et al 1998; CitationZanchetti et al 2001). Another observation made in the Guidelines is that the cost of hypertensive drug treatment is often contrasted with lifestyle measures, which are considered to be cost-free. However, this can be misleading as real implementation, and therefore effectiveness, of lifestyle changes requires behavioral support, counseling and reinforcement.

Implementation

The Guidelines conclude with the recognition that there are numerous barriers between recommendations and their adoption in practice. One important obstacle can be the consideration by physicians that guidelines deal with the disease while the practice of medicine deals with the individual patient. In view of this, the Guidelines were prepared in such a way as to make them widely informative and minimally prescriptive.

True implementation of the Guidelines requires realization of their full potential by relevant medical professionals. The Guidelines should be interpreted at a national level to reflect local healthcare organization, cultural background and socioeconomic situations.

Health providers may wrongly assume that the management of hypertension can be easily addressed in a just a few, brief visits, and can be tempted to reimburse accordingly. Policy-makers should develop comprehensive prevention programs that will guarantee full reimbursement and eradicate the view of guidelines as a means to reducing cost – a misconception that can lead to reimbursement being limited to high-risk conditions defined by arbitrary cutoffs.

References

- AmarJChamontinBGenesNWhy is hypertension so frequently uncontrolled in secondary prevention?J Hypertens200321119920512777958

- AmbrosioniEPharmacoeconomic challenges in disease management of hypertensionJ Hypertens200119Suppl 3S3340

- ArimaHChalmersJWoodwardMLower target blood pressures are safe and effective for the prevention of recurrent stroke: the PROGRESS trialJ Hypertens2006241201816685221

- Asia Pacific Cohort Studies CollaborationJoint effects of systolic blood pressure and serum cholesterol on cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific regionCirculation200511233849016301345

- AssmannGSchulteHThe Prospective Cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study: prevalence of hyperlipidemia in persons with hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus and the relationship to coronary heart diseaseAm Heart J19881161713243202078

- BlacherJStaessenJAGirerdXPulse pressure not mean pressure determines cardiovascular risk in older hypertensive patientsArch Intern Med20001601085910789600

- BobrieGChatellierGGenesNCardiovascular prognosis of “masked hypertension” detected by blood pressure self-measurement in elderly treated hypertensive patientsJAMA20042911342915026401

- BurtVLCutlerJAHigginsMTrends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the Health Examination Surveys, 1960 to 1991Hypertension1995266097607734

- CollinsRPetoRMacMahonSBlood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological contextLancet1990335827391969567

- CollinsRMacMahonSBlood pressure, antihypertensive drug treatment and the risk of stroke and of coronary heart diseaseBr Med Bull199450272988205459

- CriquiMHLangerRDFronekAMortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial diseaseN Engl J Med199232638161729621

- DekkerJMGirmanCRhodesTMetabolic syndrome and 10-year cardiovascular disease risk in the Hoorn StudyCirculation20051126667316061755

- DickersonJEHingoraniADAshbyMJOptimisation of antihypertensive treatment by crossover rotation of four major classesLancet199935320081310376615

- DickinsonHOMasonJMNicolsonDJLifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomised controlled trialsJ Hypertens2006242153316508562

- DicksteinKKjekshusJOPTIMAAL Steering Committee of the OPTIMAAL Study GroupEffects of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL randomised trial. Optimal Trial in Myocardial Infarction with Angiotensin II Antagonist LosartanLancet20023607526012241832

- DollRPetoRWheatleyKMortality in relation to smoking: 40 years’ observations on male British doctorsBr Med J1994309901117755693

- DomanskiMJMitchellGFNormanJEIndependent prognostic information provided by sphygmomanometrically determined pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure in patients with left ventricular dysfunctionJ Am Coll Cardiol199933951810091821

- DunderKLindLZetheliusBIncrease in blood glucose concentration during antihypertensive treatment as a predictor of myocardial infarction: population based cohort studyBr Med J200332668112663403

- ESH/ESC Hypertension Practice Guidelines CommitteePractice guidelines for primary care physicians: 2003 ESH/ESC hypertension guidelinesJ Hypertens20032117798614508180

- ESH/ESC Hypertension Practice Guidelines Committee2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial HypertensionJ Hypertens20072511058717563527

- EzzatiMLopezADRodgersASelected major risk factors and global and regional burden of diseaseLancet200236013476012423980

- FagardRHStaessenJAThijsLResponse to antihypertensive treatment in older patients with sustained or nonsustained systolic hypertensionCirculation200010211394410973843

- FagardRHExercise characteristics and the blood pressure response to dynamic physical trainingMed Sci Sports Exerc200133S4849211427774

- FagardRHCelisHPrognostic significance of various characteristics of out-of-the-office blood pressureJ Hypertens2004221663615311089

- FagardRHVan Den BroekeCDe CortPPrognostic significance of blood pressure measured in the office, at home and during ambulatory monitoring in older patients in general practiceJ Hum Hypertens2005a198010715959536

- FagardRHBjornstadHHBorjessonMESC Study Group of Sports Cardiology recommendations for participation in leisure-time physical activities and competitive sports for patients with hypertensionEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil2005b123263116079639

- FreemantleNClelandJYoungPBeta blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysisBMJ19993181730710381708

- GasowskiJFagardRHStaessenJAPulsatile blood pressure component as predictor of mortality in hypertension: a meta-analysis of clinical trial control groupsJ Hypertens2002201455111791038

- GirmanCJRhodesTMercuriMThe metabolic syndrome and risk of major coronary events in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) and the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS)Am J Cardiol2004931364114715336

- HaffnerSMLehtoSRonnemaaTMortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med1998339229349673301

- HansenTWJeppesenJRasmussenSAmbulatory blood pressure monitoring and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population based studyAm J Hypertens2006192435016500508

- HanssonLZanchettiACarruthersSGEffects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trialLancet19983511755629635947

- HaynesRBMcDonaldHPGargAXHelping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applicationsJAMA20022882880312472330

- JenningsGLExercise and blood pressure: Walk, run or swim?J Hypertens19971556799218174

- Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood PressureReport: a cooperative studyJAMA197723725561576159

- Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood PressureThe 1980 ReportArch Intern Med1980140128056775608

- KannelWBBlood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor: prevention and treatmentJAMA1996275157168622248

- KannelWBWolfPABenjaminEJLevyDPrevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimatesAm J Cardiol1998822N9N

- KannelWBRisk stratification in hypertension: new insights from the Framingham StudyAm J Hypertens200013Suppl 1S3S10

- KearneyPMWheltonMReynoldsKGlobal burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide dataLancet20053652172315652604

- KhattarRSSeniorRLahiriACardiovascular outcome in white-coat versus sustained mild hypertension. A 10-year follow-up studyCirculation199898189279799210

- KilanderLNymanHBobergMHypertension is related to cognitive impairment: A 20-year follow-up of 999 menHypertension19983178069495261

- KlagMJWheltonPKRandallBLBlood pressure and end-stage renal disease in menN Engl J Med19963341387494564

- KnowlerWCSartorGMelanderAScherstenBGlucose tolerance and mortality, including a substudy of tolbutamide treatmentDiabetologia19974068069222648

- LakkaHMLaaksonenDELakkaTAThe metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged menJAMA200228827091612460094

- LaunerLJMasakiKPetrovitchHThe association between midlife blood pressure levels and late-life cognitive function. The Honolulu-Asia Aging StudyJAMA19952741846517500533

- LaurentSCockcroftJVan BortelLExpert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applicationsEur Heart J20062725880517000623

- LawMREpidemiologic evidence on salt and blood pressureAm J Hypertens199710Suppl 5S425

- LeeVCRhewDCDylanMMeta-analysis: angiotensin-receptor blockers in chronic heart failure and high-risk acute myocardial infarctionAnn Intern Med200414169370415520426

- LevyDLarsonMGVasanRSThe progression from hypertension to congestive heart failureJAMA19962751557628622246

- MacMahonSPetoRCutlerJBlood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution biasLancet1990335765741969518

- ManciaGAmbrosioniEAgabiti-RoseiEBlood pressure control and risk of stroke in untreated and treated hypertensive patients screened from clinical practice: results of the ForLife studyJ Hypertens20052315758116003185

- ManciaGParatiGBorghiCHypertension prevalence, awareness, control and association with metabolic abnormalities in the San Marino population: the SMOOTH studyJ Hypertens2006a248374316612244

- ManciaGFacchettiRBombelliMLong-term risk of mortality associated with selective and combined elevation in office, home, and ambulatory blood pressureHypertension2006b478465316567588

- ManciaGBombelliMCorraoGMetabolic syndrome in the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study: daily life blood pressure, cardiac damage, and prognosisHypertension2007a4940717130308

- ManciaGBousquetPElghoziJLThe sympathetic nervous system and the metabolic syndromeJ Hypertens2007bin press

- MansonJETostesonHRidkerPMThe primary prevention of myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med19923261406161533273

- MartiniukALLeeCMLawesCMHypertension: its prevalence and population-attributable fraction for mortality from cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific regionJ Hypertens20072573917143176

- MorganTOAndersonAIMacInnisRJACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, calcium blockers, and diuretics for the control of systolic hypertensionAm J Hypertens200114241711281235

- MuleGNardiECottoneSInfluence of metabolic syndrome on hypertension-related target organ damageJ Intern Med20052575031315910554

- Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research GroupRelationship between baseline risk factors and coronary heart disease and total mortality in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research GroupPrev Med198615254733749007

- NidesMOnckenCGonzalesDSmoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-upArch Intern Med20061661561816908788

- OhkuboTKikuyaMMetokiHPrognosis of masked hypertension and white-coat hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoringJ Am Coll Cardiol2005465081516053966

- PATS Collaborative GroupPost-stroke antihypertensive treatment studyChin Med J199510871078575241

- PfefferMAMcMurrayJJVelazquezEJValsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or bothN Engl J Med20033491893614610160

- PROGRESS Collaborative Study GroupRandomised trial of perindopril based blood pressure-lowering regimen among 6108 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attackLancet200135810334111589932

- Prospective Studies CollaborationAge-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studiesLancet200236019031312493255

- PuddeyIBBeilinLJRakieVAlcohol, hypertension and the cardiovascular system: a critical appraisalAddiction Biol1997215970

- ResnickHEJonesKRuotoloGInsulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic American Indians: the Strong Heart StudyDiabetes Care200326861712610050

- RosenbergLKaufmanDWHelmrichSPShapiroSThe risk of myocardial infarction after quitting smoking in men under 55 years of ageN Engl J Med1985313151144069159

- SacksFMSvetkeyLPVollmerWMEffects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research GroupN Engl J Med200134431011136953

- SandvikLErikssenJThaulowEPhysical fitness as a predictor of mortality among healthy, middle-aged Norwegian menN Engl J Med199332853378426620

- SchmidtMIDuncanBBBangHIdentifying individuals at high risk for diabetes: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities studyDiabetes Care2005282013816043747

- ShekellePGRichMWMortonSCEfficacy of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-blockers in the management of left ventricular systolic dysfunction according to race, gender, and diabetic status: a meta-analysis of major clinical trialsJ Am Coll Cardiol20034115293812742294

- SilagyCMantDFowlerGLodgeMMeta-analysis on efficacy of nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessationLancet1994343139427904003

- SkoogILernfeltBLandahlS15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementiaLancet1996347114158609748

- StaessenJAGasowskiJWangJGRisks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trialsLancet20003558657210752701

- StamlerJVaccaroONeatonJDWentworthDDiabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention TrialDiabetes Care199316434448432214

- StringerWWWassermanKStatement on exercise: American College of Chest Physicians/American Thoracic Society–exercise for fun or profit?Chest20051271072315764797

- ThomasFRudnichiABacriAMCardiovascular mortality in hypertensive men according to presence of associated risk factorsHypertension20013712566111358937

- TonstadSFarsangCKlaeneGBupropion SR for smoking cessation in smokers with cardiovascular disease: a multicentre, randomised studyEur Heart J2003249465512714026

- VasanRSLarsonMGLeipEPAssessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort studyLancet2001a3581682611728544

- VasanRSLarsonMGLeipEPImpact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular diseaseN Engl J Med2001b3451291711794147

- VasanRSBeiserASeshadriSResidual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart StudyJAMA200228710031011866648

- VerdecchiaPReboldiGPAngeliFShort- and long-term incidence of stroke in white-coat hypertensionHypertension200545203815596572

- WannametheeSGShaperAGPatterns of alcohol intake and risk of stroke in middle-aged British menStroke199627103398650710

- WeiMMitchellBDHaffnerSMSternMPEffects of cigarette smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol, and hypertension on all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart StudyAm J Epidemiol19961441058658942437

- WHO/FAOJoint WHO/FAO Expert report on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic disease. Executive Summary [online]2003 Accessed 15 July 2007. URL: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/trs916/summary/en/index.html

- Wolf-MaierKCooperRSBanegasJRHypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United StatesJAMA20032892363912746359

- YapYGDuongTBlandJMPrognostic value of blood pressure measured during hospitalization after acute myocardial infarction: an insight from survival trialsJ Hypertens2007253071317211237

- ZanchettiAHanssonLMenardJRisk assessment and treatment benefit in intensively treated hypertensive patients of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) studyJ Hypertens2001198192511330886