Abstract

Background. In cancer cells, metabolism is shifted to aerobic glycolysis with lactate production coupled with a higher uptake of glucose as the main energy source. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) catalyzes the reduction of pyruvate to form lactate, and serum level is often raised in aggressive cancer and hematological malignancies. We have assessed the prognostic value of LDH in solid tumors.

Material and methods. A systematic review of electronic databases was conducted to identify publications exploring the association of LDH with clinical outcome in solid tumors. Overall survival (OS) was the primary outcome, and cancer-specific survival (CSS), progression-free survival (PFS), and disease-free survival (DFS) were secondary outcomes. Data from studies reporting a hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were pooled in a meta-analysis. Pooled HRs were computed and weighted using generic inverse-variance and random-effect modeling. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results. Seventy-six studies comprising 22 882 patients, mainly with advanced disease, were included in the analysis. Median cut-off of serum LDH was 245 U/L. Overall, higher LDH levels were associated with a HR for OS of 1.7 (95% CI 1.62–1.79; p < 0.00001) in 73 studies. The prognostic effect was highest in renal cell, melanoma, gastric, prostate, nasopharyngeal and lung cancers (all p < 0.00001). HRs for PFS was 1.75 (all p < 0.0001).

Conclusions. A high serum LDH level is associated with a poor survival in solid tumors, in particular melanoma, prostate and renal cell carcinomas, and can be used as a useful and inexpensive prognostic biomarker in metastatic carcinomas.

The different metabolism of cancer compared with that of normal cells confers a selective advantage for their proliferation and survival. The use of lactate as an energy source requires the conversion of lactate into pyruvate as well as the transport of lactate into and out of tumor cells by specific transporters. The former pathway is regulated by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). LDHs catalyze the conversion of pyruvate and lactate, with concomitant conversion of NADH and NAD+. These enzymes are homo- or hetero-tetramers composed of a M and a H protein subunits that are encoded by LDHA and LDHB genes, respectively. LDHA and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) are up-regulated in solid tumors in response to hypoxia in a HIF-1α-dependent manner. LDHA reducing the pyruvate into lactate regenerates the NAD+ pool necessary to maintain an adequate glycolytic process. The combinations of LDHA and LDHB proteins into tetramers result in the five major isoforms of LDH, numbered 1–5. LDH-5 has the highest efficiency to catalyze the conversion of pyruvate to lactate. LDH-5 is mainly localized to the cytoplasm, where it participates in glucose metabolism. Expression of LDHA and increased levels of functionally active LDH-5 are commonly observed events in highly invasive hypoxic cancers that are resistant to chemo- and radiotherapy. Biochemical markers of tumor burden, such as LDH have been incorporated into several prognostic scores and staging for renal cell carcinoma, melanoma and colorectal cancer [Citation1–3]. In metastatic germ cell tumors, furthermore, LDH is incorporated in the IGCCCG prognostic classification, and this possibly aids in guiding treatment and stratifying patients in clinical trials [Citation4].

The significance and magnitude of the prognostic impact of circulating LDH are, however, unclear. LDH might be a simple and inexpensive objective prognostic parameter that could be used in daily oncologic clinical practice, other than helping to stratify patients in clinical trials. The aim of this study was to summarize all data to quantify the prognostic value of LDH on the clinical outcome in various solid tumors, using standard meta-analysis techniques.

Material and methods

This analysis was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [Citation5].

Search methods and criteria for selecting studies for this review

An electronic search of PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Web of Science, CINAHL and the Coch- rane Register of Controlled Trials was performed. Search terms included: (“neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR “neoplasms”[All Fields] OR “cancer”[All Fields]) AND (LDH[All Fields] OR (“l-lactate dehydro- genase”[MeSH Terms] OR (“l-lactate”[All Fields] AND “dehydrogenase”[All Fields]) OR “l-lactate dehydrogenase”[All Fields] OR (“lactate”[All Fields] AND “dehydrogenase”[All Fields]) OR “lactate dehydrogenase”[All Fields])) AND (“mortality” [Subheading] OR “mortality”[All Fields] OR “survival”[All Fields] OR “survival”[MeSH Terms]) AND (multivariate[All Fields] OR (cox[All Fields] AND (“regression (psychology)”[MeSH Terms] OR (“regression”[All Fields] AND “(psychology)”[All Fields]) OR “regression (psychology)”[All Fields] OR “regression”[All Fields]))) AND (hazard[All Fields] AND (“Ratio (Oxf)”[Journal] OR “ratio”[All Fields])). Citation lists of retrieved articles were screened manually to ensure the sensitivity of the search strategy.

Inclusion criteria for the primary analysis were as follows: 1) studies published in complete papers and in the English language, of (at least 10) adult patients with solid tumors reporting on the prognostic impact of serum LDH; and 2) availability of a hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival (OS). For a secondary analysis, studies providing an HR for cancer-specific survival (CSS), progression-free survival (PFS) or time to progression, and disease-free survival (DFS), were included as well. Duplicate publications were excluded. Two reviewers (F. Petrelli, M. Cabiddu) evaluated independently all of the titles identified by the search strategy. The results were then pooled, and all potentially relevant publications were retrieved in full. The same two reviewers then evaluated the complete articles for eligibility. To avoid inclusion of duplicated or overlapping data, we compared author names and institutions where patients were recruited and if substantial doubts remained, the study reporting fewer patients was not included in the analysis.

Data extraction

OS was the primary outcome of interest. CSS, PFS, and DFS were secondary outcomes. The following details were extracted: name of first author, type of study, year of publication, number of patients included in the analysis, disease site, disease stage (non-metastatic, metastatic, mixed [non-metastatic and metastatic]), cut-off defining high LDH, and HRs for OS, PFS, DFS, or CSS as applicable. HRs were extracted only from multivariable analyses. When two or more HRs were reported for different cut-off values, only those above the median LDH value for that study were considered.

Data collection and statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted initially for all included studies for each of the endpoints of interest. Subgroup analyses were conducted for disease site and stage of disease only for the primary outcome. Extracted data were aggregated into a meta-analysis using RevMan 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Estimates of HRs were weighted and pooled using the generic inverse-variance and random-effect model [Citation6]. Analyses were conducted for all studies, and differences between diseases were assessed using methods described by Deeks et al. [Citation7]. Meta-regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of LDH cut-off level (when available) on the HR for OS. Publication bias for the primary endpoint was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot. Heterogeneity was assessed with the use of the Cochran Q and I2 statistics. All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Seventy-six studies [Citation8–83] with a total of 22 882 patients were included (). Characteristics of the included studies are shown in (Supplementary Table I available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1043026); most (95%) were published in the last decade. Among trials, eight studies regarded gastrointestinal malignancies (4 biliopancreatic, 2 gastric, 1 colorectal and 1 neuroendocrine cancers), seven head and neck cancers, seven lung cancers, 12 melanomas, one sarcoma, one thymic carcinoma, one mesothelioma, one breast cancer, four mixed or unknown primaries, 16 prostate cancers, 15 renal cell carcinomas and three testicular cancers. Number of patients ranged from 35 to 2425. In all trials patients with mainly metastatic or locally advanced unresectable disease were included (only 5 trials included stage I–III cancers).

Overall survival

Seventy-three studies reported HR for OS. Forty-one studies did not specify a numerical cut-off used for multivariate analysis; conversely, in 34 studies a predefined cut-off was reported (median: 245 U/L). Twelve of the eligible 73 studies (16%) reported a non-statistically significant HR.

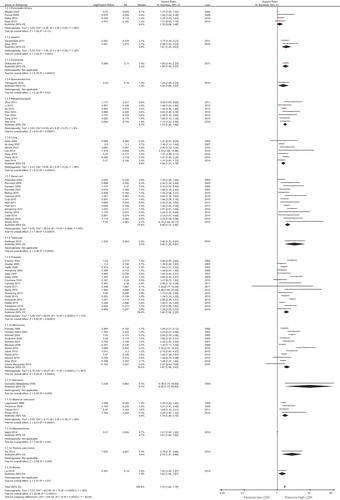

Overall, LDH level was associated with a HR for OS of 1.7 (95% CI 1.62–1.79; p < 0.00001; I2 = 92%, p for heterogeneity < 0.00001, random-effect model). The effect of LDH level on OS among disease subgroups is shown in . The prognostic effect of serum LDH, among subgroups with two or more studies, was highest in renal cell carcinoma (HR = 2.08; 95% CI 1.74–2.5, p < 0.00001), followed by melanoma (HR = 1.97; 95% CI 1.59–2.43, p < 0.00001), gastric cancer (HR = 1.91; 95% CI 1.38–2.63, p < 0.0001), prostate cancer (HR = 1.9; 95% CI 1.58–2.29, p < 0.00001), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (HR = 1.74; 95% CI 1.52–1.99, p < 0.00001), and lung cancer (HR = 1.54; 95% CI 1.33–1.78, p < 0.00001). The HR for the subgroup of mixed solid tumors series or unknown primary was 1.74 (95% CI 1.4–2.15, p < 0.00001). Differences between disease subgroups were statistically significant (p for subgroup difference < 0.00001). Neuroendocrine tumors, breast cancer, thymic carcinoma, mesothelioma, testicular and colorectal cancer, and sarcoma data were provided only in one paper each.

Figure 2. Forest plots showing hazard ratio for overall survival for LDH greater than or less than the cut-off for overall studies and by disease subgroups.

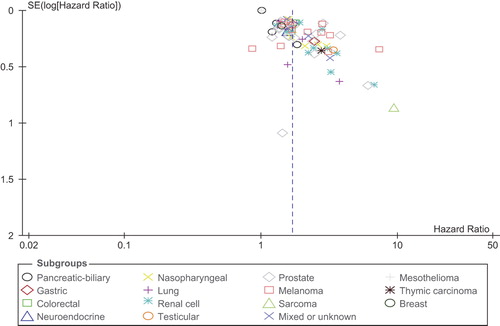

For the 15 disease-site subgroups analyzed, there was statistically significant heterogeneity among trials of biliopancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, and melanoma, whereas heterogeneity among other trials was non-statistically significant. The scatter plot for the meta-regression is shown in (Supplementary Figure 1 available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1043026). Overall, there was a nearly statistically significant association between LDH cut-off and the HR for OS (p = 0.11). There was evidence of significant publication bias, with several studies reporting significantly higher results than expected ().

Cancer-specific survival

Few studies reported this data, so a formal meta-analysis was not performed.

Progression-free survival or time to progression

Thirteen trials reported HRs for PFS or TTP. Overall, a high LDH level was associated with a poor PFS (HR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.31–2.33, p < 0.0001; I2 = 86%, p for heterogeneity < 0.0001, random-effect model).

Disease-free survival

Only two studies including nasopharyngeal cancer patients reported HRs for DFS. A high LDH concentration was associated with a lower DFS as multivariate analysis (HR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.24–2.27, p = 0.001; I2 = 47%, p for heterogeneity = 0.16, fixed effect model).

Discussion

Several studies have suggested that elevated LDH is both a hallmark of aggressive carcinomas and lymphomas and associated with an unfavorable outcome. Indeed, LDH levels are actually included in the TNM staging system for melanoma [Citation3], defining the M1c subgroup that is associated with a five-year OS of 10%. LDH is also considered with respect to the risk status of testicular cancer, in particular metastatic non-seminoma germ cell tumors [Citation84].

We performed a meta-analysis of 76 studies involving 22 882 patients with solid tumors in order to assess the prognostic effect of serum LDH. We found a consistent impact of elevated LDH on survival (HR = 1.7) among various disease subgroups, and mainly in advanced disease stages. High serum LDH was also associated with a reduced PFS in 13 trials. As expected, the magnitude of the effect on OS was the greatest in melanoma and renal cell carcinoma other than metastatic (castration-resistant) prostate cancer. The burden of the data considered (about 50% of the included studies) concerns these neoplastic diseases, in which hypoxia and angiogenic factors play a crucial role. In particular, in renal cell carcinoma, a five-parameter-based prognostic score provided by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center that is commonly used in patients with metastatic disease includes LDH levels and correlates these with outcomes in patients treated in various clinical trials before and after the era of targeted therapy [Citation85,Citation86]. The present analysis mainly covered patients with advanced tumors, which confirms that the prognostic role of LDH currently seems to be confined to only highly proliferative and metastatic cancers. We focused on solid tumors, because the prognostic role of LDH in hematological disease is well known, especially in high-grade lymphoma where it is elevated in almost 50% of patients [Citation87]. The novelty of our data is that it particularly relates to prostate cancer, where the role of LDH as a prognostic factor has not yet been fully demonstrated. Several papers reporting the role of inflammation parameters (neutrophil-lympocyte ratio and C-reactive protein) other than bone-related biomarkers (e.g. alkaline phosphatase) have recently been published [Citation88–94]. In particular, LDH seems to be associated with a poor prognosis in metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer, and could thus be valuable for identifying patients who are suitable for the earlier use of chemotherapy. Data on LDH levels and inflammatory parameters could be useful when starting therapy for prostate cancer and the other metastatic malignancies examined in this meta-analysis. It is possible that C-reactive protein reflects the enhanced immune response elicited by a tumor, which is more intense when tissue necrosis (and so LDH) and inflammation are high, as occurs with more aggressive cancer subtypes.

That lactates play a role in cancer cells is unsurprising, and LDH concentrations in human serum during neoplastic conditions can be regarded as a marker of (cancer) the metabolic activity and avid glucose uptake of cells. Tumor hypoxia actually induces, among other things, the expression of a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), which is a transcription factor that initiates a range of activities, including angiogenesis and various prosurvival mechanisms [Citation95]. In terms of tumor growth, the local blood supply becomes inadequate, thus requiring angiogenesis and leading to hypoxia. The metabolism of cells is consecutively shifted towards the anerobic glycolytic pathway (e.g. from glucose to lactate) through the enhanced expression of glycolytic enzymes and glucose transporters. This is coupled with a reduced dependence on the oxidative pathway. Cancers are also able to produce lactate due to increased glycolytic activity, regardless of oxygen availability (the so-called Warburg effect), which is a phenomenon that was first described about a century ago as being a consequence of energy requests from tumor cells. Lactate which is the end product of glycolysis from pyruvate, is produced in large amounts in highly aggressive tumors in response to the specific characteristics of the microenvironment and the genetic features of neoplastic cells. Importantly, lactate also constitutes an alternative metabolic source for cancer cells [Citation96–98]. The LDH-A gene promoter possesses two conserved hypoxia response elements containing functionally-essential binding sites for HIF-1 with the consensus sequence 5′-RCGTG-3′, which may strongly suggest an oxygen-dependent regulation of LDH-5 activity [Citation99].

Recently, high LDH levels have been found to predict the response to anti-angiogenetic agents, such as bevacizumab and sorafenib. In two papers, Scartozzi et al. examined this predictive role, demonstrating that: 1) in subjects with high serum LDH, bevacizumab confers a higher RR in colorectal cancer; and 2) in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib, LDH levels seem to predict clinical outcomes in terms of PFS and OS [Citation100,Citation101].

This meta-analysis does, however, have some limitations. First, only published data, as opposed to individual patient data, have been collected. Second, we found evidence of high heterogeneity among the trials, as well as a significant publication bias, with a larger number of trials than expected reporting a significantly higher effect of LDH levels. Furthermore, we only included studies reporting HRs, while more than 20 publications reporting on the prognostic value of LDH were excluded (e.g. because only odds ratios, relative risk for survival, or p for significance were reported), possibly introducing bias. It is notable that almost all of the excluded papers (the majority analyzing genitourinary tumors, sarcomas, melanomas and lung cancers) presented a significant association with outcome, thus reducing the risk that could have changed the final results. Many other case series, however, were excluded because serum LDH data was unavailable in the population analyzed. Third, LDH is influenced by other non-neoplastic conditions, including heart failure, hypothyroidism, anemia, and lung or liver disease, which may have influenced the serum concentrations. Most of the studies included in this meta-analysis did not explicitly control for such different, benign conditions that may have affected LDH levels. Finally, a cut-off value associated with a significantly worse OS cannot be defined, even if the median of the reported cut-off values is the common upper normal limit used in most laboratories (245 U/L). Unfortunately, only about 50% of the papers considered provided details of such a cut-off point, and the metaregression for correlations of serum cut-off levels with HRs was not significant. However, to our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to systematically confirm the poor prognostic value of high LDH concentrations in solid tumors. It also involves 22 961 patients included in 76 published studies, mainly concerning genitourinary and melanoma tumors. The value of the analysis does, however, remain confined to advanced tumors with locally advanced and metastatic disease, and its significance with respect to the early stages of disease requires further evaluation.

Recent in vitro studies have shown that inhibiting LDHA expression may lessen invasiveness and the metastatic potential of cancer cells by reducing their proliferation capacity and reversing their resistance to chemotherapy [Citation102–110]. LDH can thus be regarded as an ideal target for anticancer therapies.

In conclusion, serum LDH is associated with poor survival with respect to many solid tumors, and could be used as a cost-effective prognostic biomarker in terms of prognostic scores before treating advanced disease and enrolling patients in prospective trials. The evaluation of LDH as a therapeutic target is also warranted, and is the subject of ongoing trials.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Figure 1 and Table I available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1043026.

ionc_a_1043026_sm3028.pdf

Download PDF (71.6 KB)Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2530–40.

- Chibaudel B, Bonnetain F, Tournigand C, Bengrine-Lefevre L, Teixeira L, Artru P, et al. Simplified prognostic model in patients with oxaliplatin-based or irinotecan-based first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: A GERCOR study. Oncologist 2011;16:1228–38.

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Atkins MB, Buzaid AC, Cascinelli N, Coit DG, et al. An evidence-based staging system for cutaneous melanoma. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:131–49; quiz 182–4.

- International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: A prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:594–603.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100.

- Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. [cited 2014 Dec]. http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook.

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors). Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated 2011 Mar; cited 2014 Dec]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- Zhao Z, Han F, Yang S, Hua L, Wu J, Zhan W. The clinicopathologic importance of serum lactic dehydrogenase in patients with gastric cancer. Dis Markers 2014;140913.

- Wu JX, Chen HQ, Shao LD, Qiu SF, Ni QY, Zheng BH, et al. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factors for advanced thymic carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e324.

- Liu X, Meng QH, Ye Y, Hildebrandt M, Gu J, Wu X. Prognostic significance of pretreatment serum levels of albumin, LDH and total bilirubin in patients with non-metastatic breast cancer. Carcinogenesis Epub 2015;36:243–8.

- Najmi K, Khosravi A, Seifi S, Emami H, Chaibakhsh S, Radmand G, et al. Clinicopathologic and survival characteristics of malignant pleural mesothelioma registered in hospital cancer registry. Tanaffos 2014;13:6–12.

- Ulas A, Turkoz FP, Silay K, Tokluoglu S, Avci N, Oksuzoglu B, et al. A laboratory prognostic index model for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 2014;9:e114471.

- Ferraldeschi R, Nava Rodrigues D, Riisnaes R, Miranda S, Figueiredo I, Rescigno P, et al. PTEN protein loss and clinical outcome from castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone acetate. Eur Urol 2015;67:795–802.

- Zeng L, Tian YM, Huang Y, Sun XM, Wang FH, Deng XW, et al. Retrospective analysis of 234 nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with distant metastasis at initial diagnosis: Therapeutic approaches and prognostic factors. PLoS One 2014;9:e108070.

- Templeton AJ, Pezaro C, Omlin A, McNamara MG, Leibowitz-Amit R, Vera-Badillo FE, et al. Simple prognostic score for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with incorporation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. Cancer 2014;120:3346–52.

- Yamaguchi T, Machida N, Morizane C, Kasuga A, Takahashi H, Sudo K, et al. Multicenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy for advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system. Cancer Sci 2014;105:1176–81.

- Kang MH, Go SI, Song HN, Lee A, Kim SH, Kang JH, et al. The prognostic impact of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2014;111:452–60.

- Wei Z, Zeng X, Xu J, Duan X, Xie Y. Prognostic value of pretreatment serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase in nonmetastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Single-site analysis of 601 patients in a highly endemic area. Oncol Targets Ther 2014;7:739–49.

- Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Armstrong AJ, Clarke SJ, Vardy JL, Templeton AJ, et al. Prognostic impact of the neutrophil- to-lymphocyte ratio in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2014;12:317–24.

- Wang X, Jiang R, Li K. Prognostic significance of pretreatment laboratory parameters in combined small-cell lung cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014;69:633–40.

- Halabi S, Lin CY, Kelly WK, Fizazi KS, Moul JW, Kaplan EB, et al. Updated prognostic model for predicting overall survival in first-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:671–7. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1387.

- Gaudy-Marqueste C, Archier E, Grob A, Durieux O, Loundou A, Richard MA, et al. Initial metastatic kinetics is the best prognostic indicator in stage IV metastatic melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:1120–4.

- Pinato DJ, Stavraka C, Flynn MJ, Forster MD, O’Cathail SM, Seckl MJ, et al. An inflammation based score can optimize the selection of patients with advanced cancer considered for early phase clinical trials. PLoS One 2014;9:e83279.

- Lee J, Kim JO, Jung CK, Kim YS, Yoo IeR, Choi WH, et al. Metabolic activity on [18f]-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography and glucose transporter-1 expression might predict clinical outcomes in patients with limited disease small-cell lung cancer who receive concurrent chemoradiation. Clin Lung Cancer 2014;15:e13–21.

- Amato RJ, Flaherty A, Zhang Y, Ouyang F, Mohlere V. Clinical prognostic factors associated with outcome in patients with renal cell cancer with prior tyrosine kinase inhibitors or immunotherapy treated with everolimus. Urol Oncol 2014;32:345–54.

- Cetin B, Afsar B, Deger SM, Gonul II, Gumusay O, Ozet A, et al. Association between hemoglobin, calcium, and lactate dehydrogenase variability and mortality among metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int Urol Nephrol 2014;46:1081–7.

- Armstrong AJ, Häggman M, Stadler WM, Gingrich JR, Assikis V, Polikoff J, et al. Long-term survival and biomarker correlates of tasquinimod efficacy in a multicenter randomized study of men with minimally symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:6891–901.

- Tian YM, Zeng L, Wang FH, Liu S, Guan Y, Lu TX, et al. Prognostic factors in nasopharyngeal carcinoma with synchronous liver metastasis: A retrospective study for the management of treatment. Radiat Oncol 2013;8:272.

- Gray MR, Martin del Campo S, Zhang X, Zhang H, Souza FF, Carson WE 3rd, et al. Metastatic melanoma: Lactate dehydrogenase levels and CT imaging findings of tumor devascularization allow accurate prediction of survival in patients treated with bevacizumab. Radiology 2014;270:425–34.

- Atkinson BJ, Kalra S, Wang X, Bathala T, Corn P, Tannir NM, et al. Clinical outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with alternative sunitinib schedules. J Urol 2014;191:611–8.

- Kamba T, Yamasaki T, Teramukai S, Shibasaki N, Arakaki R, Sakamoto H, et al. Improvement of prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center intermediate risk features by modern strategy including molecular-targeted therapy in clinical practice. Int J Clin Oncol 2014;19:505–15.

- Powles T, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Kramar A, Lorch A, Beyer J. Prognostic impact of LDH levels in patients with relapsed/refractory seminoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013;139:1311–6.

- Wan XB, Wei L, Li H, Dong M, Lin Q, Ma XK, et al. High pretreatment serum lactate dehydrogenase level correlates with disease relapse and predicts an inferior outcome in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:2356–64.

- Wevers KP, Kruijff S, Speijers MJ, Bastiaannet E, Muller Kobold AC, Hoekstra HJ. S-100B: A stronger prognostic biomarker than LDH in stage IIIB-C melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:2772–9.

- Haas M, Heinemann V, Kullmann F, Laubender RP, Klose C, Bruns CJ, et al. Prognostic value of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, LDH and bilirubin levels in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: Results from a multicenter, pooled analysis of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013;139:681–9.

- Omlin A, Pezaro C, Mukherji D, Mulick Cassidy A, Sandhu S, Bianchini D, et al. Improved survival in a cohort of trial participants with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer demonstrates the need for updated prognostic nomograms. Eur Urol 2013;64:300–6.

- Jin Y, Ye X, Shao L, Lin BC, He CX, Zhang BB, et al. Serum lactic dehydrogenase strongly predicts survival in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with palliative chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1619–26.

- Almasi CE, Drivsholm L, Pappot H, Høyer-Hansen G, Christensen IJ. The liberated domain I of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor – a new tumour marker in small cell lung cancer. APMIS 2013;121:189–96.

- Armstrong AJ, George DJ, Halabi S. Serum lactate dehydrogenase predicts for overall survival benefit in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3402–7.

- Weide B, Elsässer M, Büttner P, Pflugfelder A, Leiter U, Eigentler TK, et al. Serum markers lactate dehydrogenase and S100B predict independently disease outcome in melanoma patients with distant metastasis. Br J Cancer 2012;107:422–8.

- Li G, Gao J, Tao YL, Xu BQ, Tu ZW, Liu ZG, et al. Increased pretreatment levels of serum LDH and ALP as poor prognostic factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer 2012;31:197–206.

- Jakob JA, Bassett RL Jr, Ng CS, Curry JL, Joseph RW, Alvarado GC, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer 2012;118:4014–23.

- Zhou GQ, Tang LL, Mao YP, Chen L, Li WF, Sun Y, et al. Baseline serum lactate dehydrogenase levels for patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A predictor of poor prognosis and subsequent liver metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:e359–65. Erratum in: Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;86:213.

- Chibaudel B, Bonnetain F, Tournigand C, Bengrine-Lefevre L, Teixeira L, Artru P, et al. Simplified prognostic model in patients with oxaliplatin-based or irinotecan-based first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: A GERCOR study. Oncologist 2011;16:1228–38.

- Abel EJ, Culp SH, Tannir NM, Tamboli P, Matin SF, Wood CG. Early primary tumor size reduction is an independent predictor of improved overall survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with sunitinib. Eur Urol 2011;60:1273–9.

- Narita S, Tsuchiya N, Yuasa T, Maita S, Obara T, Numakura K, et al. Outcome, clinical prognostic factors and genetic predictors of adverse reactions of intermittent combination chemotherapy with docetaxel, estramustine phosphate and carboplatin for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2012;17:204–11.

- Zhang HL, Zhu Y, Wang CF, Yao XD, Zhang SL, Dai B, et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate kinetics as a marker of treatment response and predictor of prognosis in Chinese metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Int J Urol 2011;18:422–30.

- Trédan O, Ray-Coquard I, Chvetzoff G, Rebattu P, Bajard A, Chabaud S, et al. Validation of prognostic scores for survival in cancer patients beyond first-line therapy. BMC Cancer 2011;11:95.

- Kume H, Suzuki M, Fujimura T, Fukuhara H, Enomoto Y, Nishimatsu H, et al. Docetaxel as a vital option for corticosteroid-refractory prostate cancer. Int Urol Nephrol 2011;43:1081–7.

- Sougioultzis S, Syrios J, Xynos ID, Bovaretos N, Kosmas C, Sarantonis J, et al. Palliative gastrectomy and other factors affecting overall survival in stage IV gastric adenocarcinoma patients receiving chemotherapy: A retrospective analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2011;37:312–8.

- Yamada Y, Nakamura K, Aoki S, Tobiume M, Zennami K, Kato Y, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase, Gleason score and HER-2 overexpression are significant prognostic factors for M1b prostate cancer. Oncol Rep 2011;25:937–44.

- Richey SL, Culp SH, Jonasch E, Corn PG, Pagliaro LC, Tamboli P, et al. Outcome of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy without cytoreductive nephrectomy. Ann Oncol 2011;22:1048–53.

- Gerlinger M, Wilson P, Powles T, Shamash J. Elevated LDH predicts poor outcome of recurrent germ cell tumours treated with dose dense chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2913–8.

- Patil S, Figlin RA, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Négrier S, Kim ST, et al. Prognostic factors for progression-free and overall survival with sunitinib targeted therapy and with cytokine as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2011; 22:295–300.

- Culp SH, Tannir NM, Abel EJ, Margulis V, Tamboli P, Matin SF, et al. Can we better select patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma for cytoreductive nephrectomy? Cancer 2010;116:3378–88.

- Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Kogure H, Hirano K, et al. Impact of S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:774–80.

- Staudt M, Lasithiotakis K, Leiter U, Meier F, Eigentler T, Bamberg M, et al. Determinants of survival in patients with brain metastases from cutaneous melanoma. Br J Cancer 2010;102:1213–8.

- Coumans FA, Doggen CJ, Attard G, de Bono JS, Terstappen LW. All circulating EpCAM+ CK+ CD45- objects predict overall survival in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1851–7.

- Vermaat JS, van der Tweel I, Mehra N, Sleijfer S, Haanen JB, Roodhart JM, et al. Two-protein signature of novel serological markers apolipoprotein-A2 and serum amyloid alpha predicts prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer and improves the currently used prognostic survival models. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1472–81.

- González-Billalabeitia E, Hitt R, Fernández J, Conde E, Martínez-Tello F, Enríquez de Salamanca R, et al. Pre-treatment serum lactate dehydrogenase level is an important prognostic factor in high-grade extremity osteosarcoma. Clin Transl Oncol 2009;11:479–83.

- Furuse J, Okusaka T, Ohkawa S, Nagase M, Funakoshi A, Boku N, et al. A phase II study of uracil-tegafur plus doxorubicin and prognostic factors in patients with unresectable biliary tract cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009;65:113–20.

- Scher HI, Jia X, de Bono JS, Fleisher M, Pienta KJ, Raghavan D, et al. Circulating tumour cells as prognostic markers in progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: A reanalysis of IMMC38 trial data. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:233–9.

- Trivanović D, Petkovic M, Stimac D. New prognostic index to predict survival in patients with cancer of unknown primary site with unfavourable prognosis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21:43–8.

- Neuman HB, Patel A, Ishill N, Hanlon C, Brady MS, Halpern AC, et al. A single-institution validation of the AJCC staging system for stage IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:2034–41.

- Saito T, Hara N, Kitamura Y, Komatsubara S. Prostate-specific antigen/prostatic acid phosphatase ratio is significant prognostic factor in patients with stage IV prostate cancer. Urology 2007;70:702–5.

- Escudier B, Choueiri TK, Oudard S, Szczylik C, Négrier S, Ravaud A, et al. Prognostic factors of metastatic renal cell carcinoma after failure of immunotherapy: New paradigm from a large phase III trial with shark cartilage extract AE 941. J Urol 2007;178:1901–5.

- de Jong WK, Fidler V, Groen HJ. Prognostic classification with laboratory parameters or imaging techniques in small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2007;8:376–81.

- Humphrey PA, Halabi S, Picus J, Sanford B, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ, et al. Prognostic significance of plasma scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor levels in patients with metastatic hormone- refractory prostate cancer: Results from cancer and leukemia group B 150005/9480. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2006;4:269–74.

- Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1997–2005.

- Schmidt H, Johansen JS, Gehl J, Geertsen PF, Fode K, von der Maase H. Elevated serum level of YKL-40 is an independent prognostic factor for poor survival in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer 2006;106:1130–9. Erratum in: Cancer 2006;107:2315.

- Peccatori J, Barkholt L, Demirer T, Sormani MP, Bruzzi P, Ciceri F, et al. European Bone Marrow Transplantation Solid Tumor Working Party. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma undergoing nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Cancer 2005;104:2099–103.

- D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Cox MC, Dahut W, Figg WD. Prostate-specific antigen response duration and risk of death for patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 2005;66:571–6.

- Taplin ME, George DJ, Halabi S, Sanford B, Febbo PG, Hennessy KT, et al. Prognostic significance of plasma chromogranin a levels in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer treated in Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9480 study. Urology 2005;66:386–91.

- Schmidt H, Bastholt L, Geertsen P, Christensen IJ, Larsen S, Gehl J, et al. Elevated neutrophil and monocyte counts in peripheral blood are associated with poor survival in patients with metastatic melanoma: A prognostic model. Br J Cancer 2005;93:273–8.

- Soubrane C, Rixe O, Meric JB, Khayat D, Mouawad R. Pretreatment serum interleukin-6 concentration as a prognostic factor of overall survival in metastatic malignant melanoma patients treated with biochemotherapy: A retrospective study. Melanoma Res 2005;15:199–204.

- George DJ, Halabi S, Shepard TF, Sanford B, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ, et al. The prognostic significance of plasma interleukin-6 levels in patients with metastatic hormone- refractory prostate cancer: Results from cancer and leukemia group B 9480. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:1815–20.

- Masaki T, Ohkawa S, Amano A, Ueno M, Miyakawa K, Tarao K. Noninvasive assessment of tumor vascularity by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and the prognosis of patients with nonresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 2005;103:1026–35.

- Ando S, Suzuki M, Yamamoto N, Iida T, Kimura H. The prognostic value of both neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and Cyfra21-1 in small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2004;24:1941–6.

- Chiarion-Sileni V, Del Bianco P, De Salvo GL, Lo Re G, Romanini A, Labianca R, et al. Italian Melanoma Intergroup (IMI). Quality of life evaluation in a randomised trial of chemotherapy versus bio-chemotherapy in advanced melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:1577–85.

- Atzpodien J, Royston P, Wandert T, Reitz M; DGCIN – German Cooperative Renal Carcinoma Chemo-Immunotherapy Trials Group. Metastatic renal carcinoma comprehensive prognostic system. Br J Cancer 2003;88:348–53.

- Lagerwaard FJ, Levendag PC, Nowak PJ, Eijkenboom WM, Hanssens PE, Schmitz PI. Identification of prognostic factors in patients with brain metastases: A review of 1292 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;43:795–803.

- Franzke A, Probst-Kepper M, Buer J, Duensing S, Hoffmann R, Wittke F, et al. Elevated pretreatment serum levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and lactate dehydrogenase as predictors of survival in cutaneous metastatic malignant melanoma. Br J Cancer 1998;78:40–5.

- Fosså SD, Oliver RT, Stenning SP, Horwich A, Wilkinson P, Read G, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with advanced seminoma treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:1380–7.

- van Dijk MR, Steyerberg EW, Habbema JD. Survival of non-seminomatous germ cell cancer patients according to the IGCC classification: An update based on meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:820–6.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:289–96.

- Motzer RJ, Bukowski RM, Figlin RA, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Kim ST, et al. Prognostic nomogram for sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2008;113:1552–8.

- Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: Clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2780–95.

- Scher HI, Heller G, Molina A, Attard G, Danila DC, Jia X, et al. circulating tumor cell biomarker panel as an individual-level surrogate for survival in metastatic castration- resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol Epub 2015 Mar 23. pii: JCO.2014.55.3487.

- Taverna G, Pedretti E, Di Caro G, Borroni EM, Marchesi F, Grizzi F. Inflammation and prostate cancer: Friends or foe? Inflamm Res Epub 2015 Mar 19.

- Langsenlehner T, Pichler M, Thurner EM, Krenn-Pilko S, Stojakovic T, Gerger A, et al. Evaluation of the platelet- to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator in a European cohort of patients with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. Urol Oncol Epub 2015 Mar 10. pii: S1078–1439(15)00062–9.

- Graff JN, Beer TM, Liu B, Sonpavde G, Taioli E. Pooled analysis of C-reactive protein levels and mortality in prostate cancer patients. Clin Genitourin Cancer Epub 2015 Jan 30. pii: S1558–7673(15)00013–0.

- van Soest RJ, Templeton AJ, Vera-Badillo FE, Mercier F, Sonpavde G, Amir E, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: Data from two randomized phase III trials. Ann Oncol 2015;26:743–9.

- Fizazi K, Massard C, Smith M, Rader M, Brown J, Milecki P, et al. Bone-related parameters are the main prognostic factors for overall survival in men with bone metastases from castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2014 Oct 29. pii: S0302–2838(14)01009–4.

- Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, de Wit R, Tannock I, Eisenberger M. Prediction of survival following first-line chemotherapy in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:203–11.

- Denko NC. Hypoxia. HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8:705–13.

- Sonveaux P, Végran F, Schroeder T, Wergin MC, Verrax J, Rabbani ZN, et al. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3930–42.

- Feron O. Pyruvate into lactate and back: From the Warburg effect to symbiotic energy fuel exchange in cancer cells. Radiother Oncol 2009;92:329–33.

- Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Ertel A, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, et al. Evidence for a stromal-epithelial ‘lactate shuttle’ in human tumors: MCT4 is a marker of oxidative stress in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle 2011;10:1772–83.

- Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, Passantino R, Concordet JP, Maire P, et al. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 1996;271:32529–37.

- Faloppi L, Scartozzi M, Bianconi M, Svegliati Baroni G, Toniutto P, Giampieri R, et al. The role of LDH serum levels in predicting global outcome in HCC patients treated with sorafenib: Implications for clinical management. BMC Cancer 2014;14:110.

- Scartozzi M, Giampieri R, Maccaroni E, Del Prete M, Faloppi L, Bianconi M, et al. Pre-treatment lactate dehydrogenase levels as predictor of efficacy of first-line bevacizumab-based therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2012;106:799–804.

- Xie H, Hanai J, Ren JG, Kats L, Burgess K, Bhargava P, et al. Targeting lactate dehydrogenase – a inhibits tumorigenesis and tumor progression in mouse models of lung cancer and impacts tumor-initiating cells. Cell Metab 2014;19:795–809.

- Liu X, Yang Z, Chen Z, Chen R, Zhao D, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of the suppression of lactate dehydrogenase A on the growth and invasion of human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2015;33:157–62.

- Xie H, Valera VA, Merino MJ, Amato AM, Signoretti S, Linehan WM, et al. LDH-A inhibition, a therapeutic strategy for treatment of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8:626–35.

- Zhou M, Zhao Y, Ding Y, Liu H, Liu Z, Fodstad O, et al. Warburg effect in chemosensitivity: Targeting lactate dehydrogenase-A re-sensitizes taxol-resistant cancer cells to taxol. Mol Cancer 2010;9:33.

- Zhai X, Yang Y, Wan J, Zhu R, Wu Y. Inhibition of LDH-A by oxamate induces G2/M arrest, apoptosis and increases radiosensitivity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep 2013;30:2983–91.

- Gupta GS. LDH-C4: A target with therapeutic potential for cancer and contraception. Mol Cell Biochem 2012;371: 115–27.

- Wang ZY, Loo TY, Shen JG, Wang N, Wang DM, Yang DP, et al. LDH-A silencing suppresses breast cancer tumorigenicity through induction of oxidative stress mediated mitochondrial pathway apoptosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;131:791–800.

- Fantin VR, St-Pierre J, Leder P. Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis, mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell 2006;9:425–34. Erratum in: Cancer Cell 2006;10:172.

- Granchi C, Roy S, Giacomelli C, Macchia M, Tuccinardi T, Martinelli A, et al. Discovery of N-hydroxyindole-based inhibitors of human lactate dehydrogenase isoform A (LDH-A) as starvation agents against cancer cells. J Med Chem 2011;54: 1599–612.