Abstract

Background: Locking catheter with heparin may increase bleeding risk of some hemodialysis (HD) patients. Hence, the security and effectivity of 10% concentrated sodium chloride (CSC) used as an alternative method for patients with high bleeding risk need to be investigated. Methods: Seventy-two patients inserted temporary central venous catheters were divided into two groups randomly. A total of 3125 U/mL heparin saline (HS) was used in HS group and 10% CSC in CSC group to lock catheters. Heparin-free HD was used for the first time and plasma specimens were collected to test coagulation indicators before catheter-locking (at the end of HD) and at 30 min after it. Then, blood flow velocities (BFVs), incidences of catheter thrombosis, etc. were followed up at each time of HD. Results: Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of two groups had no difference at the end of heparin-free HD (27.100 [25.675–28.950] vs. 27.250 [25.150–29.575] second, p = 0.933), but at 30 minutes after using different catheter lock solutions, APTT of HS group was obviously longer than CSC group (50.100 [41.275–65.400] vs. 27.500 [25.525–29.875] second, p < 0.001). Catheters’ retaining time of two groups were the same (p = 0.306), so did the average BFVs (p > 0.05). But catheters’ thrombosis incidence and urokinase usage of HS group were less than CSC group (p < 0.05). Conclusion: Comparing with HS group, thrombosis incidences of CSC group increased, but catheters’ retaining time and average BFVs remained the same and coagulation indicators of it were unaffected. Therefore, it can be an effective alternative lock method for HD patients with high bleeding risk.

Introduction

As facing bleeding risk frequently, hemodialysis (HD) patients need heparin-free HD to lower the risk. However, for patients with central venous catheters (CVC), benefits of heparin-free HD will be cancelled out because of the heparin locked in their catheters after HD which may increase bleeding risk through overflowing into blood,Citation1–5 or even raise bleeding events significantly.Citation6 Therefore, locking catheter with heparin is not a safe and ideal method for patients with high bleeding risk.

Inspired by the idea of locking CVC with high concentration citrate, we designed and applied a new catheter lock solution which was 10% concentrated sodium chloride (CSC), and evaluated its security and effectivity through a prospective randomized controlled trail, so as to provide a low bleeding risk catheter lock method for clinical use.

Patients and methods

Patients

Seventy-two acute or chronic renal failure patients were enrolled. All of them received internal jugular or subclavian veins catheterizations with temporary CVC and their HD treatments at Department of Nephrology, the First Affiliated Hospital of PLA General Hospital from August 2011 to April 2012. Gender and age of them were unlimited, but patients suffering from obvious active bleeding, heparin allergy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or severe hypernatremia and hyperchloremia (Na >160 mmol/L or Cl >120 mmol/L) were excluded before enrollment because of worrying about catheter lock solution-related complications of heparin or CSC after randomly grouping.

Study design

It is a prospective randomized controlled trail. Following random numbers produced by statistical software, the patients were divided into two groups based on enrolling time, and applied 36 cases as CSC group (locking catheters with 10% CSC), 36 cases as heparin saline (HS) group (locking catheters with 1:1 HS which concentration is 3125 U/mL). All patients were treated with 4008B dialysis machines (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Deutschland), F12/F14 polysulfone membrane dialyzer (Weigao Blood Purification Products Co., Ltd, Weihai, China), and bicarbonate dialysate (Ziweishan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Hebei, China) during observation period.

The first time of HD treatment for patients was heparin-free HD. Before the treatment, closed loop was connected with dialyzer and pipeline, 0.005% HS (50 mg heparin was added into 1000 mL saline) was prefilled into the loop to adsorb at last 20 min, and then drained with 500 mL saline. In all, 2 mL catheter lock solution (more than all inserted catheters’ volume) was removed from each lumen of CVC when HD started. During the treatment, the blood flow velocity (BFV) was maintained at 220–300 mL/minute and pipeline was rinsed with 150 mL saline every 30 min in order to check clotting status until the end of HD. After HD, 10 mL saline was injected into each lumen of CVC to rinse blood thoroughly through a pulse style. Then, in accordance with the marked volume, CVC was locked slowly with CSC or HS abiding by grouping strictly. At the following HD treatments, heparin or low molecular heparin could be used as anticoagulant, but heparin-free HD might be restored according to changes of condition at any time. Each patient’s CVC was kept on locking with pre-specified grouping strictly and the method had been mentioned above.

If some patients got aforementioned conditions of exclusion criteria during observation period, they would be withdrawn and excluded. Extubation (owing to dysfunction, infection, changing fistula or tunneled cuffed catheter) was defined as end point. Transfer with CVC or withdrawal were seen as loss to follow-up.

Observed indicators

Demographic data, such as gender, age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), catheterization time, inserting site, type of CVC and dose of oral antihypertensive drugs were recorded when patients enrolled. Furthermore, hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (HCT), platelet (PLT), albumin (ALB), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by MDRD equation, serum sodium (Na), chlorine (Cl) and coagulation indicators, such as prothrombin time (PT), prothrombin activity (YHDD), international normalized ratio (INR) and APTT were determined before catheterization.

Average BFV of CVC (mean of all recorded BFVs in HD) was measured, and plasma specimens were collected to determine the four coagulation indicators mentioned above at the end of first time of HD (before catheter-locking, from pipeline) and 30 min after it (from venous). Then, average BFVs of catheters continued to be measured in the following HD. Pre-HD blood pressure, Hb, HCT, PLT, Na, Cl, and doses of oral antihypertensive drugs were recorded as censored data at the end of observation period or at the time of loss to follow-up. All incidents including bleeding, thrombosis, dysfunction, and infection of CVC were recorded with the occurrence time throughout observation period as well.

Statistical analyses

All quantitative data were analyzed by normality test. Data conforming to it was expressed as mean ± standard deviation and t-test was used to compare the differences between groups. Data not conforming to normal distribution or without clear range was expressed as median & (25–75% percentile) and rank sum test was used. Qualitative data was expressed as n (percentage %) and Pearson Chi-square test was used. Furthermore, referring to survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare the difference of CVC retaining time. All analyses were calculated with software SPSS 17.0 and p < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance of data.

Results

Comparisons of baseline data between two observed groups

All the clinical data of the two groups including coagulation indicators were matched with each other ().

Table 1. Comparisons of baseline data between two observed groups.

Comparisons of bleeding risk before and after catheter-locking between two observed groups

There was no difference between the coagulation indicators of two groups after heparin-free HD (before catheter-locking). However, growth of PT, APTT and reduction of YHDD of HS group were more obvious than CSC group through reexamination at 30 min after catheter-locking (p < 0.05). Differences between the two groups were more significant if statistics was applied with the differences between various time points and the baseline (p < 0.001). In brief, APTT of CSC group was changeless, but median of APTT of HS group extended by 22.45 s (about 80%) when compared with baseline ().

Table 2. Comparisons of coagulation indicators before and after catheter-locking at the end of heparin-free HD between two observed groups.

Comparisons of temporary CVCs’ retaining time and patency between two observed groups

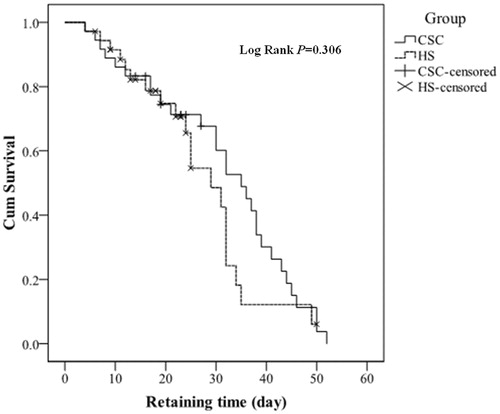

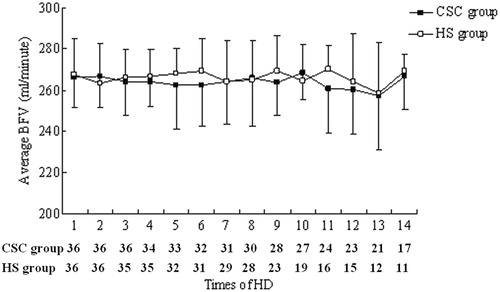

Median CVCs’ retaining time of CSC group was 28.5 days and HS group was 20.5 days. The time of CSC group was longer (p = 0.029). But the difference was not found when CVCs’ retaining time of two groups was counted through Kaplan–Meier method (p = 0.306, ). In addition, there was no difference between average BFVs of two groups which were measured in each time of HD, too (p > 0.05, ).

Figure 1. Comparisons of temporary CVCs’ retaining time between two observed groups. CSC, concentrated sodium chloride; HS, heparin saline.

Figure 2. Comparisons of temporary CVCs’ retaining time between two observed groups. CSC, concentrated sodium chloride; HS, heparin saline. BFV, blood flow velocity. The remaining cases of each group corresponding to the times of HD were listed under the figure, and average BFVs were calculated with the data of remaining cases. At every time point, p values of average BFVs were >0.05.

Comparisons of censored data and adverse events between two observed groups

By comparing censored data, we could not find the difference of blood pressure, serum Na, PLT, and so on between the two groups. But serum Cl of CSC group was about 2 mmol/L higher than HS group (p = 0.037, ).

Table 3. Comparisons of censored data between two observed groups.

Results of adverse events () suggested that: (1) CVCs’ thrombotic incidents and usage of urokinase in CSC group were more than those in HS group (42.650% vs. 27.596%, and 6.832% vs. 3.552%). Both of the comparisons could be considered as statistical significance (p < 0.05). Only one catheter was extubated because of dysfunction, but it occurred in HS group. (2) Although some minor bleeding incidents happened in both groups during follow-up, the impacts of using heparin in HD could not be ruled out, and there was no difference between bleeding incidents of two groups (p = 0.343). (3) No catheter-related infection occurred in both groups. Therefore, comparison was not done.

Table 4. Comparisons of adverse events between two observed groups during the follow-up period.

Discussion

As an important vascular access for HD, CVC is clinically used worldwide. According to 2010 Annual Data Report of USRDS, proportion of patients who were inserted temporary CVCs for their first HD was up to 55–89%, while proportion of the ones who selected tunneled cuffed CVC as long-term vascular access also maintained at 17–18% during recent years.Citation7 The most common method to ensure patency of CVCs is locking them with heparin whose concentration is from 1000 U/mL to 10,000 U/mL presently. Different units use different concentration and there is no unified standard.Citation8 In theory, concentration of heparin need not to be limited strictly for most of HD patients without bleeding risk as long as catheter’s patency is ensured. On the other hand, the patients with high bleeding risk must be clearly distinguished from general HD ones and need to be more cautious while locking catheters with heparin.

As early as 2001, bleeding complications related to locking catheter with heparin had been reported.Citation1 Since that, scholars have confirmed through in vitro tests that catheter lock solution would overflow from CVC either with marked volume lock or with reduced volume lock. The overflow proportion would be 18–30%Citation2 or even up to 40% in some articles.Citation3 It also has been found by in vivo studies that about 12–31.3% of catheter lock solution would overflow from different types of catheters 10 min after locking with 5000 U/mL HS.Citation4 That is about 2400–4500 U of heparin which equal to injecting a large dose of heparin before HD. We subsequently used a more diluted concentration (3125 U/mL) of HS to lock CVCs in a study and discovered that APTT of 30 min after catheter-locking extended 66.7% longer than the baseline. Even after removing and discarding the last HS catheter lock solution, the left heparin attaching to the wall of lumens could have anticoagulant effect at start of HD and APTT of 5 min after starting HD was also extended by 13.6% longer than the baseline.Citation5 Therefore, the overflowing heparin from catheter is an important reason of increased bleeding risk after HD. If HD patients are at perioperative period or undergoing definite active hemorrhage, only receiving heparin-free HD is not enough and the catheter lock method must be improved as well.

American Diagnostic and Interventional Society of Nephrology recommended that locking catheter with low concentration (1000 U/mL) HS or 4% citrate was the method with relatively lower bleeding risk.Citation8 It is also a way to explore some new alternative lock solutions. For example, Twardowski had used acidified (pH 2.0) 27% CSC and “air-bubble method” to lock catheter for anti-infection, but a certain amount of heparin was still injected to the catheter tip.Citation9 However, topical anticoagulant capacity of CSC due to its hypertonic characteristic must be ignored by the study. Inspired by previous clinical usage of trisodium citrate lock solution whose concentration is 30%,Citation10,Citation11 or even up to 46%,Citation12,Citation13 we propose that 10% CSC might be used as catheter lock solution whose Na concentration is 1.711 mol/L and only equivalent to 16.8% of trisodium citrate. CSC is not an anticoagulant and will not increase bleeding risk even overflowing into circulation. So, it would be a safer catheter lock method for patients with high bleeding risk.

Our study evaluated this new alternative catheter lock method because it is not only very cheap (2 mL heparin is about 11 times more expensive than 10 mL 10% CSC. Even if the cost of urokinase was counted, price of locking catheters with HS is still as twice as CSC), but also more accessible than citrate lock solution and easier to be popularized. Through the study, we believe that 10% CSC lock solution has following characteristics when compared with 3250 U/mL HS: (1) Variation extent of coagulation indicators before and after catheter-locking, such as prolongation of APTT of CSC group is significantly less than the one of HS group. The difference can only be explained by the different kinds of lock solution because plasma specimens were collected at heparin-free HD. So locking CVC with CSC is safer for HD patients with high bleeding risk. (2) Though thrombotic incidents of CVCs and usage of urokinase in CSC group are much more during observation period, its CVCs’ retaining time and average BFVs are not inferior to HS group. So CSC can be used to lock CVC for over a period (e.g., 2–3 weeks) and is enough to help patients overcome the period with high bleeding risk. (3) Although CSC has been used, there is no difference of blood pressure, Na and oral antihypertensive drugs (species) between the different groups. But after locking catheters with CSC for a period, serum Cl concentration is a bit higher than the other group. However, the mean value (101.731 mmol/L) is still in the normal range. As a result, CSC is a safe alternative catheter lock method which can be chosen by the patients with high bleeding risk.

Since we have not found any literatures related to CSC lock solution, its anticoagulant principle still cannot be definitively explained in this article. It can only be speculated that high osmotic pressure may lead to dysfunction of contacted blood cells (including PLT), or cause coagulation factors (mainly proteins) salted out or denatured. It will result in coagulation disorder in and near the lumens. Furthermore, the characteristic of high osmotic pressure may be useful for inhibiting growth of bacterial in the lumens so as to achieve the purpose of nonspecific anti-infection.Citation14 Moreover, patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) may also benefit from the use of CSC. However, these inferences still need to be confirmed by further studies.

There are several shortcomings in our research. For example, the reason to choose 10% CSC is only because the preparation is such a concentration. Also, the possibility of contamination would increase if confecting step was added to produce 3% CSC which is clinically allowed to drip intravenously. And we didn’t spend much time to consider whether lower concentration CSC was a better lock solution. But this topic is worth to be examined and continued to investigate.

In summary, overflowing heparin lock solution will cause obvious coagulation disorder for HD patients with CVC after their treatment and increase their bleeding risk. Receiving heparin-free HD and CSC as an alternative lock solution after HD would be effective method to avoid bleeding risk.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Karaaslan H, Peyronnet P, Benevent D, Lagarde C, Rince M, Leroux-Robert C. Risk of heparin lock-related bleeding when use indwelling venous catheter in hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2072–2074

- Sungur M, Eryuksel E, Yavas S, Bihorac A, Layon AJ, Caruso L. Exit of catheter lock solutions from double lumen acute hemodialysis catheters-an in vitro study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3533–3537

- Agharazii M, Plamondon I, Lebel M, Douville P, Desmeules S. Estimation of heparin leak into the systemic circulation after central venous catheter heparin lock. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1238–1240

- Markota I, Markota D, Tomic M. Measuring of the heparin leakage into the circulation from central venous catheters-an in vivo study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1550–1553

- Chen FK, Li JJ, Chen P, Zhao CZ, Gong HY, Yao DH. The effect of heparin saline used for catheter locking after heparin-free dialysis on coagulation parameters in patients with high bleeding risk. Chin J Blood Purif. 2012;11:245–248

- Yevzlin AS, Sanchez RJ, Hiatt JG, et al. Concentrated heparin lock is associated with major bleeding complications after tunneled hemodialysis catheter placement. Semin Dial. 2007;20:351–354

- National Institutes of Health NIDDK/DKUHD. USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report, volume two: atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2010:270–284

- Moran JE, Ash SR; ASDIN Clinical Practice Committee. Locking solutions for hemodialysis catheters; heparin and citrate–a position paper by ASDIN. Semin Dial. 2008;21:490–492

- Twardowski ZJ, Reams G, Prowant BF, Moore HL, Van Stone JC. Air-bubble method of locking central-vein catheters for prevention of hub colonization: a pilot study. Hemodial Int. 2003;7:320–325

- Stas KJ, Vanwalleghem J, De Moor B, Keuleers H. Trisodium citrate 30% vs. heparin 5% as catheter lock in the interdialytic period in twin- or double-lumen dialysis catheters for intermittent hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;6:1521–1522

- Weijmer MC, van den Dorpel MA, Van de Ven PJ, et al. Randomized, clinical trial comparison of trisodium citrate 30% and heparin as catheter-locking solution in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2769–2777

- Venditto M, du Montcel ST, Robert J, et al. Effect of catheter-lock solutions on catheter-related infection and inflammatory syndrome in hemodialysis patients: heparin versus citrate 46% versus heparin/gentamicin. Blood Purif. 2010;29:268–273

- Winnett G, Nolan J, Miller M, Ashman N. Trisodium citrate 46.7% selectively and safely reduces staphylococcal catheter-related bacteraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3592–3598

- Oguzhan N, Pala C, Sipahioglu MH, et al. Locking tunneled hemodialysis catheters with hypertonic saline (26% NaCl) and heparin to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections and thrombosis: a randomized, prospective trial. Ren Fail. 2012;34:181–188