Abstract

A major research project, conducted in the United States, examined the effects of leadership at multiple levels on student learning. Although that study resulted in a book (Leithwood & Louis, Citation2011), further analysis provides additional insights into the way in which formal and informal leaders function in schools. These additional analyses have not previously been synthesized to illuminate how school leaders can make a difference in the lives of children. The purpose of this paper is to provide one perspective on this question, focusing in particular on findings that may be applicable in the Nordic context.

Does educational leadership matter? In one sense, a simple answer to that question is yes, and a review of the research addressing the empirical evidence was covered more than a decade ago (Leithwood, Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, Citation2004). The simple conclusion also contains an important and well-accepted codicil: Although leaders affect a variety of educational outcomes, their impact on students is largely indirect and is relatively small compared to other factors. While formal leaders interact with pupils in many circumstances, the impact of schooling on students occurs largely through more sustained relationships that occur in classrooms and peer groups.

On the other hand, a simple, albeit conditional, yes is insufficient to address the more fundamental question: What is the range of effects that leadership may have on pupils, classrooms and schools? Or, put another way, whose leadership matters for what kinds of outcomes? This paper summarizes recent research that addresses the slightly more complex questions and focuses on different sources of leadership and how they ‘trickle down’ to shape the conditions of student learning. I present no new data, but draw from analyses that have been published or are in press elsewhere. However, my effort to synthesise ideas from previous research is new and based on emerging areas of inquiry that should, I argue, receive additional attention in the coming years.

This paper also builds on several premises. First, educational reform policies that are prevalent both in the United States and elsewhere are grounded in a research tradition that privileges the role of teachers to the exclusion of other social actors in and out of schools. The mantra that ‘teachers account for most of the variation in the impact of schools on student learning’ is so firmly established in the mind of the public that other considerations are often pushed aside as secondary. This situation is hardly surprising, because an emphasis on teacher effects has a personal resonance with researchers as well as the public:

The transformative power of an effective teacher is something almost all of us have experienced and understand on a personal level …. We know intuitively that these highly effective teachers can have an enriching effect on the daily lives of children and their lifelong educational and career aspirations. (Tucker & Stronge, Citation2005, p. 1, italics added)

The intuitive response, in addition to an accumulation of research on effective teaching over several years, reinforces the importance of teacher quality. However, it has often led to a narrow focus on teachers as solo practitioners of a skilled craft rather than examining teaching and learning as an organisational phenomenon.

In addition, research that is used to justify a policy emphasis on teacher quality in some countries is derived primarily from older studies in two states (Texas and Tennessee) and correlational studies in the United States and other countries. Although a parallel line of research on effective schools has also gained significant traction in the professional media as well as in scholarly journals, the focus of school effects studies has often been on structural characteristics (Jack Lam, Citation2005), and one of the most recent reviews called for increased emphasis on teachers rather than on the school's organization (Reynolds et al., Citation2014).Footnote1 This paper, in contrast, points to a few promising conclusions that show that leadership should be given more consideration in school effectiveness research and that it can make a difference in student learning. Leadership has an influence largely through the design of the school's normative structure and culture, including the following:

A focus on ‘no silos’, or an emphasis on leadership from multiple levels and across multiple organizational units

Efforts to strengthen how adults in schools work together in professional communities

Using leader influence to shape productive school cultures – cultures that are associated with student learning

DistrictFootnote2 practices that support school leaders in developing productive school cultures

Translating research: the importance of context

Social science research, even when experimentally designed, will always be culturally situated. This fact is particularly true for education, because countries (and even regions within countries) vary in how systems are designed, what the public, parents and students expect from them, and how people interpret the social meaning of a term that might appear on the surface to be uniform (such as teacher quality or school quality). The promising conclusions that I discuss here are based almost exclusively on research that has been carried out in the United States, although there have been some replications of findings in other settings. I have chosen to emphasise findings that are potentially applicable in other countries, while acknowledging that this will require both additional research and a more sensitive interpretation of their meaning if they are to be applied in different cultural and political contexts. In particular, since I am writing for a Scandinavian audience, it is important to acknowledge some of the ways in which we are alike and unalike. Based on comparative studies of organizational and work culture, Scandinavian countries and the United States share some important features that affect how schools operate (Hofstede, Citation2001). First, citizens of the Nordic countries, like Americans, tend to be relatively open to change and risk-taking in their personal and organizational lives – at least as compared to those who live in more traditional cultural settings. Second, our countries respect expertise, but also expect relatively close working relationships and opportunities to challenge those who are in positions of formal authority. Although there are some differences among the Nordic countries on these dimensions, they are more like each other than other members of the European community. Finally, people in both the United States and the Nordic countries tend to look at their work and their lives with a perspective that focuses neither on the very long term (what will life be like for me in 20 years) nor on the short term (will I be rewarded today or tomorrow). All of these perspectives affect the way in which people work with each other and what they expect to be able to do with students in a school.

There are, however, some consistent differences in Hofstede's work (Hofstede, Citation1991, Citation2001; Hofstede, Neuijen, Ohayv, & Sanders, Citation1990) that also seem ‘real’ to me based on my association with many colleagues (and relatives) in Scandinavia. These differences also affect how educators see their work. The United States, for example, represents an extremely individualistic culture that also places a high value on work rewards related to success or promotion. Scandinavian work values, in contrast, focus on the quality of relationships and a sense of comfort in work and are more interested in collective success.

We should not place too much emphasis on simple descriptions of cultural difference or similarity. In particular, educators and schools have their own culture, which distinguishes them from other kinds of work settings (Firestone & Louis, Citation2000; Toole, Louis, & Hargreaves, Citation1999). For example, in all countries it is expected that schools will create consistency in educational experiences for students – too much variety in what is expected from year to year or school to school violates what parents and communities want. Schools are also expected to support important cultural goals that are rarely explicitly identified, such as encouraging students to become ‘good Norwegian citizens’ or ‘good Americans’. Teacher selection and preparation vary somewhat between countries, but in all countries it is assumed that people who are drawn to the profession will see intrinsic value in fostering the development of others and will generally be cooperative and supportive of a stable and caring environment for children. People who become and remain educators are not, therefore, expected to have the same personality profile as high-tech entrepreneurs – whether they are in Finland or in the United States.

As Seymour Sarason noted long ago, the shared culture of the profession is both a strength and also an impediment to change and improvement (Sarason, Citation1971, Citation1996). The impediments emerge because of the relationship between teachers and students, where teachers are assumed to have ‘knowledge’ and to be responsible for posing important questions, students are expected to find answers to questions and ‘the curriculum’ is expected to be the primary source of important questions, even though teachers often view it as a constraint. One recent investigation of mental models of learning in an innovative bilingual school in the United States suggests, for example, that this image of teaching and learning is firmly embedded among primary school students (Felber-Smith, Citation2015). No matter how often we look for the ephemeral ‘zone of proximal development’ or encourage students to actively participate in their own learning, adults still see themselves (and are seen by others) as responsible. As Sarason emphasizes in his later book, ‘The problem of change is the problem of power, and the problem of power is how to wield it in ways that allow others to identify with, to gain a sense of ownership of, the process and goals of change’ (p. 335). It is important, in examining the research results that I present in the rest of this paper, to be sensitive to Sarason's observation, which, I suspect, is as important in Scandinavian countries as it is elsewhere. Although my examinations of the culture of schools and school leadership do not address this directly, I return to Sarason's challenge at the end of this paper.

The linking leadership to learning study

In 2004, the Wallace Foundation funded the University of Minnesota and the University of Toronto to carry out a large-scale, longitudinal study to examine two critical questions:

How do educational leaders influence student learning?

What patterns of leadership, from teachers, principals and district staff, influence the quality of instruction and student learning?

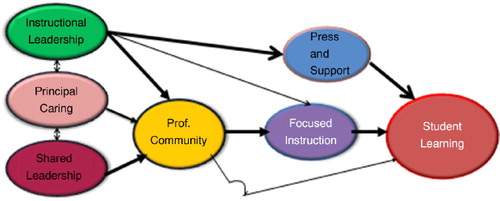

The study, which was very large and complex, used existing literature about school leadership to develop a framework to examine these questions ().

Begun in December of 2004, this mixed-methods project aimed to further our understanding about the nature of successful educational leadership and how such leadership at the school, district and state levels eventually influences teaching and learning in schools. The research design called for the collection of quantitative data at several points in the 5-year effort, with three rounds of qualitative data collection in between. The quantitative data are provided by surveys of teachers and administrators, along with student achievement and demographic data available from the district or state.

The sampling design involved respondents in 180 schools nested within 45 districts nested, in turn, in nine states. These states were randomly sampled from the four quadrants of the United States. Districts and schools were chosen randomly within states, with the sample stratified to reflect variation in organization size, socio-economic status (SES) and achievement trajectories over 3–5 years prior to the start of the data collection. The quantitative sample (schools that responded to the survey instrument in sufficient numbers to be representative) included 157 schools and the teachers and administrators who were members of them. The sample deliberately represented elementary and secondary schools in equal numbers. This paper draws primarily from survey data analyses using both the first and second rounds of data. However, the interpretation of the quantitative results is influenced by the extensive case study analysis that was part of the study and its conclusions.

A summary of the overall work of the project was published as a report and was revised as a book several years ago (Leithwood & Louis, Citation2011; Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, Anderson, & Michlin, Citation2010; see Appendix 1). Like many large projects, the publication of the book was an intermediate stop on the path to answering questions of interest to researchers and practitioners. This paper draws both on chapters that were part of the earlier publications and on work that occurred afterwards, including some that is ongoing. Thus, the key findings that I explicate below do not appear as such in the earlier report or book.

Key result 1: no silos and the need for integrative leadership

There is increasing interest in both the general and educational leadership literature around what is coming to be called integrative leadership (Crosby & Bryson, Citation2010; Moos & Huber, Citation2007). The focus of integrative leadership is on collaboration, particularly collaboration across boundaries that normally create silos. Such boundaries include differences between schools and community agencies or districts, the rather different perspectives that teachers and administrators adopts when looking at school problems and the different perspectives of public and private sector organizations that are part of the school's community (Morse, Citation2010).Footnote3 According to Crosby and Bryson (Citation2010), the key defining feature of integrative leadership is ‘spanning levels, sectors and cultures to help diverse groups remedy the most difficult shared public problems’ (p. 205). In simple terms, integrative educational leaders are agents who link elements within the school or between the school and other groups in order to create connections, bridge differences and therefore provide easier access to new ideas and possibilities.

Referring back to Sarason's (Citation1971, Citation1996) dilemma of power in schools, integrative leaders tend to ignore power in favour of thinking about the goal of improvement. Our boundaries – whether they are between the biology teachers and the language teachers or between parents and the school – keep schools from imagining new ways of doing things. Integrative leadership requires the willingness to take some risks – presumably a culturally compatible expectation in the Nordic countries and the United States – in the interest of benefitting children. This type of leadership also tends to see differences in perspective through a positive lens, emphasising the need to look for novel solutions to persistent educational problems or issues. This inclusive perspective encourages expanding the sphere of influence of different actors with an interest in the outcomes of schooling. Rather than assuming that ‘parents know best’ or that ‘our youth services partners will take care of that problem’, integrative leaders believe that finding and solving a problem in a school may require input from many people, each of whom has different knowledge and resources to bear.

Drawing primarily on the information obtained from multi-year case studies, a conclusion that emerges is that integrative leadership is particularly effective in ensuring that there is an all-school focus to improvement initiatives. In the less effective or ‘stuck’ schools in our study (Rosenholtz, Citation1991), we noticed very early that, even with the increasing pressure for test-based accountability,Footnote4 some principals and districts emphasized comprehensive improvement initiatives that touched all schools and all grades, while others fussed over improving tested performance for students in tested grades and subjects. The schools and districts with a more comprehensive approach to change were more likely to stimulate principals and teachers to develop a clear sense of how they would move forward together (Louis & Robinson, Citation2012). Wahlstrom (Citation2011), in a different paper, analysed the way in which teachers, both in surveys and interviews, described leadership for improvement in their schools and came to three important conclusions: (1) principals who were regarded by their teachers as effective instructional leaders were able to describe, comprehensively, the instructional issues facing their schools; (2) they were actively engaged with all teachers around issues of instruction; and (3) they empowered teachers to take on responsibility for improvement (Wahlstrom, Citation2011, pp. 77–79). What this information suggests is that effective school leader development should emphasise reflective behaviour and action, rather than focusing primarily on enhancing specific leader attributes (knowledge).Footnote5 In addition, reflection should focus on thinking about actions that can be linked with an outcome that is directly related to a social good. Whereas our work focused on better instruction, schools deliver a wide variety of socially valued outcomes that are meaningful to their colleagues and other partners. Louis and Robinson (Citation2012) found that the instructionally effective principals were also particularly effective at working with their districts and were able to negotiate ‘space’ to pursue agendas that were highly motivating to their teachers and parents. In other words, they were skilled at working across boundaries and creating a ‘big picture’ perspective that engaged multiple partners.

Key result 2: the ‘magic’ of professional community

We are not the first to point to the importance of a ‘whole school’ focus (Felner et al., Citation2001; Johnson, Kahle, & Fargo, Citation2007), but many of the existing studies look at the implementation of specialized programs (literacy or bullying) across the whole school rather than ways of engaging all teachers and students around broader improvement goals. Other large studies have suggested that replicating comprehensive programs across a large number of schools requires special magic under conditions of high public pressure, high educator anxiety and high fear of failure (Berends, Bodilly, & Kirby, Citation2002). It is to one element of that magic that I now turn.

The ‘no silos’ message assumes that all people in the school are engaged in thinking about improvement. This assumption runs up against one of the traditional characteristics of school culture in the United States (which are also embedded in many other countries): teachers perform most of their work in isolation, with one teacher in a classroom that contains a relatively large number of pupils. Scholars in the United States have pointed to teacher isolation as one of the features of school culture that makes change hard (Lortie, Citation2002; Sarason, Citation1990, Citation1996). There is some evidence that the Nordic countries are not immune to this problem. For example, the recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Teaching and Learning International Survey suggests that all Nordic countries are below the OECD average in teachers who report that feedback from others improved their practice, and all except Denmark are below average in the percentage of teachers who reported that they mentored other teachers or that they engaged in professional development as a result of feedback.Footnote6 While one survey with limited items does not prove much, it suggests that teacher isolation may be an issue in many Scandinavian schools.

The Linking Leadership to Learning study framework assumed that studying school conditions (see ) meant looking more deeply at teachers’ work, particularly at the way in which leadership could reduce isolation and develop professional community and teacher leadership. Professional community and teacher leadership have, of course, been linked to student learning both conceptually and empirically in some of my previous work with a sample of innovative schools (Louis & Marks, Citation1998; Louis, Marks, & Kruse, Citation1996; Marks & Louis, Citation1997). As defined (and measured), the concept of professional community is very similar to the idea of ‘communities of practice’ (Wenger, Citation1998), but it is more clearly focused on the reinforcement of educational professionalism, which is characterized by a technical knowledge base, institutionalized training, some control over the conditions of professional work and a strong client orientation (Hall, Citation1975; Larson, Citation1978). Some of the characteristics of a school-based professional community are as follows (in rough order of the frequency with which they are found in US schools):

Shared norms and values: The presence of strong, ethically-based and morally binding norms of behaviour.

Collective focus on student learning: Educators emphasise the importance of understanding how well students are learning rather than emphasising their teaching practice. There are shared efforts to assess student learning beyond standardized tests.

Collaboration: Professionals in the school work together to develop new approaches to teaching and learning that reflect their shared values.

Reflective dialogue: Educators engage in deep conversations in which current practices are seen as problematic.

‘De-privatized’ practice: Educators visit each other's classrooms to learn from observation and to provide ideas for reflective dialogue and development (Kruse, Louis, & Bryk, Citation1995).

Professional community should not be confused with the cognate term professional learning communities (PLCs) for a variety of reasons (Louis, Citation2007). PLCs are typically initiated as a change in a school's structure to provide an opportunity for teachers to develop their collective focus on learning, to be more collaborative, and to be reflective. As such, they represent an aspiration for teacher professionalism that breaks down the traditional silos of teachers operating in their own classrooms. However, structural innovations are not always successful, particularly where teachers are assigned to teams and where their problems of practice are identified by someone else. Professional community, as conceived in our study, reflects actual levels of teacher behaviour, whether it occurs in a formal team or informally.

Our study affirms what was found in several previous smaller scale studies (Langer, Citation2000; Lomos, Hofman, & Bosker, Citation2011; Louis & Marks, Citation1998; Newmann, Marks, & Gamoran, Citation1996): the higher the reported level of professional community experienced by teachers, the more likely they are to demonstrate more effective teaching practices (Wahlstrom & Louis, Citation2008) and the more likely they are to report a positive academic climate in their buildings (Louis & Lee, in press). What is significant about this finding is that the most effective teaching strategies were those that combined elements of direct instruction (which assumes a traditional power relationship between teacher and pupil) and constructivist instruction (which assumes that students bears some responsibility for defining and ensuring effective learning) (Wahlstrom & Louis, Citation2008). Newmann et al.'s (Citation1996) analysis suggests that this is also reflected in student's reports of their experience of supportive classroom settings as well as higher academic achievement.

Key result 3: school leadership shapes productive school cultures

More importantly for the topic of this paper, our findings show that teachers’ reports of their principal's leadership behaviors are strongly associated with the presence of higher levels of professional community as well as the quality of their teaching (Louis & Lee, in press). We also found that principals’ influence over professional community allowed them to have a strong, statistically significant (indirect) impact on student learning (Louis, Dretzke, & Wahlstrom, Citation2010). In particular, teachers report that principals who exercise stronger instructional leadership, who make more concerted efforts to engage teachers in making critical decisions about school improvement and who provide an environment that supports them as individuals are also more likely to experience solid professional relationships with their peers and colleagues (Louis & Lee, in press; Louis, Murphy, & Smylie, Citation2014; Wahlstrom & Louis, Citation2008).

What does this mean in practice? Interviews with both principals and teachers (in addition to survey items) suggest that principals who foster professional community among teachers act in very specific ways: they observe classrooms and ask questions that provoke teachers to think; they give ‘power’ over curriculum priorities and school practices to teachers; they consult teachers before making most important decisions; they ensure that all students have equal opportunity to have the best teachers; they use staff meetings to talk about equity and instruction, not about procedures; and they ask all teachers to observe each other's classrooms. In other words, teachers assess the effects of their principals by pointing to specific behaviors rather than generalised personality characteristics.

summarizes, across a variety of analyses, how principals affect teachers’ experience of their colleagues and how that translates into better teaching. What the figure suggests is twofold: (1) instructional leadership, shared leadership and demonstrated caring for teachers are all important predictors of teachers’ experience of more robust professional communities, which in turn affect the quality of their teaching; and (2) instructional leadership from the principal has an additional important relationship to the school's cultural emphasis on providing students with both pressure to be academically engaged (press), and support for students who may be falling behind or have more difficulty in school (support). These, in turn, predict the school's relative performance on standardized achievement tests. Our data suggest that balancing academic pressure and academic support are particularly important in schools with a larger percentage of low income, immigrant or minority pupils (Lee & Louis, Citation2012).

There is additional evidence about the integrative behaviors of effective school leaders that are associated with improvements in the school. These behaviors involve a more detailed understanding of how school leaders shape the relationship that the school has with new ideas and knowledge. One focus that has developed considerable traction in educational research over the past few years is that of organizational learning. This is embodied in the idea of PLCs, which point to the importance of getting and using information that will help to improve current practice in a school. Some authors have suggested that professional communities are most likely to develop when teachers interact seriously with new information obtained through professional development, reading groups or action research (Louis & Leithwood, Citation1998; Schön, Citation1987; Scribner, Cockrell, Cockrell, & Valentine, Citation1999; Scribner, Hager, & Warn, Citation2002). What happens in teacher conversations about their practice may be unimportant if it is not informed by a search for information that stimulates discussions about incremental change.

Organizational learning can be generated in many ways. We asked, for example, how many teachers in this school show initiative to identify and solve problems? How many teachers in this school seek out and read current findings in educational research? How many teachers in this school share current findings in education with colleagues? Did you discuss what you learned from professional development with other people? Have you tried out new ideas in your classroom? We, like others who have studied teacher learning and teacher culture on a smaller scale, find that where teachers report being engaged in professional communities they also report (1) that they and their colleagues are searching for, discussing, assessing and trying to use new ideas, and (2) are more likely to have effective teaching practices and higher student learning (Louis & Lee, in press). This represents the willingness to take risks in practice that are critical to creating a professional community that learns and reinforces continuous improvement. Our research suggests that schools that have an organizational learning culture emphasise both collaboration and adaptation:

A collaborative culture emphasizes strong, mutually reinforcing exchanges and linkages between teachers and departments and policies, procedures, standards and tasks that are designed to encourage teamwork and camaraderie. Teachers see themselves as ‘leaders’ and ‘owners’ of the culture rather than employees.

An adaptive culture involves active monitoring of the environment (typically by the school leader) and policies and practices that support the school's ability to respond to opportunities or avoid threats. Teachers and leaders actively engage the community and parents, and members take risks by experimenting with new practices.

Key result 4: local education authorities make a difference

The study found that local education authorities (districts in the United States) play critical integrative leadership roles. All too often local agencies are thought to have a particular responsibility for monitoring and compliance to ensure quality and, in substantially decentralized systems such as the United States and the Nordic countries, to have responsibility for setting targets for improvement for individual schools as well as distributing resources to meet the goals (DuFour & Fullan, Citation2013; Knudson, Shambaugh, & O'Day, Citation2011; Marsh, Strunk, & Bush, Citation2013). Evidence on the effectiveness of systemic reform strategies that focus on districts is only beginning to emerge (Honig & Rainey, Citation2015), and it was not our primary focus. Our study, in contrast to Honig and Rainey's work, emphasized district leadership behaviors rather than looking at systemic reform initiatives, and we found that several were particularly important in fostering school and student development.

First, districts played a critical role in stimulating integrative leadership by developing policies and expectations about community and parent engagement at the school level (Gordon, Citation2010; Gordon & Louis, Citation2011). Where districts did not have specific policies and expectations, community and parent engagement were either absent or low (as reported by school leaders). This factor turned out to be important because additional analysis showed that parent engagement was high in those schools where school leaders and teachers had high levels of shared leadership (as reported by teachers) and where principals perceived parent involvement to be high. Parent involvement in our study (like many others) was associated with student learning. In sum, where districts set expectations for involvement, it was more likely to occur; where it occurred, principals and teachers were more engaged with parents and students apparently responded to the stronger joint expectations sent by the multiple adults in their lives (Gordon & Louis, Citation2009).

However, district actions are important for school leader work in other ways as well. Districts that help school leaders feel more efficacious about school improvement work have positive effects on school conditions and student learning (Leithwood and Louis, Citation2011, p. 116). In addition, school leaders who believe they are working collaboratively with district personnel, other principals, and teachers in their schools are more confident in their leadership, more likely to involve others, and more likely to be leading effective schools (Leithwood and Louis, Citation2011, pp. 23–24).

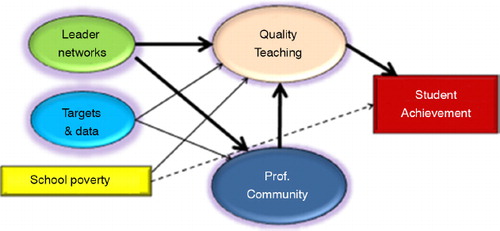

Our case studies suggested that districts could be sources of pressure for principals (when they set targets and evaluated school leader performance on the basis of improvements in test scores) and also sources of support (by providing professional development opportunities and mentors and creating principal networks within the district where principals could discuss common problems facing their schools). We examined the intersection of pressure and support on principals and found that pressure without support may have negative effects on principal collective efficacy and reduce shared and instructional leadership behaviour. Further analysis of our data indicated that school leaders who reported being part of district leader networks – essentially professional communities for leaders – were more likely to be viewed as effective instructional leaders by their teachers (Lee, Louis, & Anderson, Citation2012). Although we were not able to determine what principals were talking about in their networks, it certainly appears that their discussions helped them to focus on the behaviors that teachers reported as most important for them: visiting their classrooms and asking interesting questions about instruction, raising issues of instruction in staff meetings and supporting instructional innovation (Demerath & Louis, in press). In addition, it was also apparent that principals who participated in PLCs with other principals were more likely to foster professional community within their school (Lee et al., Citation2012).

summarizes the local education factors that we suspect are most important for supporting and sustaining solid leadership behaviour at the school level. The figure re-emphasises that the local agency role in setting expectations for school improvement can have positive effects on teachers and students – if the expectations are coupled with creating a supportive and collaborative environment for school leader learning. The caveat is, of course, that this did not happen in most local education authorities nor was it experienced by most school leaders: Few US districts have a coherent professional development system for principals; most rely on episodic events; few principals have regular contact with a mentor or coach in the local education authority office; and only half of the school leaders in our survey agreed that the district leaders assist them to be better instructional leaders in their schools. In other words, lack of clarity about the role of local educational authorities continues to be common in the United States and, I suspect, in many other countries as well.

Discussion

The study on which this paper is based (which is currently the largest investigation of leadership for learning in the United States) obviously does not answer all of the questions that we might have about school leader effects. I would argue, instead, that its most important contribution may be to suggest questions that require further reflection and data. Furthermore, this short paper has not captured all of the findings that emerged from this very large study, but focused only on those that seem to have potential applicability in other countries, particularly the Nordic setting. Nevertheless, in spite of the limitations, there are some conclusions that can be considered.

First, the results suggest that the way forward in school effectiveness research should not necessarily be guided by an ever-sharper focus on teachers. Clearly teachers matter, but the quality of their work is shaped not only by what they know, how well they were trained and their subsequent experience, but also by the social conditions that they encounter in a school. These conditions are critically grounded in professional community, or the stimulating relationships that they have with other teachers that create effective individual and collective learning environments that support change. However, our study suggests that school leaders have a significant impact on whether supportive and challenging work environments exist for teachers. School leaders exert influence in the following ways:

Affect working relationships and, indirectly, student achievement (instructional leadership)

When influence is shared with teachers, foster stronger teacher working relationships (shared leadership)

Create a culture of support for teachers that is translated into support for student work (academic support)

In other words, school leaders shape the school culture in ways that make its members more productive as well as more satisfied.

Local education authorities have a more limited impact on teachers, except under unusual circumstances where there is extensive job-embedded professional development that is of high quality (Desimone, Citation2011). Although many US districts have leapt on the bandwagon of developing new roles for instructional coaches as a component of efforts to influence the quality of teaching, few studies have demonstrated an impact of education authority coaching programs on achievement, and there have been no cost–benefit analyses. In sum, at this time, local education authorities appear to have the most low-cost leverage to improve schools by improving school leadership. We do not have extensive data on how districts make a difference, but what comes through clearly is that creating settings in which ideas about leading improvement (particularly instructional improvement) are discussed is critical.

Returning to Sarason's (Citation1971, Citation1996) challenge, which focuses on changing power relationships in schools, this study only begins to scratch the surface. However, there are some clues. This summary suggests that the possibilities for school improvement are increased where the conscious barrier between teachers, between administrators and teachers, between schools and communities and between local educational authorities and schools are challenged. We do not know from this research whether integrative leadership that creates new working relationships will change the way in which teachers think about their ‘responsibility’ for managing a child's learning. However, our study indicates that teachers in a close professional community are more likely to teach in ways that give more power to students by incorporating constructivist strategies that are consistent with Scandinavian ideas of bildung as a core educational value. In other words, changing the culture of relationships among adults, both professionals and community members, can change the way in which teachers enact their responsibilities in classrooms.

In the context of the incessant policy drum beat of school accountability, our studies found that educational professionals at all levels could, under the right circumstances, continue to focus on longer-term organizational improvement, learning and continuous improvement rather than thinking only of the next round of state (or international) test results. Because the social composition of schools is changing rapidly in most countries, the fact that these results were found in poorer and more diverse as well as wealthier schools suggests room for optimism. We do not need to assume that increasing diversity will lead to fragmented schools and communities, although it will continue to pose challenges that caring leaders and professional, engaged teachers will need to meet with energy.

There is also room for hope that the working life of teachers can be improved, not with ‘bells and whistles’ such as new buildings or technology, but with changes in the social relationships that encourage each member of a school to be connected to others around the ‘knots’ of shared tasks and improved practice (Engeström, Citation2008). This finding is particularly critical for many countries, including some of the Nordic countries, where the incessant media focus on school failures has tended to undermine teacher morale. Although educational leaders cannot change the media, our data suggest that they can shape the important local stories that are told by teachers, parents and the local communities in ways that benefit teachers and students.

Finally, it is important to remember that, although this paper is a reflective interpretation of a US study with an effort to be sensitive to the situation of the Nordic countries, it raises questions for research rather than providing answers. What it does suggest is that, as a rich research tradition of studying leadership in Scandinavia develops, it should be fully engaged with the finding that leadership in schools belongs to many people and not just to a designated occupant of an administrative position.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karen Seashore Louis

Karen Seashore Louis is a Regents Professor and Robert H. Beck Chair at the University of Minnesota. Her current work focuses on school leadership, school culture, and knowledge use in schools.

Notes

1 Accumulated evidence from meta-analyses suggests that school effects as measured in multiple studies are less important than teacher effects (Scheerens, Citation2014).

2 I use the US term school district in this paper, but suggest that the US structure may generalise to other intermediate governance units, such as municipalities or kommuns, in other countries.

3 The term integrative leadership is also sometimes used when authors are developing a ‘grand conceptual framework’ to study individual leaders that combine models developed from different disciplines (Chemers, Citation1997). I am not using it in this way.

4 Our study began in the early years of the No Child Left Behind federal requirement that every state test students at multiple grade levels every year. Our student achievement data in the study were derived from the mandated state tests. This is, of course, a significant limitation since the quality and comparability of the tests is highly variable. For a discussion of the methods of managing this unwieldy set of data, see Louis et al. (Citation2010).

5 This observation also draws on work on leadership development that is based on other public sectors (Parks, Citation2005).

6 These data were extracted using the OECD interactive database at http://gpseducation.oecd.org/IndicatorExplorer

† Although I am responsible for the interpretive content of this paper, both my thinking and some of the findings presented are the work of colleagues who participated with me in this research. Where findings are part of joint papers, I will reference them at the appropriate point.

References

- Berends M., Bodilly S., Kirby S.N. Looking back over a decade of whole-school reform: The experience of New American Schools. The Phi Delta Kappan. 2002; 84(2): 168–175.

- Chemers M. An integrative theory of leadership. 1997; Matwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Crosby B.C., Bryson J.M. Integrative leadership and the creation and maintenance of cross-sector collaborations. The Leadership Quarterly. 2010; 21(2): 211–230.

- Demerath P.W., Louis K.S, Waite D., Bogotch I. U.S. contexts of/for educational leadership. The international handbook of educational leadership. in press; New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Desimone L.M. A primer on effective professional development. The Phi Delta Kappan. 2011; 92(6): 68–71.

- DuFour R., Fullan M. Cultures built to last: Systemic PLCs at work. 2013; Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

- Engeström Y. From teams to knots: Activity-theoretical studies of collaboration and learning at work. 2008; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Felber-Smith A. Students as mediators of effective school-community relationships: An exploration of how educational professionals make sense of students’ many social worlds (PhD thesis). 2015; Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

- Felner R.D., Favazza A., Shim M., Brand S., Gu K., Noonan N. Whole school improvement and restructuring as prevention and promotion: Lessons from STEP and the project on high performance learning communities. Journal of School Psychology. 2001; 39(2): 177–202.

- Firestone W., Louis K.S, Murphy J., Louis K.S. Schools as cultures. Handbook of research on educational administration. 2000; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. (2nd ed., pp. 297–322).

- Gordon M.F. Bringing parent and community engagement back into the education reform spotlight: A comparative case study(PhD thesis). 2010; Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. Dissertation Abstracts International-A 71/04.

- Gordon M.F., Louis K.S. Linking parent and community involvement with student achievement: Comparing principal and teacher perceptions of stakeholder influence. American Journal of Education. 2009; 116(1): 1–31.

- Gordon M.F., Louis K.S, Leithwood K., Louis K.S. How to harness family and community energy. Linking leadership to student learning. 2011; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. 89–106.

- Hall R.H. Occupations and the social structure. 1975; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hofstede G. Culture and organizations: Software of the mind. 1991; London: McGraw Hill.

- Hofstede G. Cultures consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). 2001; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede G., Neuijen B., Ohayv D., Sanders G. Measuring organizational cultures: A qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1990; 35(3): 286–316.

- Honig M.I., Rainey L.R. How school districts can support deeper learning: The need for performance alignment. 2015; Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future. Students at the Center: Deeper Learning Research Series.

- Jack Lam Y.L. School organizational structures: Effects on teacher and student learning. Journal of Educational Administration. 2005; 43(4): 387–401.

- Johnson C.C., Kahle J.B., Fargo J.D. A study of the effect of sustained, whole-school professional development on student achievement in science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2007; 44(6): 775–786.

- Knudson J., Shambaugh L., O'Day J. Beyond the school: Exploring a systemic approach to school turnaround. Policy and practice brief. 2011; California Collaborative on District Reform. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research.

- Kruse S.D., Louis K.S., Bryk A, Louis K.S., Kruse S. An emerging framework for analyzing school-based professional community. Professionalism and community: Perspectives on reforming urban schools. 1995; Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. 23–42.

- Langer J.A. Excellence in English in middle and high school: How teachers’ professional lives support student achievement. American Educational Research Journal. 2000; 37(2): 397–439.

- Larson M.S. The rise of professionalism: A sociological analysis. 1978; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Lee M., Louis K.S. Defining and measuring a strong school culture linked to student learning. 2012; Vancouver, BC: Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association.

- Lee M., Louis K.S., Anderson S. Local education authorities and student learning: The effects of policies and practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2012; 23(2): 123–138.

- Leithwood K., Louis K.S. Linking leadership to student learning. 2011; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Leithwood K., Louis K.S., Anderson S., Wahlstrom K. Review of research: How leadership influence student learning. 2004; New York: Wallace Foundation.

- Lomos C., Hofman R., Bosker R. Validating the concept of professional community. 2011; New Orleans, LA: Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association.

- Lortie D. Schoolteacher: A sociological study. 2002; Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Louis K.S. Changing the culture of schools: Professional community, organizational learning, and trust. Journal of School Leadership. 2007; 16: 477–487.

- Louis K.S., Dretzke B., Wahlstrom K. How does leadership affect student achievement? Results from a national US survey. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2010; 21(3): 315–336.

- Louis K.S., Lee M. School cultures and contexts that foster teachers’ capacity for organizational learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. in press

- Louis K.S., Leithwood K, Leithwood K., Louis K.S. From organizational learning to professional learning communities. Organizational learning in schools. 1998; Lisse, NL: Swets and Zeitlinger. 275–285.

- Louis K.S., Leithwood K., Wahlstrom K., Anderson S.A., Michlin M. Learning from leadership: Investigating the links to improved student learning: Final report of research findings. 2010; New York: Wallace Foundation.

- Louis K.S., Marks H.M. Does professional community affect the classroom? Teachers’ work and student work in restructuring schools. American Journal of Education. 1998; 106(4): 532–575.

- Louis K.S., Marks H.M., Kruse S.D. Teachers’ professional community in restructuring schools. American Educational Research Journal. 1996; 33(4): 757–798.

- Louis K.S., Murphy J., Smylie M. Caring principals: An exploratory analysis. 2014; Washington, DC: Paper presented at the University Council for Educational Administration.

- Louis K.S., Robinson V.M.J. External mandates and instructional leadership: Principals as mediating agents. Journal of Educational Administration. 2012; 50(5): 629–665.

- Marks H.M., Louis K.S. Does teacher empowerment affect the classroom? The implications of teacher empowerment for instructional practice and student academic performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1997; 19(3): 245–275.

- Marsh J.A., Strunk K.O., Bush S. Portfolio district reform meets school turnaround: Early implementation findings from the Los Angeles Public School Choice Initiative. Journal of Educational Administration. 2013; 51(4): 498–527.

- Moos L., Huber S, Townsend T. School leadership, school effectiveness and school improvement: Democratic and integrative leadership. International handbook of school effectiveness and improvement. 2007; Berlin: Springer. 579–596.

- Morse R.S. Integrative public leadership: Catalyzing collaboration to create public value. The Leadership Quarterly. 2010; 21(2):231–245. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.004.

- Newmann F.M., Marks H.M., Gamoran A. Authentic pedagogy and student performance. American Journal of Education. 1996; 104(4): 280–312.

- Parks S.D. Leadership can be taught: A bold approach for a complex world. 2005; Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Reynolds D., Sammons P., De Fraine B., Van Damme J., Townsend T., Teddlie C., Stringfield S. Educational effectiveness research (EER): A state-of-the-art review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2014; 25(2): 197–230.

- Rosenholtz S.J. Teachers' workplace: The social organization of schools. 1991; New York: Teachers College Press.

- Sarason S. The culture of the school and the problem of change (1st ed.). 1971; Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Sarason S. The predictable failure of educational reform: Can we change course before it is too late?. 1990; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Sarason S. Revisiting “The culture of the school and the problem of change”. 1996; New York: Teachers College Press.

- Scheerens J. School, teaching, and system effectiveness: Some comments on three state-of-the-art reviews. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2014; 25(2): 282–290.

- Schön D. Educating the reflective practitioner. 1987; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Scribner J., Cockrell K.S., Cockrell D.H., Valentine J.W. Creating professional communities in schools through organizational learning: An evaluation of a school improvement process. Educational Administration Quarterly. 1999; 35(1): 130–160.

- Scribner J., Hager D., Warn T. The paradox of professional community: Tales from two high schools. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2002; 38(1): 45–76.

- Toole J., Louis K.S., Hargreaves A, Murphy J., Louis K.S. Rethinking school improvement. Handbook of research on educational administration. 1999; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. 251–276.

- Tucker P.D., Stronge J.H. Linking teacher evaluation and student learning. 2005; Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Wahlstrom K, Leithwood K., Louis K.S. An up-close view of instructional improvement. Linking leadership to student learning. 2011; San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. 68–86.

- Wahlstrom K., Louis K.S. How teachers experience principal leadership: The role of professional community, trust, efficacy and distributed responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2008; 44(4): 498–445.

- Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. 1998; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix 1

Additional description of sampling and data collection

The two surveys each contained items from established instruments as well as new items. All attitudinal variables were measured with six-point Likert scales. The instruments were field-tested with teachers and meetings with respondents led to subsequent changes in the wording of questions to improve clarity. The finalized instruments were mailed to individual schools and were typically completed by all teachers during a school staff meeting. Each survey was accompanied by a blank envelope that could be sealed to ensure confidentiality so that none of the principals had access to the teachers’ responses.

The method of survey administration, which involved filling out surveys during a faculty meeting, makes a completely accurate response rate difficult, largely because of incomplete staff lists at the building level. However, because of the method of administration, it was more typical to get a large bundle of surveys (presumably a high within-school response rate) or none at all. In addition, a few schools that participated in 2005–2006 dropped out for 2008 and were replaced. This organizational non-response accounts for the eventual inclusion of 157 rather than 180 schools in most of the analyses. Each of the participating case study districts and schools (18 districts and 36 schools) was visited three times over the course of the project.