Figures & data

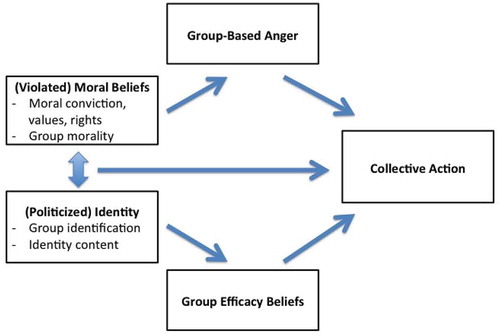

Figure 1. Extending the SIMCA further through a broader set of (violated) moral beliefs and (politicised) identity content.

Figure 2. Perceived right violation predicts movement identification. Reprinted with permission from Mazzoni et al., (Citation2015, Study 1) in Political Psychology 36, 315-330, © 2015 John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 3. Perceived right violation predicts movement identification. Reprinted from Mazzoni et al., (Citation2015, Study 2) in Political Psychology, 36, 315-330, © 2015 John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 4. The impact of personal/family and collective right violations on collective action intentions in the most and the least affected areas. Reprinted from Kutlaca et al. (Citation2017) with permission from Environment and Behavior, © 2017 SAGE Publications Inc.

Figure 5. The impact of perceived injustice (or affective motivation) on politicised identification among social science students when the value violation has been communicated as important to all Dutch people (Value-National Condition) or has not been communicated at all (Context-Only Condition). Reprinted from Kutlaca et al. (Citation2016) with permission from Social Psychology 2016; Vol. 47(1):15–28. © 2015 Hogrefe Publishing.

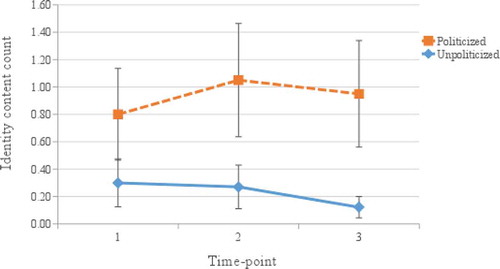

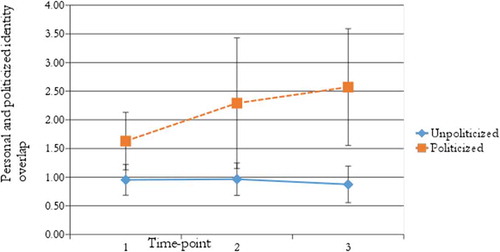

Figure 6. Mean absolute amount of personal and politicised identity content overlap for politicised and non-politicised participants, over time. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the 95% confidence interval around the estimate. Reprinted with permission from Turner-Zwinkels et al. (Citation2015), Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41, 433-445, © 2015 Sage Publications Inc.

Figure 7. Mean absolute amount of moral content recalled within the politicised identity for politicised and non-politicised participants. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the 95% confidence interval around the estimate.