Figures & data

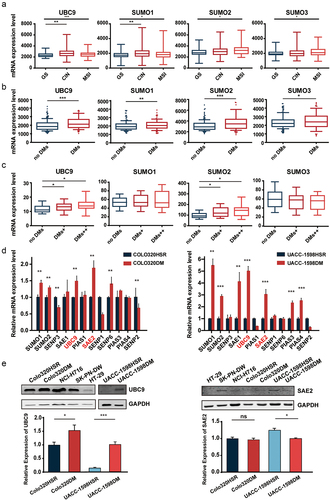

Figure 1. Higher expression of SUMOylation-related molecules are associated with increased genomic instability and double minute (DM) counts.

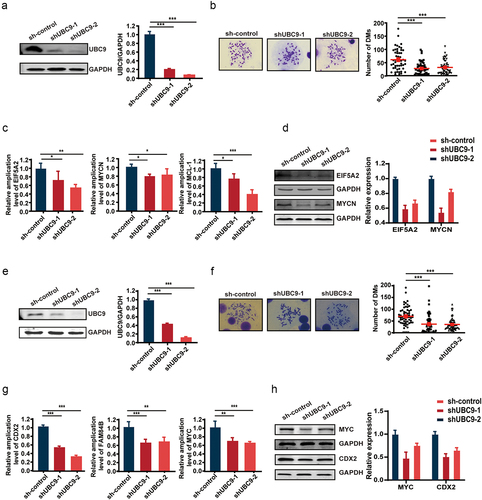

Figure 2. UBC9 knockdown is associated with lowered DMs and DM-carried gene expression.

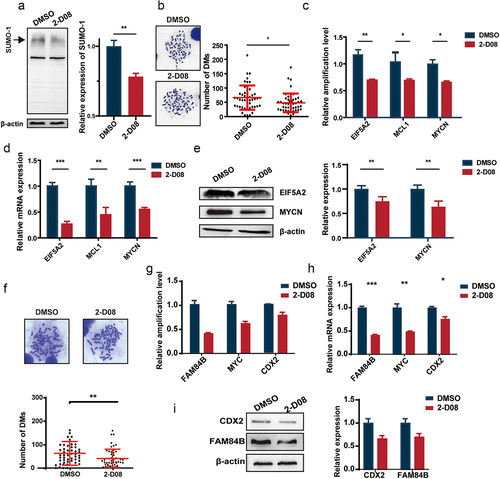

Figure 3. UBC9 inhibition by the 2-D08 inhibitor yields similar results as UBC9 knockdown, due to reduced SUMOylation.

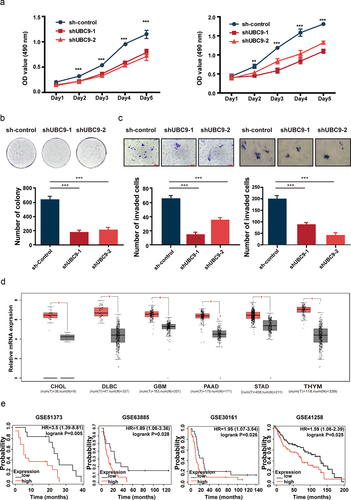

Figure 4. UBC9 knockdown reduces tumor malignancy and growth.

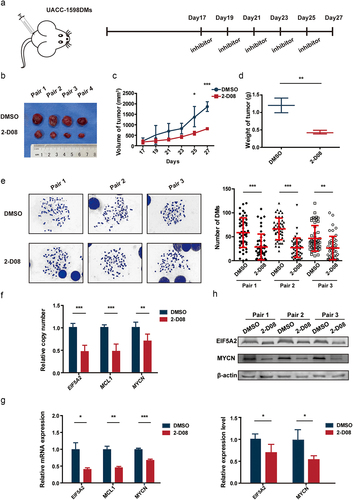

Figure 5. UBC9 inhibition in vivo decreases the rate of tumor growth, via eliminating DMs.

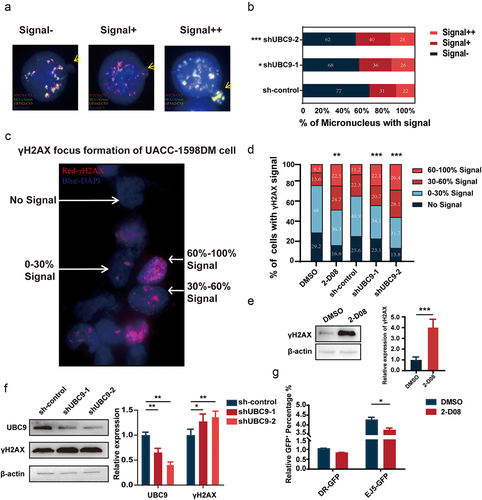

Figure 6. Lowered UBC9 activity is associated with increased micronucleus (MN) expulsion, DNA damage, and decreased DNA damage repair.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (11.5 MB)Data availability statement

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included within the article.