Figures & data

Box 1. Definitions of concepts.

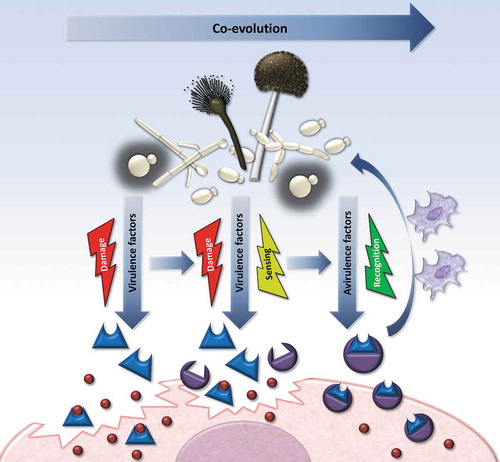

Figure 1. Illustration of virulence, antivirulence, and avirulence factors and their adaptive consequences within the host. Fungal factors expressed during host–pathogen interactions can lead to three different outcomes. From the pathogen’s perspective, a virulence factor (blue form) can be advantageous to overcome the host immune barrier, invade, or withstand stress conditions during infection. An antivirulence factor, in contrast, might be advantageous outside the host (green squares), but has a detrimental effect within the host, since it lowers the pathogen’s fitness, immune evasion ability or stress resistance. Lastly, a potential virulence factor can lose its function and become detrimental to the pathogen when the host develops specific receptors (purple form). If these recognize the factor or its action in the host, it can trigger an (immune) response that stops the progression of infection and turns the virulence factor into an avirulence factor.

Figure 2. Evolution of a virulence factor to an avirulence factor as a result of antagonistic co-evolution. A virulence factor confers the pathogen with an adaptive advantage within the host environment, which allows the infection to progress. However, frequent host–pathogen interactions act as a selection pressure on the host side to develop a specific defense response. As a result of this co-evolution the host can develop receptors that specifically recognize the pathogen’s virulence factor and trigger a specific (immune) response that counteracts and thereby abolishes the pathogen’s virulence. Note that new avirulence factor can still serve as a virulence factor in susceptible hosts that have not yet developed the specific response.