Figures & data

Table 1. Primers used in this study

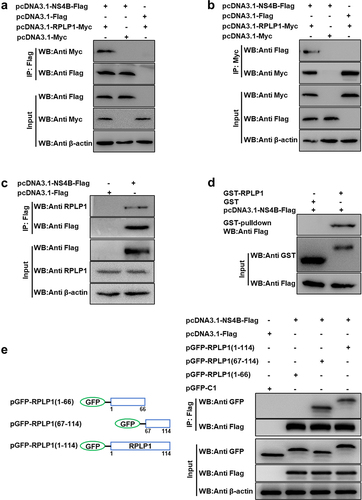

Figure 1. CSFV NS4B interacts with RPLP1.

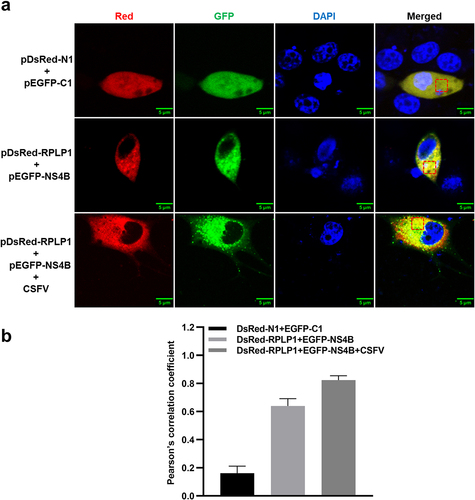

Figure 2. CSFV NS4B co-localizes with RPLP1.

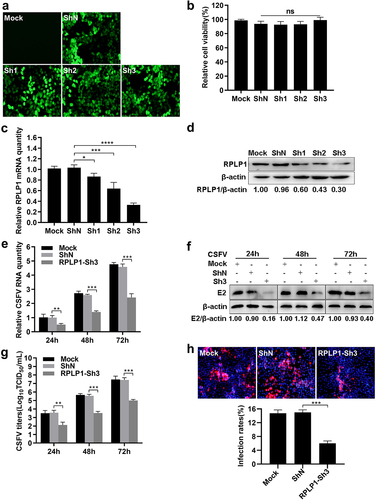

Figure 3. Knockdown of RPLP1 impairs CSFV infection.

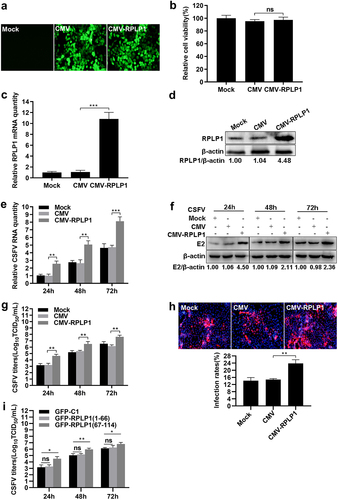

Figure 4. Overexpression of RPLP1 enhances CSFV proliferation.

Figure 5. CSFV infection upregulates the expression of RPLP1.

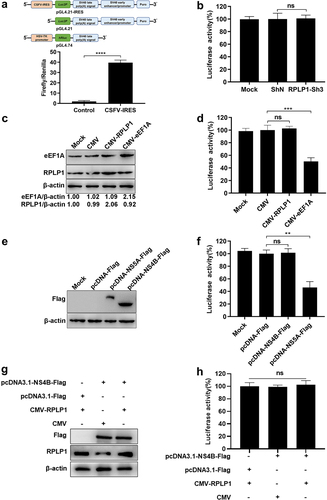

Figure 6. RPLP1 and NS4B take no significant effect on CSFV IRES activity.

Figure 7. RPLP1 is essential for translation of CSFV RNA.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, W. D., upon reasonable request.