Figures & data

Table 1. Sequences of specific primer pairs.

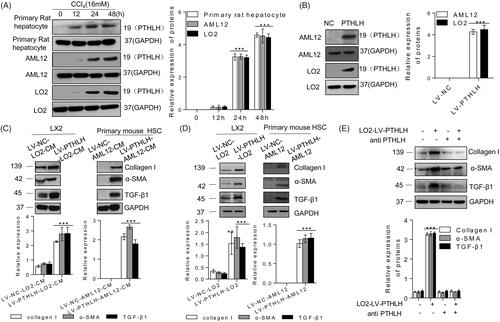

Figure 1. Accumulation of N-terminal PTHLH in supernatants of damaged hepatocytes and PTHLH treatment activated HSCs. (A, B) Primary rat hepatocytes and AML12 and LO2 cells were incubated with 16 mM CCl4 for the time period indicated or transduced with LV-NC or LV-PTHLH, and the protein expression of N-terminal PTHLH in the growth medium of hepatocytes was determined using the TCA method. Equal loading was confirmed by comparison with GAPDH levels. (C) LX2 cells were treated with LV-PTHLH-LO2 or LV-NC-LO2 cell conditioned medium (LV-PTHLH-LO2-CM and LV-NC-LO2-CM) and primary quiescent mouse HSCs were treated with LV-PTHLH-AML12 or LV-NC-AML12 cell conditioned medium (LV-PTHLH-AML12-CM and LV-NC-AML12-CM) for 24 h. Collagen I, TGF-β1 and α-SMA protein levels were analysed through Western blotting. (D) Western blotting to determine Collagen I, TGF-β1 and α-SMA protein expression in LX2 cells or primary quiescent mouse HSCs co-cultured with LV-NC or LV-PTHLH hepatocytes (LO2 or AML12) for 24 h. (E) LX2 cells were pretreated with neutralizing PTHLH antibody (5 µg/ml) for 2 h and then recombinant PTHLH(1–40) for 48 h. Western blots show the decrease in collagen I, TGF-β1 and α-SMA protein expression in PTHLH(1–40)-treated cells in response to the neutralizing PTHLH antibody (5 µg/ml). The relative protein levels were normalized to the GAPDH level. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < .05, **p < .01 and ***p < .001 versus controls.

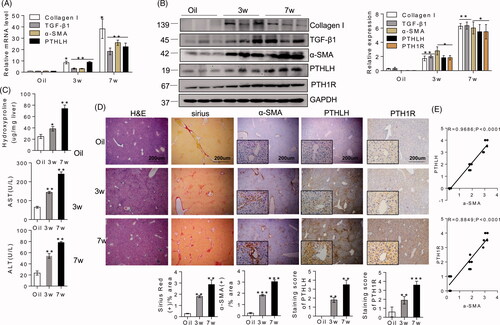

Figure 2. In CCl4-induced liver fibrosis mice, PTHLH was highly expressed in fibrotic livers. BALB/C mice were administered CCl4 (1 ml/kg, 1:4 mixture with mineral oil) twice/week for 3 and 7 weeks. (A, B) Quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblot analyses showed upregulation of PTHLH mRNA and protein in liver fibrosis models mice accompanied by increased TGF-β1, collagen I, and α-SMA increased. (C) Hepatic hydroxyproline content and serum ALT and AST levels. (D) Representative histology of livers from oil- and CCl4-treated mice at 3 and 7 weeks after H&E and Sirius Red staining. The Sirius Red staining was quantified by morphometric analysis. Immunohistochemical staining showing localization of α-SMA, PTH1R and PTHLH. The data for the accompanying graphs were generated from morphometric analysis. (E) Pearson correlation and linear analysis revealed that the α-SMA area was positively associated with PTHrP and PTH1R accumulation in liver sections from the fibrosis model. The relative mRNA levels are expressed as the fold induction over the control group after normalization to GAPDH, and the relative protein levels were also normalized to the GAPDH level. The data are the mean ± SD fold values over the control. *p < .05, **p < .01.

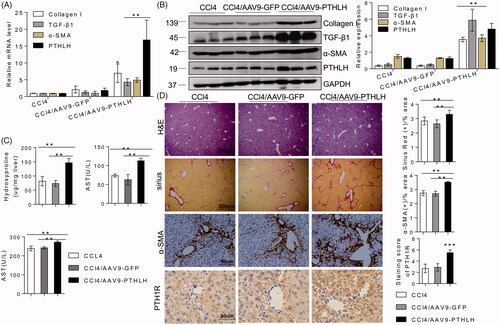

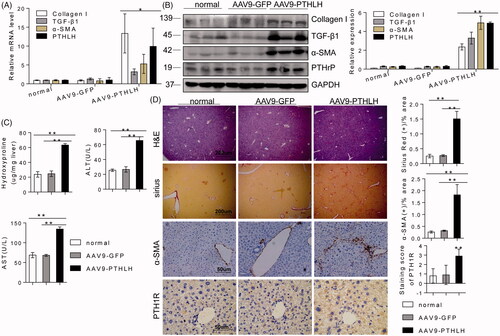

Figure 3. PTHLH accelerated murine liver fibrosis induced by CCl4. Liver fibrosis was induced by CCl4 administration (1 ml/kg, 1:4 mixture with mineral oil) twice/week for 5 weeks. Mice were treated with AAV9-GFP or AAV9-PTHLH through the tail vein, at doses of 1 × 1011 plaque-forming units in 0.1 ml of saline for 2 weeks before the first CCl4 injection. (A, B) The relative mRNA and protein levels of collagen I, TGF-β1, α-SMA and PTHLH were normalized to GAPDH levels. (C) The liver hydroxyproline levels and serum ALT and AST levels. (D) Representative microphotographs of H&E-stained or Sirius Red-stained paraffin-embedded sections of liver tissues and immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA and PTH1R; the Sirius Red, PTH1R and α-SMA staining scores were determined by morphometric analysis. The relative mRNA levels are expressed as the fold induction over the level in the vehicle-treated group after normalization to GAPDH, and the relative protein levels were also normalized to the GAPDH level. The data are the mean ± SD fold values over the control. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Figure 4. AAV9-PTHLH in the liver induced hepatic fibrosis. Mice were divided into three groups, normal mice not subjected to any treatment, and an AAV9-GFP and AAV9-PTHLH group that were treated with AAV9-GFP or AAV9-PTHLH, respectively, through the tail vein at doses of 1 × 1011 plaque-forming units in 0.1 ml of saline, and these mice hosted for 6 months. (A, B) Western blot analysis and quantitative RT-PCR showing the expression levels of collagen I, TGF-β1, α-SMA and PTHLH in response to AAV9-PTHLH injection into mice. (C) The liver hydroxyproline and serum ALT and AST levels in different group. (D) Representative microphotograph of H&E and Sirius Red-stained paraffin-embedded sections of liver tissues and immunohistochemistry staining of α-SMA and PTH1R. Sirius Red, PTH1R and α-SMA staining scores were determined by morphometric analysis. The relative mRNA levels are expressed as fold induction over the level in the normal group after normalization to GAPDH, and the relative protein levels were also normalized to the GAPDH level. The data are the mean ± SD fold values over the control. *p < .05, **p < .01.

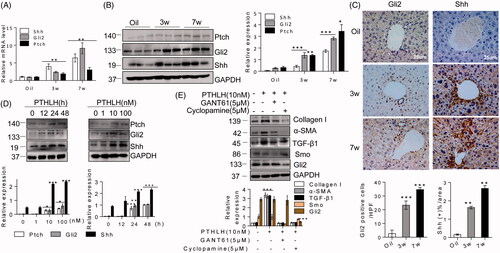

Figure 5. PTHLH triggered HSC activation and ECM production through the Hh pathway. (A, B) Western blotting and quantitative RT-PCR analyses showing the expression levels of Shh, Gli2 and Ptch in liver fibrosis model mice (3 and 7 weeks). (C) Photomicrographs of immunohistochemical staining for Gli2 and Shh at 3 weeks or 7 weeks showing Gli2 and Shh accumulation in fibrotic septa of fibrotic livers from mice subjected to control treatment or the CCl4 treatment (to induce liver fibrosis). Shh and Gli2 staining scores were obtained through morphometric analysis. (D) LX2 cells were treated with various concentrations of PTHLH(1–40) for 48 h or 10 nM PTHLH(1–40) for various time periods. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression levels of Ptch, Gli2 and Shh. (E) LX2 cells were pretreated with the SMO inhibitor of cyclopamine (5 µM) and GLI inhibitor GANT61 (5 µM) before exposure to 10 nM PTHLH(1–40) for 48 h. Collagen I, TGF-β1, α-SMA, Smo and Gli2 expression levels were measured through Western blot analysis. The relative mRNA levels are expressed as fold induction over the level in the vehicle-treated group after normalization to GAPDH, and the relative protein levels were also normalized to the GAPDH level. The data are the mean ± SD fold values over the control. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 versus controls.

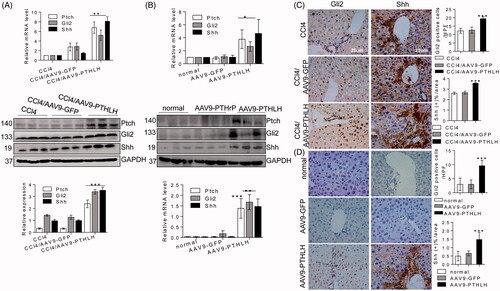

Figure 6. PTHLH treatment resulted in Shh and Gli2 accumulation in fibrotic livers. (A) Shh, Gli2 and Ptch mRNA and protein expression was observed in AAV9-GFP and AAV9-PTHLH mice after CCl4 injection for 5 weeks. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analyses were used to determine the mRNA and protein levels of Ptch, Gli2 and Shh in mice treated with AAV-GFP and AAV9-PTHLH and housed for 6 months. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for Shh and Gli2 and morphometric measurement of the Shh and Gli2 staining scores in AAV9-GFP and AAV9-PTHLH mice after CCl4 injection for 5 weeks. (D) Histomorphometric analysis to determine the percentage of Shh and Gli2 in mice treated with AAV-GFP and AAV9-PTHLH and housed for 6 months. The relative mRNA levels are expressed as fold induction over the level in the vehicle-treated group after normalization to GAPDH, and the relative protein levels were also normalized to the GAPDH level. The data are the mean ± SD fold values over the control. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001 versus controls.

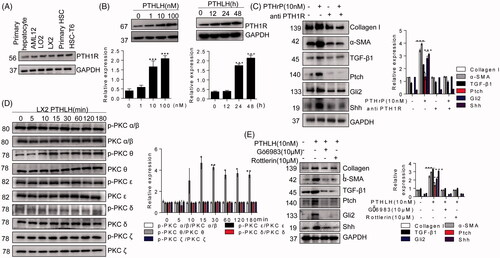

Figure 7. PTHLH (1–40) induced LX2 cell activation through PTH1R-PKC θ. (A) Western blotting analysis of protein harvested from different cells was conducted to confirm PTH1R expression in HSCs and hepatocytes. (B) LX2 cells were treated with various concentrations of PTHLH (1–40) for 48 h or 10 nM PTHLH (1–40) for various time periods. Western blotting was used to examine the expression levels of PTH1R. (C) Cells were pretreated with a neutralizing antibody targeting PTH1R (5 µg/ml) prior to treatment with PTHLH(1–40), and Western blotting was used to show collagen I, TGF-β1, α-SMA, Shh, Gli2 and Ptch protein expression. (D) In PTHLH(1–40) treated LX2 cells, the expression levels of phosphorylated and total PKC isoforms (δ, α, β, ε, ζ) were analysed by Western blotting. (E) LX2 cells were pretreated with the broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (10 µM) or the PKC-θ inhibitor rottlerin (10 µM) for 1 h and then incubated with 10 nM PTHLH(1–40) for 48 h. Collagen I, TGF-β1 and α-SMA expression was then measured by Western blotting. The relative protein levels were normalized to GAPDH, PKC δ, PKC α/β, PKC ε, t PKC θ, or PKC ζ levels as appropriate. The data are the mean ± SD fold values over the control. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001 versus controls.