Figures & data

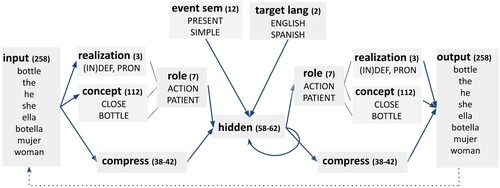

Figure 1. Bilingual Dual-path, the model used in our Spanish-English priming experiment. The model is an SRN-based model (the lower path, via the “compress” layers) that is augmented with a semantic stream (upper path) that contains information about concepts, thematic roles, event semantics, and the target language. The number of units per layer for the model used in Experiment 1 is shown in parentheses. The numbers of units for the hidden and compress layers vary across simulations.

Table 1. Sentence types in the artificial language input for the Spanish-English model.

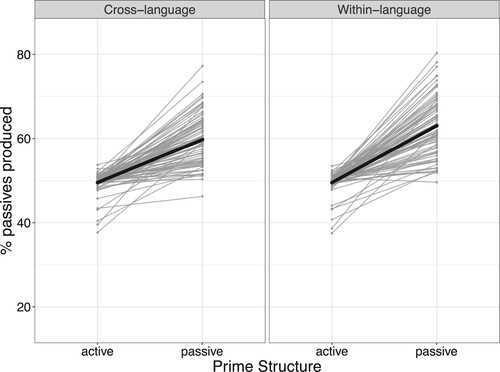

Figure 2. Percentage of responses in Experiment 1 (Spanish-English) that had a passive structure after either an active prime or a passive prime, for cross-language trials (on the left) or within-language trials (on the right). The thick black lines visualise the priming effect across all analysed trials by connecting the percentage of passive responses after active primes to the percentage of passive responses after passive primes. The thin grey lines show the same for each individual simulated participant.

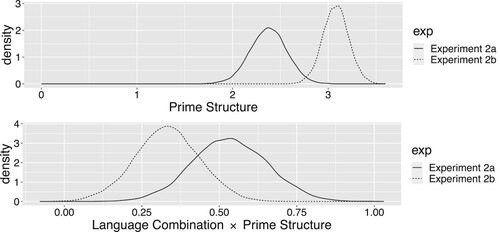

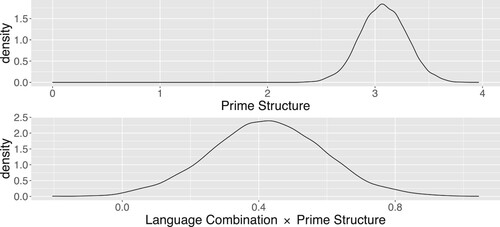

Figure 3. Posterior distributions of the estimate for the Prime Structure predictor (top) and of the estimate for the interaction between Language Combination and Prime Structure (bottom) in Experiment 1 (Spanish-English).

Table 2. Summary of the fixed effects in the Bayesian logistic mixed-effects model () for Experiment 1.

Table 3. Sentence types in the artificial language input for the Dutch-English models.

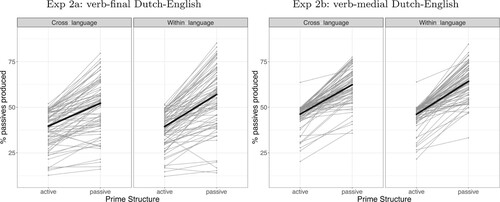

Figure 4. Percentage of responses in Experiment 2a (verb-final Dutch-English, left panel) and Experiment 2b (verb-medial Dutch-English, right panel) that had a passive structure after either an active or a passive prime, split by within- or cross-language trials. The thick black lines visualises the priming effect across all analysed trials by connecting the percentage of passives responses after active primes to the percentage of passive responses after passive primes. The thin grey lines show the same for each individual simulated participant.

Table 4. Summary of the fixed effects in the Bayesian logistic mixed-effects model () for Experiment 2a (verb-final Dutch-English).

Table 5. Summary of the fixed effects in the Bayesian logistic mixed-effects model () for Experiment 2b (verb-medial Dutch-English).

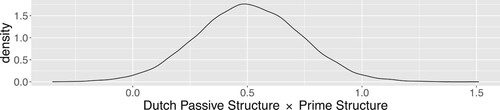

Table 6. Summary of the fixed effects in the Bayesian logistic mixed-effects model () for the combined analysis of the cross-language trials from Experiment 2a and 2b (verb-final and verb-medial Dutch-English).