Figures & data

Table 1. Summary of participant demographics.

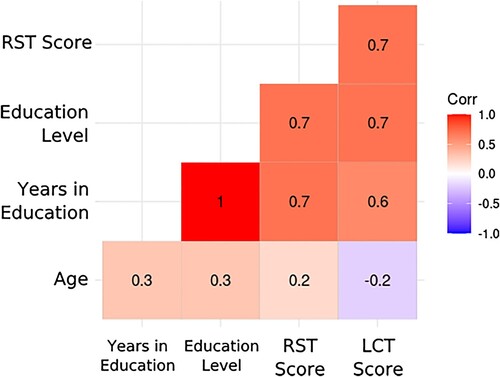

Figure 1. Covariance Matrix of predictors. Note that Years in Education and Education Level were not included in final models due to insignificant predictive power in every model.

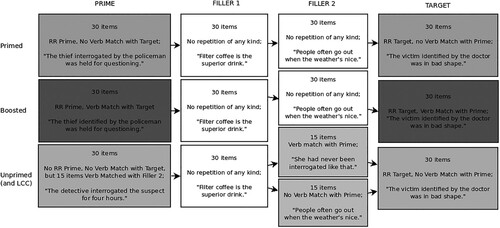

Figure 2. Schematic overview of experimental conditions. Each column denotes one sentence presented in sequence, such that all Primes and Targets were separated by two grammatically unrelated Fillers. Primed and Boosted Primes and Targets were both reduced relatives, while Prime sentences in Unprimed trials were syntactically unrelated to Targets. Verbs only matched between Primes and Targets in the Boosted condition. The LCC did not affect the verb matching of Prime and Target, but only manipulated lexical overlap between Prime and Filler 2.

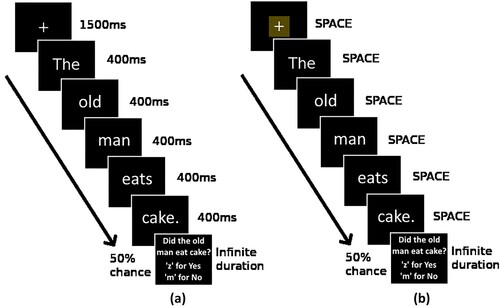

Figure 3. (a) displays externally-paced trials while (b) shows self-paced trials. Presentation of comprehension questions was fully randomised and did not depend on the presentation of a question in the previous sentence. Questions appeared after Primes, both Fillers, and Targets.

Table 2. Linear mixed model summary for the target (By) ROI.

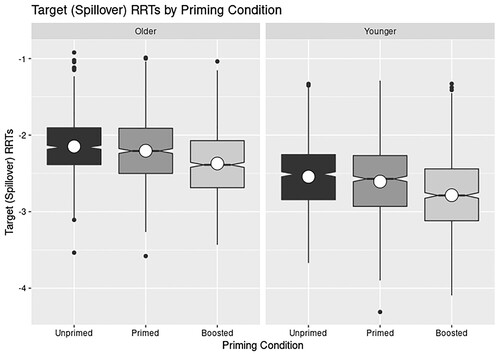

Figure 4. By-group overview of Priming Condition residualised reading times. Central dots indicate means for that condition. A clear stepwise facilitation effect can be seen in the plot, where primed trials were read faster than unprimed trials, and boosted trials faster than primed trials. Although reading times were universally slower in older compared to younger readers, age group did not affect reading times by condition.

Table 3. Linear mixed model summary for the target (Spillover) ROI.

Table 4. Linear mixed model summary for the LCC (Verb) ROI (RMarginal = .098; R

Conditional = .447).“Trial” denotes the numeric value of trial numbers in presentation order. Reference level for Repetition was Unrepeated. Significant values are represented in bold.

Table 5. Linear mixed model summary for the LCC (Spillover) ROI (RMarginal = .129; R

Conditional = .469). “Trial” denotes the numeric value of trial numbers in presentation order. Reference level for Repetition was Unrepeated. Significant values are represented in bold.