Figures & data

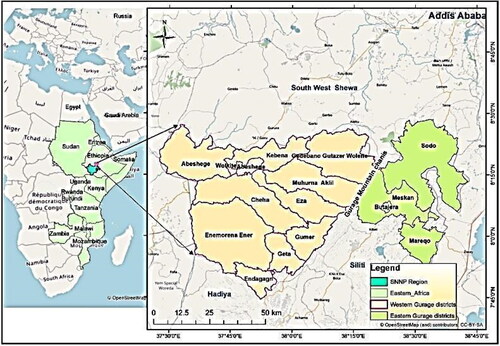

Figure 1. Map of the Sebat Bête Gurage area (Source: After Sahle & Saito, Citation2021b).

Figure 2. Jefore as green grass covered local road network and public space (Motta and Desene villages) left to right (Photo taken by corresponding author, August and September 2020).

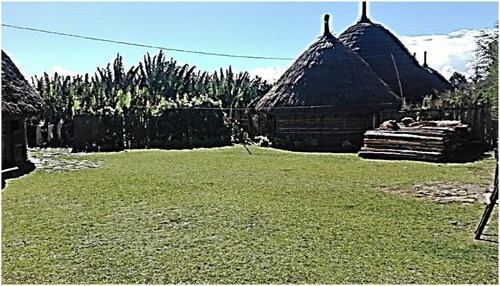

Figure 3. Sereges as village common or pasture in Weyeradeban village (Photo taken by corresponding author, September 2020).

Figure 4. Debirs as community forest in Kotir village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, January 2020).

Figure 5. Guye a traditional dwelling units of the Gurage in Denber village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, October 2020).

Figure 6. Wereje: a private open space as socio-economic space in Denber village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, October 2020).

Figure 7. Jefore as children playground and engagement place in Desene village left to right (Photo taken by the corresponding author, September and January 2020).

Figure 8. Jefore as youth engagements or sport place in Gech village (Photo taken by the corresponding author, December 2020).

Figure 9. Elders’ engagement in Yejoka (customary law tradition simulation at Mehuer Eyesus Jefore (public space) during World Tourism Day (Photo taken by the corresponding author, September 2016).

Figure 10. Dwelling qualities of craft verses peasant communities including spacing left to right in Zegba-Boto and Weyeradeban villages (Photo taken by the corresponding author, March 2019).

Figure 11. Features degraded Jefore road network and ecosystem services for landscape intrusions in Quqe village (Photos taken by the corresponding author, March 2019).

Figure 12. Degrading of sacred forests with competing religious values in Yesewa (shift to Orthodox Christian tradition) and Wegepecha (burning of sacred temple) left to right (Photos taken by the corresponding author, December 2020).