Figures & data

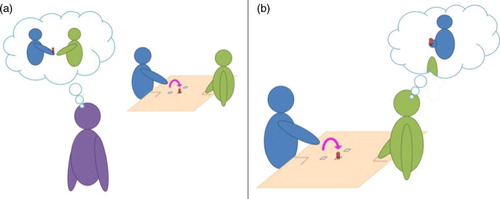

Fig. 1 Representation of the actions’ sequence in the study of Quesque et al. (Citation2013). The sequence always started with the wooden dowel placed on a nearby location and with the participant (in blue) and the partner (in green) pinching their index finger and thumb together on their respective starting positions (a). The Preparatory Action (b) consisted of displacing the wooden dowel from the nearby to the central location and was always performed by the participant, with no temporal constraint. The Main Action (c) consisted of displacing the wooden dowel from the central to the lateral location and could be performed either by the participant or by her partner, under strict temporal constraint. Finally, the Repositioning Action (d) was always performed by the participant and consisted of displacing the wooden dowel from the lateral to the nearby location, making the setup ready for the next trial.

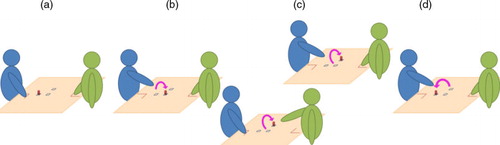

Fig. 2 Illustrations of (a) the ‘third-person’ and (b) the ‘second-person’ perspective. Classical experimental paradigms built to investigate humans’ mind-reading abilities use a third-person perspective (through photos, videos, or point-light display presentation of an actor). If participants are able to correctly categorise the stimuli above the level of chance, nothing is said about their understanding of the underlying intention of the actor. Switching from a ‘third person’ to a ‘second person’ perspective would allow distinguishing between categorisation and mind-reading abilities. If social intentions can actually be grasped through the observation of movement kinematics in a cooperative task, participants’ behaviours should be influenced (facilitation or interference effect) in consequence.