?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Price discounting strategies for suboptimal food perform an essential part in reducing food waste. This study provides new information empirically estimating discounts for levels of apple injury and deformity consistent with United States Department of Agriculture definitions using a Discrete Choice Experiment with Californian consumers. Latent Class Modelling identifies consumer segments with differing preferences for injury and deformity, alongside social responsibility and environmental claims. While discounts range substantially across segments, levels of deformity negatively influence choices more than equivalent levels of injury. Required discounts can be reduced by the presence of beneficial credence attributes, particularly an organic claim. We find a segment of respondents indifferent to suboptimal characteristics and requiring no discount to select suboptimal apples. These consumers have stronger preferences for environmental and social attributes, are more likely to be female, more educated, younger and concerned about genetic engineering. Preferences for social responsibility claims vary over the targeted beneficiaries, with programmes focused on workers preferred more overall. Willingness-to-pay for greenhouse gas reductions are relatively diminutive; however, 83% of the respondents support at least moderate reductions. This study contributes to understanding behaviours towards suboptimal food and is beneficial to forming food waste reduction strategies by identifying discount levels across consumer types.

I. Introduction

Food waste is a significant public issue with the economic cost valued at approximately US$990 billion globally (FAO Citation2019). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSG) call for ‘halving per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels’ by 2030 (UN Citation2015). Fruit and vegetable supply chains create relatively large volumes of waste with high environmental load that is predominantly created prior to reaching consumers resultant from overproduction and enforcement of cosmetic standards by retailers (Plazzotta, Manzocco, and Nicoli Citation2017).

Suboptimal apples are able to be retailed (USDA Citation2019), however consumer preferences over appearance play a crucial role in retailers marketing strategies. Visually suboptimal characteristics lower purchase intentions (Jaeger et al. Citation2018a; Symmank, Zahn, and Rohm Citation2018) and perceived product value (Kyutoku et al. Citation2018) are associated with quality concerns (Hartmann, Jahnke, and Hamm Citation2021) and negative hedonic expectations of consumers, which increase with the seriousness of the external imperfection (Jaeger et al. Citation2018b). While targeted public policy is generally lacking (Ryen and Babbitt Citation2022) food retailers are capable of influencing awareness and experiences of suboptimal food (Aschemann-Witzel Citation2018).

With consumers indicating that price-reductions are required to purchase suboptimal food (de Hooge et al. Citation2017; Helmert et al. Citation2017), provision of discounts can be an important measure to decrease and avoid food waste (Schanes, Dobernig, and Gozet Citation2018). Price reduction strategies in retail settings have been demonstrated to be successful strategies to encourage consumers to select suboptimal products (Aschemann-Witzela, Giménezb, and Ares Citation2018) with the marketing potential depending on the price setting for such products (de Hooge, van Dulm, and van Trijp Citation2018). While discount levels depend on the specific product and/or flaw (Hartmann, Jahnke, and Hamm Citation2021), the level of price reduction required to induce purchase is an under-researched area (Kulikovskaja and Aschemann-Witzel Citation2017) with a dearth of empirical research that goes beyond descriptive indications (Roodhuyzen et al. Citation2017) reflecting the scarcity of empirical research on suboptimal fruit (Louis and Lombart Citation2018). The central objective of this article is to expand understanding of the role of discounts by providing empirical insights on consumer preferences for apples with suboptimal characteristics and quantitative estimates of discounts associated with differing suboptimal characteristics in the presence of beneficial credence attributes.

Social and environmental beliefs can play an important role in generation of food waste (Di Talia, Simeone, and Scarpato Citation2019) with consumers who are more committed to environmental sustainability exhibiting stronger preferences for suboptimal fruits (de Hooge et al. Citation2017; Loebnitz and Grunert Citation2015) and consumers of suboptimal food generally regarded as environmentally concerned by others (Aschemann-Witzel et al. Citation2020). Marketing of suboptimal fruit can therefore be more successfully targeted at consumers with environmental and socially responsible values (Aschemann-Witzel et al. Citation2019) that is backed by inclusion of sustainability aligning product attributes and strengthened with price discounts (van Giesena and de Hooge Citation2019). Building on this literature, a main objective of this study is to analyse the effect of differentiated social responsibility attributes on apple choices that target support to workers, growers or local communities, as well as an environmental attribute focused on greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions in production.

The objectives of the study are accomplished by analysing models of consumer apple choice data collected using a Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE) of Californian apple consumers. The DCE includes moderate and significant levels of apple injury and deformity presented pictorially consistent with United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) standards alongside credence claims of organic production, reduction in GHG emissions and social responsibility actions focused on workers, growers or communities. We apply a two-stage approach to analyse apple choice observations by first applying a Mixed Logit model in wtp-space (MXL-WTP) used to test for the presence of attribute preference heterogeneity, and second a Latent Class Model (LCM) approach used to identify and describe consumer segment types with distinct preferences and characteristics. We select apples for fresh consumption as the case study fruit as the most consumed fruit in the United States and as being susceptible to cosmetic injury and deformity during growth (Stewart and Globig Citation2011). Apples are also one of the country’s most valuable fruit crops with utilized apple production totalling 9.6 bn lb valued at $3.03b in 2021 (USDA NASS Citation2021) and 67% of apples grown used for fresh consumption (USAA, Citation2022). Estimates of loss or wasted apples include 9% fresh apples lost at retail and 20% lost at the consumer level in the United States (Buzby et al. Citation2011). There are many diseases that can impact the cosmetic appearance of apples with some of the most common causing lesions and rust to appear on the skin and result in misshapen fruit (Stewart and Globig Citation2011). Injuries can also occur during harvest including from compression, and postharvest including from impact forces of mechanical processes in packinghouses (Bender, Muller, and Bender Citation2018).

Previous literature examining consumer preferences for apple attributes has applied Stated Preference methods including DCE (Kaye-Blake, Bicknell, and Saunders Citation2005), Contingent Valuation (McCluskey et al. Citation2007) and Conjoint Analysis (McCluskey et al. Citation2007). However, examination of cosmetic, environmental and social responsibility attributes is scant with consideration of preferences for organic production forming the focus in most studies (Wang, Sun, and Parsons Citation2009; Cerda et al. Citation2012; Moser and Raffaelli Citation2012; Sackett, Shupp, and Tonsor Citation2012; Denver and Jensen Citation2014; Bytyqi et al. Citation2015; Ceschi, Canavari, and Castellini Citation2018). Preferences for the origin of where apples are grown have also been frequently analysed (Bytyqi et al. Citation2015; McCluskey et al. Citation2007; Wang, Sun, and Parsons Citation2009; Moser and Raffaelli Citation2012; Skreli and Imami Citation2012; Novotorova and Mazzocco Citation2008). However, scant literature has empirically estimated consumer preferences and associated willingness-to-pay (WTP) for environmental attributes. Sackett, Shupp, and Tonsor (Citation2012) apply a DCE to apple consumers in the United States estimating WTP for ‘sustainable’ production, and several studies have applied DCE to apple and fruit consumers estimating WTP for GHG reductions (Akaichi et al. Citation2016; Moser and Raffaelli Citation2012; Aoki and Akai Citation2013; Tait, Saunders, and Guenther Citation2015). The literature empirically estimating WTP for suboptimal characteristics of fruit is particularly nascent and scant, and where available is of a general framing that lacks specificity to regulated cosmetic standards. Available examples are WTP estimates for good versus poor appearance (Moser and Raffaeli Citation2012) and perfect versus minor blemish in apples (de Hooge et al. Citation2017) and flawless versus flawed appearance in citrus fruit (Huang et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, relative to other credence attributes, preferences for social responsibility have been examined in only a limited number of studies and their consideration in consumers fruit choices is under researched (Miller et al. Citation2017) with meagre application within apple consumption and generalized fruit contexts (Miller et al. Citation2017), strawberries (Howard and Allen Citation2008) and bananas where Fair Trade certification is present in-market (Rousu and Corrigan Citation2008; Mahé Citation2010; Akaichi et al. Citation2016). The central contribution of this study is focused on addressing these knowledge gaps in the literature on consumer behaviours towards suboptimal food by providing new information of empirically estimated discounts for levels of apple injury and deformity and tradeoffs with beneficial credence attributes. Findings will be of particular use to industry stakeholders in forming supply chain and retail strategies aimed at reducing food waste by providing information on discount levels across different consumer types.

II. Materials and methods

Discrete choice experiment

Discrete Choice Experiments use surveys to value consumer preferences and are widely used in estimating WTP for food attributes. They are a valuable method for assessing consumer preferences for new attributes, and those that are not measurable in market prices, including the attributes examined here. This approach aims to simulate an apple choice context where respondents select their preferred apple from a set of alternatives that are differentiated by their attributes. In the current design, apple alternatives are characterized by changes in appearance, production systems and price.

Each apple within a choice set of alternative apples is described by attributes that differ in their levels, both across the alternatives and across choice sets. This concept is based on the characteristic theory of value (Lancaster Citation1966) positing that these attributes, when combined, provide consumers a level of utility. It is assumed that the apple alternative chosen is the one that maximizes an individual’s utility providing the behavioural rule underlying choice analysis:

where apple consumer n selects apple alternative j if this gives greater utility than alternative i. A theoretical cornerstone of this framework is Random Utility Theory (RUT) (McFadden Citation1974, Citation1986), dating back to early research on choice making (e.g. Thurstone Citation1927) and related probability estimation. This theory postulates that utility can be decomposed into systematic (explainable or observed) utility V and a stochastic (unobserved) utility ε (Lancsar and Savage Citation2004).

where j belongs to a set of J alternatives. The implication of this decomposition is that unobserved sources of utility can be treated as random, while the observed component is characterized by information describing apple attributes being examined as a linear function with their preference weights (coefficient estimates).

With K attributes in vector x for choice set s, estimated β parameters describe the effect on utility of a change in the level of each attribute. In the application here, this change is specified as linear for changes in the price of apples in each alternative, and as nonlinear for all other attributes by specifying attribute levels coded as dummy variables. It follows that the probability of individual n selecting apple alternative j is given by

Assuming that the error terms are drawn from a Gumbel distribution results in the multinomial logit model (MNL) (McFadden Citation1974) whose parameters can be retrieved using Maximum Likelihood estimation:

Within this framework we apply two econometric approaches to statistically analyse respondent’s apple choices. The first is an MXL-WTP (Train and Weeks Citation2005; Scarpa, Thiene, and Train Citation2008) to identify the significance of heterogeneity in respondents attribute preferences. The second analytical approach used is an LCM (Heckman and Singer Citation1984; Wedel and Kamakura Citation2000) used to parameterize preference heterogeneity within the sample and to identify associated characteristics of class profiles.

Preference heterogeneity is introduced into apple consumer choice probabilities (5) using an MXL-WTP model formulating the coefficient vector as individually specific and assumed distributed continuously as

) where

represents the parameters of the distribution. In this application we specify all non-price attribute parameters to randomly vary according to a normal distribution across respondents but remain constant across choices for the same respondent (Revelt and Train Citation1998). And

is assumed to be an independently and identically distributed type I extreme value distributed error. Under the MXL-WTP model, the utility expression is separable in price

and non-price attributes

.

To retrieve estimates of attribute WTP directly as coefficient estimates, this is re-formulated as

This model has no closed-form expression and so choice probabilities were estimated using simulated Maximum Likelihood using 1,000 Halton draws. This model estimates an SD for the randomly distributed portion of utility, and it is the statistical significance and magnitude of these estimates that identify the importance of preference heterogeneity that is to be further parameterized and described using the LCM. The LCM method describes the sample as comprised of a fixed and identifiable number of classes of individuals, where preferences vary between classes and are assumed homogenous within each class. Belonging to a specific consumer class is probabilistic and depends on both respondent choices and traits. The LCM method establishes the estimation of choice probability on the probability of choosing apple alternatives within each class, and the probability of an individual belonging to different classes. The conditional probability that individual n belonging to class q chooses the alternative j is

where describes the choice made by individual n is choice set s. The probability of an individual being a member of a particular class is

where contains variables describing an individual’s observable characteristics such as socioeconomic, apple purchase behaviours and environmental attitudes and beliefs. And

is a vector of coefficients to be estimated. Both modelling approaches are specified to account for the panel nature of the data and correlation between respondents’ choices (Revelt and Train Citation1998). We simulate unconditional estimates of WTP for each attribute as the ratio of the estimated LCM model parameters for each classes price variable and non-price attributes (Krinsky and Robb Citation1986; Cicia et al. Citation2013) and account for non-attendance behaviour (Kragt Citation2013) by recoding non-attended attributes to zero (Scarpa et al. Citation2009, Citation2013).

Choice experiment design

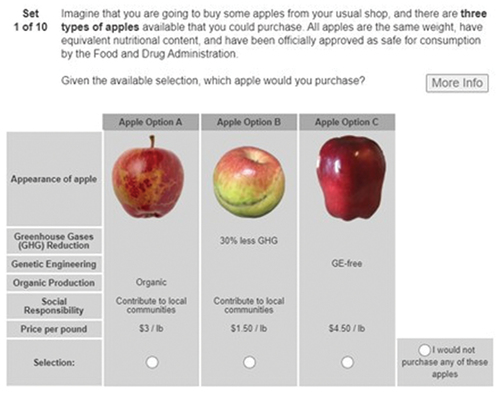

We design a DCE in which different apple options presented to respondents are described by suboptimality characteristics, environmental systems, social responsibility programmes and price (). Attribute selection was determined by literature review combined with a scoping survey that was designed to identify consumption behaviours and which attributes Californian apple consumers regarded as important. Scoping surveys are typically used to identify important concepts underlying a research idea and the main types of information available to inform development of more extensive research (Arksey and O’malley Citation2005). The scoping survey was conducted in December 2020 and consisted of 200 Californian residents who purchased apples at least monthly. The scoping survey did not include a DCE component, and the data collected does not form part of the dataset used for econometric modelling of preferences (). Changes in apple attributes are described using the labels in . Price levels were defined using in-market price scraping data and scoping survey usual prices. The primary attributes of focus for this study represent cosmetic standards in apple retailing with levels of appearance presented to respondents expressed using images, without written description. Pre-testing of the survey, including of pictorial representation of injury and deformity, established presentations consistent with USDA apple grade standards definitions (USDA Citation2019). A key distinction between grades is the extent of surface area that is permitted to be impacted by specific flaws. Our base comparison level for apple appearance is set as an ideal cosmetic standard consistent with the highest Grade ‘U.S. Extra Fancy’ that stipulates ‘fairly well formed, free from injury or injury, and has the specified amount of colour’. Moderate levels of deformity are consistent with USDA definition ‘fairly well formed’ meaning that the apple may be slightly abnormal in shape but not to an extent which detracts materially from its appearance. And significant deformity with USDA definition ‘seriously deformed’ meaning that the apple is misshapen to the extent that its appearance is seriously affected. Similarly, levels of moderate and significant injury are consistent with USDA descriptions which materially detract from the appearance of the apple. Apple injury presents as a defect which more than slightly detracts from the appearance of the apple (USDA Citation2019). We construct the moderate level of injury as a pronounced discoloured area of net-like russeting of up to 10% of the surface area. The significant level of injury as a scar with appreciable discoloration of the surface where the skin is healed, and the surface indentation exceeds one-eight inch (3.2 mm) in diameter. Pretesting of the pictorial presentation of appearance levels validated that the level design constructed for both deformity and injury attributes was consistent with apple consumers’ perceptions of moderate and significant deformity and injury.

Table 1. Apple attribute levels used in the DCE.

Table 2. Socio-demographics of survey respondents (n = 919).

As indicated in Section I, organic production has been identified as an important consideration in apple consumer preference research, and we include it here to provide a connection with that literature that aids in elucidating the relative importance for appearance attributes and other credence attributes considered. Similarly, consistent with the applied focus on preferences for organic apples is the associated role of genetic engineering (GE) in apple production and consumer preferences (Kaye-Blake, Bicknell, and Saunders Citation2005; Novotorova and Mazzocco Citation2008). In addition to the applied literature, the scoping survey of apple consumers indicated that this was an important consideration in apple purchase behaviour distinct from preferences for organic apples. Subsequently, we include GE-free as an apple attribute in the DCE design with the aim of identifying the relative importance of this production attribute separately from an organic standard that encompasses a broader range of practice requirements together with exclusion of GE technologies. Consistent with UNSG 13 directing action to combat climate change, we include a GHG reduction attribute to assess the inclusion on consumer apple choices. To identify plausible levels of GHG reductions that could realistically be achieved in apple production, we utilize the findings of a study of disease-resistant varieties that require less intensive spray regimes compared to conventional apple varieties (Harker et al. Citation2022). That study estimated that GHG reductions of 15% to 30% would result from lower pesticide use, we therefore adopt the end points of this range as our levels in the DCE. We include a social responsibility attribute as an under-researched credence attribute in consumer preference analysis generally and particularly in fruit products (Miller et al. Citation2017). The target beneficiary type of a social responsibility programme can affect consumer preferences when differentiated across human, animal, or environmental beneficiaries (Tully and Winer Citation2014). Our approach, novel to fruit choice context, is to define an attribute with three levels representing responsibility programmes differentiated by targeted beneficiaries across growers (Support growers), workers (Care for workers) and effects on local communities (Contribute to local community).

A DP-efficient fractional factorial experimental design was constructed using Ngene™ (ChoiceMetrics Citation2021) consisting of three apple options and an opt-out (‘I would not purchase any of these apples’) and blocked into three with each respondent facing 10 choice sets (). Initial design coefficients were updated with those from a model estimated on pilot survey data (n = 100) with the revised design used in the remaining sample. To allow for identification of any preference additionality for Organic relative to the GE-free standard, the design was restricted so that each of these attributes did not appear contemporaneously in any choice set alternatives. The resulting experimental design exhibits a D-error of 0.0283 and an S-estimate of 249. While our design has not been constructed specifically for S-efficiency, the S-estimate provides an indication of the lower bound on the necessary sample size in order to obtain significant parameter estimates (Bliemer and Rose Citation2005, Citation2009). A cheap-talk script was included to ameliorate hypothetical bias (Mahieu, Rierra, and Giergiczny Citation2012).

Cognitive interviews were employed to obtain feedback on draft questionnaires and pre-test the final survey version (Dillman, Smyth, and Christian Citation2014). Survey administration was directed to consumers with at least monthly purchase frequency with the sample of Californian apple consumers obtained from Dynata™ (www.dynata.com) and administered online in January 2021 using Qualtrics™ (www.qualtrics.com).

Sample statistics

The sampling process achieved 919 useable responses with each respondent completing 10 choice sets resulting in 9,190 observations for modelling. Looking at the socio-economic characteristics () the sample consisted of 41% males, with all respondents aged between 20 and 80 years, and just over half of the sample living in a suburban location. Almost 60% of the respondents live in households with children, and two-thirds have at least a university degree level of education. A summary of apple consumption behaviours included in shows that just over a quarter of the sample have previously bought apples with suboptimal characteristics, commonly marketed as ‘ugly’ fruit, over a third of respondents consume apples daily, and the average of prices usually paid is $2.8/lb. The survey solicited information regarding respondents’ attitude towards the importance of reducing environmental impacts of apple production, and the use of genetic engineering (GE) in apple production, using a five-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Similarly, we include attitudes towards cosmetic appearance using a five-point Likert-scale from very important to very unimportant. reports the percentage of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that reducing environmental impact was important (64%) and that GE poses significant risks (58%), and respondents who considered perfect appearance to be important or very important (50%).

III. Results and discussion

Estimating apple attribute willingness-to-pay

Statistical analysis was performed with NLogit6® (www.limdep.com). The MXL-WTP model choice probabilities are simulated using 1,000 Halton draws with all attribute parameters assumed to be distributed normal (). The negative and significant opt-out parameter estimate indicates that respondents generally preferred the apple choices presented; however, 14% of choices were for the opt-out alternative. Over a third of opt-out choices were made by 46 respondents who selected the opt-out in eight or more choice sets. These respondents stated that the main reason was affordability, an unwillingness to pay for product claims, or that the given products did not represent their preferences. Injury and deformity characteristics WTP are significant and negative, with deformity having the largest negative impact on apple choices at each comparative level with injury. Consistent with standard economic theory, we see that preferences are sensitive to scale, whereby WTP increases with provision of a good, in this case (negative) WTP increases with worsening injury or deformity. Also, those preferences exhibit diminishing returns to scale, whereby disutility of initial suboptimal levels from perfect to moderate injury or deformity is greater than the marginal increase in disutility from subsequent worsening injury and deformity (Mazur and Bennett Citation2009). We also see that organic production is the highest valued credence attribute ($1.13 ± 0.14). Importantly, this model identifies statistically significant preference heterogeneity as revealed in estimates of SDs across all apple attributes, with these being largest for injury and deformity characteristics. This finding of substantial heterogeneity in preferences motivates the application of an LCM approach to provide finer resolution on consumer behaviours within the sample.

Table 3. Mixed Logit model in WTP-space of apple choices.

Turning to the LCM analysis (), the number of classes is guided by statistical decision criteria and by the interpretability and simplicity of the model (Boxall and Adamowicz Citation2002). We use a combination of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the log-likelihood (LL) model performance statistics to inform the choice of the number of classes (Ruto, Garrod, and Scarpa Citation2008). Considering these measures indicates that a four-class model is superior compared to two-, three-and five-class models. Three classes are of similar size, and one is relatively smaller. The average class probabilities represent the likelihood that a randomly selected Californian apple purchaser belongs to that consumer group. The models explanatory power, as measured by the McFadden Pseudo-R2 can be considered as good (McFadden Citation1974; Hensher, Rose, and Greene Citation2015) and all price parameters are negative and statistically significant indicating consumers prefer lower priced apple alternatives. All classes opt-out choice parameters are also negative and significant indicating that each class of respondents gained more utility from selecting one of the apple alternatives presented rather than not.

Table 4. Latent Class Model of consumers apple choices.

Latent Class one is the smallest consumer class, comprising 17% of consumers. These consumers are primarily concerned with avoiding suboptimal cosmetic characteristics, with none of the credence attributes having a significant effect on their apple choices. Examining class membership variables indicates that members of this group are more likely to be relatively older, and less likely to think environmental impacts are important to consider in their purchase decision. Conversely, consumers in Class 2, comprising 27% of consumers, are primarily focused on social and environmental attributes in their apple choices. Importantly, these consumers are indifferent to changes in suboptimal characteristics when choosing between apple options. Members of this group are more likely to be younger, female and to believe that there are significant risks with the use of GE in apple growing. Class 3 consumers consider the broadest set of attributes in their apple choices of the four consumer classes identified with these consumers exhibiting significant preferences for all the attributes included in the DCE. Class four consumers have the highest WTP of the four segments for organic production, but they also have the strongest preferences for avoiding deformed or injured apples.

Analysis of willingness-to-pay heterogeneity

We simulate distributions of WTP for the LCM model and report the mean and 95% confidence intervals (Krinsky and Robb Citation1986) (). Preference ordering for discounts is consistent across the MXL-WTP estimates and the three LCM segments that require them. With the greatest discounts required for ‘Significant Deformity’, followed by ‘Significant Injury’. In Classes 3 and 4, required discounts for moderate deformity are greater than for moderate injury. Leaving aside for the moment the discount estimates for Class 2 which are by definition zero as they don’t require them, and Class 4 who are, in practical terms, adverse to suboptimal apples at any realistic price point. Then, for the remaining 55% of consumers, discount rates as a percentage of the average price used in the DCE ($3/lb) for Moderate Injury range between −14% (Class 3) and −23% (Class 1), for Significant Injury −21% (Class 3) and −49% (Class 1), and for Significant Deformity −37% (Class 3) and −60% (Class 1). These estimates when contrasted against the very limited comparative literature available, that use generalized suboptimal definitions, demonstrate that the research design used here has identified a larger range of preferences that is able to provide improved detailed insights. Moser and Raffaelli (Citation2012) estimate a 65% discount for ‘bad’ appearance relative to a ‘good’ apple, de Hooge et al. (Citation2017) a 67% discount estimated for a ‘minor blemish’ relative to ‘perfect’ apple appearance, and Huang et al. (Citation2021) a 53% discount for ‘flawed’ citrus relative to ‘flawless’.

Table 5. Consumer willingness-to-pay estimates from the Latent Class Model of consumers apple choices.

Our findings for organic production are consistent with previous literature recognizing this attribute as important to many apple consumers and our estimates of WTP, ranging from zero in Class 1, 17% (Class 3) to 88% (Class 2) and 104% (Class 4) are consistent with others estimates ranging from 11% (Ceschi, Canavari, and Castellini Citation2018), 22% (Arcadio et al., 2012), 26% (Denver and Jensen Citation2014), 41% (Moser and Raffaelli Citation2012), 59% in the USA (Sackett, Shupp, and Tonsor Citation2012) and 147% (Bytyqi et al. Citation2015). Our estimates of WTP for differentiated Social Responsibility claims differ significantly between classes of consumers, with zero WTP for any claims by members of Class 1 and 4, while Class 2 has the highest WTP across the sample (64% to 75%), and Class 3 having moderate levels of WTP (7% to 18%). Overall, claims centred on Care for Workers appear to be preferred marginally more over efforts targeted towards growers or communities. Our definitions differ from those examined in fruit preferences to date and so represent new information not previously available, however when compared to Fair-Trade standard context studies they are generally consistent with the range found, including, at the lower end, a 9% premium for ZFair Trade bananas in the USA (Rousu and Corrigan Citation2008) through to Miller et al. (Citation2017) who found a range of 34% (UK) to 60% (Japan) for improvement above minimum standards for fruit and vegetables. And towards the upper end, a 68% premium for Fair Trade strawberries in the USA (Howard and Allen Citation2008), and premiums for Fair Trade bananas in the Netherlands (69%) and France (108%) (Akaichi et al. Citation2016).

We find consumers’ relative WTP for reductions in GHG, while significant in three of the four consumer Classes, to sit moderately below the other credence attributes considered here. Members of Class 2 are WTP 37% for a 15% reduction, but only marginally more for twice the level of reduction (44%). While members of Class 3 are WTP 10% for a 15% reduction and appear to be unwilling to pay for greater reductions. Similarly, members of Class 4 are WTP for initial levels of reduction (37%) but not for further decreases. Although directly comparative literature is relatively scant, these estimates are consistent with those available including a 7% premium for mandarins with 10% GHG reduction in Japan (Aoki and Akai Citation2013), 10% more for bananas with 15% less GHG by Scottish consumers, and 14% more by French and Dutch (Akaichi et al. Citation2016), 16% premium for ‘low’ GHG apples in the USA (Moser and Raffaelli Citation2012), 23% for fruit with 10% GHG reduction (Tait, Saunders, and Guenther Citation2015).

IV. Conclusions

Several studies of consumer behaviour towards suboptimal fruit have demonstrated an opportunity for price discounting to stimulate consumption demand. However, there is scant literature that empirically estimates the levels of discounts required by consumers to offset suboptimal characteristics, or that identifies and describes differing consumer segments and their responses to these characteristics in fruit choices. To contribute to filling this gap, we conduct a study in California using a Discrete Choice Experiment of apple consumers to assess the tradeoffs that consumers make across suboptimal injury and deformity characteristics, and credence attributes of environmental and social responsibility claims.

Our results identified significant preference heterogeneity in the sample across four classes of consumers within a Latent Class Model framework. We find that over a quarter of consumers are indifferent to the presence of suboptimal characteristics in their apple choices and do not require a price discount to select such apples (Class 2). These consumers also exhibit stronger preferences for the social and environmental attributes considered, which is consistent with the general literature noting that consumers more committed to environmental sustainability are more likely to select suboptimal fruit. A further 28% of consumers require relatively modest levels of discount, particularly for moderate levels of injury and deformity (Class 3), and 28% require discounts that can be considered as unrealistic for producers and retailers to offer (Class 4). We also find that, overall, organic production is the most highly valued credence attribute considered, and that while GHG reductions are towards the lower end of WTP estimates, 83% of consumers are WTP for some GHG reduction in apple production. For many consumers, socially responsible and GE-free claims are valued significantly, with 55% of consumers having positive WTP for these claims. And that preferences for social responsibility claims vary over the targeted human beneficiaries, with overall results suggesting that programmes focused on workers generate greater value for consumers.

The findings of this study offer significant support for discount strategies to increase demand for suboptimal fruit and the opportunity to reduce cosmetically driven food waste, especially when beneficial environmental and social claims are also present. Discounts can play an important role in persuading consumers to initially try cosmetically suboptimal fruits and communication of the environmental and societal impacts of cosmetically driven food waste may be expected to further increase consumer demand. Extending the research applied here to non-hypothetical choice experiments, other fruits and countries, will aid in establishing the generalizability of results obtained here.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the New Zealand Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment: Our Land and Water National Science Challenge Integrating Value Chains Programme [CN17010465].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akaichi, F., S. de Grauw, P. Darmon, and C. Revoredo‐giha. 2016. “Does Fair Trade Compete with Carbon Footprint and Organic Attributes in the Eyes of Consumers? Results from a Pilot Study in Scotland, the Netherlands and France.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 29 (6): 969–984. doi:10.1007/s10806-016-9642-7.

- Aoki, K., and K. Akai. 2013. “Do Consumers Select Food Products Based on Carbon Dioxide Emissions?” In Advances in Production Management Systems: Competitive Manufacturing for Innovative Products and Services, edited by C. Emmanouilidis, M. Taisch, and D. Kiritsis, 345–352. International Federation for Information Processing Advances in Information and Communication Technology. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40361-3_44.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. 2018. “Consumer Perception and Preference for Suboptimal Food Under the Emerging Practice of Expiration Date-Based Pricing in Supermarkets.” Food Quality and Preference 63: 119–128. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.08.007.

- Aschemann-Witzela, J., A. Giménezb, and G. Ares. 2018. “Consumer In-Store Choice of Suboptimal Food to Avoid Food Waste: The Role of Food Category, Communication and Perception of Quality Dimensions.” Food Quality and Preference 68: 29–39. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.01.020.

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., T. Otterbring, I. E. de Hooge, A. Normann, H. Rohm, V. L. Almli, and M. Oostindjer. 2019. “The Who, Where and Why of Choosing Suboptimal Foods: Consequences for Tackling Food Waste in Store.” Journal of Cleaner Production 236: 117596. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.07.071.

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., T. Otterbring, I. E. de Hooge, A. Normann, H. Rohm, V. M. Almli, and M. Oostindjer. 2020. “Consumer Associations About Other Buyers of Suboptimal Food – and What It Means for Food Waste Avoidance Actions.” Food Quality and Preference 80: 103808. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103808.

- Bender, R. J., I. Muller, and S. D. S. Bender. 2018. “After Harvest, Mechanical Injuries on Apples.” Acta Horticulturae 1194 (1194): 793–798. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2018.1194.112.

- Bliemer, M. C. J., and J. M. Rose. 2005. Efficiency and Sample Size Requirements for Stated Choice Studies. Report ITLS-WP-05-08, Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/19535.

- Bliemer, M. C. J., and J. M. Rose. 2009. “Constructing Efficient Stated Choice Experimental Designs.” Transport Reviews 29 (5): 587–617. doi:10.1080/01441640902827623.

- Boxall, P. C., and W. L. Adamowicz. 2002. “Understanding Heterogeneous Preferences in Random Utility Models: A Latent Class Approach.” Environmental and Resource Economics 23 (4): 421–446. doi:10.1023/A:1021351721619.

- Buzby, J. C., J. Hyman, H. Stewart, and H. F. Wells. 2011. “The Value of Retail- and Consumer-Level Fruit and Vegetable Losses in the United States.” The Journal of Consumer Affairs 45 (3): 492–515. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2011.01214.x.

- Bytyqi, N., E. Skreli, A. Verçuni, D. Imami, and E. Zhllima. 2015. “Analysing Consumers’ Preferences for Apples in Pristina, Kosovo.” Die Bodenkultur: Journal Land Management Food Environmental 66: 1–2.

- Cerda, A. A., L. Y. García, S. Ortega-Farias, and A. M. Ubilla. 2012. “Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Organic Apples.” Ciencia e investigación agraria 39 (1): 47–59. doi:10.4067/S0718-16202012000100004.

- Ceschi, S., M. Canavari, and A. Castellini. 2018. “Consumer’s Preference and Willingness to Pay for Apple Attributes: A Choice Experiment in Large Retail Outlets in Bologna (Italy).” International Journal of Food and Agriculture Marketing 30 (4): 305–322. doi:10.1080/08974438.2017.1413614.

- ChoiceMetrics. 2021. Ngene 1.1.3 User Manual and Reference Guide. ChoiceMetrics Pty Ltd. Available at http://www.choice-metrics.com/documentation.html.

- Cicia, G., L. Cembalo, T. Del Giudice, and R. Scarpa. 2013. “Country-Of-Origin Effects on Russian Wine Consumers.” Journal of Food Products Marketing 19 (4): 247–260. doi:10.1080/10454446.2013.724369.

- de Hooge, I. E., M. Oostindjer, J. Aschemann-Witzel, A. Normann, S. M. Loose, and V. L. Almli. 2017. “This Apple is Too Ugly for Me! Consumer Preferences for Suboptimal Food Products in the Supermarket and at Home.” Food Quality and Preference 56: 80–92. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.09.012.

- de Hooge, I. E., E. van Dulm, and H. C. M. van Trijp. 2018. “Cosmetic Specifications in the Food Waste Issue: Supply Chain Considerations and Practices Concerning Suboptimal Food Products.” Journal of Cleaner Production 183 (10): 698–709. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.132.

- Denver, S., and J. D. Jensen. 2014. “Consumer Preferences for Organically and Locally Produced Apples.” Food Quality and Preference 31: 129–134. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.08.014.

- Dillman, D. A., J. D. Smyth, and L. M. Christian. 2014. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. -4th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- FAO, 2019. Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. SAVE FOOD: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. Key Facts on Food Loss and Waste You Should Know. Available here http://www.fao.org/save-food/resources/keyfindings.

- Harker, R., C. Roigard, D. Jin, G. Ryan, S. L. Chheang, D. Hedderley, A. Colonna, and P. Dalziel. 2022. Unlocking Export Prosperity: USA Sensory Study on the Value of Distinctive and Superior Eating Quality. A Plant & Food Research report prepared for: Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, Lincoln University, New Zealand.

- Hartmann, T., B. Jahnke, and U. Hamm. 2021. “Making Ugly Food Beautiful: Consumer Barriers to Purchase and Marketing Options for Suboptimal Food at Retail Level – a Systematic Review.” Food Quality and Preference 90: 104179. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104179.

- Heckman, J. J., and B. Singer. 1984. “Econometric Duration Analysis.” Journal of Econometrics 24 (1–2): 63–132. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(84)90075-7.

- Helmert, J. R., C. Symmank, S. Pannasch, and H. Rohm. 2017. “Have an Eye on the Buckled Cucumber: An Eye Tracking Study on Visually Suboptimal Foods.” Food Quality and Preference 60: 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.03.009.

- Hensher, D. A., J. M. Rose, and W. H. Greene. 2015. Applied Choice Analysis. second ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Howard, P., and P. Allen. 2008. “Consumer Willingness to Pay for Domestic ‘Fair Trade’: Evidence from the United States.” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 23 (03): 235–242. doi:10.1017/S1742170508002275.

- Huang, W., H. Kuo, S. Tung, and H. Chen. 2021. “Assessing Consumer Preferences for Suboptimal Food: Application of a Choice Experiment in Citrus Fruit Retail.” Foods 10: 15. 2021. doi:10.3390/foods10010015.

- Jaeger, S. R., L. Antúnez, G. Ares, M. Swaney-Stueve, D. Jin, and F. R. Harker. 2018a. “Quality Perceptions Regarding External Appearance of Apples: Insights from Experts and Consumers in Four Countries.” Postharvest Biology and Technology 146: 99–107. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2018.08.014.

- Jaeger, S. R., L. Machín, J. Aschemann-Witzel, L. Antúnez, F. R. Harker, and G. Ares. 2018b. “Buy, Eat or Discard? A Case Study with Apples to Explore Fruit Quality Perception and Food Waste.” Food Quality and Preference 69: 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.05.004.

- Kaye-Blake, W., K. Bicknell, and C. Saunders. 2005. “Process versus Product: Which Determines Consumer Demand for Genetically Modified Apples?” The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 49 (4): 413–427. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8489.2005.00311.x.

- Kragt, M. E. 2013. “Stated and Inferred Attribute Attendance Models: A Comparison with Environmental Choice Experiments.” Journal of Agricultural Economics 64 (3): 719–736. doi:10.1111/1477-9552.12032.

- Krinsky, I., and A. L. Robb. 1986. “On Approximating the Statistical Properties of Elasticities.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 68(4): 715–719. Stable URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/1924536

- Kulikovskaja, V., and J. Aschemann-Witzel. 2017. “Food Waste Avoidance Actions in Food Retailing: The Case of Denmark.” Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 29 (4): 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2017.1350244.

- Kyutoku, Y., N. Hasegawa, I. Dan, and H. Kitazawa. 2018. “Categorical Nature of Consumer Price Estimations of Postharvest Bruised Apples.” Journal of Food Quality V(2018): 6. Article ID 3572397. doi:10.1155/2018/3572397.

- Lancaster, K. 1966. “A New Approach to Consumer Theory.” The Journal of Political Economy 74 (2): 132–157. doi:10.1086/259131.

- Lancsar, E., and E. Savage. 2004. “Deriving Welfare Measures from Discrete Choice Experiments: Inconsistency Between Current Methods and Random Utility and Welfare Theory.” Health Economics 13 (9): 901–907. doi:10.1002/hec.870.

- Loebnitz, N., and K. G. Grunert. 2015. “The Effect of Food Shape Abnormality on Purchase Intentions in China.” Food Quality and Preference 40: 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.08.005.

- Louis, D., and C. Lombart. 2018. “Retailers’ Communication on Ugly Fruits and Vegetables: What are consumers’ Perceptions?” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 41: 256–271. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.01.006.

- Mahé, T. 2010. “Are Stated Preferences Confirmed by Purchasing Behaviours? The Case of Fair Trade-Certified Bananas in Switzerland.” Journal of Business Ethics 92 (S2): 301–315. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0585-z.

- Mahieu, P. A., P. Rierra, and M. Giergiczny. 2012. “The Influence of Cheap Talk on Willingness-To-Pay Ranges: Some Empirical Evidence from a Contingent Valuation Study.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 55 (6): 753–763. doi:10.1080/09640568.2011.626524.

- Mazur, K., and J. Bennett. 2009. “Scale and Scope Effects on communities’ Values for Environmental Improvements in the Namoi Catchment: A Choice Modelling Approach.” Environmental Economics Research Hub Research Report No 42. http://www.crawford.anu.edu.au/research_units/eerh/publications/.

- McCluskey, J. J., R. C. Mittelhammer, A. B. Marin, and K. S. Wright. 2007. “Effect of Quality Characteristics on Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Gala Apples.” Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 55 (2): 217–231. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7976.2007.00089.x.

- McFadden, D. 1974. “Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behaviour.” In Frontiers in Econometrics, edited by P. Zarembka, 105–142. New York: Academic Press.

- McFadden, D. 1986. “The Choice Theory Approach to Market Research.” Marketing Science 5 (4): 275–297. doi:10.1287/mksc.5.4.275.

- Miller, S., P. Tait, C. Saunders, P. Dalziel, P. Rutherford, and W. Abell. 2017. “Estimation of Consumer Willingness-To-Pay for Social Responsibility in Fruit and Vegetable Products: A Cross-Country Comparison Using Choice Experiments.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 16 (6): 13–25. doi:10.1002/cb.1650.

- Moser, R., and R. Raffaelli. 2012. “Consumer Preferences for Sustainable Production Methods in Apple Purchasing Behaviour: A Non-Hypothetical Choice Experiment.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 36 (2): 141–148. doi:10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01083.x.

- Novotorova, N. K., and M. A. Mazzocco. 2008. “Consumer Preferences and Trade-Offs for Locally Grown and Genetically Modified Apples: A Conjoint Analysis Approach.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 11 (4): 31–53.

- Plazzotta, S., L. Manzocco, and M. C. Nicoli. 2017. “Fruit and Vegetable Waste Management and the Challenge of Fresh-Cut Salad.” Trends in Food Science and Technology 63: 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.02.013.

- Revelt, D., and K. Train. 1998. “Mixed Logit with Repeated Choices: Households’ Choices of Appliance Efficiency Level.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 80 (4): 647–657. doi:10.1162/003465398557735.

- Roodhuyzen, D. M. A., P. A. Luning, V. Fogliano, and L. P. A. Steenbekkers. 2017. “Putting Together the Puzzle of Consumer Food Waste: Towards an Integral Perspective.” Trends in Food Science and Technology 68: 37–50. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.07.009.

- Rousu, M. C., and J. R. Corrigan. 2008. “Consumer Preferences for Fair Trade Foods: Implications for Trade Policy.” Choices 23 (2): 53–55.

- Ruto, E., G. Garrod, and R. Scarpa. 2008. “Valuing Animal Genetic Resources: A Choice Modelling Application to Indigenous Cattle in Kenya.” Agricultural Economics 38 (1): 89–98. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00284.x.

- Ryen, E., and C. W. Babbitt. 2022. “The Role of U.S. Policy in Advancing Circular Economy Solutions for Wasted Food.” Journal of Cleaner Production 369: 133200. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133200.

- Sackett, H., R. Shupp, and G. Tonsor. 2012. Discrete Choice Modelling of Consumer Preferences for Sustainably Produced Steak and Apples. AAEA/EAAE Food Environment Symposium 123517. Agricultural and Applied Economics Association.

- Scarpa, R., T. J. Gilbride, D. Campbell, and D. A. Hensher. 2009. “Modelling Attribute Non-Attendance in Choice Experiments for Rural Landscape Valuation.” European Review of Agricultural Economics 36 (2): 151–174. doi:10.1093/erae/jbp012.

- Scarpa, R., M. Thiene, and K. Train. 2008. “Utility in Willingness to Pay Space: A Tool to Address Confounding Random Scale Effects in Destination Choice to the Alps.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 90 (4): 994–1010. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2008.01155.x.

- Scarpa, R., R. Zanoli, V. Bruschi, and S. Naspetti. 2013. “Inferred and Stated Attribute Non-Attendance in Food Choice Experiments.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 95 (1): 165–180. doi:10.1093/ajae/aas073.

- Schanes, K., K. Dobernig, and B. Gozet. 2018. “Food Waste Matters - a Systematic Review of Household Food Waste Practices and Their Policy Implications.” Journal of Cleaner Production 182: 978–991. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.030.

- Skreli, E., and D. Imami. 2012. “Analysing Consumers’ Preferences for Apple Attributes in Tirana, Albania.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 15 (4).

- Stewart, P., and S. Globig, edited by. 2011. Phytopathology in Plants. Canada: Apple Academic Press, Incorporated. Oakville.

- Symmank, C., S. Zahn, and H. Rohm. 2018. “Visually Suboptimal Bananas: How Ripeness Affects Consumer Expectation and Perception.” Appetite 120: 472–481. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.002.

- Tait, P., C. Saunders, and M. Guenther. 2015. “Valuing Preferences for Environmental Sustainability in Fruit Production by United Kingdom and Japanese Consumers.” Journal of Food Research 4 (3): 46. doi:10.5539/jfr.v4n3p46.

- Talia, E., M. Simeone, and D. Scarpato. 2019. “Consumer Behaviour Types in Household Food Waste.” Journal of Cleaner Production 214: 166–172. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.216.

- Thurstone, L. L. 1927. “A Law of Comparative Judgment.” Psychological Review 34 (4): 273–286. doi:10.1037/h0070288.

- Train, K., and M. Weeks. 2005. “Discrete Choice Models in Preference Space and Willing-To-Pay Space.” In Applications of Simulation Methods in Environmental and Resource Economics, edited by R. Scarpa and A. Alberini, chapter 1, 1–16. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Publisher.

- Tully, S. M., and R. S. Winer. 2014. “The Role of the Beneficiary in Willingness to Pay for Socially Responsible Products: A Meta‐analysis.” Journal Retailing 90 (2): 255–274. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2014.03.004.

- UN. 2015. United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1. United Nations General Assembly. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly. United Nations, New York. Available at https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- USAA. 2022. United States Apple Association Industry at a Glance. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://usapple.org/industry-at-a-glance

- USDA. 2019. United States Standards for Grades of Apples. United States Department of Agriculture. Downloaded from on May 17th, 2022. https://www.ams.usda.gov/grades-standards/apple-grades-standards

- USDA NASS. 2021. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service Apples Statistics. on May 17th, 2022. Downloaded from https://www.nass.usda.gov

- van Giesena, R. I., and I. E. de Hooge. 2019. “Too Ugly, but I Love Its Shape: Reducing Food Waste of Suboptimal Products with Authenticity (And Sustainability) Positioning.” Food Quality and Preference 75: 249–259. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.02.020.

- Wang, Q., J. Sun, and R. Parsons. 2009. “Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Locally Grown Organic Apples: Evidence from a Conjoint Study.” Hortscience 45 (3): 376–381. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.45.3.376.

- Wedel, M., and W. Kamakura. 2000. Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.