VISIONS OF BLACKNESS IN AMERICA TODAY REFLECT A SOCIETY THAT DOES NOT VALUE BLACK EXISTENCE. Daily, Americans can flip through the latest news cycles on television, or view the most recent viral video and see young Black women slammed to the ground by police officers; Black trans-gender women violently assaulted and murdered in the streets; unarmed Black men and boys shot inside their homes, backyards, and schools; and churches and synagogues ambushed and sprayed with bullets by White domestic terrorists. As a Black woman in the United States, it has become nearly impossible to imagine what the future holds for all Black Americans.

Every day, there are new tragic events that lead me to believe that we are in a 21st-century dystopia of racial hate. My reprieve from these futureless visions has only come during engagements with the arts, specifically art created by Black artists who center Blackness and Afrodiasporic histories. In September 2018, I served as a community docent for Mickalene Thomas’s exhibition, I Can’t See You Without Me, at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. For an hour, a couple of times a week, I was in the presence of Mickalene’s muses, all Black women, different shades of brown, who made me feel strong, visible, relevant, and central to all existence, past, present, and future. Thomas’s aesthetics, patterns, and materials felt like home, and she offered a future in which Black women could assertively and inconsequently stare back into the eyes of White audiences who gazed on them and judged their brown skin. A similar liberating aesthetic experience happened in January 2019 while I attended a live jazz performance by musical artist Mark Lomax. Lomax’s work, entitled “400: An Afrikan Epic,” had three movements that told “the story of black America stretching from Pre-colonial Afrika, through the 400 years after the start of the Transatlantic slave trade in 1619, and into the Afrofuture while celebrating the creativity of a people who continue to endure” (MarkLomax.com, Citation2019, para. 2). Lomax’s musical arrangements guided me on a contemplative, imaginary journey about the past, before slavery; the present; and, most importantly, the future, which situated Africa at the center of all human advancements. The rhythms and syncopations of Lomax’s compositions lifted my spirit to another land, to soil that felt comfortable and safe and mine to sow for future generations.

Love (Citation2019) stated that “for dark people, the very basic idea of mattering is sometimes hard to conceptualize when your country finds you disposable” (p. 2). Both Thomas and Lomax’s art presents a future in which Black Americans are healed from racial, social, and economic violence and are living healthy lives, flourishing, and united through African diasporic ideals. Although Afrofuturism’s theoretical frame is much more complex, this revolutionary vision of the future is at its core. In this article, I introduce Afrofuturism as a futuristic philosophy for an art curriculum for Black existence. Considering present-day social issues, the art curriculum should support Black students’ basic ability to see their futures not only in the arts, but in the world at large. Afrofuturism can provide a grounded foundation underneath Black students’ feet. To support this assertion, I explicate Afrofuturism’s conceptual framework and the ways it provides an orientation toward the future, even when one is hard to envision. Then, I detail Afrofuturism’s historical alignment with the arts. These articulations support the final section of this article, in which I use Afrofuturism to reimagine the art curriculum so that it offers more opportunities for Black students to visualize themselves in this world beyond the present day.

What Is Afrofuturism?

In 1994, cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term “Afrofuturism” to refer to “speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture—and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future” (p. 180). Dery’s primary conceptualization of Afrofuturism was situated in Black people’s relationship with science fiction and technology, but epistemologically, the term speaks to the future of Black people in general. In his theorizing of Afrofuturism, Dery (Citation1994) questioned the possibility of the Black community even being able to imagine futures because of the intentional mass elimination of their past by Northern White Europeans. Dery (Citation1994) explained,

The historical reason that we’ve been so impoverished in terms of future images is because, until fairly recently, as a people we were systematically forbidden any images of our past. I have no idea where, in Africa, my black ancestors came from because, when they reached the slave markets of New Orleans, records of such things were systematically destroyed. (pp. 190–191)

Nevertheless, Dery (Citation1994) relented, Black people still have legitimate stories to tell about culture, technology, and what is to come. However, recognizing that there is limited access to stories about African people from the Middle Passage or before, Afrofuturism requires a deviation from anthropological and historiographic resources to develop “past-future visions” (Nelson, Citation2000, p. 35), and thus ventures into “the realm of fantasy and myth to compensate for the lack of concrete and indubitable material” (Mayer, Citation2000, p. 557).

Since Afrofuturism’s introduction to the academic discourse by Dery (Citation1994), numerous scholars have adopted variations of the concept that expand its ideological impact beyond the sci-fi context. For example, building off of Dery’s work, Kodwo Eshun (Citation2003) characterized Afrofuturism as “a program for recovering the histories of counter-futures” that were created to antagonize Afrodiasporic projections (p. 301). Eshun (Citation2003) claimed that Afrofuturism’s priority is for Africa to increasingly become the foundational site for futuristic interventions that impact political and social power. Expanding Dery and Eshun’s work even further, Susana Morris (Citation2012) aligned Afrofuturism with Black feminist thought, as both frames underscore the centrality of Blacks to future knowledge and cultural production and resistance to tyranny. Overall, contemporary Afrofuturists have a unifying commitment to use the precolonial histories of African people to envision postcolonial futures with Africa at the center.

Afrofuturism and the Arts

Dery (Citation1994) asked, “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?” (p. 180). In short, the answer is yes, and the arts have been integral in doing so. Although the term Afrofuturism was coined in 1994, literary, musical, and visual artists have been developing futuristic images of Blackness that center the African diaspora for a substantial amount of time.1 These artists, who range across all types of media, are connected by their larger aesthetic mode that projects Black futures derived from Afrodiasporic experiences (Elia, Citation2014; Yaszek, Citation2006). Elia (Citation2014) explained,

The creative contribution of Afrofuturist writers, musicians, artists, filmmakers and critics challenges the stereotypical historical view that was routinely applied to the Black Atlantic experience and proposes counter-histories that reconsider the role of black people in Western society in the past and imagine alternative roles in the future. (pp. 83–84)

Speaking explicitly to the visual arts, numerous scholars (Cui & Wiswell, Citation2015; Dery, Citation1994; Elia, Citation2014) cite Jean-Michel Basquiat’s artistic contributions as Afrofuturistic exemplars, as his work legitimized “a progressive and futuristic vision of the African-American community” (Elia, Citation2014, p. 89). Basquiat’s abstract expressionism (re)imagined and (re)presented Black futures, as can be seen in his 1983 work titled Molasses. Cui and Wiswell (Citation2015) explained further,

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work, “Molasses,” features a derelict-looking robot resigned at the foot of a uniformed human figure driving a vehicle with bars, a jail on wheels. “Molasses” is a likely reference to the slave trade, which produced sugar (and molasses as a marketable byproduct). Slaves, considered property rather than human beings, are made analogous to the robot, suffering at the hands of an authoritative “higher” being. In this way, Basquiat reinvents events of the past through a lens from the future, exemplifying a core tenet of afrofuturism. (para. 6)

As seen in Basquiat’s work, the arts have historically aligned with Afrofuturism’s aim to produce disruptions to the present that force a reimagining of the future (Eshun, Citation2003).

African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA) is another example of the arts’ historical alignment with Afrofuturism. AfriCOBRA, conceived in 1968, is an African American artists’ collective that was formed in Chicago, Illinois, by five founding members, Jeff Donaldson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, Barbara J. Jones (Hogu), and Gerald Williams. AfriCOBRA, which foregrounds Afrofuturism, aimed to develop a communal, recognizable aesthetic, a shared visual language, that would communicate positive revolutionary ideas about Black art and Black futures. As a response to being locked out of the Western contemporary art world, AfriCOBRA executed an intervention that was central in helping shape the Black Arts Movement (Jones-Hogu, Citation2012). The group conceptualized their own art philosophical concepts and aesthetic principles (e.g., luminosity, free symmetry, color) that considered the multidimensionality of Black existence and African origin. By considering and developing a characteristically Black style in the visual arts, AfriCOBRA staked a claim for Black artists to exist in the future, regardless of mainstream acceptance. What can these past manifestations of Afrofuturism within the visual art world offer art educators’ imaginations regarding a future art curriculum?

Art educators need to consider how we can develop a future art curriculum that results in our Black students identifying art as a primary means to envision their futures.

Afrofuturism and a Future Art Curriculum

Basquiat, as well as the founding members of AfriCOBRA, challenged the invisibility of Black artists in the contemporary art world writ large. Similarly speaking to invisibility, many art education scholars have written about the need for all students, especially students of color, to see themselves in the curriculum that art teachers develop and the resources that they use in the classroom (Acuff, Citation2018; López, Pereira, & Rao, Citation2017; Sions, Citation2019). However, further, I argue that in our contemporary social climate, we should want students to not only see themselves in the art curriculum but also be able to imagine and develop their futures through the art curriculum. Art educators need to consider how we can develop a future art curriculum that results in our Black students identifying art as a primary means to envision their futures.

An art curriculum includes not only daily art activities but things such as the aesthetics we embrace, the media we validate, the language we use, and the way we nurture students’ artist identities. What might these aspects of an art curriculum look like with Afrofuturism at the helm? I assert that an Afrofuturist art curriculum, including aesthetics, media, and language, can help reimagine art discourses and develop counterpractices that decenter Whiteness and transform the way Black students speak themselves into existence in the future [art] world.

Aesthetics

“Afrofuturism as a design lens facilitates a more empathic design engagement that explicitly places the often disenfranchised Black voice central in the design narrative, with an intent of universal betterment through and by technology” (Winchester, Citation2018, para. 6). Marvel’s superhero blockbuster film Black Panther is the most recent mainstream illustration of such design engagement. Seen prominently in the film’s costume design and setting of Wakanda, a fictional African nation at the precipice of technological advancement, the Afrofuturist aesthetic speaks to the intersections of Black cultures, liberation, imagination, and technology (Winchester, Citation2018). Inspired by various cultures throughout the continent, Black Panther intentionally aimed to illustrate the true diversity of Africa. Ruth E. Carter, Black Panther’s costume designer, and Hannah Beachler, the film’s production designer, were heavily influenced by their travel to different regions of the African continent, meeting African peoples such as the Maasai (Kenya and Tanzania), the Himba (northern Namibia), the Dogon (Mali, West Africa), the Tuareg (Sahara region of North Africa—Niger, Mali, Libya, Algeria, Burkina Faso), and the Basotho (South Africa). Carter communicated her desire to “respect” and “preserve” the complexity of African culture through costume design (Goodman-Hughey, Citation2018). As a result of her commitment, even the fictional technologies, like the superpower Vibranium Kimoyo Beads that adorned the wrists of characters, were inscribed with Nigerian Nsibidi symbols. Thus, functioning as futuristic communication devices that made and received virtual calls, controlled machines like the Royal Talon Fighter (Wakanda’s Air Force One), and accessed T’Challa’s throne room, the Vibranium Kimoyo Beads were quintessentially Afrofuturistic (Johnson, Citation2018).

In a movie about a futuristic, technologically advanced world, we see signs and signifiers that are markedly African, like Okavango (named after the Botswanan River) patterns on the Black Panther’s suit and Ghanaian Adinkra symbols on garments throughout the film. Carter asserted, “We weren’t trying to be ‘African-inspired.’ We were trying to build a distinctly African futuristic movie” (Carter, as cited in Horne, Citation2018, para. 8). Black Panther’s Afrofuturist ideological lens, illuminated through design and aesthetics, inspired a brighter future for Black communities around the world (Wallace, Citation2018).

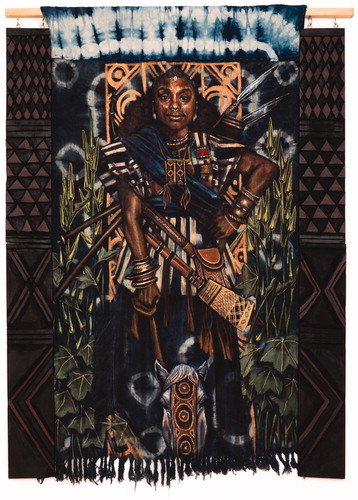

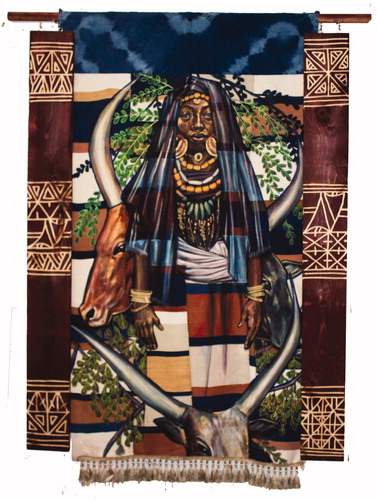

Afrofuturist aesthetics can also be identified in the multimedia work of Black visual artist Stephen Hamilton (). In one of his major installation series, Founders Project, Hamilton reimagines Black Boston public high school students as “the legendary progenitors of West and Central African ethnic groups that are ancestral to the African diaspora” (Gray, Citation2018, para. 3). The Founder’s Project, which was birthed from Hamilton’s desire to address the lack of precolonial African narratives in mainstream educational discourse, is saturated with messages about the strength, vibrancy, and potential leadership of today’s Black American youth (The Itan Project, Citation2018).

Figure 1. Ruth Ayuso as Nnimm Woman Descending, 2018. Acrylic, brass, and natural dyes and pigments on wood and hand-woven cloth. 72 inches × 72 inches. A depiction of Boston high school student Ruth Ayuso as the founder of Nnimm women’s society of the Ejagham people (Southeast Nigeria).

Figure 2. Gianna Watson as Yennenga, 2018. Acrylic and natural dyes and pigments on wood and hand-woven cloth. 60 inches × 72 inches. A depiction of Boston high school student Gianna Watson as Yennenga, founder of the Mossi Empire (Burkina Faso, West Africa).

Figure 3. Salamata Barry as Bajemongo, 2018. Acrylic and natural dyes and pigments on wood and hand-dyed cloth. 60 inches × 72 inches. A depiction of Boston high school student Salamata Barry as the matriarch of the Fulani people (concentrated principally in Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, Niger, Cameroon, and Guinea).

Hamilton’s commanding visual statements about Boston’s Black youth are contemporary, yet situated tidily in ancient African aesthetics and mythological plots. Hamilton’s personal website2 describes his work more in-depth:

Through visual comparison of shared philosophies and aesthetics amongst Black peoples, he seeks to describe a complex and varied Black aesthetic. These visual and philosophical connections and cultural analyses form his visual language. The pieces created depict African thought and culture as equal to, yet unique from, its western analog. This work stands in stark contrast to the pervasive negative associations, which have become synonymous with Black culture. [Hamilton’s] work, therefore, bridges dialogue between contemporary Black cultures and the ancient African world through an asset-based lens. (para. 1)

While his aesthetics give a nod to his ancestral past, Hamilton’s conceptual framework is futuristic in that it “reconsider[s] the condition of people of the black diaspora in the new millennium” (Elia, Citation2014, p. 87). Developing a future art curriculum that centers Afrofuturist aesthetics, which illustrate the multiplicity and complexity of artistic designs that live in Africa, can offer Black students opportunities to construct new ways of existing and invent new ways to visually present themselves, as illustrated in Hamilton’s work.

Media

Teachers’ emphasis on certain media and artmaking processes in the classroom communicates messages to students about their significance in the art world writ large. For example, textiles and fiber arts such as weaving and quilting, as well as woodwork and metalwork (often pejoratively labeled as “crafts”), have a marginalized position in the U.S. contemporary art world, and thus, in art classrooms (Markowitz, Citation1994). “Crafts,” which are grounded in community and shared kinship (Katter, Citation1995), are most often associated with the artmaking practices of indigenous communities of color. The unique characterizations of “art” versus “craft” in the US are connected to a larger systemic classification situated within Whiteness and patriarchy, illuminating the power and authority at work in the art field (Ługowska, Citation2014).

Afrofuturism requires art teachers to rethink the media that they covet in their art curriculum. A future art curriculum cannot be led by Western ideals that continue to dichotomize “arts” and “crafts,” thus marginalizing non-Western media and artmaking practices, like those utilized by Hamilton in Founder’s Project. Hamilton uses traditional materials, patterns, and techniques employed by Yoruba, Igbo, Edo, Nupe, Tiv, and Ebira weavers to create his multimedia art (). Hamilton (as cited in Gray, Citation2018) explains his focus on African craftsmanship: “The idea is to pay homage to the ancestors by making this work in the way that they would have made it.… I wanted to pay homage to black hands” (para. 3).

Figure 4. Stephen Hamilton working with fiber and textiles in his studio. “Each textile is made on the Nigerian upright loom using patterns and techniques employed by Yoruba, Igbo, Edo, Nupe, Tiv, and Ebira weavers. All yarn is hand-dyed using only natural dyes” (personal communication, June 25, 2019).

Reimagining an art curriculum with an Afrofuturist frame can result in Black students making Afrodiasporic connections and building bridges across generations and ancestry. Such positive identification with a community through racial and ethnic socialization often results in children’s stronger sense of self, thus making it easier for them to thwart negative representations that circulate in mass media and visual culture (APA, Citation2008). Afrofuturism makes an intervention in our conceptions of the present by retrieving historical information to conceive the future.

Language

Historically, language has been a tool central to the production of racial inequity (Fanon, Citation2008). Afrofuturism supports the (re)invention of a visionary discourse that reflects the complex negotiation of power sharing (David, Citation2007; Morris, Citation2012). A future art curriculum undergirded by Afrofuturism assumes language that offers futurist solutions to rejecting cultural subjugation, racism, and heteropatriarchy in our classrooms. For example, the concept of the “old masters,” which art teachers refer to when discussing Western canonical artists, is problematic and loaded with violent, oppressive historical memories for some groups of people. For example, as a Black woman in the US, when I hear the word “master,” regardless of context, I immediately think about European White men who enslaved, tortured, raped, and sold African people like material goods hundreds of years ago. To further the narrative that equates “master” to Whiteness, in the art classroom, a “master” was never revealed by any teacher or textbook to be a person of African descent. Even the corporations that supply our teaching materials (e.g., art posters) follow the narrative that excludes people of color as art “masters” (Buffington, Citation2019). Therefore, as a Black woman, under no circumstances have I ever identified myself as a “master” or even having the ability to be a “master” in the art world in the future. This is illustrative of how language can impact Black students’ artistic futures, specifically their identity development as artists. The word “master” furthers a hierarchy of power that art educators should no longer want to support in a future art curriculum. To be clear, though, the absence of the word “master” will not result in the immediate destabilization of the racial power structure it represents; however, Afrofuturism is about the utopian formulation of a possible model of something that does not yet exist. Re-envisioning semantics in our future art curriculum is key to transgressing repressive social norms and power systems that subjugate Black students.

A future art curriculum cannot be led by Western ideals that continue to dichotomize “arts” and “crafts,” thus marginalizing non-Western media and artmaking practices.

Critical Considerations for Afrofuturism in a Future Art Curriculum

An Afrofuturistic art curriculum explores “futuristic counternarratives that speak to the intersections of history and progress, tradition and innovation, technology and memory, the authentic and engineered, analog and digital within spaces of the diasporic culture” (David, Citation2007, p. 698). Afrofuturism in art education must not be mistaken for liberal multiculturalism in which teachers simply add African artists to an already established art curriculum in the name of visibility. Afrofuturism in an art curriculum is not African mask-making to teach cultural appreciation or using construction paper to create kenté cloth patterns to introduce a singular African aesthetic. In actuality, such projects have the capability to exoticize and homogenize Africa and perpetuate a primitive designation of the continent, instead of placing it at the forefront of worldwide technological and human advancements (Acuff, Citation2014). It is critical to remember that Afrofuturism does not leave Africa in the past in the ways that liberal multiculturalism often does to most non-Western, nonsecular-derived cultures. Instead, Afrofuturism identifies the Afrodiasporic past as a way to present the future of all of humanity. Thus, for example, an Afrofuturistic art curriculum may include a unit that is conceptually futuristic, situated in fantasy, myth, and imagination but that utilizes traditional African diasporic artmaking processes. This securely places Africa, and consequently, students of African descent, in the future, a technologically advanced universe. Our art curriculum has the potential to expose and reframe futurisms that resolve Black students’ dystopia and forecast meaningful existence (Eshun, Citation2003).

Afrofuturism has been used as a methodological tool for Black liberation (Duyst-Akpem, Citation2017), and thus can significantly influence the way a future art curriculum can function in the classroom. Celebrated Afrofuturist artist and educator D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem (Citation2017) wrote,

By centering and studying in earnest the creative representations of place and community in African Diasporic and Indigenous works, we move past ingrained Eurocentric notions of how things “should” be or how things are, and open space to imagine ourselves in the future which brings students back to the present, to their own agency as they see themselves reflected. (para. 8)

The current 21st-century racial, political, and economic climate requires art educators, and thus our curriculum, not only to provide our students with access to the arts, but to demonstrate how the arts can be used to access the future. With care, attention, and intentionality, systemic violence inflicted on the minds and bodies of our Black youth can be countered in our art classrooms. To begin, art teachers need to (re)consider the aesthetics, media, and language that we assume and present to our students. Decenter Western aesthetics by normalizing the multidimensional, varying aesthetics that live throughout Africa. Destabilize the craft narrative associated with certain media by initiating ongoing engagements with materials and processes conceived by different African nations. Further, use affirming language that empowers Black students to see themselves as artists, creatives, and originators of form. These Afrofuturist tools give Black students the agency to actively create their existence and futures. Afrofuturists “are creating the potentiality for self-realization in a future social reality that makes space for [Black people] to be safe within our own bodies” (Freeman, Citation2015, para. 22). With Afrofuturism undergirding the future art curriculum, students will be able to use art to affirm their existence, as well as envision a world where colonialism and its effects are no longer a limitation to creating a Black-centric future.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joni Boyd Acuff

Joni Boyd Acuff, Associate Professor, Arts Administration, Education & Policy, The Ohio State University in Columbus. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 For example, many of Black female literary artist Octavia Butler’s writings have become synonymous with Afrofuturism. W. E. B. Du Bois and Ralph Ellison have also been named Afrofuturist authors by scholars (Dery, Citation1994; Elia, Citation2014). Musical artists Sun Ra and George Clinton are touted as Afrofuturist. Visual art examples that embody Afrofuturism “can also be traced in the graffiti and performance art by Rammellzee, in the installations by Charles H. Nelson, in the photography of Renée Cox and Fatimah Tuggar, in the paintings with black astronauts by David Huffman, in the sculptures by Bodys Kingelez and in some comics and videogames” (Elia, Citation2014, p. 89). These artists’ works consider and reflect on the extraordinary histories and traditions of the African diasporic culture, but then expand these traditions, thus resulting in past-future visions (Nelson, Citation2000).

References

- Acuff, J. B. (2014). (mis)Information highways: A critique of online resources for multicultural art education. International Journal of Education Through Art, 10(3), 303–316.

- Acuff, J. B. (2018). Confronting racial battle fatigue and comforting my Blackness as an educator. Multicultural Perspectives, 20(3), 174–181.

- American Psychological Association (APA), Task Force on Resilience and Strength in Black Children and Adolescents. (2008). Resilience in African American children and adolescents: A vision for optimal development. Washington, DC. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/resiliencerpt.pdf

- Buffington, M. (2019). Whiteness is. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 36(2), 10–27.

- Cui, A., & Wiswell, J. (2015). Science fiction and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “Molasses.” Retrieved from www.voyagesjournal.com/future/science-fiction-and-jean-michel-basquiats-molasses [Website no longer functions].

- David, M. (2007). Afrofuturism and post-soul possibility in Black popular music. African American Review, 41(4), 695–707.

- Dery, M. (1994). Black to the future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose. In M. Dery (Ed.), Flame wars: The discourse of cyberculture (pp. 179–222). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Duyst-Akpem, D. D. (2017). Pedagogy. Place. Liberation [Web page]. Retrieved from https://placelab.uchicago.edu/site-blog/denenge-post/1/24/2017

- Elia, A. (2014). The languages of Afrofuturism. Lingue e Linguaggi, 12, 83–96.

- Eshun, K. (2003). Further considerations of Afrofuturism. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(2), 287–302.

- Fanon, F. (2008). Black skin, white masks (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Freeman, M. I. J. (2015). The invisible future in our present (Black existentialism part 3) [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@amai.m.i.freeman/the-invisible-future-in-our-present-black-existentialism-part-3-3a3ddeae9da5

- Goodman-Hughey, E. N. (2018, February 1). “Black Panther” costume designer Ruth E. Carter on creating the wardrobe for Wakanda. ESPN. Retrieved from www.espn.com/espnw/culture/article/22288799/black-panther-costume-designer-ruth-e-carter-creating-wardrobe-wakanda

- Gray, A. (2018, November 15). This artist reimagines Black and Brown youth as African Royalty. The Artery. Retrieved from www.wbur.org/artery/2018/11/15/stephen-hamilton-reimagines-black-and-brown-youth-as-african-royalty-founders-project

- Horne, K. (2018, February 15). Black Panther designer Ruth Carter reveals the African symbols embedded in the costumes [Blog post]. Retrieved from www.syfy.com/syfywire/black-panther-designer-ruth-carter-reveals-the-african-symbols-embedded-in-the-costumes

- “The Itan Project: The Art of Stephen Hamilton.” (2018, November 15). WBUR. Retrieved from www.wbur.org/artery/2018/11/15/stephen-hamilton-reimaginesblack-and-brown-youth-as-africanroyalty-founders-project

- Johnson, V. (2018, March 1). Breaking down the futuristic technology of “Black Panther” [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://mashable.com/2018/03/01/black-panther-technology/

- Jones-Hogu, B. (2012, January 8). The history, philosophy and aesthetics of AFRICOBRA [Blog post]. Retrieved from www.areachicago.org/the-history-philosophy-and-aesthetics-of-africobra

- Katter, E. (1995). Multicultural connections: Craft & community. Art Education, 48(1), 8–13.

- López, V., Pereira, A., & Rao, S. S. (2017). Baltimore uprising: Empowering pedagogy for change. Art Education, 70(4), 33–37.

- Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Ługowska, A. (2014). The art and craft divide—on the exigency of margins. Art Inquiry. Recherches Sur Les Arts, 16, 285–296.

- MarkLomax.com. (2019, May 24). Concerts. Retrieved from https://marklomaxii.com/concerts

- Markowitz, S. J. (1994). The distinction between art and craft. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 28(1), 55.

- Mayer, R. (2000). “Africa as an alien future”: The middle passage, Afrofuturism, and postcolonial waterworlds. Amerikastudien/American Studies, 45(4), 555–566.

- Morris, S. M. (2012). Black girls are from the future: Afrofuturist feminism in Octavia E. Butler’s “Fledgling.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 40(3&4), 146–166.

- Nelson, A. (2000). Afrofuturism: Past-future visions. Color Lines (Spring), 34–37.

- Sions, H. (2019). Teaching about racially diverse artists and cultures (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Virginia Commonwealth University Archives, https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5795

- Wallace, C. (2018, February 12). Why “Black Panther” is a defining moment for Black America. The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2018/02/12/magazine/why-black-panther-is-a-defining-moment-for-black-america.html

- Winchester, W. W., III. (2018, March 24). Black Panther, engineering, and Afrofuturism [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.aaihs.org/black-panther-engineering-and-afrofuturism

- Yaszek, L. (2006). Afrofuturism, science fiction, and the history of the future. Socialism and Democracy, 20(3), 41–60.