Editorials, like art teaching, are written in anticipation of what is yet to come. As described in my earlier editorials, times of upheaval require us to untangle knotty networks of interruptions and disruptions as we seek opportunities in our teaching to foster sustainable, lifelong learning. The English word anticipate has its roots in the Latin word anticipare, which means “to take before,” with an original sense of “to cause to happen sooner.” By c. 1640, the word anticipate acquired the sense “to be aware of (something) coming at a future time.” In the context of education, anticipation refers to the latent nature of adaptation whereby in the present circumstances, we as educators are continually acclimatizing to our “new normal.”

Yet, as Elliot Eisner (Citation1985) continually reminded us, what we anticipate and plan for as art educators will always be enlivened by expressive outcomes that are unanticipated because “instructional objectives emphasize the acquisition of the known, while expressive objectives, emphasize its elaboration, modification, and at times, the production of the utterly new” (p. 56). The interplay in Eisner's words contextualizes the known and the unknown knowledge we rely on when we anticipate something. This knowledge, claimed Moser (Citation1999), is mostly tacit knowledge, which innately shares and shapes our beliefs, experiences, and actions—albeit becoming a key element in building agency through new experiences, and for educators, their effectual asset.

We concluded 2020 with some anticipation of “hope,” yet 2021 presented us with the unanticipated insurrection of the U.S. Capitol on January 6—reaffirming partisan politics, posing a threat to our nation's core: our democracy. Our fear of what to anticipate at the historic inauguration of the 46th president of the United States and welcoming the very first woman of color as vice president was further complicated after the insurrection. Similar to September 11, 2 decades ago, the day of January 6, 2021, became a frozen moment where “‘everything changed’” and “the freeze frame of hypnotic slow motion sharpened edges as much as blurred boundaries” (Sullivan, Citation2002, p. 107).Footnote1 Encouraging us to look at the big picture, Sullivan (Citation2002) asks, “What does the big picture reveal, and how might those of us charged with the task of teaching help to shape its making and understanding?” (p. 107). Here, I am reminded of Amanda Gorman's inaugural poem, “The Hill We Climb,” recited at the U.S. presidential inauguration on January 20, 2021. Her poem is a text about the future. She urges us to appreciate what stands before us rather than what stands between us. Both Sullivan (Citation2002) and Gorman (PBS NewsHour, Citation2021) call on educators to anticipate the big picture, which offers an array of possibilities and alternative perspectives whereby presenting opportunities for becoming agents of change as we step out of the recent past to become the future. In that sense, the commentaries and articles in this issue provide intellectual nourishment for anticipating what is yet to come becoming stepping‐stones to move forward.

In keeping with the tradition of various firsts of 2021, Manisha Sharma and Asavari Thatte, in the journal's first coauthored commentary from a South Asian perspective grounded in memories of their lived experiences, reveal a marked difference in what they learned at school and at home in India. Their commentary responds in anticipation to the present‐day discourse within the US on education centered around making. Sharma and Thatte deconstruct curricular approaches to Indian K–12 art, craft, and design education, focusing on how culturally specific international perspectives to arts education can be useful to art educators within and beyond nation‐based curricular contexts. In a similar vein, Christina D. Chin describes the unusual Fayum mummy portraits from Egypt as a way to see the complex diversity of ancient Egypt across numerous dimensions and understand artworks as amalgamations of many diverse influences, in lieu of stereotyping Egypt and its art. Chin calls us to embrace culturally relevant practices that foster understandings of the heterogeneity and hybridity of the individuals with whom we share this planet. All three scholars allude to the much‐anticipated need for the inclusion of the “other” in art education.

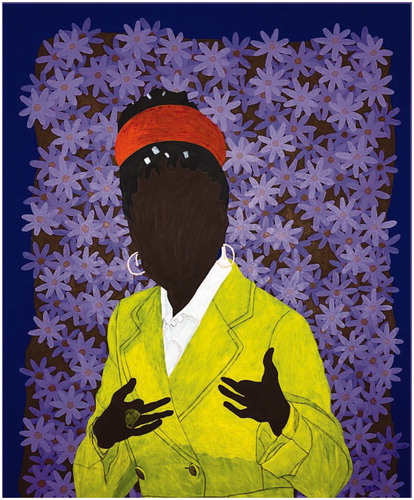

Raphael Adjetey Adjei Mayne, Amanda Gorman, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Destinee Ross‐Sutton. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/amanda-gorman-harvard-painting-gift-1940108.

Peaches Hash, in fear of anticipating the challenges faced by students when teaching platforms shifted from in‐person to online during COVID‐19, redesigned her curriculum to accommodate new experiences using expressive arts. She poses the question: How essential is art, especially during times of disrupted learning routines? Amber Ward and Jennifer L. Garcia discuss the unexpected disruption of distance from their classrooms, which robbed them of student–teacher connections, isolating them even further. In their effort to be resilient during adverse times, they anticipate a postpandemic art education that might offer us opportunities to meet different vantage points, goals, and needs with care. Paulina Camacho Valencia's commentary is a discussion in response to the current political moment, and the unanticipated global health crisis calls for a focused attention to break the silence from centuries of oppression, resonating with Amanda Gorman's call, “When day comes, we step out of the shade, aflame and unafraid” (as cited in PBS NewsHour, Citation2021, 5:15). When one reads these commentaries collectively, buried within is a call to action in response to the unanticipated where what stands between the possible and impossible of anticipation is our determination to move forward through practices of artmaking as stewardship of our students’ decision making, awareness, and compassion.

Mary N. Laube's use of the metaphor “two birds with one stone” indeed is an attempt to alter the way we teach art. She asks that we work toward creating a more equitable playing field for future artists through proactive initiatives in the classroom, where educators can reinforce a conduit between teaching art, making art, and the writing of its history. Her question is, How can we correct shortcomings of the past that overlook the problematics of underrepresentation? The distinct references here to “two birds with one stone” and “conduit” make the point that teaching takes on multiple and overlapping tasks where the expected and the unanticipated work hand in hand to surprising and meaningful ends.

Stephanie Baer and Mikayla Helton's article shares their unanticipated experiences of getting past the security gate of a youth treatment center, where they invite the reader to consider capitalizing on our strengths to help others during times of need to be that agent of change. Kathy Danko‐McGhee presents a teachable moment using a service‐learning opportunity where preservice teachers implemented an art and literacy curriculum for economically challenged infants and their families in an urban community center. Amanda Krantz and Stephanie Downey suggest that single‐visit art museum programs help students empathize with and tolerate difference while experiencing awe and broadening perspectives of what surrounds them. Although the unanticipated pandemic has changed how we can re‐create this experience, and while their article does not explicitly address this need, it is an open invitation to anticipate how one could reimagine and strengthen school–museum partnerships. All five of these authors offer intellectual nourishment for the unanticipated, relying on the power of possibility in building student agency. This stance echoes Palmer's (Citation1998) notion of learning as not merely an acquisition of knowledge, but rather a process of growth where teaching recognizes and nourishes trust and agency while anticipating what is yet to come.

Believing in the power of art, citizen artist vanessa german shares her thoughts about the significance of everyday objects with Sue Uhlig. german looks at an object to consider the layers of its information, use, and purpose, seeing it in conversation with its past, present, and future in the context of political, cultural, and spiritual real‐world uses and implications. She gives form and voice to her own understanding of freedom in anticipation of her creative process. german's work challenges us to anticipate and face the unanticipated realities of our own history, asking us to retain, release, or reimagine our worlds.

bell hooks (1994) argued that freedom in education gives teaching a performative act to create conditions for innovation and change when confronted with the unanticipated. These spontaneous shifts in turn become change agents in drawing out the unique element within our teaching and learning spaces where art pedagogy happens every day. In anticipation of what the summer of 2021 will bring, I keep coming back to Gorman's call to face a future, which currently is framed within the roots of capitalism, gender, oppression, class domination, liberation, collaboration, and praxis in teaching and learning, allowing us to anticipate possibilities of hope, because “history has its eyes on us” (as cited in PBS NewsHour, Citation2021, 3:22). In triangulating anticipation, adaptation, and intellectual nourishment, bell hooks (1994) eloquently depicts the classroom as the most profound space of possibilities. She invites us “to open our minds and hearts so that we can know beyond the boundaries of what is acceptable, so that we can think and rethink, so that we can create new visions” (p. 12)—indeed, opening the door to our imagination to anticipate a bigger picture where “we will not march back to what was but move to what shall be” (Gorman, as cited in PBS NewsHour, Citation2021, 3:58). ▯

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ami Kantawala

Ami Kantawala, Adjunct Associate Professor of Art and Art Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Notes

1 The September 11 attacks in the US are mostly referred to as 9/11. A series of four coordinated terrorist attacks by terrorist group al‐Qaeda against the US were made on the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, where 2,997 individuals were killed.

The insurrection of the U.S. Capitol was a deadly riot and violent attack on the country's democracy on January 6, 2021. This attack was carried out by a mob of supporters of the 45th president of the US to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election.

References

- Eisner, E. W. (1985). The art of educational evaluation: A personal view. Falmer Press.

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

- Moser, K. (1999). Knowledge acquisition through metaphors: Anticipation of self‐change at transitions from learning to work. In H. Hansen, B. Sigrist, H. Goorhuis, & H. Landolt (Eds.), Education and work: The end of a difference (pp. 141-152). Bildung Sauerländer.

- Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher's life. Jossey‐Bass.

- PBS NewsHour. (2021, January 20). WATCH: Amanda Gorman reads inauguration poem, “The Hill We Climb” [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/LZ055ilIiN4

- Sullivan, G. (2002). What is the big picture? [Editorial]. Studies in Art Education, 43(2), 107-108. https://doi-org.tc.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/00393541.2002.11651712