As we navigate the ever-shifting presence of global crises, increasingly diverse communities, and complex digital classrooms, a multitude of theoretical perspectives continues to illuminate our pathways. As educators, we draw inspiration from influential scholars, each making unique contributions to our educational consciousness and practices. W. E. B. Du Bois (Citation1926), a sociologist and civil rights activist, made lasting marks on our understanding of racial equality. Angela Davis (Citation2016), a philosopher, feminist, and political activist, further illuminates the intersectionality of race, class, and gender in America while spearheading prison abolition movements. Educational theorist Gloria Ladson-Billings (Citation1995) expands our focus on inclusivity and sheds light on the achievement gaps and inequities in education through her work on culturally relevant pedagogy. John Dewey’s (Citation1938) pragmatic philosophy of learning by doing still resonates in classroom settings today that advocate for active student engagement and individual agency. The profound link between the arts and education finds expression in the work of Maxine Greene (Citation2001), who campaigned for a curriculum founded on social imagination to foster creativity and critical thinking. The transformative power of the arts aligns with the strong advocacy of Elliot Eisner (Citation2002), who fuses the educational imagination with mindful learning in the arts to promote an integrated approach to teaching. Finally, our awareness of the pedagogical implications of digital technologies is expanded by Tony Bates (Citation2015), a key researcher in the realm of online and distance education. These perspectives compel us to think beyond traditional boundaries, recognizing the fluidity of art as a discipline and acknowledging the evolving complexities of teaching and learning in our diverse, interconnected worlds. As we grapple with the aftermath of a global pandemic and the effects of dominant social movements, the contributions of scholars like these become our lifeline as educators. They anchor us in foundational principles, concurrently encouraging innovation and adaptation to sustain our teaching and learning practices. They further highlight the distinct role of the arts as a means of expression, a critical lens into societal conditions, and an agent of change, resistance, and enablement.

In this issue of Art Education, the articles lead to pivotal questions: How can art impact societal change, as seen in the artworks of Black Power movement artists? How does an improvisational approach inspire teaching? How can we employ culturally relevant pedagogy and experiential learning theory to nurture equitable learning environments in a post-pandemic world? What role do online tools and technology play in advancing educational accessibility and adaptability? Further, how can concepts of self-discovery and social justice be integrated into teacher education programs? These articles push the boundaries of traditional perspectives, interweaving art, politics, education, and technology against a backdrop of prevailing social movements and pedagogical adaptations. They invite us to rethink the potential of art education as a responsive and sustaining force within society.

In his essay, “Criteria of Negro Art,” Du Bois (Citation1926) asserted, “All art is propaganda and ever must be” (sec. 29), emphasizing the inherent political nature of art. This claim is not just theoretical; it finds powerful expression and affirmation in Marie Huard’s article, “The Art of Black Power: Identity and Activism.” Du Bois’s and Davis’s (Citation2016) conceptualizations of art as a tool for capturing human complexity, political expression, and as an ideological weapon, become obvious in the images created by artists Emory Douglas, Betye Saar, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Elizabeth Catlett, and Barkley Hendricks.Footnote1 One can argue that their artistic responses were not isolated reactions, but active agents in shaping the very moments they were representing, serving as visual articulations of the many aspects of the Black Power movement—from community involvement to individual identity. Further, the importance of exposing students to a diverse range of artists, particularly those of color, is exemplified throughout this article. Huard also draws parallels between the Black Power movement and the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement, indicating the continued educational relevance of these artists and their work in contemporary discourse. The Black Lives Matter movement echoes the call of the Black Power movement to create a space for Black imagination, innovation, and joy. As art educators, we can play a significant role by sharing and engaging students with the works of Black artists (https://blacklivesmatter.com).

Jennifer R. Ferrari’s article, “‘Yes, Please!’ An Improvisational Framework for Contemporary Art Education,” finds resonance with Eisner’s (Citation2002) argument that artistic ways of thinking are essential in responding to the ambiguities and complexities of learning. Eisner’s emphasis on fostering cognitive and emotional intelligence in the arts aligns with Ferrari’s advocacy for an improvisational approach to teaching. In viewing education as an improvisational act rather than a scripted performance, both Eisner and Ferrari propose an education paradigm that affords students and teachers the autonomy to create, explore, and interpret their worlds, enabling them to author their educational narratives.Footnote2

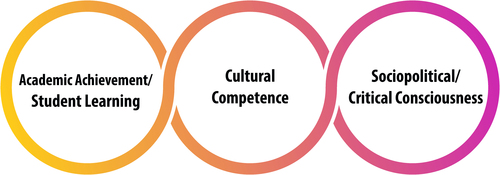

Che Sabalja’s article, “Reframing Art Teacher Practice: Dialogical Exploration During the Pandemic,” examines the construction of an equitable and engaging learning environment, a topic deeply aligned with the works of Ladson-Billings (Citation1995) and Dewey (Citation1938). Sabalja invites us to draw upon Ladson-Billings’s culturally relevant pedagogy and Dewey’s experiential learning theory to propose a contemporary art education framework capable of navigating post-pandemic remote learning challenges. Her approach constructs a learning community that values students’ cultural identities and experiences, fostering equity and enriched learning. The author’s practice of dissolving traditional student–teacher roles and promoting open-ended questioning and knowledge sharing aligns with Ladson-Billings’s model. It facilitates students in navigating their learning and understanding the world around them. Concurrently, the author’s pedagogical adaptation amid the pandemic resonates with Dewey’s (Citation1938) holistic, student-centric, experiential education philosophy. Sabalja’s effort to transform Zoom boxes into creative sanctuaries mirrors Dewey’s concept of unified, lived experiences, portraying learning as a dynamic, immersive process of “doing and undergoing.” Echoing Dewey’s (Citation1938) belief in the transformative power of everyday learning experiences, the author suggests that pandemic-era experiences could deepen students’ social connections and understanding. This belief is evident as students unveil reflective responses and contextualize emotions through art, engaging in transformative learning experiences. Sabalja demonstrates how the principles embraced by Ladson-Billings and Dewey can be embedded in a contemporary, virtual context, underscoring their enduring relevance in today’s educational landscape.

Tony Bates’s (Citation2015) insights about the transformative impact of technology in contemporary education illustrate the possibilities and challenges classroom teachers face in the shift from traditional to virtual classrooms. Bates champions the potential of online learning to enhance accessibility and adaptability in teaching, a common threat felt in these pandemic-era narratives of traditional-to-virtual classroom transition. These issues are taken up in “Bitmojis and Beyond: Incorporating the Studio Habits of Mind Into Online Art Instruction,” by Kayla Lindeman and Troy Hicks; “Expanding Creative Communities in the Visual Arts: Using Padlet to Support Student Engagement and Belonging in Stressful Contexts,” by Rhiannan Johnson, Kate Cantrell, Katrina Cutcliffe, Beata Batorowicz, and Tanya McLean; and “Stories of Online Art Education: Transitions and Challenges During the Pandemic,” by Borim Song, Maria Lim, and Kyungeun Lim.

The article “Bitmojis and Beyond” delves into the integration of Studio Habits of Mind in online art instruction, using Bitmoji classrooms as a case study. It highlights the efficacy of certain Studio Habits in virtual instruction and discusses implications for advocacy, habit internalization, and digital tool leverage. The unique potential of online platforms, as suggested by Bates, is exemplified in the article. The possibility of some Studio Habits finding a better fit in a digital setting underscores Bates’s proposition of unique teaching and learning opportunities offered by various technologies.Footnote3 This article also aligns with Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (Citation1983), highlighting the benefits of learner-centered and adaptive educational methods.Footnote4

The application of Bates’s (Citation2015) insights about online learning is also apparent in “Expanding Creative Communities in the Visual Arts.” Rhiannan Johnson and her coauthors describe how using Padlet fosters engagement, feedback, and personal reflection, facilitating the creation of virtual creative communities. This practical application applies Bates’s idea about the potential of technology in fostering collaborative learning environments. Also, the use of Padlet reflects Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (1978), emphasizing how scaffolding social learning contexts facilitates interactive dialogue in the co-construction of knowledge and skills.

In “Stories of Online Art Education,” Borim Song and her coauthors capture the transition to online instruction during the pandemic, echoing Bates’s (Citation2015) discourse on the dual nature of virtual classrooms. As Bates suggests, while such a transition can present logistical and pedagogical hurdles, it also reveals possibilities for innovative teaching strategies and broader accessibility. This article offers creative solutions, such as virtual guest speakers and video observations, illustrating the adaptability Bates advocates regarding online education. These considerations also resonate with Rolling’s (Citation2010) and Zander’s (Citation2007) emphasis on the significance of educators’ personal narratives, underlining the value of shared experiences and collaborative reflection in professional development. Collectively, these three articles capture Bates’s vision of how online learning intertwines theory and practice and provides actionable insights for navigating the challenges of virtual art instruction.

Juyoung Yoo and Megan Lucas-Chong’s article, “Art Pen Pal: Exchanging Art Letters With My International Friend,” aligns with Maxine Greene’s (Citation2001) belief about the potential of art as a medium for understanding and embracing diverse perspectives, and art education’s role in facilitating cultural exchange and community engagement. While exchanging art letters, children participated in a shared artmaking practice. Thus, they were not only learning to communicate and interact through creative visual language but also got a peek into their pen pal’s culture, language, and country. This process of mutual learning further embodies Greene’s (Citation2001) notion of art as a social construct and thus creates meaningful cross-cultural connections. Similarly, the article aligns with Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) sociocultural theory, emphasizing the vital role of social interaction in cognitive development. Creating and exchanging art represents this interaction, which, according to Vygotsky, is an essential component for learning and children’s development.

Journey alongside Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz in this issue’s interview feature, “Navigating the Self: A Path to Social Justice.” An educator, researcher, and fervent advocate for social justice, Sealey-Ruiz introduces us to the transformative concept of the Archaeology of Self. She deciphers the origins of this unique methodology for self-discovery and demonstrates how it aligns with her personal quest. Through the prism of racial literacy and social justice, she explores the importance of examining personal narratives and lived experiences, and their integration into teacher education curricula. This deep introspection draws parallels to Du Bois’s (Citation1903) concept of double consciousness, offering a critical lens through which we view and understand ourselves and our roles in a multicultural society. Echoing Davis’s (Citation2016) emphasis on the essential role of self-awareness and introspection, Sealey-Ruiz prompts us to contemplate how these qualities can foster a profound commitment to social justice. Her work pushes us to reconcile our inner selves with the external world, prompting change at both an individual and societal level. This ties back into Du Bois’s (Citation1903) assertions on the duality of self-perception, fostering a deeper understanding of our roles as educators and advocates for social justice.

In Sarah Travis’s instructional resource, “BE-ing Here With Transformative Artist Brandan ‘Bmike’ Odums,” she considers the transformational role of art, which sits well with John Dewey’s seminal text, Art as Experience (1934). Bmike, a Black American artist, uses art as a catalyst for change in spaces, objects, individuals, and communities, exemplifying Dewey’s (Citation1934) vision of practical knowledge and pragmatic outcomes. Bmike’s work further resonates with Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy (Citation1970) and Maxine Greene’s (Citation1995) concept of social imagination. His art stimulates societal change, reflecting Freire’s view of education as a tool for social transformation, and Greene’s (Citation1995) belief in the power of imagined possibilities. Bmike’s theme of resilience in artworks, “They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds,” mirrors psychologist Ann Masten’s (Citation2001) concept of positive adaptation amidst adversity. Lastly, the author prompts art educators to foster Bmike’s creative spirit, echoing Elliot Eisner’s (Citation2002) philosophy that education should nurture well-rounded, creative, and critical thinkers who can contribute meaningfully to society.

Throughout this issue, the articles have traversed through various spheres of art education—exploring its political dimensions, its potential as a tool for cultural exchange and community engagement, its transformational power, and its role in navigating the digital age. These explorations, grounded in the wisdom and vision of preeminent scholars, offer insightful perspectives at the intersection of art and education. What emerges are telling accounts that address persistent questions about what we believe in, what we value, and how art educational responses to the learning lives of our students are just as powerful and enduring today as they have always been. I would like to leave you with a call to consider the insights presented in this issue of the journal and their implications for our shared field. In line with Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz’s invitation to conduct an Archaeology of Self, let us consider how we, as art educators, can perpetually reflect and adapt our practices in a world in constant flux. In leveraging the transformative power of art, we can aspire to inspire change within individuals, communities, and the spaces we navigate, fostering an environment of growth, creativity, and resilience.

Notes

1 See Women, Work, Washboards: Betye Saar in Her Own Words, a show held in 2018 at the New York Historical Society. More information can be found on their website (https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/women-work-washboards-betye-saar-in-her-own-words). Similarly, Silhouette and Stereotype: Contextualizing Kara Walker’s Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) offers further insight (https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/kara-walker-silhouette-and-stereotype). The New York Historical Society’s website also hosts several useful teacher resources.

2 See Teaching for Artistic Behavior (https://teachingforartisticbehavior.org) by Diane Jaquith and Katherine Douglas.

3 See Studio Thinking (https://www.studiothinking.org/the-framework.html) by Lois Hetland, Jillian Hogan, Diane Jaquith, Kimberly Sheridan, Shirley Veenema, and Ellen Winner.

4 See Harvard Project Zero (https://pz.harvard.edu/projects/multiple-intelligences).

References

- Bates, A. W. (2015). Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for teaching and learning.

- Davis, A. (2016). Freedom is a constant struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement (F. Barat, Ed.). Haymarket Books.

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Minton, Balch.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Kappa Delta Pi.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of Black folk. A. C. McClurg.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1926). Criteria of Negro art. The Crisis, 32, 290–297.

- Eisner, E. W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. Yale University Press.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Continuum.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

- Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. Jossey-Bass.

- Greene, M. (2001). Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education. Teachers College Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

- Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

- Rolling, J. H. (2010). A paradigm analysis of arts-based research and implications for education. Studies in Art Education, 51(2), 102–114.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole & S. Scribner, Eds.). Harvard University Press.

- Zander, M. J. (2007). Tell me a story: The power of narrative in the practice of teaching art. Studies in Art Education, 48(2), 189–203.