ABSTRACT

Previous studies suggest that small rural schools experience a range of challenges relating to their size, financial difficulties and geographical isolation, as well as potential opportunities relating to their position within their communities. In Northern Ireland, these schools are situated within the comparatively rare context of a religiously divided school system. However, research on these schools in this jurisdiction is scarce. The notion of consociationalism is highlighted as central to an understanding of the prevailing schooling system and the peace process in Northern Ireland as a post-conflict society. Set against this backdrop, the paper reports on a survey of principals of small rural schools in Northern Ireland; the challenges they face and their engagement with the communities they serve. The findings reveal how these small rural primary schools, while encountering many similar challenges to such schools globally, continue to play a central consociational role in serving their respective divided communities. Their relationship with the Church is seen as particularly important. The findings raise important broader questions as to the extent to which the current system of schooling is able to contribute to the building of a more integrated society.

Introduction

More than one-third of the NI population live in rural areas, and over 80% of the land mass is rural (DAERA, Citation2020). Against this backdrop, over half (55%) of all 803 primary schools are rural schools, according to figures provided by the Department of Education for the year 2020/2021. These are schools located in settlements with a population of less than 5,000 and areas of open countryside (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency – NISRA, 2015).

Remarkably, given their prevalence and educational significance and despite numerous research studies focusing on small rural schools in different European countries (see Fargas-Malet and Bagley, Citation2021), there has been virtually no research specifically focused on small rural schools in Northern Ireland. The scarce work in this area includes a policy document paper for the Rural Community Network by Gallagher (Citation2002), a research paper for the NI Assembly (Perry and Love, Citation2013) and a recent briefing research report about duplication of primary school provision (Roulston and Cook, Citation2019). While from this limited research, it appears that schools in Northern Ireland are facing similar issues to those in other countries and jurisdictions, particularly in terms of the risk of closure or amalgamation, the Northern Ireland context is remarkably unique, especially when considering it as a post-conflict society (Gallagher, Citation2002).

Northern Ireland is a society which, in general terms, can be divided along religious ethno-national lines between two main groups: a group displaying an Irish political/cultural identity and a Catholic religious background, who tend to favour the project of a united island of Ireland; and a group with a British political/cultural identity and a Protestant religious background, who support and defend the status quo of Northern Ireland being part of the United Kingdom.Footnote1 This division continues to pervade much of NI life and has historically manifested itself in many ways, including periods of recurrent and sustained violence. The latest most serious and sustained one known as ‘the Troubles’ began in the 1960s and formally ended with the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement in 1998.

In the post-conflict context, rural communities have been relatively under-researched in Northern Ireland, compared to their urban counterparts, which has arguably skewed policy including that pertaining to education (Side, Citation2015). This is despite evidence that the legacy of the conflict still influences notions of fear and mistrust of the ‘other community’ among children and parents living in rural areas (Maguire and Shirlow, Citation2004). Shared space in rural areas is likely to be less available than in urban contexts (with a lack of shopping areas and parks), and demarcated social networks are more evident with separate economic, religious, social, political and sporting structures side by side in a small geographical area (Maguire and Shirlow, Citation2004).

Consequently, a study focusing on the links and relationship between small rural schools and their communities in Northern Ireland is important and long overdue. In order to fill this gap, in Spring 2021, as the initial stage of a larger small school rural community study, we conducted a survey of principals of small rural schools in Northern Ireland. In this article, we report on the findings focusing on two main themes: the challenges these schools face; and the ways they engage with parents and the segregated communities they serve. Prior to that, we concisely examine the international literature on small rural schools, provide an overview of the Northern Ireland context, and introduce the theoretical concept of consociationalism (Lijphart, Citation1969); the political settlement including education which underpins peace and the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement 1998. The article then outlines the survey method before moving on to present the findings.

Rural Schools and Small Schools

Globally, education systems and educational policies are often created and conceptualised using an urban model of schooling (Bagley and Hillyard, Citation2019; Sigsworth and Solstad, Citation2005; Wildy and Clarke, Citation2012). Rural schools are often viewed negatively because of the challenges they face due to their geographical isolation and small size (with declining student and staff numbers) (Beach and Vigo Arrazola, Citation2020). Conversely, rural schools have also been found to be able to create identity (Sörlin, Citation2005); develop and maintain social capital (Autti & Hyry-Beihammer, Citation2014; Bagley and Hillyard, Citation2014); play a critical role in the economic life of a community (Halsey, Citation2011); enhance residents’ involvement in community life; serve as a meeting place and ground for network building; and be the ‘social glue’ that keeps the local community together (Kearns et al., Citation2010).

Small schools have been defined in different ways based mostly on the number of pupils enrolled, which ranges from under 70 to under 140 for primary schools (Hargreaves, Citation2009). Other features that have been mentioned are small numbers of staff, small multi-grade classes and principals with significant teaching commitments (Raggl, Citation2015). Small rural schools have featured in research in different countries, including Australia (Clarke and Wildy, Citation2005; Halsey, Citation2011; Starr and White, Citation2008), and a range of European countries (for a recent scoping review, see Fargas-Malet and Bagley, Citation2021). In all these countries, small rural schools are and have been under threat of closure/amalgamation due to a combination of factors, including the marketisation of education and rationalisation of services coupled with the decrease in student numbers (as a result of rural population decline), difficulties in attracting and retaining staff (including principals), and dwindling resources and lack of funding (Bagley and Hillyard, Citation2019; Kovács, Citation2012; Sigsworth and Solstad, Citation2005; Starr and White, Citation2008). Other challenges these schools are facing are ‘staff’s intense (and often unmanageable) workload (including teaching principals having a double job)’; ‘professional isolation of teachers and principals; inadequate infrastructure; challenges in delivering a wide-ranging curriculum; and pedagogical challenges of multi-grade teaching’ (Fargas-Malet and Bagley, Citation2021, p. 18).

Small Rural Schools in Northern Ireland

The context of rural schools in Northern Ireland is particular to the region. There has always been a significant number of small schools. In fact, in 1964, there were as many as over 450 schools with between 26 and 50 pupils, although this number has declined rapidly, and by the early 1990s, there were less than 150 schools with such number of pupils (Gallagher, Citation2002). In 2020/21, 40% of all rural primary schools in Northern Ireland have less than 100 pupils enrolled (n = 178). The abundance of small schools can be partly ascribed to the rural character of the region, a multi-sector and segregated school system, a selective system of education, and a period of demographic decline (Gallagher, Citation2002; Roulston and Cook, Citation2019, Citation2021). In fact, a considerable number of small rural schools are side by side (often only yards apart) serving two communities, with a significant proportion having less than 105 pupils (Roulston and Cook, Citation2019, Citation2021).

However, despite their relevance, small rural schools in NI have historically been viewed as less desirable than their larger urban counterparts, and they have been treated less favourably in the policy arena, as they continue to face a risk of closure or amalgamation. Despite a lack of evidence in this regard, small rural schools have been perceived as being more costly and as having worse academic outcomes than larger schools (Gallagher, Citation2002), with multi-grade teaching (or composite classes) seen as contributing to poorer standards and outcomes. For instance, in 2016, the Minister for Education stated that, by the end of the planning period, he expected actions to address ‘the issue of primary pupils being taught in a composite class of more than two year groups’ (Perry et al., Citation2017).

Just like in other countries, rural schools in Northern Ireland have appeared to be significantly more likely to experience enrolment, financial and educational challenges than their urban counterparts at both primary and post-primary levelFootnote2 (as shown by data from the school viability audits) (Perry and Love, Citation2013). Issues affecting rural schools include provision of a broad curriculum at post-primary, staff opportunities for professional development, difficulties in recruiting teachers and principals, and the threat of closure on the grounds of financial sustainability (ibid). In order to save money and avoid duplication, there have been calls for small schools (which would be close to other schools) to merge and become integrated schools instead (Roulston and Cook, Citation2019, Citation2021).However, on the other hand, pupils in rural schools in NI have been found to perform significantly better (in the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2016) than their urban counterparts, even when pupil characteristics (including eligibility for free school meals and social deprivation as measured in the Super Output Areas) are taken into account (Buzinin and Durbin, Citation2020). In addition, a range of potential advantages of small rural schools have been identified, including improved pedagogical engagement due to smaller staff teams and better school-community relations (Roulston and Cook, Citation2019). Potential implications of closing rural schools have also been identified for finance, transportation and the community (Perry and Love, Citation2013). Indeed, young people living in remote areas with no local school have been found to be disadvantaged in education (unable to reach school when there is ice and snow in winter) and be more socially isolated, e.g. unable to access after-school activities (as there is no bus to leave them home after) (EA, Citation2019). However, crucial to any understanding of schooling in Northern Ireland is the political and religiously segregated system in which it is situated.

Consociationalism and a Divided Schooling System

Following the 1921 partition of the island of Ireland into two territories (the unionist, Protestant-majority north, i.e. Northern Ireland, and the nationalist, Catholic-majority south, i.e. the Republic of Ireland), a denominationally divided dual system of schooling emerged in Northern Ireland; the Catholic and Protestant churches opposing the Ministry of Education’s goal of a state-controlled public and secular education system (Bagley, Citation2019). Today, the schooling system, for the most part, still remains religiously self-segregated (Armstrong, Citation2017), with pupils from the two major groupings mainly ‘choosing’ two different types of schools. School types differ on governance, ownership and funding arrangements. Most pupils from a Protestant community background attend Controlled (de facto state) schools (in which the Protestant churches have a formal role), and most pupils from a Catholic community background attend Voluntary Maintained schools, owned by the Catholic church. Both Controlled and Maintained schools are under the management of the schools’ Board of Governors, with a proportion of their membership being drawn from the local clergy of either Protestant or Catholic churches or their nominees. In 2020/21, these schools make up 87% of all primary and post-primary schools. Following cessation of the Troubles in 1998, it was incumbent on those reaching an agreement to accommodate in some way these societal and educational divisions.

Consequently, the subsequent Good Friday/Belfast Agreement (1998) is a political agreement based on a consociationalist model of democracy, resulting in the establishment of a Northern Ireland Assembly and ‘power-sharing’ Executive. The Agreement was established on the ‘institutional assumption of two communities separate but equal living in peaceful coexistence’ (Fontana, Citation2017, p. 86). A political consociation is ‘a state or region within which two or more cultural or national communities peaceably co-exist with none being institutionally superior to the others and in which the relevant communities cooperate politically through self-government and shared government’ (O’Leary & McGarry, Citation1996). Consociationalism (Lijphart, Citation1969) is understood as a solution for democracies at risk because of social segmentation. Another important aspect of consociationalism is the right for divided communities to be able to ‘establish and administer their own autonomous schools, fully supported by public funds’ (Lijphart, Citation2008, p. 76). Thus, education systems in consociationalist states like Northern Ireland are usually characterised by a diversity of state-funded schools catering for children with different religious ethno-national identities (Bagley, Citation2019). The argument is that if seen as ‘legitimate’ and equal (including in terms of funding), then ‘separate schools may contribute to peace by enhancing feelings of citizenship and stimulating loyalty to a state that reflects and values their cultural group’ (Fontana, Citation2017, p. 228).

In Northern Ireland, the educational status quo in consociational terms is seen as sustaining the integrity of ethnic religious and national groups upon which a stable consociation rests, thereby contributing to political stability and peace. However, in a consociationalist democracy, this separated system is viewed as temporary, and integration is the ultimate goal (McCrudden and O’Leary, Citation2013). Indeed, the Good Friday Agreement does call for the promotion of ‘initiatives to facilitate and encourage integrated education’, inferring implicitly that long-term political stability needs to see a move away from segregation. At this moment in time, after over two decades since the agreement, this ultimate goal is nowhere near to being achieved. There is only a small number of integrated schools (45 out of 803 primaries), which are attended by children and staff from Catholic and Protestant traditions, as well as those of other faiths. The first integrated school, Lagan College, opened in 1981 in the outskirts of Belfast, and it was established by a group of Protestant and Catholic parents. Between 1985 and 1989, 10 other integrated schools were established supported by parental fundraising, trusts and foundations. Further legislation in 1986 provided for existing schools to seek Controlled Integrated status, but this provision was not significantly used before the 1989 Order. There are two types of integrated schools. Grant-maintained integrated schools are self-governing schools with integrated education status, owned and managed by the Boards of Governors, supported by the Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education (NICIE) and funded directly by the Department of Education. Controlled integrated schools, which are Controlled schools that acquired integrated status, are managed by the EA.

At the time of writing, only 7% of pupils attend integrated schools, while the rest attend schools that are largely separated along the traditional Irish/Catholic-British/Protestant lines. Even the initial teacher education system reflects the divided schooling system it serves, as the two largest providers preparing students for primary teaching are markedly segregated, with one having a Catholic ethos and being predominantly chosen by Catholic students (i.e. St Mary’s), and the other being non-denominational and predominantly chosen by Protestant students (i.e. Stranmillis) (Bagley, Citation2019). This partly explains the fact that only 2% of teachers in Catholic Maintained primary schools are from a Protestant background and only 7% of teachers in Controlled schools are from a Catholic background (Milliken, Citation2019).

Thus, despite the existence of policy texts favouring integration and growing public support and parental preference for integrated schools (as shown by public opinion survey findings – with 71% of people in NI believing that integrated education should be the norm – IEF, Citation2021), integrated education has not materialised as much as some would have expected, with the sector’s expansion stalling by the 2000s (Gallagher, Citation2021) and enrolment at Integrated schools not significantly changing (Donnelly et al., Citation2021). In part, this is because influential policy actors such as the Catholic church (Gardner, Citation2016) and the two largest political parties in the NI Assembly and Power Sharing Executive (i.e the ‘Protestant’/Unionist Democratic Unionist Party and the ‘Catholic’/Nationalist Sinn FéinFootnote3) have historically opposed (rather than supported) integrated education (Hansson and Roulston, Citation2021). Without the support from these powerful social and political actors, the number of integrated schools has remained small. However, in March 2022, despite an attempt by the DUP to block it and opposition by the churches and some education sectors, the Northern Ireland Assembly passed the Integrated Education Bill, which places a statutory duty on the Department of Education to provide further support to the integrated schools sector. Only time will tell to what extent this new legislation will make any difference to the integration of the school system.

In contrast to integrated education, however, Shared Education programmes have been more widely embraced, receiving considerable political backing from many political actors (Hansson and Roulston, Citation2021). Through Shared Education, pupils continue to attend their own schools but participate in joint classes and activities with pupils from other types of schools. The first Shared Education programme, the Sharing Education Programme (SEP), was managed by Queen’s University and funded by an international charity (i.e. Atlantic Philanthropies) originally for 3 years (SEP1, 2007–2010). The Shared Education Act (NI) 2016 represented a step forward in embedding sharing within the Northern Ireland education system. However, according to the UK Children’s Commissioners (Citation2015), concerns have been raised about the quality of some shared education initiatives, the opportunity for all pupils to take part and the sustainability of shared education. Indeed, despite general evidence of positive outcomes of Shared Education (Borooah and Knox, Citation2013; Hughes et al., Citation2012; Loader and Hughes, Citation2017a), some studies have shown that it does not necessarily lead to more meaningful cross-community contact between pupils from the two backgrounds (Loader and Hughes, Citation2017b; Roulston and Hansson, Citation2021). Moreover, Shared Education does not appear to address reconciliation and does little/nothing to systematically change the structure of education provision in NI (Roulston and Hansson, Citation2021).

The Northern Ireland ‘small School Rural Community Study’

The ‘Small School Rural Community Study’ aims to explore the interrelationship between small rural schools in Northern Ireland and the rural communities they serve. The BAIN review (2006), which was commissioned by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, established that primary schools in rural areas should have at least 105 pupils enrolled. The Review concluded that there should be fewer, larger schools, which are educationally sustainable and maximise the potential of their resources. Subsequently, the Department of Education’s sustainable school policy recommended 105 as the minimum enrolment threshold for primary schools in rural areas (DoE, Citation2009). Within the Northern Ireland context, thus, it makes sense to define small rural primary schools as those schools located in rural areas with less than 105 pupils enrolled. In 2020/21, 43% of all rural schools were small if this definition is applied.

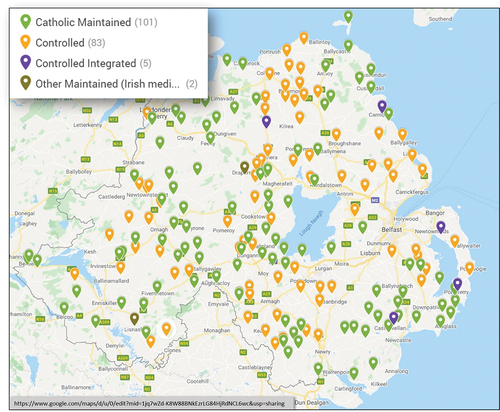

Indeed, in the school year 2020/21, there were 191 schools that met these criteria, scattered all over Northern Ireland (see ). Most of these 191 schools were either Controlled (n = 83; 43%) or Catholic Grant-Maintained (n = 101; 53%) schools. In a recent study, 69 isolated pairs of small rural schools, one Controlled and one Maintained, within a mile of each other, were identified (Roulston and Hansson, Citation2021). However, many of these 184 schools (i.e. 83 Controlled and 101 Maintained small rural schools) were instead located near other small schools of the same type, rather than only beside one of the other types (see ). The remaining seven schools were either Controlled Integrated (n = 5) or Irish-Medium schools (n = 2).

No significant differences were observed between the largest two types of schools in terms of social deprivation indicators (i.e. the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Super Output Area (SOA) quintiles where the schools were located; and the percentage of children entitled to Free School Meals). Most of the schools were situated in the middle SOA quintiles (2, 3 and 4 rather than 1 and 5), which means that only a few schools were in the most and least deprived areas (9% and 4% respectively). The average proportion of children entitled to free school meals was 23%, although in many schools, this information was not available due to confidentiality concerns as there were only a small number of pupils enrolled.

The Survey of Principals

As part of the ‘Small School Rural Community Study’, a survey of principals of small rural schools in Northern Ireland was conducted between April and end of June 2021. Principals play a crucial role in the relationship between the school and the community, as they are often seen as the ‘public face’ of the school. In addition, they were deemed as potential key informants on the school’s characteristics, challenges and community engagement. An invitation to participate in the online survey was emailed to the principals of 201 rural schools. As mentioned earlier, the schools were selected on the basis that they were considered rural (based on the NISRA’s definition) and had 105 pupils or less enrolled. However, the selection was initially done based on the data for the 2019/20 school year, when there were 198 schools that fitted those criteria. Two had closed down at the end of that school year, leaving 196 schools. The data from the 2020/21 school year became available, making another five schools eligible, and ten of the already selected grew their number of enrolled pupils, but they were not removed from the survey. All the 201 schools included had less than 116 pupils.

The online questionnaire included closed questions regarding general information (e.g. school’s age, principal’s years’ experience as principal at that school or whether the principal was a teaching principal); technology the school uses to communicate with families; key challenges; relationship between parents/families and the school (e.g. ways the principal/school engaged with parents/families prior to the pandemic); relationship between the community and the school (e.g. most influential institutions/organisations of the community the school serves or ways the principal/school engaged with the local community and its main institutions); relationship between other schools and the school (e.g. things the school does with other schools prior to the pandemic); and relationship between policy organisations and the school (e.g. how supportive each organisation has been). In addition, the questionnaire had an open-ended question where they could leave any comments regarding the relationship between the school and the community – 38 principals provided a comment.

In total, 91 responses were received although five of them were incomplete. Thus, despite the challenges of conducting research during a global pandemic and online surveys typically having a lower response rate than face-to-face surveys, a good response rate (i.e. 43% for completed responses) (Dillman et al., Citation2014) was achieved by following a range of strategies, including following up non-respondents by email and phone calls. The schools of the 86 principals that completed the survey are described in below, in terms of school type and size, and compared to the whole population of schools that were invited to take part. As shown in these tables, based on school type and size, representativeness was maintained in the sample that took part.

TABLE 1. School type (%)

TABLE 2. School size 2020/21 (%)

Ethical approval for the survey was granted by the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work in Queen’s University Belfast. Principals were emailed an information sheet about the study, the link to the online survey, an anonymous identifier to enter into the online survey and had to tick a consent form at the start of the survey.

Findings

The findings of the survey are presented here within two main themes. Firstly, we focus on the challenges that these small schools face according to their principals. Secondly, we reveal the self-segregated nature of these schools and the communities they serve. This second part is divided into three sub-sections based on the questions asked in the survey, i.e. the characterisation of the area where the schools are located; the main institutions of the community within which the schools are situated; and how the schools engage with their communities.

Challenges

Principals were asked to select a maximum of five key challenges their schools were facing. Principals could choose from a range of potential challenges, including those found in the literature (e.g. pressure/threat of potential closure or financial pressures) and others that many schools, not necessarily rural, appear to be facing (e.g. rising mental health difficulties for pupils and staff). An open-ended ‘other’ option was also included, where principals could write other challenges not mentioned. The main challenges selected by principals were mostly those found in other research in different European countries. Out of 90 principals that answered this multiple-choice question, most principals selected financial pressures and lack of funding (74) and staff’s intense workloads (72) as key challenges they faced. The other most selected challenges were increasing numbers of pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (47); declining pupil numbers (45); pressure or threat of potential closure (28); lack of staff opportunities for professional development (22); competition from other schools (22); and rising mental health difficulties for pupils and staff (18). However, in contrast with other studies, difficulties in staff recruitment and retention were barely ever selected as current challenges (just two principals in Controlled schools did). In addition, 17 principals did write in the ‘Others’ open-ended box, although some of the responses referred to challenges already identified, particularly in terms of financial pressures. Two responses were to explain that the school was due to close at the end of that school year. Other challenges mentioned were added pressures in relation to the COVID pandemic (n = 3); ‘difficulty accessing support services’; ‘pressure over transfer tests and results’; and ‘Geography – school at bottom of peninsula so catchment area is only one way’.

TABLE 3. Ways the principal and the school engaged with the local community and its main institutions/organisations prior to the pandemic

There were only three substantial differences between principals of the different school types. While only 23% of principals in Catholic Maintained schools (n = 10) selected threat of closure, 40% (n = 17) of principals in Controlled schools did. While only 19% (n = 8) of principals in Controlled schools selected a lack of opportunities for professional development, 32% (n = 14) of principals in Catholic Maintained schools did. Finally, while only 16% (n = 7) of principals in Catholic Maintained schools identified competition from other schools, 29% (n = 12) of Controlled schools did.

Other differences identified regarding challenges were related to school size, with declining pupil numbers, pressure to close and lack of staff opportunities for professional development appearing to be more of a problem the smaller the school (see ). On the other hand, competition from other schools and increasing numbers of pupils with SEN appeared to be more of an issue in larger schools.

TABLE 4. School challenges by school size

Some of the comments written by principals explained these main challenges they encountered and illustrated how they were often interconnected:

… Our school, that twenty-thirty years ago would have had 7 straight classes, now is struggling with 4 composite classes. Our parents ARE supportive of our school but small numbers means we are struggling to survive in this community. … . (Principal, Catholic Maintained school)

Unfortunately, the threat of closure is ever present and this has stopped some families enrolling at the school thus resulting in a fall in our enrolment numbers which are hard to recover from. Our physical site also needs a lot of investment but this does fail to materialise because of question marks over our future which results in the local community not having faith that our school will remain open and so they choose to travel further away. (Principal, Controlled school)

To sum up, regardless of school type and size, the main challenges that the principals highlighted (within the list provided) were financial pressures and staff’s workload, and many of these appeared interrelated.

Schools Serving Divided Communities

Most of the schools that took part in our survey were either Controlled (n = 42) or Catholic Maintained schools (n = 45). Only three integrated schools took part (of five in the whole population of 201).

Divided Communities

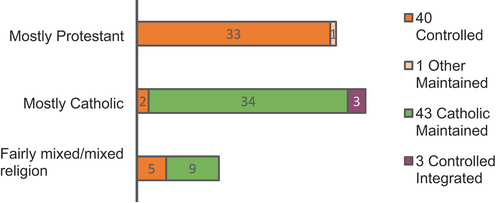

Principals were asked to describe the communities their schools served as either mostly Catholic, mostly Protestant, fairly mixed and mixed. The majority of principals described the communities their schools served as either mostly Catholic or mostly Protestant. Only 16% described the communities as fairly mixed or mixed; and these were five principals of Controlled schools and nine principals of Maintained schools. As expected, the description of the community depended on school type (see ). Thus, the majority of principals of Controlled schools described their communities as mostly Protestant while the majority of principals of Catholic Maintained schools described their communities as mostly Catholic. Surprisingly, however, the three principals of Integrated schools described their communities as mostly Catholic.

Influential Community Institutions

Principals were also asked to pinpoint the most influential institutions and organisations of the community their schools served. The institution that was most identified was the church/chapel/parish, which was selected by 90% of the 87 principals that answered this question. This reflects the enormous importance of religious institutions in these rural communities. There was very little difference regarding type of school, so this was applicable to the two sides of the sectarian divide.

The second most influential organisation was deemed to be the school/s, which was selected by 80% of the principals. Thus, the majority of principals saw their school as a key institution in the community. This was reflected in many of the open-ended comments they wrote at the end of the questionnaire:

This school is very much at the heart of the community; our school is literally situated right in the centre of the village with the community able to see into the grounds on all sides. If there is something happening everyone will see it. We have built and maintain a familial relationship with our parents and the community. We are involved on a social level with events. Any events that are happening we are involved. WE are approachable for the community. (Principal, Controlled school)

Our school is the heart of the rural community. Our families often have no other outlet or community-based organisation to support them. People come to live in the village because of our school. We offer support for parents and work closely with community groups to offer social events. (…) (Principal, Catholic Maintained school)

We have very strong links with our community and I have been told recently that the school is valued and appreciated- especially the support and remote learning which was given to pupils and parents during Covid. The school is the heart of the community, as is the church and the Gaelic Athletic Club. (principal, Catholic Maintained school)

Just over half of principals (n = 46) identified a sporting association as one of the most influential, but most of these were principals of Catholic Maintained schools (39 out of 43). This is because Gaelic Athletic clubs (GAC) are very influential and popular in Catholic rural areas in Northern Ireland. The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) is Ireland’s largest sporting organisation, and it promotes Gaelic games. There are six different games in the family of Gaelic Games (i.e. Hurling, Gaelic football, Handball, Rounders, Camogie and Ladies Football). This is further reinforced by the fact that all but one of the principals who described the community their school served as mostly Catholic (38 out of 39) selected a sports organisation as a key institution/organisation, while only one principal who described the community as mostly Protestant did. Similar to education, ‘sport has been part of the system of division in which people’s religious community background heavily influences’ people’s lives (e.g. where they live, go to school, and what sports they play and watch) (Mitchell et al., Citation2021, p. 464). In Protestant communities, rugby, football or cricket clubs would also be popular, but not as dominant and common as GAA would be in Catholic communities. One of the principals saw this big influence as a potential problem:

GAA seems to be very important to the local community, however, I would like a broader approach to sports for those children who do not like GAA or are part of the local club. The children feel like if they do not play GAA, then they are not part of the community. I am trying to ensure that we provide a curriculum that suits everyone, however, budgets are tight, so this is not always possible. (Principal, Catholic Maintained school)

Other institutions and organisations were selected by fewer principals. Other influential institutions were community voluntary groups (n = 13), youth clubs (n = 9) or a cultural organization (n = 5). In addition, 11 principals selected the ‘Other’ box. In that option, principals wrote bands (n = 2), traditional music group (n = 2), community association, local business, Orange Order,Footnote4 Village HallFootnote5 Committee and Young Farmers’ club.

Ways Schools Engage with Their Communities

Principals were also asked to identify the ways the school and they as principals engaged with the community and their institutions. A number of ways were presented in the questionnaire, and principals selected those that applied, with the option to specify other ways not mentioned. As shown in , the majority of principals pinpointed the following ways (in order of most ticked): Church/religious leaders coming regularly to the school to visit pupils and teachers; community leaders being in the Board of Governors (BoG) of the school; maintaining social media accounts; after-school activities organised by community/sporting/religious organisations taking in place in school grounds or being advertised by the school; and pupils being actively encouraged in the school to get involved with particular community organisations. In the ‘Other’ box, principals specified ‘Christmas or summer fairs’, and ‘involving children in community events, e.g. cross community carol service, visiting two local nursing homes to sing at Christmas and deliver gifts and handmade cards’.

What was evident in the answers to that question and to the open comment box was the key role of the churches within the schools, but also how schools shared resources and utilised others from the community. As the following comments reveal:

Our school is an asset to the community it serves. It acts as a focal point for a wide range of community organisations. (Principal, Controlled school)

The school is a central part of our rural community. Enabling local groups to access our facilities assists local groups and clubs to exist. (Principal, Catholic Maintained school)

We depend on the community. We have a good relationship with them. The secretary of the school is the secretary of the community association. The community association are looking to do a historical project and asking the children to provide photos for that. (Principal, Controlled school)

Significantly, most principals indicated that their schools were engaged in cross-community events (other than Shared Education) prior to the start of the pandemic, with 54% engaging quarterly or more often and a further 19% engaging at least once a year. Only 22% (n = 19) (i.e. 17% of Controlled schools and 26% of Catholic Maintained schools) indicated that they did not. In addition, most principals who answered this question stated that their school had participated in Shared Education programmes prior to the pandemic, with three-quarters stating that they had recently done so (including 78% of Controlled school principals and 70% of Catholic Maintained school principals) and a further three schools having participated in the past. Only 20% (n = 17) had never done so. As the following quotes reveal:

We are actually one of few schools with a cross-border Shared Education programme. We are teamed with two schools in Donegal. (Principal, Controlled school)

The rural school has always had very good links with its neighbouring maintained school and has also developed new links with another small rural school through Shared Education. Each of these links has raised the profile and cemented the place of the small school in the community and the governors and parents are particularly pleased with how the school joins together with these other schools. (Principal, Controlled school)

Seemingly, while continuing to be schools strongly embedded within their religious ethno-national communities, principals indicated that their schools made efforts to engage the ‘other’ community. A process occurring either through engagement in cross-community events or a Shared Education-based initiative. Unfortunately, the quantitative data are unable to report the extent to which such initiatives are helping to bring the two segregated communities closer together.

Concluding Discussion

In this paper, we have attempted to contribute to the relatively little amount of published research literature pertaining to small rural primary schools in Northern Ireland. Subsequently, and despite the acknowledged limitations of the survey, we have been able to uncover two important findings. Firstly, in terms of challenges, many of those faced by small rural primary schools in Northern Ireland are similar to those found in other parts of Europe and further afield, e.g. financial pressures and lack of funding, staff’s intense workloads and declining pupil numbers (Fargas-Malet and Bagley, Citation2021). In this study, unsurprisingly, the size of schools was also found to be relevant regarding the prevalence of these challenges, e.g. smaller schools faced a bigger threat of closure. However, the survey also found differences from research elsewhere. For example, difficulties in staff recruitment and retention were rarely identified in our study in contrast with other studies (e.g. Hillyard and Bagley, Citation2013; Tsiakkiros and Pashiardis, Citation2002).

Secondly, perhaps particularly significant and salient, given the critical role of education and schooling within Northern Ireland’s peace settlement, i.e. the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement 1998, our survey findings highlighted the central role of small rural schools in serving their respective religiously divided communities. Thus, small rural schools in Northern Ireland were found to be very much embedded within their communities, and rooted within a place (e.g. as one principal writes, ‘literally situated right in the centre of the village’). Importantly, while this is a common theme in other studies (Bagley and Hillyard, Citation2011), Northern Ireland presents a very specific political and socio-cultural context for small rural schools. Rural communities in Northern Ireland are often ethno-national and religiously homogenous, with shared interests, norms and identities, expressed through cultural symbols, rituals and traditions. As Shortall and Shucksmith (Citation2001) observe, communities in rural Northern Ireland often live separate and distinct lives with two types of schools, two types of youth clubs, two churches and different religious events/practices/rituals, two community groups and so on. Shared spaces are scarce in rural areas, and places are tied up with politics and identity, where people do not use the one that does not ‘belong’ to their own community (Shortall and Shucksmith, Citation2001). In addition, a related and key distinctive feature we found of small rural schools in Northern Ireland was the importance of religion and the churches. This was apparent for all types of schools (especially Controlled and Catholic Maintained schools) with most schools having religious leaders (e.g. priests and pastors) in their Board of Governors who visited the school regularly. Although not exclusive of rural communities and small rural schools in the region, we have used the concept of consociationalism to make sense of the context in which small rural schools in Northern Ireland exist, as small rural schools have barely featured in research here.

In line with consociational principles, the 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement did not challenge the existence of parallel and separate school sectors but gave education the dual function of preserving separate identities while encouraging mutual understanding and tolerance (Fontana, Citation2017). As a result, as Fontana (Citation2017) claims, the Northern Ireland education system is based on ‘civic minimalism’ in which, through a process of parental choice, parents tend to choose schools with an existing profile and ethos similar to their own. In this way, ‘schools tend to cater for uniform student bodies in terms of their income, ethnicity and religion’ (Fontana, Citation2017, p. 228). Although in consociational terms, any potential self-segregation is supposed to be temporary, ‘informal separation based on customs and practice is harder to erode than legally enforced segregation’ (Fontana, Citation2017, p. 228). Indeed, consociationalism is criticised for lacking ‘clarity from its adherents as to how it helps society move from conflict management to transformation’ (Nagle and Clancy, Citation2010, p. 4). In essence, a consociational conundrum is established, in which continued peace relies on the same self-selected divisions it is ultimately intended to resolve. Moreover, in practical terms, the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (1998) affords only very limited reference to future education policy reform, referring only to the need to promote the Irish Language and the need for initiatives to develop integrated education. This has meant that, at the policy level, the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (1998) has had very little impact on the delivery of Education in Northern Ireland. Rather, what it has achieved is to simply consolidate the same segregated education system which was in place prior to the Agreement’s existence. Notwithstanding this possibility, pro-consociationalists would argue that the Agreement still offers the needed socio-political scaffolding and stability, which, over the long term, will diminish religious ethno-national division. As such, in reaching its main goal of conflict resolution, the consociational settlement grants the best opportunity and deepest ‘foundations for peaceful democratisation’ (McCrudden and O’Leary, Citation2013, p. 36). If the price for a managed peace in Northern Ireland is a consociational settlement, this does not disprove the fact that schools (including small rural schools) have an important role to play, including supporting the settlement and peaceful co-existence as well as working towards a more integrated society.

However, in the Northern Ireland context, denominationally separate schools cannot be expected to establish ‘social cohesion as readily as integrated schools where contact is sustained’ (Fontana, Citation2017, p. 229). Indeed, Hughes et al.’s (Citation2007) research has shown how cultural and physical separation in schooling between communities from different religious backgrounds in Northern Ireland could stimulate suspicion and fear towards members of other communities, thus inhibiting the development of mutual understanding and trust. Educationally, as we have signalled in this paper, with the seeming lack of any substantive political desire or policy movement regards the provision of integrated schooling, increasing emphasis was given to the concept of Shared Education; i.e. the building of sustained informal and formal links between schools serving different religious communities. Indeed, our survey findings suggested that many small rural schools make a conscientious effort to engage with the ‘other’ community through Shared Education programmes and cross-community events.

A key question remains as to the effectiveness of such initiatives in fundamentally reconciling deep-seated conflicting religious ethno-national identities, in what remains an institutionally and structurally divided society. The mainly quantitatively derived information we have gathered to date through the survey does not help us address such questions nor tell us much about the (inter)relationship between schools and communities within rural areas. A second phase of our study is ongoing, involving case studies of a number of small rural schools (Catholic, Controlled and Integrated), with such issues explored qualitatively in-depth. Barrett (Citation2015) recognises that communities are contested spaces, in which ‘contradictory dynamics push and pull at each other’ (p.194). In terms of Northern Ireland’s consociational settlement, it remains to be seen if the close relationship between small rural primary schools and the divided communities they serve, while pulling together, are simultaneously (though not necessarily deliberately) still pushing apart. Until more research is undertaken, the broader concern is that as long as the same divisive education systems are used to manage the peace as previously underpinned the ‘Troubles’, then the potential for schools to make an enduring societal difference is limited and the potential for a return to religious ethno-national conflict remains.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 These divisions are generalisations. As such, we acknowledge there will be followers of the Catholic faith who support Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK, and those of the Protestant faith who support the creation of a united Ireland.

2 In Northern Ireland, children go to primary school for seven years between the ages of 4 to 5 (Primary 1) to the ages of 10 to 11 (Primary 7), when they transfer to post-primary school, which goes from Year 8 (age 11 to 12) to Year 14 (age 17 to 18).

3 However, Sinn Féin’s position towards integrated education has shifted in recent years, and they clearly showed their support towards the Integrated Education Bill, now Act.

4 The Orange Order is a Protestant order based in Northern Ireland. Many villages and towns in the region have Orange Halls, where monthly meetings and community events take place and are associated with the Protestant/Unionist communities. The halls often host community groups such as local marching bands or Ulster Scots cultural groups.

5 In many villages in the United Kingdom, village halls are community facilities available to the public in a particular area for community-related activities and events. They are usually run by committees and constitute small charities.

References

- Armstrong, D. (2017) Schooling, the protestant churches and the state in Northern Ireland: a tension resolved, Journal of Beliefs & Values, 38 1, 89–104.10.1080/13617672.2016.1265860

- Autti, O. and Hyry-Beihammer, E. K. (2014) School closures in rural Finnish communities, Journal of Research in Rural Education, 29 1,1–17

- Bagley, C. (2019) Troubles, transformation and tension: education policy, religious segregation and initial teacher education in Northern Ireland,Revista de Curriculum y Formacion del Profesorado, 23, 4. https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/197266448/77083_247243_1_PB.pdf

- Bagley, C. and Hillyard, S. (2011) Village schools in England: at the heart of their community?, Australian Journal of Education, 55 1, 37–49.10.1177/000494411105500105

- Bagley, C. and Hillyard, S. (2014) Rural schools, social capital and the big society: a theoretical and empirical exposition, British Educational Research Journal, 40 1, 63–78.10.1002/berj.3026

- Bagley, C. and Hillyard, S. (2019) In the field with two rural primary school head teachers in England, Journal of Educational Administration and History, 51 3, 273–289.10.1080/00220620.2019.1623763

- Barrett, G. (2015) Deconstructing community, Sociologia Ruralis, 55 2,182–204

- Beach, D. and Vigo Arrazola, M. B. (2020) Community and the education market: a cross-national comparative analysis of ethnographies of education inclusion and involvement in rural schools in Spain and Sweden, Journal of Rural Studies, 77, 199–207.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.05.007

- Borooah, V. K. and Knox, C. (2013) The contribution of ‘shared education’ to Catholic–Protestant reconciliation in Northern Ireland: a third way?, British Educational Research Journal, 39 5, 925–946.10.1002/berj.3017

- Buzinin, R. and Durbin, B. (2020) PIRLS 2016 further analysis: Urban and rural schools in Northern Ireland. Slough, Berkshire: NFER. Available at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/4173/pirls_2016_further_analysis_urban_and_rural_schools_in_northern_ireland.pdf (accessed 05 December 2021).

- Clarke, S. and Wildy, H. (2005) Leading the small rural school: the case of the novice principal, Leading and Managing, 11 1,43–56

- DAERA (2020) Key Rural Issues. Belfast: DAERA. Available at: https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/daera/Key%20Rural%20Issues%202020%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed 12 December 2021).

- Dillman, D., Smyth, J. D. and Christian, L. M. (2014) Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method 4th New York: Wiley & Sons

- DoE, (2009) Schools for the Future: A Policy for Sustainable Schools (Belfast, Department of Education). Available at: https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/publications/schools-future-policy-sustainable-schools

- Donnelly, C., McAuley, C. and Lundy, L. (2021) Managerialism and human rights in a post-conflict society: challenges for educational leaders in Northern Ireland, School Leadership & Management, 41 1–2, 117–131.10.1080/13632434.2020.1780423

- EA (2019) Youth service research needs of rural young people. Belfast: Education Authority. Available at: https://www.eani.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/Youth%20Service%20Research%20-%20Needs%20of%20Rural%20Young%20People.pdf (accessed 05 December 2020).

- Fargas-Malet, M. and Bagley, C. (2021) Is small beautiful? A scoping review of 21st-century research on small rural schools in Europe, European Educational Research Journal. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/14749041211022202 (accessed 07 June 2021).

- Fontana, G. (2017). Education Policy and Power-Sharing in Post-Conflict Societies: Lebanon, Northern Ireland, and Macedonia. Birmingham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gallagher, T. (2002) Small Rural Schools in Northern Ireland. A Policy Discussion Document Prepared for the Rural Community Network Belfast.Rural Community Network)

- Gallagher, T. (2021) Governance and leadership in education policy making and school development in a divided society, School Leadership & Management, 41 1–2, 132–151.10.1080/13632434.2021.1887116

- Gardner, J. (2016) Education in Northern Ireland since the Good Friday Agreement: kabuki theatre meets danse macabre, Oxford Review of Education, 42 3, 346–361.10.1080/03054985.2016.1184869

- Halsey, R. J. (2011) Small schools, big future, Australian Journal of Education, 55 1, 5–13.10.1177/000494411105500102

- Hansson, U. and Roulston, S. (2021) Integrated and shared education: sinn Féin, the Democratic Unionist Party and educational change in Northern Ireland, Policy Futures in Education, 19 6, 730–746.10.1177/1478210320965060

- Hargreaves, L. M. (2009) Respect and responsibility: review of research on small rural schools in England, International Journal of Educational Research, 48 2, 117–128.10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.004

- Hillyard, S. and Bagley, C. (2013) ‘The fieldworker not in the head’s office’: an empirical exploration of the role of an English rural primary school within its village, Social & Cultural Geography, 14 4, 410.10.1080/14649365.2013.779743

- Hughes, J., Campbell, A., Hewstone, M. and Cairns, E. (2007) Segregation in Northern Ireland - Implications for Community Relations Policy. Policy Studies, 28, 35–53.

- Hughes, J., Lolliot, S., Hewstone, M., Schmid, K. and Carlisle, K. (2012) Sharing classes between separate schools: a mechanism for improving inter-group relations in Northern Ireland?, Policy Futures in Education, 10 5, 528–539.10.2304/pfie.2012.10.5.528

- IEF (2021). Northern Ireland Attitudinal Poll [Summary Report June 2021] (Belfast, The Integrated Education Fund). Available at: https://view.publitas.com/integrated-education-fund/northern-Ireland-attitudinal-poll/page/1

- Kearns, R. A., Lewis, N., McCreanor, T. and Witten, K. (2010) School closures as breaches in the fabric of rural welfare: community perspectives from New Zealand. P. Milbourne (Ed.) Welfare Reform in Rural Places: Comparative Perspectives Bingley,Emerald Group Publishing Limited 219–236

- Kovács, K. (2012) Rescuing a small village school in the context of rural change in Hungary, Journal of Rural Studies, 28 2, 108–117.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.01.020

- Lijphart, A. (1969) Consociational democracy, World Politics, 21 2, 207–225.10.2307/2009820

- Lijphart, A. (2008) Thinking about Democracy: Power Sharing and Majority Rule in Theory and Practice Abingdon.Routledge)

- Loader, R. and Hughes, J. (2017a) Balancing cultural diversity and social cohesion in education: the potential of shared education in divided contexts, British Journal of Educational Studies, 65 1, 3–25.10.1080/00071005.2016.1254156

- Loader, R. and Hughes, J. (2017b) Joining together or pushing apart? Building relationships and exploring difference through shared education in Northern Ireland, Cambridge Journal of Education, 47 1, 117–134.10.1080/0305764X.2015.1125448

- Maguire, S. and Shirlow, P. (2004) Shaping childhood risk in post‐conflict rural Northern Ireland. Children’s Geographies, 2 (1), 69–82.

- McCrudden, C. and O’Leary, B. (2013) Courts and Consociations: Human Rights versus power-sharing New York.Oxford University Press)

- Milliken, M. (2019) Employment mobility of teachers and the FETO exception. Coleraine: Ulster University. Available at: https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/ws/files/77261808/TEUU_Report_01_Feto_Final.pdf (accessed 10 October 2021).

- Mitchell, D., Somerville, I., Hargie, O. and Simms, V. (2021) Can sport build peace after conflict? Public attitudes in transitional Northern Ireland, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45 5, 464–483.10.1177/0193723520958346

- Nagle, J. and Clancy, M. A. C. (2010) Shared society or benign apartheid?: understanding peace-building in divided societies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Leary, B. and McGarry, J. (1996) The politics of antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland. London: Athlone Press.

- Perry, C. and Love, B. (2013) Rural schools. Belfast: Northern Ireland Assembly. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2013/education/2713.pdf (accessed 16 May 2020).

- Perry, C., Love, B. and McKay, K. (2017) Composite classes. Belfast: Northern Ireland Assembly. http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/29219/1/0517.pdf (accessed 16 May 2020).

- Raggl, A. (2015) Teaching and learning in small rural primary schools in Austria and Switzerland—Opportunities and challenges from teachers’ and students’ perspectives, International Journal of Educational Research, 74, 127–135.10.1016/j.ijer.2015.09.007

- Roulston, S. and Cook, S. (2019) Isolated together: pairs of primary schools duplicating provision. Coleraine: Ulster University. https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/77906204/TEUU_Report_03_Isolated_Pairs.pdf (accessed 17 May 2020).

- Roulston, S. and Cook, S. (2021) Isolated together: proximal pairs of primary schools duplicating provision in Northern Ireland, British Journal of Educational Studies, 69 2, 155–174.10.1080/00071005.2020.1799933

- Roulston, S. and Hansson, U. (2021) Kicking the can down the road? Educational solutions to the challenges of divided societies: a Northern Ireland case study, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42 2,170–183

- Shortall, S. and Shucksmith, M. (2001) Rural development in practice: issues arising in Scotland and Northern Ireland, Community Development Journal, 36 2, 122–133.10.1093/cdj/36.2.122

- Side, K. (2015) Re-Assessing rural conflict: rituals, symbols and commemorations in the Moyle District, Northern Ireland, Journal of Rural and Community Development, 9 4,102–127

- Sigsworth, A. and Solstad, K. J. (2005) Small Rural Schools: A Small Inquiry. Cornwall: Interskola

- Sörlin, I. (2005) Small Rural Schools: a Swedish perspective. A. Sigsworth and K. J. Solstad (Eds) Small Rural Schools: A Small Inquiry. Cornwall: Interskola, 18–23

- Starr, K. and White, S. (2008) The small rural school principalship: key challenges and cross-school responses, Journal of Research in Rural Education, 23 5,1–12

- Tsiakkiros, A. and Pashiardis, P. (2002) The management of small primary schools: the case of Cyprus, Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1 1, 72.10.1076/lpos.1.1.72.5403

- UK Children’s Commissioners (2015) Report of the UK children’s commissioners UN committee on the rights of the child examination of the fifth periodic report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

- Wildy, H. and Clarke, S. (2012) Leading a small remote school: in the face of a culture of acceptance, Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 40 1, 63–74.10.1080/03004279.2012.635057