Abstract

Standard accounts of the concept of ‘modern brand’ consider it to have developed in the late nineteenth century with the second industrial revolution and to have a range of unique characteristics, including a personality of its own and to be protected by law. Modern brands are considered to have succeeded proto brands, which relied essentially on quality and origin for differentiation. To trace this path, standard accounts build strong links between law, brand identity and product differentiation, suggesting that law and brand are ‘symbiotic’. Looking at a country with early, yet relatively weak, trademark law and a poorly structured registration system and focussing on the previously little analysed case of the Brazilian South American Tea industry during the period 1875–1913, this study suggests that we need to consider two other typologies in the evolution of brands: ‘proto legal brands’ and ‘differentiated proto brands’. So doing, this account provides an innovative view of legislation and registration, and their problematic contribution to anti-competitive protectionism.

1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that brands are a central feature of the modern economy, playing multiple, interconnected roles in the construction of marketplaces (Desai & Waller, Citation2010). Brands have existed for over 4,000 years as marks and symbols, conveying information to different stakeholders about the quality of goods or services traded and indicating their origin. The contribution and meaning of brands or marks has, however, evolved over time. The earlier forms of branding, also known as proto brands, essentially aimed to identify the origin (place or person that produced it) of products and provided information to the consumer about their characteristics and quality (Alexander & Doherty, Citation2021; Hopkins, 1905/Citation2018; Moore & Reid, Citation2008; Rogers, Citation1910; Schechter, Citation1925; Wilkins, Citation1992). Modern brands are considered by standard accounts in business history, economics and law to have succeeded proto brands. They relate to names of products or services, designs, logos, words or arrangements of words, distinctive shapes, and symbols or characters which are used to identify products and certify their quality. They have the capacity to translate firms’ marketing strategies, and thereby create differentiating products or services in relation to competitors in the eyes of consumers and also protect their intellectual property through the law (Gardner & Levy, Citation1955). Differentiation strategies relying on branding reduce competition and create monopoly power by raising barriers to entry (Bain, Citation1956; Chamberlin, 1933/Citation1962; Mann, Citation1966). Modern brands rely on a combination of characteristics ranging from product/service performance to non-functional dimensions, thereby creating personalities and imagery for brands which incorporate consumers’ motives, feelings, and attitudes (Aaker, Citation1991; Lopes, Citation2007). The legal protection of modern brands means that their intellectual property cannot be appropriated by others through imitation. This provides brands with the capacity to remain ‘forever young’, as trademark registrations can be renewed eternally, unlike other forms of intellectual property such as patents and copyrights which can only be legally protected for limited time periods (Lopes, Citation2019).

This study unbundles the concept of the modern brand, to provide a thorough analysis of the different roles and meanings brands historically had for business. It addresses the following questions: Drawing on historical evidence, is it possible to find branding practices that do not conform with the existing dichotomy of definitions of ‘proto brand’ and ‘modern brand’? If so, what do these different branding practices entail and how effective are they in the context - period and space - where they take place? Is it possible for brands to grow and thrive in the long-term without unbundling differentiation strategies from legal protection as it is implicit in the concept of the modern brand? To address these questions, the study focuses on the case of the Brazilian South American tea industry and draws on a wide range of original archives, historical court cases, trade press, newspaper adverts, and on trademark registration data for the period from 1875 until 1913 as well as other country and industry statistics.Footnote1 This is a crucial period in the development of the modern brand worldwide (Lopes & Duguid, Citation2010). It is also a period of rapid expansion and economic significance of the Brazilian South American tea industry, also known as Erva Mate (in Portuguese) or Yerba mate (in Spanish). Other names for which this product is also known around the world are Ilex Paraguariensis and Paraguayan tea because Paraguay was the first country to produce and trade this type of tea internationally on an industrial scale.Footnote2 The methodology used is in line with the growing literature that follows the seminal work of Wilkins (Citation1992) on the advantages of studying trademarks to help explain different economic phenomena (Wilkins, Citation1992).

The study is organised in five parts. After the introduction, section 2 defines the concepts of proto brand and modern brand and discusses the evolution of its components of indication of origin, differentiation and protection by law. Section 3 analyses the significance of South American tea in the Brazilian economy from 1875 to 1913 and relates that evolution to the relatively abnormal number of trademark registrations of this product in Brazil during that period. It also discusses the significance of the top South American tea firms in the international trade and long-term development of the industry. Section 4 compares the use of South American tea brands with those of businesses and industries often considered to have adopted modern brands from the late nineteenth century. Based on that evidence, this section also puts forward a framework which illustrates the various roles brands may have in business. Finally, section 5 provides some conclusions arguing that unbundling the concept of the brand allows a better understanding of how brands are used in different periods of time and different institutional environments, and what is their significance in marketplaces over time.

2. The brand as a source differentiation and a barrier to entry

The ‘modern brand’ has two distinctive characteristics when compared to the ‘proto brand’. Firstly, it differentiates products and services in a deeper way, beyond providing information about their quality, and is part of firms’ marketing strategy aimed at creating a barrier to entry to competitors. Secondly, it is protected by law, allowing the enforcement against imitations and enabling the brand to have an ‘eternal life’ through the renewal of its trademark registration.

2.1. Brand as a source of differentiation

There seems to be a common agreement within different disciplines, including law, economics, and marketing, that the use of brands, over time, has relied on evolving interpretations of the concept of ‘differentiation’.Footnote3 Differentiation in a brand relates to its capacity to set itself apart from competition, by associating a superior performing aspect of the product or service it relates to with customers benefits. Historically product differentiation was very important in helping consumers distinguish good quality from bad, and in providing a reassurance about its origin. This has always been a problem inherent in the business world, but was particularly relevant for proto brands, before trademark law came into place (Schechter, Citation1925). This ability of proto brands to enhance consumer information concerning quality and other characteristics of products such as its origin, was very important in reducing uncertainty of transactions. They also worked as a kind of sunk cost associated with reputation building (Akerlof, Citation1970; Alchian & Allen, Citation1977; Klein & Leffler, Citation1981). Proto brands were created not only by the producers or sellers of the goods, but often involved other stakeholders such as retailers in charge of building reputation for the goods of particular regions (Alexander & Doherty, Citation2021). For instance, in medieval England, France, Germany and Italy it was common for guilds to require producers from particular regions to use collective marks associated with their type of business activity. This practice strengthened the hold of the guild upon the trade by assuring that its members conformed with quality standards and that they helped build a collective reputation for the guild and the region (Belfanti, Citation2018). A similar phenomenon is also visible with the early development of self-regulating industry associations in the nineteenth century, in countries such as Meiji Japan (Lopes & Shin, Citation2021).

When compared with proto brands, modern brands are considered to be a relatively recent phenomenon, developing in the second half of the nineteenth century, essentially in the Western world. This is the period of the first global economy, when geographical distances between producers and consumers became common in business, and urban areas expanded rapidly with high concentrations of populations. Many businesses saw the scope of their activities changing from regional to national and also global. In more advanced countries such as the United States, these developments led to the emergence of the modern, vertically integrated, multidivisional corporation which relied on economies of scale and scope at all levels of activity. There was also a marketing revolution, which meant that alongside the development of the modern brand, businesses created mass marketing strategies aimed at reaching a wide range of customers dispersed geographically (Chandler, Citation1959, Citation1962, Citation1977, Citation1990). A revolution in transportation and containerisation facilitated these processes, in particular sales at long distance (O’Rourke & Williamson, Citation1999). It became of the utmost importance to both vendors and purchasers that the goods sold should be what they were intended to be, and that imitations of well-known names, marks, and labels should be prevented (Corley, Citation1993; Grocer, Citation1868; Tedlow, Citation1990). The introduction of trademark law in different parts of the world from the second half of the nineteenth century was meant to protect innovators and also consumers against adulteration, falsification and fraud in large scale trade activities (Lopes & Duguid, Citation2010; UNCTAD Secretariat, Citation1979).

The information provided by brands has, therefore, changed over time, responding to different types of environments, levels of globalisation and technological change. Industrialisation and mass production moved the power of brands more to producers aiming to differentiate their products, while allowing the units of a given variety to be the same. Trademarked commodities appealed to consumers because they made quality and price comparisons easier, and this facilitated decision-making. They also appealed to the retailer in particular when such commodities were pre-packaged and standardised and, therefore, had a longer shelf-life. Additionally, they also reduced the need for skilled salesmen and increased the speed of consumer throughput in the shop (Casson, Citation1994).

While the reference to geographic indication of origin as a source of differentiation was essential for the proto brand, it lost some of its significance over time, except in some industries where provenance remained central as part of the reputation and differentiated imagery of brands. An example can be seen in Paris and its reputation in ‘Haute couture’, which meant that from the mid- nineteenth century fashion designers based in this city started using the geographical origin as an important source of differentiation, associated with high quality and unique design, which are still important in today’s luxury fashion industry (Bayly, Citation2004). In the present day value chains have become vertically and horizontally disintegrated globally, which means that products have components produced in multiple countries. In some industries such as the Swiss watch industry, where the country of origin still matters, for product differentiation and brand reputation, firms can only outsource certain percentages of the finished product outside Switzerland to be able to claim and label the goods as ‘Swiss Made’ in their watches.Footnote4

2.2. Brand as a legal mechanism

Through legal registration, firms have the ability to enforce the law and protect the intellectual property associated with their brands, and therefore inhibit imitators. Trademark laws and trademarks help promote economic efficiency, by creating trust for consumers, reducing search costs, and facilitating repeat purchases (Landes & Posner, Citation1987). Trademarks also help reputable goods obtain price premiums (Akerlof, Citation1970). Trademarks also work indirectly as a source of differentiation, and can help reinforce the claims and ‘personality’ created through marketing strategies to become more truthful in the eyes of consumers. For instance, in 1862, before trademarks came into place in Britain, trust in brands was very limited. Brands were often considered to be inventions for disguising the truth about products. This was because the same brand names could be used by the innovators as well as by imitators with little or no consequences. This was particularly concerning in the food and drinks industry where people’s health could be harmed (Lopes et al., Citation2020). Until trademark law came into place, protection from imitation and fraud in trade was fragmented and ineffective, drawing on a variety of jurisdictional sources. In England, for instance, the statutory systems for such cases tended to be confined to specific trades (Bently, Citation2008).

3. The South American tea industry and registration of trademarks in Brazil

3.1. A ‘born global’ industry

The Brazilian South American tea industry developed as a ‘born global’ industry in the second half of the nineteenth century. During the period from 1855 until 1920 an average of 91 percent of all the Brazilian production of South American tea was exported (Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia Estatística, Citation1986, p. 85). Exports focussed essentially on countries in the Rio de la Plata region - Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, and Chile.Footnote5 The development of this industry in Brazil was the result of an opportunity that emerged with the War of the Triple Alliance. The war, (1864 to 1870) took place between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance, including Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay, and related to issues of boundary of territories and tariff disputes (Daniel, Citation2009, p. 22). Before the war Paraguay had been the largest producer of South American tea in the world (Folch, Citation2010). The war devastated the economy of Paraguay including the South American tea industry and its plantations. Two thirds of the population in Paraguay died, of which 90 percent were men (Bethell, Citation2018). While Paraguay had developed a leading industry in South American tea, the actual plant was also native in Brazil. Brazilian South American tea production was first explored by the Jesuits in the eighteenth century, being exported to the Rio de la Plata region. However, that activity was never significant. It was only with the Triple Alliance War that the Brazilian South American tea industry developed on an industrial scale, taking advantage of the fact that there were already well-established consumer markets in South America, and that the main supplying market had been decimated. Soon Parana became the main producing and exporting region of Brazil, followed by three other regions - Santa Catarina, Mato Grosso and Rio Grande do Sul.Footnote6 For instance, between 1910 and 1912, Parana contributed to about 75 percent of the production of South American tea from Brazil. The increasing significance for the industry, contributing to about 75 percent of the Parana economy, had a central role in the region’s political and economic emancipation from the state of São Paulo during the period 1853–1929 (Costa, Citation1995; Daniel, Citation2009; Filho, Citation1957; Gregório, Citation2015; Mazuchowski, Citation1989).

As with other black tea and coffee, this beverage contains caffeine as well as other psychoactoves alkaloids. Despite multiple attempts during history to internationalise South American tea beyond South America to regions such as North America and Europe, it never succeeded. While consumption habits for tea, coffee and chocolate drinking expanded very fast in Europe and north America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that was not the case for South American tea, which was only able to expand in the continent where it was produced (Folch, Citation2010; Liu, Citation2020). The taste did not attract other cultures. But there were also other factors that contributed to that, such as the fact that the South American tea industry developed at the same time as the Brazilian coffee industry. Coffee had a flavour that appealed much more to consumers in other continents.Footnote7 There was also resistance from countries such as Britain to avoid the competition with their own tea producers based within the British Empire (Liu, Citation2020). The regional concentration of a consumer market in Latin American countries explains why this beverage is known internationally as South American tea (Converse, Citation1940, p. 5; The Pan American Union, Citation1916).

3.2. Trade and trademarks

The South American tea industry stands out for having a relatively high number of trademark registrations in Brazil in relation to other food and non-food classes from 1875 to 1913. As illustrated by , this is particularly striking because this industry was not as significant in the Brazilian economy and in international trade as other industries such as coffee or rubber.

Table 1. Exports and Trademark Registrations (TMs) of South America tea and coffee from Brazil, 1875–1913.

While coffee contributed to 59 percent of Brazilian exports during the period 1875–1913, it only accounted for 1.5 percent of total trademarks registrations (and 10.8 percent of registrations in food). In contrast, South American Tea which only contributed to 2 percent of Brazilian exports, accounted for 2.5 percent of total trademark registrations (and 18.4 percent of registrations in food). South American tea registrations were in fact the largest number of trademarks registrations in a single product category during the period of analysis.Footnote8

In Brazil there was a significant decoupling between the development of trademark law and the corporate branding strategies followed by firms (Lopes & Duguid, Citation2010; Lopes et al., Citation2018). Despite being one of the earliest countries in Latin America to create a trademark law in 1875, and for being one of the original signatories of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property in 1883,Footnote9 the legal trademark system developed was ineffectual and rudimentary, when compared to more advanced countries such as France or the United Kingdom (Lopes & Duguid, Citation2010). It was strongly influenced by French law, which became almost a universal influence in the world during the nineteenth century, and also by other countries such as Portugal, Spain, The Netherlands and England, all important trading partners with Brazil. The first law created that dealt with intellectual property in Brazil dates back to 1809, as a result of the arrival of the Portuguese Royal Family to Brazil and the incentives created by the Crown for entrepreneurs to innovate. But it is only in 1875 that a system of registration of trademarks emerges in Brazil. Apart from the urge to modernise and industrialise, and enhance national and international trade and investment relations, a court case known as ‘Moreira & Cia. vs. Meuron & Cia.’ involving imitation of a snuff brand was at the origin of the first trademark law of 1875 (Lopes et al., Citation2018).

New laws were passed when Brazil joined the Paris Convention in 1883. This meant that the Imperial Government had to tailor its own legislation to agree with the international terms set out in the Convention in areas where domestic law had been previously silent. However, it is only in the early twentieth century, with the new trademark law of 1904, that there was an adequate acknowledgement of the topic of unfair competition, whereby imitation and counterfeit were punished with fines and in some circumstances incarceration (Decree Law nº1,236, Citation1904).

When the trademark law first came into place there was no formal classification system for the registration of trademarks by industry and for a while two alternative systems of physical registration – at state level and national level – existed simultaneously. However, the additional administrative complexity that the state level system of registration entailed (which also involved notification of the Rio de Janeiro trademark office, and the publication of the certificate of registration), meant that very few firms registered at state level followed the procedures to also register trademarks at national level. This meant that a large number of brands registered regionally never appeared in the national registers, and therefore, did not in fact have full protection of their intellectual property (Decree Law nº 2,682, Citation1975; Decree Law nº 3,346, Citation1887; Decree Law nº 9,828, Citation1887; Decree Law nº 1,236, Citation1904).Footnote10 It is only from 1923, with the creation of the ‘Diretoria Geral da Propriedade Industrial’, that there is an adequate and consolidated system of registration at national level (Decree Law nº 16,264, Citation1923). Another major difference in relation to more developed countries relates to the total number of trademarks registered, as well as the lower number of per-capita registrations.Footnote11

From 1906, with the introduction of a compulsory national system of registration and with the accession of Brazil to the Pan American Union, the number of firms registering trademarks more than doubled between 1905 and 1907.Footnote12 The changes in the law also toughened the punishment by imitators and indirectly encouraged many businesses to register their trademarks for the first time. The first industry census in Brazil in 1907, and the National Exhibition of 1908, which was set up to celebrate the centenary of the opening of Brazilian Ports to international trade and the end of the monopoly of the Portuguese, also contributed to a boost in registrations.Footnote13

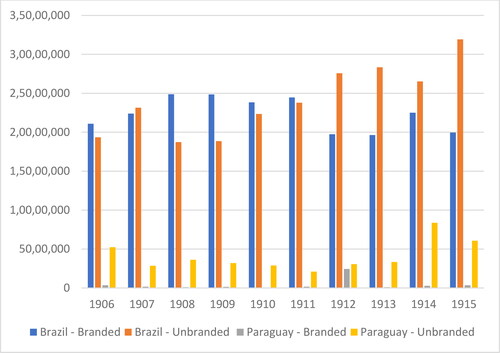

Argentina was the main market of destination of South American tea. For instance, between 1910 and 1912, this market absorbed around 73.7 percent of all Brazilian exports of South America Tea, followed by Uruguay with 20.8 percent, Chile 5.4 percent, and other markets corresponded to a residual amount of 0.1 percent.Footnote14 Despite the high levels of consumption of South American tea, Argentina was traditionally not a producer of this commodity. For most of the period of analysis, 98 percent of Argentina’s consumption of South American tea relied on imports, with Brazil always being the most important market of origin. Initially imports of South American tea from Brazil were mainly of branded and finished goods, but from 1912 semi-processed and unbranded tea surpassed branded exports (See ). For instance, between 1906 and 1911 an average of 57 percent (corresponding to an average of 2,829 thousand contos) of branded South American tea was imported by Argentina from Brazil. The second market Argentina imported from was Paraguay. It was much less significant, and the imports were essentially of unbranded South American tea. Nonetheless Paraguay never corresponded to more that 14.6 percent of total imports by Argentina for the period of analysis (Vallaro, Citation1916, pp. 22–27). As part of its protectionist policies, large plantations developed from 1898 in Argentina, but the first significant crops were only obtained in 1913 onwards. The development of a local industry combined with Argentinian protectionist policies, eventually led to the sharp decrease of Brazilian exports of South American tea to this market, in particular from the late 1920s, and to a decline of the Brazilian industry leadership (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, various years).

3.3. Protectionism and taxation in the Brazil South American tea industry

Long before the Great Depression, usually considered to be the period when protectionism developed in world business relations, Latin American tariffs were far higher than anywhere else in the world.Footnote15 This period, from at least 1865 to World War I, is also considered to be characterised by a revolution in treaty-making (Keene, Citation2012). While there were some multilateral agreements, the prevalence was for treaties to be bilateral, based on principles of reciprocity, providing special regimes for particular products traded between states. In the case of Brazil these treaties involved not only neighbours such as Argentina but also other countries such as the United States, which in the late nineteenth century and first part of the twentieth century was a key destination of Brazilian exports and origin of its imports (Anuário Estatístico do Brasil - Repertório Estatístico do Brasil, 1939–Citation1940).

The explanations for protectionism tend not to rely solely on domestic output gains obtained as a result, but also on state revenues, strategic responses to trading partners’ tariffs, and the need by Latin American countries to compensate for the fact that they had lost out on the first globalisation wave (Bulmer-Thomas, Citation1994, p. 141). The South American tea industry was no exception to these trends, with Argentina often increasing tariffs on imports of finished and branded tea.Footnote16 These protectionist policies imposed by Argentina to Brazil had a series of implications. In 1889 Brazil reduced substantially its tariffs to imports from the United States. These were subsequently decreased which culminated in a reduction of 20 percent in 1906 (Decree Law nº 6,079, Citation1906). The United States which was the main market of destination of Brazilian coffee, immediately increased its exports of flour to Brazil. This had important implications for trade with Argentina, traditionally the main origin of flour consumed in Brazil. As a reaction to these favourable concessions given by Brazil to the United States, the Argentinian government tried to negotiate a similar arrangement with Brazil. As that was not achieved, there were further rises in the tariffs to the imports of branded South American tea (Cervo & Bueno, Citation2002). There was a tariff war at country level. In 1885 Argentina created tariffs of 15 percent to imports of finished and branded South American tea from Brazil, imposing no tariffs to semi-processed and non-branded tea. In the same year, in Parana local legislation was created to tax exports of semi-processed and non-branded South American tea by 15 percent, leaving the processed and branded tea non-taxed (Decree Law nº 810, Citation1885). While taxes were important for the industry, and aimed to protect its international reputation and also the development of the economy of the region, they essentially protected the big businesses, which were the main producers of branded and processed tea. Most of the owners of the largest South American tea firms also had political, military, or administrative roles, through their participation in committees and public institutions, where decisions were taken about the allocation of funds collected from taxes associated with the South American tea trade.Footnote17 For instance, the funds from taxes collected were frequently used in the building of new infrastructures such as water supplies, railways, electricity and telephone cables, which facilitated the development of business activities of the large South American tea producers. While the largest firms producing and selling finished and branded South American tea, paid lower or no local tax because they essentially sold branded goods, small businesses, most of which produced semi-processed unbranded tea, paid relatively much more taxes and were, therefore, left much more vulnerable as well as the economy as whole (Nogueira, Citation1862). The 1885 tax to exports from Parana of semi-processed and non-branded tea did not apply to other producing regions of Brazil, which lead to an increase of exports of semi-processed and non-branded tea from the other Brazilian producing regions of South American tea - Mato Grosso, Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.

There were other implications associated with this tariff war between Brazil and Argentina. There was an increase of indirect exports to Argentina via Montevideo, as there were no tariffs imposed by Argentina to South American tea imported from Uruguay. The press at the time estimated that over one third of the exports to Montevideo, not just of South American tea, but also of other commodities such as sugar, coffee, brandy, and tobacco from Brazil, were re-exported to Buenos Aires and the Argentinian Confederation (Souza, Citation2019). This process of exports of semi-processed and unbranded goods to Uruguay led to a proliferation of adulterations and imitations of South American tea at various levels in the value chain ranging from processing to retail.Footnote18 Despite the presence of transaction costs associated with tariffs, there was hardly any foreign direct investment through the setting up of offices abroad by Brazilian South American tea producers, for the final processing and branding of the tea to be sold in key markets such as Argentina. Companhia Mate Laranjeira from Mato Grosso is an exception. The firm set up an office in Argentina in 1894. Until then it had been selling in the Rio de la Plata region through agents. In Argentina the agent was the firm Francisco Mendes Gonçalves & Cia, established in Buenos Aires in 1874.Footnote19 In 1894 Companhia Mate Laranjeira integrated vertically by acquiring the production unit of its agent/distributor. While the Argentinian office of Companhia Mate Laranjeira finished the processing of South American tea and branded the product, its agent, Francisco Mendes Gonçalves & Cia, remained the exclusive distributor of the tea in that market as well as in other countries of Rio de la Plata (Companhia Mate Laranjeira, Citation1895). From 1896 this Brazilian South American tea producer invested in other foreign markets beyond Argentina setting up offices in Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro and in Philadelphia, where until then they had also operated with agents (Jornal do Commercio, 1896, pp. 8-9; idem, 1900, pp. 6). A few years later, the situation changed radically, with the main shareholder of Companhia Mate Laranjeira, the Banco Rio e Mato Grosso going bankrupt. In 1903 this led the Argentinian agent Mendes Gonçalves to acquire the majority of the shares of the Brazilian Companhia Mate Laranjeira and to move the headquarters of the newly formed company Laranjeira, Mendes & Cia to Argentina (Queiroz, Citation2015, p. 10).

3.3.1. Top firms registrants of South American tea

Since its early development, the Brazilian South American tea industry was highly concentrated in the hands of a few entrepreneurs in all the four main producing regions of Brazil. A similar pattern can be identified with the registration of trademarks within the South American tea industry with Parana having a much higher number of registrations than the other regions. This was associated with Parana’s state policies of only selling processed and branded South American tea (and imposing taxes to exports of unprocessed tea), as opposed to other regions where no such taxes existed for semi-processed and unbranded tea. From 1875 to 1913 the top seven registrants correspond to 61 percent of the total trademark registrations in South American tea. In the regions of Mato Grosso and Santa Catarina two monopolies developed. In Mato Grosso, the already mentioned Companhia Mate Laranjeira was established in 1882, resulting from the concession of a large portion of land by the local government to one entrepreneur. It soon became vertically integrated, exporting essentially unbranded and semi-processed South American tea (Krauker, Citation1984; Queiroz, Citation2008). These concessions generated a controversy between states which led to a civil War of the Contestado where different regions disputed some land between adjoining states. In the region of Santa Catarina another monopoly was formed in 1890 - Companhia Industrial Catarinense. The newly formed company was the result of the merger of several small businesses (Almeida, Citation1979, p. 26). In Parana there was no monopoly, but rather a highly concentrated industry. The industry leaders which were also the main registrants of South American tea trademarks, included Manoel de Macedo (later renamed Macedo & Filhos) (Costa, Citation1995), Guimarães & Co., A. Baptista & Ca, Francisco F. Fontana, David Carneiro & Co., B. A. da Veiga and Viúva Correia & Filho. Diversification into related and unrelated activities was quite common among industry leaders (Chaves, Citation1995, p. 105). For instance, Manoel Antônio Guimarães, known as the Viscount of Nacar, established Guimarães & Cia - one of the largest producers of South American tea. A very prominent businessman in Parana in the second half of the nineteenth century, Viscount of Nacar, accumulated various top political and administrative roles in the region, including being part of the committee in charge of legislating the activity of South American tea industry. He owned vast areas of plantation land and manufacturing units to process and package the tea. He also owned ships to transport the finished and branded goods to markets in Rio de la Plata. Apart from that, the Viscount of Nacar diversified his businesses into the importing of a wide array of goods such as salt, rice, flour, sugar, coffee, wine, leather, and tools. Additionally, his company also had agency agreements with foreign and domestic banks and insurance companies.Footnote20

3.3.2. Decoupling differentiation from the law in the concept of the brand

The coupling that is implicit in the concept of the modern brand between differentiation and the law works in two ways. On the one hand, firms, in order to design appropriate corporate tactics and strategies such as the creation of alliances in distribution or franchising agreements, need to be aware of changes in trademark laws and the impacts that court cases regarding trademarks and brands might produce (Cohen, Citation1986, Citation1991; Higgins, Citation2008, Citation2010). On the other hand, legislators when creating new laws need to take into account the exact role of brands in firms’ strategies and the possible benefits or harm they can pose for markets and to different stakeholders, ranging from other businesses, government, industry associations and consumers. Legislators also need to make sure that the registration systems are effective and that the law can be properly enforced, information is not expensive to obtain and business strategies can easily deal with any changes in the law (Casson, Citation1994; Desai & Waller, Citation2010, p. 1425). In the Brazilian South American tea industry this coupling between strategies and the law did not exist.

In a period when trademark law had just been introduced in the country in 1875, while there is evidence of registration of trademarks and some early forms of marketing to create differentiation, there is no perfect transition from the use of proto brands to modern brands. The marketing techniques used for creating differentiated products in the Brazilian South American tea industry were quite rudimentary. Firms created multiple brands directed to different customers for products which were basically the same commodity and not very differentiated. Rather than creating unique personalities for brands, South American tea labels focussed on highlighting its Brazilian origin, which in the Rio de la Plata region was associated with superior quality and better taste, and which matched the tastes of consumers. The main purpose for the registration of South America tea trademarks was to create differentiation and guarantee the genuine origin, purity, and overall quality (flavour, smell, colour, and taste) of the tea. Trademarks were used as part of firms’ strategies aimed at shaping consumer preferences rather than as actual mechanisms to protect the intellectual property associated with brands Citation1916.Footnote21

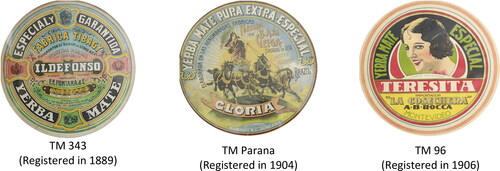

The physical labels combined information about the product with attractive images (See for some illustrations). The information provided in the labels usually included the actual brand name, the name of the firm and the geographical origin (usually the city, the state, or the country, or a combination of these). Smaller firms often included the name of the importer and their location as part of the information in the label. This emphasis on the importer reflected the low bargaining power smaller firms had in the South American tea value chain, and the high levels of competition they had to face. Other information also often appearing on labels included the year of foundation of the producing company (and sometimes the importing company or agent), and the name of the lithographer that had printed the label. The actual names of the brands tended to be of three types. They either referred to names of people, to names of animals, or to mythological names. The most frequent brand names related to people, usually the owners of the firms such as ‘Ildefonso’, which was the first name of the owner, Ildefonso Pereira Correia, also known as the Baron of Serro Azul (see TM 343 in ). Names of the children of the owners of the firms or other relatives were also common.

All the information in the labels tended to be written in Spanish, the language of the host countries in Rio de la Plata. A commercial agreement drawn between Argentina and Brazil in 1901, allowed all trademarks registered in Brazil and Argentina, to have immediate legal protection in the other country. This explains why so many South American Tea trademarks were registered in Brazil in the Spanish language and hardly any Brazilian South American tea trademarks are registered in Argentina (Convenio entre la República Argentina y los Estados Unidos del Brasil sobre Marcas de Fábrica y de Comercio, Citation1901). By adapting the brands and trademarks to the local markets and cultures, firms helped reduce uncertainty and risk in the eyes of Spanish speaking consumers and increased customer loyalty. Labels had different sizes, but tended to be round, so that they could be used on the top of wooden barrels of different but standardised sizes. The packaging used for South American tea also changed over time. Traditionally South American tea was packaged in leather containers. However, from the 1870s, competition between different regions of Brazil, and the need to make the product more attractive in international exhibitions and in international markets, led the Parana producers of South American tea to change the packaging of their goods, to improve its life, taste, appearance in the eyes of consumers and the intrinsic quality of the product in general. New packaging styles developed ranging from wooden barrels, to cotton bags, paper packages and later to cans (Presas & Presas, Citation2007; Relatórios da Provincia do Parana, Citation1876, pp. 112–113). Product design became a key factor in developing and marketing South America tea as a way to create differentiation. The first designers were often expatriates from Europe and had the knowledge and experience of producing colourful illustrations and designs used for lithography (Moore & Reid, Citation2008).

The marketing and advertising techniques that South American tea firms used were quite primitive when compared with those adopted by leading firms in developed countries (Church, Citation2000; Fraser, Citation1981). Rather than focussing on long-term brand loyalty, marketing communications in South American tea essentially aimed to generate product recognition. South American tea firms did not rely on any professional advertising services. In fact, there were no advertising agencies in Brazil until 1914.Footnote22 This was quite late when compared to other countries such as Britain which had advertising agencies as early as the 1830s (Nevett, Citation1982). The main sales promotion tool used was the presence at international exhibitions. South American tea appears for the first time at international industry fairs in Vienna in 1873, Amsterdam in 1884 and twice near Paris in 1885 (in Vincennes and Saint-Maur) (Santos, Citation1969). Through their presence in exhibitions South American tea firms showcased their goods and the producing regions of Brazil. They also learned how to become more competitive by improving quality and adapting the product to consumer tastes. Overall these exhibitions helped reinforce Brazil’s national identity and its industries of specialisation. Additionally, they contributed to the increase of imports of new merchandise into Brazil, to the flows of ideas and exchange and transfer of knowledge and new cultural values and imagery, very much appreciated by the native bourgeoisie.

In late nineteenth century Brazil, there was a fast development of the press and lithography industries with many new newspapers, books and magazines being printed.Footnote23 Nonetheless South American tea producers hardly used the press to advertise their goods during the period of analysis. For instance, for the period 1870–1919, the top eight registrants of South American tea altogether advertised their brands 156 times, appearing in 57 different newspapers. These press adverts by South American tea producers tended to have no images and read more like pieces of news (as most adverts in Brazil did at the time) and essentially tended to highlight the presence and success of the firms’ brands in international exhibitions (See for instance Herva Matte do Parana, Citation1882; Herva Matte em Pacotes Marca Ildefonso, Citation1886; Ilex-Mate – Marca Registada Fontana, Citation1883). This contrasted for instance with the multinational enterprise J. & P. Coats present in Brazil, which alone advertised 19 times more in the same period with a total of 5,640 adverts, appearing in 163 different newspapers. J. & P. Coats was a leading British multinational in fine thread which had initially started exporting to Brazil by using agents, and which in 1879, set up a subsidiary which relied on very aggressive and advanced marketing strategies to sell in that market (Lopes et al., Citation2018, p. 9, 11). Another distinguishing difference between the firms in South American tea industry and the foreign firms which had adopted modern brands relates to the types of distribution channels used. While South American tea producers relied essentially on third parties such as agents; foreign firms adopting modern brands used different modes of entry into foreign markets according to the strategic importance of those markets (Lopes & Casson, Citation2007). Agents distributed South American tea in alternative ways, either by selling through their own shops, by acting as intermediaries between producers and retailers, or by selling directly to private homes (Sampaio, Citation1921). In markets such as the United States, the agents distributing South American tea often also distributed Brazilian coffee, and they used the success coffee was achieving to try to introduce South American tea by providing free samples to customers buying coffee (Moraes, Citation2014, p. 11). The concern with internationalisation led to the creation of South American tea industry associations as a way to increase the collective bargaining power in global value chains. These associations, among other initiatives, tried to develop a consumer market in North America and Europe which never succeeded, given the high predominance of coffee from Latin America, and tea originating from Asia, in particular India and China (Liu, Citation2020). Later on, these associations developed other activities with significance in the industry such as controlling and certifying the quality of the goods for exports, and negotiating taxes.Footnote24

Looking at the second component of the modern brand – the legal protection of the intellectual property, there is wide evidence that while South American tea producers registered more brands than other industries such as coffee, and that Brazil was an early adopter of a trademark law, the use of the law was different from that of firms and industries which by the last quarter of the nineteenth century had adopted the modern brands.Footnote25 Trademark law was supposed to provide exclusivity to brands that were registered and prevent imitation. Nonetheless, of all the court cases that took place in Brazil during the period of analysis there are no cases involving South American tea.Footnote26 In contrast, leading multinationals in their product categories which had invested in Brazil, such as Singer Sewing Machines from the United States, Chartreuse liqueur from France, and Apollinaris water from Great Britain, only registered a limited number of trademarks and filed cases to sue local imitators.Footnote27 Unlike South American tea producers these firms also used multiple marketing tools to build unique ‘personalities’ for their brands.

4. Framework for unbundling the concept and the functions of the brand

The standard accounts pointing to a dichotomy in terms of the role brands may perform for firms - either as proto brands or as modern brands - assume that the relationship between trademark laws and branding practices is symbiotic. This means that changes in trademark laws help to create and improve brand personalities and vice versa (George, Citation2006). The implicit assumption is that firms which register trademarks automatically benefit from the protection of their intellectual property, and that they have the required the skills and knowledge to make effective use of marketing strategies and tools in creating personalities for their brands.

The evidence provided in the previous sections about the use of brands in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Brazil South American tea industry shows that new trademark laws meant that the evolution from the use of proto brands by firms (which provided basic information about quality and origin of goods), did not immediately lead to the adoption of modern brands (which meant rewarding investments in ‘permanence’ and discouraging ‘fly-by night operations)’ (Demsetz, Citation1982). There was no clear and automatic coupling between differentiation and the law. Instead, firms relied on a limited number of marketing tools. While there was registration of trademarks, the protection of the intellectual property was not being enforced. Trademark registrations were instead used to create differentiation in a highly competitive and protected market.

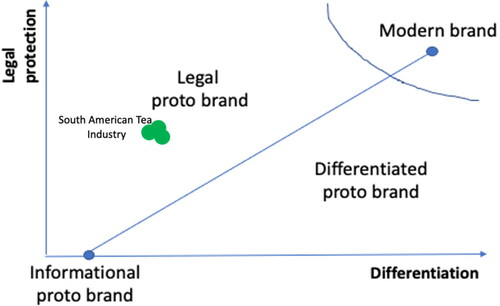

This use of the concept of the brand, somewhere between the proto brand and the modern brand, is particularly visible during periods of institutional transition, such as the period analysed here when trademark law first came into place in Brazil which had an environment characterised by poor institutions and a weak legal system (Spitals, Citation1981; UNCTAD Secretariat, Citation1979). below unbundles the concept of the modern brand to consider these hybrid alternatives. It considers two axes associated with the two key distinctive characteristics of the modern brand – the use of the brand as a source of differentiation to inhibit competition, and its legal protection which implies the ability to enforce it and prevent and prosecute imitators. There are different areas in , corresponding to alternative predominant uses of the brand. The so-called proto brand is here renamed as ‘informational proto brand’. It corresponds to the historical use of brands when they provide information about the quality and origin of the product. As mentioned previously, it contrasts with the modern brand which is characterised by high levels of differentiation and use of legal protection through registration and strong enforcement of intellectual property. considers two further types of uses of the brand by businesses, leading to four typologies of brands: besides the ‘informational proto brand’, and the ‘modern brand’, it also considers the ‘legal proto brand’, and the ‘differentiated proto brand’. Brands are symbolized by circles. Informational proto brands intersect with the axis associated with the level of differentiation of the brand, meaning that even without any legal protection, brands that have existed for millennia, have always tended to have a minimum level of differentiation providing information about the quality of the goods and their origin.

‘Legal proto brands’ and ‘differentiated proto brands’ correspond to two intermediate uses of the brand by firms before fully adopting the modern brand. Within the ‘legal proto brand’ area (on the left hand side of ) firms may be merely registering their trademarks, in which case they appear positioned closer to the lower part of that quadrant, as firms are not taking advantage of the law to protect their intellectual property through courts. Firms move towards the top of the axis as they become more active in developing strategies targeted to protect their intellectual property and enforcing the law when faced with imitation. Legal proto brands are more characteristic of industries where products are not really differentiated and are therefore easily replicated. They tend to be associated with markets that are easier to enter. Firms create differentiation for their otherwise non differentiated goods by saturating the market through trademark registrations. The South American tea industry (illustrated in Figure 1 with multiple circles symbolising brands) is an example of that. While in a less developed country such as Brazil this type of strategy is visible at industry level, in developed countries such as Britain it is also possible to find such strategies at firm level. The British soap and toiletries producers Crosfield’s and Gossage, which until Lever Brothers entered the market in 1884 were industry oligopolists, are relevant examples. These firms historically controlled the market for tablets of toilet soap, using very actively modern brands. Lever Brothers, by branding and selling packaged soap, revolutionised the business methods and the way household and laundry soaps were marketed. With the launch of a branded soap ‘Sunlight’, which was also registered as a trademark, the firm protected its intellectual property very actively and pursued vigorously any imitators in the domestic market and abroad. They also invested heavily in marketing and advertising, creating a unique personality for the brand. Joseph Crosfield’s from Warrington and William Gossage from Liverpool felt the competitive pressure created by Lever Brothers and followed by registering many new soap and chemicals trademarks, and investing in marketing, in particular from 1886 and 1887. Unlike Lever Brothers who just registered a very small number of brands, both Crosfield’s and Gossage were registering many trademarks each. Further, they did not internationalise their brands and did not invest in the protection of the intellectual property of the brands from imitators (Lopes & Guimarães, Citation2014; Musson, Citation1965, p. 104, 181). As with South American tea, these two British firms - Crosfield’s and Gossage - were using ‘legal proto brands’ as they were registering labels to create differentiation for their products for near retailers and consumers. These two firms ended up being acquired by Lever Brothers in 1919 (Wilson, Citation1954).

The other area on the right-hand side of relates to the ‘differentiated proto brand’. It is associated with cases where firms invest in differentiating and building personalities for their goods, but do not develop effective strategies for protecting the intellectual property of their brands. In this case firms tend to invest heavily in different forms of communication to advertise their brands’ uniqueness. Firms might register trademarks for their goods but tend not to take advantage of their ability to prosecute imitators. An illustration is the British brand Pears soap whose chairman in the late nineteenth century was Thomas Barratt. He was honoured by the press for his unique advertising skills and was considered as the father of British advertising. The soap was very innovative for its time with an oval shape and was translucid. The communications and advertising of the brand was also a major innovation. Barratt hired reputed artists such as the pre-Raphaelite Millais to draw and paint adverts and also celebrities such as Lillie Langtry (a famous actress notorious for her beauty) to endorse and help create a personality for the brand (Good Morning! Have you used Pears Soap?, Citation1889). By the time the trademark law came into place, Pears had already achieved an international reputation and was being sold in different continents. While Pears registered three trademarks after the law came into place, the firm did not invest in prosecuting imitators around the world. The secret process for making the soap could not be replicated exactly, but imitators were producing counterfeit bars of identical shapes and packaged in almost exactly identical wrappers as Pears. The brand and the firm did not survive and was eventually acquired by Lever Brothers in 1915, which immediately used modern brand techniques in the management of Pears. Among other strategies, Lever Brothers radically changed Pears’ mode of entry into foreign markets in order to deal with imitators. The multinational firm set up wholly owned distribution channels in markets that were considered strategic and, when possible, sued imitators, who were often their own distributors, and other agents (Lopes & Casson, Citation2007, Citation2012).

5. Conclusion

This study unbundles the concept of the modern brand to illustrate how historically there has been a wide variety of ways through which firms have used brands in their growth and survival strategies. Rather than evolving in a dichotomous way from proto brands to modern brands as conventionally acknowledged, brands have evolved and have been used in distinct forms. Modern brands are considered to have developed in the late nineteenth century from fast technological innovations, industrialisation, and the development and liberalisation of markets. These developments did not take place everywhere and at the same pace across the world. This meant that not all nations, industries and businesses were able to develop brand strategies that coupled differentiation with legal protection and the enforcement of their intellectual property. This was because there was either no trademark law or because firms did not have the skills to develop adequate differentiation strategies. In developed countries this decoupling between firms’ strategies and the law was more common at firm level as some firms did not have the capabilities and resources which enabled them to make the automatic transition from proto brands to modern brands. When they operated in industries where their main competitors were able to make that transition in a symbiotic way, they often ended up perishing. In less developed countries such as Brazil it is easier to find this uncoupling between differentiation and the law in a more generalised way at the industry level, as illustrated by the case of the South American tea industry. Brands were not used by firms as investments in permanence aimed at creating ‘eternal lives’ for those brands, but rather as fly-by-night operations lacking strategic purpose. Firms across the same industry ended up becoming vulnerable to international competition and to other challenges such as protectionism, and that greatly impacted the long-term dynamics of the Brazilian South American tea industry.

Finally, this study contributes to the growing literature which argues that trademark registration data can provide new angles for analysing different economic phenomena. There is a wide literature which highlights that modern brands are dynamic in nature and that firms should constantly adapt their strategies to different consumer preferences, needs, emotions and cultures. In an industry characterised by the production of what was essentially a commodity, with very little differentiation, firms registered large numbers of trademarks as a way to create differentiation and unique brand personalities for consumers, and to deal with competition. Brands in the South American tea industry were, therefore, not used in the same way as the so-called ‘modern brands’ were being used in other countries such as Britain and the United States. They did not confer meaningful market power to firms and did not perform all the key strategic functions of modern brands which included the creation of barriers to entry by increasing demand and the adding more value to businesses by allowing firms to, for instance, control prices or to manage quality, by satisfying consumers emotional and psychological needs, by defining national identities, and also by providing a platform for protection of intellectual property against imitators through legal enforcement (See for example Saíz and Castro (Citation2018).). By unbundling the concept of the brand in a period of transition, when the trademark law first came into place in Brazil, this study shows that trademark registrations were used not as a mechanism to protect their intellectual property, but rather as a source of differentiation for commodities in a market characterised by high anti-competitive protectionism.

Acknowledgments

This project benefited from the financial support of the British Academy (Research Grant P M130264), and from the visiting position of Teresa da Silva Lopes as Thomas McCraw Fellow at Harvard Business School. The article also benefited from the very helpful comments of three referees and from the audiences at seminars presented at the London School of Economics and the University of Reading in 2021.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The trademark registration data was collected from Série Industria e Comércio – IC3 (National Archive of Rio de Janeiro), Diário Oficial (Library of the Ministry of Fazenda, Rio de Janeiro, and website JusBrasil), and Boletim da Propriedade Industrial (National Library, Rio de Janeiro). The information about Court cases relating to imitation, adulteration and counterfeit was obtained from the Acervo Judiciário do Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, in particular the collections relating to Corte de Apelação, Juízo Especial do Comércio, Junta Comercial do Rio de Janeiro, Tribunal da Relação do Rio de Janeiro, Supremo Tribunal de Justiça, Supremo Tribunal Federal and Tribunal Civil e Criminal do Brasil. Research on South America Tea was obtained from the following archives: Junta Comercial do Paraná (in particular the Livro de Registro de Marcas, Livro de Registros de firmas); Associação Comercial do Paraná (in particular Boletins da Associação Comercial e nas Atas das Assembléias da Associação Comercial do Paraná; Arquivo Municipal de Curitiba (in particular the folders relating to Romario Martins); Museu Paranaense (in particular the folders relating to Família Leão, Marcas e Rótulos do Paraná e Secretaria de Cultura do Estado do Paraná). Other historical published sources include Almanak Laemmert, Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira (National Library, Rio de Janeiro); Gazeta de Notícias, Correio da Manhã, Correio Paulistano, Diário de Notícias, Jornal do Comércio, Jornal do Brasil, A República, O Paiz, O Auxiliador da Indústria Nacional, Jornal do Recife, A Noite; O Comercial do Paraná.

2 South American tea can be drunk in two ways: as tea or as ‘chimarrão’. These two are different in the way they are prepared for consumption, and the social occasions in which they are consumed. Other possible uses for the herb include suing it as an ingredient for toothpaste, shampoo, perfume, paint, among other industrial uses. South American tea is considered to provide various benefits as nutritional, health drink and as a medicine. It is also considered to be a temperance drink, which stimulates the nervous system without the disadvantages that alcohol might have (Albes, Citation1916; Leão, Citation1931).

3 Examples include, in marketing – Keller (Citation2003) and Moore and Reid (Citation2008). In law see for example, Landes and Posner (Citation1987); in economics see Chamberlin (1933/1962).

4 This is known as the ‘60% rule” that has been in force since 2017. See also Donzé (Citation2011) and Donzé and Veronique Pouillard (Citation2019).

5 Born global companies are characterized by an ability to overcome the initial barriers that are associated with entry into foreign markets without first establishing a strong home market presence (Hennart, Citation2014; Rennie, Citation1993).

6 For instance, between 1910 and 1912 Paraná produced on average 45,818,590 Kgs; Rio Grande do Sul 8,737,432 Kgs, Mato Grosso 4,281,704 kgs, Santa Catarina 4,205,792 Kgs, and other regions in Brazil 25,244 Kgs (Annuario Estatistico do Brasil, Citation1917; Dados da Diretoria de Estatísticas Comercial do Brasil, Citation1935).

7 See for example attempts to internationalise to the United States and to Europe through the introduction of a Law which exempted firms from being taxed for their exports into those markets (Decree Law nº526, Citation1879).

8 The most important industries in terms of trademark registrations between 1875 and 1913 were: food (1996 trademarks), textiles (1909), alcohol (1797), tobacco (1749) and chemical substances (1615). Calculations based on data from Industrial Property Bulletin of the Brazilian National Library, Series Industry and Trade of the Brazilian National Archives and Official Gazette of the Union of Brazil. For the purpose of this analysis all trademarks were classified into 50 classes using the system of registration in Britain, set up in 1875 (Industrial Property Bulletin of the Brazilian National Library; Trade Marks Registration Act, Citation1875).

9 Decree Law nº 2,682 (Citation1875). Brazil was one of the 11 original signatories of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property (20 March 1883). It was one of the intellectual property treaties. Before then, the Brazilian government relied on bilateral declarations to share the protection of trademarks with countries such as France (21 June 1876), Belgium (8 November 1876), Germany (12 January 1877), Italy (21 July 1877), The Netherlands (27 July 1878) and Denmark (25 April 1881). The only country in Latin America to introduce a trademark law earlier was Chile in 1874 (World Development, Citation1979). About Brazil industrialization see Suzigan (Citation2000) and Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Citation1883). Other countries signatories of this International Convention were Belgium, Spain, France, Guatemala, Italy, Holland, Portugal, Salvador, Serbia and Switzerland. Britain joined in 1884. See also Ladas (Citation1975).

10 Between 1892 and 1913 there were 934 trademarks registered regionally in the Trademark Office of Parana. Of these 493 were registered by the leading firms, who also tended to register their trademarks nationally in Rio de Janeiro (B.A. da Veiga registered 23 trademarks regionally in Parana; David Carneiro registered 95 trademarks regionally; Francisco Fontana registered 61 trademarks regionally; Guimaraes & Cia registered 127 trademarks; Macedo & Filho registered 140 trademarks and Viúva Correia & Filho registered 27 trademarks). During the period of analysis all the companies registering at national level also had registered trademarks at regional level. Some firms, such as B.A. Veiga registered the same trademarks at regional and national level. Others, such as Manoel de Macedo registered different trademarks, only having some overlaps (e.g. Guimarães & Cia registered about 25 percent of the trademarks both at national and regional level between 1892 and 1913).

11

12 Decree Law nº. 5,424 (Citation1905): article 2. The pan American Union encouraged firms to register trademarks in Brazil as they became automatically protected in other countries that were part of the Union (Report of the Delegates of the United States to the Third International Conference, 1907).

13 The Brazilian Industry census took place between 1905 and 1907. Several adverts were published in 1906 highlighting how important it is for firms to register their businesses in the census (O Brasil em 1906, Citation1905, p. 1; Inquérito Industrial, Citation1906; Brazil National Exhibition, Citation1908; Wright, Citation1908; Relatório do Ano de 1895, Citation1896; Relatório do Ano de 1907, Citation1908, pp. 24–28).

14 The total exports to of South American tea a between 1910 and 1912 were 184,075,058Kgs: 135,588,309 kgs went to Argentina; 28,327,763 Kgs went to Uruguay, 9,910,986 Kgs went to Chile, and 248,000Kgs to other markets (Anuário Estatístico do Brazil (Citation1917, p. 122).

15 The only exception is the US in the immediate post-Civil war era (Coatsworth & Williamson, Citation2004). On Argentine tariffs see also Alejandro (Citation1967, Citation1970, p. 294), Thompson (Citation1929), Clemens and Williamson (Citation2001), and Coatsworth and Williamson (Citation2002).

16 At country level there was also a response to the increase in tariffs imposed on Brazilian goods, as Brazil created taxes on imports of cereals, in particular wheat (Cervo & Bueno, Citation2002; Linhares, Citation1969).

17 For instance, Manoel de Macedo was Mayor and Council member of the city o Curitiba in Parana (Citation19014). Guimarães, known as Baron and Vicount of Nacar, was the Vice-President of the State of Parana and Coronel of the National Guard (Relatorio com que o Exm. sr. Vice-Presidente da Provincia, coronel Manoel Antonio Guimarães, 2.a Sessão da 10.a Legislatura da Assembléa Provincial do Paraná, Citation1873). A. Baptista was a Federal Member of Parliament and Vice-Governor of the State of Santa Catarina (Almanak Laemmert, Citation1904, Citation1909). José Ribeiro Macedo was a Coronel of the National Guard, and Member of Parliament of the State Parliament of Parana (Dezenove de Dezembro, Citation1886, Citation1889).

18 Imitations produced from other herbs from the same same ‘Ilex’ family as South American tea. A lot of exports from Paraguay included a herb named ‘gemina’ in Argentina a substitute often used was ‘Ilex Aquifolium’ and ‘cogonilla’. Apart from falsifications, there are also herbs that are badly prepared or packaged, changing the flavour and the conditions of the herbs. The first are professional imitators, the latter are just small entrepreneurs with poor machinery and knowledge (Westphalen, Citation1985).

19 Francisco Mendes Gonçalves was an acquaintance of Tomas Laranjeira from when they had fought together in the Paraguay war (Companhia Matte Laranjeira, Citation1941, pp. 6–7; Companhia Mate Laranjeira - Relatorio à Primeira Assembléa Geral de 27 de Maio de Citation1893, 1893; Ronco, Citation1930).

20 These included Banco de Republica dos Estados Unidos do Brasil, The London and Brazilian Bank Limited, do The British Bank of South America, the Banco Emmisor de Pernambuco, Banco Franco Brazileiro, Companhia de Seguros Previdente, Companhia Nacional de Navegação Costeira, Guardian - Fire and Life Assurance Company, Companhia Liverpool Brazil and River Plate Steamers (linha Lamport & Holt) (Notabilidades commerciaes: Guimarães & C. (sucessores do Visconde de Nacar & Filho), Citation1892, Citation1900; Boguszewski, Citation2007, p. 31, 37).

21 A similar pattern can be identified in port wine trade where brands were influential in international wine trade as consumers often lacked the ability to distinguish types of port but relied instead on marks. This historical evidence challenges the view of Stigler and Becker who tend to assume that effective brands adapt to consumer preferences (Duguid; Duguid, Citation2003; Stigler, Citation1961; Stigler & Becker, Citation1977).

22 The first advertising agency - Ecletica, was founded in 1914 in São Paulo. which opened in São Paulo. At the end of World War I more advertising agencies emerged offering professional designs and advertising placements. The American advertising agency J. Walter Thompson pressed to follow one of its clients General Motors, was the first foreign advertising agency to open an office in São Paulo in 1929, and soon after another in Rio de Janeiro (MacLachlan, Citation2003, p. 78; Woodard, Citation2002).

23 The establishment of the newspaper Gazeta do Rio de Janeiro in 1808 was the first vehicle for the development of advertising in Brazil. Advertisement sections included a wide array of adverts ranging from rental and sale of properties, to sale of slaves, and to announcements about consumer goods and food items. This set the process of developing the use of adverts to reach consumers in motion. Around 1850 the first wall posters appeared in the capital and inexpensive printed pamphlets circulated, often touting amazing medical points. New manufactured devices from abroad generally required advertising. In 1858 Singer Sewing Machines began to create a Brazilian market, and 1875 printed illustrated ads in newspapers (MacLachlan, 2003, p. 77).

24 In 1887 the Associação Propagadora da Erva Mate was ctrated. In 1889 the Centro de Exportadores de Erva Mate was created. In 1911 another association Companhia Exportadora d Mate Parana (Companhia Exportadora de Mate do Parana, Citation1911; Decree Law nº 838, Citation1887; Relatório do Presidente da Província Joaquim d’Almeida Faria Sobrinho Enviado à Assembleia Legislativa em 1888, Citation1888).

25 See for example “Regulation” (6 December Citation1854): articles 3, 6-8; Decree Law nº 87 (14 April Citation1862): article 15; Decree Law nº 248, (22 April Citation1870): article 2; and Decree Law nº 349 (8 April Citation1873); “Regulation” (20 April Citation1876): chapter 2. See also Relatórios dos Presidentes de Provincia à Assembleia Legislativa.

26 Cases relating to imitations were found in the following courts in Brazil: Supremo Tribunal de Justiça; Relação do Rio de Janeiro, Junta Comercial do Rio de Janeiro, Corte de Apelação, Supremo Tribunal Federal, Tribunal Civil e Criminal do Rio de Janeiro, and Juízo Especial do Comércio da 1º Vara. This research also drew on the Acervo Judiciário, Arquivo Nacional (Rio de Janeiro).

27 For instance, Singer registered 3 trademarks in Brazil: numbers 1584, 1825, and 2563. Apollinaris also registered 3 trademarks: numbers 1194, 1195, and 1996. Grande Chartreuse registered four trademarks: numbers 193, 988, 989 and 990. Singer Sewing Machines filed 5 five court cases, the French Chartreuse Liqueurs filed 3 court cases, and the British water company Apollinaris water filed 2 courts cases (Decree Law nº 2,682, Citation1875; Regula o Direito que têm o Fabricante e o Negociante de Marcar os Productos de sua Manufactura e de seu Commercio, Citation1876, p. 179).

References

- Almeida, R. P. d. (1979). Um Aspecto da Economia de Santa Catarina: A Industria Ervateira [PhD dissertation, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina].

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (1939–1940). Annuarios Estatísticos do Brasil. Typographia da Estatistica, various years.

- Leão, E. A. d. (1931). Matte – Chá do Parana. Mundial.

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. The Free Press.

- Acervo Judiciário do Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro: Corte de Apelação (1888–1929), Juízo Especial do Comércio (1890–1922), Junta Comercial do Rio de Janeiro (1900–1914), Tribunal da Relação do Rio de Janeiro (1877–1891), Supremo Tribunal de Justiça (1875–1891), Supremo Tribunal Federal (1898–1919) and Tribunal Civil e Criminal do Brasil (1899–1910).

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431

- Albes, E. (1916). Yerba Mate – The tea of South America. G.P.O.

- Alchian, A. A., & Allen, W. R. (1977). Exchange and production: Competition, coordination and control. Wadsworth Pub Co.

- Alejandro, C. F. D. (1967). The Argentine Tariff, 1906-1940. Oxford Economic Papers, 19(1), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041041

- Alejandro, C. F. D. (1970). Essays on the economic history of the Argentine Republic. Yale University Press.

- Alexander, N., & Doherty, A. M. (2021). Overcoming institutional voids: Maisons Spéciales and the internationalisation of Proto-modern brands. Business History, 63(7), 1079–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2019.1675640

- Almanak Laemmert. (1904). 1442.

- Almanak Laemmert. (1909). 1146.

- Annuario Estatistico do Brasil: Economia e Finanças. (1917). Vol II. Typographia da Estatistica.

- Arquivo Municipal de Curitiba – Romario Martins Collection. (1921–1934).

- Associação Comercial do Paraná - Boletins da Associação Comercial. (1909–1919). Atas das Assembléias da Associação Comercial do Paraná.

- Bain, J. S. (1956). Barriers to new competition. Harvard University Press.

- Bayly, C. (2004). The birth of the global world 1780-1914: Global connections and comparisons. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Belfanti, C. M. (2018). Branding before the brand: Marks, imitations and counterfeits in pre-modern Europe. Business History, 60(8), 1127–1146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1282946

- Bently, L. (2008). The making of the modern trade mark law: The construction of the legal concept of trade mark, 1860-1880. In L. Bently, J. David, & J. C. Ginsburg (Eds.), Trade marks and brands – Interdisciplinary critique (pp. 3–41). Cambridge University Press.

- Bethell, L. (2018). Brazil: Essays on history and politics (Chapter 3). University of London.

- Boguszewski, J. H. (2007). Uma História Cultural da Erva-Mate: O Alimento e as Suas Representações [PhD dissertation, Universidade Federal do Paraná].

- Boletim da Propriedade Industrial. National Library. (1907–1909).

- Brazil National Exhibition. (1908, January-June). The South American Journal and the Brazil and River Plate Mail, 64, 53 [Baker Library Historical Collections. Harvard Business School].

- Bulmer-Thomas, V. (1994). The economic history of Latin America since independence. Cambridge University Press.

- Casson, M. (1994). Brands: Economic ideology and consumer society. In G. Jones & N. J. Morgan (Eds.), Adding value – Brands and marketing in food and drink (pp. 41–58). Routledge.

- Cervo, A. L., & Bueno, C. (2002). Historia da Política Exterior do Brasil. Editora da Universidade de Brasilia.

- Chamberlin, E. H. (1933/1962). The theory of monopolistic competition: A re- orientation of the theory of value. Harvard University Press.

- Chandler, A. D. (1959). The beginnings of “big business” in American industry. Business History Review, 33(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.2307/3111932

- Chandler, A. D. (1962). Strategy and structure – Chapters in the history of the American industrial enterprise. The MIT Press.

- Chandler, A. D. (1977). The visible and – The managerial revolution in American business. Harvard University Press.

- Chandler, A. D. (1990). Scale and scope: Dynamics of industrial capitalism. Harvard University Press.

- Chaves, M. d. L. M. (1995). Voltando ao Passado, Histórico de Determinadas Indústrias e Casas Comerciais de Curitiba. FIEP.

- Church, R. (2000). Advertising consumer goods in nineteenth century Britain: Reinterpretations. The Economic History Review, 53(4), 621–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.00172

- Clemens, M. A., & Williamson, J. G. (2001, December). Where did British foreign capital go? Policies, fundamentals and the Lucas paradox 1870-1913 [NBER Working Paper 8028]. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Coatsworth, J. H., & Williamson, J. G. (2002, June). The roots of Latin American protectionism: Looking before the great depression [NBER Working Paper 8999]. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Coatsworth, J. H., & Williamson, J. G. (2004). Always protectionist? Latin American tariffs from independence to great depression. Journal of Latin American Studies, 36(2), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X04007412

- Cohen, D. (1986). Trademark strategy. Journal of Marketing, 50(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251279

- Cohen, D. (1991). Trademark strategy revisited. Journal of Marketing, 55(3), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252147

- Comércio Exterior do Brasil, com os Paises de Maior Intercambio, 1842 – 1939. (1939–1940). Anuário Estatístico do Brasil - Repertório Estatístico do Brasil – Quadros Retropspectivos n°1. Serviço Gráfico do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.

- Companhia Exportadora de Mate do Parana. (1911, December 11). Projecto de Estatutos e Regulamento.

- Companhia Mate Laranjeira - Relatório à Primeira Assembleia Geral de 27 de Maio de 1893. (1893, Maio 25). Jornal do Commercio, 6.

- Companhia Mate Laranjeira – Relatório da Assembleia Geral de 30 Maio de 1896. (1896, Maio 29). Jornal do Commercio, 8–9.

- Companhia Mate Laranjeira - Relatório da Assembleia Geral de 31 Maio de 1900. (1900, Maio 30). Jornal do Commercio, 6.

- Companhia Mate Laranjeira. (1895, May 31). Relatório da Assembleia Geral.

- Companhia Matte Laranjeira. (1941). Panegírico de D. Francisco Mendes Gonçalves e sua Grande Obra, a Mate Laranjeira. Tip. Mercantil.

- Convenio entre la República Argentina y los Estados Unidos del Brasil sobre Marcas de Fábrica y de Comercio. (1901, October 30).

- Converse, L. A. (1940). Política Económica de la Yerba Mate. Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Corley, T. A. B. (1993). Marketing and business history, in theory and practice. In R. S. Tedlow & G. Jones (Eds.), The rise and fall of mass marketing (pp. 93–115). Routledge.

- Costa, S. G. d. (1995). A Erva Mate. Universidade Federal do Parana – Farol do Saber.

- Daniel, O. (2009). Erva-Mate: Sistema de Produção e Processamento Industrial. UFGD.

- Decree Law n° 1,236. (1904, September 24).

- Decree Law nº 16,264 (1923, December 19).

- Decree Law n° 2,682. (1875, October 23).

- Decree Law n° 2,682. (1975, October 23).

- Decree Law n° 248. (1870, April 22).