Introduction

The terms ‘knowledge economy’ and ‘knowledge capitalism’ have been used with increasing frequency since the 1990s as a way of describing the latest phase of capitalism in in the process of global restructuring. ‘Knowledge economy’ is often referred to as deep structural transformation of the economy caused by a technological revolution altering the production and transmission of knowledge (and information), leading to a shift to knowledge-intensive activities. Conceptually, this process of redefinition began with Drucker (Citation1969), Fritz Machlup, Daniel Bell and others who described nascent postindustrial tendencies towards increasing abstract, mathematical and symbolic processes that were part of an emerging and interlocking information technologies that constituted a new global algorithmic and data-driven knowledge architecture. These features comprised the ‘economics of knowledge’ that the OECD (Citation1996) synthesised and systematised around Romer’s (Citation1994) endogenous growth theory, Machlup’s (Citation1962) distribution studies, Porat’s (Citation1977) work on the information economy and various innovation studies of the science system (e.g., Gibbons et al., Citation1994; Lundvall & Johnson, Citation1994). Curiously, the OECD’s report did not refer to Gary Becker’s human capital or seek to integrate as part of the policy synthesis but human capital, after its first phase 1962–1992, also was very much part of the mix. The OECD’s report became the touchstone for policy in the era of the late 1990s and after.

The old liberal metanarratives of knowledge inherited from the Enlightenment based on high sounding knowledge ideals peeled away to reveal an economic discourse based on the calculated use of computing power, the significance of electronic networks, the efficiency and quality of knowledge, planning and progress in R&D, human capital theory, with increasing frequency in the use of these terms to describe the interface of new knowledge and technology, and a conception of technology-led science. Innovation, growth and productivity became instant key words and statements like ‘Knowledge is the engine of productivity and economic growth’ became the sloganised blanket legitimation for structural reforms for investments in public education and science that increased competition at the global level. This was a kind of unvarnished technological determinism thesis about technology-led development in the knowledge economy that eclipsed the agency of academics and concentrated power in the hands of knowledge managers and brokers.

The liberal humanist idea of the university began to shrivel up and die as languages, philosophy and other humanities departments were down-sized or closed down and MBA business and organisation studies flourished (up to the crash of 2007). These changes and the determined push for STEM subjects permanently altered the university curriculum, leaving the arts and humanities behind. The development of innovation capacity and the modernisation of IT infrastructure were seen as the necessary pillars of the knowledge economy with an emphasis on the speed of technological development and the development of technologies that were regarded as ‘knowledge generators’. In the discourse of the knowledge economy knowledge was commonly referred to as the main factor in production that focused on the intangibles, such as ideas and trademarks, networked through the rapid evolution of new digital communication technologies that made volume, storage and processing information possible at decreasing cost and created digital networks that formed the basis the internet. The discourse of knowledge economy, presented in in schematic and ideal terms, was presented as neutral, objective and inevitable – an aspect of Western-driven economic modernisation theory (Appendix). It was a progressive discourse that issued out of progress and ‘development’ studies that represented a kind of evolutionary sequence taught in universities.1 In actual fact, the discourse in the phase after the 1980s combined elements of neoliberalism on the one hand, especially New Public Management, and liberal internationalism especially on free trade, at least up until the point that Trump initiated the trade-tech wars with China.

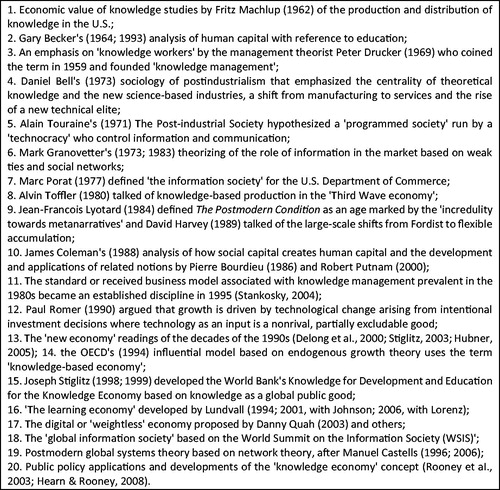

Figure 1. Interpretations and Genealogy of the Knowledge Economy. (Peters et al, Citation2009: pp. 2 and 3).

From knowledge capitalism to knowledge cultures and knowledge socialism

The term ‘knowledge capitalism’ was rarely used or referred to in the discourse of the knowledge economy. The first time the concept was used was by Alan Burton-Jones (Citation1999) Knowledge capitalism: Business, work, and learning in the new economy. This was a book at the beginning of the 2000s that revealed ‘how the emerging knowledge-based economy is redefining firms, empowering individuals and reshaping learning and work. It provided a practical tool-set for business managers to interpret and manage change’. In 2003 as the founding editor of Policy futures in education, I asked Burton-Jones (Citation2003) to write a piece with the title ‘Knowledge Capitalism: the new learning economy.’ His abstract reads

The increasing economic importance of knowledge is redefining firm–market boundaries, work arrangements and the links between education, work and learning. This article describes a framework for identifying organisational knowledge assets and learning needs, optimising knowledge supply and planning knowledge growth. The framework enables firms to improve their selection and deployment of internal and external knowledge resources and individuals to improve their career planning. It also assists learning institutions to tailor their products and services to the needs of individual and corporate knowledge consumers.

I started using the term soon after in a variety of publications working with Tina Besley and others but I was using it not as a term of approbation but as a disruptor, as a term that first historically situates knowledge economy as ‘knowledge capitalism’ in an info-tech digital capitalist late phase that signalled a profound structural transformation. Yet as I noted it was a conception that paradoxically contained within it also other radical open possibilities that also enhanced free knowledge exchange and approximate conditions of ‘knowledge socialism’ based on collaboration, sharing, collegiality and the peer economy, often in spite of the neoliberal university.

Impressed with Jean-Francois Lyotard’s (1984) arguments in The Postmodern Condition I began to flirt with the idea of ‘knowledge socialism’. For instance, in 2003 under the title ‘Post-structuralism and Marxism: Education as Knowledge Capitalism’ (Peters, Citation2003) I argued for ‘post-structural Marxism’ as the pedagogical practice of reading and rereading Marx in a critical manner and I briefly discussed the concept of the social in the post-modern condition before reviewing relations between post-structuralism and Marxism. Poststructuralist Marxism is not an oxymoron. It is simply another reading of Marx, developed under the model of Louis Althusser’s Reading Marx. I provided an account of Deleuze’s Marxism, using it to analyze education as a form of ‘knowledge capitalism’. I was using the term in an analytical way and contrasting it with an account I later christened ‘knowledge socialism’. Frankly, I did not understand those who wanted to christen Lyotard a ‘postmodernist’. To me it meant that they hadn’t read his work carefully – it wasn’t a celebration but rather a critique of capitalism in the post-modern condition (Peters, Citation1996, Citation2001).

In Building knowledge cultures: Education and development in the age of knowledge capitalism, working with Tina Besley (Peters & Besley, Citation2006), I developed the notion of ‘knowledge cultures’ as a basis for understanding the possibilities of education and development in the age of knowledge capitalism. ‘Knowledge cultures’, we argued, refers to the cultural preconditions in the new production of knowledge and their basis in shared practices, embodying preferred ways of doing things often developed over many generations. These practices also point to the way in which cultures develop different repertoires of representational and non-representational forms of knowing. We discussed knowledge cultures in relation to claims for the new economy, as well as ‘cultural economy’ and the politics of postmodernity. The book focuses on national policy constructions of the knowledge economy, ‘fast knowledge’ and the role of the so-called new pedagogy and social learning under these conditions. We concluded with a postscript – ‘freedom and knowledge cultures’ – commenting on the shift from a metaphysics of production to one of consumption and mentioned the emergence of a knowledge global commons as the basis for a global civil society as yet unborn. Here, we were attempting to realise in outline the development of knowledge cultures based on non-proprietary modes of production and exchange.

Somewhat later I tried to work up this idea in terms of the promise of creativity giving the concept a reading by reference to emerging form of openness in a book called Knowledge, science and knowledge capitalism (Peters, Citation2013a,Citationb) where I argued:

We live in the age of global science – but not, primarily, in the sense of ‘universal knowledge’ that has characterized the liberal metanarrative of ‘free’ science and the ‘free society’ since its early development in the Enlightenment. Today, an economic logic links science to national economic policy, while globalized multinational science dominates an environment where quality assurance replaces truth as the new regulative ideal. This book examines the nature of educational and science-based capitalism in its cybernetic, knowledge, algorithmic and bioinformational forms before turning to the emergence of the global science system and the promise of openness in the growth of international research collaboration, the development of the global knowledge commons and the rise of the open science economy. Education, Science and Knowledge Capitalism explores the nature of cognitive capitalism, the emerging mode of social production for public education and science and its promise for the democratization of knowledge.

Knowledge cultures was a fundamental concept that we developed in opposition to the dualism of the knowledge economy and knowledge society, and we fleshed out a critical concept that carried normative content by focusing on epistemological notion of ‘the community of inquiry’ drawing from Wittgenstein, Dewey and Pierce, that also implied an ethics of sharing and collaboration. It seemed to us that these philosophers provided the resources for a social reading of knowledge that was consistent with Marxist reading of knowledge as being based in a set of social relations. The pragmatist emphasis of the ‘community of inquiry’ and especially Pierce’s epistemology seemed to provide a warrant for investigating ‘knowledge socialism’ as a historical program.

In 2013, I founded the experimental multidisciplinary journal Knowledge Cultures, published three times a year to focus on knowledge futures (with Sean Sturm as the new Editor). The journal description is given in the homepage for the journal as:

Knowledge Cultures is a multidisciplinary journal that draws on the humanities and social sciences at the intersections of economics, philosophy, library science, international law, politics, cultural studies, literary studies, new technology studies, history, and education. The journal serves as a hothouse for research with a specific focus on how knowledge futures will help to define the shape of higher education in the twenty-first century. In particular, the journal is interested in general theoretical problems concerning information and knowledge production and exchange, including the globalization of higher education, the knowledge economy, the interface between publishing and academia, and the development of the intellectual commons with an accent on digital sustainability, commons-based production and exchange of information and culture, the development of learning and knowledge networks and emerging concepts of freedom, access and justice in the organization of knowledge production. (https://addletonacademicpublishers.com/about-kc)

The journal has carried special issues on the internationalisation of higher education, knowledge cultures, open science, cognitive capitalism, doctoral supervision, neuroscience, political economy of knowledge, creativity, globalisation, interculturalism, Marxism, aesthetics, Bakhtin, power and partnership, academic self-knowledge, curriculum studies, indigenous knowledge, open education and many others.

In early 2004, I coined the term ‘knowledge socialism’ in an editorial for a double issue on Marxism in the academy for the newly established journal of Policy Futures in Education (now a Sage journal with Mark Tesar as Editor). ‘Marxist Futures: knowledge socialism and the academy’ enquired into the unifying principle for identity politics:

There are expressions of new forms of socialism, for instance, that revolve around the international labour movement and invoke new imperialism struggles based on the movements of indigenous and racialised peoples. There are active social movements, perhaps less coherent but every bit as powerful as older class-based movements, such as the anti-capitalism, anti-globalisation movements, women’s and feminist movements, and environmental movements. (p. 436)

I went on to argue, if I am allowed a long passage that lays out the case:

One form of new expression concerns what I call knowledge socialism to indicate the new struggles surrounding the politics of knowledge that directly involve the academy and I do not mean simply refer to the role of theory. I am referring to what has been called knowledge in the age of ‘knowledge capitalism’, a debate that increasingly turns on the economics of knowledge, the communicative turn, and the emerging international knowledge system where the politics of knowledge and information dominates. One issue concerns intellectual property, not only copyright, patents and trademarks, but also the emergence of international regimes of intellectual property rights, and the accompanying emphasis on human capital and embedded knowledge processes that now drive university management.

I argued that issues of freedom and control are central to content, code and information and that the issue of freedom/control concerns the ideation and codification of knowledge and the new ‘soft’ technologies that take the notion of ‘practice’ as the new desideratum of new forms of social learning. The politics of the ‘learning economy’ and the economics of forgetting insists that new ideas have only a short shelf-life. I was not sanguine about the easy adoption and co-option of these forms that often advertise themselves in terms of reflection but really focus on efficiency and turning a profit. I noted that these questions are also tied up with larger questions concerning disciplinary versus informal knowledge, the formalisation of the disciplines, the development of the informal knowledge economy, and the pervasiveness of informal education. Informal knowledge and education based on free exchange is still a good model for global civil society in the age of knowledge capitalism (p. 436).

Invoking the short history of this academic journal I went on to argue that whatever the encroachment of knowledge capitalism on the universities and higher education more generally, the free and frank exchange of ideas based on the model of peer-review stills serves as a sound model of sociality and in this sense knowledge capitalism is parasitic on knowledge socialism for, as Marx, Wittgenstein and Bourdieu acknowledge, knowledge and the value of knowledge are rooted in social relations. I remarked ‘In this premise is buried the future politics of knowledge both for the academy and for the developing world’ (pp. 436–437).

In later paper, ‘Knowledge Socialism and Universities: Intellectual Commons and Opportunities for “Openness” in the 21st Century’ (Peters & Gietzen, Citation2012). I deliberately pitted the concept of knowledge socialism as an alternative to the currently dominant ‘knowledge capitalism’ explaining that whereas knowledge capitalism focuses on the economics of knowledge, emphasizing human capital development, intellectual property regimes, and efficiency and profit maximisation, knowledge socialism shifts emphasis towards recognition that knowledge and its value are ultimately rooted in social relations (Peters & Besley, Citation2006). Knowledge socialism promotes the sociality of knowledge by providing mechanisms for a truly free exchange of ideas enhanced by peer review. Unlike knowledge capitalism, which relies on exclusivity – and thus scarcity – to drive innovation, the socialist alternative recognises that exclusivity can also greatly limit innovation possibilities. Hence rather than relying only on the market to serve as a catalyst for knowledge creation, knowledge socialism marshals public and private financial and administrative resources to advance knowledge for the public good. The paper went on to argue that the university, as a key locus of knowledge creation, becomes – in Openness 3.0 and 4.0 models – the mechanism of multiple forms of social innovation, not merely in areas with obviously direct economic returns (such as techno-science), but also in those areas (such as information literacy) that facilitate indirect benefits not merely beholden to concern for short-term market gains. The paper put the case in this way:

Positioning the university in this way might seem overly idealistic, perhaps even disconnected from the tremendous financial realities facing universities, and higher education in general, in much of the world. Reactions of this sort, however, rely on the assumption that the current neoliberal model of higher education, with primacy placed on selling educational ‘products’ to ‘consumers’, is the best remedy to diminishing funding. Furthermore, although individual economic actors maximize personal benefits through their consumption choices, these choices frequently do not correspond to broader societal needs. Free exchange of knowledge in higher education, for instance, does more than provide economic returns to individual actors and institutions. Post-industrial nations, for example, can maximize their place in the global knowledge-based economy by collective, education-based, innovation. Perhaps more importantly, a broader and more social approach to higher education, both in terms of investment and return, provide better means for addressing truly wide-ranging problems such as climate change. The extent to which Openness 3.0, and therefore the Open University 3.0, are practicable remains unclear, but the technical affordances and social needs allow and demand an approach to higher education that moves beyond the limited models remain dominant.

By this stage, I had begun to examine concepts of openness as a basis for alternative knowledge practices and alternative conceptions of knowledge. I edited several books on the concept of openness and its connections with the ‘creative economy’ emphasising competing conceptions, the ‘mode of educational development’ and cognitive capitalism, focused on the question of digital labour (Araya & Peters, Citation2010; Peters & Bulut, Citation2011; Peters & Britez, Citation2008). At the basis of the argument, I wanted to explore arguments for an expressive conception of ‘creative labour’ as opposed ‘human capital’. In ‘Radical Openness: Towards a Theory of Co(labor)ation’ (Peters, Citation2014a,Citationb,Citationc,&Citationd) I examined the conceptual relations between ‘openness’ and ‘creativity’, creativity as the new development paradigm, and ‘creative labour’ as a way of beginning a discussion of ‘radical openness’ and its applications to institutions in the age of cognitive capitalism. The paper was the basis of a keynote presentation delivered to International Symposium on ‘The Creative University’ – a conference and book series I established in 2011 (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iZ5zb8gyAr4).

The concept of ‘radical openness’ is a concept that I coined as a result of a series of published articles and books on the concept of openness over a number of years. In particular, I had tried to rework what we called ‘the virtues of openness’ linking it to the development of scientific communication, the reinvention of the public good and the constitution of the global knowledge commons (Peters & Roberts Citation2011). We put the case, now old hat, for the creation of a new set of rights in a transformed global context of the ‘knowledge economy’, that is, universal rights to knowledge and education. In this perspective, we argued that education needs to be reconsidered as a global public good, with the struggle for equality at its centre. By charting various conceptual shifts, I had previously distinguished between three discourses of the ‘knowledge economy’: the ‘learning economy’, the ‘creative economy’, and the ‘open knowledge economy’, each with its specific conceptions of knowledge and economy (Peters, Citation2010). In the face of neoliberalism, privatisation of education and the monopolisation of knowledge, I argued that the last of these three conceptions – the open knowledge economy and the model of open knowledge production – offers a way of reclaiming knowledge as a public good and intellectual commons.

Over the past decade, I have explored the interrelationships between peer production, collective intelligence, collaboration and collective intelligence as a basis for a socialised academic knowledge knowledge (knowledge socialism) firmly anchored in a concept of creative labour (Peters, Citation2015; Peters & Heraud, Citation2015; Peters & Reveley, Citation2015; Peters & Jandric, 2015a,b; Peters & Jandrić, Citation2018). In particular, with a group of co-authors, I have tried to demonstrate that social innovation can co-create public goods and services by utilizing forms of collection intelligence (CI) and CI Internet-based platforms. Collective intelligence is a way new forms and ways of delivering public goods and services through forms of co-creation and co-production or peer production. This approach of collective intelligence, after Pierre A. Lévy (Peters, Citation2015) becomes an approach to the ‘creative university’ as the digital public university that is philosophically based on a concept of creative labour rather than human capital. The creative university is a concept that we have promoted through a series of conferences and books (Peters & Besley, Citation2013; see the seven volumes in the series at https://brill.com/view/serial/CREA).

On a more practical level, I founded The Editors’ Collective (http://editorscollective.org.nz/), now organised by Sonja Arndt, Marek Tesar and Andrew Gibbons, to engage in collective scholarship and collective writing. As the Mission records:

This editorial collective is based around the journal Educational Philosophy and Theory that sponsors the development of a journal ecosystem comprising several journals in order to: develop an experimental and innovative approach to academic publishing; explore the philosophy, history, political and legal background to academic publishing; build a groundwork to educate scholars regarding important contemporary issues in academic publishing; and encourage more equitable collaborations across journals and editors.

Together we have written several articles on academic publishing and peer review (Peters et al., Citation2016; Peters, Besley, & Arndt, Citation2019). The idea behind this research project with its different arms is to chart, develop and experiment with various forms of what I call knowledge socialism.

As of 2019, I am engaged in a project to edit a new collection with Tina Besley, Petar Jandric and Xudong Zhu as editors that takes seriously arguments for knowledge socialism and the rise of peer production as a means for the critical discussion of collegiality, collaboration and collective intelligence. We have invited a group of distinguished international scholars to contribute essays on the theme of the concept of knowledge socialism as a philosophical concept that has the power both to explain aspects of current knowledge practices but also certain contradictions in the structure and practice of knowledge capitalism.2 These essays are intended also to explore knowledge socialism as a programmatic concept, as a project, as a reality, and as a prescriptive concept. I hope that essays may explain knowledge socialism as an historical practice, as a part of knowledge capitalism, or, perhaps, as a complicit aspect of algorithmic capitalism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 See for example the Masters program at https://master-iesc-angers.com/towards-a-knowledge-economy/

2 Anyone interested in the project or in contributing should contact me at [email protected]

References

- Araya, D & Peters, M A. (Eds.) (2010). Education in the creative economy. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Burton-Jones, A. (1999). Knowledge capitalism: Business, work, and learning in the new economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burton-Jones, A. (2003) Knowledge capitalism: The new learning economy. Policy Futures in Education, 1 (1): 143–159. doi: 10.2304/pfie.2003.1.1.4

- Drucker, P. (1969). The age of discontinuity. Guidelines to our changing society. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary cocieties. London: Sage.

- Lundvall, B.-A., & Johnson, B. (1994). The learning economy. Journal of Industry Studies, 1(2), 23–42.

- Machlup, F. (1962). The production and distribution of knowledge in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- OECD (1996). The knowledge-based economy. Paris: The Organization.

- Peters, M. A., & Jandrić, P. (2018). Peer production and collective intelligence as the basis for the public digital university. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(13), 1271–1284. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2017.1421940

- Peters, M. A., Tina, B., & Sonja, A. (2019). Experimenting with academic subjectivity: Collective writing, peer production and collective intelligence. Open Review of Educational Research, 6(1), 25–39. doi: 10.1080/23265507.2018.1557072

- Peters, M A. (1996). (Eds.) Education and the postmodern condition. Foreword J-F Lyotard. Westport, CN.: Bergin & Garvey.

- Peters, M. A. (2001). Poststructuralism, marxism and neoliberalism: Between theory and politics. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Peters, M. A. (2003). Marxist futures: Knowledge socialism and the academy. Policy Futures in Education, 18(2), 115. doi: 10.2304/pfie.2004.2.3.1

- Peters, M. A. (2013a). The concept of radical openness and the new logic of the public. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(3), 239–242. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2013.774521

- Peters, M. A. (2013b). Radical openness: Creative institutions, creative labor and the logic of public organizations in cognitive capitalism. Knowledge Cultures, 1(2), 47–72.

- Peters, M. A. (2010). Three forms of the knowledge economy: Learning, creativity and openness. British Journal of Educational Studies, 58(1), 67–88. doi: 10.1080/00071000903516452

- Peters, M. A. (2014a). Competing conceptions of the creative university. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(7), 713–717. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2013.785074

- Peters, M. A. (2014b). Open science, philosophy and peer review. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(3), 215–219. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2013.781296

- Peters, M. A. (2014c). Openness and the intellectual commons. Open Review of Educational Research, 1(1), 1. doi: 10.1080/23265507.2014.984975

- Peters, M. A. (2014d). Radical openness: Towards a theory of co(labor)ation. In: Weber S., Göhlich M., Schröer A., & Schwarz J. (eds.). Organisation und das Neue. Organisation und Pädagogik (vol. 15). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Peters, M. A. (2015). Interview with Pierre A. Lévy, French philosopher of collective intelligence. Open Review of Educational Research, 2(1), 259–266. doi: 10.1080/23265507.2015.1084477

- Peters, M. A., & Besley, T. (2006). Building knowledge cultures: Education and development in the age of knowledge capitalism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Peters, M A., & Besley, T (Eds.) (2013). The creative university. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Peters, Michael A., Besley, Tina & Arndt, Sonja (2019). Experimenting with academic subjectivity: collective writing, peer production and collective intelligence. Open Review of Educational Research, 6:1, 25–39. doi: 10.1080/23265507.2018.1557072

- Peters, M A., & Britez, R. (Eds.) (2008). Open education and education for openness. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Peters, M. A., & Bulut, E. (Eds.) (2011). Cognitive capitalism, education and the question of digital labor. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Peters, M. A., & Heraud, R. (2015). Toward a political theory of social innovation: Collective intelligence and the co-creation of social goods. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 3(3), 7–23.

- Peters, M. A., & Gietzen, G. (2012). Knowledge socialism and universities: Intellectual commons and opportunities for ‘openness’ in the 21st Century. In R. Barnett (Ed.) The future university: Ideas and possibilities. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Peters, M. A., & Jandric, P. (2015a). Learning, creative col(labor)ation, and knowledge cultures. Review of Contemporary Philosophy, 14, 182–198.

- Peters, M. A., & Jandric, P. (2015b). Philosophy of education in the age of digital reason. Review of Contemporary Philosophy, 14, 162–181.

- Peters, M. A., Petar, J., Ruth, I., Kirsten, L., Nesta, D., Richard, H., & Leon, B. (2016). Towards a philosophy of academic publishing. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(14), 1401–1425. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2016.1240987

- Peters, M. A., & Reveley, J. (2015). Noosphere rising: Internet-based collective intelligence, creative labour, and social production. Thesis Eleven: Critical Theory and Historical Sociology, 130 (1), 3–21.

- Peters, M. A., & Roberts, P. (2011). The virtues of openness: Education, science and scholarship in a digital age. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Peters, M. A., Tze-Chang, L., & Oncerin, D. (2012). The pedagogy of the open society: Knowledge and the governance of higher education. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Peters, M. A., Marginson, S., & Murphy, P. (2009). Creativity and the global knowledge economy. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Porat, M. (1977). The information economy. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce.

- Romer, P. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8 (1): 3–22. doi: 10.1257/jep.8.1.3

Appendix

References for : Interpretations and Genealogy of the Knowledge Economy

From ‘Introduction: Knowledge Goods, the Primacy of Ideas and the Economics of Abundance’. In Peters, Tina, and Sonja (2009), Creativity and the Global Knowledge Economy. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Becker, G. (1964, 1993, 3rd ed.). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bell, D. (1973). The coming of post-industrial society a venture in social forecasting. New York: Basic Books.

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). ‘The Forms of Capital,’ Richard Nice (trans). In: J. F. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of theory of research for sociology of education (pp. 241–258), Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Castells, M. (1996, 2000, 2nd ed.). The rise of the network society: The information age: Economy, society and culture (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Coleman. J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94 (Supplement), 595-5120.

Bradford DeLong, J., & Summers, L. H. 2001. The 'new economy': background, historical perspective, questions, and speculations. Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, issue Q IV, 29–59.

Drucker, P. F. (1993). Post-capitalist society. New York, NY: Harper Business.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited, Sociological Theory, I, 201–233.

Hayek, F. (1937). Economics and knowledge. presidential address delivered before the London Economic Club, 10 November 1936; Reprinted in Economica IV (new ser., 1937), 33–54.

Hayek, F. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, XXXV(4), 519–530.

Hearn, G., & Rooney, D. (Eds). (2008). Knowledge policy: Challenges for the twenty first century. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Lundvall, B.-A., & Archibugi, D. (2001). The globalizing learning economy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lyotard,l-F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. (G. Bennington, B. Massumi, Trans.). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Quah, D. (2003a). Digital goods and the new economy. In Derek Jones, (Ed.), New economy handbook (pp. 289–321). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Academic Press Elsevier Science.

Quah, D. (1999). The weightless economy in economic development. CEP discussion paper; CEPDP0417 (417). London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy. 98, 71–102.

Rooney, D., Hearn, G., Mandeville, T., & Joseph, R. (2003). Public policy in knowledge-based economies: Foundation and Frameworks. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Stankosky, M. (2004). (Ed.) Creating the discipline of knowledge management: The latest in university research. London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Stiglitz, J. (1998). Towards a new paradigm for development: Strategies, policies and processes. Paper presented at the 9th Raul Prebisch Lecture delivered at tbe Palais des Nations, Geneva, UNCTAD, October 19, 1998.

Stiglitz, J. (1999a). Knowledge for development: Economic science, economic policy, and economic advice. Proceedings from the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics 1998. World Bank, Washington, DC: Keynote Address, pp. 9–58.

Toffler, A. (1980). The third wave. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Touraine, A. (1971) The post-industrial society: tomorrow's social history; classes conflicts & culture in the programmed society (L. Mayhew, Trans.). New York, NY: Random House.