Educational Philosophy and Theory (EPAT) had another successful year and I want to acknowledge all the help I received from the editorial team of Susanne Brighouse (Managing Editor), and Marek Tesar, Liz Jackson and Tina Besley (Deputy Editors). As I am fond of saying, like all journals EPAT is a collective enterprise depending on contributors, reviewers, readers and editors, as well as the production team at Routledge, Taylor and Francis. In this connection, I would like to take the opportunity to acknowledge and thank these different groups of people, and especially Alexandra Lazzari, Routledge’s Head of HSS International in Australasia, and Nigel King, who is our editorial manager on the production side. Along with the editorial team, both have really helped EPAT step up in the journal rankings: the 2018 Journal Citation Reports & Impact Factors by Web of Science, Clarivate, for EPAT has increased from 0.864 to 1.267. The journal now has a ranking of 149/243 in the Education & Educational Research subject category. In addition, the Citescore (Scopus) for 2019 was 1.49, including placements of #18/135 History and Philosophy of Science (a particularly pleasing result) and #296/1040 Social Science: Education. ‘So what?’ I hear you say and I am aware of the critique of performance and rankings having written them myself but this is a creditable result in the real world of academic capitalism which is due also to the Philosophy of Education Executive lead by Liz Jackson who have provided much support and inspiration. Like me they all know that while philosophy of education is declining as a university subject field with very few funded positions, the thirst for philosophy and theory in education and related fields increases rather than diminishes, if the growth and demand of EPAT are anything to go by. The rankings are a reflection of this, of our authors and their thinking, and of our readers too.

The journal received 253,219 article downloads in 2018, which is 86.5% higher than downloads received in 2017. 2019 is already demonstrating an increase of the same order of magnitude. Why is this the case? I entertain some fanciful thoughts that educators and educational philosophers understand that education is a fundamentally value-driven and theory-driven—some might say ethically-based—discipline. In my imagination, teachers and educational scholars feel deeply about their vocation and especially its public mission. These feelings, often only intuitions, appear to us as an activity that requires philosophy and philosophical understanding to interpret, legitimate and question connections with economy and with politics, whether capitalist or communist.

In my optimistic vein I think that educators are naturally drawn to theories of education, not just in terms of the latest research or methodology, but also in terms of ethics and the ‘public good’, even if neoliberal instrumentalities have tarnished the concept by rendering it as just another private satisfaction explainable by market transactions. Another day-dream I have regularly is about students, teachers, university lecturers and professors as ‘knowledge-gatherers’ (as Nietzsche would say) filled with human curiosity. The fact is that EPAT has gained more and more readers not only from the Anglo-American world but also from Europe and Asia. We have very few readers in Latin America and Africa. One of our aims is to reach out to readers and authors in these two continents. Another aim has been to try to dialogue with Chinese educational philosophers and scholars but this is not an easy or straightforward task but shifting to Beijing Normal University (BNU) has helped a great deal. Of course, the picture of international readership is more varied, nuanced and complex but we are committed to working at internationalizing the journal. It does not happen overnight! Some of the highlights from the publisher is provided below:

Highlights (from the Publishers’ Report, Taylor & Francis, 2019)

Your Journal received 253,219 article downloads in 2018, which is 86.5% higher than downloads received in 2017.

The most downloaded article is ‘Technological unemployment: Educating for the fourth industrial revolution’ by Michael A. Peters, with 7637 downloads.

The top Altmetric scoring article was ‘Peter Boghossian—What comes after postmodernism?’ by Peter Boghossian & James Lindsay, with a score of 170.

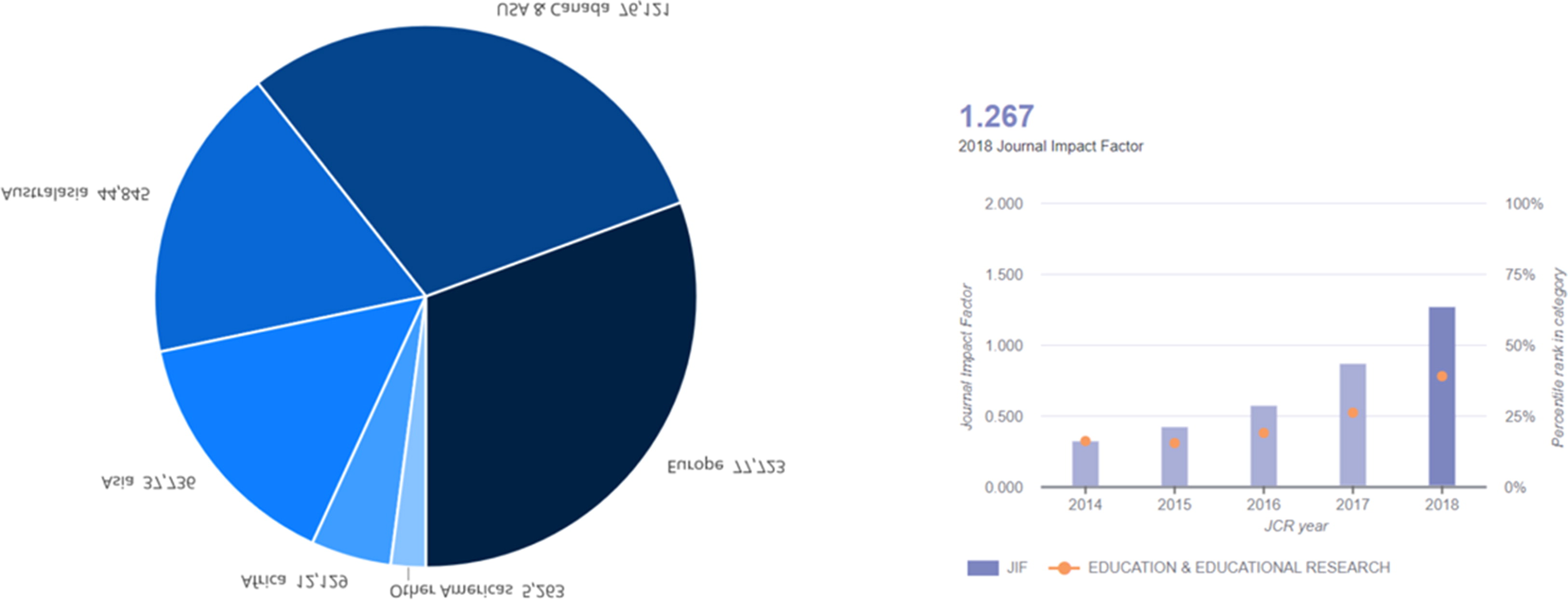

The journal’s 2018 Impact Factor is 1.267, ranking 149/243 in the [Education & Educational Research] JCR category.

There were 316 publications in 2018, some of which were Open Access.

Journal circulation 2,963 Institutions

Article download by region and Impact Factor

This year the journal is focusing on collective writing—the philosophy, methodology and pedagogy—as one of its major themes with an aim to develop experiments and new practices. It has progressed since the first collective article ‘Toward a Philosophy of Academic Publishing’ appeared in 2016. The abstract for that article reads:

This article is concerned with developing a philosophical approach to a number of significant changes to academic publishing, and specifically the global journal knowledge system wrought by a range of new digital technologies that herald the third age of the journal as an electronic, interactive and mixed-media form of scientific communication. The paper emerges from an Editors’ Collective, a small New Zealand-based organisation comprised of editors and reviewers of academic journals mostly in the fields of education and philosophy. The paper is the result of a collective writing process. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00131857.2016.1240987.

We have completed several articles on collective writing (http://editorscollective.org.nz/) and there are several collective writing examples in progress—on video ethics for research on children, photovideo methodology, philosophy of education and collective writing as pedagogy.

This year we will also launch the new PESAgora an OA journal that incorporates ACCESS. Thanks to Tina Besley and Marek Tesar for digitizing the entire digital archive, a mammoth task given that the journal stretches back to the early 1980s when Jim Marshall, Colin Lankshear and I established it. It is a useful archive to explore since it provides excellent work by a group of radical scholars in the Education Faculty at Auckland during the periods that Jim Marshall, Roger Dale and John Hattie were the acting Deans. It was a department of surprises: besides Jim and Roger, also Eve Coxon, Alison Jones, Susan Robertson, Peter Roberts, Linda and Graham Smith, Leonie Pihama, Kuni Jenkins and members of various Maori research units and institutes, and many others. The group of PhD students in philosophy of education in the 1980s were exceptional—Nesta Devine, Patrick Fitzsimmons, Ruth Irwin, Peter Fitzsimmons, Sandy Farquar, Sharon Harvey and others.

PESAgora will incorporates ACCESS: Critical Perspectives on Communication, Cultural and Policy StudiesFootnote1 and will provide both an archive and a repository but also an opportunity to further develop the journal under new editorship. PESAgora is an Open Access meeting place for those interested in educational philosophy and theory as encompassing a broad sweep and the intersections of education, philosophy, technology, indigenous and identity issues, and the environment. It is interested in philosophical and theoretical approaches to contemporary politics, economy and society. A rather wide brief but we need diversity and there is no attempt to provide a systematic analysis.

Agora is derived from the ancient Agora of Athens which was a place of artistic, spiritual and political life where citizens could gather to speak in public. The Agora of Athens was where Socrates held court to anyone who would listen, questioning them on the meaning of life and where Socrates attracted a young poet Aristocles, who was to become Plato. The Agora served as an early model for both the Academy and the dialogues. It evolved as a public space in Hellenistic and Roman Greece in c. 323BC–267AD.

PESAgora will provide comments on issues and concerns related to philosophy of education, news about other professional events and conferences. It combines different features including Ideas (500 words or less), Essays (2000 words), Replies, Academic Columns, Photos, Social Media and News with alerts to Educational Philosophy and Theory (EPAT) articles and editorials, special issues and papers.

We are now ready to appoint an Agora Editorial Team comprising of Web Related Editorial paid positions:

A Content Manager/Assistant Editor: the person who processes and publishes content on the website. This involves processing pre-existing and new articles into a format suitable for the web. It will be very helpful if this person has access to a recent copy of Adobe Acrobat Pro DC and Microsoft Word.

Social Media and Communications Manager: the person to run the Facebook and Twitter page and manages email campaigns.

Administrator: the person who handles the email account.

(Anyone interested in joining the editing team please send a short one-page CVV and contact: The Editor PESAgora, [email protected]).

We will also be recruiting columnists to write ‘columns’ (rather than blogs) on specified themes. We already have a great team and we will be building it with columnists on higher education, Chinese education, indigenous education, feminism, identity politics, so on. My thanks to the Editorial Team in 2019—Marek Tesar, Liz Jackson, Tina Besley and Susanne Bridghouse; all the reviewers for 2019; and the contributors. 2020 looks a promising year for EPAT.

2019 was a ‘disruptive’ year. Some would argue it was a watershed year for environment, politics, trade, migration and education and science. It was an exceptional year in an exceptional decade with many breakthroughs in science and technology. Yet 2020 and the next decade promise to be tumultuous with the economic and political climate fraught with a range of difficulties impacting on the global context and framework within which education and science take place. There are many problems that face humanity. Some of these can be represented in some disturbing trends:

The continued rise of national populism.

Increases in far-right and white supremacism.

Immigration and refugees political regimes.

Strong-man authoritarian politics.

Shift from left to right in South America.

End of liberal internationalism.

Problems in Turkey and ongoing wars in Syrian and Yemen.

US elections—Trumpalism?

Questioning the legitimacy of the democratic market system.

The continued rise of state capitalism.

Growth slow-down—China’s economy growth slowest in 30 years.

Impending/possible global financial crisis (Mk II) with historically low interest rates.

Growing social unrest over equality (UK top 10% own more than 50%).

The growing tensions over the future direction of the euro.

The next phase of the US–China trade-tech war.

The shift from oil/gas/coal to sustainable energy and economy.

Development of new energy regimes based on solar, wind, wave power.

Environmental ‘catastrophe’ looming—climate warming (e.g. Australian bushfires).

Rapid species depletion, desertification, deforestation (e.g. Amazon), disposal of waste.

Water and air pollution.

Rise of populist Green parties and the new green economy

Chinese foreign policy—HK (riots), Taiwan (anti-Chinese election), Tibet.

China’s mounting debt.

The Huawei security debate, 5G and 6G developments.

Chinese students turning away from US universities.

Made in China 2025 priorities—AI, IoE, blockchain in supply lines.

Political effects of 70+ member states of BRI.

Growth of Sino-Russian axis (The Belt).

China’s emergence as global power with alternative architecture for world institutions.

Information wars, post-truth and fake news.

The development of two separate parallel technology systems.

Politicizing of social media and manipulation of democracy.

Growth on international terrorism DarkNet.

Growth of AI and civil intelligence security systems including facial recognition.

Increasing technology-led developments in education and science.

Science Brexit and difficulties for US science under Trump.

New problems for international education.

Development of academic precariat.

Crunch time for climate science and biodiversity research.

Political influences in science and higher education (Brexit fallout).

AI inroads on research and platform education.

‘Innovation’ ideology and ‘schools of the future’.

Twitter and Facebook education.

Continuing Neoliberal reform and privatisation policies.

This is just a list of the obvious possibilities and we are talking about ‘complexity’ where causal factors involve cross-pollination. These are some of the main changes that might influence the shape of the next decade. Why should philosophy of education become aware of these possible conditions? How can a little field influence developments?

In a BBC ‘Culture’ report Nel Armstrong investigates ‘Why philosophers could be the ones to transform your 2020’ noting that ‘Long-dead thinkers from Socrates to Nietzsche are the latest hot property when it comes to self-help books.’ He suggests that the latest trend in publishing positions philosophers as self-help gurus. He writes:

Last autumn saw the publication of Lessons in Stoicism by John Sellars, which aims to show how we can benefit from thinking like the ancient Stoics; and How To Be An Existentialist by Gary Cox, a ‘genuine self-help book offering clear advice on how to live according to the principles of existentialism formulated by Nietzsche, Sartre, Camus, and the other great existentialist philosophers’. Then there was How To Teach Philosophy To Your Dog: A Quirky Introduction to the Big Questions in Philosophy by Anthony McGowan, which begins by suggesting that studying philosophy ‘may empower you to become a better person’, and ends by considering the meaning of life.

Meanwhile the recently-published An Ethical Guidebook to the Zombie Apocalypse by Bryan Hall, imagines a Walking Dead-type scenario as a means to introduce the reader to some of the key moral dilemmas explored by thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Kant. Then next week comes How to be a Failure and Still Live Well by Beverley Clack, which draws upon philosophy and theology to consider how failure can help you to live a good life. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20200114-why-philosophers-could-be-the-ones-to-transform-your-2020

He cites Angie Hobbs, Professor of the Public Understanding of Philosophy, University of Sheffield, who believes it is because we are at such a global crisis point:

At the moment, again we’ve got people seeing the world in extreme flux—financially, geo-politically, with regard to climate change. Is liberal democracy going to survive? Is the planet going to survive? There are really huge worrying questions. People are looking for a guide through these very uncertain times.

But these questions are not to be answered by an individualistic positive psychology that teaches us mindfulness techniques when the rest of the world is going to hell in a basket. Rather we need a philosophy that responds to the future of humanity and tackles global issues in a collective and intercultural way. With many of these problems education is a good place to start.

Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

[email protected]

Notes

1 The preview website can be accessed here: https://pesaagora.com?preview. The basic site has been built to match the mock-ups with articles added to the Essay category. A CFP and event have been added also, and an example promotion (for the PESA conference) appears above the footer on all non-homepage pages.