Open Peer Review: Educational Philosophy and Theory (EPAT)

Michael A. Peters, Beijing Normal University, PR China

In 2016 EPAT started experimenting with open peer review for articles that were part of collective writing projects. The first article was ‘Toward a Philosophy of Academic Publishing’ (Peters et al., Citation2016) that emerged from The Editors’ Collective based around the development of a journal ecosystem comprising a number of journals in order to:

develop an experimental and innovative approach to academic publishing;

explore the philosophy, history, political and legal background to academic publishing;

build a groundwork to educate scholars regarding important contemporary issues in academic publishing; and,

encourage more equitable collaborations across journals and editors.

Part of this process also aimed at experimenting with collective writing, re-examining expert peer review, and romoting greater recognition and discussion of academic subjectivity in the process of academic writing.

EPAT follows a strict anonymous double-blind peer review system for all 150 articles annually submitted with the exception of a small number of articles that are part of collective writing projects for which EPAT uses an open review system and are presented as ‘EPAT Collective Writing Project’ or PESA Executive Collective Writing Project’.

EPAT initiated collective writing projects from 2016 and now supports several such article series including:

Philosophy in a New Key (early 2020)

Forms of Post-Marxism (new, October 2020)

Others articles as specified

Collective writing normally involves several authors who, in relation to a structured theme, write 500 words that are edited as one article with a common set of references. These articles are open reviewed most often by the editors and sometimes by invitation of experts.

Open peer review has emerged in recent years as a modification of the scholarly review system that supports: (i) open identities where authors and reviewers become aware of each other’s identity; (ii) open reports, where review reports are published alongside the relevant article rather than being kept confidential; (iii) open participation, where ‘the wider community (and not just invited reviewers) are able to contribute to the review process’ (‘Open peer review,’ 2020).

JMIR publications suggest that ‘open peer review’ (OPR) has two meanings: (i) transparency – that ‘peer reviewers who participate in the peer review process are not anonymous’; (ii) participation – ‘open community peer-review’ (OCPR), ‘open peer review is open to anybody who wishes to participate’ (JMIR Publications, Citation2020). There is emerging consensus that OPR based is on openness and transparency that are considered core values of science (Morey et al., Citation2016).

Now many journals support open peer review including BMJ, BioMed Central, Nature, and PLOS. Sometimes the entire pre-publication history of the article is published online. Such innovations are part of the dissatisfaction with expert peer review and also the experimentation of new innovation practices that have become part of open science and open education. Nature Neuroscience (Citation1999) reported that the British Medical Journal embraced open review on ethical grounds based on the argument as then editor Richard Smith that ‘a court with an unidentified judge makes us think immediately of totalitarian states and the world of Franz Kafka’. This report now twenty years old also indicates the problems with peer review, including systematic biased of referees, against younger and female scholars. Yet the report also argues that some of the arguments against the effectiveness of peer review are misplaced.

In one study, Ross-Hellauer (Citation2017) mentions the following problems with traditional peer review:

Unreliable and inconsistent: Reviewers rarely agree with one another. Decisions to reject or accept a paper are not consistent. Papers have been known to be published but then rejected when resubmitted to the same journal later.

Publication delays and costs: At times, the traditional peer review process can delay publication of an article for a year or more. When ‘time is money’, and research opportunities must be taken advantage of, this delay can be a huge cost to the researcher.

No accountability: Because of anonymity, reviewers can be biased, have conflicts of interest, or purposely give a bad review (or even a stellar review) because of some personal agenda.

Biases: Although they should remain impartial, reviewers have biases based on sex, nationality, language or other characteristics of the author(s). They can also be biased against the study subject or new methods of research.

No incentives: In most countries, reviewers volunteer their time. Some feel that this is part of their job as a scholar; however, others might feel unappreciated for their time and talent. This might have an impact on the reviewer’s incentive to perform.

Wasted information: Discussions between editors and reviewers or between reviewers and authors are often valuable information for younger researchers. It can help provide them with guidelines for the publishing process. Unfortunately, this information is never passed on (‘What is open peer review?’, 2020).

Ross-Hellauer and Görögh (Citation2019) indicate that

Open peer review (OPR) is moving into the mainstream, but it is often poorly understood, and surveys of researcher attitudes show important barriers to implementation. As more journals move to implement and experiment with the myriad of innovations covered by this term, there is a clear need for best practice guidelines to guide implementation.

They provide a review of the various traits of open peer review are proposed to address, including accountability, bias, inconsistency, time, incentive and wasted effort (see Foster Open Science, Citation2020).

The use of OPR in EPAT is not based on arguing that OPR is better than blind peer review (BPR). EPAT employs both methods. It relies on BPR for 90 percent of its articles but employs OPR for its collective writing projects for many of the reasons cited above. In addition, we would argue that OPR complements the process of collective writing where there are often more than ten or as many as twenty authors pursuing a structured and curated theme organised by lead authors. Open reviewers tend to be expert scholars who are invited to comment on the thematic contributions (500–700 words) and to extend and develop the arguments involved, as well as indicate further avenues for research. They are also permitted to be critical and constructive, and the results are further reviewed by the editors. This is an innovation for EPAT that the editors have experimented with in the last couple of years, refining the process as we go. I believe that the OPR, as we now practised it, is important in a non-empirical field like educational philosophy and theory where there is no data or experiments to be evaluated but is often based on argument or narrative or textual analysis where ‘validity’ and ‘objectivity’ have less obvious application than in science. Arguably, the form of collective writing also enables a summative analysis of themes in 500–700 words that help to clarify, expand, or suggest alternative thinking. Openness is a key value for EPAT and is designed to support transparency, to assist authors in interactions with the editors and other contributors, and to encourage collective or collaborative academic practices in enriching the literature, in providing an alternative to ‘industrial’ forms of publishing that support the author, to support and mentor younger scholars in understanding the process of review, to improve the quality of constructive feedback, and to support the ‘open’ movement in scholarly communication.

Open peer review from a managing editor’s viewpoint

Susanne Brighouse

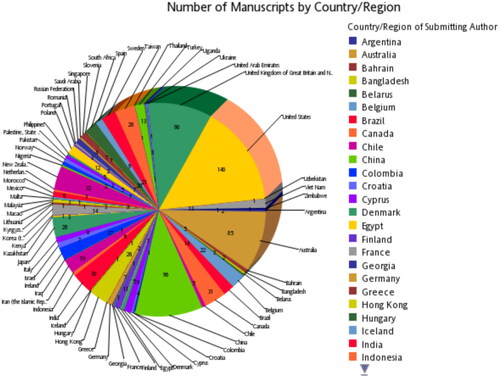

I have been the managing editor for Educational Philosophy and Theory, (EPAT) for over fifteen years. The journal is now a vastly different publication from the minor publication it was when I began in this role. Over the last two years, (2019 and 2020), we have had 614 original submissions, 311 revisions submitted bringing the total of 925 manuscripts needing to be reviewed. EPAT is now a truly international journal with submissions from at least 80 different countries. The largest number coming from the USA, the UK, Australia, China, New Zealand and Sweden. But there are many contributions from South America, Western and Eastern Europe, Canada and from many nations of the Middle East, Central Asia, the African continent, and the East, from Singapore to Japan, including India and Indonesia.

Finding reviewers is now a major task and, although EPAT has a large database of expert reviewers, the significant disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic means many of them have large workloads and are unable to review as often as requested. As EPAT experiments with the more open review systems that Michael Peters has explained in the introduction, it will be interesting to see if this takes some of the pressure off reviewers without reducing the quality of scholarship. Open Peer Review (OPR) is becoming more mainstream and this seems to be what scholars are asking for as in the Editorial Nature (Citation2020) we read that in a, ‘2017 survey of Nature referees, 82% agreed that standard peer review ensures high-quality work gets published. But 63% said publishers should experiment with alternative models, and more than half said peer review could be more transparent – and expected publishers to do more to make it so’.

In my experience, there are some disadvantages to traditional blind reviewing. Some reviewers do not give a thorough reason for their response, possibly because of time constraints, but, as they are protected by anonymity, they have nothing to lose by being very brief and dismissive when perhaps authors deserve a little more help to improve their scholarship. For most submissions, EPAT uses two blind reviewers and they may give quite different responses, one rejecting a paper while the other accepts it with minor changes. This can mean time is lost finding a third reviewer or the editor must take time be a third reviewer and then to explain to the author the decision. Editorial decisions in such cases can be difficult if responses are very brief. If they were not anonymous, more reviewers might take more time and care with responses. Most EPAT reviewers have had a European cultural background, and if the author is blinded, reviewers may have no knowledge of their ethnicity or cultural background. With the diverse background of authors, reviewers may be looking at the scholarship through a quite different lens than that of the author. In these cases, unconscious biases may emerge in the reviewing process. As with reviewing work from authors of varying genders and ages.

There may be disadvantages in a fully open review process and these experiments of EPAT are a good way to start to move towards a more open review system. Disadvantages of the OPR can be for example, when a well-known and highly esteemed author submits, a reviewer knowing their reputation may feel disinclined to be too critical. I have seen examples when such scholars have submitted an article and have not put the attention to details that such an article may require, and reviewers have made strong comments about this. Are they going to do this if the author is known to be a highly respected scholar? How will authors react when they know the names of reviewers who have given them an extremely critical response.

If the reviewing process is open, with readers able to see all of it, at least in the online publications, less experienced scholars may learn how to improve their own submissions. Such publications would require changes in the online publishing platform but in time this would be able to be done as publishers are asked to move to the more open review process.

With the need for expert reviewers growing, EPAT introduced a mentoring system for new reviewers, the Editorial Internship Group (EIG) with a view to support and mentor younger scholars. Interns were sent a manuscript, and they used an online chat group to share comments. A final review from these comments was then written by an experienced reviewer.

With either the blind or open system of reviewing, a journal’s reputation is dependent on the high quality of reviewing. EPAT is lucky to have many such reviewers who give of their valuable time.

On the importance of open peer reviews

Marek Tesar, The University of Auckland

The review process has been long-termly beneficial to guiding the academic field, shaping the disciplines and advancing knowledge; particularly through the process of blind peer reviews which aims to maintain objective outcomes and opportunities for all involved (Tesar 2020). As such, blind peer review is extremely beneficial, particularly in the natural sciences where control and bias are important to manage. However, questions are often raised about whether in humanities (and to a lesser extent the social sciences) the same concerns are applied.

Scholarly communities have witnessed a lot of critique over the blind peer review process. Anonymity has allowed a perpetuated push of academic ideologies, sometimes silencing ideas that are different or progressive. It was not uncommon that the very issues that they were trying to wipe out, such as racism, misogyny and academic bullying or the flexing academic muscles under academic work, under the pretence of anonymity, have been escalated because of that anonymity, including requests in revisions for a particular work to be cited, changing the narrative. This has been particular evident when editors would not intervene and let these type of reviews slip through to the authors.

Academic collegiality and a lack of constructive criticism are some of the concerns that are critical to address in blind peer reviews. Blind peer reviews are often done not by experts in the field, as they lack the time or motivation to do them, and the narratives of editors and editorial management teams choosing reviewers are becoming common narratives in Academia. In some journals, the blind peer review is conducted via an editor asking the author to submit names of recommended reviewers. Some of these concerns – and its underlying conditions – were discussed in recent writing, for example, by Peters, Arndt, et al. (Citation2020) and Stewart (Citation2017). Of course, these ideas cannot be separated from the neoliberal condition of Academia, the conceptualisation of what counts in academic progression, and what is needed to be done. Gone are the times of the old days when being asked to be a reviewer was exciting and a privilege. Now it is one of the tasks that falls down the priority order of a busy academic.

There is merit in examining the intersections of philosophy, education and methodology, whether it is in research or publishing, or academic peer review. It has been argued that open reviews are mitigating some of these concerns. Open reviewers, who are usually senior scholars, write a review, which is then published. There is fairness and feedback associated with them, as they contribute to shaping of the argument. There is a feeling of being part of a collective. Some recent exciting work has utilised open reviews (see, for instance, Jandrić, Citation2020; Peters, Rizvi, et al., Citation2020). There are times when blind peer reviews are much needed, and research demands that attention to generation of new knowledge extending across the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences. In the field of the philosophy of education where we advocate for openness, for freedom of expression, for collaboration, and for intellectual connections it makes a lot of sense not to subscribe to just one way for how to address this.

Beyond critique is machinic creation: open peer review as assemblage

Sean Sturm, University of Auckland

Open peer review (OPR) has historically been undertaken by scientific journals to ensure transparency in research and research dissemination via ‘complete openness to a distinct community or the public’ (Ford, Citation2013, p. 314). OPR in the collective writing exercises of the Editors’ Collective and authors in its ambit has worked rather differently. It has involved a three-phase process: the ‘lead author’ writes a provocation on a topic; several authors are invited to respond to the provocation as they see fit; and 2–3 reviewers are invited to respond to the collated contributions. The OPR process has allowed for a kind of response to the contributions of authors that differs from the ‘normal’ peer review process in two ways. First, it enables the reviewer to respond to them collectively, that is, as a body of contributions (of which the reviewer’s contribution is one), more than as individual contributions. Second, the OPR process enables the reviewer to respond to them additively, by focussing not so much on what the contributions did not say as on what they could be saying. What results from the process of OPR is thus a synergistic assemblage, a creative machine that works against the individualising and normalising drives of the normal peer review process whereby disciplines initiate their ‘disciples’… over and over (see Trafimow & Rice, Citation2009).

As such, OPR fits with the concept of collective writing as ‘composition’ (Wyatt et al., Citation2011, after Deleuze, Citation1992) that I have sketched elsewhere (Peters, Arndt, et al., Citation2020). It opens up writing as a diagrammatic play of forces by multiplying, transforming and redistributing the relations of authors, messages and readers that constitute the centres of power in writing. As I see it, as an open reviewer, I serve not as anonymous and disciplinary reader of the authors’ contributions, but as co-author, or ‘composer’, albeit once the other authors have made their contributions. And I can recruit other-than-human ‘readers’ such as software applications to be composers, as I did in my response to ‘Philosophy in a New Key’ (Peters, Oladele, et al., Citation2020) by mapping the locations of contributors with Mapcustomizer or the frequency of humanist vocabulary in the contributions with nVivo. I cannot deny that my (or our) responses were critical in intent – just not in the same way as they might be in a normal peer review. By admitting other-than-human ‘readers’, I hoped to address the unlocated and anthropocentric nature of the collated contributions by locating them and allowing other-than-humans to add their contribution as ‘authors’ to the collective. In a sense, my (or our) response thus spoke not to the merits or otherwise of the contributions of individual authors but to the individualising and normalising drives of the discipline. It also spoke to what the contributions could have said if they worked together or, rather, could be saying if they can function as a synergistic assemblage. Beyond critique (pace Latour, Citation2004 and Felski, Citation2011) is machinic creation.

The education of open peer-reviewing

Liz Jackson, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

While some argue that regular peer review practices can result in needless humiliation (Comer & Schwartz, Citation2014), open peer review can better exemplify the values of peer review as a form of pedagogy (Jackson et al., Citation2018). As a form of pedagogy, peer-reviewing can be educational and instructive to both reviewers and authors. First, open peer review reveals and underscores the way in which reviewers and authors are both ideally contributing to knowledge production through their actions by shaping an article. Open peer review as a publication practice further illuminates how research is essentially an act of opening a topic and field to new extended conversation, while the practices of review at the same time play a crucial role in assessing quality of information and claims.

Questioning is one aspect of review. Within an open process questioning goes beyond prompting reflection by an author, to enhance thinking for all involved: peer reviewers, authors, and editors. Through peer review, a questioning way of thinking becomes apparent, as a community ‘gathers’ around a given field of inquiry. If one thinks about an academic article as like a work of art, Heidegger’s (Citation1999) thesis on art provides further insight: ‘the work erects a world, which in turn opens a space for man and things’ (p. 141). The gathering of scholars discloses a world as an article comes into being, offering space for others, across times and place, to also join in Grierson (Citation2008). This field can, however, can disappear from view when peer review is a closed act, as if a paper reflects only one single solitary person’s ideas, within one moment of time.

One of the concerns of anonymous peer reviewing is that a reviewer can lose sight of care and trust within their role, overlooking their duty, perhaps sometimes unintentionally, to act in the best interests of an author and of a scholarly field (Jackson et al., 2018). In such cases, an author is more likely to be affronted by reviewers’ comments, casting the whole process as negative. In open peer-reviewing, this situation is far less likely to happen, as people are confronted with one another as persons, making the charge and commitment to treat each other and the process in an educational and constructive matter more apparent and realisable.

To be a competent reviewer demands knowledge. To see what is good in a manuscript, to acknowledge the time and effort of authors, to thoughtfully describe its flaws and ways forward, are also critical skills of quality peer reviewing (Stewart, Citation2016). For junior academics, peer-reviewing for journals improves writing skills and proficiency via exposure to more research, and also helps cultivate meaningful connections with new fellow colleagues (Jackson et al., 2018). Open peer review can encourage the best of peer-reviewing in this case despite the energy required, as it enables self-regulatory reflective understanding on reviewers’ parts, particularly enabling junior scholars to learn from other peer reviewers and to identify their review work as part of a contribution to a community of scholarship. It can also build meaningful connections between junior authors and more experienced reviewers, as an act more similar to co-authorship, that connects previously separate scholars for one process of knowledge production.

Beijing Normal University, PR China

[email protected]

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael A Peters

Michael A. Peters is the Editor-in-Chief of Educational Philosophy and Theory, Susanne Brighouse is Managing Editor, Marek Tesar and Liz Jackson, are Deputy Editors and Sean Sturm is Reviews Editor. This article is a discussion of the process of Open Peer Review as we have developed it in order to assess and provide constructive criticism of Collective Writing projects (CWP), another new development for EPAT. CWP that provides an alternative collective form of the article offers the opportunity to include five or more contributing authors each of whom writes five hundred words (a kind of extended abstract) according to a structured thematic project. CWP demands a new form of peer review that both assess and adds to the collective article.

References

- Comer, D. R., & Schwartz, M. (2014). The problem of humiliation in peer review. Ethics & Education, 9(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2014.913341

- Deleuze, G. (1992). Expressionism in philosophy: Spinoza (M. Joughin, Trans.). Zone Books.

- Editorial Nature. (2020). Nature will publish peer review reports as a trial. Nature, 578, 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00309-9.

- Felski, R. (2011). Critique and the hermeneutics of suspicion. M/C Journal, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.431

- Ford, E. (2013). Defining and characterising open peer review: A review of the literature. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 44(4), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.44-4-001

- Foster Open Science. (2020). ‘Open peer review.’ https://www.fosteropenscience.eu/learning/open-peer-review/#/id/5a17e150c2af651d1e3b1bce

- Grierson, E. M. (2008). Heeding Heidegger’s way: Questions of the work of art. In V. Karalis (Ed.), Heidegger and the aesthetics of living (pp. 45–64).Cambridge Scholars.

- Heidegger, M. (1999). The origin of the work of art. In D. Krell (Ed.), Basic writings: Martin Heidegger (pp. 139–212). Routledge.

- Jackson, L., Peters, M. A., Benade, L., Devine, N., Arndt, S., Forster, D., Gibbons, A., Grierson, E., Jandrić, P., Lazaroiu, G., Locke, K., Mihaila, R., Stewart, G., Tesar, M., Roberts, P., & Ozoliņš, J. (J.). (2018). Is peer review in academic publishing still working? Open Review of Educational Research, 5(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2018.1479139

- Jandrić, P., Hayes, D., Truelove, I., Levinson, P., Mayo, P., Ryberg, T., Monzó, L. D., Allen, Q., Stewart, P. A., Carr, P. R., Jackson, L., Bridges, S., Escaño, C., Grauslund, D., Mañero, J., Lukoko, H. O., Bryant, P., Fuentes-Martinez, A., Gibbons, A., … Hayes, S. (2020). Teaching in the age of Covid-19. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 1069–1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00169-6

- JMIR Publications. (2020). What is open peer-review? https://support.jmir.org/hc/en-us/articles/115001908868-What-is-open-peer-review-

- Latour, B. (2004). Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern. Critical Inquiry, 30(2), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/421123

- Morey, R. D., Chambers, C. D., Etchells, P. J., Harris, C. R., Hoekstra, R., Lakens, D., Lewandowsky, S., Morey, C. C., Newman, D. P., Schönbrodt, F. D., Vanpaemel, W., Wagenmakers, E.-J., & Zwaan, R. A. (2016). The peer reviewers' openness initiative: Incentivizing open research practices through peer review. Royal Society Open Science, 3(1), 150547. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150547

- Nature Neuroscience. (1999). Pros and cons of open peer review. Nature Neuroscience, 2, 197–198. https://doi.org/10.1038/6295

- Nature will publish peer review reports as a trial. (2020). Nature, 578, 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00309-9

- ‘Open peer review.’ (2020a). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_peer_review

- Peters, M. A., Arndt, S., Tesar, M., Jackson, L., Hung, R., Mika, C., Ozolins, J. T., Teschers, C., Orchard, J., Buchanan, R., Madjar, A., Novak, R., Besley, T., Sturm, S., Roberts, P. & Gibbons, A. (2020). Philosophy of education in a new key: A collective project of the PESA Executive. Educational Philosophy and Theory. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1759194

- Peters, M. A., Jandrić, P., Irwin, R., Locke, K., Devine, N., Heraud, R., Gibbons, A., Besley, C., White, J., Forster, D., Jackson, L., Grierson, E., Mika, C., Stewart, G., Tesar, M., Brighouse, S., Arndt, S., Lazaroiu, G., Mihaila, R., Legg, C., & Benade, L. (2016). Towards a philosophy of academic publishing. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(14), 1401–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1240987

- Peters, M. A., Oladele, O. M., Green, B., Samilo, A., Lv, H., Amina, L., Wang, Y., Chunxiao, M., Chunga, J. M., Rulin, X., Ianina, T., Hollings, S., Yousef, M. F., Jandrić, P., Sturm, S., Li, S., Xue, E., Jackson, L., & Tesar, M. (2020). Education in and for the belt and road initiative: The pedagogy of collective writing. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(10), 1040–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1718828

- Peters, M. A., Rizvi, F., McCulloch, G., Gibbs, P., Gorur, R., Hong, M., Hwang, Y., Zipin, L., Brennan, M., Robertson, S., Quay, J., Malbon, J., Taglietti, D., Barnett, R., Wang, C., McLaren, P., Apple, R., Papastephanou, M., Burbules, N., Jackson, L., Jalote, P., Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Fataar, A., Conroy, J., Misiaszek, G., Biesta, G., Jandri, P., Choo, J.S., Apple, M., Stone, L., Tierney, R., Tesar, M., Besley, T., & Misiaszek, L. (2020). Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19: An EPAT Collective Project. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655

- Ross-Hellauer, T. (2017). What is open peer review? F1000Research, 6, 588. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11369.2

- Ross-Hellauer, T., & Görögh, E. (2019). Guidelines for open peer review implementation. Research integrity and peer review, 4(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-019-0063-9

- Stewart, G. (2016). Reviewing and ethics in the online academy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(5), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.950804

- Stewart, G., Arndt, S., Besley, T., Devine, N., Forster, D. J., Gibbons, A., Grierson, E., Jackson, L., Jandrić, P., Locke, K., Peters, M. A., & Tesar, M. (2017). Antipodean theory for educational research. Open Review of Educational Research, 4(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2017.1337555

- Tesar, M. (2020). ‘Philosophy as a method’: Tracing the histories of intersections of ‘philosophy,’ ‘methodology,’ and ‘education’. Qualitative Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420934144

- Trafimow, D., & Rice, S. (2009). What if social scientists had reviewed great scientific works of the past? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01107.x

- ‘What is open peer review? A definitive study.’ (2020). Enago Academy. https://www.enago.com/academy/what-is-open-peer-review-a-definitive-study/

- Wyatt, J., Gale, K., Gannon, S., & Davies, B. (2011). Deleuze & collaborative writing: An immanent plane of composition. Peter Lang.