?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

There has been an excellent series of formative articles centring on Bernard Stiegler (1952-2020) as an inspiration to pedagogical thought; this is a summative article written from the perspective of after his death. Stiegler argued that education is ontologically crucial to human development, wherein technics or the ‘not-experienced-condition(s)-necessary-for-experience’ are crucial to humanity’s ability to create its own existence. Technics make possible the technologies underpinning contemporary Anthropocentric existence. While entropy poses the cosmological threat of death to life, technics supports negentropy or the collecting and marshalling of energy opposed to entropy. Education is a crucial means of social negentropy, however all human agency is characterized by the pharmakon of more entropy or increased negentropy. The tension is inevitable in the pharmakon between on the one side, care and cure; and on the other, poison and death. In this article, we ask: ‘Given his suicide, what sort of pharmakon was Stiegler for himself and for us?’1 The authorial “I,” ‘Bernard Stiegler’ is no longer a living critic of social entropy or of proletarization and ‘technoscience’; what do we now make of his oeuvre for education? We will point to his inversions and purposeful mis-interpretations of Heidegger and Derrida as crucial to his oeuvre. Stiegler’s phenomenal being has ended; what technics have been strengthened and specifically: ‘What now of education?’

Introduction

Bernard Stiegler’s (1952-2020) contribution to our understanding of pedagogy centres on two points: (i) education is crucial to the ontology of human social being; and (ii) the Anthropocene of proletarization, digitalization, and consumerism threatens education and thereby the very being of the human. To parse that sentence: (i) the ‘anthropocene’ is the historical period of an essentially manmade environment, (ii) which is a product of the industrial and information revolutions which were/are economically powerful but have stripped or proletaritized large portions of society of their autonomy, expertise and savoir faire; (iii) currently the coming of AI and advanced marketing techniques (digitalization & consumerism) threaten to reduce humanity’s savoir vivre to shreds. Stiegler questions the fundamental philosophical groundings to education and critiques the forces that threaten to destroy the very possibility of education and threaten life itself. Stiegler’s suicide in 2020 problematizes his message. Ever since Socrates’ ‘Apology’, the circumstance and self-vindication of the philosopher’s death has been considered a crucial touchstone of the philosopher’s thought. And for a writer who repeatedly asked if life is worth living in this society and culture, that he commited suicide is fundamentally relevant. As Jean-Luc Nancy (Citation2021) pointed out in his requiem to Stiegler, melancholy and despair were always in the background to Stiegler’s calls for action and political change. The conflict between hope and anguish, or belief in social-political action and fear for totally corrupted economic and political leadership, was a leitmotif to Stiegler’s work. If you wish this was his pharmakon, or a Janus faced commitment to social and economic justice, coupled to a matching fear of how organization and power operate.

In Bernard’s words, ‘a philosopher’s philosophy is meaningful only when it is exemplified by his way of life; that is, of dying (Mohan, Citation2021, p 100; authors’ translation).

Stiegler agitated theoretically and practically against economic exploitation, political inaction, and intellectual denial. He fought the entropy of what he saw as the social and intellectual loss of energy in the abandonment of the will-to-live and the betrayal of democratic engagement. He proposed an intellectual and political strategy of ‘negantropy’ or of energizing oneself and others to take engaged action. Having written a philosophy against entropy and in support of negentropy, did entropy or death actually win out? Stiegler, the writer who could publish a thousand pages per year remained mute about his chosen death.

It was typically Stiegler to pose a theme, such as technics, and then develop it as inspired by Heidegger, Derrida, and classical Greek thought; in order to return to contemporary events, such as digitalization and the development of the Internet, or financialization and the globalization of hyper-capitalism, or the growth of the political far right and of social violence. Education was never far out of sight, whether as despair in regards to school shootings or the lack of attention and concentration of students, or in defence of necessary passing of past accomplishments on to future generations. Stiegler liked to say ‘What I call ….’ and to make ‘calls-to-action’. He had a penchant for neologisms and to giving Greek names to things.

EPAT published a series of articles during Stiegler’s lifetime that powerfully introduced readers to Stiegler’s naming and neologisms, of his pedagogical activism (Bradley, Citation2015, Citation2021; Bradley & Kennedy, Citation2020; Featherstone, Citation2019, Citation2020; Fitzpatrick, Citation2020; Forrest, Citation2020; Irwin, Citation2020; Mui & Murphy, Citation2020; Ross, Citation2020). For readers who have not (yet) decided to read his writings or who seek a pathway to understand the significance to education of what they have started to read, these articles provide the needed pathway. It is now the moment to assess Stiegler’s oeuvre from the distance of his death. Thus our goal here is different from what is already ‘out there’. If there is to be any more ‘work-in-progress’ it must be our own and cannot be his.

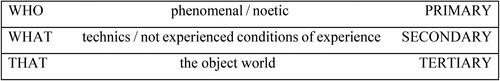

Summarizing, Stiegler claimed that education was currently experiencing a ‘post-truth’ crisis wherein the social processes of memory, exteriorization and dissemination were under attack. He claimed that “technics” - that is, the processes that underpin the very possibility of knowledge, were endangered. He explored (explained in Section 1) how: (i) primary or experiential and phenomenal, (ii) secondary i.e. the assumptions and grammars that underpin action and experience, and (iii) tertiary or coagulated and solidified objecthood; are distinct but depend the one upon the other.

Contemporary social, physical and historical entropy he claimed are not only destroying the climate but also the very possibility of knowledge and socius. The crisis of the Anthropocene is a crisis of physical and social technics that threatens education. Stiegler thus identifies the Anthropocene with entropy — the crisis in the physical and social environment entails a loss of activity and of life. The ‘Neganthropocene’ is the opposite or a social and environmental regime of increased energy and activity. Entropy leads to death; life requires ‘negenthropy’ or the absorption of more and more energy. Human social action produces ‘negenthropy’ via knowledge creation and dissemination, which enables social and economic growth, achievement and complexification. Neganthropy is a human physical and social necessity (Stiegler, Citation2017, Citation2020b; Stiegler & Collectif, Citation2020). The technics of negenthropy, or the skills, social arrangements and assumptions that make needed living action possible, are crucial to humanity’s very being. Shared processes of exteriorization, encapsuled in ‘science, truth and knowledge’ must not be destroyed, exhausted or depleted. But, knowledge can both be constructive and destructive, because it carries both care and chaos within it, as in the pharmakon of medicine and poison. Stiegler wrote insistently about the pharmakon wherein action and actant can all at once be negentropic or entropic, constructive or destructive, just or repressive, supportive or paralyzing (Stiegler, Citation2010a, Citation2012). It is logical to turn to Stiegler himself and to ask ‘What sort of pharmakon was he?’ Stiegler seems to have elevated the concept of the pharmakon to an ontological principle; ideas and actions inherently are cure and poison; that is, have positive and negative consequences. Thus, also his own defence of education. Have his descriptions of a crisis in the breakdown of the ability to pass on knowledge from the one generation to the other ultimately made us more aware of the importance of education or did they seed the culture of mistrust and panic? Did the underlying melancholy and possible despair of Stiegler, for instance implicit to his social and political critique but also in his suicide, reveal more about him than his explicit calls for action and justice?

Stiegler’s thought was grounded in what he retained and changed in Martin Heidegger’s philosophy (Stiegler, Citation1998, Citation2001, Citation2009, Citation2011a). From Heidegger in Being and Time came the famous distinction between the ready-to-hand and present-at-hand (Dreyfus, Citation1995; Dreyfus & Spinosa, Citation2003; Heidegger, 1996 [1927]). Carpenters work unthinkingly in the ready-to-hand, as they are not concerned with the existential conditions of thought, awareness and possibility that make their work on a construction site possible. And if their work is brought to a halt because of some breakage, failure or incompleteness of the tools or materials, the ‘objects’ about them become present-at-hand — that is, functionally displaced and no longer purposeful or meaningful. But again the ontology of activity is not revealed. Whether engaged in unreflective action or stopped in a world of ‘objects’ that lack (temporarily?) purposiveness; the ontological nature of existence is not revealed. Awareness of how consciousness opens itself to and frames existence, demands some other sort of existential awareness.

Heidegger’s goal is to investigate the ontology of world disclosure, centering on the unconcealedness that results in an ‘opening’ of awareness. Human being is ‘world disclosing’. But contemporary technology reduces subject and object to the status of ‘standing-reserve’. A Heideggerian example: the Rhine, as a source of electrical power, has been dammed up, converting it into a technological auxiliary of human manipulation’ (Heidegger, 1977 [1954]: 297). Nature is controlled, used and exploited. For Heidegger, ‘resource thinking’ frames the world as so much equipment alienated from human being or awareness. Technology hereby is a threat to human being (Ihde, Citation1979).

Stiegler rejects Heidegger’s dualism between ‘standing-reserve’ (the forest as timber) and openness to existence (hiking through the Black forest); i.e. of objects as allowed to present themselves to us versus objects as conceived of as for us. Stiegler does not divide the human condition into ‘self-belonging’ versus ‘worldly alienation’. Stiegler’s claim is that humanity is self-creating via its activities and not that humanity is self-destructive when its praxis limits the contemplative. Heidegger had disdain for welfare for all, prioritizing prerequisites for authentic existence; Stiegler embraces social justice as an existential and ethical goal.

Stiegler claims that the contemporary crisis of the Anthropocene has brought with it the ‘post-truth’ denial of awareness and responsibility. The energy, dedication and determination needed to face-up to difficult problems and deteriorating situations is now lacking. Instead of problem analysis and change plans, there is entropy or a comatose and passive regime of inaction. Repudiation of urgence threatens to overwhelm the neganthropic forces needed to observe, learn and react. Education, creating and passing on knowledge of the environment, is a necessary neganthropic force to the producing of the individuation of personal judgement, awareness, and consciousness required to make responsibilization, choice, and ethical awareness possible. Stiegler was committed to the creation of a contributory society of intra-active neganthropy, wherein self and Other freely co-constitute their social and economic relationships (Stiegler & Collectif, Citation2020). His model is one of cooperative deliberation and action, and not one focussed on Heideggerian individual consciousness and existential authenticity.

To develop and clarify these themes, Section One of this article will focus on Stiegler’s ontology and his interpretation of individuation by explaining the relationships between: (i) primary phenomenal consciousness, (ii) secondary underlying ‘technics’, and (iii) tertiary ‘technology’ and artefacts. Section Two examines différance, truth and knowledge in education and humanization; and in Section Three, we return to Stiegler’s Heidegger and the reinterpretation of dasein (or the thrownness of being) to examine how education stands central. We conclude examining the pharmakon of Stiegler’s persona and oeuvre, by providing our ‘take-aways’ and criticisms.

Technics and technology; the creation of humanity

Stiegler’s philosophical work centres on the triad of the Technics and Time books; the rest of his vast oeuvre is stronger on social phenomenology and politics. In the foundational philosophical work, Stiegler re-examined Heidegger’s themes of being and time (1994, 1996, 2001). Heidegger denied that quotidian activity or ontic perception reach consciousness of the ontological grounds of their ‘being’. Stiegler’s position is closer to Heidegger’s mentor Husserl; that is, noetic (in the mind) phenomenal awareness does not know the conditions of its own operations (the ‘technics’ of perception or of thought). But this is not, as in Heidegger, seen as an ontological theme. Phrased in terms of the aporia or presuppositions to consciousness: the preconditions of consciousness can never totally be in consciousness itself; i.e. consciousness is structurally enabled without fully knowing the foundations of its enablement. The physical world of physics, brains and synapses, exists in an altogether different realm to that of phenomenal awareness. Stiegler does not collapse any one of these levels into the others, or prioritize the one above the other, but assumes three levels of being ():

Figure 1. Stiegler’s three levels of being (based on Ian James, Citation2019).

In Stiegler, the three levels to awareness are described as: (i) primary retentions of basic sense data such as vision, hearing, smelling, touch; (ii) secondary retentions that are formed as memories, via the labelling, ideationing and textualizing of primary perception; and (iii) tertiary perception created when secondary perception is transformed into technology and ‘grammarized’ via writing, printing or audio-visual recording. The tertiary is exteriorized and trans-individual; while primary and secondary perception are mostly on the individual level. The co-constitutive relationship between the conscious subject or the who and the what of agency produces human being:

That which anticipates, desires, has agency, thinks and understands, I have called the who … its prosthesis, is its what. The who is nothing without the what … during the process of exteriorization that characterizes life … by which life proceeds by other means than life. The who is not the what. (Stiegler, Citation2009: 6-7, original italicisation)

If the individual is organic organized matter, then its relation to … a who, is mediated by the organized but inorganic matter of … the what … the what invents the who just as much as it is invented by it (Stiegler, Citation1998: 177-78, original italicisation).

Time is each time … characterized by … actual access to the already-there that constitute … its particular possibilities of “differantiation” and individuation … a reflection of the who in the what. The analysis of the technological possibilities … particular to each epoch will, consequently, be … of a who in a what (Stiegler, Citation1998: 236-37, original italicisation)

We need to unpack these quotes wherein the who is compared to the what and the that is a product of the what. The self or subject is the who; whilst the context and society – including the physical and cognitive equipment that constitutes them – characterize the what. Stiegler’s assertion is that the who is just as strongly a creation of the what as vice-versa. When humanity externalizes its being in the that of tools and language, humans cease to be exclusively biological and become co-defined by artefacts and words of exosomatization. Individual human life takes on the ability to receive and potentially give ‘equipment’ to others; even to others after one’s death.

The that or object world, forms the tertiary aggregation level. For instance, the brain is a that of synapses, chemistry and electromagnetic forces; but the ‘I’ has (next to) no phenomenal contact with any of these. Nor do they play much of a role in the technics that underpin human awareness or society. Stiegler’s emphasis is on the technics that make identity and social existence possible. Technics entail capabilities and agency that get realized in the form of technologies, which in education are passed on from the one person to another and from the one generation to the next. Stiegler explores how the ability to externalize the self in the physical and mental equipment of the that of technologies underpins human individual and social identity (Stiegler, Citation2020a, Citation2008a).

Humans make their existence in the that of time; time is the existential milieu of phenomenal existence. Time is crucial to the human technics, making perception, ideation, and identity possible. Experience of phenomenal consciousness depends upon technics (Colony, Citation2010; Stiegler, Citation1998, Citation2001, Citation2011a, Citation2009). Perceived changes in identity, epochs, and circumstances entail difference(s) in how the that influences the what. The paradigms and capabilities that underpin and make possible social and physical technologies — i.e. the that, are technics. Technologies are in effect the ‘memory-machines’ of technics (see, for example, Barnet, Citation2013). Technics constitute the technologies of experience, such as writing, printing, recording, et cetera. Without human technics, there would be no technologies; technologies are through and through human.

Clearly, Stiegler’s ontology of technics is very different from the Heideggerian conviction that modern technology endangers, if not destroys, human ‘being’ (Heidegger, Citation1966, 1977 [1954]; Rappin, Citation2015; Stiegler, Citation1998, Citation2001, 2011). Of course, Heidegger posited that we cannot and should not want to get rid of all technology; but he also stressed that technology’s redefining of nature as so many resources, and existence in terms of equipment, was an existential threat to human being. In Stiegler, technology resulting from technics is a product of human ontology; an ontology that can produce care or carelessness, thought or thoughtlessness, negentropy or entropy. The pharmakon or existential ambiguity of praxis is fundamental to Stiegler’s thought; human action can produce cures and be medicine, or it can be poison and destructive (Stiegler, Citation2010a).

Stiegler voiced his ontology through the myth of Prometheus as told by Protagoras in Plato’s dialogue (Stiegler, Citation1998). It is a myth of epiphylogenesisFootnote2 or of the becoming of the human/world relationship, wherein humanity is left naked and shivering with insufficient qualities to assure its survival. To ameliorate this, fire and the arts were stolen from the gods; whilst Zeus sent Hermes to give humanity the capacities for cooperation, organisation and government. Humanity, because it is ontologically incomplete and weak, has to depend on its technologies to exist. The physical human ‘being’ of the ‘naked ape’ is insufficient; but humanity equipped by the technics of its capabilities can prevail. Via the myth of Prometheus, Stiegler takes distance from Heidegger; the key philosophical problem is not humanity’s insufficient contact with its ‘being’, but the complex and unstable nature and insufficiencies of concrete situated ‘being’. For Stiegler, technics or mental and practical abilities and technologies, starting with fire, are necessary for human survival. We note that life or death, survival or extermination, entropy or negantropy, are throughout fundamental terms to Stiegler’s argument.

Stiegler asserts that human ontology allows humanity to not see and thus to ignore death (entropy) by striving for aliveness and creative action (negentropy). Mortality as a struggle to avoid inaction, paralysis, and stasis is crucial; but not as Heideggerian existential ‘being-towards-death’. Stiegler asserts that the human ability to ‘forget’ mortality but to know temporality, is crucial to human ontology. In awareness, ideation and knowledge, humans are ‘god-like’ — that is their ‘knowledge’ can be timeless and potentially ‘True’; while in individual being, humans are limited and finite.

Human ‘being’ or ‘existence’ is a complex phenomenal process, wherein perception can lead to knowledge, whereby humans make their own world. But, disastrously, humans have made the Anthropocene. Technics are inevitable, but whether the resulting technologies will be for the good or the bad, will be entropic or negentropic, is not predetermined. There is one cosmological certainty; that of entropy; whereby there is one necessity for life and existence, negentropy (Stiegler, Citation2018a). Stiegler’s goal was to organize life-enhancing negentropy; for instance, through knowledge and education.

Summarizing, Stiegler assumed that: (i) humanity individuates itself via technics wherein the human self or the who is produced via its what. (ii) Individuation provides possibilities of change in a that, but there are always risks of disaster and extinction. Humanity creates itself through its technics and preserves what it has created via ‘grammatization’ or inscriptions embedded in technologies of representation. Humanity’s capacity to learn is no add-on; it is the very crux to its anthropology. Stiegler follows SimondonFootnote3 in seeing technics as co-constituting ‘participative-contributative localities’ (Stiegler & Collectif, Citation2020; Crepon & Stiegler, Citation2007); but there is no certainty that these ‘localities’ can survive and flourish.

There is potential conflict here between technics and technology. Technics produce technologies that facilitate world-changing action. For instance, the printing press made the enlightenment possible. Likewise, the forming of the modern state depended upon the technologies of the railroad and telegraph to facilitate contact over greater distances and catalyse nation building. But these technologies also created monopoly practices, extreme speculation and exploitation, as well as anti-democratic and demagogic political processes. Stiegler stresses that industrialization destroyed much worker knowledge. The externalization of manual skills in machines facilitated increased productivity, but reduced work to mindless labour (Stiegler, Citation2020a, Citation2011b, Citation2010a). Stiegler claims that marketing is doing something comparable to contemporary existence. Knowledge of sociability and the situational ability to enjoy life supposedly is being extinguished by the tools of mass consumerism (Stiegler, Citation2013, Citation2008b). The social and physical technologies of crowd manipulation are destroying individual awareness and making for mental passivity. Stiegler calls these processes proletarization which is characterized by losses of awareness and agency (Stiegler, Citation2010b).

Humanity creates its own existence in the time-space of human activity, whereby time is the conceptual holder of human activity; i.e. time is a human creation (Stiegler, Citation1998). This is a settlement of accounts with Heidegger, who claimed that ‘time’ was a product of ‘being’. For Stiegler, tools and their uses do not constrain ‘being’. Humanity has created itself by making the world within which it exists. Technics support the generative processes wherein humans and their technologies are bound to one another (Stiegler, Citation2003, Citation2017; see also Abbinnett, Citation2018).

‘What of education?’

There has been a lot of university-bashing (Grey, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2018). Universities have been held responsible for ENRON-like corruption and neo-liberal economic ruthlessness (Ghoshal, Citation2003; Mitroff, Citation2004). Students supposedly have embraced greed and self-interest with utter disregard for human well-being (see Grey, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2018). But contrastingly Stiegler insists that the creative capabilities of technics, sustaining individuation, questioning, autonomy and truth, comes from the university:

… [the] organs of transmission and interiorization are universities, which themselves emerge from philosophy, and which constitute the history of truth – are currently undergoing massive change, if not complete disintegration and destruction. It is in this context that we can refer to ‘post-truth’. (Stiegler, Citation2020a, p 101)

Stiegler champions critical informed questioning and awareness, which he identifies with the struggle against proletariatization and the Anthropocene (Stiegler, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Education and universities have the task of organizing and protecting individuation and shared existence by opposing ‘post-Truth’ (Stiegler, Citation2020a). Much of Stiegler’s work has been about the political, intellectual and business elite’s inability and unwillingness to attempt awareness, analysis, or understanding by refusing to acknowledge the downside to the modern technologies of technoscience (Stiegler, Citation2008b, Citation2010b).

Technics make technologies that make us (Stiegler, Citation2020a). But technics entail risks; a radical ‘reflexivity’ is needed to see, critique, and exert control over the technologies co-individuating contemporary existence. For Stiegler, knowledge is not something inside individual heads, but a form of relatedness and collective work (Stiegler, Citation2008a, Citation2010a). The liberal vision of education as the maximum development of the individual’s abilities, wherein learning and knowing are individual matters, is for Siegler an ideological misrepresentation.

Stiegler’s conceptualization of the relationship between technics and technology frames his understanding of everyday being. Stiegler has reframed Heidegger’s dasein as agency. In Heidegger, dasein or ‘throwness’ refers to human existence as lost in the quotidian, unable either to know the foundations to its own ‘being’ or even that ‘being’ exists. As the world pre-exists our entry into it, the self always comes too late and after-the-fact, entering into an existence that already is. In Heidegger dasein points to a generalized condition of human powerlessness; but in Stiegler, humanity creates the conditions of its own existence.

Learning entails transference, critical awareness and creative action. Learning is a product of relatedness and of common endeavour; wherein education functions as an organized social source of individuation. In education the brains of learners are physically changed, when socialized to read, write, critique, synthesize and analyse. The human brain is not born to do all of these things; it is re-formed physically and in its awareness by education. The internalization of social memory via language raises the person “above themselves and above their biological and nervous automatisms …. interiorizing both: (i) symbolic, technical and hypomnesic categories …; and (ii) the social relations that grant access to these categories through social rules … constituting savoir-vivre and attentional forms of all kinds” (Stiegler, Citation2020a, p. 200).

But the externalized can turn back on primary and secondary perception, having a strong ability to influence experiencing:

Man is a technical being, that is, unfinished. To survive, he must produce artificial organs, learn to practise these artificial organs, and, for this, institute social organizations that articulate the relations between generations, and between producers and practitioners of existing and future exosomatic organs. … To make it possible to learn how to practise the artificial organs … is the role of education … and by adding the new exosomatic organs always required by … (1) the psychic individual; (2) the … technical system; [and the] (3) social organizations; this exosomatic being must find its way towards what remains always yet to come … Truth is the criterion of such a search. (Stiegler, Citation2020a, pp. 292-293)

Technics is the what individuating the who, with currently a that of (hyper-)capitalism and the anthropocene in the background. But a technics of social paranoia, violent acting-out and Nietzschean resentiment, can do untold harm. The who is born as ‘yet-to-be-educated’ into a pre-individual milieu where the what of negentropic technics can support the that of action grounded in truth-finding. The more the norm is to act unreflectively from commonplace assumptions, the further the distance is to awareness or to the ‘What is?’ that supports negentropy.

That or externalized not-phenomenal knowledge is crucial to human existence. The that of social-economic relations which are humanmade, but not (sufficiently) human understood, is crucial to our present social existence. Likewise, the that of computers, information technology and AI are outside of most of our understanding but crucial to our existence. Stiegler makes use of Jacques Derrida’s theory of ‘grammatization’ to explain the move from primary experience to memory, and on to the externalized that of ‘writing’ (Derrida, Citation2002). ‘Writing’ here takes in all codified, cogulated and condensed forms of that. It is the that which facilitates accessibility and potentially makes ideation shareable. However, ‘grammatization’ changes what it encounters, moulding it into the collectively expressible and acceptable. The transindividuation, that the technologies of communication make possible, come at a price. Humanity’s exosomatic organs or technologies of textualized thought have made modern science and industrial economy possible. But they have also produced military violence and scapegoating, as well as propaganda and social injustice. The pharmakon of technics is fed by the who and its phenomenal experiencing, as projected forward into the that of the technologies of economic and social existence. Education grants “access to reflective thought, that is, thought that is not automatic but deliberate, and socially elaborated in dialogical relation with others … that make possible the encounter with these others. (Stiegler, Citation2020a, p 201) Education is crucial to human development, but its capabilities remain ambivalent; both ‘authenticity’ and ‘Nazification’ are educational possibilities. Successful technologies are pharmakons: the automobile as a means of mobility produced congestion; the world-wide-web as free access to information has produced informational and economic behemoths like Facebook.

Education is a regulatory mechanism of the tertiary wherein the capabilities to produce, evaluate and change the that are taught. The technics supporting individuation pass via education from the one generation to the next. For society to maintain itself, shared technics must underpin the development and implementation of its physical and social technologies. Learning in institutions of education, co-produces the ‘we’ making it is possible for people to live productively and peacefully together. But if the common beliefs and shared identities underpinning the tertiary collapse, the resulting cacophony brings on a crisis of social disintegration.

Individuation is complex, requiring the acceptance of a shared technics, but also needing différance, which again is a concept of Derrida’s. In différance, there is relatedness and interaction, similarity and linkage; but also, divergence and variance. Tertiary transmission requires that ideation and activity are captured, recorded, and passed along in the that. This is a complex process as the secondary retentions that form the basis of the tertiary, must be individuated in the what of the individuated self. In différance, there is an acceptance of the necessary multiplicity, divergence and complexity of the interaction of the three levels. Every ‘reading’ is just a bit different from every other one. Communication, interpretation and understanding, require a willingness to know and respect that persons, situations and ideas, differ.

But just as Stiegler reversed some of Heidegger’s basic positions, for instance by embracing technics as humanization rather than seeing technology as sources of alienation, he does the same with Derrida’s thought. Stiegler stresses entropy versus negentropy, cure versus poison, technics versus technology; while Derrida understands relatedness as polyphonous, contextual and intra-active. Stiegler converts Derrida’s différance from an ongoing circumstantial process into a series of either/or’s. For Stiegler, the one idea, concept, position or assertion, is not the other one; the ‘Truth’ of différance is in Stiegler that of an Aristotelian ‘a non-a’. According to Stiegler, différance is a vigorous engaged activity; in ‘post-truth’ the structures that constitute and defend ‘a

non-a’ are made inoperative, whereby individuation supported by the technics of ‘truth-finding’ fails. According to Stiegler, ‘social media’ have locked their publics into closed loops of repetition, wherein the determination of ‘Truth’ is replaced by confirmatory noise (Stiegler, Citation2020a, Citation2008b, Citation2011b). The pursuit of ‘Truth’ demands that the query ‘What is?’ is rigorously applied. Différance in support of ‘Truth’ requires the understanding, interpreting, observing and serious examining, of the ‘texts’ of technics’. The ideas, insights, concepts, procedures, models, categorizations, et cetera, needed to make the needed assessments, come from the pre-individual milieu that facilitates individuation. Différance leads to comparisons, judgements and deliberation. Minds that reject différance do not individuate and fall into endless repetition. Individuation requires possibilities, choices and alternatives; but it must accept that ‘a and not-a’ are two different things, for post-truth relativism to be avoided. Humanity’s that depends upon différance and boundaries between ‘a’ and ‘not-a’. To create and preserve the physical and social technologies that underpin the that, the différance between ‘a and not-a’ has to be supported by the prevailing technics.

Stiegler’s ontology posits that human existence depends on its uses of technology; without the successful uses of technology, humanity is naked, weak and hopeless. Refusing to acknowledge différance endangers the necessary technics that produce the feeling that life is worth living (Stiegler, Citation2020a, p 119 & 106). In a paper delivered during the last six months of his life, Stiegler explored what he saw as the contemporary technics, which “comes to poison the life of humans making them anxious,” and is not life confirming (Stiegler, Citation2020c). Mortality has to be sufficiently denied for negentropy to prevail. But contemporary individuation “traumatizes our youth, to the point that they can at times become suicidal” (ibid.). The technologies of Anthropocene excess, have loosened the “boundaries - the sense of limits, madly exposing [humanity] to stress” (ibid.). In the pharmakon of contemporary existence every opportunity is a danger, every solution is a possible trap, every victory could become a defeat. The exosomatic processes of knowledge are insufficiently leading to humanization; they have become sources of trauma. Throughout his oeuvre, Stiegler championed negentropic action and never seemed to doubt the potential humanizing role of technics; but in this late article the tone is different. The dark-side to Stiegler’s ontology is that individuation via technics can produce extreme suffering. A “stage of techno-logical shock that dis-adjusts the social and symbolic systems can be archi-traumatic” as humanity becomes “the bearer[s] of overwhelmingly negative protentions” (Stiegler, Citation2020c). The “stage of readjustment, that is of care,” wherein a new epoch, sensibility, psyche and morality emerges, may come too late (Stiegler, Citation2020c, our emphasis). Individuation is locked into the first stage when the “libidinal economy (that is, psychic individuation), political economy (that is, collective individuation), and exosomatization (that is, technical individuation),” are delinked (ibid. p. 10). The danger of ‘deindividuation’ and social entropy looms large.

Education must provide the care underpinning memory and supporting ‘grammatization’ (Stiegler, Citation2010a). Human technics via education engender the human capabilities needed to transcend mortality and impermanence. Technologies have to be instructed and preserved. Educational negentropy underpins humanity’s very existence. In the next section, we will examine the threat to education of the Anthropocene and the need for negentropy to counter the threat.

Education Revisited: Truth, Knowledge and the Hammer

The goal of the hammer metaphor in Heidegger’s Being and Time was to reveal a dilemma between activity, whose consciousness of its own foundations is non-existent; and an object-world, which is not lost in activity but wherein meaning and context are absent. Heidegger demonstrates that objects are never simply given; neither in activity, nor in isolated attention. The opening or clearing of consciousness whereby existential meaning is possible is constituted by human enframing. A set of existential conditions of possibility make revealing awareness possible. Awareness is to be brought forth by facilitating an authentic mode of revealing. While Stiegler writes about shared social circumstances of awareness and what facilitates just action; Heidegger focusses on needed processes of ordering for the revealing of true being and existence. Stiegler is a social thinker of shared existence and reality; Heidegger focuses on the enframing needed to achieve individual authentic being.

Tools are as important a theme for Stiegler as for Heidegger; but Stiegler reverses the logic. For Heidegger, tools and technology threaten to reduce awareness to the mindlessness of the ready-to-hand. Whereby technology blocks access to being, as awareness is distracted and perverted by gadgets, efficiency and consumerism. Stiegler acknowledges that all too often technology produces results unworthy of humanity, with processes that are socially and environmentally destructive (Stiegler, Citation2015, Citation2017, Citation2020b). But in a reversal of Heidegger, it is technics here that makes us human. Technics producing technology are humanity’s route to agency, truth and knowledge. Heidegger’s prioritization of ‘being’ as ‘enframing’ leading to ‘engagement’ existentializes his thought, with existence conceived of as dwelling or being-in the world. The mode of engagement is not one of intra-active or social ‘care’. Stiegler believes that Heidegger’s approach to ‘being’ is part and parcel of what led to Heidegger’s Nazi sympathies (Inwood, 2014; Stiegler, Citation2020a; Wolin, Citation1993). Heidegger’s disregard for quotidian existence and contempt for ‘das man’ is central to a disdain for the everydayness of praxis and dasein. Stiegler’s ontology is that of the ‘everyman’ trying to get-on-with-life. When faced by differing courses of action, Stiegler demands which is life-giving and preserving. Human tools or the hammers of the world are technologies that keep us alive. And education is a particularly crucial (meta-)tool, providing access to technics.

Stiegler identified Technics and Time 1, 2 and 3 (Stiegler, Citation1998, Citation2001, Citation2009, Citation2011a, Citation2018b) as “my analysis of Heideggerian ontology,” where the ‘Truth’ of human being is defined as the pharmakon of praxis. Summarizing: technics provides the resources necessary for individuation, catalysing, stabilizing and passing on prerequisite social and physical technologies. Technologies exosomatize human technics as knowledge available through ‘grammatization’. For technics to prevail and not be destroyed by the post-truth society, individuation must lead to a who, capable and willing to ask the ‘What is?’ question. Stiegler ultimately proposes a turn to cosmology, where knowledge:

…. has to again become cosmological, having to conceive orders of magnitude from microcosmic and macrocosmic points of view, that is, in terms of those localities found in the biosphere (life, noesis), in an expanding universe processually ordered by the thermodynamic arrow of time …. (Stiegler, Citation2020a, p. 298).

Entropy and negentropy for Stiegler form the absolute background to existence and knowledge. Without negentropy there can be no life at all; if entropy prevails all lifeforms die. Cosmology is described here in terms of thermodynamics and entropy. Ultimately, one cannot stop entropy, but one can temporarily divert it by confirming différance and by engaging in intra-relatedness and relational being. Différance entails attention and reflection, awareness and ideation (Derrida, Citation2002). Death or entropy is deferable via exosomatization, whereby humanity can achieve collective aliveness. Achievements and insights do not have to die with the person; via education human accomplishments can accumulate. Books, ideas, and technologies are objectified labour that by being questioned, understood and reflected upon, can remain ‘living’ (Stiegler, Citation2010b, Citation2011b, Citation2013, Citation2015). However, human social and physical technologies can lead to a proletarization of mindless passivity and social-economic enslavement. Individuation needs a technics rich in living possibilities. However, individuation is menaced by the Anthropocene and the contemporary threat to destroy the environment and the very possibilities of life. What humanity has produced is acting to destroy that very humanity, with technologies portending to be physically and mentally life-destroying; with “techno-logical performativity … based on the return effect of exosomatization on its own operation … [where as] the techno-logical performativity of physico-industry-cum-psycho-industry-and-neuroindustry, they outstrip and overtake the categories and procedures of academic verification and certification …. [in] a regime of non-truth … that rejects the criteriology of truth.” (Stiegler, Citation2020a, pp. 287-88)

Education demanding ‘What is?’ and ‘What is it worth?’ and ‘What is to be done?’ and ‘Why me?’; is being threatened by consumerist performativity. Instead of individuation, there is proletariatization; instead of growth in possibilities there is a closing down of capabilities and initiatives. Instead of desire there are only drives. The Anthropocene entails a loss of possibility with technology turned against existence. Denial in ‘post-truth’ cowardice and complicity produces increased anxiety. Work is needed; “the catastrophic situation that has been imposed on the biosphere as a whole …. Is now turning into the generalization of artificial intelligence – of which libertarian ideology tries to impose a transhumanist interpretation.” (ibid., p 282) For Stiegler, the neo-liberal ideology of TINAFootnote4 and of ‘technopopulism’ destroy what education is, must be, and what is needed for individuation and freedom to energize human existence. As education is an ontological necessity, its precarious current state is a sign of threatening entropy:

Post-truth is the ordeal of … digital tertiary retention [that] can, as calculation, overwhelm any neganthropic opportunity to bifurcate, that is, any possibility of exercising the faculties of knowing, desiring and judging … Does this mean that every possible will and every responsibility – if not all truth – are collapsing forever? Or does it mean that will and responsibility are still required, but in a wholly other way…? (Stiegler, Citation2020a, p. 296)

The answers to the rhetorical questions are not so easy; what would the ‘wholly other way’ look like? Stiegler tried to out-run and out-perform entropy, but did he succeed? Did his philosophy save life and/or destroy him? His human ontology frames existence as a struggle between entropy and negentropy, wherein human technics facilitates necessary technologies; but individuation of the self is not guaranteed and may well be precarious. Education is charged with holding the tripart structure of who, what and that together.

Much of Stiegler’s writing was about the contemporary disintegration of the necessary intra-action and/or relatedness of technics and technology. The mythic human ontology where humanity is born weak, naked and having to desperately make do with technology, was (and Jean-Luc Nancy (Citation2021) in his eulogy points in this direction) Stiegler himself. No human can be ‘equal to himself’ — the who is never complete or equal to itself. The oeuvre exists; the ‘self’ (Nancy quoting Stiegler) is ‘funest’. The ‘being-for-aliveness’ which Stiegler renamed negentropy and gave to education as its task, may really on the individual level, be an impossibility.

Conclusion

However strong the underlying melancholy is to Stiegler’s ‘being’; his oeuvre is rich in contributions to the defence of education (Stiegler & Collectif, Citation2020). Technics, as the point of departure, addresses the ontology of individuation as the fundament of education and not meritocracy wherein all learners develop to the maximum of their ability. Technics is living-knowledge, depending on différance begetting ever other technologies and possibilities. Entropy, leading to closure, is literally the death of learning. Individuation and thus life itself is endangered by consumerism, proletariatization, conformity and angst. Living pedagogical action, like all action, is a pharmakon, benefitting some outcomes, cutting off others, and making some things invisible. Tools and technologies that worked in the past may not do so now. Technics and thus humanity does not exist in a stable world of fixed truths. ‘Truth’ must always ask: ‘What is?’ respecting principles of ‘a and not-a’. Différance really exists; desires are not drives, negentropy is not entropy, cooperation is not narcissism. Thus, education plays a crucial role in creating and supporting the technics of mutuality and care. Technics are our lifeline; technophobia is a form of destructive self-hate.

Our positioning of Stiegler, like the EPAT articles we referred to in the beginning, is balanced between despair and hope. Philosophically we have stressed his purposeful revisions or (mis-)interpretations of Heidegger and Derrida wherein he played with his sources. Stiegler, we believe, rejected the prevailing appeal to liberal individualism, defending contributatory social ‘Truth-finding’ to be embedded within institutions of knowledge. But his (by himself) unexplained death problematizes his claims. Can shared human being really prevail or does entropy ultimately always win out? By identifying education with life itself, pedagogy gains an extraordinary importance not often attributed to it. If technics are existentially fundamental, but only sustainable by being passed on from generation to generation, then pedagogy and education are a motor to the continuation of human society. But we question: ‘Did Stiegler succeed or not in passing on principles of humanization via the technics of his actions?’ Will we, his successors, pursue the assertion of the ontological function of pedagogy? Stiegler’s philosophy is a tool (even a hammer) in pursuit of a living negentropic technics, wherein education is crucial to the effort to survive the Anthropocene. For us the dilemma, will Stiegler’s death ultimately lead more to nothingness than to continued collective cognitive and bodily individuation? In this article, we have worked to make the Stiegler-ian challenge clear; but the answers still await (our and your) further actions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hugo Letiche

Hugo Letiche is Adjunct Professor at Institut Mines: Telecom Business School Evry/Paris (FR) and Professorial researcher at Nyenrode Business University (NL). He is emeritus Professor from the Universiteit voor Humanistiek, Utrecht where he was director of the professional PhD program. His current research focuses on the ethnography of accountability and the translation of contemporary post-phenomenological philosophy to practice. His work is inspired by French critical philosophical and social thought. Recent books include: The Magic of Organization (2020) and L’art du sens (2019). He has published in AAAJ, Culture & Organization, JOCM, Journal of Curriculum & Pedagogy, Organization, Organization Studies, TATE: Teacher and Teaching Education, et cetera.

Geoff Lightfoot

Geoff Lightfoot is emeritus Reader at the Universiteit voor Humanistiek where he co-tutored the PhD professional program. He taught at Leicester and Keele Universities. He has published in Critical Perspectives on Accounting, ephemera, the Journal of Urban Affairs, Management and Organizational History, Organization, Prometheus, SSRN

Simon Lilley

Simon Lilley is Professorial Director of Research at Lincoln University UK where he is Professor of Organization & Management. He was Professor and Head of Department at Leicester University and has taught at Keele University. He has published in Academy of Management Learning and Education, Culture & Organization, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, ephemera, Organization, et cetera.

Notes

1 His suicide is ‘public knowledge’ as his death was so announced in the local newspaper.

2 A Steigler neologism meaning ‘a new relation between the human organism and its environment, wherein technics and the human are constitutive of each other’.

3 Gilbert Simondon (1924-1989) is the father of contemporary French thought about technics, technology and individuation; see Du mode d’existence des objets techniques (On the mode of existence of technical objects) (1958) Paris: Aubier.

4 TINA: ‘there is no alternative’ a slogan of neo-liberalism associated with Margret Thatcher.

References

- Abbinnett, R. (2018). The thought of Bernard Stiegler. Routledge.

- Barnet, B. (2013). with a foreword by S. Moulthrop, Memory machines: The evolution of hypertext., Anthem Press.

- Bradley, J. (2015). Stiegler contra Robinson. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(10), 1023–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1035221

- Bradley, J. (2021). Bernard Stiegler, philosopher of reorientation. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 53(4), 323–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1810379

- Bradley, J., & Kennedy, D. (2020). On the organology of utopia: Stiegler’s contribution. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(4), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1594779

- Colony, T. (2010). A matter of time: Stiegler on Heidegger. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 41(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071773.2010.11006706

- Crepon, M., & Stiegler, B. (2007). De la démocratie participative. Mille et une Nuits.

- Derrida, J. (2002). Of Grammatology. John Hopkins University Press.

- Dreyfus, H. L. (1995). Being-in-the-world. MIT Press.

- Dreyfus, H. L., & Spinosa, C. (2003). ‘Further reflections on Heidegger, technology, and the everyday’. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 23(5), 339–349.

- Featherstone, M. (2019). Against the humiliation of thought. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 51(3), 297–309.

- Featherstone, M. (2020). Stiegler’s ecological thought. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(4), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1665025

- Fitzpatrick, N. (2020). Questions concerning attention and Stiegler’s therapeutics. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 52(4), 337–347.

- Forrest, K. (2020). The problem of now: Bernard Stiegler and the student consumer. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 52(4), 348–360.

- Ghoshal, S. (2003). B schools share the blame for Enron. Business Ethics: The Magazine of Corporate Responsibility, 17(3), 4–4. https://doi.org/10.5840/bemag200317321

- Grey, C. (2016). A very short, fairly interesting book about studying organizations. Sage.

- Heidegger, M. (1966). Conversations on a country path in M Heidegger discourse on thinking. Harper & Row.

- Heidegger, M. (1977 [1954]). The question concerning technology. Harper & Row.

- Heidegger, M. (1996 [1927]). Being and time. SCM Press.

- Ihde, D. (1979). Technics and praxis. Reidel.

- Irwin, R. (2020). Heidegger & Stiegler on failure and technology. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1654855

- James, I. (2019). The technique of thought Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mitroff, I. (2004). An open letter to the deans and faculties of American business schools. Journal of Business Ethics, 54(2), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-9462-y

- Mohan, S. (2021). Une Bonne Nuit. In J.-L. Nancy (Ed.), Amitiés de Bernard Stiegler (pp. 97–106). Éditions Galilée.

- Mui, C. L., & Murphy, J. S. (2020). The university of the future: Stiegler after Derrida. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(4), 455–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1605900

- Nancy, J.-L. (ed). (2021). Amitiés de Bernard Stiegler. Éditions Galilée.

- Parker, M. (2018). Shut down the business school. Pluto.

- Rappin, B. (2015). Heidegger et la question du Management. Cybernétique, information et organisation à l’époque de la planétarisation. Éditions Ovadia.

- Ross, D. (2020). From ‘Dare to think’ to ‘How dare you!’and back again. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(4), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1678465

- Stiegler, B. (1998). Technics & time 1: The fault of epimetheus. Stanford University Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2001). La technique et le temps Tome 3, Le temps du cinéma. Galilée.

- Stiegler, B. (2003). Technics of decision an interview. Angelaki, 8(2), 151–168.

- Stiegler, B. (2008a). Prendre soin de la jeunesse et des générations. Flammarion.

- Stiegler, B. (2008b). Économie de l’hypermatériel et psychopouvoir. Mille et une Nuits.

- Stiegler, B. (2009). Technics & Time 2: Disorientation. Stanford University Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2010a). Ce qui fait que la vie vaut la peine d’être vécue Paris: Flammarion. (What makes life worth living: On pharmacology. Polity.

- Stiegler, B. (2010b). For a critique of political economy. Polity.

- Stiegler, B. (2011a). Technics & Time 3: Cinematic Time and the Question of Malaise. Stanford University Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2011b). The decadence of industrial democracies. Polity.

- Stiegler, B. (2012). Relational ecology and the digital pharmakon. Culture Machine, 13, 1–19.

- Stiegler, B. (2013). Pharmacologie du front national. Flammarion.

- Stiegler, B. (2015). La société automatique-1 L’Avenir du travail. Fayard.

- Stiegler, B. (2017). Escaping the Anthropocene. In M. Magatti (Ed.), The crisis conundrum (pp. 149–163). Springer International Publishing.

- Stiegler, B. (2018a). The neganthropocene. D. Ross (ed.) (tr.). Open Humanities Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2018b). The order of truth. Paper presented at Nijmegen Radbout University.

- Stiegler, B. (2020a). Nanjing lectures 2016-2019. Open Humanities Press.

- Stiegler, B. (2020b). Qu’appelle-t-on penser? La leçon de Greta Thunberg Tome 2. Les Liens Qui Liberent.

- Stiegler, B. (2020c). “The Initial Trauma of Exomatization” Paper delivered SOPSI Rome 19 February.

- Steigler, B., & Collectif International (2020). Bifurquer: L’absolue nécessité. Les Liens qui Libèrent.

- Wolin, R. (ed.) (1993). The Heidegger controversy: A critical reader. MIT.