ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a global crisis in higher education, affecting all aspects of university work and practices. This article focuses on student experiences, in particular by problematising academic and wellbeing support available to non-traditional students. This article proposes an original approach to student support as comprising social networks that are dynamic, reciprocal and involving a variety of formal/informal actors. We draw on interviews with 10 non-traditional students from a UK university to explore the nature of their student support. Our findings suggest that support networks for non-traditional students tend to exclude formal support services and centre primarily around family (wellbeing support) and fellow students (academic/wellbeing support). While these findings problematise the lack of institutional support in student networks which is likely to further disadvantage these students, it questions the dominant deficit views of non-traditional students. In particular, the interviews highlight the resourcefulness of close interactions and emphasise the importance of approaching student support as a dynamic network of informal and formal actors when responding to crisis situations such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a global crisis in higher education (HE). To ensure the ongoing delivery of HE during the pandemic, universities rapidly introduced new practices, including shifts to online learning and teaching and innovative digital communication tools (see Clow, Citation2020; Clune, Citation2020; Lederman, Citation2020). While such reforms have been welcomed as a means to keep universities “open”, emerging scholarship from a variety of global settings has drawn attention to significant challenges these reforms present. This includes, for instance, the quality of teaching practices that resulted (García-Peñalvo et al., Citation2020; Mishra et al., Citation2020; Wahab, Citation2020), as well as the effects of the pandemic on academics and their workload (Tarman, Citation2020; Watermeyer et al., Citation2021). Within this paper we argue that there is a pressing need to explore students’ experiences of Covid-19. To date there has been limited scholarship in this area. Predominantly, this research highlights the effects of the pandemic – and particularly the closure of physical campuses – on students’ mental health (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020; Son et al., Citation2020), their access to resources (Aguilera-Hermina, Citation2020; Son et al., Citation2020) and engagement with online modes of teaching (Eringfeld, Citation2020; Nambiar, Citation2020). This paper aims to augment this emerging scholarship, therefore, by spotlighting support for non-traditional students in the UK. Both Universities UK (Citation2020)Footnote1 and the Sutton Trust (see Montacute, Citation2020) have raised concerns about the Covid-19 implications on widening participation in UK HE. Universities UK (Citation2020) also argued that “cold spots” will increase in terms of lack of support available to disadvantaged students, while demanding that the Government takes actions “particularly for those students from disadvantaged backgrounds, who will suffer from prolonged absence from more traditional support” (p. 4). As state response to student support needs during Covid-19 has been largely absent, it makes this project even more timely.

This qualitative study included 10 interviews with non-traditional students from an elite collegiate university in England. We apply the term non-traditional student to capture diverse student experiences related to (for example) being a first-generation student, a student from a lower socio-economic background or a mature student. Furthermore, we recognise that such students can be both “home” and “international” in origin as is also evident from our sample. We borrow Christie’s (Citation2007, p. 2446) broad definition of non-traditional students as those “who would not, in previous generations, have been expected to attend university”. Our inquiry centres around the following questions: What were the key issues students encountered during the Covid-19 crisis? What support networks did students develop to address these issues? We propose an original approach to student support as comprising social networks that are dynamic, reciprocal and involving a variety of formal/informal actors. Like Wellman (Citation2001, p. 228) we argue that (student) communities function in networks, and that these networks of interpersonal ties “provide sociability, support, information, a sense of belonging and social identity”. When attempting to facilitate student support for academic (learning/coursework) and wellbeing (mental health) purposes, it is therefore essential to consider what support networks students develop to reconcile the temporary loss of the university campus (Raaper & Brown, Citation2020).

In this article, we argue that the Covid-19 pandemic is “a mirror of sorts, a means of common reflexivity” (Marginson, Citation2020, p. 1395), enabling us to gain an understanding of the support experienced by students from non-traditional backgrounds. Its overall aims are to increase the sector-wide understanding of how to support non-traditional students in times of crisis and to offer an original conceptual lens through which to explore and develop student support as social networks.

Non-traditional student experiences of higher education

It is widely known that HE is socially stratified with those from more affluent backgrounds generally accessing and succeeding in universities at a larger scale than those from disadvantaged sectors of society (Bathmaker et al., Citation2016; O’Shea, Citation2016; Reay, Citation2018a). Recent UK statistics for 2018/19 show that students from affluent UK areas are twice as likely to progress to HE as those from the most disadvantaged areas; similarly, private school students are nearly three times more likely to attend high tariff universities than state school graduates (UK Government, Citation2020). In addition to statistical inequalities, the pre-Covid-19 widening participation research has highlighted a number of concerns related to non-traditional student experiences. We acknowledge that there is some evidence to suggest that non-traditional students have a higher resilience for handling university demands and adversities (Chung et al., Citation2017) and a strong motivation to succeed in their academic studies (McKavanagh & Purnell, Citation2007; McKay & Devlin, Citation2016). However, most widening participation research reveals the complex and disadvantageous experiences of non-traditional students which deserve further attention. Research on first-generation students in particular (e.g., see Meuleman et al., Citation2015; O’Shea, Citation2014, Citation2015; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019) has argued that students who are among the first in their family to enter university struggle with confidence and lack of support from role models who may ease their transition to HE. There is also a significant attrition rate among these students, who may feel different, lonely or isolated (O’Shea, Citation2016). Common explanations of these experiences centre on both the students’ shortage of social and cultural capital that could help navigate their transition to university (Meuleman et al., Citation2015). Hope and Quinlan (Citation2020) also argue that mature students face similar challenges when engaging with academic communities. Furthermore, mature female students often have caring responsibilities, adding a further layer of complexity to managing study, work and family life (O’Shea, Citation2014).

While differences exist across non-traditional student groups, most of these troubling experiences can be attributed to students’ socio-economic background and related financial struggles. Many are expected to engage in part-time employment to subsidise the high costs associated with university study (Antonucci, Citation2016; Hordosy & Clark, Citation2018; Hordosy et al., Citation2018), making participation in university life even more difficult. Research on working-class students, in particular, has highlighted that these students (and often due to their lower economic and cultural capital) tend to be less integrated in university life than their middle-class counterparts (see Bathmaker et al., Citation2016; Reay, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Reay et al., Citation2010; Rubin & Wright, Citation2017). What is more, they tend to become “marginalised outsiders within” (Reay, Citation2018b), which is particularly the case for students in elite HE settings. Research undertaken in the UK (see Coulson et al., Citation2018; Crozier et al., Citation2008; Reay, Citation2018b) has shown that working-class students struggle to fit in with the social life of the university, often disassociating themselves from support and social groups on campus. Similar findings are echoed by Rubin and Wright (Citation2017) who argue that working-class students in Australia are less engaged in campus life due to financial constraints and experiences of not fitting in.

Pre-pandemic research therefore indicates that non-traditional students were already less likely to feel at “home” on campus and interact with traditional forms of university life and support. It is important to note here that, while most widening participation research focuses on home students, there are often apparent commonalities and crossovers between home and international non-traditional groups (Taylor & Scurry, Citation2011). Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, those who are mature, or those who are first generation, experience similar financial and social challenges when integrating to university life, which are independent of their international/home student status (Taylor & Scurry, Citation2011). It is expected, however, that ethnic, linguistic and cultural differences around notions of “belonging” and “fitting in” can add a further layer of complexity to international students’ transition to HE (Cena et al., Citation2021; Hale et al., Citation2020). Informed by the extensive widening participation research, we argue that it is particularly important to explore student support in the Covid-19 context since the closure of physical campuses has required students to engage with online studies from their “home” environments, thus disrupting the traditional campus experience. While there is currently little if any research on non-traditional student experiences of Covid-19 in the UK, the wider scholarship has indicated a number of relevant issues.

Understanding student challenges during Covid-19

As discussed above, widening participation research undertaken before the pandemic has highlighted many financial and social challenges for non-traditional students. We now move on to contextualise these issues within the Covid-19 setting, drawing on the emerging research in the area. Student challenges during Covid-19 can be broadly grouped into those of an educational, emotional and environmental nature (Aguilera-Hermina, Citation2020). For the first of these, it is known that students have preferred face-to-face teaching over online education (Eringfeld, Citation2020; Nambiar, Citation2020). It is also evident that students have experienced various negative emotions, particularly boredom, anxiety, anger and hopelessness (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020). For instance, findings from a survey undertaken by Son et al. (Citation2020) (sample of 195 students in a large public US university) suggest that 71% of the respondents reported increased stress and anxiety, with stressors including: worry about their own health and of their loved ones; difficulty of concentrating; disruptions to sleeping patterns; decreased social interactions; and increased concerns about academic performance. The emotional effects of the pandemic are important as students constitute a vulnerable group for mental health issues in the light of their transitions to adulthood and the common financial difficulties of this population (Husky et al., Citation2020; Son et al., Citation2020).

It is the environmental challenges during the pandemic, however, that deserve particular attention for the non-traditional student population. These include both the issues around suitable study environment and financial security. In terms of the first, Aguilera-Hermina (Citation2020) argues, based on a survey of 270 students from one university in the US that their biggest challenge was being able to concentrate on studies while living at home. Family members, noise and housework caused significant distractions, and the more people who lived in the household, the less able were students to focus on studying (Aguilera-Hermina, Citation2020). Similar findings were echoed by Aristovnik et al. (Citation2020) who surveyed over 30,000 students across 62 countries and found that almost half of the survey respondents did not have a quiet place to work. As such, environmental challenges are a particular issue for non-traditional students with limited household space. Additionally, a large-scale Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) consortium surveyFootnote2 in the US found that first-generation students, working-class students, and students with caring responsibilities were less likely to have safe and suitable learning environments. Moreover, they also experienced heightened financial hardships (Chirikov et al., Citation2020; Soria et al., Citation2020). Soria and Horgos (Citation2020) argue that the pandemic has disproportionately affected students’ financial hardships based upon students’ social class background. This is unsurprising, given that many non-traditional students tend to work part-time to subsidise their studies (see Antonucci, Citation2016; Hordosy et al., Citation2018) and may have lost their jobs during the Covid-19 lock down that had particular implications for the service and catering industry. The same large-scale survey indicates that while international students tended to be more satisfied with their academic experiences during Covid-19 in the US research-intensive universities, they had significant concerns with health, safety and immigration issues (Chirikov & Soria, Citation2020). The most important concern related to managing their visa status and travel restrictions between the host and home countries (Chirikov & Soria, Citation2020). While there is very little research on international students’ experiences of Covid-19, the UK media further highlights international student experiences related to being treated as “cash cows” (BBC, Citation2021; Fazackerley, Citation2021), and their struggles with loneliness and isolation (Fazackerley, Citation2020). While not in the remit of this project, there is a clear need for research on international student experiences of the pandemic, both from the perspective of students who had opted for campus-based study and those who studied remotely from their home countries. What we do know from emerging work, however, is that studying during Covid-19 has been challenging for students, and it is likely that the issues related to study space, wellbeing and financial pressures have formed the core concern area for non-traditional students. It is therefore essential to consider what support is available to non-traditional students during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Student support as social network

There is extensive research on student support provision in HE, aiming to facilitate successful student progression through university education. The widely promoted approach to student support draws on Alan Tait’s (Citation2000, Citation2014) work, explaining support in relation to its cognitive, affective and systemic functions. The cognitive elements of support include the development of course materials, while affective aspects emphasise supportive learning environments and systemic features that prioritise administrative processes for student-centred education (Tait, Citation2000). Similar categorisations have been proposed by others, for instance, Brindley et al. (Citation2004) divide student support into teaching, advising and administrative support. These dominant views of support tend to approach students from non-traditional backgrounds as lacking academic and cultural resources necessary to succeed in HE. Correspondingly, the requirement of support practices is to “fix” these problems (Smit, Citation2012). Jacklin and Le Riche (Citation2009) problematise such functional views of support as encouraging a deficit-view of students. They promote a shift to “supportive” cultures, and define student support as “a socially situated, complex and multifaceted concept” (Jacklin & Le Riche, Citation2009, p. 735). Such an approach takes into account the intersection of student experience with their various other private and professional roles (Jacklin & Le Riche, Citation2009), placing equal attention on students’ social and academic worlds (Wilcox et al., Citation2005).

By drawing on Jacklin and Le Riche’s (Citation2009) idea of dynamic support, we propose that student support is best conceived as a form of social network. We define a social network as a set of relevant actors (persons or groups) connected to each other by one or more relations (Chua & Wellman, Citation2016; Daly, Citation2010; Marin & Wellman, Citation2011; Wellman, Citation1983, Citation2001). These relationships vary according to the frequency, direction, duration and nature of the exchange, all of which dictate the size of a network, the density of connections and the centrality of actors with certain students more connected to more people than the others (Kanagavel, Citation2019). While there is very little research on student support as social network, Kanagavel’s (Citation2019) monograph “The Social Lives of Networked Students” focuses on international students’ experiences of social support through the use of different media and face-to-face contact. The book argued that a technology-driven landscape has constructed new ways for students to make connections, enabling a flow of various support, e.g. study resources, information or acts of kindness (Kanagavel, Citation2019). Students bring to university a wide range of pre-existing social relations that are external to HE but are part of their social system (Dawson, Citation2008), highlighting the likely importance of friends and family in student support provision (Jacklin & Le Riche, Citation2009).

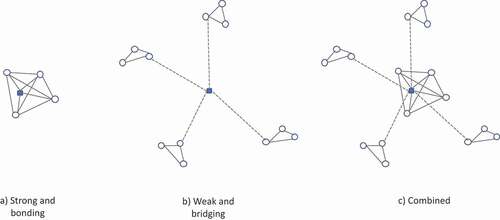

Approaching student support as a social network places the student at the centre of a set of personal connections (Kanagavel, Citation2019), drawing attention to their background, interactions and resources. From this perspective, we can then see how different types of networks affect likely support. Being part of a dense network, for instance, means having friends (or other ties) who are all familiar with one another, which can lead to a stronger sense of community (Marin & Wellman, Citation2011; Wellman, Citation1983). As a result, dense networks are often characterised by higher levels of trust and more exchanges of social support among members. Sparse relationships, while not fostering community (Wellman, Citation1983), also have uses. For instance, sparser networks provide opportunities to receive new information (whereas in dense networks existing news tends to be circulated). Hence, there may be an optimal mix of dense and sparse networks, which can be illustrated by conceiving relationships between people as representing weak or strong ties. As below shows, strong ties within groups enable individuals to connect to everyone within their network, helping bind people together as a support group. However, such ties are problematic for reaching beyond the immediate network. This means that weaker ties between networks can help spread information more widely by providing bridges from one dense group to another. Weaker ties can also help erode barriers, such as those caused by class or racial differences. A combination of both strong and weak ties can thus be optimal in terms of student support.

Figure 1. Strong and weak ties.Footnote3

It is common to consider resources that flow through networks as forms of social capital. Such capital might include the social norms accessible through networks, which provide individuals with an understanding of how to “play the game”. For instance, how to take advantage of the opportunities on offer or to navigate systems effectively. Bourdieu (Citation1986) in particular, perceived a strong link between a group’s social capital and their wealth (economic capital). Often, we can see this materialising as differences in the behaviours of advantaged and less advantaged groups as a result of divergences in how much social capital each possesses (Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1990). Alternatively, social capital can simply represent the resources we can access as a result of being in trusting relationships with others (Coleman, Citation1988). As a result, the bigger and more diverse student networks, the wider the potential resource base, including access to information or the ability to utilise other types of support. Coleman’s (Citation1988) approach therefore indicates that networks can often “spread” certain societal practices, by making resources available and spreading these across the networks. Of course, forging relationships is not necessarily straightforward and factors such as homophily and social background may prevent individuals building links and connecting with others. Nonetheless, by drawing on these notions of social capital theory our aim is to emphasise the potential of social networks in generating support and developing reciprocal supportive cultures in HE. In this case, social capital networks shape our understanding as to what constitutes appropriate relational behaviours and values. Such an approach recognises the resources that non-traditional students already have in their support networks, while also considering how to advance support using social network perspectives.

Research approach

Between July and October 2020, all three authors conducted individual interviews with 10 social sciences Year 2 students studying at Durham University, which is an elite research-intensive UK university. As this was an exploratory project (Yin, Citation2018), participants were sought via an open call through various email lists, including programme lists and “first generation” group email lists from within the social sciences; the sample is therefore respondent-driven (Heckathorn, Citation1997). The open invite was sent to all students with an emphasis that we particularly welcome students from diverse social backgroundsFootnote4 – the focus on “non-traditional” was a result of the sample who came forward and how students described themselves (see for the categories of self-identification). Both the programmes and the first-generation groups have a strong international presence, and it therefore made sense to interview both home and international students. Durham University provides an interesting context as it is centred around a “collegiate system”, meaning that student support tends to be provided academically by departments and pastorally by colleges, although in reality there is cross-over. Furthermore, Durham is a university town meaning that the town and the university are one combined space. During term-time, therefore it can be dominated by students. However, we note that this study only included social science students due to its limited scope and resources, and students from science disciplines may have had different experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic, related study spaces and support available. This might be particularly the case as the pandemic significantly disrupted the lab-based study approaches that are common to the science subjects.

Table 1. Participant profiles

Each interview took place via video-conferencing, and on average lasted for 40 minutes. All were audio-recorded and transcribed semi-verbatim by the three authors. Following ethical guidance from our institution and BERA (Citation2018), prior to the interviews, students were given consent forms, project information, and the opportunity to ask questions; they were also informed they had the right to withdraw their participation at any point during the process. The interviews were semi-structured such that there was room to adapt to students’ responses, yet the focus remained on the project’s aims. The purpose of the interviews was twofold: a) to identify a range of support actors that students access for academic and wellbeing purposes and b) establish how these differed compared to (pre-Covid) campus experiences. As such, questions focused on support and experiences both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Following transcription, a process of thematic analysis was applied to the data. Inductive analysis was initially used by all three authors to provide an individual categorisation of responses, with codes allocated to individual lines or turns of speech, or larger segments of text. Following this initial coding, a process of joint reflection and interpretation was undertaken to enable the research team to consider our understanding of the data (Robson, Citation2002). Hence, the flow between inductive and deductive coding (Merriam, Citation2009), enabled space for students’ elucidations, whilst maintaining a focus on the research purpose. The relationships between the codes were then assessed and mid-level codes were built until all initial codes could be adequately explained conceptually (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Additionally, following a social network approach (Perry et al., Citation2018), we identified core support actors around individual students’ experiences and interactions. The final overarching codes included: student background (including subcodes: first generation, working class, mature student, access course experienced, international student), study spaces (including subcodes: library, department, students’ union, college, student accommodation, campus cafés, home), issues experienced during Covid-19 (including subcodes: stress, anxiety, illness, study space, family disruption, technological issues), influential wellbeing support actors (including subcodes: family, siblings, parents, friends, GP, tutors/academics) and influential academic support actors (including subcodes: course friends, tutors/academics). This paper focuses particularly on the codes related to academic and wellbeing support actors, while referring to social background, study spaces, and issues experienced as and when relevant to set a context for the support interactions.

From the analysis, it was evident that all project participants – including both home and international students (see ) – identified or could be classified as “non-traditional” HE students (Christie, Citation2007). Students’ self-identification arose during the interview process or it was already known (due to the first-generation group). The first question we asked during the interview was “tell me how you ended up attending Durham University”; this was often probed to explore relations to the family.

As regards the participants’ self-identification, phrases such as “I’m obviously working class” (Lisa) and “I’m from a working-class background” (Michael) were used to express one’s socio-economic status. Similarly, the self-identification of being a northerner was highlighted: “like myself being from the North, I didn’t wanna go down South” (Laura). More commonly, however, the students interviewed described themselves as being among the first generation to go to university, which was characteristic of both the international and home student participants. As in the existing research (Meuleman et al., Citation2015; O’Shea, Citation2014, Citation2015; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019), the students highlighted a lack of family understanding of HE that made their transitioning to university stressful: “there was nowhere you could get advice or anything” (Lisa) and “[parents] really don’t know about how stressful it is in university” (Jenny). Among the participants, two students also emphasised the role of access courses in enabling their progression to university. These included a mature student with caring responsibilities (Kate) and an international student who defined herself as from “a lower middle class” (Kelly).

The participants’ accounts of themselves demonstrate how they positioned their student identity in relation to a variety of non-traditional characteristics: working class, first generation, mature, and access course experienced. They defined themselves as different and lacking expected types of economic, social and cultural capital in a Bourdieusian sense (Bourdieu, Citation1986, Citation2006). It may be the case that students felt it important to emphasise their social background as the institution they are attending is an elite university, and where the majority of students are from more affluent family backgrounds. Existing research has highlighted that non-traditional students tend to feel marginalised in elite universities (Coulson et al., Citation2018; Reay, Citation2018b).

Our results presented in the next section are therefore from an exploratory project that provided an in-depth insight into non-traditional student experiences and support during the Covid-19 pandemic. We acknowledge the limitations of a small and self-selected sample and remain cautious over generalisations to the wider university sector. It is possible that a comparative group of “traditional” students may have provided results with a clearer contrast. We therefore suggest that further comparative work could be carried out on a larger sample, within similar and more diverse universities. Moreover, this may include both international and home students, particularly as international student numbers are expanding within UK universities (OECD, Citation2020). Our results below therefore do not seek to generalise to all non-traditional student experiences; instead they are a catalyst for (re)considering how student support can be viewed. The findings sections start by outlining the key issues related to the students’ study space during the Covid-19 pandemic, and then move on to trace and discuss the academic and wellbeing support actors as experienced by the students interviewed.

Covid-19 and the study space

The students interviewed found their experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic stressful. Phrases such as “I felt more stress than I usually would during a typical university term” (Jane), and “I’m crying like almost every day, but I don’t know why” (Kelly) were common to the participants. Such accounts of mental distress have been highlighted by emerging research worldwide (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020; Son et al., Citation2020) with an indication that non-traditional students are likely to experience greater levels of stress during the pandemic than their more affluent counterparts (Chirikov et al., Citation2020; Soria et al., Citation2020). The main stressors for the participants related to the sudden shift from campus-based university experience to moving back home, which caused a sense of isolation and raised concerns about appropriate study space. For some students (Jenny, Laura, Anna and Michael) being isolated from their friends was a concern:

I have quite a lot of friends actually like the whole college corridors are my friends. I have friends from other courses as well or like from the same course. So usually I will, um have meal with them, talk to them and study with them together. But after this [Covid-19], we don’t really talk much because it’s, you know it’s quite inconvenient online. (Jenny)

While non-traditional students are often portrayed as being less involved in campus life (Bathmaker et al., Citation2016; Reay, Citation2018a; Rubin & Wright, Citation2017), it is expected that moving “back home” (as was the case with our participants) constitutes a significant change in their study environment and access to resources. It may also be the case that non-traditional students from Durham University were already more likely to participate in campus life due to its collegiate nature and significant extracurricular programme. The change to remote study may have constituted a more influential change for the students we engaged with. We therefore urge the readers to interpret the findings within the particular Covid-19 and institutional context.

While Kate, as a mature student, was less engaged in social life on campus like many other mature students (Hope & Quinlan, Citation2020), she still recognised that being off campus was going to affect her ability to cope with social interactions and “make it harder going back”. Such emphasis on social interaction may again be particularly characteristic to collegiate universities that set the expectations for students to take part in various extracurricular and social activities (Eamon, Citation2016; Reay et al., Citation2010). While participants emphasised the negative change in their social life, the main concerns related to study space. The issues ranged from having a suitable “desk space” (Lisa, Sophie) to sharing and negotiating family spaces (Jane, Michael, Kate, Jenny, Laura and Lisa):

My mum had to use my study space sometimes ‘cause my study space is kind of like the most private area, and my mum, she works for the NHS [National Health Service], so she had a few quite confidential calls, so there were a few like interruptions, because she would have to use my kind of little study alcove to take her calls. (Michael)

International students emphasised slightly different issues with their study space. For example, Jenny, a first-generation student from Malaysia, explained that her parents did not understand her study needs and placed expectations on family socialising. This resulted in her leaving her house to study at her friend’s. Furthermore, the time difference and its effects on the rest of the family was emphasised by Lucy: “my parents are saying ‘you are so disturbing’, because I need to, you know, stay up late and study”. It is evident from the data above that the study space has become a core issue for students interviewed, echoing the environmental challenges highlighted by global research on student experiences of Covid-19 (Aguilera-Hermina, Citation2020; Aristovnik et al., Citation2020). The study space for non-traditional students appears to be of particular importance, and students themselves note that the space in their homes is limited, often needing to be shared with other household members. All students mentioned how they missed the university library as an important learning environment during term-time. Students were also aware of the disadvantage their home circumstances caused as vividly illustrated by Lisa:

‘cause obviously the middle class they go home, they’ve got nice offices, top notch Wi-Fi, they have got everything they need, like at home library, or something I don’t know. So I think the university assumes everyone is like that rather than acknowledging that not everyone has that privilege. (Lisa)

The removal of the university campus during the Covid-19 lockdown, thus also removed social and spatial structures, that may have acted as equalisers in terms of immediate study environment. This amplified the role of students’ personal resources in managing their studies. Such intersections with personal background become further evident when tracing students’ support networks.

Tracing student support networks

An ego-centric approach to social networks (Perry et al., Citation2018) enabled students to reflect on their interactions with available academic and wellbeing support. We will start by outlining the actors that students had less engagement with during the pandemic, moving on to introducing the core actors of family members and fellow students. These examples provide a rich insight into the participants’ support networks, and it is expected that the findings can and should inform larger scale research and discussions on non-traditional student experiences and support provision.

Limited engagement with formal university services

There was a limited mention of formal university support in student interviews. It was evident that the students interviewed had little contact with formal support even prior to Covid-19; however, the pandemic seemed to have amplified their distance from the support services available. Reflecting on their experiences of the pandemic, students emphasised: “I haven’t used any of them” (Jenny), and “No, generally, I just sort of keep myself to myself” (Lisa). The only time formal support was mentioned was in relation to English language support for international students (Lucy) and seeking college advice on accommodation (Jenny). Interestingly, Anna highlighted her engagement with college wellbeing services for the purposes of social interaction: “I did go to a couple of sessions during the lockdown. It’s just because I wanted to socialise with people more, not necessarily with asking for help for well-being”. While participants tended to distance themselves from university support and opportunities available like many other non-traditional students (Coulson et al., Citation2018; Reay, Citation2018b), there was a continuing emphasis on social interaction as illustrated by Anna’s account. It may be that the Covid-19 lockdown had caused a sharp contrast in student experience, or it was a particular characteristic of a collegiate university, making students emphasise the absence and importance of campus life.

Other formal support related to mental health support, which was outside the university’s support services:

…so I reached out to the GP about the mental health and stuff, but not to uni, ‘cause I sort of felt there’s not much what are they gonna do? I wasn’t sure what they could do like, I was better off going to professional, and obviously as far as I was aware, the university is closed. Everyone’s gone home, so I wasn’t sure who was about, what was still going on (Lisa)

Lisa highlights serious issues related to “administrative functions” of support (Tait, Citation2000, Citation2014). It is evident that by not knowing how to seek help and experiencing university as being “closed”, it raises concerns about the university’s ability to reach students in need. It also creates a sense of weak ties (Jackson, Citation2019; Kanagavel, Citation2019) between students and formal support actors. It is therefore unsurprising that the support network students developed with academics, family members and peers tended to be personalised and built on their prior relations and resources (Dawson, Citation2008; Jacklin & Le Riche, Citation2009).

Personalised engagement with academics/tutors

Similarly to formal services, there was limited engagement with academic staff. However, the participants strongly expressed the need for this to increase. Communication with academic staff was rather chaotic due to new circumstances that both staff and students found themselves in, and the phrases such as “lecturers didn’t really know what was going on themselves, so they couldn’t really provide that much support” (Jane) were common. As a new type of communication was required, the students primarily engaged with academics where they had already established stronger relationships, demonstrating the importance of trusting relations in social networks (Coleman, Citation1988) during crises such as Covid-19. However, it is essential to note that students spoke about teaching staff in relation to wellbeing rather than academic support. For example, Lucy describes significant mental health support from an academic during her self-isolation period:

We talked for like 2 hours, and she gave me a lot of advice like, ‘You could do some exercise or you could do some yoga before you go to bed and read something to make you feel better, like some poem, to calm you down’. (Lucy)

While Michael and Jane addressed academic matters, their core focus was also on wellbeing support: “So when I had a call with Peter [module tutor], we kind of just had a chat about how each other was coping with all the changes” (Michael) and “It’s nice to hear your lecturer is saying like, ‘You need to put your wellbeing first’” (Jane). It can be argued that academics within the student support networks were primarily described in relation to wellbeing support. These interactions were rather informal, relying on pre-existing relationships established with specific academics. Furthermore, the connections operated on an ad hoc basis (Kanagavel, Citation2019) rather than being systemic, thus making students highlight and value the single memorable encounters they had.

As the participants in this study were Year 2 students, it raises questions around the extent to which first-year students with no prior engagement with their tutors could acquire support through staff–student interactions. The productive nature of social capital as Coleman (Citation1988) explained, is reflected in the informal relationships that students develop through their day-to-day campus-based interactions. Furthermore, it shows that social capital is clearly defined by “its function […] facilitating certain actions of actors” within the opportunities available (Coleman, Citation1988, p. 20). The social capital that participants had developed during their first year of studies reflected in trusting relations with key academics and resulted in highly valued wellbeing support.

Core actors: family members and wellbeing support

As noted earlier, family members were often portrayed as distracting to academic studies as the shared space needed to be negotiated. The issues common to first-generation, working class and mature students related to the available resources and the limited household space (Meuleman et al., Citation2015; O’Shea, Citation2014, Citation2015; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019). However, the findings demonstrate that it is important not to underestimate the wellbeing support students received from their families. This resourceful aspect of families is particularly significant as many of the participants were the first in their family to attend university (see ), enabling us to question the common deficit views of non-traditional students. It also demonstrates how social capital in support networks can take various forms, creating a strong sense of belonging and care (Coleman, Citation1988).

The support received from family members ranged from small gestures such as “having my mum around asking if I want a cup of tea or anything” (Michael) and “my parents making my food and stuff […] and maybe like, do you want, you know, a cup of tea” (Laura), to forms of support that had significant effects on students’ mental health and wellbeing. Students highlighted how they could talk to their parents about difficult experiences although as Kelly outlines below, there was a tendency to exclude academic details. This was to avoid worrying parents or students thought their parents may not understand if they did not have HE experience (Meuleman et al., Citation2015; O’Shea, Citation2016):

…when I was too anxious and like, I worry whether I can finish it on time like, I would talk to my family. But I don’t really say something like, uh, about academic things […] I just say maybe I’m a little bit stressed or I want them to comfort me (Kelly)

It was rare for these students to mention academic support from their families, and this was only done where direct or extended family members had attended HE themselves, echoing the past research (see Meuleman et al., Citation2015). In cases where academic support was available, it was particularly valued during the pandemic as illustrated by Jane who lived with her father and brother (employed in manual jobs), but whose mum had been to university later in life and who had an uncle with a university degree:

I had quite a few like projects to complete during Easter, which is during lockdown, like the probably the worst part of lockdown, and I needed quite a bit of support for that, but I didn’t necessarily go to the university. I just like asked like my family members for support like my mum who later went on to do the university degree and my uncle as well, so they were my main like support really as they understand how hard it is normally, but especially for a pandemic, they really sympathised. (Jane)

Jane’s account above illustrates the crucial role that family members with HE experiences can play in students’ academic and wellbeing support, particularly in terms of easing academic stress and acting as mentors and role models (O’Shea, Citation2014, Citation2015; O’Sullivan et al., Citation2019). In such cases, it is likely that the support received combines both academic and wellbeing advice, resulting in an influential support group that is high density (Jackson, Citation2019) and shadows any formal university support. Such findings and scholarly speculation deserve further investigation to be able to confirm the potential significance of family in non-traditional student support.

Core actors: fellow students and academic/wellbeing support

Fellow students were described as essential for both academic and wellbeing support, particularly for their similar experiences during Covid-19. This highlights the importance of peer networks in student support provision as going through a similar experience appears to be a strong connecting component. Research on student support has demonstrated that “being in the same boat” has a positive effect on the student experience (Jacklin & Le Riche, Citation2009). It also compensates for the lack of academic support that first-generation students tend to have in their immediate social circles. However, it is also important to note that the students had a small selection of peers they engaged with and therefore perceived as close friends. The academic examples of peer support mainly included exam preparation:

Yeah, I have two friends, doing [a degree programme], and I have friend who does the same courses as me. So that was quite good to have her, and she was like we were sharing when revising for exams and stuff which was nice. (Jane)

…my friend and I study the same module. She’s a good student, so sometimes we can talk about our work or essay (Kelly)

Such peer support is clearly reciprocal and rather intimate in terms of close friendship groups. It is related to students’ everyday activities and interactions (Kanagavel, Citation2019) and demonstrates how social capital in student support networks is reciprocal and enabling (Coleman, Citation1988). It promotes a culture of trust and mutual benefit for common objectives (Coleman, Citation1988), which in the case of interviewees was related to passing exams and providing wellbeing support, as becomes evident below:

…my friends in the UK, some of them feel a little bit depressed and yeah because most of international students have gone back home, and my friend didn’t get the plane ticket, and she was just really depressed and we FaceTime a lot. (Lucy)

Prior research has emphasised that international students tend to develop particularly strong friendship groups based on their shared experiences of studying abroad (Montgomery & McDowell, Citation2009). A very different account, however, is provided by Kate, who as a mature and commuting student had less social contact with peers: “I don’t really interact too much on the social side […] I just get the age gap is maybe just a little bit too much”. This has also resulted in less contact with other students during the pandemic, creating a stronger sense of isolation and indicating that HE interactions in her experience primarily centred around academic studies (Hope & Quinlan, Citation2020).

Conclusion

This project has provided an in-depth engagement with non-traditional student experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic and the support available to these students. This small dataset allows for a rich study of experience, but limits generalisations to students from different social backgrounds, study levels and disciplines, the university itself, or the wider sector. However, the dataset clearly draws attention to the heightened levels of anxiety and stress, as well as issues related to suitable study space in home environments. While these experiences are concerning, they echo the emerging research on students during the Covid-19 crisis (see Aguilera-Hermina, Citation2020; Aristovnik et al., Citation2020; Chirikov et al., Citation2020; Son et al., Citation2020). What makes this project unique, however, is its scholarly insight into the support that the students developed and engaged with to address their academic and wellbeing challenges. Our findings demonstrate that student support networks were rather small in scale but dense in contact and interaction, and they primarily centred around family and fellow students. The family was particularly important for wellbeing support which ranged from small gestures (a cup of tea) to an opportunity to share and reflect on one’s stressful experiences. While most participants in this study were first-generation, it is unsurprising that family members were seen as less able to provide academic support. It was the fellow students who became the primary academic support, but the findings also indicate that such peer support was established between small friendship groups who shared trust and care. Our findings demonstrate the productiveness of social capital (Coleman, Citation1988) and the potential for close interactions that lead to friendships and valuable support.

This article highlights the importance of family and friendship interactions in non-traditional student support networks, encouraging us to question the dominant deficit views of non-traditional students that often portray their family background as lacking essential qualities for successful university study. While it is important to recognise the resourcefulness of “non-traditional families”, particularly for student wellbeing, the findings still draw attention to the lack of systemic institutional support in student networks and the effects it may have on some disadvantaged students. From our sample of student interviews, we have seen that there was a limited presence of university support actors in their networks, e.g. formal support services, academics and colleges. The latter is particularly important for collegiate systems like Durham University, where colleges are hubs for social activity and pastoral care. As our sample has limitations, we recommend further research exploring “non-traditional” student networks, that draws from wider universities both within and beyond the college/elite system.

Regardless, we highlight the importance of acknowledging and drawing on the strengths that students have in their immediate support networks. Yet this study also suggests the possibility of enlarging support networks through awareness raising of available support, institutional interventions (e.g. peer networks and mentoring schemes) and investment in wellbeing and mental health services. Conceptualising and developing student support as social networks is potentially vital in times of crisis, where individual and societal wellbeing heavily depends on reciprocity: that is, being able to provide and access support. Emphasis on support as comprising social networks offers a much-needed lens to recognise and then support the interconnected patterns of relations between individuals and the resources available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The representative organisation for the UK’s universities since 1918.

2. The survey involved 30,697 undergraduates from 9 research intensive universities in the US.

3. The figure has been produced by Chris Brown for illustrative purposes.

4. The invite included examples of diversity such as first generation, lower socio-economic background, international/home student status, students with disabilities, mature students, care leavers and estranged students. We noted that the list is non-inclusive and welcomed student participation from all backgrounds.

5. Anglo-Saxon pseudonyms were chosen for international students to reflect their use of first names in the university.

References

- Aguilera-Hermina, A. P. (2020). College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Research Open. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011

- Antonucci, L. (2016). Student lives in crisis. Deepening inequality in times of austerity. Policy Press.

- Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208438

- Bathmaker, A., Ingram, N., Abrahams, J., Hoare, A., Waller, R., & Bradley, H. (2016). Higher Education, social class and social mobility: The degree generation. Palgrave Macmillan.

- BBC. (2021). Covid: International students seek compensation from UK government. Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-56250975

- BERA. (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown, & A. S. Wells (Eds.), Education, culture, economy and society (pp. 16–58). Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2006). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In D. B. Grusky & S. Szelényi (Eds.), Inequality: Classic readings in race, class, and gender (pp. 257–271). Westview Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education. society and culture (Vol. 4). Sage Publications.

- Brindley, J. E., Walti, C., & Zawacki-Richter, O. (2004). The current context of learner support in open, distance and online learning: An introduction. In J. E. Brindley, C. Walti, & O. Zawacki-Richter (Eds.), Learner support in open, distance and online learning environments (pp. 9–27). Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky.

- Cena, E., Burns, S., & Wilson, P. (2021). Sense of belonging, intercultural and academic experiences among international students at a university in Northern Ireland. Journal of International Students, 11(4). https://ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/2541

- Chirikov, I., & Soria, K. M. (2020). International students’ experiences and concerns during the pandemic. Center for Studies in Higher Education. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43q5g2c9

- Chirikov, I., Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., & Jones-White, D. (2020). Undergraduate and graduate students’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Centre for Studies in Higher Education. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw

- Christie, H. (2007). Higher education and spatial (im)mobility: Nontraditional students and living at home. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(10), 2445–2463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a38361

- Chua, V., & Wellman, B. (2016). Networked individualism, East Asian style. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Communication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.119

- Chung, E., Turnbull, D., & Chur-Hansen, A. (2017). Differences in resilience between ‘traditional’ and ‘non-traditional’ university students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417693493

- Clow, D. (2020). What should universities do to prepare for COVID-19 coronavirus? Wonkhe. Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://wonkhe.com/blogs/what-should-universities-do-to-prepare-for-covid-19-coronavirus/

- Clune, A. (2020). Using technology to cope with Covid-19 on (or off) campus. Wonkhe. Retrieved March 13, 2020, from https://wonkhe.com/blogs/using-technology-to-cope-with-covid-19-on-or-off-campus/

- Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Coulson, S., Garforth, L., Payne, G., & Wastell, E. (2018). Admissions, adaptations and anxieties: Social class inside and outside the elite university. In R. Waller, N. Ingram, & M. Ward (Eds.), Higher education and social inequalities: University admissions, experiences and outcomes (pp. 3–21). Routledge.

- Crozier, G., Reay, D., Clayton, J., Colliander, L., & Grinstead, J. (2008). Different strokes for different folks: Diverse students in diverse institutions. Research Papers in Education, 23(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520802048703

- Daly, A. (2010). Mapping the terrain: Social network theory and educational change. In A. Daly (Ed.), Social network theory and educational change (pp. 1–16). Harvard Education Press.

- Dawson, S. (2008). A study of the relationship between student social networks and sense of community. Educational Technology & Society, 11(3), 224–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23013

- Eamon, M. (2016). Constructing a collegiate compass. In T. Burt & H. M. Evans (Eds.), The collegiate way: University education in a collegiate context (pp. 61–74). Sense Publishers.

- Eringfeld, S. (2020). Higher education and its post-coronial future: Utopian hopes and dystopian fears at Cambridge University during Covid-19. Studies in Higher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1859681

- Fazackerley, A. (2020). ‘I only see someone if I do my laundry’: Students stuck on campus for a Covid Christmas. The Guardian. Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/dec/05/students-stuck-on-campus-for-a-covid-christmas

- Fazackerley, A. (2021). ‘Treated like cash cows’: International students at top London universities withhold £29,000 fees. The Guardian. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/mar/13/treated-like-cash-cows-international-students-at-top-london-universities-withhold-29000-fees

- García-Peñalvo, F. J., Corell, A., Abella-García, V., & Grande, M. (2020). Online assessment in higher education in the time of COVID-19. Education in the Knowledge Society, 21, 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23013

- Hale, K., Rivas, J., & Burke, M. G. (2020). International students’ sense of belonging and connectedness with US students: A qualitative inquiry. In U. Gaulee, S. Sharma, & K. Bista (Eds.), Rethinking education across borders (pp. 317-330). Springer.

- Heckathorn, D. D. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2), 174–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3096941

- Hope, J., & Quinlan, K. M. (2020). Staying local: How mature, working-class students on a satellite campus leverage community cultural wealth. Studies in Higher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1725874

- Hordosy, R., & Clark, T. (2018). Beyond the compulsory: A critical exploration of the experiences of extracurricular activity and employability in a northern red brick university. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 23(3), 414–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2018.1490094

- Hordosy, R., Clark, T., & Vickers, D. (2018). Lower income students and the ‘double deficit’ of part-time work: Undergraduate experiences of finance, studying and employability. Journal of Education and Work, 31(4), 353–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2018.1498068

- Husky, M. M., Kovess-Masfety, V., & Swendsen, J. D. (2020). Stress and anxiety among university students in France during Covid-19 mandatory confinement. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102, 152191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152191

- Jacklin, A., & Le Riche, P. (2009). Reconceptualising student support: From ‘support’ to ‘supportive’. Studies in Higher Education, 34(7), 735–749. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802666807

- Jackson, M. (2019). The human network: How we’re connected and why it matters. Atlantic Books.

- Kanagavel, R. (2019). The social lives of networked students. Mediated connections. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lederman, D. (2020). Evaluating teaching during the pandemic. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/04/08/many-colleges-are-abandoning-or-downgrading-student-evaluations

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

- Marginson, S. (2020). The relentless price of high individualism in the pandemic. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1392–1395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1822297

- Marin, A., & Wellman, B. (2011). Social network analysis: An introduction. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social network analysis (pp. 11–25). Sage Publications.

- McKavanagh, M., & Purnell, K. (2007). Student learning journey supporting student success through the student readiness questionnaire. Studies in Learning, Evaluation, Innovation and Development, 4(2), 27–38. https://eprints.usq.edu.au/3299/4/SLEID-RRP-article3MMcKavanaghKPurnell.pdf

- McKay, J., & Devlin, M. (2016). ‘Low income doesn’t mean stupid and destined for failure’: Challenging the deficit discourse around students from low SES backgrounds in higher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(4), 347–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1079273

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Meuleman, A. M., Garrett, R., Wrench, A., & King, S. (2015). ‘Some people might say I’m thriving but … ’: Non-traditional students’ experiences of university. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(5), 503–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.945973

- Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

- Montacute, R. (2020). Social mobility and covid-19. Implications of the Covid-19 crisis for educational inequality. Sutton Trust. https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-and-Social-Mobility-1.pdf

- Montgomery, C., & McDowell, L. (2009). Social networks and the international student experience: An international community of practice? Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(4), 455–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308321994

- Nambiar, D. (2020). The impact of online learning during COVID-19: Students’ and teachers’ perspective. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(2), 783–793. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25215/0802.094

- O’Shea, S. (2014). Transitions and turning points: Exploring how first-in- family female students story their transition to university and student identity formation. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(2), 135–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.771226

- O’Shea, S. (2015). Filling up silences—first in family students, capital and university talk in the home. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 34(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2014.980342

- O’Shea, S. (2016). Avoiding the manufacture of ‘sameness’: First-in-family students, cultural capital and the higher education environment. Higher Education, 72(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9938-y

- O’Sullivan, K., Robson, J., & Winters, N. (2019). ‘I feel like I have a disadvantage’: How socio-economically disadvantaged students make the decision to study at a prestigious university. Studies in Higher Education, 44(9), 1676–1690. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1460591

- OECD. (2020). Education at a glance 2020. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2020_69096873-en#page1

- Perry, B. L., Pescosolido, B. A., & Borgatti, S. P. (2018). Egocentric network analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Raaper, R., & Brown, C. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic and the dissolution of the university campus: Implications for student support practice. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), 343–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0032

- Reay, D. (2018a). Working class educational transitions to university: The limits of success. Journal European Journal of Education, 53(4), 528–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12298

- Reay, D. (2018b). A tale of two universities. In R. Waller, N. Ingram, & M. Ward (Eds.), Higher education and social inequalities: University admissions, experiences and outcomes (pp. 83–98). Routledge.

- Reay, D., Crozier, G., & Clayton, J. (2010). ‘Fitting in’ or ‘standing out’: Working- class students in UK higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902878925

- Robson, C. (2002). Real world research. Blackwell.

- Rubin, M., & Wright, C. L. (2017). Time and money explain social class differences in students’ social integration at university. Studies in Higher Education, 42(2), 315–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1045481

- Smit, R. (2012). Towards a clearer understanding of student disadvantage in higher education: Problematising deficit thinking. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.634383

- Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e21279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

- Soria, K. M., & Horgos, B. (2020). Social class differences in students’ experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic. Centre for Studies in Higher Education. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1fgQdrXCyquMrEKzGn_5ZaSVrF8zXpvtI6Rn3-RINfXs/edit#heading=h.nwaknanyns7x

- Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., Chirikov, I., & Jones-White, D. (2020). First-generation students’ experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic. Centre for Studies in Higher Education. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/19d5c0ht

- Tait, A. (2000). Planning student support for open and distance learning. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 15(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/713688410

- Tait, A. (2014). From place to virtual space: Reconfiguring student support for distance and e-learning in the digital age. Open Praxis, 6(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.6.1.102

- Tarman, B. (2020). Editorial: Reflecting in the shade of pandemic. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 5(2), i–iv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.46303/ressat.05.02.ed

- Taylor, Y., & Scurry, T. (2011). Intersections, divisions, and distinctions. European Societies, 13(4), 583–606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2011.580857

- UK Government. (2020). Widening participation in higher education: 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/widening-participation-in-higher-education-2020

- Universities UK. (2020). Achieving stability in the higher education sector following COVID-19. https://universitiesuk.ac.uk/news/Documents/uuk_achieving-stability-higher-education-april-2020.pdf

- Wahab, A. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Studies, 10(3), 16–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

- Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

- Wellman, B. (1983). Network analysis: Some basic principles. Sociological Theory, 1, 155–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/202050

- Wellman, B. (2001). Physical place and cyberplace: The rise of personalized networking. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(2), 227–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00309

- Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie‐Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first‐year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340036

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.