ABSTRACT

Based on related academic and semi-academic discourse, this paper aims to investigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on important actors and their expectations in the higher education (HE) sector. As open organisations, higher education institutions (HEIs) are influenced and shaped by different stakeholders’ numerous and often controversial demands. While HEIs strive to meet key actors’ needs, these expectations have a determinative role in the future of HEIs. Therefore, the future-oriented horizon scanning method was used for mapping the explicit demands of actors and for analysing alterations in expectations due to the pandemic. The horizon scanning showed that one of the most pressing expectations of HEIs in Central-Eastern Europe (CEE) was digitalisation even before the pandemic. Due to the pandemic, the awaited digitalisation in HE was realised within a few weeks, and it affected all actors. The tangible daily experience of the digital mode of education changed the priorities and expectations of the actors. In addition, this unexpected situation brought to the surface HEIs’ hidden potentials, resources and responsibilities. Although the role of digitalisation in the future of HE is clearly manifested, the impacts of social restrictions as well as the effects of the digitalisation of learning and life in general were perceived primarily in the field of socialisation. As a result, the need for socialisation has increased. The article highlights the dynamic interconnection between digitalisation and socialisation, and the changing expectations and voices of stakeholders, which should be considered when HEIs choose their future paths in the post-COVID-19 era.

Introduction

In the past decades, there has been increasing criticism concerning higher education (HE) regarding its capability to prepare students to be capable members of knowledge-based society and also to be useful and successful employees and citizens (Gumport, Citation2000; Maassen, Citation2014). In order to respond to these challenges, higher education institutions (HEIs) increasingly focused on the expectations of their external stakeholders (labour market, government, funders, society, etc.).

Regarding these demands, one of the ways to devise relevant response strategies is to follow global leaders’ examples. Accordingly, knowing and following global trends in HE have become a central topic in the sector in Central and Eastern European (CEE)Footnote1 countries. However, global influences are certainly modified by national traditions, and also by the requirements and special features of the local environment. This multifactorial interplay should be taken into account when studying the impact of COVID-19. Therefore, we constructed our theoretical basis on this broader context. At the same time, our analysis focuses mostly on the interpretation of the CEE-specific characteristics of COVID-19 effects in HE, which are the results of the above-mentioned interaction between global and local factors.

Due to the pandemic, radical changes had to be implemented worldwide within a very short time with the help of improvised crisis management. At the same time, in the situation characterised by total lockdown, local and internal responsibilities of universities came to the limelight. Thus, HEIs were forced to focus on their students, their teachers, and their internal processes in order to continue education provision in the new digital context. The global pandemic has been handled differently by HEIs according to their immediate environments and specificities.

Altered circumstances and changes in the operation of HEIs prompted the awakening of the role of university in socialisation: namely, HE is not only about knowledge transfer, grading and certification, but it is also a place of learning for becoming an informed citizen, a prepared future employee with professional norms, and a person with both intellectual and social skills.

Therefore, our research aims to show the complex and dynamic interconnection of socialisation and expanded digitalisation that emerged in the COVID-19 related academic and semi-academic discourse and wishes to present examples concerning this interconnection drawing on examples from the CEE countries. Changes in these circumstances are closely connected to the different stakeholder groups affected. In order to help HEIs to move forward, it is important to take into account the effects of the pandemic on the main stakeholders, and it is likewise necessary to map their newly emerging demands. For reaching this research aim, the future-oriented horizon scanning method seemed a proper choice as the method is capable of identifying the most extensively discussed effects of the pandemic in recent academic and semi-academic discourse.

Accordingly, within the conceptual framework of the present research, the most important theories in connection with the open institutions, interrelations between digitalisation and socialisation will be introduced first. After that, the horizon scanning method is presented. Next, the results of our scan are discussed in detail focusing on the effects of the pandemic, on the changing expectations of the actors concerned, and on the comparison of the situation before and after the pandemic. After a discussion that considers consequences and dilemmas, a short conclusion is provided.

Conceptual framework

Universities are open organisations (Scott, Citation2003) in that they constantly take into account the needs of their main stakeholders, and maintain competitive or collaborative relationships with other actors of the sectors involved. The interpretation of HEIs as complex social actors (Jongbloed et al., Citation2008) embedded in an intricate social environment is crucial when we think about the future role and responsibilities of such institutions. This is especially so because the requirements of different stakeholder groups are numerous and often contradictory (Maassen, Citation2000). Due to continually surfacing new tasks, roles, and responsibilities, HEIs suffer from what one might call “mission overload” (Brennan & Teichler, Citation2008). In order to cope with this mission overload, HEIs have to map not only their stakeholders and their interests but also the challenges and opportunities which shape the present and the future of the educational sector.

The stakeholders of a HEI can be grouped in several ways (Jongbloed et al., Citation2008; Mainardes et al., Citation2010; Mitchell et al., Citation1997). During our research, in the ecosystem in and around HE, the internal-external dimension emerged as a constitutive distinction between different actors. Furthermore, regarding the future challenges of HEIs, it is important to understand the expectations of their internal stakeholders so that these stakeholders can be relied on when responses to the external requirements of fast-changing and uncertain environments are required. And vice versa, HEIs should pay attention to their internal stakeholders’ changes of expectations in relation to the transformations of the external ecosystem. Therefore, it is important to map future changes so that flexible, reliable, and cooperative stakeholder management could be developed.

Given this, in the following we will focus on two main fields of HE where considerable changes have occurred lately: the challenge of digitalisation and, in close relationship with it, socialisation. It should be noted that although there are many approaches and realizations to both digitalisation and socialisation, these terms are used as “umbrella terms” in this article. The chosen methodology and the broad interpretation are in harmony as both allow us to see as many new approaches as possible. Consequently, digitalisation includes e-learning, the usage of learning analytics, online/internet-based education, the use of ICT-tools, and so on. Through the broad interpretation of the term socialisation, we have tried to capture as many related elements, levels and aims of socialisation as possible in the context of digitalised education.

Digitalisation belonged to the most important trends before the pandemic as digitalisation has the power to change society and business (Bejinaru, Citation2013). In line with that, the importance of digital tools and platforms started to increase even before COVID-19 appeared (Gupta & Gupta, Citation2020). The achieved level of digitalisation in HE was different worldwide. In Central-Eastern Europe (CEE), digitalisation expanded mostly concerning administrative processes, although there have long been experimental (e.g. MOOC) courses and the testing of ICT-based methodology has also been ongoing, but full digital programmes or universities hardly ever existed. In most cases, teachers optionally incorporated digital devices, the Internet, applications in their classrooms. Thus, education was realised basically in a face-to-face manner.

In turn, other areas of the world had richer experiences with and more extensive knowledge of highly digitalised education at universities before the pandemic. There were positive experiences which fuelled the expansion of digitalisation in other countries, too. Let us mention for example the overcoming of temporal and geographical barriers (Selwyn, Citation2014) or ensuring the provision of the continuous flow of information (Bejinaru, Citation2013). Among advantages, one can mention the following: increased cost-effectiveness and productivity (Rumyantseva et al., Citation2020) of digital education, more democratic interpretation of equal accessibility for different social groups (e.g. lower social status, minorities), increased opportunities of tailor-made, individual learning paths (Selwyn, Citation2014), and the flexibility and freedom of learning (Irwin & Berge, Citation2006). There are useful opportunities in learning analytics at both the individual and systemic levels (Selwyn, Citation2021). In addition, Bejinaru (Citation2013) claimed that digitalisation is the key for HEIs to exist in the future. Although, digitalisation is a widely discussed topic, these above-mentioned factors constitute pillars of an optimistic forecast in relation to the expansion of digitalisation.

At the same time, some challenges and important issues were also raised due to the more extensive experiences of digitalised HE. According to Cuban (Citation1993), the trend of digitalisation cannot transform education easily because educational systems with their centuries-old traditions and solidified structures are resistant. Therefore, the outcome of the interaction between digitalisation and education systems is uncertain. Furthermore, teachers, who embody the educational systems, play an extraordinary role in changes: they can facilitate or hinder processes, and they can also encourage or discourage one another (Carlsen, Citation2003). The success of digital solutions (ICT-tools, Internet, learning analytics, etc.) in education is strongly determined by the logic, philosophy and knowledge of the teaching staff (Fűzi, Citation2019; Selwyn, Citation2021; Williamson et al., Citation2020a). This is well exemplified by Wolff (Citation2013), who stated that the face-to-face presence of teachers and students permeates beyond the cognitive nature of education. Real meetings among people are unpredictable and spontaneous and this can cause unexpected changes and can inspire people, which is important from the perspective of socialisation (Marathe, Citation2018; Van Maanen & Schein, Citation1979). This instinctive milieu is irreplaceable in online environments even if interactive elements are used (Wolff, Citation2013). The absence of personal contact was emphasised by Magyari (Citation2010), who considers the lack of metacommunication a loss that leads to reduction of communication among teachers and students. Ollé (Citation2010) claims that one of the obstacles in the way of the digitalisation of HE is linked to teachers’ shared belief that personal contact has priority in education.

From a more critical point of view, however, we should take into account the risks of digital education. Irwin and Berge (Citation2006) state that the flexibility and freedom offered by online classrooms go hand in hand with growing anxiety and feelings of isolation. It was inevitable to recognise that only a small portion of the students have the high level of motivation and self-regulation that is necessary in Internet-based learning environments (Selwyn, Citation2014). Moreover, Selwyn (Citation2014, p. 26) mentions that “online education could perhaps even be seen as a form of spiritual alienation – i.e. alienation at the level of meaning, where conditions of good work become detached from the conditions of good character”, which is linked to the possibility of hiding or masking one’s real self as a participant of the learning process (Irwin & Berge, Citation2006). Williamson et al. (Citation2020a) expressed concerns about the expanding use of learning analytics. Not all kinds of knowledge taught in schools can be measured. In fact, too extensive incorporation of learning analytics can lead to pedagogical reductionism, which means that teachers (as well as students) focus only on measurable elements (Williamson et al., Citation2020a). This would be a great loss from holistic personal development. A further example of the negative impact of digitalisation is the neglect of basic human skills (Zawacki-Richter, Citation2021).

Beyond the approach focalising students as individuals, teachers also faced difficulties in community building. Lack of communities hinders the learning of social norms and decreases learning efficiency (Castellanos-Reyes, Citation2020; Irwin & Berge, Citation2006; Salmon, Citation2011, Citation2007; Selwyn, Citation2014; Shin, Citation2003). Based on the theory of social constructivism, a close connection is supposed to exist between social interactions, presence, and learning efficiency. Therefore, a large number of experiments aimed at improving learning achievement in digital environments through enhancing it with social elements. For the purpose of digital/online social knowledge construction, it is not enough to share a platform with others. Activities, valuable interactions (Serdyukov & Serdyukova, Citation2015), mutual stories, traditions, the “perception of group exclusivity” – as Irwin and Berge (Citation2006) phrase it –, and a community constitute the pillars of supportive reflections and constructive debates. The attainment of common goals informing each other can be realised only in communities (Sneyers & De Witte, Citation2018). Based on the results of a Community of Inquiry project, Castellanos-Reyes (Citation2020) mentions that social presence including real connections among peers and participation through one’s full personality is one of the three keys of an effective online learning experience. Salmon (Citation2011, Citation2007) went further and developed a process and techniques of building effective online learning communities. She draws attention to creating common ceremonies, showing examples of critical thinking and expressing critique in a constructive way. Her e-moderating method encourages continuous interaction and the appreciation of valuable group activity, and contains a special stage, namely socialisation.

It should be noted that the difficulties and critiques related to the different types of digital education and the suggested solutions are closely related to certain elements of socialisation. For example, interaction, metacommunication, active presence, role modelling, mutuality, responsibility, and community are essential for both general and professional socialisation (Cerrone, Citation2017; Serdyukov & Serdyukova, Citation2015; Weidman, Citation2006). The above-mentioned factors further underpin that it is worth thinking about digitalised learning and socialisation connectively provided that HE considers the training of intellectuals exhibiting critical, independent and civil attitudes its mission (Boulton & Lucas, Citation2011; Karpov, Citation2016).

Forms of digital teaching and learning necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic were not ideal versions of digital education from two viewpoints. Firstly, these forms were answers of HEI’s crisis management. Thanks to these, the digital shift took place within a few weeks (Márquez-Ramos, Citation2021) and this ensured continued education, although there was no time for precisely planned processes of this change. It was not possible to follow Selwyn’s (Citation2014) suggestion: namely all steps that lead to the expansion of digitalisation have to be considered and discussed. For CEE’s HEIs this change was especially challenging since many HEIs digitalised only their administrative processes related to e.g. finance and organisation (Komljenovic, Citation2020) up until the pandemic. Only a small proportion of teachers had reliable experience and expertise in connection with digital teaching.

Secondly, the pandemic blocked social life inside as well as outside universities. Thus, non-educational and ancillary functions based on personal meetings supporting digital education were cancelled. Accordingly, these circumstances created an extreme type of fully digitalised life and education without any in-person social contact beyond the realm of the family. The teaching staff of CEE’s HEIs, who were mostly cautious about and disinterested in (Jensen, Citation2019; Magyari, Citation2010; Ollé, Citation2010) the expansion of digitalisation – with a view to the above-mentioned dilemmas –, experienced this extreme form of digital teaching. The initially low level of digitalisation of HE and the digitalisation of almost all forms of social life led to the situation that the effect of COVID-19 and the effect of digitalisation cannot be fully separated in the CEE area.

To formulate the above very briefly, it was this interconnection and complexity between digitisation and socialisation that have caught our attention.

Methodology

This research is part of a 4-year-long research project titled “The future of business education”. One of the goals of this project is to identify the main trends affecting the future of HE in general, and business education in particular (Géring et al., Citation2020). In order to furnish a future-related research process with wide and macro-level scopes, horizon scanning has been chosen as the main research method to accomplish this task. However, future changes do not exist in a cultural vacuum as HEIs, their stakeholders and their expectations are culturally embedded (Géring et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, it must be borne in mind that we collected and analysed relevant materials through Central-Eastern European lenses, as mentioned before. This cultural context guided our notions about relevance and importance. For example, the problem of international student mobility was naturally among the issues under scrutiny, but from our perspective this topic has considerably less significance than for Anglosphere countries, where the percentage of international students is much higher in the student population. Additionally, based on the focus of our project, our business school oriented view meant that we mainly studied examples of HEIs with low educational infrastructure needs, such as HEIs in the fields of social sciences and economy, in contrast with special disciplines characterised by high educational infrastructure needs like medicine or physics.

In the first months of 2020, we started the horizon scanning project in the scope of which we focused on challenges and opportunities related to the future of HE. We identified three main themes in academic and semi-academic discourse, namely the transformation of knowledge transfer (Király & Géring, Citation2020); the challenges of flexible learning (Géring & Király, Citation2020); and changes in the certification of knowledge (Miskolczi & Tamássy, Citation2020).

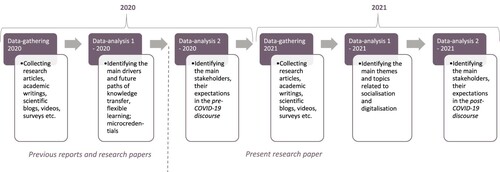

At this point, COVID-19 emerged, which – interestingly – belonged to one of the so-called wild card events in our collection of future-related phenomena. We were right in the middle of identifying the main stakeholders and their interests when the pandemic changed the whole educational landscape. Therefore, in 2021 we carried out a new data-collection with special attention to the effects of the pandemic (). Accordingly, in this “post-COVID-19” phase we focus on two topics: digitalisation, interpreted as an unavoidable phenomenon during these times, and socialisation, which got into the limelight due to the loss of face-to-face social relationships. This new scanning and data-analysis provide the main basis of this paper; however, in order to delineate the changes caused by COVID-19, we use the unpublished results of the stakeholder-identification process of the 2020 (pre-COVID-19) part of the project as well.

The reasons behind choosing horizon scanning as our main method are threefold. Firstly, horizon scanning (Géring et al., Citation2021) is a method which focuses on identifying and categorising relevant trends, topics, stakeholders, expectations, etc. related to a given phenomenon (here: HE). Secondly, horizon scanning is based on an especially wide-ranging collection of information and data (Könnöla et al., Citation2012) and is thus capable of accommodating unexpected themes, weak signals or even so-called wild card events, which have very low probability to occur, but if they do so, they exert tremendous effects (Saritas & Smith, Citation2011). Thirdly, horizon scanning is future-oriented, i.e. it allows for the formulation of future directions, paths or even scenarios, based on identified expectations, challenges and possibilities (Kuusi et al., Citation2015). This way we could contribute to enhancing the anticipatory competence not only of the experts and leaders of HE, but all of its stakeholders (Cuhls et al., Citation2015).

To realise the wide and open approach of horizon scanning, our data-collection processes both in 2020 and in 2021 focused on different types of sources (). On the one hand, we used typical academic sources. On the other hand, we collected information, ideas and perceptions from those type of semi-academic forums which are also built on expert knowledge, but are less formal and react much faster to changes than those texts which have to go through the time-consuming process of academic publishing. This latter aspect became even more urgent in the second phase of our research regarding the pandemic and its effect on HE ().

Table 1. Types and examples of collected materials.

The data-analysis of these materials was divided into two phases both in 2020 and in 2021. First, the researchers involved used a simple coding scheme to identify the main topics in the given materials as well as their effects and consequences on the future of HE. This phase of the analysis led to the identification of the main themes and topics in the academic and semi-academic discourse. The identified topics of our 2021 analysis are related to the interconnected themes of digitalisation and socialisation – the focus of our “post-COVID-19” analysis.

After scanning the thematic landscape, the second part of our data-analysis concentrated on the identification of the stakeholders and their interests in the given academic and semi-academic discourse. Here we should emphasise that this process focused on the collected sources and those stakeholders who appeared in these discourses. This way we were able to provide not only a list of the stakeholders mentioned, but we could also differentiate between those stakeholders whose voices, opinions and interests were “vocalised” most in the given discourse and those groups whose viewpoints were less markedly expressed. Accordingly, we were able to detect changes in the perceived importance and expectations of stakeholders with respect to the pre- and post-COVID-19 discourses as will be shown below.

Main themes, stakeholders and expectations after COVID-19

In what follows, our findings are presented. Firstly, an overview of the detailed phenomena map (Appendix 1–5) describing the central themes and main stakeholders are provided. Secondly, central topics and roles of stakeholders are analysed. Thirdly, from the perspectives of digitalisation and socialisation, it will be discussed how the pandemic affected main stakeholders and their demands. Finally, the comparison of changing and often contradictory expectations of important actors will be addressed in “pre- and post-COVID-19” discourses.

Overview of the map of identified phenomena

The phenomena map (Appendix 1–5) shows a high number of topics and stakeholders that emerged in our scan. It reveals the internal complexity of topics and the dense connections among them. HEIs are in the centre of the map surrounded by groups of topics relating to effects, interventions, reactions and expectations.

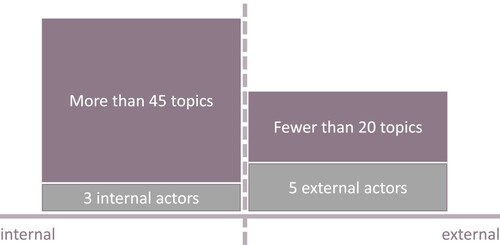

The most salient characteristic of the map is the difference between the number of themes associated with external and with internal elements related to HEIs (). Accordingly, below the details of the map are discussed along this internal-external axis.

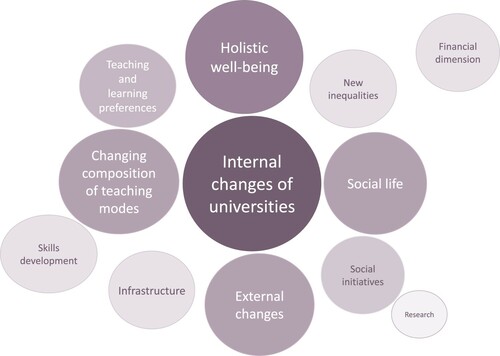

The main categories of the internal aspects (Appendix 1) are: internal changes of universities, holistic well-being, social life, changing composition of teaching modes, teaching and learning preferences, skills development, financial dimension, and new inequalities. Certainly, and not surprisingly, the main actors appearing in this post-COVID-19 discourse are the universities themselves as well as the students, and the teachers.

Furthermore, the external aspects featured a lot fewer elements (). Only one of the groups, the category of “external changes” merits attention thanks to its relatively higher number of elements. Others, such as direct social initiatives, infrastructure, research, and autonomy, were less emphatic in the discourses. These factors, however, can be associated with numerous external actors including the IT sector, funders, other education providers, employers, and the society.

The comparison of the two parts and, more specifically, the more emphatic internal aspect suggests that during the pandemic HEIs focused more extensively on their functioning and internal stakeholders. Even if less attention was paid to external stakeholders in these conversations, this does not mean that HEIs could not perceive changes in external factors or that they did not react to them, as it will be seen later.

After providing a first glance of the complexity and the proportion of issues and stakeholders, the interconnectedness thereof will be discussed below.

Composition of identified themes and the roles of actors

As a result of the pandemic, internal changes of universities seemed to become a central topic in the post-COVID-19 discourse (). Thanks to crisis management, the former slow-operating systems of HEIs reacted at a never-before-seen speed. For the maintenance of the HEIs’ operation, increasing internal cohesion, more extensive co-operation and resource re-allocation were needed. The related coping process highlighted the hidden potentials of the HEIs and the key role of management. Furthermore, non-educational tasks (e.g. volunteering or offering care for students and teachers) received more attention, and new elements emerged such as data policy relating to the spread of digitalisation.

The prominent role of holistic well-being in the post-COVID-19 academic and semi-academic discourse () emphasises HEIs’ function beyond the cognitive aspects of education. Accordingly, new teacher and student roles emerged, which will be detailed later. Furthermore, the newly introduced digital mode of education has highlighted that effective education requires more than the availability of learning materials, and has shown the importance of mental health, working conditions and financial security with respect to successful learning and teaching. The COVID-19 also brought to the fore holistic thinking about students and staff, and resulted in special support schemes.

Based on our scan, the changing composition of teaching modes necessitated by digitalisation seems to be an important and contradictory theme. The increased proportion of digital learning led to a more realistic knowledge about the values and weaknesses of different teaching modes. At the same time, with the wider use of the digital mode, questions relating to learning efficiency and exam cheating emerged.

Additionally, the lack of social life was understandably the main problem most stakeholders struggled with. They experienced not only the absence of campus life and social interactions, but the lack of international exchanges, and consequently a lack of networking and building social capital as well.

Even though new inequalities and research activities can be found among the less prominent themes, they do deserve attention. From the perspective of inequalities, the post-COVID-19 academic and semi-academic discourse revealed that digitalisation is connected to individuals’ socio-economic backgrounds and created new differences with respect to access to high-speed Internet connection, devices, and the level of digital literacy. Regarding research, in contrast to other functions of HEIs, research has been pushed into the background, with the exception of COVID-oriented research activities.

The above-mentioned topics are reflected in the interrelations between themes and actors. Concerning the scanned sources, shows those actors that have a minimum of fivefold mention together with certain themes.

Table 2. Relations between topics and actors (connections appearing at least 5 times in the scanned discourse are shown).

As previous results clearly indicate and as it is also shown here by the darker rows (), the perspectives of universities as institutions as well as the viewpoints of students and teachers are emphatically articulated in the post-COVID-19 discourse with respect to almost every topic.

Even if external actors appeared less frequently in connection with the scanned topics, they cannot be neglected, either. In the post-COVID-19 discourse society as a concerned stakeholder appeared in half of the subjects discussed. Contrarily, the perspectives of IT and – especially – those of employers and funders rarely appeared. Even so, there are some topics where their roles and influence were addressed. An interesting aspect is the involvement of the IT sector in social initiatives and typically non-digital tasks.

After examining the roles of stakeholders in the scanned sources, the positive and negative effects of the pandemic on key stakeholders will be analysed in terms of digitalisation and socialisation.

Effects of the pandemic on main stakeholders and their expectations concerning digitalisation and socialisation as discussed in the sources

The pandemic led to an era of increasing unpredictability, worries about the future, and extended digitalisation. Obligatory measures to stop the spread of the coronavirus on and beyond campuses and changes in the operation of HEIs had different impacts on the main stakeholders from the viewpoint of digitalisation and socialisation. As mentioned earlier, the CEE region had very little preliminary experience with digital education. Therefore, using a little exaggeration, we could say that the full digitalisation caused by the pandemic provided the very first experience of digital education. As a result, different stakeholders experienced positive and negative effects, and formulated new demands based on them.

Firstly, impacts related to students and teachers are introduced in a comprehensive table. The reason for doing so is that, in connection with these two stakeholders, very similar topics appeared in the discourse about the effects of the pandemic. ()

Table 3. Positive and negative impacts on students and teachers.

As mentioned earlier, the pandemic made it possible that almost all students and teachers had the chance to get real experience in digital education. Both could seize the opportunity to develop their skills and learn new teaching and learning techniques or, alternatively, encountered the limits of their competencies and IT equipment. The analysed materials showed that these experiences divided the internal stakeholder groups into two. One part of the students and teachers wanted to get back their campus life (Losh, Citation2021), but the other part preferred to remain in the digital mode (Zimmerman, Citation2020). It is also clear from the discourse that face-to-face teaching methods are still popular. For instance, a research project mainly based on samples from Croatia, Romania and Czechia showed that the lack of personal teacher-student interaction increased the risk of negative study experience (Barada et al., Citation2020). Even so, there exists an almost unanimous opinion that some of these methods will be – at least partly – replaced by online solutions (like online videos instead of crowded lectures). After scanning the discourse, it became obvious that the acceptance of the digital mode increased in the CEE countries as well. However, it also became evident that teachers and students still require technical support and skills development from the university so that they are able to manage their working or learning processes in the digital environment. In connection with this, a survey showed that the level of digital competencies of the young (aged 16-24) in some CEE countries like Hungary was lower than that of the EU average (Tomaževič et al., Citation2021).

Unfortunately, the digital mode of education and social separation caused several health problems (Rizun & Strzelecki, Citation2020). Although the total closure due to the pandemic in itself led to difficulties, it is extensively discussed that such problems could also be the result of having to endure long periods of digital presence (Williamson et al., Citation2020b) as for instance: the growing risk of Internet addiction, anxiety or depression. Since students and teachers had to work and learn from home, it was harder to separate work and private life, which upset the balance between work-life and learn-life (IAU, Citation2020). This sometimes produced even more increased burdens on teachers: for example, they often had to teach their students and their own children in parallel. Furthermore, teachers, who typically have the closest contacts with the students, had to develop new roles and become tutors, learning material developers and psychologists as well. Therefore, the risk of staff burnout also increased (IAU, Citation2020). These factors led to new expectations toward the university and the IT sector and necessitated mental health and holistic well-being support services to students and teachers.

Another problematic aspect of digitalisation is in close connection with less controlled digital knowledge assessment. In order to accomplish course requirements new forms of exam cheating emerged (Daumiller et al., Citation2021; IAU, Citation2020). As a consequence, students and teachers formulated that universities should solve ethical issues of online exams and tests.

As for the socialisation aspect of the COVID-19 restrictions and widening digitalisation, maybe the greatest challenge for both actors was the lack of personal contacts. The analysed materials emphasise that the absence of face-to face interactions and joint activities is observable in connection with, among others, mental health issues, difficulties in establishing relationships and social capital, lack of international exchange and intercultural immersion opportunities, as well as freshmen’s integration. According to a Polish study, students missed campus life itself to a lesser extent than joint social activities with their peers in restaurants, bars and cinemas (Szczepańska & Pietrzyka, Citation2021).

Additionally, in the scanned material, examples of some positive consequences can be identified: collaboration among students and teachers increased in order to provide support to one another (Hunter & Sparnon, Citation2020). Furthermore, bottom-up volunteering programmes were able to replace, to some extent, joint activities of students and teachers. In general, both students and teachers wanted to take part in university social life and – in the absence of a better alternative – requested online solutions.

Concerning negative effects, the lack of personal contacts and informal information exchanges resulted in internal stakeholders’ increased demand for more frequent and clear communication with their institutions, as proven by the analysed discourse (e.g. QS, Citation2020). This is especially important for freshmen because this student group previously did not have enough information related to university life and could not establish their own support network, thus fitting into the university community might have been problematic for them. They also expected support from the university and student organisations for being involved and guided in university life. As attested by the discourse, students require some kind of online social skills development as well as international, cultural and external experience from the university.

Apart from teachers and students, HEIs themselves also faced several issues and challenges as organisations ().

Table 4. Positive and negative effects on institutions.

In order to continue education, universities were forced to accomplish a digital shift. As a result, both positive and negative effects occurred at an organisational level (). Although digitalisation led to – somewhat forced – infrastructure development, we should be aware of financial issues and autonomy related questions prompted by related development processes. Even though a Romanian survey highlighted how difficult the adaptation of digital tools proved to be in some CEE countries – especially in the case of smaller universities (Edelhauser & Lupu-Dima, Citation2020) –, such adaptation could lead to increasing flexibility of teaching processes through these digital solutions. In turn however, HEIs should be aware of regulatory and ethical issues, especially in connection with online exams and evaluation.

Beyond infrastructural and education developments, HEIs discovered and could count on the hidden potential of their teaching staff, who improved their skills and mindset while they were also learning and teaching. According to our collected materials, the staff showed extreme flexibility and adaptability. Moreover, the staff was able to innovate solutions to increase students’ online study experience. At a Czech University, a library offered exceptional full online access to all its books (czechuniversities.com, Citation2020). Another example is a collaboration between the University of Szeged (Hungary) and Coursera, which provides an online education platform for “learning how to learn” (Tomaževič et al., Citation2021).

However, besides these positive effects, negative ones also appeared in connection with the role of university buildings and with ensuring safe environments for teaching and learning (). Most dormitories and buildings were closed. In the meantime, however, accommodation had to be provided for some. HEIs had to create conditions that prevented the virus from spreading, and financial issues also arose in connection with the maintenance of nearly empty buildings.

It is important to mention some positive and negative effects of COVID-19 related to the society and the IT sector. As part of a legitimacy debate and a worldwide crisis, one of the less prominent but most important effects on society was that HEIs showed their direct usefulness through e.g. research and volunteering. For example, in Hungary there are universities which started to develop equipment for hospitals (Óbuda University, Citation2020), and a Czech university produced disinfectants (czechuniversities.com, Citation2020). Also, there were negative impacts that include new inequalities, declining social relationships, and students’ growing mental health problems, which were perceived by a wider part of the society. Therefore, HEIs were expected to identify persons and groups in danger and offer holistic support.

To move on to another important player in the HE sector, we can see that the unanimous winner of the pandemic was the IT sector. This is not surprising because people required more digital tools and equipment for their work and private lives as well. The educational market opened up for the IT sector and for them this situation meant new investment opportunities (Williamson et al., Citation2020b).

This section argued that altered circumstances and answers by HEIs generated new expectations. As these summarised results clearly indicate universities have to handle manifold and contradictory expectations. Below, we will focus on these expectations in comparison with the pre-COVID-19 discourse.

Stakeholders’ expectations before and after COVID-19

As introduced in the methodology section, our data collection is not restricted to the post-COVID-19 discourse, but also include a comprehensive search executed just before the pandemic. In the following, we will focus on the changes in stakeholders’ expectations, and on changes in the “strength of their voices” as attested by the analysed materials. The expectations based on the scanned discourse before and after the COVID-19 pandemic are summarised in .

Table 5. Changes of expectations based on scanned materials.

As can be seen in , the voice of some actors changed in the scanned discourse. Institutions’ growing internal focus is mirrored by more frequent conversations and more diverse topics in relation with internal actors. Expectations of students and teachers are still central and can easily be defined because their perspectives are widely presented in both discourses. Thanks to the pandemic, their demands became more similar and eventually overlapped, which made their expectations more prominent. Society seems to be an important actor both before and after COVID-19. Before the pandemic, however, a lot of different social groups had controversial demands related to HE. The pandemic forged society into a more cohesive group in terms of expectations, or at least this is the way it appears in the post-COVID-19 discourse. Naturally, even if universities are important actors of HE, in the pre-COVID-19 discourse they appeared as an institutional background of stakeholders’ activity. At the same time, in the post-COVID-19 discourse they were one of those active actors whose involvement and responsibilities were discussed extensively. The IT sector has a special position among other actors: the demands it put forward almost disappeared from the discussions in spite of its determinative role during the pandemic, and most of its former expectations were met. In fact, employers, funders and other educators in general acting as “demand formulators” received less attention in the post-COVID-19 discourse.

The diversity and contradiction between the expectations of the actors can be traced in the analysis of the pre-COVID-19 situation. For example, there appeared a clearly-delineated student group that only demanded profession-specific, practical, immediately applicable knowledge. As opposed to this, another student group expected a wide range of knowledge in order to widen their horizons. In contrast, at the time of the COVID-19, requirements became more focused on recent problems and possible solutions to such problems at personal, institutional, and global levels. Naturally, this does not mean that contradictions totally vanished. For example, one part of the students and teachers want to continue in the digital mode and the other part wants face-to-face education. Furthermore, universities need to realise infrastructure developments, but funders prefer cost-effective operations. Therefore, it still presents a well-known task for universities to balance expectations.

As a result of recent difficulties, new expectations emerged and were placed in the limelight including holistic well-being, communication, new inequalities and the tasks of HE related to these. On the other hand, the focus of some demands shifted. For example, instead of the unquestionable expansion of digitalisation in every part of HE, which was a general theme in the pre-COVID-19 discourse, after the pandemic the discourse was much more clearly about the social opportunities and socialisation aspects of the digital mode. In the case of students, the demands articulated in the scanned materials show an explicit change. The emphasis has clearly shifted from compliance to employers, to well-being and maintaining social relationships with peers and teachers. Furthermore, students and teachers expect HE and the IT sector to produce solutions to promote general and professional socialisation, as shown in the analysed materials (e.g. collected university surveys).

All in all, due to the pandemic, the so far mainly technology-oriented and digital-based view of the future of HE turned into a complex, human, social and interaction focused approach. Currently, it cannot be predicted which expectations will continue to exist after the pandemic, but it is clear that COVID-19 has brought important aspects and voices into the discourse about the future of HE.

Discussion

Based on our horizon scan of the main stakeholders and their expectations in the pre- and post-COVID-19 academic and semi-academic discourse, below we will discuss reasons, consequences and dilemmas concerning the changes in actors’ voices and demands to be followed by a discussion on the interconnected feature of digitalisation and socialisation. Finally, based on our results, we will assess whether what we saw in HE before and during the pandemic was “simply” crisis management, or constitutes the first steps to the future of HE.

Reasons, consequences and dilemmas

According to the scanned materials, HEIs appeared to pay more attention to external requirements before the pandemic. However, as a result of the pandemic, the attention of HEIs moved from external to internal actors. The reason for this shift could be increased direct responsibility for internal stakeholders as well as the fact that students, teachers and the university itself had key roles in maintaining education in an online environment. At the same time, this shift from external to internal approaches can be observed in connection with other stakeholders, too. For example, in the pre-COVID-19 discourse, students focused on satisfying various demands of external actors, especially employers. Students’ worries about their future careers dominated the discourse about the future of HE. In turn, today students’ holistic well-being and socialisation are discussed as these are similarly important and pressing issues. Additionally, it can be assumed that external stakeholders also focused on themselves during the pandemic. The reason for this could be the necessity of crisis management in order to survive and increased internal responsibility. As a consequence, external stakeholders did not have the capacity to formulate any kind of expectations towards HE.

A temporary lift of the pressure from external actors’ expectations and increasing internal focus led to the recognition of HEIs’ potentials and issues, which situation encouraged institutions to think of their future operations, functions and priorities from such emerging perspectives. On the one hand, hidden internal resources came to the surface and potential partners to cooperate with and to offer joint or shared courses with emerged. The advantages of participation in university associations were highlighted. In addition, lessons learned from the pandemic can be incorporated into learning materials.

Additionally, some questions require decisions from HEIs in the future. Accordingly, universities have to choose their strategy in connection with university buildings (to keep them as they were before the pandemic, to redesign or to sell them). Furthermore, HEIs have to examine opportunities of collaboration with other actors (e.g. other education providers, employers, the IT sector) in providing quality online education. Each university should consider the risks and opportunities of these partnerships and, alternatively, should also assess their institutional autonomy. Also, handling new forms of exam cheating can, in the long run, weaken the value of students’ efforts and will devalue their degrees; these issues also require institutions’ attention and regulation in order to maintain trust in the quality of education.

Interaction between socialisation and digitalisation

The examination of the interaction between digitalisation and socialisation can be based on real experiences with digital education during the pandemic. However, we have to be aware that the digital education experienced was special in two aspects. Firstly, it was not a carefully planned and gradually introduced transformation but an abrupt switch between teaching modes. Secondly, fully digital education went hand in hand with total closure, thus, social(isation) opportunities became and were extremely limited, and/or restricted to online spaces only. Accordingly, we have to be careful in making conclusions about the effects of the pandemic and fully digitalised education because they were intertwined. At the same time, however extreme this situation was, it shed light on such important aspects of digital education that are closely connected to socialisation. This should also be closely considered in relation to the future of HE.

As for the significance of digitalisation, it is clear that the much-needed more extensive use of digitalisation in HE could be realised within a few weeks in CEE countries, too. Even if the introduction of this version of online education was not planned and was full of mistakes, it still guaranteed the opportunity for thousands of students to continue their studies and also enabled teachers to keep their jobs during the pandemic. Furthermore, the widespread use of digital methods and tools broke the ice, thus decreasing resistance of the CEE’s HE to digitalisation. Therefore, many viewpoints came to the surface paving the way for further considerations. Thanks to this, stakeholders had to face the realisation that the digital mode does not suit everyone. The success or failure of the digital mode brought into the limelight, among others, the importance of learning styles, the level of autonomous learning and motivation, and students’ coping strategies. These, in turn, outlined some of those elements that should be considered when HEIs plan and make decisions about, for instance, their portfolio, and mix of teaching modes.

Also, in addition to digital education, other digital opportunities were tested during this period. As mentioned earlier, in the lack of other options, HEIs and their stakeholders sought to sustain and partially replace university social life and events by online solutions. General lockdowns resulted in a situation that participation in social activities outside universities became impossible, therefore classes and online events served as links for internal stakeholders to the outside world. The interpretation of digital education in CEE, and thoughts about its future are closely intertwined with the full closure experience. This could be one of the reasons behind the increased focus on the socialisation aspect of digital education in the analysed post-COVID-19 discourse.

Nonetheless, we should be aware that although these online social activities were essential, mental health issues emerging during this period highlighted that such online events could not fully replace the social experience of being together and engaging in joint activities. Stakeholders had to make do without, among others, accidental conversations in the corridor or while waiting for teachers, spontaneous interactions, physical contact, metacommunication, observing teachers and professionals during work and students in upper years, or the emotionally stimulating effects of such activities which constitute important parts of socialisation (Saigushev et al., Citation2020; Van Maanen & Schein, Citation1979; Wong & Chiu, Citation2019). In lack of student involvement, this way an important step in socialisation was missed (Weidman, Citation2006), and less time remained for the process. The results of this lack of socialisation will be seen only later when students begin their careers and post-HE lives. For this purpose, further research is essential, because the so-far accumulated experiences partly reinforce some of the former worries about the expansion of digitalisation (Krishnamurthy, Citation2020).

If there are some initiatives regarding the improvement of online classrooms’ social activities (Castellanos-Reyes, Citation2020; Salmon, Citation2007; Serdyukov & Serdyukova, Citation2015), teachers in CEE should discover and incorporate them. Furthermore, teachers could face that etiquette and expected behavioural norms of online classrooms facilitate the acquisition of general social norms, too. Moreover, finding solutions to proliferating ethical issues like cheating, plagiarism, and their regulation would be an important element of formal institutional socialisation.

Continuing the theme of socialisation, HEIs can serve as models e.g. through using science-based communication, through their support of society with their intellectual, material and human resources, and through their cooperation with others. Thanks to these actions or the lack thereof, on the one hand, HEIs could have a socialising effect. On the other hand, the position of HEIs could strengthen or weaken at the local or sector level as well. In addition, the capabilities of the teachers to realise a digital shift and their supportive, flexible attitude during the pandemic can also serve as models.

All in all, the commonly shared experience of the pandemic undoubtedly provided a much more nuanced view about digitalisation, which was previously often described either as the way to a bright and modern future or as a tool which will result in alienated persons sitting all day long at computers. We argue that the complexity of the issues discussed in the analysed discourses indicate that in the post-COVID era digitalisation and socialisation will be perceived as interconnected and equally important aspects of the future of HE rather than two independent phenomena of education (as opposed to the pre-COVID-19 discourse, which was a general characteristic then). This may further reinforce universities’ roles beyond the cognitive development of students, and may influence institutions e.g. in selecting their strategies in relation to buildings or their decisions concerning resource allocation or the outsourcing of certain tasks.

Crisis management and/or the first steps to the future?

It is clear that not only the HE sector but the whole world is in a special situation as a consequence of COVID-19. For that reason, we must be very careful when examining the different effects and changes brought about by the pandemic. This is clearly a crisis, therefore most of the changes and reactions were acts of crisis management, and did not constitute a well-prepared, completely deliberate and strategic series of actions. However, this situation caused the emergence of potential hidden elements in the system and changed not only the circumstances but also the main values and stakeholders’ expectations. The most interesting and important question is what will happen after the pandemic is over. Will HEIs return to their earlier structure and operation, or will they be able to incorporate some of the opportunities and positive changes that emerged during the pandemic?

As our results also show, the system of stakeholders’ requirements is very complex, and it is undergoing considerable transformation due to the pandemic. Accordingly, in order to move forward, HEIs have to scrutinise these altered expectations and should try to find a new balance between their missions and their internal and external responsibilities. One of the lessons of the pandemic is that more flexible systems are needed which are able to more easily respond to local demands and global challenges.

In sum, in our opinion, the future of HEIs can only be built on the mapping of their ecosystems and on the expectations of their local stakeholders. This approach could support the construction of different future scenarios and consequently aid decisions about the future of HE.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to investigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on important actors and their expectations concerning the HE sector, with special emphasis on digitalisation and socialisation in HE. As open organisations HEIs are influenced and formed by numerous and often contradictory expectations of external and internal stakeholders. The balance between key actors and their different needs has a determinative role concerning the path HEIs are going to take in the future. That also underpins the reason why the future-oriented horizon scanning method was used for mapping the emphatic demands of actors and also for comparing such demands before and after the pandemic.

The more extensive use of digitalisation was one of the most important trends even before the pandemic in the CEE countries. Compared to digitalisation, socialisation related expectations were less marked but not less important in the pre-COVID-19 discourse. In contrast, due to the closures during the pandemic, not only learning, but almost all forms of social life inside and outside the university could be realised only online. The awaited digitalisation in HE was realised within a few weeks, although an extreme form of digital education completely free of face-to-face encounters was introduced. Not only students but also teachers and society in general became interested in finding new solutions in university social life. As attested by the post-COVID-19 scan, all of these circumstances have drawn attention and amplified the need for social relationships, interaction, and socialisation itself. Moreover, this demand for social elements can be a central factor in further developing digital learning environments.

With a view to the interconnectedness of digitalisation and socialisation, this paper showed some of both the negative and positive effects of the pandemic from the perspectives of HE’s main stakeholders. It has been shown that changing requirements and newly appearing, but so far hidden, opportunities can strengthen universities. Inevitably, the nature of the crisis has to be seen, therefore it is not clear yet what will happen until a new balance is formed after the pandemic. This article highlighted some aspects related to the interconnected feature of digitalisation and socialisation worthy of consideration when HEIs choose their future paths in the post-COVID-19 era.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use the wide interpretation of Central-Eastern Europe. Basically, the European post-communist countries are included in CEE e.g. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bulgaria.

References

- Altbach, P., & de Wit, H. (2020). Postpandemic outlook for higher education is bleakest for the poorest. International Higher Education, 102, 3–5. https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/view/14583

- Barada, V., Doolan, K., Burić, I., Krolo, K., & Tonković, Z. (2020). Student life during the Covid-19 pandemic: Europe-wide insights. Ministry of Science and Education and its National Committee for Social Dimension in Higher Education. http://www.ehea.info/Upload/BFUG_HR_UA_71_8_1_Survey_results.pdf

- Bejinaru, R. (2013). Impact of digitalization on education in the knowledge economy. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 7(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25019/MDKE/7.3.06

- Boulton, G., & Lucas, C. (2011). What are universities for? Chinese Science Bulletin, 56(23), 2506–2517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-011-4608-7

- Brennan, J., & Teichler, U. (2008). The future of higher education and of higher education research. Higher Education, 56(3), 259–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9124-6

- Carlsen, R. (2003). Building productive online learning communities invetigating and interacting with internet educational genres. In G. Davies & E. Stacey (Eds.), Quality education @ a distance. IFIP — The International Federation for Information Processing (Vol. 131, pp. 137–144). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-35700-3_15

- Castellanos-Reyes, D. (2020). 20 years of the Community of Inquiry Framework. TechTrends, 64(4), 557–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00491-7

- Cerrone, E. R. (2017). Socialization of undergraduate rural students in a large urban university [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Pittsburgh.

- Cuban, L. (1993). Computer meets classroom: Classroom wins. Teachers College Record, 95(2), 185–210.

- Cuhls, K., Erdmann, L., Warnke, P., Toivanen, H., Toivanen, M., van der Giessen, A. M., & Seiffert, L. (2015). Models of horizon scanning. In How to integrate horizon scanning into European research and innovation policies (pp. 1–55). European Commission. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1938.7766

- Czech Universities. (2020, April 4). The Czech Technical University turned into a scientific manufactory. https://www.czechuniversities.com/article/faculties-at-the-czech-technical-university-turned-into-a-scientific-manufactory

- Daumiller, M., Rinas, R., Hein, J., Janke, S., Dickhäuser, O., & Dresel, M. (2021). Shifting from face-to-face to online teaching during COVID-19: The role of university faculty achievement goals for attitudes towards this sudden change, and their relevance for burnout/engagement and student evaluations of teaching quality. Computers in Human Behavior, 118, 106677. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106677

- Edelhauser, E., & Lupu-Dima, L. (2020). Is Romania prepared for eLearning during the COVID-19 pandemic? Sustainability, 12(13), 5438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135438

- Facer, K. (2018). The university as engine for anticipation: Stewardship, modelling, experimentation and critique in public. In R. Poli (Ed.), Handbook of anticipation: Theoretical and applied aspects of the use of future in decision making (pp. 1–18). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31737-3_29-1

- Fűzi, B. (2019). Should we and can we motivate university students? – The analysis of the interpretation of the role and the teaching methods of university teachers. In K. Cermakova & J. Rotschedl (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th teaching & education conference, London. International Institute of Social and Economic sciences (IISES) (pp. 36–57). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20472/TEC.2019.007.004

- Géring, Z., & Király, G. (2020). Changes in teaching and learning – The challenges of flexible learning. Horizon Scanning Report Series, Volume II. Future of Higher Education Research Centre, Budapest Business School.

- Géring, Z., Király, G., & Tamássy, R. (2021). Are you a newcomer to horizon scanning? A few decision points and methodological reflections on the process. Futures & Foresight Science, 3(3-4), e77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ffo2.77

- Géring, Z., Király, G., Tamássy, R., Miskolczi, P., Fűzi, B., & Pál, E. (2020). Decline or renewal of higher education. Threats and possibilities amidst a global epidemic situation. Horizon Scanning Report Series. Future of Higher Education Research Centre, Budapest Business School.

- Gumport, P. J. (2000). Academic restructuring: Organizational change and institutional imperatives. Higher Education, 39(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003859026301

- Gupta, S. B., & Gupta, M. (2020). Technology and E-learning in higher education. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(4), 1320–1325.

- Hunter, F., & Sparnon, N. (2020). There is opportunity in crisis: Will Italian universities seize it? [Special issue]. International Higher Education, 102, 38–39. https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/view/14625

- IAU. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world. IAU Global Survey Report. https://www.iau-aiu.net/IAU-Global-Survey-on-the-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Higher-Education-around-the

- Irwin, C., & Berge, Z. (2006). Socialization in the online classroom. e-Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 9(1). https://mdsoar.org/handle/11603/16246

- Jensen, T. (2019). Higher education in the digital era. The current state of transformation around the world. International Association of Universities (IAU).

- Jongbloed, B., Enders, J., & Salerno, C. (2008). Higher education and its communities: Interconnections, interdependencies and a research agenda. Higher Education, 56(3), 303–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9128-2

- Kaplan, A. (2020). Covid-19: A (potential) chance for the digitalization of higher education. ESCP Impact Paper No. 2020-72-EN. ESCP Research Institute of Management (ERIM).

- Karpov, A. O. (2016). Socialization for the knowledge society. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(10), 3487–3496.

- Király, G., & Géring, Z. (2020). Changes in teaching and learning – The transformation of knowledge transfer. Horizon Scanning Report Series, Volume I. Future of Higher Education Research Centre, Budapest Business School.

- Komljenovic, J. (2022). The future of value in digitalised higher education: Why data privacy should not be our biggest concern. Higher Education, 83(1), 119–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00639-7

- Könnöla, T., Salo, A., Cagnin, C., Carabias, V., & Vilkkumaa, E. (2012). Facing the future: Scanning, synthesizing and sense-making in horizon scanning. Science and Public Policy, 39(2), 222–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs021

- Kosslyn, S. M., Nelson, B., & Kerrey, B. (2017). Building the Intentional University: Minerva and the future of higher education. MIT Press.

- Krishnamurthy, S. (2020). The future of business education: A commentary in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research, 117, 1–5, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.034

- Kuusi, O., Cuhls, K., & Steinmüller, K. (2015). The futures map and its quality criteria. European Journal of Futures Research, 3(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-015-0074-9

- Lee, R. M., & Yuan, Y. (2018). Innovation education in China: Preparing attitudes, approaches, and intellectual environments for life in the automation economy. In N. W. Gleason (Ed.), Higher education in the era of the fourth industrial revolution (pp. 93–119). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-981-13-0194-0_5

- Losh, E. (2021, Feruary 4). Universities must stop presuming that all students are tech-savvy. Times Higher Education, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/universities-must-stop-presuming-all-students-are-tech-savvy

- Maassen, P. (2000). Higher education and the stakeholder society. Editorial. European Journal of Education, 35(4), 377–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-3435.00034

- Maassen, P. (2014). A new social contract for higher education? In G. Goastellec & F. Picard (Eds.), Higher education in societies (pp. 33–50). Sense Publishers.

- Magyari, B. I. (2010). A kreativitás fejlesztése a felsőoktatásban [Developing creativity in higher education]. In I. Dobó, I. Perjés, & J. Temesi (Eds.), Korszerű felsőoktatási pedagógiai módszerek, törekvések [Modern higher education pedagogical methods and aspirations] (pp. 49–63). Corvinus University of Budapest.

- Mainardes, E. W., Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2010). An exploratory research on the stakeholders of a university. Journal of Management and Strategy, 1(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5430/jms.v1n1p76

- Marathe, D. S. (2018). Digitalization in education sector. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, [Special Issue-ICDEBI2018], 51–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31142/ijtsrd18670

- Márquez-Ramos, L. (2021). Does digitalization in higher education help to bridge the gap between academia and industry? An application to COVID-19. Industry and Higher Education, 35(6), 630–637. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422221989190

- Miskolczi, P., & Tamássy, R. (2020). Changes in the certification of knowledge. Horizon Scanning Report Series, Volume III. Future of Higher Education Research Centre, Budapest Business School.

- Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/259247

- Ollé, J. (2010). Egy módszer alkonya: a katedrapedagógia végnapjai a felsőoktatásban [Twilight of a method: The final days of cathedral pedagogy in higher education]. In I. Dobó, I. Perjés, & J. Temesi (Eds.), Korszerű felsőoktatási pedagógiai módszerek, törekvések [Modern higher education pedagogical methods and aspirations] (pp. 22–31). Corvinus University of Budapest.

- Óbuda University. (2020, April, 4). Mass ventilator system – The Hungarian Invention Could Save Lives. http://news.uni-obuda.hu/en/articles/2020/08/07/mass-ventilator-system-the-hungarian-invention-could-save-lives

- Peters, M. A., Rizvi, F., McCulloch, G., Gibbs, P., Gorur, R., Hong, M., Hwang, Y., Zipin, L., Brennan, M., Robertson, S., Quay, J., Malbon, J., Taglietti, D., Barnett, R., Chengbing, W., McLaren, P., Apple, R., Papastephanou, M., Burbules, N., … Misiaszek, L. (2020). Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-COVID-19. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655

- QS. (2020). The impact of the Coronavirus on global higher education. Quacquarelli Symonds. https://www.qs.com/contact/

- Raich, M., Dolan, S., Rowinski, P., Cisullo, C., Abraham, C., & Klimek, J. (2019). Rethinking future higher education. European Business Review. https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/rethinking-future-higher-education/

- Rizun, M., & Strzelecki, A. (2020). Students’ acceptance of the COVID-19 impact on shifting higher education to distance learning in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186468

- Rumyantseva, I. A., Krotenko, T. Y., & Zhernakova, M. B. (2020). Problems of digitalization: Using information technology in business, science and education. Scientific and Technical Revolution: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 129, 561–570. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47945-9_61

- Saad-Filho, A. (2020). From COVID-19 to the end of neoliberalism. Critical Sociology, 46(4-5), 477–485. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520929966

- Saigushev, N. Y., Vedeneeva, O. A., & Melekhova, Y. B. (2020). Socialization of students’ personality in the process of polytechnic education. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Far East Con” (ISCFEC 2020), 128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.200312.194

- Salmon, G. (2007). 80:20 for E-moderators. CMS-Journal, 29, 39–43. http://edoc.hu-berlin.de/cmsj/29/salmon-gilly-39/PDF/salmon.pdf

- Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating. The key to online teaching and learning. Routledge.

- Saritas, O., & Smith, J. E. (2011). The big picture – Trends, drivers, wild cards, discontinuities and weak signals. Futures, 43(3), 292–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.11.007

- Scott, W. R. (2003). Organizations and organizing: Rational, natural, and open system perspectives. Prentice-Hall.

- Selwyn, N. (2014). The internet and education. In Change: 19 key essays on how the internet is changing our lives (pp. 191–216). OpenMind.

- Selwyn, N. (2021). “There is a danger we get too robotic”: An investigation of institutional data logics within secondary schools. Educational Review. Advance online publication. 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1931039

- Selwyn, N., Hillman, T., Eynon, R., Ferreira, G., Knox, J., Macgilchrist, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2020). What’s next for Ed-tech? Critical hopes and concerns for the 2020s. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1694945

- Serdyukov, P., & Serdyukova, N. (2015). Effects of communication, socialization and collaboration on online learning [Special issue]. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 11(10).

- Shin, N. (2003). Transactional presence as a critical predictor of success in distance learning. Distance Education, 24(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910303048

- Sneyers, E., & De Witte, K. (2018). Interventions in higher education and their effect on student success: A meta-analysis. Educational Review, 70(2), 208–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1300874

- Szczepańska, A., & Pietrzyka, K. (2021). The COVID-19 epidemic in Poland and its influence on the quality of life of university students (young adults) in the context of restricted access to public spaces. Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01456-z

- Tomaževič, N., Ravšelj, D., & Aristovnik, A. (2021). Higher education policies for developing digital skills to respond to the Covid-19 Crisis: European and global perspectives. European Liberal Forum.

- Van Maanen, J., & Schein, E. H. (1979). Toward a theory of organizational socialization. Research in Organizational Behavior, 1, 209–264.

- Weidman, J. C. (2006). Socialization of students in higher education: Organizational perspectives. In C. C. Conrad & R. C. Serlin (Eds.), The Sage handbook for research in education: Engaging ideas and enriching inquiry (pp. 253–262). Sage Publications.

- Williamson, B., Bayne, S., & Shay, S. (2020a). The datafication of teaching in higher education: Critical issues and perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1748811

- Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020b). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641

- Wolff, J. (2013). It’s too early to write off the lecture. Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2013/jun/24/university-lecturestill-best-learning.

- Wong, B., & Chiu, Y. T. (2019). Let me entertain you: The ambivalent role of university lecturers as educators and performers. Educational Review, 71(2), 218–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1363718

- Zawacki-Richter, O. (2021). The current state and impact of COVID-19 on digital higher education in Germany. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 218–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.238

- Zimmerman, J. (2020, March 10). Coronavirus and the great online-learning experiment. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/coronavirus-and-the-great-online-learning-experiment/

Appendices

Appendix 1. Phenomena map

Appendix 2. Division of the phenomena map

Appendix 3. 1st part of internal elements of the phenomena map

Appendix 4. 2nd part of internal elements of the phenomena map

Appendix 5. 3rd part of internal elements of the phenomena map

Appendix 6. External elements of the phenomena map