ABSTRACT

According to the Swedish Education Act, schools should support both students’ knowledge development and personal development. Students’ levels of knowledge are measured and compared through their examination results and formal grades as well as through international comparative studies and other tools. However, students’ personal development is not measured. The purpose of this study is to explore the efforts of local governance chain actors – the Local Educational Authority (LEA), superintendents, principals and teachers – to realise these two normative requirements and to learn more about the tensions and power struggles between these actors. The overarching question is: How do the actors in the governance chain prioritise and act with regard to the requirements for developing students’ knowledge and students as individuals? This study is designed as a case study in a compulsory school setting. The empirical data were collected by interviewing LEA chairs, superintendents, principals and teachers in a small town in the south of Sweden. The results show that the LEA and the superintendents focus on students’ knowledge development, but principals and teachers resist a too strong focus on knowledge development. The normative requirement – students’ personal development – is not explicitly discussed at any level in the governance chain.

Children’s rights are part of human rights (Hart et al., Citation2001; Hart & Pavlovic, Citation1991; Quennerstedt, Citation2013). A basis for defining children’s rights is the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, Citation1989). In Article 28 of the Convention, the States Parties declare that they recognise the right to education. Accordingly, educational arrangements must be understood in an international context and cannot be regarded as a solely national matter (Quennerstedt, Citation2010). Thus, norms in nations’ statutes are influenced both by national values and by international conventions. In 2018, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child became Swedish law.

At the national level, statutes define the overall aims that the nation’s school system must achieve. In Sweden, the overall aim – the normative order – for the school system is explicitly formulated in the Education Act (SFS, Citation2010:800). The Act stipulates that students should develop their knowledge and values, while education should promote students’ development and learning as well as instil in them a lifelong desire to learn (Ch. 1 § 4). In accordance with these norms, education has two main goals: (i) to develop a student’s knowledge and (ii) to develop the student as a person. The extent to which a school succeeds in fulfilling the first normative order (developing knowledge) is measured and reported by means of its students’ grades.

Although it may be difficult to compare different countries’ legal school regulations, it can be noted that the discussion of students’ personal development is not an exclusive Swedish phenomenon. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, Citation2021) states that:

Success in education today builds not just cognitive but [also] character fortitude. It is about curiosity – opening minds; it is about compassion – opening hearts; and it is about courage—mobilising our cognitive, social and emotional resources to take action. These qualities, or social and emotional skills, as our report calls them, are also weapons against the greatest threats of our time: ignorance – the closed mind; hate – the closed heart; and fear – the enemy of agency. (p. 3)

Knowledge evaluations can be made through comparative international knowledge tests such as PISA (the Programme for International Student Assessment), PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) and TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study). These tests produce their own performance data. Based on these data, countries are ranked according to their students’ test results. Regarding teachers’ grading, tools and practices have been developed and institutionalised over time. Grades are set by the individual teacher and are thus dependent on the teachers’ knowledge, understanding, values and other factors. Accordingly, grades are not measures of objectively valued knowledge. With grades, however, summative results can be presented that can be used to compare the knowledge levels of different students. Although there is movement towards being able to measure personal development as well, this has not yet come this far (Williamson, Citation2017). Therefore, measurements and comparisons of students’ personal development still seem unusual today.

As noted, there are now high expectations of improved knowledge results, which the actors in the local multilevel governance chain are responsible for meeting (Bryk et al., Citation2015; Rapp et al., Citation2020). To meet these high expectations, tests as well as performance and grade measurements are performed that affect students’ levels of stress, self-esteem and general health (Högberg et al., Citation2019).

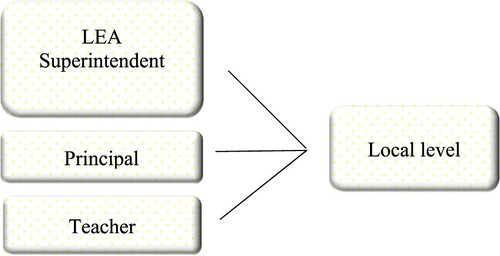

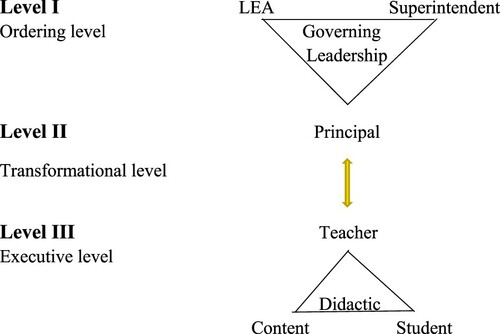

The legal responsibility for implementing the normative arrangements lies with all the actors in the local governance chain. This chain can be divided into three levels: (i) the ordering level (the LEA and the superintendents); (ii) the transformational level (the principals); and (iii) the executive level (the teachers). In addition to formulating and issuing orders for all local schools to fulfil legal requirements, the first level acts as an enabler (allocates resources) and controller (monitors results). On the next level, principals are expected to take responsibility for ensuring that the work in their school meets the legal requirements. At the third level, teachers are expected to execute or implement the national and local requirements.

This study is interested in the two legal normative requirements: (i) students’ knowledge development and (ii) students’ personal development. The main purpose of this study is to explore how a local governance chain’s actors work to realise these two normative requirements. Its other purpose is to find out more about the tensions and power struggles that can arise in a governance chain during its implementation of the normative national requirements and what effects these tensions can have. The research questions of this study are as follows:

- How do the ordering level, the transformational level and the executive level prioritise and act with regard to the Education Act’s normative requirements for developing students’ knowledge and for developing students as persons?

- What tensions and power struggles can arise when implementing such requirements and what are their possible effects?

To fulfil this study’s purposes and to find answers to its questions, a case study was conducted in a small town in southern Sweden in 2020. In this study, empirical data were collected from actors in a local governance chain responsible for compulsory schools (with students aged 6–16 years).

Knowledge development and personal development in Sweden

The first Swedish Curriculum for the Compulsory School (Lgr 62. Läroplan för grundskolan, Citation1962) stated that the schools’ activities must be designed in a way that promotes their students’ personal development. The opportunity for personal development was seen as a motivational factor; and in the early 1970s, motivation came to be defined as students’ goals for their schoolwork and their personal development (Giota, Citation2013). In the Curriculum for Compulsory Schools 1980 (Lgr 80. Läroplan för grundskolan, Citation1980), the importance of the student’s motivation or goals for schoolwork was emphasised as a prerequisite for learning. In the subsequent curriculum (Lpo 94. Läroplan för det obligatoriska skolväsendet, Citation1994), the importance of promoting each student’s personal development and learning was emphasised (Giota, Citation2013). However, in the latest curriculum, Lgr 11 [National Agency for Education (NAE), Citation2011], there was a shift from a humanist perspective that emphasised personal development to academic rationalism that emphasises subject knowledge (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015, p. 68).

This study examines what has turned out, in our search for literature, to be a rarely recognised feature in the Swedish Education Act. It was difficult to find previous research that dealt in parallel with the concepts of knowledge development and personal development. There are plenty of studies on students’ knowledge development, from different perspectives (Giljers & de Jong, Citation2005; Mårtensson, Citation2015; Todd, Citation2006). However, in terms of students’ personal development, it was more difficult to find relevant research for this study. The NAE (Citation2009) has produced an overview of what factors affect schools’ knowledge results; and regarding students’ personal development, different conditions for such are emphasised, that is, influencing factors outside the school (e.g. the family’s conditions and the influence of peers). For example, the overview states that the teaching must be adapted to the student’s conditions.

The Swedish school system, norms and leadership

In the 1990s, the Swedish school system changed from being one of the Western world’s most centralised school systems to one of its most deregulated (NAE, Citation2009). Municipalities took over its leadership, and at the same time that its responsibility was decentralised, goals and results management were introduced. Since then, Swedish schools have been managed with a hierarchical top-down perspective that is often referred to as “New Public Management” (NPM), the key words of which are norms, goals, results, control and accountability (Hood & Dixon, Citation2015). For the school, NPM means that the students’ results are checked on the basis of legal norms and set goals. If the goal fulfilment is deemed substandard, the LEA is legally accountable for improvement efforts. The LEA, in turn, can hold principals and teachers accountable for students’ goal fulfilment.

Norms can be questioned, and the concept of normalisation can arouse strong negative emotions in today’s individualistic society (Nilholm, Citation2012). The existence of norms becomes visible only when they collide with other actors’ norms (cf. ethnomethodology; Garfinkel, Citation1984). However, if one sees normalisation as an adaptation to norms, it is obvious that we all devote ourselves to such a process (Nilholm, Citation2012). In this study, the concept of a norm is based on the school’s legal governance, and normality is used as a value-neutral concept.

In the governance chain, decision-making power is distributed, as established in schools’ statutes. At a rhetorical level, most people probably agree that governance should be exercised in accordance with legal norms. Nevertheless, when these norms are to be applied in a local school system, the legal order can be met by a lack of legitimacy, which, in turn, can lead to resistance (Rapp, Citation2021). This is shown, for example, in the supervisory reports of the Swedish Schools Inspectorate, where LEAs are largely criticised for not ensuring that schools meet the national requirements. Such criticism may be directed at a LEA due to its responsibility for schools’ results, that is, for the students’ knowledge development.

A school’s governance is seen, among other things, in its educational leadership (Ståhlkrantz, Citation2019). This leadership is exercised at all levels in a multilevel school system (Fullan, Citation2015; Uljens et al., Citation2016; Uljens & Ylimäki, Citation2015). Furthermore, educational leadership can be exercised in several different ways – for example, as transactional leadership (based on job descriptions, quality standards etc.; Rapp, Citation2021); transformational leadership (based on visions, goals, support, high expectations, an improvement culture etc.; Leo, Citation2013); or instructional leadership (focusing on the teaching; Coldren & Spillane, Citation2007; Robinson, Citation2017; Timperley, Citation2011; Timperly et al., Citation2020). All leadership includes the exercise of power. It has different elements and emphases, which are discussed further under the next heading.

Power and resistance

The idea of schooling as important for a democratic society is essential to the governance of Swedish education (NAE, Citation2011). Democracy is basically distributed power. From a normative perspective, governance is based on a “disciplinary power” (Foucault, Citation1979). Accordingly, the concept of power includes “power to [do something]” and “power over [someone]”. The goal of power is to shape people so that they act in line with both stated and unspoken rules (Hoffman, Citation2014). Power is exercised in relationships, becomes visible through actions and requires abilities for its execution (Reason, Citation1998).

“Power to,” which means ability or capacity, is a prerequisite for the exercise of power and becomes visible when one is trying to convince someone to act in a specific direction (Pasardi, Citation2012). In this study, “power to” can be considered a discursive power (referring to the legality of governance, teaching and control). “Power over” is more about the ability to directly influence another person or situation. Here, a real power may emerge that intervenes in the life of an individual or a group (Pasardi, Citation2012).

The national distribution of power is expressed by the decisions of parliament and government and reflected in schools’ statutes. In addition, the national level provides schools both support (from the NAE and the Agency for School Development; NAE, Citation2021) and control (through the Swedish Schools Inspectorate). At the local level, the LEA has the overall responsibility for everything from school premises to students’ goals fulfilment (Moos & Merok Paulsen, Citation2014; Rapp et al., Citation2020). Superintendents assist the LEA, and they are also often the head of the principals (Rapp, Citation2011; Ståhlkrantz & Rapp, Citation2020). Principals are responsible for their school and are the pedagogical leader of their teachers (Pashiardis & Johansson, Citation2016; Rapp, Citation2010; Ståhlkrantz, Citation2019). Licenced teachers are responsible for the teaching, and their work has a decisive effect on both students’ learning and motivation (Mausethagen, Citation2013; Nilholm, Citation2012).

To summarise, in a school’s statutes, school actors are given legal power. This discursive power must be applied by the actors, and it is in the application that the real power becomes visible. The main aim of this study is to investigate the application by schools’ local governance chain actors of their discursive power to drive both students’ knowledge development and personal development.

Theoretical framework

A governance chain can be regarded as a social organisation where actors construct their own understanding based on their lifeworlds (Bengtsson & Berndtson, Citation2015; Marton, Citation1981; Schutz & Luckmann, Citation1974; Schwandt, Citation1998). The actors socialise in networks at their own levels and at other levels (e.g. principals collaborate with superintendents, and teachers collaborate with principals). In both level-minded and level-breaking networks, meetings can affect the actors’ understanding of their lifeworlds. At the same time, the precondition for maintaining a common social world is the actors’ reaching of a consensus on the nature of the world (Nilholm, Citation2012). If there is unity as regards legal norms, these legal norms will also constitute a framework for action.

From a rationalistic normative point of view (Abrahamsson, Citation1975; Abrahamsson, Citation1992), the actors of the local governance chain are expected to execute national legal requirements. At the same time, the principal-agent theory (Ferris, Citation1992) shows that activities in multilevel organisations are often largely built around autonomous professionals. This is supportive of a loose coupling between levels in the chain (Boyd & Crowson, Citation2002; Fuzarelli, Citation2002; Meyer, Citation2002; Weick, Citation1976). Furthermore, according to the principal-agent theory, a governance chain is built upon asymmetric power relations (Rapp et al., Citation2020), which means that the information and knowledge of the actors at each level are superior to those of the actors at the upper levels. An example of this is when teachers (as agents), depending on their knowledge superiority, independently determine the content and design of their classroom work. This reveals that in such a governance chain, it cannot be taken for granted that an agent is acting in accordance with a principal’s interests (Ferris, Citation1992). This phenomenon applies to the connections between all levels in the chain.

From LEA governance to classroom didactics

In the introductory part of this paper, it was mentioned that the local governance chain could be divided into three levels: (i) the ordering level (the LEA and the superintendents); (ii) the transformational level (the principals); and (iii) the executive level (the teachers) (see ). Furthermore, it was established that LEAs and superintendents determine conditions and follow up on schools’ results, the principal provides the link between the LEA and the superintendents, and the local schools and teachers are responsible for teaching and learning. A school’s organisation is thus divided into three levels to show how legal governance is theoretically linked to the didactic efforts of teaching (see ).

The governance and leadership triangle (Level I) is based on a perspective that is NPM-inspired and is driven by legal goals and results. It is here where the ultimate responsibility for the education provided by local schools rests. At Level II, principals are expected to transform, mediate and control the implementation of political decisions in schools. This implementation appears in the didactic triangle (Level III), where teachers and students meet. Here, teachers decide on the teaching content (what) and which methods to use (how). At the same time, they must critically examine both the content and the implementation of the teaching (why). In a teaching situation, it is a teacher’s beliefs and values that determine how didactic questions will be answered (Argyris, Citation1999; Robinson, Citation2017; Timperly et al., Citation2020).

Methods

This case study (Yin, Citation2009) was conducted in a town (“municipality”) in an urban area (Sveriges Kommuner och regioner, Citation2016) in the south of Sweden at the start of 2020, among the actors in the local governance chain for compulsory schools (pre-school to school year 9). The municipality – the object of study – was chosen after several conversations with the chair of the LEA. Central to the choice of study object was the LEA's interest in gaining increased knowledge about the effectiveness of the governing of its own school organisation. This interest coincided with the purpose of this research and thus provided good conditions for cooperation in the implementation of this study. For the LEA, an additional purpose was to use the results of this study as the basis of its future improvement work.

The empirical data were collected from interviews of the LEA’s chair and vice chair, the superintendent and deputy superintendent, four principals and nine teachers. The interviewees are collectively referred to in this article as “actors in the chain of governance.” They were made up of an equal number of women and men, all of whom had worked for at least five years in the same position.

The interviews were semi structured (Cohen et al., Citation2018) and an interview guide provided the researcher an opportunity to further explore areas of interest. The interviewees were asked to describe the local school practice and their expectations of the actors at the other levels of the governance chain. The goal was to document stories to expose different (dominant) discourses (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation1998). Each interview took between 45 and 70 minutes, was both exploratory and descriptive, and was recorded and transcribed in its entirety. The transcribed material was subsequently processed and analysed to find in-depth explanations of the phenomena. In the first step of the transcription processing, the texts were read to get an overview, and parts of special interest were identified. Then the texts were re-read and categorised under thematic headings based on the study’s aims and questions.

Ethical decisions were made on various occasions during the process (Vetenskapsrådet, Citation2017). Prior to the interviews, all the interviewees were informed about the subject, purpose and methodology of this study; the storage, use and safekeeping of their data; and their prerogative to withdraw from this study at any time.

However, conducting a case study in a municipality poses direct challenges in terms of confidentiality. Even if the investigated municipality is not named, some people would know which municipality is being referred to. Thus, some of the interviewees risked becoming identifiable, such as those who held political positions and the senior officials (i.e. the superintendents). To ensure that no one would be identified against his or her will, both the politicians and the superintendents were informed about the confidentiality issue. Despite this risk, they all gave their consent to participate in this study and to have their answers published in this research paper.

The chair, vice chair, superintendent and deputy superintendent read their printed interview texts and had the opportunity to comment on them. This was done for three reasons. The first was to ensure that there were no errors in the transcribed texts. The second reason was to avoid writing anything that could be perceived as troublesome for the interviewees, who could be recognised. The third reason was to allow them to supplement their responses in order to deepen the readers’ understanding of particularly important issues. Only one of the interviewees requested certain adjustments. These were editorial in nature and did not change the content of the original text. A side effect of the interviewees’ text review was that the validity of this study was strengthened.

Results

The hierarchical school governance chain is based on the assumption that what is legally decided will be implemented in schools. For this to happen, the actors in the local multilevel chain must fulfil their responsibility and implement what is stated in the school statutes.

In the municipality investigated, the LEA is responsible for compulsory schools, and a chair and a vice chair represent its management. A superintendent and a deputy superintendent assist the LEA. Together, these politicians and officials comprise the ordering level (Level I). Each school has a principal, who represents the transformational level (Level II). Teachers are directly responsible for teaching and learning and make up the executive level (Level III).

In the following sections, the results of the interviews are presented. The results are organised under the three aforementioned levels: the ordering level, the transformational level and the executive level.

Level I: ordering level

The LEA’s mission is to support schools and to control their results so that they would achieve their goals as stipulated in their statutes. Thus, the LEA’s work is focused on overall organisational governance. The chair has high ambitions in terms of students’ knowledge development (i.e. the achievement of improved merit values) and wellbeing, and wants the available financial resources to be primarily given to teachers. The chair expressed this as follows: “If we can support them in everything they want, then it beats everything else in principle.”

The chair of the LEA is assisted by the superintendent, who prepares the political decision-making documents. This means that the superintendent has vast opportunities to influence both political proposals and decisions. The superintendent is the leader of the principals and has high expectations of each of them. He said all the principals know that only one thing counts: their students’ improved merit values: “What I focus on all the time, it’s really the only thing I care about; if you ask me, it’s how high a merit value the student can get.”

The superintendent further argued that if principals have their student results in order, if they have satisfied employees and if they have “the money in place,” they “can do almost what they want.”

The superintendent exercises his leadership, his discursive “power to” affect the teaching, by implementing the LEA’s decisions and controlling the outcomes. That the ordering level does not have a direct “power over” the teachers is shown when the superintendent argues that developing the teachers’ teaching is a major task of the principals. If principals need support in terms of their educational leadership work, the administration can help them by providing staff with the needed skills.

There are many challenges in being the superintendent in a school organisation. One such challenge is the principals’ loyalty when it comes to the implementation of the LEA’s decisions. When the superintendent presents a political decision, he knows that about 20% of the principals will think that the decision is great, 60% will think it is acceptable and 20% will disapprove of it. He said, “This is the case for all matters”; and as a result, the principals’ attitudes will affect the implementation of the decision.

Level II: transformational level

One of the principals’ main tasks is to connect the ordering level and the executive level. However, the principals do not have many meetings with the LEA. Principal 4 said, “The political level is invisible; they never visit us.”

The principals’ connection to the political level is channelled via the superintendent, and the superintendent thus forms a boundary between the principals and the LEA. Several principals see this arrangement as positive because they want protection from the political level. For example, Principal 1 had asked the superintendent to act as the principals’ “gatekeeper against the politics” and to support them in working in line with their national assignments.

In their transforming role, principals have the discursive “power to” direct and control the teacher. If they are sufficiently pedagogically skilled, they can even exercise “power over” teachers to directly influence teaching (Pasardi, Citation2012). This study’s results showed that principals can act and support the goal of continuously improved merit values in various ways. In some cases, they choose to work directly with educational leaders, including through classroom visits and personal conversations with teachers. In other cases, principals choose to work more indirectly, such as on security measures, which can involve spending time in the corridors and meeting students day to day (Principal 4).

The most central aspect of students’ knowledge development is good teaching. Consequently, the principals’ most important leadership task is to recruit skilled teachers and continuously support the development of their competencies (Principal 2).

The principals were well aware of the ordering level’s requirements concerning the need to continuously improve students’ merit values. Nevertheless, the perceptions of this focus differed. Some of the principals expressed their belief that education should involve more than the pursuit of higher grades. One principal believes that school leaders’ different perceptions of grades are ideologically based, and some are critical of assessing “at such young ages” (Principal 3). For students to succeed, they must feel good and thrive in school, and Principal 1 said he sometimes feels frustrated about how “students are doing” and that it is pointless to try to improve their performance if they are not happy: “What affects me negatively is when you do not put the students at the centre.”

As transformers, principals can decide on the direction they will take in their work. This means a principal can influence how much teachers focus on students’ knowledge development and on students’ personal development.

Level III: executive level

The teachers stated that their contact with the ordering level is channelled via the principal (at the transformational level) and that they hardly have contact with politicians or superintendents. For example, Teacher 9 said that in her 30 years in the school, only one politician had visited her. Nor did they see any real benefits in meeting the politicians (Teacher 7). Teacher 4 mentioned that it is important to be supported by the ordering level, and she has low expectations of both the LEA and the superintendent regarding leadership.

When teachers in this study talk about educational leaders (i.e. instructional leaders), they primarily refer to principals. At the same time, teachers’ expectations of the elements of educational leadership differ. A principal can be a part of the implementation and development of teaching by following teachers’ work and visiting classes (Teacher 8). Other teachers argued that they are “used to working very much alone” and do not want anyone else in their classrooms (Teacher 2). There are also teachers who believe that principals do not influence their work at all, as, for example, Teacher 6, who said, “No, because I always say what I think and feel.”

To fully achieve the legal goals, the administration is expected to provide good conditions for teachers’ instruction. One condition is to remove non-teaching-related tasks as much as possible. The governance chain is based on each level taking responsibility. This means that principals take responsibility for their unit and carry out what the administration instructs. Teacher 5 said it cannot always be assumed that principals are loyal to decisions taken at the ordering level: “I think they (the principals) probably present certain things from the angle that they want.” This was supported by Teacher 7, who believes that principals convey political and administrative decisions and ambitions in different ways. Principals “want to run their schools in their own way” and are responsible for their own schools’ internal organisation. Teacher 7 feels “chased” and said, “Leave us alone, do not be on our backs all the time,” which shows that driving development in a governance chain while encouraging the chain’s actors to follow is a balancing act (Teacher 4).

Teachers’ attitudes to strong control regarding improved student merit values differ. Some are positive, and one said their municipality is doing well compared with other municipalities (Teacher 2). In the other teachers’ answers, a certain degree of fatigue could be felt. Teacher 7 said, “Yes, accepted, so yes, what should we do?” The teacher further says that the LEA controls and one follows what they decide. However, there were also teachers who criticised directly this strong control pertaining to improved student merit values. Teacher 9 said too much is measured and the effect of it is stressed students and teachers. Teacher 4 said, “It is on the verge of too high expectations where you feel hunted.” Teacher 4 further criticised the frequent measurement of results: “You also need peace of mind in your working environment, you cannot see week by week, month by month how the development is going for students.” Teacher 4 feels that the administration “chases the principals, the principals chase the teachers and the teachers chase the students.” Teacher 6 expressed irritation with the focus on merit values and said at one point, “I do not care if they say you have to raise the merit values, you have to raise the grades; I actually do not listen to that. I’m doing as well as I can … .” Teacher 7 is “extremely tired of this measurement” and says it is ridiculous when you have grades of between 98.8 and 99.1. The teachers also question whether knowledge and knowledge development should be shown only in terms of credit points. Teacher 6 said, “Students can develop and gain more knowledge without getting higher credit points,” and Teacher 8 said a student who gets a grade of C and one who gets a B can have the same level of knowledge.

Requirements for improved merit values also spill over to the students, some of whom become stressed. Teacher 5 was concerned about the risk of students being stressed and said: “I feel that you are so small; it is great that you do your best, I really want you to do your best, but do not lie sleepless if you get a B or a C.”

The requirements that the teachers were given from the higher levels are exclusively about increased merit values. The second requirement regarding the students’ personal development hardly emerged during the interviews.

Analysis and discussion

This study investigated normative legal requirements in Swedish schools, how local governance chain actors work to realise such requirements and what tensions and power struggles can arise during this process.

The governance observed in the investigated municipality is based on a rationalistic approach, is hierarchically organised and is strongly influenced by NPM. The LEA and the superintendent (the ordering level) control by setting goals, allocating resources and following up on results (transactional and transformational educational leadership). The overriding and communicated goal is that of improving students’ grades and thus, continuously increasing students’ merit values. The superintendent has conditioned the division of power, having said that if principals have their student results in order, if they have satisfied employees and if they have financial control, they “can do almost anything they want.” The division of power is based on control, and the ordering level’s interest is entirely focused on the first normative legal requirement, the students’ knowledge development. The normative requirement for the students’ personal development is not visible at this level.

At the transformational level, a more mixed picture was presented. Here, some principals agreed on the need to focus on merit values, but others were more critical. The latter highlighted the importance of students thriving and feeling safe in school. Thus, at the transformational level, the focus is on improved merit values, but at the same time, the students’ need for personal development is made visible. Here, one can assume that there is some criticism and some resistance to an overly one-sided focus on merit values.

At the executive level, instructional leadership is exercised, and the Education Act’s two normative requirements for students’ knowledge development and personal development are supposed to be realised. The task of teachers, as set by the ordering level, is to improve students’ merit values. Requirements for working on students’ personal development are not expressed by the ordering level. Teachers’ perceptions of the ordering level’s focus on merit values vary, ranging from positive to negative, and their feelings are related to stress. At this level, the opposition to the one-sided focus on results is apparent. Higher merit values do not guarantee increased knowledge, and “chasing” students to improve their grades does not contribute to their personal development.

In a legally regulated activity, it is assumed that governance is exercised in accordance with the prevailing norms. However, schools’ legal framework regulations provide the opportunity for different interpretations, and the actors can, without being in conflict with the statutes, decide on their own priorities. This means that the underlying levels in the chain can establish priorities that are not fully aligned with the decisions made by the upper levels (c.f. loose couplings). Such priorities imply resistance and thus, challenge the legitimacy of the upper levels. This was shown in this study when the teachers explicitly stated that they do not intend to work in accordance with the ordering level’s focus on improving merit values, which the principals suggested.

The national normative governance of education is focused on both students’ knowledge development and their personal development. However, in the investigated municipality, the interest seems to be mainly directed towards summative measurable knowledge development and grades (e.g. international knowledge measurements). This is also evidenced by the fact that national support is offered to schools that achieve low knowledge results (NAE, Citation2021), while no targeted support is given for students’ personal development. Furthermore, offering targeted national support for students’ personal development is difficult because such type of need is not being mapped. Accordingly, there is a weak basis for such support. Against this background – the national focus on students’ knowledge development and the poor interest in students’ personal development – it is understandable that local governance chains’ top level (the ordering level) focuses on improving merit values.

The actors at the different levels appear to be in different lifeworlds based on different realities. In the ordering level’s lifeworld, those who are to improve their merit values (the students) are not explicitly visible. Accordingly, this level can distance itself from the challenges that come with teaching students and with considering their personal needs and challenges. The transforming level (the principals) must act to meet the ordering level’s requirements for improved merit values. At the same time, the principals meet their schools’ teachers and take part in their work with the students. This means that principals have personal knowledge of the teachers’ challenges in terms of meeting the students’ personal needs. The teachers (at the executive level) meet the students and experience face-to-face how the students feel when they are pressured to strive for higher merit values. From teachers' lifeworld experiences, the great focus on merit values means that they might feel hunted and stressed. These feelings are transmitted to the students, which can have consequences for the overall health of pupils. This result is in good agreement with the conclusions of Högberg et al. (Citation2019).

It is against the background of these divergent lifeworlds that one can understand the actors’ different positions; and it is here that the effects of the prevailing asymmetric distribution of power become visible (cf. the principal-agent theory). That there is awareness of the effects of the principal-agent theory is indicated at all levels in the governance chain. The superintendent showed it through the statement that “The principals’ attitudes will affect the implementation of the decision” (Results, Level I). Furthermore, the principals can decide how to influence teachers in their priorities (Results, Level II), and the teachers independently prioritise the content of their teaching (Results, Level III). The application of governance appears in the classroom (instructional leadership) when a teacher meets his or her students. Here, the teacher (the agent) is autonomous and decides what to prioritise. The degree of influence in relation to the control coming from above (transactional and transformative leadership) will become visible in a teacher’s instructional leadership. This shows how a teacher (the agent) finally determines what to prioritise.

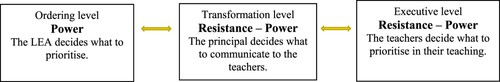

In this study, power is considered from two perspectives: (i) discursive power (based on legal regulations) and (ii) real power (who makes the final decision). The actors in a local governance chain are assumed to work together to support students’ knowledge and personal development. The upper level has a legal right to make decisions that should be implemented at the lower levels. At the same time, the underlying levels have the opportunity to resist the decisions made. Accordingly, the extent to which a decision is implemented becomes an empirical question. The relationship between power and resistance in the governance chain is shown in .

The concepts of power and resistance can be used as metaphors to understand what happens in meetings between the actors’ lifeworlds at different levels in a governance chain. Each level has its discursive legal powers that can be exercised against the underlying levels. The ordering level has legal power to demand improved merit values and can give orders to the principals (at the transformational level). The principal has assignments from both the national and local levels and sets priorities before making demands on the teachers (at the executive level).

The teachers decide on their teaching content and implementation, and they can resist the priorities given. Teachers’ priorities (cf. the didactic triangle in ) can be shaped by their own values; and for as long as their actions are within the broad legal framework, their actions cannot be considered illegitimate (cf. “free space”; Berg, Citation2018).

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of power rather than its intentions. According to the discursive rationalistic approach, decisions are made at the upper level and implemented by the underlying level(s). However, the results showed that this way of governance is challenged in school practice. If the transformational level and, especially, the executive level do not share the ordering level’s intentions (values and beliefs), they can resist. With the limited opportunities for correction that come with the discursive division of power, the ordering level cannot ensure that teachers will follow the orders given. Despite the LEA having the legal responsibility for all local schools, it has limited opportunities for the exercise of power. Here, the conditions for the real division of power become visible, and discursive power risks being regarded as symbolic. Accordingly, the model of the rationalistic NPM-inspired division of power does not necessarily work as intended.

To sum up, the results of this study showed that all levels in the governance chain mainly speak of the first normative requirement – students’ knowledge development. Some teachers and principals said unreasonable demands for ever-increasing merit values lead to stress among students and teachers. Demands were made to reduce focus on knowledge and increase focus on the students’ wellbeing. This shows the power struggle that prevails with respect to the requirement for students’ knowledge development. The second normative requirement, students’ personal development, is not explicitly discussed at any level in the governance chain. It is possible that work with personal development is implicit in the education programme, but as it is not communicated, evaluated or followed up, there is a lack of knowledge of the practical significance of such requirement. As the legal requirement is not discussed, it cannot lead to a power struggle between the levels of the power chain.

With the study’s questions answered, it is time to look ahead. The results showed that the focus is on the first normative Education Act requirement (students’ knowledge development), while discussions about the second normative legal requirement (students’ personal development) are missing. This leads to the question of how schools address demands for work on achieving students’ personal development – a question that is interesting to delve into in a future study.

Limitations

This case study was intended to investigate the entire chain of governance in Swedish schools, which is both interesting and relevant, as the conditions within schools, in the form of expectations, educational leadership and students’ knowledge development, were to be explored. However, the empirical material was collected in only one municipality, and therefore, the results cannot be generalised, and conclusions cannot be drawn based on a positivistic research ideal. However, for this study, transferability is more important than generalisation. It is the recipient of the results (the reader) who decides on its transferability (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). This makes the findings recognisable and possibly comparable with the findings of other studies and with one’s own experiences. Thus, this research can make a valuable contribution to further studies on this subject. Depending on the readers’ experiences, the results can be transformed into both the national and international contexts.

Even if this study was aimed only at public schools, it should be mentioned that a large proportion of Sweden’s schools are independent and run by private owners. In the academic year 2019–2020, independent compulsory schools accounted for only over 20% of all compulsory schools in Sweden (NAE, Citation2020). The financing of these schools takes place through government grants, and independent schools receive the same amount of money per student as publicly run schools. All schools, both public and private, are operated in a competitive system, and what can be compared are their student’s final grades. Many of the independent schools have financial profit interests. Whether this affects the schools’ work with the students’ knowledge development and personal development is not part of the results of this study. However, this may be interesting to investigate in future studies.

A third limitation of this study is the researcher’s experience of the school system. In addition to a research background, the researcher has extensive experience as a teacher, principal and superintendent. This background was beneficial in understanding and interpreting the findings but, at the same time, posed the risk of this process being coloured by the researcher’s own experiences and of the researcher’s pre-understanding obscuring perspectives of someone with a different background.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrahamsson, B. (1975). Organisationsteori. Om byråkrati, administration och självstyre [Organizational theory. About bureaucracy, administration and self-government]. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Abrahamsson, B. (1992). Varför Finns organisationer? Kollektiv handling, yttre krafter och inre logik [Why are there organisations? Collective action, external forces and internal logic]. Studentlitteratur.

- Argyris, C. (1999). On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Blackwell Business.

- Bengtsson, J., & Berndtson, I. (Eds.). (2015). Lärande ur ett livsvärldsperspektiv [Learning from a life-world perspective]. Gleerups.

- Berg, G. (2018). Skolledarskap och skolans frirum (2nd ed.) [School leadership and schools’ free space]. Studentlitteratur.

- Boyd, W. L., & Crowson, R. L. (2002). The quest for a new hierarchy in education: From loose coupling back to tight? Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210446018

- Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve. How America’s schools can get better in getting better. Harvard Education Press.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Coldren, A., & Spillane, J. (2007). Making connections to teaching practice. Educational Policy, 21(2), 369–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904805284121

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1998). The landscape of qualitative research. SAGE.

- Ferris, J. M. (1992). School-based decision making: A principal-agent perspective. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(4), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737014004333

- Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish. The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

- Fullan, M. (2015). Coherence. The right drivers in action for schools, districts, and systems. Corwin.

- Fuzarelli, L. D. (2002). Tightly coupled policy in loosely coupled systems: Institutional capacity and organizational change. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 561–575. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210446045

- Garfinkel, H. (1984). Studies in ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

- Giljers, H., & de Jong, T. (2005). The relation between prior knowledge and students’ collaborative discovery learning processes. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20056

- Giota, J. (2013). Individualiserad undervisning i skolan – en forskningsöversikt. Vetenskapsrådets Rapportserie 3:2013 [Individualised teaching in school – A research review].

- Hart, S. N., Price Cohen, C., Farrel Erickson, M., & Flekköy, M. (Eds.). (2001). Children’s rights in education. Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

- Hart, S., & Pavlovic, Z. (1991). Children's rights in education: An historical perspective. School Psychology Review, 20(3), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1991.12085558

- Hoffman, M. (2014). Foucault and power. The influence of political engagement on theories of power. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Hood, C., & Dixon, R. (2015). A government that worked better and cost less? Evaluating three decades of reform and change in UK central government. Oxford University Press.

- Högberg, B., Lindgren, J., Johansson, K., Strandh, M., & Petersen, S. (2019). Consequences of school grading systems on adolescent health: Evidence from a Swedish school reform. Journal of Education Policy, 36(1), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1686540

- Leo, U. (2013). Rektors pedagogiska ledarskap. En kunskapsöversikt. Forskning i korthet, 2013:4 [Principals’ pedagogical leadership. A knowledge overview. Research in brief 2013:4]. Kommunförbundet i Skåne.

- Lgr 62. Läroplan för grundskolan. (1962). [Curriculum for compulsory school 1962]. Skolöverstyrelsens skriftserie 60. SÖ-förlaget.

- Lgr 80. Läroplan för grundskolan. (1980). [Curriculum for compulsory school 1980]. Skolöverstyrelsen och Utbildningsförlaget.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications.

- Lpo 94. Läroplan för det obligatoriska skolväsendet (1994). [Curriculum for the compulsory school system]. Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Marton, F. (1981). Phenomenography ? Describing conceptions of the world around us. Instructional Science, 10(2), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00132516

- Mausethagen, S. (2013). A research review of the impact of accountability policies on teachers’ workplace relations. Educational Research Review, 9(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.12.001

- Mårtensson, P. (2015). Att få syn på avgörande skillnader. Lärares kunskap om kunskapsobjektet. [Learning to see distinctions: Teachers’ gaining knowledge of the object of learning]. School of Education and Communication Jönköping University. Dissertation Series No. 29.

- Meyer, H.-D. (2002). From “loose coupling” to “tight management”? making sense of the changing landscape in management and organization theory. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 515–520. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210454992

- Moos, L., & Merok Paulsen, J. (Eds.). (2014). School boards in the governance process. Springer.

- National Agency for Education. (2009). Vad påverkar resultaten i svensk grundskola? Kunskapsöversikt om betydelsen av olika faktorer Sammanfattande analys [What influences educational achievement in Swedish schools? A systematic review and summary analysis]. Swedish National Agency for Education. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/kunskapsoversikter/2009/vad-paverkar-resultaten-i-svensk-grundskola-kunskapsoversikt-om-betydelsen-av-olika-faktorer.?id=2260

- National Agency for Education. (2011). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2011. [Curriculum for compulsory school, pre-school classes and leisure centers]. https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/grundskolan/laroplan-och-kursplaner-for-grundskolan/laroplan-lgr11-for-grundskolan-samt-for-forskoleklassen-och-fritidshemmet

- National Agency for Education. (2020). Elever och skolenheter i grundskolan läsåret 2019/20. [Students and school units in compulsory school in the 2019/20 academic year]. https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6b138470170af6ce9149d0/1585039519111/pdf6477.pdf

- National Agency for Education. (2021). Samverkan för bästa skola [Cooperation for the best school]. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/leda-och-organisera-skolan/samverkan-for-basta-skola

- Nilholm, C. (2012). Makt, motstånd och normalisering – En kommentar [power, resistance and normalisation – A comment]. Utbildning & Demokrati, 21(3), 107–111.

- OECD. (2021). Beyond academic learning: First results from the survey of social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/92a11084-en

- Pasardi, P. (2012). Power to and power over: two distinct concepts of power? Journal of Political Power, 5(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.658278

- Pashiardis, P., & Johansson, O. (Eds.). (2016). Successful school leadership. International perspectives. Bloomsbury.

- Quennerstedt, A. (2010). Den politiska konstruktionen av barnets rättigheter i utbildning. [The political construction of the child’s rights in education]. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige, 15(2/3), 119–141.

- Quennerstedt, A. (2013). Children’s rights research moving into the future – challenges on the way forward. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 21(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02102006

- Rapp, S. (2010). Headteacher as a pedagogical leader: A comparative study of headteachers in Sweden and England. British Journal of Educational Studies, 58(3), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071001003752229

- Rapp, S. (2011). The director of education as a leader of pedagogical issues: A study of leadership in municipal educational sector activities. School Leadership & Management, 31(5), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2011.587405

- Rapp, S. (2021). Att leda elevers kunskapsutveckling. Styrkedjan och det pedagogiska ledarskapet [To lead students’ knowledge development. The governance chain and pedagogical leadership]. Gleerups Utbildning AB.

- Rapp, S., Aktas, V., & Ståhlkrantz, K. (2020). Schoolboards’ expectations of the superintendent – A Swedish national survey. Educational Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2020.1837740

- Reason, P. (1998). Three approaches to participative inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (pp. 261–291). SAGE.

- Robinson, V. (2017). Reduce change to increase improvement. Corwin.

- Schutz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1974). The structures of the life-world. Heinemann Educational Books.

- Schwandt, T. A. (1998). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 221–259). SAGE.

- SFS. (2010:800). Skollagen. [Education Act]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

- Ståhlkrantz, K. (2019). Rektors pedagogiska ledarskap – En kritisk diskursanalys. [principals’ pedagogical leadership – A critical discourse analysis]. [Doctoral dissertation]. Linnaeus University Press. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1272783/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Ståhlkrantz, K., & Rapp, S. (2020). Superintendents as boundary spanners – facilitating improvement of teaching and learning. Educational Administration & Leadership REAL, 5, 376–415. https://doi.org/10.30828/real/2020.2.3

- Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner. (2016). Kommungruppsindelning 2017. Omarbetning av Sveriges Kommuners och Landstings kommungruppsindelning. [Sweden’s municipalities and regions. Municipal Group Division 2017. Rework of Sweden’s municipalities and county councils’ Municipal Group Division]. Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting.

- Timperley, H. S. (2011). Knowledge and the leadership of learning. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(2), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2011.557519

- Timperly, H., Ell, F., Le Fevre, D., & Twyford, K. (2020). Leading professional learning. Practical strategies for impact in schools. Australian Council Educational Research.

- Todd, R. J. (2006). From information to knowledge: Charting and measuring changes in students’ knowledge of a curriculum topic. Information Research, 11(4), paper 264. http://InformationR.net/ir/11-4/paper264.html

- Uljens, M., Sundqvist, R., & Smeds-Nylund, A.-S. (2016). Educational leadership for sustained multi-level school development in Finland – A non-affirmative approach. Nordic Studies in Education, 36(2), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-5949-2016-02-03

- Uljens, M., & Ylimäki, R. (2015). Theory of educational leadership, didactic and curriculum studies – A non-affirmative and discursive approach. In Educational leadership – Theory, research and school development (pp. 103–128). Report from the Faculty of Education and Welfare Studies, Åbo Akademi University (No. 38).

- United Nations [UN]. (1989). Convention on the rights of the Child (1989) treaty No. 27531. United Nations Treaty Series, 1577, 3–178.

- Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). God forskningssed [Good research practice]. https://www.vr.se/download/18.2412c5311624176023d25b05/1529480532631/God-forskningssed_VR_2017.pdf

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2015). Theory-based evaluation of the curriculum Lgr 11. IFAU. https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2015/wp2015-11-theory-based-evaluation-of-the-curriculum-lgr_11.pdf

- Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

- Williamson, B. (2017). Decoding ClassDojo: Psycho-policy, social-emotional learning and persuasive educational technologies. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(4), 440–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2017.1278020

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE.