Abstract

Education has the potential to change lives, however, sadly educational inequalities persist. Now, in the context of various global crises, is a timely moment to encourage people to act. In contemporary society we have witnessed major geo-political events with huge implications for social relations at local, national and global levels. Chief among these is the growing divide between rich and poor, political polarisation and the rise of far-right extremism, and the climate change crisis and associated environmental protests. In addition, the #MeToo movement has given a voice to those who have suffered sexual harassment or violence. And in 2020 the global pandemic (COVID-19) brought into sharp focus existing inequalities, highlighting that already disadvantaged groups – or rather groups living in disadvantaged circumstances – suffered the consequences of COVID-19 more greatly. The year 2020 also witnessed the largest and most widespread internationally Black Lives Matter protests in the history of the movement, following the murder of George Floyd.

Within this context, educational inequalities persist as “wicked problems” (Case & Huisman, Citation2016; Rittel & Webber, Citation1973). These are complex problems, with solutions dependent on how problems are framed, with different stakeholders holding different perspectives, which we might refer to as a multifaceted perspective of the “definition of the situation” (Rhoads & Gu, Citation2012). This means there are no easy solutions. However, whilst scholarship about “wicked problems” has tended towards positioning such problems as so complex they defy definition and solution, our view is more hopeful that progress can be made (Alford & Head, Citation2017). As Martin (Citation2019) writes, reflecting upon previous contributors to Educational Review, scholars “grapple sensitively with harsh realities, resistances and challenges, while keeping a hopeful view both of education’s potential and our belief in human educability” (p.114). In a world of increasing complexity, uncertainty and precarity and against the backdrop of a global economic and environmental crisis, political extremism, systemic racism and sexism, and the COVID-19 pandemic, long-standing and deep disparities in our education systems have been laid bare. Change is required.

This Special Issue (SI) of Educational Review focuses on educational inequalities in an age of globalisation and (super)diversity, exploring what we know and don’t know about inequality in education and why educational inequalities continue to exist and develop. This in turn necessitates a re-analysis of explanatory frameworks to develop new ways of approaching education’s “wicked problems”. This critical re-view addresses three main questions:

To what extent is our view of those well-established inequalities still applicable in the present juncture; for example, how do class, gender, disability, race and ethnicity continue to shape educational trajectories and experiences, and why?

What “new” educational inequalities are now here, and how do they relate to those that we know and think we largely understand?

What new approaches might tackle these persistent and new inequalities?

The call for papers was launched in April 2022. As editors, we were overwhelmed with the number of high-quality abstract submissions from scholars around the world (in total 133 abstracts). The SI contains 11 articles from academics based in Australia, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, the UK and USA. Except for two of the articles, which take a global view, the countries studied are those in which the authors are based, however, the implications for research, policy and practice are of international relevance. The specific “groups” in focus include: international students in higher education; university leaders; trainee teachers; classroom teachers; students in special education; migrant and segregated students. The SI includes original research articles, drawing upon the authors’ empirical data (five in total) and re-views of the field leading to the development of conceptual frameworks grounded by/in theory (six in total). The original research articles draw upon a range of methodological approaches (observation, interviews, policy analysis, surveys, student essays) and include co-production with end users and policy makers and innovative ways in which students might “speak up” for themselves (via multimedia diaries). The articles have been presented in alphabetical order by author.

Trends in the research

Educational inequalities constitute a classic subject for research, and researchers from many disciplines are active in what is a huge field of study with many strands. The sheer quantity of publications on the subject published every year is humbling and consequently it is not easy to identify meaningful trends. We suggest there are at least two trends in recent twenty-first-century history of the field that are worth noting here: increasing attention to intersectionality on the one hand and equity and justice on the other. More and more studies on educational inequality pay at least some attention to the intersection of race, ethnicity, class or socioeconomic status, gender, dis/ability, sexual orientation, language and other characteristics that form an integral part of a person’s identity. Crenshaw (Citation1989) coined the term, stating: “Intersectionality is a metaphor for understanding the ways that multiple forms of inequality or disadvantage sometimes compound themselves and create obstacles that often are not understood among conventional ways of thinking” (Crenshaw, Citation1989, p. 149). Educational inequality, historically, has been framed in terms of disadvantage and “deficit”, albeit with the best intentions. Increasingly, however, educational inequality is now being framed in terms of equity and justice, with an emphasis upon inequality not being an individual issue, but a societal one. Apart from that there is an ongoing discussion on the varying conceptualisations of equality. In turn, each framing has consequences for the type of policy approaches that are chosen. See the following figures.

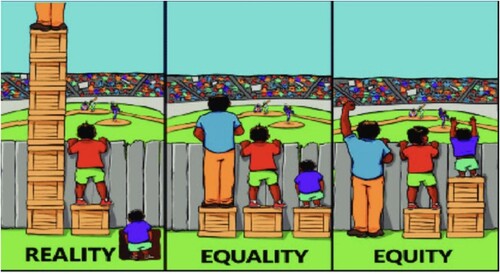

is metaphorically a good way to consider the distribution of resources. The image entitled “REALITY” draws our attention to the fact that people have different starting positions in life, both generally and when entering education, in particular. This is why equality of educational opportunities is not enough, as indicated in the image. Equity, on the other hand, is about recognising people’s different needs and understanding that people may need different resources and opportunities to bring about equity. The ideal image – as one of our reviewers of this introduction suggested – would be to have an image with no fence and equal access for all.

Figure 1. Distribution of resources: reality, equality, equity. Source: https://www.philippinesbasiceducation.us/2016/02/equality-equity-and-reality.html

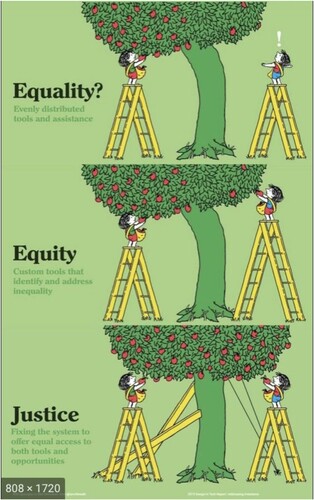

has some overlap with in showing that handing out equal tools evenly does not allow all children to reach the “apples on the tree”, and that customised tools and assistance that identify and address inequalities are necessary. also adds the perspective of justice; that is to offer access to both tools and opportunities (as the text in states), but also to allow for equality of outcomes in education and the flourishing of (the talents of) all students.

Figure 2. Equality, equity, justice. Source: https://onlinepublichealth.gwu.edu/resources/equity-vs-equality/

What the trends towards intersectionality and equity/justice have in common, is a critical attitude towards the status quo in education and society, where inequalities are often huge and growing, ranging from economic, social and political inequality to inequality in wellbeing, health and housing (Savage, Citation2021; Sayer, Citation2016). For instance, the Gini index shows the uneven and unequal distribution of income and wealth in the world, and Piketty (Citation2014) has shown that financial capital increases much faster than income from work (due to tax systems, among other things). Financial capital in turn translates into social, cultural and political capital, which helps to explain why regimes of educational inequalities are difficult to change and are generally reproduced (Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1977).

These trends are well represented in this Special Issue. Most authors work in (recent) critical traditions, e.g. Critical Race Theory in Education, Feminist Theory, Emancipatory Education, and Disability Justice. Many try to bring those traditions and the current discourse a step further by (re)imagining a way forward. For instance, by proposing new, multidimensional frameworks for analysis, developing integrated approaches, or intersectional, discursive, emotive and material lenses to imagine more just futures. Most of them also share a common motivation: social justice and emancipation for students at risk or marginalised. This critical attitude is also apparent when authors in the Special Issue question assumptions underlying discourses or policies. For example, the assumption that it is sufficient to mention the right to education in a policy document without putting measures in place that allow for effective implementation of that right; or the assumption that the medical model covers everything that is needed for equality in education for students with disabilities. Another case in point is the assumptions underlying the idea of meritocracy.

The term had a longer genealogy (Littler, Citation2018) and when Young introduced the term in Citation1958 to a broader public, he warned of the negative consequences, for example elite formation (as Aiston and Fitzgerald discuss in detail in their contribution to this SI). Sandel (Citation2020) argues that meritocracy is not a remedy for inequality. On the contrary, it is ultimately mainly used to legitimise educational inequality. People who are successful in education tend to think that their success is their own doing, and that people who are not successful are responsible for their fate and not deserving of support. That is what Sandel calls the tyranny of merit.

Theories and concepts

Critically, authors contributing to the Special Issue take a theory-driven approach to consider why educational inequalities persist, including explicitly connecting theory to practice. Some of the theories used are already mentioned above, such as intersectional theory, critical race theory and Bourdieu’s theory of reproduction of inequalities through different types of capital. Among the other theories used are: subversive pedagogy (Bernstein); systemic functional linguistics (Halliday); social-cultural theory (Vygotsky); decolonial pedagogy; theories on epistemic inequality and epistemic injustice; theory of complex systems; the capability approach (Sen and Nussbaum); queer theory; and Unterhalter’s three-fold perspective – equity from below, the middle and the top. The variety of concepts and theories that are used show that many strands in the field of research on educational inequality are represented in this Special Issue, which gives (generalist) readers an opportunity to get more acquainted with those theories and concepts, and learn more about their explanatory power and possibilities.

In the Handbook of Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education, Stevens and Dworkin (Citation2014) identified interrogating notions of (in)equality and ethnicity/race as one of the directions for future research. They called for a more critical approach to how researchers conceptualise and measure notions of “equality” and “equity”. Similarly, they stated that future research should adopt a more careful approach to the use of “ethnicity” and “race” as explanatory concepts (Stevens & Dworkin, Citation2014, pp. 629–30.) A decade later we can state that researchers of educational inequality have done a lot of reflection on (explanatory) concepts. The Special Issue shows this reflection is now not limited to equality and equity, but also involves social justice, and is not limited to race and ethnicity, but also involves gender and sexuality, socioeconomic status and more.

Many authors of this Special Issue use more than one theory or perspective, mainly because educational inequality is such a complex issue. Complex and often untamed, which means (1) our knowledge of causes and remedies is sometimes incomplete or contested, (2) there are many stakeholders involved that need to cooperate, and (3) they sometimes have different normative views on the subject. The first factor is an international one and we think the degree of uncertainty about causes and remedies regarding educational inequality do not result in an untamable issue. Waslander argues we know, for instance, that working with standards for learning helps, and that segregation between schools does not help (in general); that putting the “best” teachers before students most at risk helps; and leaving the distribution of (often scarce) teachers to the free market does not help (Waslander, Citation2020). We think the normative view or political ideology is the most important obstacle here. Key questions are whether one considers educational inequality an urgent issue that needs to be tackled; and how educational inequality is defined and framed. Education is a public issue that requires (public) investment and cooperation instead of competition and in the end is a public good and not a neoliberal (quasi) market (as e.g. Grace, Citation2002, and many others argued). Those key questions are ultimately political in nature. If key stakeholders agree on answers to those questions, however, cooperation is achievable and institutional complexity can be overcome. The formation of collective agency for equality in education might be helpful here, for instance in education labs or networked improvement communities.

So, to tackle the complex issue of educational inequality we need new approaches that allow us to strengthen the knowledge base, to facilitate and stimulate cooperation between stakeholders, and especially to address normative questions in a dialogue focused on the common good for all. That is what the authors of this Special Issue set out to do.

They know this will never be easy because combating educational inequalities is also about status, privilege and power – things people do not give up easily. Some scholars have therefore been pessimistic about the role of education. For instance, Bourdieu emphasised education’s role in the reproduction of inequality (Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1977). Eribon talks about “the verdict of society” that puts everyone in place in a social class, and he states that such a verdict is almost impossible to avoid, also thanks to the educational system (Eribon, Citation2013). Yet questioning the verdict is a way to appeal against it and assembling critical knowledge might help to change the situation. What Eribon knows for sure, is:

… that only a continually renewed theoretical analysis of the survival mechanisms … , coupled with the ineradicable will to change the world in the direction of greater social justice, will give us the opportunity to resist the various forms of oppressive violence. (Eribon, Citation2013/2023, p. 239)

Of course, educational inequality intersects with inequalities in other domains of society, and combating educational inequality is therefore connected to combating those other inequalities. As Bernstein noted, “education cannot compensate for society, but schools that aspire to be ‘incubators of democracy’ have a moral duty to try” (quoted in Reay, Citation2011, p. 2). Bernstein (Citation1970) was convinced education can and does make a difference, but only within certain limits. Those limits are set by the other inequalities in society, among other things, and since all inequalities in a democratic society can be addressed in democratic ways, schools have a role to play, as scholars from Dewey (Citation1916) to Eribon (Citation2013) have pointed out over the last more than hundred years.

It is not exactly clear at this point what Eribon and Bernstein might mean when they write about democratic politics and incubators of democracy, only that for them democracy includes (some form of) educational equality. When it comes to Dewey, it is crystal clear that for him democracy and education are fully interlocked: democracy is defined by the continuous education of individuals, and schools serve that purpose of democracy by helping develop democratic citizens (Dewey, Citation1916). In his view democracy was directly hindered by economic inequality and structural inequalities in the broader society that inevitably exercise a corrupting effect on the political debate. Such inequalities are undemocratic in themselves by denying individuals the opportunity to exercise control over their lives. Political democracy therefore needs to be supplemented with social and economic democracy (Dewey, Citation1927; summarised by Jackson, Citation2015). Addressing social inequality requires the “invention and projection of far-reaching social plans” according to Dewey (Citation1935), who attempted to create a radical political party in the 1930s to directly combat inequalities and the social and political power of wealth (Bordeau, Citation1971; Jackson, Citation2015). This was radical in the sense that root causes of inequality and other issues were addressed. The ideas were liberal and left wing in the political spectrum in the USA, but most of them would be characterised as social democratic and more mainstream in (Northern) Europe – somewhat like the ideas of Sanders (Citation2023) nowadays. We think the views of Dewey and his experimental approach to political, social, and economic problems are still relevant today, and can inspire answers to the questions raised by Bernstein and Eribon about democratic politics and education. For Dewey, education is the fundamental method of social progress and reform.

The alternative Sandel (Citation2020) develops to meritocracy might also offer some inspiration here. First, he rejects free-market liberalism and welfare state liberalism as alternatives, because they do not offer “an account of the common good sufficiently robust to counter the hubris and humiliation to which meritocracies are prone” (pp. 125–126). Thereafter he states that the democratic project requires “that citizens from different walks of life encounter one another in common places and public spaces”, for instance in schools (p. 227). The views of Eribon, Bernstein and Sandel also resonate with the intentions of most authors in this Special Issue, especially when they write about policies for change.

Content of the special issue

Combined, the articles offer a radical reply to established knowledge traditions and suggest new methods of working towards equal education for all. Not surprisingly, the focus is on marginalisation. Unsurprisingly, equitable curriculum access is a central concern. Hayes, Lomer and Taha reflect upon epistemic inequality within the context of higher education. To date, the decolonial literature has focused upon “indigenous students”, but what of the experiences of international students? A gap in decolonial praxis, compounded by a lack of reflexivity among university staff in relation to their own epistemological situatedness, means that international students are epistemically marginalised within national systems that heavily rely on international students. Relatedly, Harper and Parkin in this SI focus upon education and marginalisation and ask how does a classroom teacher address educational inequality with those students marginalised from the curriculum? Using the science curriculum as a case study, Harper and Parkin analyse the teaching and learning interactions between teachers, students and the curriculum, and more specifically the criticality of scientific language acquisition as fundamental to an inclusive curriculum.

Educational leaders have a fundamental role to play in combating inequality. Teachers as leaders, however, may not always be prepared to fulfil this role. Kasa, Brunila and Toivanen’s article focuses upon human rights education in the Finnish context – a country positioned globally as a success story in relation to equality and education, yet inequalities persist. Kasa et al. analyse the limited progress made in integrating equality and human education into teacher training programmes, resulting in teachers being “strategically” ignorant, ambivalent and “innocent”. Similarly, Weitkamper’s analysis of “authority” in the classroom and the link to inequality, draws our attention to the concept of teacher vulnerability. When vulnerable, a “doing of authority” becomes visible and a re-staging of inequalities is performed, as the vulnerable teacher assigns their students to well-rehearsed binaries, such as the “good” versus the “bad” student (who is degraded and at the same time vulnerable themselves). Aiston and Fitzgerald consider the privileged profiles of those leading the world’s most elite universities, querying trajectories of merit and asking is it right that the privileged lead the privileged? Arguing that elite universities are part of a closed hermetically sealed system of privilege (privileged leaders lead privileged students), meritocratic credentialism is positioned as the last acceptable bias.

Segregation in turn is analysed as a barrier to equality. Cruz, Firestone and Love consider how special education systems disproportionately harm students from minoritised groups, particularly students who are multiply marginalised. Linking back to the focus upon the curriculum, Cruz et al. highlight that these students are more likely to experience teacher-directed instruction, rather than having the opportunity to develop critical thinking and collaborative skills, thereby presenting an equity issue with life-altering implications. As discussed by Voulgarides, Etscheidt and Hernandez-Saca, the over-identification of ethnic minority students for special or compensatory education is a global issue, despite national legal protection and an international human rights framework. Key to understanding this over-identification is to consider how ableism and racism intersect. Whilst Cruz et al. and Voulgarides et al. bring into sharp focus the need to analyse how intersecting identities work to privilege some, whilst disadvantaging others, Boterman and Walraven consider how systems intersect to bring about inequality. Defining school segregation in the broadest sense, the entire educational system is defined as the separation of opportunities, again with life-altering implications. Given the complexity of the issue it is not therefore surprising that policies have had little success. Finally, Miller’s call to action is to make visible, through an intersectional lens, the experiences of disabled girls of colour. Dynamic layers of oppression in educational structures and processes are presented – once again – as having life altering implications.

And what of those students excluded from education? Gomez-Gonzalez, Tierno-Garcia and Girbes-Peco draw our attention to the experiences of Roma/Gitanos and Moroccan immigrants in Spain. As a group, they represent the highest rates of educational exclusion in the country. However, family education programmes, as a means by which to engage families in their children’s education, are championed. Relatedly, Blessed-Sayah and Griffiths focus upon equitable access for “illegal” migrant children in South Africa, a context in which migration is seen as a threat to national security and sovereignty. Here equality is problematised and equity is promoted as the approach to recognise difference.

Macro, meso and micro level

The articles consider the macro-level and/or the meso-level and/or the micro-level. At the macro-level, Hayes focuses upon the global international student market, within a micro-context to explore lived experience. Kasa reflects on the macro-level of Finland as a nation, the lack of structural change at the meso-level (i.e. university teacher training) and the micro-level (i.e. left to committed individuals to promote human rights and equality in the class). Cruz argues that critical inclusion cannot be achieved without larger systemic change, for example, legal infrastructures (macro-level); at the meso-level schools justify exclusion and reproduce inequalities; and at the micro-level the dynamic multiplicity of students’ identities are ignored. Relatedly, Voulgarides et al. showcase how educational law and policy sustain ableism (macro-level), which in turn then plays out at both the meso and micro-level. Blessed-Sayah also takes a critical lens to the macro-level: national policies contradicting each other, resulting in legal ambiguity, which prevents undocumented migrant children from accessing education. Boterman & Walraven focus on segregation as an issue of collective action, therefore they prioritise the macro-level, but also reflect upon the meso-level for policy implications. Meanwhile, Harper et al., Weitkamper, and Gomez et al. concentrate on the micro-level – that is what happens in the classroom and with parents to both reproduce and resist marginalisation. Finally, Aiston and Fitzgerald at the macro-level call for a rethink and reframing of how we approach equality, diversity and inclusion in higher leadership in elite universities, whilst Miller urges all stakeholders at the macro-level to take seriously the experiences and perspectives of disabled girls of colour.

Implications

We encouraged contributors to establish what we know about “what works, for whom, when, where and how” and to consider the crucial issue of knowledge transfer from research to policy and practice. How might we stop the “merry-go-round” of temporary projects, the vicious circle of “so much reform, so little change?” (Payne, Citation2009) and start working towards sustainable results collectively? The authors therefore set forth a series of implications for future research, policy and practice.

Implications for research are as follows:

Do more participative action research. For instance, classroom-based research in collaboration with teachers (Harper, et al.), especially focused on exploring interplay between inequalities, classroom authority and emotions in practice (Weitkamper).

Do more multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: combining relevant disciplines and connecting research evidence, professional knowledge and experiential knowledge (Boterman & Walraven).

Give special attention to the experiences and perspectives of target groups like disabled girls of color (Miller; Hayes, et al.).

Research fixed and singular conceptions of students that normalise exclusion (Cruz, et al.).

Examine systematically how leadership roles are acquired and by whom, and what values and attributes are required in a leader in an elite institution (Aiston and Fitzgerald).

Use classic and more recent critical theories as well as philosophical perspectives (Boterman and Walraven).

Build data-driven models using social complexity science (Boterman and Walraven).

Implications for policy are as follows:

Policymakers themselves need educating in this field so that the status quo is not simply reproduced (Kasa, et al.).

Policymakers must not oversimplify the problem, look for quick-fixes and think they only need to push one “button”; they need to understand that the complex issue asks for a combination of measures and for cooperation at different levels (especially the systemic level), in other words for pulling several strings at the same time (Boterman and Walraven).

The “labelling” of students as the means by which to allocate resources should be reconsidered (Cruz et al.).

Policymakers should engage in Critical Discourse Analysis to expose and deconstruct the ableism, racism and other “isms” embedded within legal frameworks (Voulgarides et al.).

Governing structures that give a voice to all educational stakeholders (Boterman and Walraven), including youth perspectives (Miller) need to be established.

Equity rather than equality must be the guiding principle for driving policy formation, with a human rights approach, to allow access to education for all (Blessed-Sayah).

Policymakers need to examine the ideological underpinnings of policies and grasp how multiple intersecting oppressions are perpetuated through policy (Miller).

Implications for practice are as follows:

Teachers need to reflect upon their positionality and how they may or may not contribute to the epistemic marginalisation of students in the classroom (Hayes et al.).

Teachers should be empowered to critically self-reflect, questioning dominant power relations and acknowledging responsibility individually and collectively in relation to equality and human rights (Kasa, et al.).

Subversive pedagogy for students at risk of marginalisation (Harper, et al.) and inclusive pedagogy (recognising neuro-variability), which renders learning accessible to all (Cruz et al.) needs to be adopted.

Teachers should undertake reflective practice around (re)producing inequalities (Weitkamper).

The voices of students and their families regarding what is working and what is not need to be heard and marginalised students (i.e. disabled girls of colour) should be represented in the curriculum.

A high expectations climate for all students needs to be set and parents engaged in their children’s education via Family Education (Gomez, et al.).

Look at all levels: macro (system, laws), meso (educational institutions) and micro (students, teachers, educational professionals).

Be aware of the intersectionality of cultural, linguistic, gendered and racial and ethnic disparities.

There is an “invisible wall” of historically formed power structures that explains the continuation of inequalities. Critical self-reflection is needed.

Educational inequality is not an individual but a systemic problem. It requires collective action, shared responsibilities, multi-stakeholder cooperation. Acknowledge that.

Solving complex and often untamed problems requires thinking differently: developing new perspectives and alternatives to meritocracy and competition.

In closing

Educational inequality is a complex and in part untamed issue, as we have repeatedly emphasised. There are no easy solutions – because if there were, they would have been implemented long ago. For many decades professionals from educational policy, practice and research have tried to tackle the issue and although progress has been made and there is a lot to learn from those experiences, one might get pessimistic because educational inequalities sadly persist. That is one reason why we wanted to explore relatively new approaches in this Special Issue, to shed some light on promising perspectives. Did we find sparkles of hope? Yes, along with realistic alternatives and corroborated recommendations. We were humbled by the quality and amount of abstracts, proud of the quality of the papers included in the Special Issue, and are therefore convinced that the Special Issue is a meaningful contribution to the ongoing discourse. But in the end, that is for the readers to decide.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Joep Bakker, Gemma Banks, Clive Hedges, Jane Martin, and Carl Parsons for their critical feedback on an earlier version of this introduction. We would also like to thank Jane Martin for her editorial support and Gemma Banks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alford, J., & Head, B. W. (2017). Wicked and less wicked problems: A typology and a contingency framework. Policy and Society, 36(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1361634

- Bernstein, B. (1970). Education cannot compensate for society. New Society, 38, 344–347.

- Bordeau, E. J. (1971). John Dewey’s ideas about the great depression. Journal of the History of Ideas, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/2708325

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. Sage Publications.

- Case, J. M., & Huisman, J. (2016). Researching higher education: International perspectives on theory, policy and practice. Routledge.

- Cohen, L. (1992). Anthem. On the album The Future.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167.

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. MacMillan.

- Dewey, J. (1927). The Public and Its Problems. Holt Publishers.

- Dewey, J. (1935). The future of liberalism. The Journal of Philosophy, 32(9), 225–230.

- Eribon, D. (2013). La Societé comme verdict. (Dutch translation 2023).

- Grace, G. (2002). Catholic Schools. Mission, Markets and Morality. Routledge.

- Jackson, J. (2015). Dividing deliberative and participatory democracy through John Dewey. Democratic Theory, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.3167/dt.2015.020105

- Littler, J. (2018). Against meritocracy: Culture, power and myths of mobility. Routledge.

- Martin, J. (2019). The past in the present. Educational Review, 71(2), 143–145.

- Payne, C. M. (2009). So much reform, so little change. Harvard Education Press.

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Belknap.

- Reay, D. (2011). Schooling for democracy: A common school and a common university? A response to “schooling for democracy”. Democracy and Education, 19(1), 1–4.

- Rhoads, R. A., & Gu, D. Y. (2012). A gendered point of view on the challenges of women academics in the people's republic of China. Higher Education, 63(6), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9474-3

- Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Sandel, M. J. (2020). The tyranny of merit. Allen Lane.

- Sanders, B. (2023). It’s OK to be angry about capitalism. Crown.

- Savage, M. (2021). The return of inequality. Harvard University Press.

- Sayer, A. (2016). Why we can’t afford the rich.

- Stevens, P. A. J., & Dworkin, A. G. (2014). Handbook of race and ethnic inequalities in education. Palgrave.

- Waslander, S. (2020). Ontembare problemen. De Nieuwe Meso, 7(1), 14–16.

- Young, M. (1958). The rise of meritocracy, 1970–2033. Thames & Hudson.