ABSTRACT

This paper reports on a study exploring the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on secondary school children's mental health and well-being in the North of England. It explores three research questions: to what extent has the Covid-19 pandemic affected secondary school children’s mental health and wellbeing in England? What did students value most for their mental health and wellbeing in a secondary school context during the Covid-19 pandemic? What are the implications for the post-pandemic future? A qualitative multi-method research design was used consisting of an online questionnaire survey (n = 605) and follow-up focus group interviews (n = 16). The findings of the study show that the pandemic and associated restrictions had a detrimental effect on the lives of a very large proportion of the young people in our study, with greater impact on girls than boys. From the analysis the resilience and ability of the participants to “bounce back” from the upheavals caused by the restrictions was apparent. However, for a significant minority the adverse impacts on their mental health and wellbeing continue to affect their lives. The idea of returning to “normal” following a period of crisis and turmoil such as the Covid-19 pandemic, emerges as an unhelpful concept because of the implied associated expectation of a smooth return to the routines prior to the pandemic crisis. This assumption is problematic as this study’s findings demonstrate. The “new” normal is experienced differently by students, especially girls, to what was “normal” experience before the pandemic and this has significant implications for schools.

Mental health is a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. Mental health is a basic human right. And it is crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development. (World Health Organization, Citation2022)

Young people’s wellbeing and mental health in the time of pandemic crisis

As the immediate crisis and response to the Covid-19 pandemic gives way to examination, analysis and attempts to construct a history of events and their meaning and implications for the future, much attention is focussed on clinical and medical issues and economic and social impact. Already the official inquiry into the pandemic and the UK responses to it have thrown up familiar political, social and economic dividing lines. Those responsible for post-2010 policies of austerity maintain the reduction in the public realm and attendant weakening of economic, health and social conditions in many communities had no adverse effect on our ability to weather the pandemic storm (see UK Covid-Citation19 Inquiry, Citation2023, former prime minister David Cameron’s witness statement) whilst those who suffered personal and family loss and were at the front line of public service offer powerful testimony otherwise (see, for example, UK Covid-Citation19 Inquiry, Citation2023, the opening statement of Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK and Northern Ireland).

In all the heat and noise about the impact on the economy, the health service, and the (mis)conduct of government, evidence emerges in the academic literature and a range of reports from voluntary agencies and think tanks about impacts on children and young people, in particular the effect on their mental health and wellbeing. For instance, the Commission on Young Lives as an independent commission launched in 2021 in the UK to develop proposals for a new national system to prevent crises in vulnerable young people and support them to succeed in life. In its “Hidden in Plain Sight” report, the Chair of the Commission on Young Lives stresses that:

The long-term effects of Covid and lockdowns on a generation of young people remain, in my view and the view of many others who work closely with children, greatly underestimated. We see an immediate future where there are even more problems like lack of readiness for school, speech and language development problems, mental health conditions, and increased poverty (Longfield, Citation2022, p. 5)

Before reviewing what this evidence suggests, it is worth setting some context for concerns about children and young people’s mental health. A National Health Service (NHS) study in the UK (Newlove-Delgado et al., Citation2022) shows that before the Covid-19 pandemic, increasing numbers of children and young people were suffering from poor mental health and wellbeing. Commentators and researchers, taking up Foucault’s analysis (Mills, Citation2003; Foucault, Citation2020), suggest that poor mental health and mental illness exhibited by children and young people is a function of social conditions; individual difficulties arise primarily from dissonance and disconnect between children’s needs and the social, academic and organisational requirements imposed on them by institutions (most notably schools) and social pressure and expectations of responsibilisation imposed by individualistic and market-driven “normative parameters … typically provided by a drive for enhanced efficiency” (Clarke et al., Citation2021, p. 192). Layard and Dunn (Citation2009) highlight the clear relation between deteriorating material conditions and inequalities, which have been increasing over the past decade (Marmot et al., Citation2020), and parental and family stress and breakdown. This increase in poverty and family stress has a clear association and correlation with children and young people’s poor and declining mental health and wellbeing, as Taylor-Robinson et al. (Citation2023, p. 1) conclude:

Child poverty is a common, preventable exposure that drives high levels of health and social care use over the lifecourse … These exposures lead to large negative impacts on child physical, mental, cognitive and behavioural outcomes including, for example explaining about half of the burden of mental health problems in adolescence.

For our review of literature to establish the issues and themes in the realm of children and young people’s mental health post Covid-19 pandemic we looked for material published after 2020 using the search terms “Covid-19”, “children and young people” and “mental health”. We used the databases Web of Science and Google Scholar to identify academic, peer reviewed articles and a more general search using Google to identify so called “grey literature”, in this case a range of reports from third sector organisations, government agencies and “think tanks”. The literature reviewed for this article is clear that a consequence of the pandemic and the society-wide responses to it has been an increase in poor mental health and wellbeing amongst children and young people (notwithstanding some studies which report that for some children, school closure and lockdown restrictions have had a beneficial impact on their state of mind). The following more detailed themes emerge from our review of this literature.

Some studies (e.g. Lockyer et al., Citation2022; Winter & Lavis, Citation2022) identify a strong sense of lost or diminished opportunities for qualification and transition to work or further/higher education. There was also a sense of denial of participation in important social and educational events that marked a rite of passage (e.g. the transition from primary to secondary school, formal leaving secondary school events) as well as the theme of lost learning more familiar from media discourse about the effect of the pandemic on young people. The question of denial of young people’s voice and rights and lack of any engagement or consultation with them by government or other authorities about the educational and social restrictions imposed also emerges (Lundy et al., Citation2021).

Many studies, using a variety of methodologies (e.g. interviews with children and young people and adults, online surveys, analysis of social media posts), report increased anxiety, worry, distress, low mood and depression. (e.g. Lawrance et al., Citation2022; Maynard et al., Citation2022; McKinlay et al., Citation2022; Winter & Lavis, Citation2022; Lockyer et al., Citation2022). In her review of literature on Covid-19 and mental health, Spiteri (Citation2021) highlights the explicit linkage between restrictions imposed to control the pandemic and negative effects on young people’s mental health. Widnall et al. (Citation2022) stress the importance of the young person’s context in determining the level of distress and deterioration in mental wellbeing, particularly in relation to social and family networks and the structure of activity and support provided by schools during lockdown. Soneson et al. (Citation2023) report that improved relationships with friends and family, less loneliness and exclusion, and reduced bullying contributed to a third of their sample reporting feeling happier during lockdown, whilst Widnall et al. (Citation2022) suggest these might be protective factors in maintaining mental health during periods of school closure. Schoon and Henseke (Citation2022) discuss the importance of socio-economic disadvantage in contributing to young people’s poor mental health. This factor, in the form of parental socio-economic hardship generated by the economic upheaval of the pandemic is explicitly cited as contributing to children and young people’s poor mental health by Cattan et al. (Citation2023). Whilst socio-economic disadvantage and negative family experience are correlated with increased mental health and wellbeing difficulties, some studies also suggest that the experience of pandemic restrictions contributed to poorer such outcomes for young people irrespective of background and context (Lockyer et al., Citation2022; Maynard et al., Citation2022).

Some studies indicate that for some young people their mental health and wellbeing improved during the lockdown restrictions. Soneson et al. (Citation2023) indicate that one third of their sample of 16,000 young people from the 2020 OxWell survey reported improved mental wellbeing during the first UK lockdown. The study suggests that this may be correlated with improved relationships with friends and family, less loneliness and exclusion, reduced bullying, and better management of school tasks reported by the young people concerned. Other studies suggest that where such improved mental health during periods of school closure is reported this may be as a result of the removal of prior stressors associated with school (e.g. peer pressure, bullying, authoritarian discipline, testing and assessment regimes) (Winter & Lavis, Citation2022).

Studies examined suggest two broad sets of factors which contribute to supporting young people’s mental health and wellbeing: social bonds, friendships and family relationships; and socio-economic status and context. There is also some mention of the role played by schools and the type and quality of support they provided during periods of school closure. The role of family, friends and social bonds, appears both as a mechanism to cope with the isolation and deprivations of lockdown and as a protective factor against mental health difficulties. Some studies suggest that relatively advantaged children were affected more substantially by being cut off from family and friends and the weakening of social bonds. For some children (characterised as more likely to suffer relative disadvantage) for whom school-related concerns such as bullying and harsh disciplinary regimes were a source of stress and mental health pressures, school closure was a welcome respite (Maynard et al., Citation2022). Studies considered for this review did not specifically highlight a gendered aspect in the effects reported but other studies, not focused solely on young people, (e.g. Carli, Citation2020; Rubery & Tavora, Citation2021) indicate the greater impact of the pandemic and economic and social policy responses on women and girls.

The study

To gain an understanding of young people’s wellbeing it is essential to access the views of young people themselves (Children’s Society, Citation2022) which have so far not been given prominence in the public debate. This inquiry drew on the views of young people about the development of factors conducive to their wellbeing and mental health in school and the sorts of factors that enable this. The research is particularly important and timely following the Covid-19 pandemic and the heightened awareness of the need to support young people’s wellbeing in recovery from its impacts (Department for Education, Citation2022). The engagement of children and young people in the development of policy responses in this area and planning for future such emergencies is vital (Academy of Medical Sciences, Citation2024).

A qualitative multi-method research design was used consisting of an online questionnaire survey and follow-up focus group interviews. The research took place in three secondary schools in one local authority area in England. The three schools were all state funded secondary comprehensives located in urban areas and serving socio-economically mixed catchments. Two of these schools were rated as “outstanding” in their latest inspections by The Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted), and one was rated as “good”. At the time of the study in two of the three schools the proportion of students eligible for Free School Meals was above the average for the local authority (LA) area but in all three below the average for English mainstream secondary schools. In addition, in all three schools the proportion of pupils whose first language was not English was below the national average in mainstream secondary schools in England.

Due to shared interests and concerns about young people’s mental health and wellbeing, initial contact was made with the LA inclusion adviser with whom the research and its potential value for schools was discussed. The initial discussion with schools took place at a routine meeting between the LA adviser and school senior leaders and volunteers were sought. The research team subsequently contacted the three schools via letters of invitation explaining the nature of the research and meetings to discuss arrangements for the research in each setting. Visits were made by the researchers to responding schools to discuss and explain the nature of the research. Due to the ages of the intended participants, parental or carer consent was also obtained. The three participating schools sent out the research information sheets to all Year 9 and Year 10 students’ parents via the schools’ online communication channels with parents. Following the LA’s advice, parents and carers were offered the opportunity to decide whether they would like their children to participate in the study. It was made clear that without parental consent, participation in the study was not possible. Participating schools were provided with a link to the survey and were asked to allow their Year 9 and Year 10 students aged between 14 and 15 years who wished to participate to complete it during form periods. In the survey, participants were asked to respond to the questions on a 3-point Likert scale. Space was also provided with each question for an optional free text response.

605 students responded to the online survey and 16 students took part in the follow-up focus group interviews. Following the online survey, participants were invited to take part in a follow-up focus group interview by informing their school tutors. The participating schools as the gatekeepers helped recruit these 16 students for the focus group interviews. The purpose of the focus group interviews was to further investigate their responses to the earlier survey. The focus group interviews also enabled researchers to explore unanticipated responses and obtain nuanced answers when the initial response was too general or brief.

During the focus group interview process, the researchers were critically aware of the extent to which interviewers can impose their own categories on respondents (Silverman, Citation2010, p. 245). To address this issue, in the focus group interviews, the researchers used a semi-structured format of prepared questions but with scope and flexibility to respond to participants’ ideas and comments through additional follow-up questions as appropriate (Savin-Baden & Howell Major, Citation2013). With semi-structured interviewing, the open-ended nature of the question defines the topic under investigation, but also provides opportunities for the interviewer and interviewee to discuss some topics in more detail. In a semi-structured interview, the interviewer also had the freedom to probe the interviewee to elaborate on the original response or to follow a line of inquiry introduced by the interviewee. During the interview process, interviewers refrained from influencing participants in any way and maintained a neutral manner with sensitivity and respect. All focus group interviews took place in person at the participating school premises. For child safeguarding, researchers conducting the focus group interviews had an enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check.

Ethical approval for the study was considered and granted by a university research committee. As part of the anonymous questionnaire survey, participants were provided with an information sheet and given the option to withdraw their consent after the data collection. This was achieved by asking participants to give a four-digit code in the survey. If a participant wished to withdraw from the study, the four-digit code would be used to locate and remove their response. All data were anonymised and securely stored for the duration of the research project. In addition, at the end of the online survey, all participants were reminded that the survey was anonymous and that the researchers did not have any way of identifying participants and their answers. If taking part in the survey had raised any concerns or worries, participants were asked to seek help and support from relevant school staff. A web link to a local children’s mental health and wellbeing support service was also provided.

The qualitative narrative data for this study were analysed inductively using a thematic approach with a particular concern to voice the students’ perspectives in their response to the research questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). For the data analysis, the following steps were taken – immersion, reflecting, taking apart data, recombining data, relating and locating one’s data, reflecting back and presenting the data (Wellington, Citation2015). In essence, this was a three-stage process: firstly reading and re-reading of survey data (numerical scores and free text responses) and focus group interview transcripts to achieve familiarisation and immersion in the data and produce notes and observations of these data as a prelude to establishing patterns and themes; secondly, a more analytical coding to generate the building blocks for construction of themes, that is the meanings that could be built; and thirdly, examining the codes and coded data to construct provisional themes. All the authors were actively involved in the data analysis process – immersion of data, the analytical and interpretative process, and the writing of the analysis. Each of the authors conducted the analysis individually first, and then shared their interpretations of the data with each other before agreeing on the key themes as shown in Appendix 1.

Findings

In this section, statistics and their visual representations in the form of figures are used to illustrate patterns, relationships, or comparisons within the qualitative data. The quantitative data were analysed at a whole cohort level and individual school responses were not disaggregated. An analysis of the quantitative data was carried out using the analysis function in the online survey tool, shown as visual representations of the data. These visual representations provide a clear and concise overview of the findings. In this way, the use of statistics and their visual representations complements the qualitative data analysis.

Struggles during and after the Covid-19 pandemic

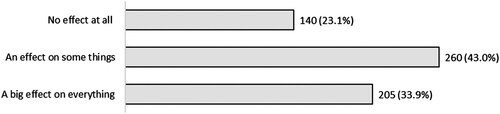

In the study, a large majority of participants (over 75%) reported that the Covid-19 pandemic had affected their daily routine and school life during the lockdown between March 2020 and December 2020 (see ). Consequently, the impact of their daily routine and school life affected these secondary school students’ mental health and wellbeing. Whilst the same proportion of boys and girls reported some effect on daily life (43%), a much higher proportion of girls (41%) reported a big effect than boys (28%). Overall 85% of girls reported an effect on their daily lives against 71% of boys.

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic was evidenced by participants’ strong feelings of learning loss, isolation due to remote learning, and challenges due to individual personal or family circumstances. During the lockdown, the majority of participants were in the final year of primary school education. The majority of them had to study at home unless their parents were key workers whose work was critical to the Covid-19 response, including those who work in health and social care and in other sectors identified by the UK government.

Some students were struggling with the sudden change of the daily routine and new ways of schooling. One participant remarked in the survey – “I find not having a repeating routine is hard and I struggle to adapt to the sudden change” (Participant S2730, Year 9 female). The sudden change to online learning also led to other challenges.

I barely go out during lock down and this caused me to be more easily irritated than usual. I also missed out on a lot of learning as everything was done online. I also felt lonely and isolated. I didn't have any friends at the time and barely have any interactions outside of my family. (Participant S7047, Year 10 female)

Participants were also disappointed by not having the opportunity to conclude their final year of primary school education properly. For example, they did not have the opportunity for the residential trip and the primary school leaving ceremony. In some ways, participants felt that they did not finish primary school in the normal way and neither did they start secondary school in the normal way.

School was at home and I lost a lot of education. I also became less confident with socialising and starting secondary in Covid and bubbles was very scary. I had to be with people in my class and the masks made everything 10 times harder. I missed out on my SAT's and all the rewards. I left primary after not doing the reward show talent show, breakfast pizza party, ice cream van party. (Participant S4457, Year 9 female)

In the above narrative, “bubbles” refers to a UK Covid policy between September 2020 and July 2021 where people living in small, non-overlapping, groups of households were permitted to come into contact with one another. A “bubbles” system was also operated in school settings during the Covid-19 pandemic, but with different parameters. Participants’ individual circumstances also compounded the impact of Covid-19 pandemic. For example, some participants’ parents were critical workers or on the vulnerable persons list.

I had to stay at home all day every day and wasn't allowed to go out at all because my mum was on the vulnerable persons list. At the end of year 6, I was allowed to go back into school but had to stay at least two metres away from everyone else. (Participant S1708, Year 9 female)

Working from home, covid tests everyday as my parents are key workers, tired all the time, and paranoid. (Participant S1980, Year 10 female)

In the interview, participants also reflected on how their family circumstances might have an impact on their learning experiences and wellbeing. These circumstances include whether they had some family members infected with Covid, whether their parents were single parents, whether their parents’ employment during the lockdown was secure, and even whether they have a garden at home. One participant remarked:

I think we were quite lucky because I had quite a big back garden. So that was like I spent a lot of my time outside, but I know people who are in apartments or housing that don't have a garden. It's quite hard just being inside, like and only having like one walk. (Participant G3000, Year 9 female)

The effect was mainly associated with the nervousness and fear when participants returned to in-person schooling from January 2022.

I mean, I got, I started, I got really bad depression after. Like it was really bad and I couldn't leave anywhere. And that was because of Covid because I got really anxious about leaving the house. I was like, what if someone gives me Covid? What if I've got it and I'm giving it to someone and then it was just like the pressure it gave me like really bad depression, anxiety. And I couldn't, I didn't go to school for, like, a month. Because I was just scared and worried about something like that happening again. (Participant G1010, Year 9 female)

In the interview, one participant shared her experience of returning to in-person schooling.

When that happened to me, I got so anxious that, like, I couldn't go to school because I get these panics. So if I get it and then it took like a while, but I got help because my form tutor was like calling me every day to, like, try and get me to go to school. (Participant G2002, Year 9 female)

Friendships and the Covid-19 pandemic

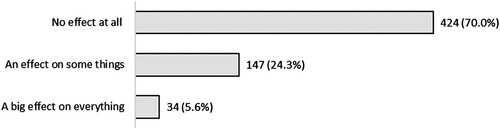

This study also found that the Covid-19 pandemic affected participants’ friendship at school. 43% of participants reported such an impact (see ). The gender differences in this effect are marked: over half of girls (54%) reported an impact, against a third of boys (34%).

Some participants reported that, during the pandemic lockdown period, they became closer to their friends.

I became a lot closer with my friends, since we'd call frequently and text each other to see how we were doing. (Participant S2717, Year 9 female)

Due to the pandemic, participants also recognised the importance of friendship and appreciated it more.

I think it makes you appreciate like your friends more because if they like, just imagining if they weren't there, just like pretending you're back in Covid and just sat at home doing nothing, then just makes you realise how much they're there for you and just and go, you should go places with them and stuff. (Participant G1000, Year 9 male)

I found it hard to keep in contact with my friends without being able to see them. (Participant S2247, Year 9 female)

I became distant with some of my friends because we weren't able to speak to each other because they lived too far away. (Participant S7481, Year 9 male)

I couldn't see my friends from school. Covid was when I was in Year 6 so I couldn't see my friends before we left primary school. Some of my friends didn't have phones so I couldn't text them. (Participant S8104, Year 9 female)

Resilience and coping strategies

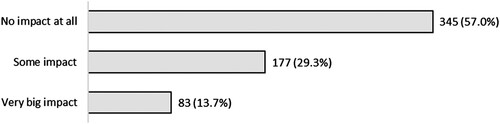

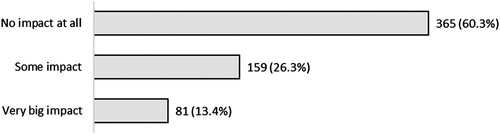

In this study, participants were specifically asked if Covid and related events had an impact on their mental health and wellbeing. As shown in below, almost 40% of the participants responded that there was some or a very big impact. Again, gender differences are marked. More than half of girls reported an impact (55%) against a quarter of boys (25%). A fifth of girls reported a very big impact (21%) against 5% of boys.

Figure 4. Have Covid and related events (lockdown, school closures, online learning etc.) had an impact on your mental health and wellbeing in any way?

The data show that the main causes of the impact included the isolation during the Covid lockdown periods, changes to the life routines, anxiety and experiences of Covid infections.

Due to Covid restrictions during the lockdown periods in England, participants had to study online at home.

It was very hard not having a normal routine for so long and I struggled not seeing any friends and when things went back to normal I struggled in social skills because I had not talked to other people for so long. (Participant S8097, Year 9 female)

Participants’ mental health and wellbeing was also affected by the consistent concerns and fear of Covid infection for themselves or their loved ones.

I was worried at the start about whether the people I loved would be hurt by the virus, and my dad was a paramedic during the lockdown – and he still is today – and I was always concerned if this mystery virus would mean I would never see him again. (Participant S1751, Year 9 male)

Some participants stated that they struggled with anxiety and depression and they had to seek professional help. The impact of Covid on their mental health worsened when participants already had other learning difficulties.

I struggle with depression and anxiety. I am also now under assessment with autism which I have never struggled with until now. (Participant S8097, Year 9 female)

For other participants, online learning from home had not only created isolation but also blurred the boundaries between school and home life. Consequently, it had an impact on participants’ mental health and wellbeing. Changes and disruptions to sleep patterns were also raised in a number of responses. This could result in a loss of motivation, no time perception, and an inability to articulate thoughts and feelings.

I started to feel lonely and would get upset when I did not understand the work and had nobody to help me. I also missed the separation between school and home. (Participant S2029, Year 9 gender designation as “other”)

I felt lonely and I was so bored having ADHD made this much worse. (Participant S3111, Year 10 male)

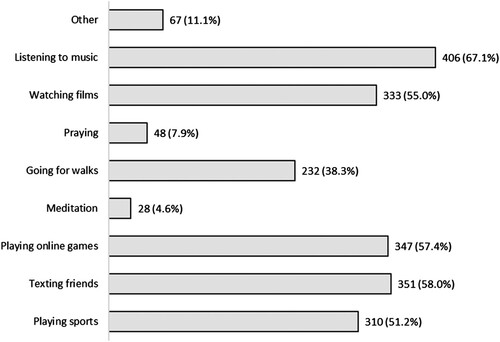

At the same time, young people who participated in the study had also shown great resilience as 60% of them stated that Covid had little or no impact on their mental health and wellbeing. As shown in below, participants adopted various strategies to cope with the challenges caused by Covid.

Many participants indicated that playing sports, texting friends, watching films, playing online games, and listening to music were the top choices. In this study, participants also indicated that having a pet and reading also helped them to cope during the Covid lockdowns.

Spending time on social media sites or apps was also another coping strategy adopted by many participants in this study. However, some participants recognised the potential downside of this strategy.

Being online a lot more during Covid definitely affected me both positively and negatively. Social media was a fun way to spend your time when at home and not able to go out. However, spending so much time when I was younger has definitely made me somewhat addicted. (Participant S8065, Year 9 female)

In this study, participants also indicated that pursuing their hobbies during the lockdowns also helped with their general wellbeing, so did spending time with their family members such as siblings.

Support received from schools and others

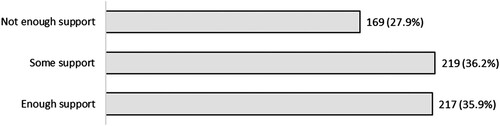

This study has found that a large proportion of participants had received support from their schools during the Covid pandemic. As shown in below, over 70% of respondents to the survey indicated that they had received some or enough support from their schools. At the same time, 27% of respondents stated that there was not enough support for them during the pandemic (see ). Fewer girls felt that there was enough support from schools (64%) than boys (79%).

During the Covid-19 pandemic, schools played an important role in maintaining children’s education by moving classrooms online due to the lockdowns. Online and distance learning was not ideal for many children. However, respondents appreciated that, given the circumstances, schools had done everything that could have been asked of them. In order to facilitate online learning, many schools had loaned IT equipment to children such as laptop computers and tablet devices. Some participants reflected on their experiences of online learning.

Having online lessons in lockdown was pretty good as they helped me to feel supported in my learning and the clubs that then opened after lockdown really helped me a lot. (Participant S1725, Year 9 gender designation as “other”)

My school had easy access to online learning and Google classroom made it easy to understand lessons and communicate with teachers. (Participant S1708, Year 9 female)

During online learning rather than just setting us work and letting us do it, teachers actually made live lessons making it as much like a classroom as possible. (Participant S4622, Year 9 male)

School teachers also played an important role in providing support to children for their mental health during the pandemic.

My mental health gets better and then gets worse for about a week and then things start to get better and it repeats over and over again until I can't take it anymore and start to self-harm again. I get upset most days because I don't know what to do in lessons and I'm too scared to ask for help. The only way I managed to tell school about my self-harm was by getting one of my friends to get a teacher to talk to me so I could tell her about it and then she helped me tell the deputy head and then we told my parents to get support. (Participant S1722, Year 9 gender designation as “other”)

With regard to operationalising the researchers’ ethics of safeguarding, the survey participants were reminded that the researchers had no means of identifying individuals. In the case of the kind of concerns indicated in the above quote, participants were advised to use the school’s safeguarding and support procedures. In this case it would appear that these were sufficiently robust to deal with the voluntary disclosure of this participant’s self-harm. Also, it appears that Participant S1722 had already sought help from the school in relation to the specific issue.

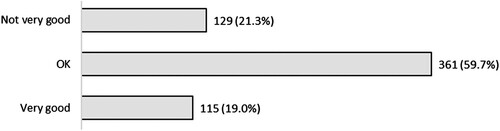

As shown in below, the majority of research participants (80%) perceived the support they received from school was good or very good. 21% of respondents suggested the support they received was not very good and schools perhaps could have done more. There was little gender difference in this reported view (girls 78% OK or better against 81% of boys).

Participants’ dissatisfaction was mainly related to the quality of the provision due to Covid restrictions at school as one student has pointed out.

At my school we went, for the start of it, we went in like little bubbles and it was just a normal classroom for everything. And then eventually when we had to go to school we didn't do zooms or anything. They just gave us lessons but it was optional. And they weren't really that educational. It would be stuff like bird watching or like activities like you'll be like skip or like take a walk or like how many tree cones can you find stuff. (Participant G3000, Year 9 female)

In addition, some participants perceived a better quality of education was offered to those children who had key worker parents and had the opportunity to attend school in person during lockdowns compared with the majority of children who had to study online and at home.

In relation to students’ mental health and wellbeing, participants suggested that schools may need to do more to ensure every child feels supported.

The school could do more mental health checks, say once a month or so to make sure the kids are actually okay instead of lying because they don't want anyone to know how they actually feel. (Participant 1722, Year 9 gender designation as “other”)

Discussion: the implications for the post-pandemic future

Analysis of our survey and interview data, which probed aspects of young people’s daily lives during and post-pandemic, evidenced the challenges experienced by young people relating to learning in the pandemic era. This era was characterised by “lockdown” periods which involved the prohibition of social activities and association, the closure of schools and the pivot to remote home-learning. Young people told us about the challenges they experienced related to isolation and denial of opportunities, compounded by anxieties provoked by the sudden and significant change to social life, learning modes and routines. For example, in-person social activities and association were banned during “lockdown” periods; many participants appeared to appreciate virtual contact as an alternative means of keeping in touch with their friends.

The analysis also evidenced the social and emotional impacts of a number of other factors including anxieties about family members’ employment security, health and circumstances at home during the pandemic on young people’s mental health. Significantly, transition back to in-person schooling brought its own challenges. It is concerning that Covid-related events had impacts for over 70% of the young people in our study and 20% reported continuing worries about the effect of these events on their lives. A higher proportion of girls reported continuing worries (29%) than boys (12%). The analysis suggests that there are lessons for schools, local and central government to learn about young people’s agency and support for mental health in the post-pandemic future from these young people’s accounts. The approximately 30% reporting continuing adverse effects may need a different kind of support and appropriate differentiation in the design of post-pandemic provision. One particular message that emerges from this study is that in the return to in-person schooling, the dominant emphasis on “catching-up” to make good the learning loss, appears to have been too restricted and narrow and in need of an accompanying narrative concerning the restoration and regeneration of social bonds that lie at the heart of schools as communities. Arguably, such a narrow focus on learning loss is fuelled by the relentless pressures of the current performativity culture which Ball (Citation2017, pp. 57–58) explains as “a regime of accountability that employs judgements, comparisons and displays as means of control, attrition and change. The performances of individual subjects or organisations serve as measures of productivity or output, or displays of ‘quality’, or ‘moments’ of promotion or inspection”. In performativity cultures, people “are valued for their productivity alone” (Ball & Olmedo, Citation2023, p. 136) and “results are prioritised over processes, numbers over experiences, procedures over ideas, productivity over creativity” (p. 137). According to Ball (Citation2003, p. 224) “performance has no room for caring” and we argue that the subjects created by cultures of performativity are governed in ways which reduce and constrain the space for concern about and consideration of the wider wellbeing and social bonds and relationships of the subject. Our findings indicate that there is a need for such spaces to be created and nurtured within any programme to support students post-pandemic. The argument advanced in this paper relates to how the technologies of neoliberalism are manifest in education, responsibilisation of individuals and in this policy climate, the erosion of notions of the common good. As Nixon (Citation2012, p. 16) puts it “The public good is not an abstraction, but the actuality of people working together for their own and others’ good”.

The idea of return to normality with the reopening of schools and transition back to in-person teaching with an expectation of a seamless return to normal routines and patterns of behaviour can be framed in Foucauldian thinking about the operation of “normalisation”:

Normalization, the institutionalization of the norm, of what counts as normal, indicates the pervasive standards that structure and define social meaning (Feder, Citation2011, p. 62)

Arguably, failure to slot back into the new “normal” routines as expected therefore suggests the behaviour to be “abnormal” and therefore contributing to reinforcement of the negative impacts of the pandemic. Hoffman (Citation2011, p. 32) notes how Foucault

depicts the norm as a standard of behaviour that allows for the measurement of forms of behaviour as “normal” or “abnormal”. In his words, “the norm introduces, as a useful imperative and as a result of measurement, all the shading of individual differences”.

This research was carried out in the summer term 2023 and the analysis evidences the legacy of the pandemic era in terms of continuing mental health difficulties for some young people, including those with pre-existing mental health issues prior to the pandemic. Whilst researchers had no knowledge about such conditions, in the survey responses, some participants disclosed that they had mental health issues and the Covid-19 pandemic had simply exacerbated their struggles. Findings from this study can be drawn on by institutions and government at local and national levels to inform future thinking about interventions which might have a positive or beneficial impact on young people’s mental health during and following a time of crisis, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. The study reaffirms the continuing importance of listening to young people’s perspectives and especially so in planning education provision during and following periods of crisis and significant disruption. Our purposes for this study stem from a belief that young people's voice and agency and knowledge about their experiences need to be valued and prioritised when we support their mental health and wellbeing needs. Kellett (Citation2005) has reminded us that young people need to be ‘acknowledged as experts on their own lives’ (p. 2). The recent Academy of Medical Sciences (Citation2024) report on child health also stresses the importance of child voice in health policy development.

Our research also indicates that the pandemic and associated restrictions had a detrimental effect on the mental health and wellbeing of a very large proportion of young people in our study, with greater impact on girls than boys. The analysis shows that the young people involved have demonstrated resilience and the ability to “bounce back” following the upheavals caused by the restrictions, but that there is a significant minority of young people for whom the adverse impacts on mental health and wellbeing continue to affect their lives. These continuing adverse effects are more marked amongst girls than boys. Our study also suggests that young people were deprived of freedoms, opportunities and significant life events which may affect their possibilities and future life trajectories. There was also a denial of agency in that profound changes with lasting effects were imposed on young people without any opportunities for engagement or involvement in such important decisions.

In the post-pandemic future, the “new normal is no longer normal”, as one of our respondents put it, and is likely to be marked by increased frequency of crises, global, national and local, embracing health, environmental, civic and infrastructure disruptions. In such a “new normal” our research suggests a number of areas to which educators and policy makers might attend. Firstly, a reinvigoration of children and young people's voice and engagement in the planning of provision and a reassertion of its importance in constructing a system of schooling that excites and enthuses young people and has a genuine future orientation with democratic practice at its core. Some have highlighted (Longfield, Citation2022 and Lundy et al., Citation2021) that attempts at even the most basic governmental communication with young people about the pandemic restrictions (most notably school closures) were lacking. The government (national and local) response to such future emergencies might be improved and enhanced by understanding young people’s experience of pandemic restrictions through their full and proper engagement in the processes of review of what happened during the Covid-19 pandemic, and using this knowledge and insight to inform future planning of services and provision. This might be further developed by creating opportunities for young people’s involvement in planning for future crisis situations at governmental and institutional levels.

Secondly, our study suggests there is a strong need to give more emphasis to maintaining social bonds of family and friendships during and in the aftermath of emergencies such as the pandemic. These factors emerge as of great importance to young people who feel their loss and restriction acutely. From our work we would suggest that such social bonds are a strong protective factor against mental health difficulties, both in preventing them from emerging and acting as mitigation where they do. This is particularly so in the return to education and the reopening of schools, when we suggest more time and emphasis might be devoted to nurturing and rebuilding social bonds. Arguably therefore “catch up” programmes and funding require a balanced focus across a range of domains which address the development of young people’s capabilities to manage such stresses and pressures.

Thirdly, we suggest that the experience of the pandemic and associated restrictions throws the question of the deterioration of young people’s mental health into sharper and more urgent focus. On the basis of this study, two points arise. One is the need for a properly funded and consistent level of early intervention support and help for young people with mental health difficulties. Our experience is that schools are providing this in the absence of other services which have been reduced or removed as part of the government-imposed austerity programme of the last 10 years. Our evidence suggests that this response by schools and the support provided was welcomed and appreciated by young people. Arguably, at both local and national levels it lacks a consistent approach, does not always ensure clear links and referral mechanisms to other services and is subject to increasingly stringent resource constraints, leaving individual schools finding the funding (ADCS, Citation2024). A coherent programme of support based on schools needs to address these issues in its design and execution. In addition, we suggest there needs to be a thorough and honest examination of the causes of increasing mental health difficulties, particularly in relation to the pressures and expectations placed on young people by the current testing, assessment and discipline regimes in schools. We suggest that such regimes are inimical to processes of engagement, democratic practice and participation which are at the heart of a schooling system that supports and encourages human flourishing.

Final thoughts

Whilst the role and value of engaging student voices in decision-making on matters impacting on their lives is generally well acknowledged, this study suggests that denial of opportunities for this in times of crisis, may compound the challenges experienced by young people and reinforce their loss of agency. The idea of returning to “normal” following a period of crisis and turmoil such as the Covid-19 pandemic, emerges as an unhelpful concept because of the implied associated expectation of a return to the routines prior to the pandemic crisis. This assumption is problematic as findings from this study demonstrate. The “new” normal is experienced differently by students, and especially girls, to what was “normal” experience before the pandemic and this has significant implications for schools. This adverse gendered impact reflects findings in wider population studies of the effects of the pandemic and associated policy responses. Being unable to slot back into the “new” normal may downplay the difficulties and impact experienced by young people and isolate and stigmatise by suggesting atypical and irregular behaviour, thus potentially further compounding mental health difficulties and undermining wellbeing. Slotting into the “new” normal has not been helped by the apparent disconnect between young people’s mental health and wellbeing needs, and the performative pressures for schools to demonstrate academic outcomes. The benefits for young people’s mental health of an equal restoration of relational ties with friendship groups to reinstate the bonds at the heart of schools as communities and the provision of a broad curriculum alongside the dominant learning “catch-up” narrative in the post-pandemic era emerges as a key lesson from the study.

Lastly, we acknowledge some potential limitations of this study. For example, due to the nature of qualitative research, generalisability needs to be made cautiously with acknowledgment of the ways in which the researchers, the research design, the relatively small sample size (two year groups in three English schools), and the context shaped the findings. In addition, we need to recognise that the idea of the “new normal” could be necessarily temporary, and will inevitably become the “old normal” supplanted by a new “new normal” at some stage in the future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge that this study was funded by York St John University via its Quality Research (QR) funding. A research briefing paper based on the main findings of this study titled “The Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Young People’s Mental Health” has been made available in the funder's research repository RAY. We would like to thank the staff and students of the three participating secondary schools and their local authorities for permitting us to conduct this study. We would like to thank Dr Spencer Swain who commented on the earlier version of the paper. We would also like to thank the two anonymous expert reviewers who commented on the original submission of the paper. We declare that research ethics approval for this article was granted by York St John University ethics committee (Ref: ETH2223-0157). The authors conducted the research reported in this article in accordance with British Educational Research Association ethical guidelines (2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Academy of Medical Sciences. (2024). Prioritising early childhood to promote the nation’s health, wellbeing and prosperity. The Academy of Medical Sciences. Available from https://acmedsci.ac.uk/more/news/urgent-action-needed-on-failing-child-health.

- Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS). (2024). Childhood Matters: an ADCS Position Paper. Association of Directors of Children’s Services. Available from adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_Childhood_Matters_FINAL.pdf.

- Ball, S. J. (2023). The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228.

- Ball, S. J. (2017). The education debate (3rd ed.). Policy Press.

- Ball, S. J., & Olmedo, A. (2023). Care of the self, resistance and subjectivity under neoliberal governmentalities. In B. M. A. Jones & S. J. Ball (Eds.), Neoliberalism and education (pp. 131–142). Routledge.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Carli, L. L. (2020). Women, gender equality and COVID-19. Gender in Management, 35(7/8), 647–655. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2020-0236

- Cattan, S., Farquharson, C., Krutikova, S., McKendrick, A., & Sevilla, A. (2023). How did parents’ experiences in the labour market shape children’s social and emotional development during the pandemic? Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs.org.uk/publications/how-did-parents-experiences-labour-market-shape-childrens-social-and-emotional.

- The Children’s Society. (2022). The Good Childhood Report 2022. The Children’s Society. https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-09/GCR-2022-Full-Report.pdf.

- Clarke, M., Haines Lyon, C., Walker, E., Walz, L., Collet-Sabe, J., & Pritchard, K. (2021). The banality of education policy: Discipline as extensive evil in the neoliberal era. Power and Education, 13(3), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/17577438211041468

- Department for Education. (2022). State of the nation 2021: children and young people’s wellbeing. Research report. Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1053302/State_of_the_Nation_CYP_Wellbeing_2022.pdf.

- Feder, E. K. (2011). Power/knowledge. In D. Taylor (Ed.), Michel Foucault: Key concepts (pp. 55–68). Acumen.

- Foucault, M. (2020). Madness and civilisation. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault reader (pp. 123–167). Penguin.

- Hoffman, M. (2011). Disciplinary power. In D. Taylor (Ed.), Michel Foucault: Key concepts (pp. 27–39). Acumen.

- Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

- Kellett, M. (2005). How to develop children as researchers. Paul Chapman Publishing.

- Lawrance, E. L., Jennings, N., Kioupi, V., Thompson, R., Diffey, J., & Vercammen, A. (2022). Psychological responses, mental health, and sense of agency for the dual challenges of climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic in young people in the UK: An online survey study. Lancet Planetary Health, 6(9), e726–e738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00172-3

- Layard, R., & Dunn, J. (2009). A good childhood: Searching for values in a competitive age. Penguin.

- Lockyer, B., Endacott, C., Dickerson, J., & Sheard, L. (2022). Growing up during a public health crisis: A qualitative study of born in Bradford early adolescents during COVID-19. BMC Psychology, 10, 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00851-3

- Longfield, A. (2022). Hidden in Plain Sight: A national plan of action to support vulnerable teenagers to succeed and to protect them from adversity, exploitation, and harm. Final report by the Commission on Young Lives. Commission on Young Lives.

- Lundy, L., Byrne, B., Lloyd, K., Templeton, M., Brando, N., Corr, M., Heard, E., Holland, L., MacDonald, M., Marshall, G., McAlister, S., McNamee, C., Orr, K., Schubotz, D., Symington, E., Walsh, C., Hope, K., Singh, P., Neill, G., & Wright, L. H. V. (2021). Life under coronavirus: Children’s views on their experiences of their human rights. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 29(2), 261–285. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-29020015

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020). Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. The Health Foundation.

- Maynard, E., Warhurst, A., & Fairchild, N. (2022). Covid-19 and the lost hidden curriculum: Locating an evolving narrative ecology of schools-in-covid. Pastoral Care in Education, 41(3), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2022.2093953

- McKinlay, A. R., May, T., Dawes, J., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2022). You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts’: A qualitative study about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among young people living in the UK. BMJ Open, 12, e053676. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053676

- Mills, S. (2003). Michel Foucault. Routledge.

- Newlove-Delgado, T., Marcheselli, F., Williams, T., Mandalia, D., Davis, J., McManus, S., Savic, M., Treloar, W., & Ford, T. (2022). Mental health of children and young people in England 2022. NHS Digital.

- Nixon, J. (2012). Higher education and the public good: Imagining the university. Continuum.

- Rainer, C., Le, H., & Abdinasir, K. (2023). Behaviour and mental health in schools. Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition.

- Rubery, J., & Tavora, I. (2021). The COVID-19 crisis and gender equality: Risks and opportunities. In B. Vanhercke, S. Spasova, & B. Fronteddu (Eds.), Social policy in the European Union: State of play 2020. Facing the pandemic (pp. 71–96). European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) and European Social Observatory (OSE).

- Savin-Baden, M., & Howell Major, C. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

- Schoon, I., & Henseke, G. (2022). Social inequalities in young people’s mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do psychosocial resource factors matter? Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 820270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.820270

- Silverman, D. (2010). Doing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Soneson, E., Puntis, S., Chapman, N., Mansfield, K. L., Jones, P. B., & Fazel, M. (2023). Happier during lockdown: A descriptive analysis of self-reported wellbeing in 17,000 UK school students during Covid-19 lockdown. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(6), 1131–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01934-z

- Spiteri, J. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s mental health and wellbeing, and beyond: A scoping review. Journal of Childhood, Education & Society, 2(2), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.20212294

- Taylor-Robinson, D., Wickham, S., McHale, P., Bennett, D., Adjei, N., Esan, S. & Loopstra, R. (2023). Written evidence submitted by Health Inequalities Policy Research Group, University of Liverpool (PHS0153). The case for a focus on upstream childhood socio-economic conditions, particularly child poverty, as part of the prevention inquiry. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/117747/pdf/.

- UK Covid-19 Inquiry. (2023). INQ000221929 Witness Statement of David Cameron, Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Between 2010–2016, Dated 21/07/2023. Available from https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/documents/inq000221929-witness-statement-of-david-cameron-former-prime-minister-of-the-united-kingdom-between-2010-2016-dated-21-07-2023/.

- UK Covid-19 Inquiry. (2023). Opening statement of Covid-19 bereaved families for justice UK and Northern Ireland. Available from https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/documents/opening-statement-of-covid-19-bereaved-families-for-justice-uk-and-northern-ireland-covid-19-bereaved-families-for-justice-dated-12-june-2023/.

- UNICEF. (2022). From Learning Recovery to Education Transformation. Insights and Reflections from the 4th Survey on National Education Responses to COVID-19 School Closures. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/media/127286/file/From%20Learning%20Recovery%20to%20Education%20Transformation.pdf.

- UNICEF. (nd). How to reduce stress and support student well-being during COVID-19. Activities for teachers to support student mental health. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/teacher-student-activities-support-well-being.

- Wellington, J. (2015). Educational research: Contemporary issues and practical problems. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Widnall, E., Adams, E. A., Plackett, R., Winstone, L., Haworth, C. M. A., Mars, B., & Kidger, J. (2022). Adolescent experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures and implications for mental health, peer relationships and learning: A qualitative study in South-West England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 7163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127163

- Winter, R., & Lavis, A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on young people’s mental health in the UK: Key insights from social media using online ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010352

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental Health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

Appendix 1

Table A1. Survey and interview questions and coding themes.