Abstract

Global nursing scarcity was more evident during COVID-19. This study investigated the rates and contributing factors of turnover intention in the middle east through meta-analysis. Medline EMCARE, Cochrane, CINAHL, EMBASE, Ovid, Psych Info, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science databases searched, Protocol PROSPERO Registration Number was CRD42022337686. The turnover intention rate was 42.3% [CI: 40%, 44.6%]. Working environment, stress, deployment to COVID, fear of infection, long working hours, shift duties, and lack of social support were the major contributing factors.

Introduction/Background

Nurses and midwives are the largest healthcare professional group, constituting around 50% of the global healthcare workforce. However, according to a recent estimate by the WHO, 9 million more nurses and midwives will be needed by 2030. The emotional and physical stability of frontline nurses is very significant for safe and effective patient care (Hashim et al. Citation2012). Nurses’ turnover refers to the proportion of nurses that had to be replaced in each period to an average number of nurses and is generally viewed as the movement of nurses out of an organization (Gebregziabher et al. Citation2020).

Nurses’ turnover intention has been used in the nursing literature with different terms such as intention to leave, intention to quit, intention to stay, risk of quitting, and job retention intention (Kilańska, Gaworska-Krzemińska, and Karolczak Citation2020). The turnover intention has been allied to several adverse results such as medication error, falls, and pressure injuries. Moreover, it has been linked to increased healthcare system costs due to its impact on both financial and time resources (Falatah Citation2021).

Nurses in their everyday practice are dealing with various stressors, such as critical situations, workload, grief, death, nurses–physician collaboration and conflicts, and uncertainty about the effectiveness of the provided care (Kwiecień-Jaguś et al. Citation2018). According to a recent study that investigated stressors in the nursing profession during the pandemic, which 455 nurses expressed that nowadays have to deal with new sources of stress, such as personal protective equipment/supplies, exposure to SARS–COV2 and the possibility of infection. Nurses that are exposed to various stressors are not satisfied with their profession or the provision of low-quality care (Nashwan et al. Citation2021) which may increase their intention to leave nursing. In the COVID-19 outbreak, for example, turnover intention was studied as one of the consequences of COVID-19 caused by factors such as nurses’ anxiety and fear of COVID-19 (Lotfi et al. Citation2022). However, the rate of nurses’ turnover intention were not specified in the COVID-19 period, and only the presence of this problem in nurses has been reported in some studies.

Pandemic demands workload on nurses in an extreme work environment. The number of critical cases, the uncertainty about the disease, and the frequency of death from the disease impose psychological stress on nurses (Nikkhah-Farkhani and Piotrowski Citation2020). Considering the alarming issues of stress, burnout, and turnover among nurses even before the pandemic (Khattak et al. Citation2021), the pandemic might have amplified the issue of intention to leave among nurses. Thus, it was significant to study the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on Nurses’ turnover intention in the middle east region. The aim of this review is to Explore the turnover intention rate and contributing factors among nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the middle east region.

Method

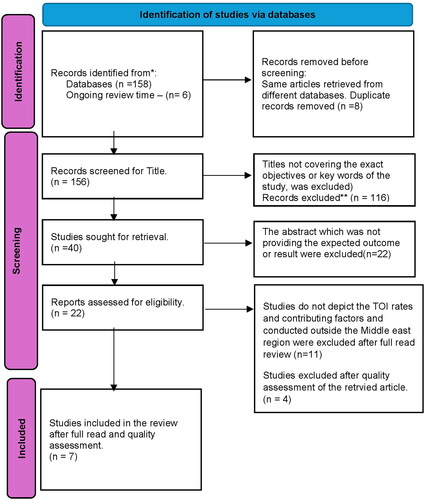

This review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for prevalence systematic reviews (Munn et al. Citation2018) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al. Citation2009). The review protocol has been published in PROSPERO (Registration Number CRD42022337686).

Search Strategy

An initial electronic search of MEDLINE and CINAHL MEDLINE and CINAHL was commenced to identify articles on the topic. The text words are contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms. Medline, EMCARE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, EMBASE, Journals Ovid, Psych Info, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for studies published between 2020 and 2022. On the three PEO components (Bettany-Saltikov Citation2016) population (i.e., nursing staff), exposure (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic), and outcome (i.e., turnover intention), This study refers to all types: “Turnover intention” was used as an umbrella term and (Turnover Intention OR Intention to Leave) AND (Nurses) AND (COVID-19) AND ("Qatar" OR "Jordan" OR "Saudi Arabia" OR "Iran" OR "United Arab Emirates" OR "Bahrain" OR "Oman" OR “Kuwait” OR “Egypt” OR “Iraq”) was used as key Words.

Study Type and Participants

Quantitative studies that investigated turnover intention rates and contributing factors among nurses in Middle east region were included in this review. Only studies conducted in different hospital settings in the middle east region, were eligible for inclusion.

Methodological Quality Evaluation

Two reviewers [KM,JK] independently appraised the included studies using the JBI critical appraisal checklists for analytical cross-sectional studies (scoring out of 8 questions) (Moola et al. Citation2017). Discrepancies were resolved through an appropriate discussion with a third reviewer (Lockwood, Munn, and Porritt Citation2015). Not Applicable answers were considered not achieved. If a study received a score of <60% on the quality assessment questions, it was excluded.

Results

The initial search resulted in 158 citations and the ongoing review process in 6 further records. Out of the 164 articles which entered the screening of titles, 40 articles were received after the screening, and 22 were received after the duplicate screening. Finally reached 11 articles after considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the review. Four articles received conflicting judgments from the two reviewers involved and were excluded because their scores were <60%. see for the search strategy and PRISMA chart.

Description of Studies

A total of seven publications was included in the final analysis. The studies selected were conducted only in the middle east region with Three studies from Iran, two studies from Saudi Arabia (n = 2,) and one study each from Egypt (n = 1) and Qatar (n = 1). All the studies were conducted between the years 2020 and 2022. The sample size for the studies ranges from 156 to 1101 (mean = 432.5). Most of the studies used a five-point Likert scale to assess the turnover intention (n = 5). Among these two studies utilized the TIS-6 scale which is a six-item tool, and the remaining three studies used three-item, 12-item, and 15-item tools. Two studies utilized yes or no questions.

Turnover Intention

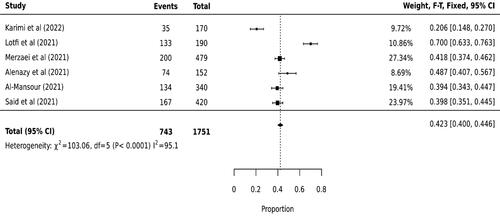

Six studies reported the percentage of nurses who had the intention to leave the organization and among them lowest rate was 20.6% and the highest rate was 48.6%. The highest turnover reported study was done in Saudi Arabia among adult and pediatric critical care nurses. One study from Qatar did not report the rate of intention to Turnover (Nashwan et al. Citation2021). However, they compared the turnover intention rate before and during COVID-19. The mean score revealed that turnover intention was significantly high (15.5) during the period of COVID-19 compared with before (13.2). The Meta-analysis was done with JBI SUMARAI and Turnover intention rates were reported in 6 included studies. The pooled data from six studies demonstrated that 42.3% (95% confidence interval [CI]: [40%, 44.6%]) of nurses have the intention to leave their organization, please see .

Table 1. Data extraction table: Turnover intention and contributing factors.

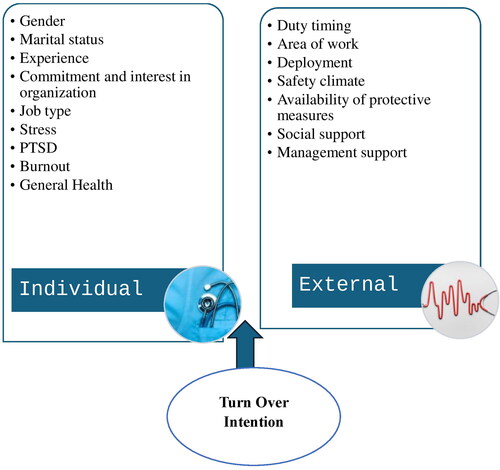

Significant Factors Contributing to the Turnover Intention

Socio-Demographic and Personal Characteristics and Turnover Intention

A study conducted in Saudi Arabia reported that female health workers including nurses (37.4%) had more turnover intention than their male counter partners (28%) (Al-Mansour Citation2021). Whereas a study done at Iran showing that mean of turnover intention was significantly correlated with the variable of gender with a higher turnover intention seen in men compared to women (β = −0.131, p = .002) during COVID-19 (Lotfi et al. Citation2022). A study done at Qatar reported that turnover intentions during COVID-19 among single (mean rank = 294.41) have high mean rank (p = 0.007) compared with nurses other marital status (mean rank = 225) and also there is a statistically significant difference (p = 0.023) among participants with different work experience, with nurses having 5–10 years of experience had higher mean rank (mean rank = 282.19) for the turn over intention compared with less than five year experience group (mean rank = 240.48)more working experience were likely to have higher turnover intention (Nashwan et al. Citation2021).

Organizational Factors, Working Environment, and Turnover Intention

Nurse practice environment(NPE) is reported as a significant predictor of nurses turnover intention (Alenazy, Dettrick, and Keogh Citation2021). Nurses’ sense of commitment, work conscience and their interesting in attending the organization had a positive influence on intention to stay at the organization and they are less likely to leave (Karimi, Raei, and Parandeh Citation2022). Safety climate of the organization is an important factor to stay back during the pandemic period. Inadequately organized atmosphere at the hospital, shortage of protective measures and measures taken to promote safety by the high-level management influencing the turnover intention of nurses (Lotfi et al. Citation2022). Job satisfaction is also a contributing factor to the intention to stay back in the organization (Karimi, Raei, and Parandeh Citation2022).

Stress, General Health, Social Support, Job Characteristics and Turnover Intention

The percentage of nurses with much and extreme stress were significantly increased(p = 0.000) during the pandemic period compared to before (Nashwan et al. Citation2021). Turnover intention had a significant and positive relationship with the post-traumatic stress disorder score (r = 0.348, p ˂ .01), job strain (r = 0.271, p ˂ .01) and general health (r = 0.311, p ˂ .01) (Mirzaei, Rezakhani Moghaddam, and Habibi Soola Citation2021). However, the social support and support from senior managers in the organization can mediate the effect of stress and reduce the turnover intention (Al-Mansour Citation2021). The personal accomplishment component of the Burn out is positively influencing the job leaving tendency (regression coefficient = −0.265, p = 0.01) of the nurses (Karimi, Raei, and Parandeh Citation2022). A positive significant correlation was found between turnover intention with job demand (r = 0.298, p ˂ .01) and job insecurity (r = 0.269, p ˂ .01) (Mirzaei, Rezakhani Moghaddam, and Habibi Soola Citation2021).

The job type, the area of work, timing and the type of hospital are also affecting the turnover intention. Those nurses had a better position showed less tendency to leave (p = 0.02), with nurse having less mean turn over intention score (6.40 ± 3.17) compared with nursing assistant (8.04 ± 2.65) (Karimi, Raei, and Parandeh Citation2022). Nurses working more than 40 h/week (p = .000), 3 or more night duties per week (p = .006) had more intention to leave from the current job (Said and El-Shafei Citation2021). Also, nurses working COVID-19 facilities, working in critical area, and deployed to critical area during COVID-19 had more intention to leave compared with others (Nashwan et al. Citation2021; Said and El-Shafei Citation2021).

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive systematic review on turnover intention among nurses in the middle east region. However, during the pandemic, this trend increases all over the world and a significant portion of nurses left their profession (Falatah Citation2021) but this review findings provide a comprehensive reflection of nurses’ TOI in the middle east region. The turnover intention is closely linked with the various extrinsic and intrinsic factors. The factors contributing to turnover intention before the pandemic was mainly due to personal, professional, patient, and organization-related factors (Ayalew et al. Citation2015; Falatah and Conway Citation2019). Whereas, during the pandemic, the major contributing factors of turnover intention were associated with a dramatic increase in workloads, lack of or adequate supply of material resources, emotional exhaustion, stress, and fear of infection (ICN Citation2020; Poku et al. Citation2022). This review revealed that the factors contributing to TOI were working environment, stress, current role, deployment to COVID facility, fear of infection to self and others, long working hours, shift duties, and lack of social support.

Women have higher attachment toward families and have concerns about infecting their families than men. Turn over intention also depends on differences reflect how social roles of women and men differ (Khalid et al. Citation2009; Zhang, Yang, and Wang Citation2021). However few studies highlights turn over intention is high among males, where men have more difficulty bearing a work setting that is stressful and out of control, especially during an outbreak of an infectious disease, and they are more likely to suffer from stress (Mirzaei, Rezakhani Moghaddam, and Habibi Soola Citation2021). Unmarried respondents are more likely to quit than those married, married medical professionals appeared to experience higher levels of job satisfaction than their counterparts. Married people have commitments and responsibilities which prevent them to take immediate decision to leave the job (Chen Citation2006; Ali Jadoo et al. Citation2015). Nurses with more working experience were likely to have higher turnover intentions that need the required work experience and specialized area of work may require to apply for nursing work abroad (Bautista et al. Citation2020).

Nurses facing such higher stress more likely to quit their jobs (Qureshi et al. Citation2013). Nurses who work during an outbreak of infectious disease often worry about their families due to the possibility of infection, which is a major barrier to their willingness to work. Varasteh, Esmaeili, and Mazaheri (Citation2022), found nurses were more afraid of infecting their families than being infected themselves. As per evidence people with more social support were less likely to think about leaving their jobs. Talking with friends and getting support helps the nurses to face challengers (Tetteh et al. Citation2020). Studies highlights that support from organization and colleagues act as great source of motivation. Nissly, Barak, and Levin (Citation2005) found organizational support (supervisor support), desirable job conditions and development of their job goals are operative ways to reduce stressors and ultimately reduce turnover intention. Evidences highlights that Poor mental and physical health of staff nurses’ has been linked to emotional exhaustion and low levels of empowerment leads to lack of career satisfaction and turnover intentions (Duran et al. Citation2021).

The previous studies identified many organizational factors and the working environment was associated with nurse turnover intention. A study found that the turnover intention was positively correlated with job insecurity and job demand which includes physical and psychological demands required for their current position (Barzideh, Choobineh, and Tabatabaei Citation2013). Supporting peer groups with sharing experience or formal peer supporters may improve the working atmosphere (Maben and Bridges Citation2020). The present study identified nursing practice environment, work position, personal accomplishments, lack of protective equipment, long working hours, shift work and interest in attending the organization were important factors associated with nurse turnover intention. During COVID, the reputation of the nursing profession has grown but the health and safety of nurses remained at risk. Healthcare institutions must take this opportunity to learn and reassess their system through a well-planned workplace protocol which consists of sets of actions to appropriate during a pandemic or epidemic outbreak, guidelines or pathways for caring for infected patients, safety practices among healthcare workers, necessary training and emergency response plans in collaboration local and national level agencies (Hirshouer, Edmonson, and Hatchel Citation2020).

Limitation

A limitation of the review was the inclusion of studies in English and limited to Middle east region only. In addition, various studies conducted about Turnover Intention in different region other than middle east which could not be included to obtain a comprehensive result.

Conclusion

The Frontline nurses are the backbone of health care delivery system. Unfolding emergency caused by the COVID-19 created significant stressors which are related to their physical working environment, increasing number of confirmed cases and heavy workload are putting nurses under intense pressure and high tendency to leave their organization. Retaining skilled and competent nurses are vital in any healthcare organization to improve the quality of their healthcare system. Leadership needs to focus on addressing their problems and protecting rights and benefits. Organizations that provide more support to their employees’ well-being are more likely to reduce stress and ultimately increase the employees’ intention to stay in the organization. However, organizations should understand the factors influencing employees’ turnover intentions and able to apply effective retention policies.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Mansour, K. 2021. Stress and turnover intention among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia during the time of COVID-19: Can social support play a role? PloS One 16 (10):e0258101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258101.

- Alenazy, F. S., Z. Dettrick, and S. Keogh. 2021. The relationship between practice environment, job satisfaction and intention to leave in critical care nurses. Nursing in Critical Care 28 (2):167–76. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12737.

- Ali Jadoo, S. A., S. M. Aljunid, I. Dastan, R. S. Tawfeeq, M. A. Mustafa, K. Ganasegeran, and S. A. R. AlDubai. 2015. Job satisfaction and turnover intention among Iraqi doctors: A descriptive cross-sectional multicentre study. Human Resources for Health 13 (1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0014-6.

- Ayalew, F., A. Kols, Y.-M. Kim, A. Schuster, M. R. Emerson, J. v Roosmalen, J. Stekelenburg, D. Woldemariam, and H. Gibson. 2015. Factors affecting turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. World Health and Population 16 (2):62–74. https://www.longwoods.com/product/24491. doi: 10.12927/whp.2016.24491.

- Barzideh, M., A. Choobineh, and S. H. Tabatabaei. 2013. Job stress dimensions and their relationship to job change intention among nurses TT- ابعاد استرس شغلی و ارتباط آن با قصد تغییر شغل در پرستاران. Iranian Journal of-Ergonomics 1 (1):33–42. http://journal.iehfs.ir/article-1-24-fa.html.

- Bautista, J. R., P. A. S. Lauria, M. C. S. Contreras, M. M. G. Maranion, H. H. Villanueva, R. C. Sumaguingsing, and R. D. Abeleda. 2020. Specific stressors relate to nurses’ job satisfaction, perceived quality of care, and turnover intention. International Journal of Nursing Practice 26 (1):e12774. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12774.

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. 2016. EBOOK: How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: A step-by-step guide.

- Chen, C. F. 2006. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and flight attendants’ turnover intentions: A note. Journal of Air Transport Management 12 (5):274–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2006.05.001.

- Duran, S., I. Celik, B. Ertugrul, S. Ok, and S. Albayrak. 2021. Factors affecting nurses’ professional commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management 29 (7):1906–15. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13327.

- Falatah, R. 2021. The impact of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic on nurses’ turnover intention: An integrative review. Nursing Reports (Pavia, Italy) 11 (4):787–810. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11040075.

- Falatah, R., and E. Conway. 2019. Linking relational coordination to nurses’ job satisfaction, affective commitment and turnover intention in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Nursing Management 27 (4):715–21. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12735.

- Gebregziabher, D., E. Berhanie, H. Berihu, A. Belstie, and G. Teklay. 2020. The relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses in Axum comprehensive and specialized hospital Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Nursing 19 (1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12912-020-00468-0.

- Hashim, A. E., Z. Isnin, F. Ismail, N. R. M. Ariff, N. Khalil, and N. Ismail. 2012. Occupational stress and behaviour studies of other space: Commercial complex. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences 36 (June 2011):752–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.082.

- Hirshouer, M., J. C. Edmonson, and K. K. Hatchel. 2020. Hospital preparedness. Nursing Management of Pediatric Disaster 301–14.

- ICN 2020. The global nursing shortage and nurse retention. Nursing 13–7.

- Karimi, L., M. Raei, and A. Parandeh. 2022. Association between dimensions of professional burnout and turnover intention among nurses working in hospitals during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in Iran based on structural model. Frontiers in Public Health 10 (May):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.860264.

- Khalid, S. A., H. K. Jusoff, H. Ali, M. Ismail, K. M. Kassim, and N. A. Rahman. 2009. Gender as a moderator of the relationship between OCB and turnover intention. Asian Social Science 5 (6):108–17. doi: 10.5539/ass.v5n6p108.

- Khattak, S. R., I. Saeed, S. U. Rehman, and M. Fayaz. 2021. Impact of fear of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of nurses in Pakistan. Journal of Loss and Trauma 26 (5):421–35. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1814580.

- Kilańska, D., A. Gaworska-Krzemińska, and A. Karolczak. 2020. Work patterns and a tendency among Polish nurses to leave their job. Medycyna Pracy 70 (2):145–53.

- Kwiecień-Jaguś, K., W. Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, A. Chamienia, and V. Kielaite. 2018. Stress factors vs. Job satisfaction among nursing staff in the Pomeranian province (Poland) and the vilnius region (Lithuania). Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine: AAEM 25 (4):616–24. doi: 10.26444/aaem/75801.

- Lockwood, C., Z. Munn, and K. Porritt. 2015. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3):179–87. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062.

- Lotfi, M., O. Z. Akhuleh, A. Judi, and M. Khodayari. 2022. Turnover intention among operating room nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak and its association with perceived safety climate. Perioperative Care and Operating Room Management 26 (December 2021):100233. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2021.100233.

- Maben, J., and J. Bridges. 2020. Covid-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29 (15–16):2742–50. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15307.

- Mirzaei, A., H. Rezakhani Moghaddam, and A. Habibi Soola. 2021. Identifying the predictors of turnover intention based on psychosocial factors of nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak. Nursing Open 8 (6):3469–76. doi: 10.1002/nop2.896.

- Liberati, A., D. G. Altman, J. Tetzlaff, C. Mulrow, P. C. Gøtzsche, J. P. A. Ioannidis, M. Clarke, P. J. Devereaux, J. Kleijnen, and D. Moher. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 339 (jul21 1):b2700–b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Moola, S., Z. Munn, C. Tufanaru, E. Aromataris, K. Sears, R. Sfetcu, & K. Lisy. 2017. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 5.

- Munn, Z., M. D. J. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Nashwan, A. J., A. A. Abujaber, R. C. Villar, A. Nazarene, M. M. Al-Jabry, and E. C. Fradelos. 2021. Comparing the impact of covid-19 on nurses’ turnover intentions before and during the pandemic in Qatar. Journal of Personalized Medicine 11 (6):456. doi: 10.3390/jpm11060456.

- Nikkhah-Farkhani, Z., and A. Piotrowski. 2020. Nurses’ turnover intention a comparative study between Iran and Poland. Medycyna Pracy 71 (4):413–20. doi: 10.13075/mp.5893.00950.

- Nissly, J. A., M. E. M. Barak, and A. Levin. 2005. Stress, social support, and workers’ intentions to leave their jobs in public child welfare. Administration in Social Work 29 (1):79–100. doi: 10.1300/J147v29n01_06.

- Poku, C. A., J. N. Alem, R. O. Poku, S. A. Osei, E. O. Amoah, and A. M. A. Ofei. 2022. Quality of work-life and turnover intentions among the Ghanaian nursing workforce: A multicentre study. PloS One 17 (9):e0272597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272597.

- Qureshi, M. I., M. Iftikhar, S. G. Abbas, U. Hassan, K. Khan, and K. Zaman. 2013. Relationship between job stress, workload, environment and employees turnover intentions: What we know, what should we know. World Applied Sciences Journal 23 (6):764–70. doi: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.23.06.313.

- Said, R. M., and D. A. El-Shafei. 2021. Occupational stress, job satisfaction, and intent to leave: Nurses working on front lines during COVID-19 pandemic in Zagazig City, Egypt. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28 (7):8791–801. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11235-8.

- Tetteh, S., C. Wu, C. N. Opata, G. N. Y. Asirifua Agyapong, R. Amoako, and F. Osei-Kusi. 2020. Perceived organisational support, job stress, and turnover intention: The moderation of affective commitments. Journal of Psychology in Africa 30 (1):9–16. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2020.1722365.

- Varasteh, S., M. Esmaeili, and M. Mazaheri. 2022. Factors affecting Iranian nurses’ intention to leave or stay in the profession during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Nursing Review 69 (2):139–49. doi: 10.1111/inr.12718.

- Zhang, Y., M. Yang, and R. Wang. 2021. Factors associated with work–family enrichment among Chinese nurses assisting Wuhan’s fight against the 2019 COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Nursing (January):1–12. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15677.