ABSTRACT

We commonly evaluate search engines and the results they return, but what grounds those evaluations? One straightforward way of evaluating search engines appeals to their ability to satisfy the goals of the user. Are there, in addition, user-independent norms, that allow us to evaluate search engines in ways that may come apart from their ability to satisfy the individuals who use them? One way of grounding such norms appeals to moral or political considerations. I argue that in addition to those norms, there are also distinct user-independent epistemic norms that apply to search engines. Evaluating search engines relative to them, however, requires us to appreciate the impact search engines have on our practices and norms of inquiry more broadly: by systematically altering the accessibility of information, search engines don’t just give us information but shape our collective imagination, and the categories it operates over.

We commonly evaluate search engines as better or worse than one another. Sometimes we describe them as ‘getting it wrong’ when they return an obviously implausible or inappropriate result. What norms ground these evaluations? One natural way to understand them is as relative to the intentions or goal that the user has or could reasonably have had at the time of performing the search. A good search engine helps user to meet their goals. In this paper, I will argue that user-relative evaluation cannot accommodate the full range of evaluations we want to make of search engines. Instead, we might appeal to moral or political norms which can come apart from the intentions of users or their individual interests. I argue that there are, in addition, a set of user-independent epistemic norms that apply to search engines. On epistemic grounds, some information should be returned in response to a given inquiry, even if it does not serve the goals of the user of the search engine at that time.

Before we can subject a search engine to any kind of evaluation, however, we first need an account of the nature of the task it is attempting to perform. Only then can we begin the process of figuring out whether it has done so well or badly. I claim that a search engine has two tasks, to first identify and then to answer a question. Previous work often assumes that search engines strive to return results that are relevant to the search terms used but does not offer an account of what it takes for results to be relevant. Conceiving of search engines as striving to answer a question allows us to understand relevance as question-relative: results are relevant when they narrow down the partition of logical space imposed by the question in hand. However, we can only return a full evaluation of a search engine when we can also evaluate their performance on the first task: the disambiguation of the user's inquiry. And to do that, we need to appreciate the ways in which the interpretation of questions imposes a partition on logical space which has broad ethical and pragmatic implications. These flow primarily from the way in which it affects the accessibility of information. Search engines resolve indeterminacy in the questions we ask in a way that ultimately shapes both the collective imagination and the categories over which it operates. But this process is not extra-epistemic: it occurs through a core epistemic feature, the relative accessibility of information.

I proceed as follows: In Section 1, I describe the kinds of evaluative practices we adopt in regard to search engines, and which I seek to ground. In Section 2, I explain what I take a search engine to be, and some of the ways in which we use them. I will focus on cases where a search-engine responds to a search for information with an ordering of webpages. In these cases, a search engine has a two-stage task of identifying an inquiry, and then directing users to information that is relevant to it. With this account in hand, I turn to considering how we can ground the evaluations we make of search engines, by identifying the norms relative to which we are performing these evaluations. In Section 3, I argue that user-relative evaluations, though clearly important, cannot support some significant evaluations we want to make of search engines. In Section 4, I outline some of the ways in which moral and political norms have been applied to search engines, and suggest that this application often relies on an underlying set of objective, epistemic norms. And so in Section 5, I argue that in addition, we can and do evaluate search engines relative to a set of epistemic norms. I give an account of these norms in terms of relevance to a question. In Section 6, I consider the messier, more complex part of the evaluative framework: evaluating the disambiguation of the user’s question. That requires us to appreciate the ways in which search engines don’t just respond to our inquiries, but through their disambiguation of our search terms, shape our practices of inquiry in ways that have wide-ranging consequences for the relative accessibility of information. The accessibility of information in turn plays a role in determining what matters to us, collectively; the imaginative spaces we can occupy; and the constitutive properties of social kinds.

1. Search engines can get it wrong

We often normatively evaluate search engines: we describe them as better or worse than one another. Sometimes when the results are patently absurd or inappropriate, we describe them as getting it wrong. But what does it mean for a search engine to get it wrong?

Sometimes this can be quite straightforward: occasionally, search engines attempt to offer a direct response to a question a user asked (‘how tall is Stephen Colbert?’), and that response may be inaccurate (Gesenhues Citation2015). Sometimes search engines make suggestions for what users are looking: when looking for Tyler Burge’s well-known article ‘Sinning Against Frege’, a library search engine asked ‘Did you mean “Winning Against Frege”’? In doing so, the library engine got it wrong in the sense that it was mistaken about my intentions. But it also seemed to get in wrong more broadly: given that there is no such article, whereas there is an influential article with the name I had directly searched for, it doesn’t seem reasonable to suggest that I had mistyped my search.

These cases are relatively simple to evaluate: we can point to norms of accuracy to explain the way in which the search engine has malfunctioned. I did not mean ‘winning against Frege’ so the engine is wrong to suggest that I did. If Stephen Colbert is 5′11″ then the search engine is wrong when it says otherwise. More perplexing is our sense that search engines can ‘get it wrong’, or at least be better or worse than one another, when they are offering us not a direct answer to a question or an interpretation of our intentions that can be accurate or inaccurate, but an ordering of webpages. Many people have preferences for which search engines they use which are based on a sense that that search engine is ‘better’ than its competitors. This reveals that we have an implicit framework against which we are able to evaluate and compare the results search engines produce. But what is that framework? What norms are we evaluating search engines against? Clearly, some intuitive notion of relevance is playing a role here, but what does that amount to, and does it exhaust the kinds of evaluation to which we can subject search engines?

This question becomes more urgent when we consider recent work highlighting the ways in which search engine algorithms can instantiate and perpetuate bias against marginalised social groups. Consider, for instance, Safiya Noble’s experience in 2011 of entering the search terms ‘black girls’ when looking for information relevant to activities she might do with her teenage nieces. The search engine she used returned as its top results exclusively webpages with highly sexualised content, apparently operating on the assumption that she had been looking for pornography (Noble Citation2018). Intuitively, something has gone awry here – but what?

Returning results of this kind are one of the ways in which search engines can contribute to what Ruha Benjamin terms the New Jim Code, ‘the employment of new technologies that reflect and reproduce existing inequities but that are promoted and perceived as more objective or progressive than the discriminatory systems of a previous era’ (Benjamin Citation2019, 5–6). We perceive algorithms, and platforms such as search engines which rely on them, as immune to some of the biases that might afflict humans performing a similar task. And yet their outputs contribute to the on-going oppression of minority groups by, for instance, reinforcing an association between black women and pornography to the exclusion of other information. Describing more fully the norms which apply to search engines, will position us to identify more precisely the full range of ways in which the New Jim Code is problematic.

Search engines have changed: sexualised search results are no longer among the first offered in response to the terms ‘black girls’, or others like it. Search engines have also altered how they handle demographic search terms, making it harder to access antisemitic or homophobic results. But have they changed for the better, and how do we decide if that is the case? In this paper, I begin to build the framework we need to answer these questions, by identifying and describing the various norms which apply to search engines. My goal is to argue, firstly, that these go far beyond ‘user-relative’ norms of evaluation, and secondly, that they include distinctively epistemic and zetetic norms.Footnote1

2. What is a search engine?

At its broadest, a search engine is a piece of software that orders items in a database in response to particular search terms. Some search engines operate over a very limited domain, for instance, a simple search engine in a library operates over a database which just includes the items in that library. The search engines we are most familiar with operate instead over the broader domain of the internet at large. Internet search engines operate via a three-stage process (Roth Citation2019). The first stage involves trawling the relevant domain for sites using ‘spiders’ – bots that identify websites and their content. In the second stage, the search engine indexes those sites on the basis of various properties, and in the third stage, they apply algorithms that deliver an ordering of sites relative to the particular search terms a user has inputted. That indexing and ordering is performed, by most contemporary search engines, on the basis of two broad sets of features, which we could think of loosely as semantic features and syntactic features. Semantic features relate to the content of the webpage: does the search term occur in the page itself, and with what frequency? Sophisticated search engines will also look for content that is semantically related to, though distinct from, the search terms themselves (it will use the association between daffodils and bulbs, for instance, to return more relevant search results though your search only included the former term). Syntactic features are other, structural aspects of the website: how many links does it have to other sites (Brin and Page Citation1998)? How long do most users stay on the website? How much content is on the page?

Search engines serve no single purpose for us, beyond the very general one of helping us to navigate the internet. It will help us to distinguish some of the more specific things we do with them from one another. Sometimes we use search engines as, in effect, a form of transport. Rather than type in the full address for a website, I might just search for some key term instead, trusting that the search engine will return the site I’m after as its top hit. Sometimes we use search engines to access not information per se, but rather a set of resources of some kind – music videos, or pornography. At other times we use search engines to find a service near us, rather than on the internet itself, as when we search for mechanics, or health food shops.

I am most interested in cases when we use a search engine primarily to find information. Again, this takes a range of forms: we can distinguish at least four. Sometimes we want an answer to a specific question, such as ‘what date is Passover this year?’ Other times we’re looking for an answer to a more diffuse question, that doesn’t have a simple right or wrong answer such as ‘what is hermeneutics?’ or ‘how do you cook mana’eesh?’, ‘how does evolution work?’ or ‘why do marsupials keep their young in pouches?’. Going up a further level of generality, sometimes we have no particular question in mind but are instead interested in understanding what kinds of questions we might ask about a given topic, in which case we might just use a very general search term like ‘marsupials’ ‘evolution’ or ‘mana’eesh’.Footnote2 Finally, we sometimes use search engines to find out information about search engines themselves and the internet more broadly. For instance, hearing that Google returns an amusing or inappropriate response to certain terms you might try typing them in to see what happens. We may also use a search engine to serve multiple different ends at the same time: a search for information often gives us information about how search engines or society at large respond to certain terms whether that’s something we are actively seeking or not.

I am primarily interested in cases where the search engine responds to a search for information with an ordering of webpages. Against what standards are we evaluating a search engine when it offers us not a direct answer but a set of webpages?

To answer this question, we first need a way of conceptualising the task the search engine is performing in these cases, such that a list of websites could potentially provide an appropriate response to it, and such that different orderings of webpages can provide better or worse responses than one another. How we conceptualise the task a search engine performs will in part determine the evaluative resources we can appropriately apply to it. Someone running a race isn’t normally criticisable for their failure to sing a light operetta whilst doing so. The task in hand – running the race – sets the parameters relative to which their performance can be evaluated.

I first want to set aside two significant features of search engines which complicate our evaluation of them. The first is that all major search engines are run by profit-making companies. They operate within a complex financial incentive structure, which is often invisible to the user. This skews their design away from the generation of maximally relevant or satisfactory results towards results that serve the financial ends of the company (Noble Citation2018; Benjamin Citation2019; Introna and Nissenbaum Citation2000). Their goal, in practice, is not to simply return information, it is to generate revenue from the process of responding to users’ inquiries.Footnote3 The impact this has on their operation cannot be overestimated. So why think that I can set it aside in order to arrive at an evaluative framework of them? All of the examples I draw on are generated by search engines that operate with profit motives. However, it is not, at a conceptual level, part of the task of a search engine to generate profit. That is a contingent feature of their actual operation. One reason for undertaking this inquiry is to arrive at norms that could help us evaluate the distorting impact of that profit motive on search engines. But to do so, we must first consider the task and operation of search engines in abstraction from that. The project I undertake here is prior to a full understanding of the problems to which this financial incentive structure gives rise.

Secondly, many search engines offer results to users about whom they have very large quantities of data concerning previous searches, location, email, shopping history, and so on, in addition to data about the searches made by other users who share those characteristics. For the most part, I will set aside the ability of search engines to personalise searches in this way. I do so because search engines can and often do operate without that knowledge, and because it is cleaner to conceptualise and evaluate their performance before we consider the ways in which that task changes in light of that information about the searcher.

What are we doing when we type search terms into a search engine? I propose that we think of ourselves as asking a question of the search engine. That gives the search engine two tasks: first, it must correctly identify the question, which is often underspecified by the search terms actually used. Secondly, it must then make some move towards answering it. But how can a list of webpages provide an answer to a question? This is clearly not an attempt to directly answer the question itself. In most other contexts, simply providing a list of resources in response to a question does not constitute a cooperative answer. So what is the kind of inquiry to which an ordered series of webpages could constitute an appropriate response?

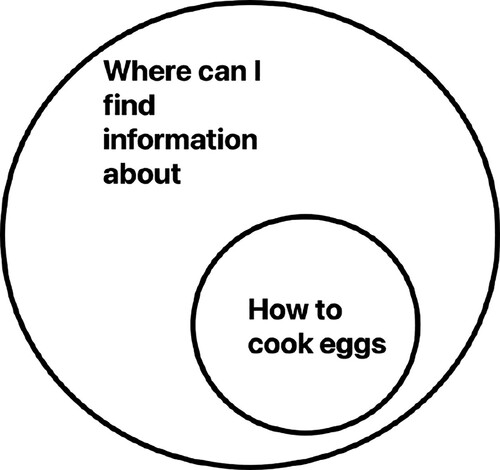

Suppose a friend asks me how to cook a grilled cheese sandwich, and in response I provide a list of recipe books or instructional videos. In this case, I am not answering the question ‘how do I make a grilled cheese sandwich’ directly. Instead, I appear to be answering the question ‘where can I find information about how to make a grilled cheese sandwich?’ Similarly, the search engine’s response seems appropriate if we think of a user making an indirect, or nested inquiry of the search engine. When the user types in ‘how to cook eggs’ they are not asking the search engine directly ‘how do I cook eggs?’ but rather ‘where can I find information about how to cook eggs’.Footnote4 The results the search engine returns ideally reflect the probability that the user will find accurate information relevant to the question of how to cook eggs on those pages (Figure).Footnote5

Figure 1. Search for ‘how to cook eggs’ understood as a nested inquiry into where to find information about how to cook eggs.

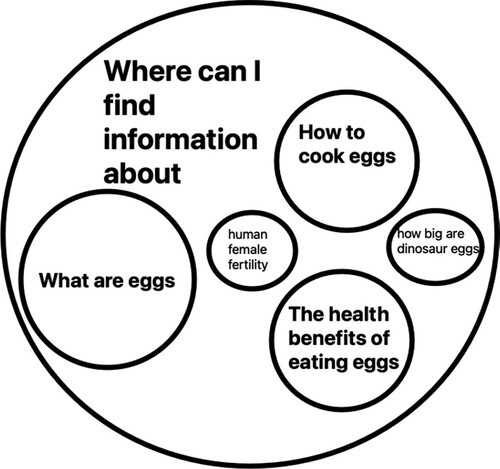

Figure 2. Search for ‘eggs’ understood as a nested inquiry into where to find information about a range of more specific questions.

How are we to understand cases where the user enters search terms which fail to identify any determinate inquiry, such as a search for ‘hermeneutics’? In this case, we could think of the search engine as responding to the question ‘where can I find information about [a set of questions that constitute a reasonable disambiguation of the search terms employed]’ (Figure ).

This is not to say that we have to impute the intention to ask that nested set of questions to the user: they may have no very clear goal in mind. Rather, we should think of the task the search engine undertakes as an attempt to provide information capable of answering that nested set of questions, and evaluate it accordingly, (and it may do better to offer responses which answer a spread of these questions rather than just one).

Why should we accept this characterisation of the task a search engine undertakes? Firstly, as I have already claimed because it makes sense of how an ordered list of webpages could constitute an appropriate response to certain search terms. And secondly, as I shall go on to show because this provides us with the framework we need to make good sense of our evaluative practices of search engines. Perhaps it will turn out further down the line that some alternative construal makes better sense of these, but it is worth seeing what resources this one offers us at least.

A final preliminary worry we might have is whether search engines are themselves ever the proper target of direct normative evaluation. Why not think it is primarily the creators and users of these tools that are the relevant locus of evaluation? One might think that the problem Safiya Noble encountered simply reflects the use that has been made of the search engine: the search engine is criticisable only in so far as that usage is (for instance, if accessing pornography constitutes a form of sexual exploitation, or more specifically to this case, because in accessing race-specific pornography users are participating in a problematic practice of sexually objectifying a marginalised subgroup). According to this view, search engines are suboptimal when they have been corrupted by suboptimal use. Search engines that have adapted to the morally bad intentions of users can themselves be subject to criticism as a result of that adaptation: we can evaluate them only derivatively. This route simplifies things: there is no special problem of how we evaluate search engines themselves, since the primary locus of evaluation is their users, and we already have a wide range of evaluative tools that apply to people.Footnote6

This displacement of the locus of evaluation from engine to user underestimates the way in which users’ goals and behaviours are not static but are themselves in a dynamic relationship with the algorithms driving search engines. Knowing you can access pornography simply by using a descriptor for a demographic category encourages the use of those terms to do so, if that is your goal. The problematic use that users make of search engines is itself facilitated by the behaviour of the search engines. Users adapt their behaviours in light of their knowledge of the rewards the search engine will give them.Footnote7 We need ways of evaluating search engines that can do justice to their role in that relationship, by directly evaluating the search engines themselves.Footnote8

With this framework in hand, I turn now to the question of what the set of norms are against which we evaluate a search engine when we do so.

3. User-relative evaluation

At this stage it might seem like the answer to the question ‘against what set of norms do we evaluate search engines’ is very simple. Search engines are designed to satisfy the intentions of the user, or to help the user achieve their goals, and it is relative to this task that we should assess them: a good search engine is one that satisfies the intentions or facilitates the goals of its users.Footnote9

The assumption that this is what search engines aim at is reflected in the early literature on ways of evaluating search engines which, drawing on existing work on information retrieval more broadly, assumes a ‘Probability Ranking Principle’ according to which results should be ordered in terms of decreasing expected relevance (Robertson Citation1977b), and which tends to then equate relevance with the satisfaction of the users of the information retrieval system. Maron and Kuhns, for instance, suggest that information retrieval systems aim to provide ‘an ordered list of those documents which most probably satisfy the information needs of the user’ (Maron and Kuhns Citation1960, 216).Footnote10

This is clearly a legitimate and important way of evaluating a search engine. What is up for debate is whether this exhausts the normative resources we can apply to them. And here I think the answer is clearly no. This does not exhaust the kind of appraisals we intuitively, and legitimately, make of search engines.

In the first place, notice that when users have incoherent or poorly executed goals, we don’t fault search engines for failing to satisfy them. For instance, if someone types in ‘vehicle registration’ hoping for information about vehicles of representation and sensory registration it doesn’t seem fair to blame a search engine for returning results to do with the registration of motor vehicles instead. This indicates that our evaluations of search engines are not entirely hostage to the intentions and idiosyncrasies of individual users, as a crude form of user-relative evaluation would predict.Footnote11 At the very least, we need to either average over many users and evaluate search engines relative to their ability to satisfy users intentions in general, or evaluate them relative to some minimally idealised user, who behaves in a predictable way and pursues reasonable strategies to achieve their goals.

Neither of these strategies is straightforward. If we appeal to an idealised user, we face the question of what makes this user ideal. We can only specify the relevant features of such a user – that they always use the search terms most appropriate to their inquiry in an optimally rational fashion, or that they only approach a search engine with the most upstanding of moral intentions – by appeal to some independent set of background norms. So we have really just deferred the question of what normative framework applies to search engines onto the question of what makes a user an ideal user. This approach presupposes some more robust normative framework, applicable to search engines, that goes beyond the intentions or goals of actual users, that allows for the designation of an ideal user.

Could we avoid that if we simply evaluate search engines by their ability to satisfy users in general, allowing idiosyncratic, irrational use of search engines to wash out in the mix? Implicitly, this is how we often assume search engines are designed to operate, that they in fact respond with whatever results would satisfy the majority of users. And that assumption can offer a potential legitimation of the results search engines arrive at: if those results simply reflect what more people are looking for then the search engine is operating in a somewhat democratic fashion by returning the results it does.Footnote12 If a user is left frustrated by the results, then it is they who is at fault for their atypical use of the search engine. This approach might respond to the Noble case by suggesting that she should not have been surprised by the sexualised results her search returned. She should have anticipated that the majority of users entering those terms would be looking for pornographic material and expected that to be reflected in the results. This implies a normative framework for search engines where the intentions of the majority of users provide a standard for the assessment of their performance, even in cases where the individual’s goals depart from the majority.

The first thing to worry about here is who exactly this majority is. It is likely that the number of black women and girls vastly exceeds the number of people to whose searches the algorithm is responsive in generating this particular set of results. Assuming these results don’t serve their interests, they seem subject to a form of disenfranchisement by the supposedly democratic functioning of the search engine. For this response to succeed, the relevant constituency has to be restricted to those actually using the search engine and entering those search terms. That is not a majority of potential search engine users in any straightforward sense. We need a rationale for why that minority group should determine the results returned before we can claim the democratic mandate alluded to above.Footnote13

In response, it might be claimed that this problem, of a minority determining what information is returned in response to demographic terms, will wash out once access to the internet improves. Then we will be in a position to simply allow majority usage and interests to set the normative standards for search engines.

Abstracting away from the Noble case, the broader worry that arises here is that search engines operate in a range of ways to exclude minority interests, and allowing the satisfaction of the majority of users to set their normative standards fails to recognise the significance of that. Introna and Nissenbaum describe the way in which

[i]n the current, commercial model, search engines wishing to achieve greatest popularity would tend to cater to majority interests. While markets undoubtedly would force a degree of comprehensiveness and objectivity in listings, there is unlikely to be much market incentive to list sites of interest to small groups of individuals, such as individuals interested in rare animals or objects, individuals working in narrow and specialized fields or, for that matter, individuals of lesser economic power, and so forth. (Citation2000, 177)

One way of approaching the problem would be to not simply average over user satisfaction, but to develop a more complex scoring rule, one that took into account, for instance, the strength of user preferences, or the extent of their frustration.Footnote14 But it is hard to imagine such a metric succeeding in arriving at a functional search engine without it also excluding highly morally problematic intentions, or weighting minority interests more heavily to allow them to count against the majority. And as soon as we include those elements, then we are, once again, appealing to some more objective standard of assessment that goes beyond the satisfaction of users.

4. Moral and political evaluation

The picture grows more complex still when we notice further ways in which we are happy to disregard certain user intentions as irrelevant to the assessment of the search engine. Many search engines are deliberately designed to frustrate some of the morally problematic intentions of their users, implying that by some intuitive set of standards a good search engine can be one that fails to satisfy at least some subset of users’ intentions. This adds further support to the claim that the ability to satisfy users does not exhaust the norms which apply to search engines.

In 2016 Google deliberately altered its autocomplete suggestions for searches beginning with ‘Jew’ to avoid the highly antisemitic searches which were being automatically suggested, such as ‘are Jews evil’ (Gibbs Citation2016). In making that change, Google will have frustrated the goals of at least some of the users who were employing the search term ‘Jew’. The autocomplete suggestions for many demographic terms are similarly edited (if you try searching for ‘why are women … ’ Google offers only neutral or positively valenced suggestions for completion of the search. Not so if you search for ‘why are academics … ’). Given the sensitivity of search engine results and suggestions to the behaviour of previous users, it is reasonable to infer that these changes may be frustrating a good number of users. But that need not make the search engine worse. This can be explained if we allow that moral or political norms apply to search engines, in addition to norms of helping users achieve their goals.

There is an established literature describing some of the ways in which we can evaluate search engines in moral or political terms (H. Tavani Citation2020), and my intention here is only to establish that such norms do not exhaust the limits of our evaluation of them, that we need, in addition distinctively epistemic norms. Some of the work in this area considers a range of problematic social and economic effects that search engines can have, and their moral and political ramifications (Noble Citation2018; Benjamin Citation2019).Footnote15 Other work focuses on the impact of search engines on users’ privacy or their right to transparent knowledge of how the algorithms driving search engines work (Tavani Citation2005; Castillo Citation2019). An alternative approach focuses on the role of search engines within a democratic polity (Diaz Citation2008; Introna and Nissenbaum Citation2000; Hinman Citation2005). Promoting various democratic ends might mandate restrictions on the results that search engines can return, or the promotion of certain information, even when that runs counters to the goals of a good number, perhaps even the majority, of individual users.

For our current purposes, the key thing to notice is that many of these approaches presuppose a more basic, underlying epistemic norm. Consider work by Introna and Nissenbaum which argues for access to information as a public good, one that justifies interventions in how search engines operate:

the value of comprehensive, thorough, and wide-ranging access to the Web lies within the category of goods that Elizabeth Anderson describes in her book Values in Ethics and Economics as goods that should not be left entirely (if at all) to the marketplace (Anderson, Citation1993). (Citation2000, 178)

Alternatively, Dag Elgesem roots moral norms for search engines in Kantian ideals for the public use of reason. He suggests that search engine companies ‘are morally required to make it possible for users to act as rational searchers to as large an extent as possible’ (Elgesem Citation2008, 235). In this way, his account roots a moral norm for search engines in an underlying epistemic end: subjects should be able to act as rational searchers. But that in turn presupposes a conception of rationality and its application within the context of internet search, which relies on a prior set of epistemic norms.

Similarly, Carlos Castillo discusses the need for a measure of fairness in information retrieval, which might decompose into other elements including a norm of ‘sufficient presence of items belonging to different groups’ and ‘proper representation of items, particularly disadvantaged / protected groups, that prevent representational harms to members of these groups’ (Castillo Citation2019, 65). Again, these are complex normative notions which presuppose some underlying epistemic (or at least hybrid) informational norm. Take the Noble case, for instance. Intuitively, the results returned fail to meet the norms of sufficient presence and proper representation, but against what benchmark are we assessing them when we make that claim? The political ideal of fair representation relies on a more basic epistemic norm of relevance to an inquiry, but how are we to break that down?Footnote16

5. Epistemic evaluation: relevance

Search engines play a role in facilitating access to information. But what constitutes adequate access? Under certain circumstances, it seems permissible, perhaps even mandatory for good search engines to prioritise some information above other information even when that frustrates the intentions of the user. The reasons for doing so are moral, or political: discouraging violence, or racist, sexist or antisemitic attitudes, for instance.

I want to argue that we can go further than this, that some information ought to be available, and indeed prioritised (a requirement on meaningful availability), in response to a given search even if users do not want it, on epistemic grounds. And a corollary of that is that some information ought not to be available to users, even if it would satisfy them better than the information that is prioritised, on epistemic grounds (this claim is a corollary of the preceding one on the assumption that prioritising some information so as to render it meaningfully available comes at the cost of deprioritising other information).Footnote17

Why should we think that is the case? The problem in the Safiya Noble case is not just that it is morally problematic if a search engine prioritises sexualised content in response to the terms ‘black girls’, it’s that those results are, by some objective metric, not the most relevant to the search terms. They represent one aspect of the subject matter, but many other sites would be, intuitively more relevant.Footnote18 But what do we mean by relevance in this context? The early literature on information retrieval tended to either avoid unpacking the notion further (Robertson Citation1977b) or to equate relevance with utility to the user (Maron and Kuhns Citation1960), but we have seen above that that is unsatisfactory. What other notions of relevance are available to us?

Clearly, we are not interested in a notion of evidential relevance, whereby relevant information changes the probability of a given hypothesis: we have no candidate hypothesis in view. Nor are we interested in a notion of psychological relevance, whereby the information delivers cognitive reward to the user (Sperber and Wilson Citation1994) since we are specifically concerned to find a metric that abstracts away from the idiosyncrasies of individual users, their intentions, and what they find rewarding.

More hopeful is the notion of relevance to an askable question, whereby something is relevant if it is a reason for accepting or rejecting some answer to that question (Cohen Citation1994). A version of this is more precisely developed into the concept of conversational relevance, according to which a contribution to a conversation is relevant to a question under discussion if it either introduces a partial or full answer to it, or is part of a strategy to arrive at an answer to it (Roberts Citation1996). Following Groenendijk and Stokhof (Citation1984, Citation1989), we can think of questions as partitioning possible words into sets, such that the answer to the question is the same within a given partition. For instance, if I ask what is for tea, then I impose a partition on logical space which divides possible worlds into sets, grouped by what I eat for tea in those worlds: a set in which I have fish fingers, a set in which I have spaghetti, and so on. Something answers the question if it helps locate us within that partition of possible space. As Craige Roberts puts it ‘a question sets up a partition on the context set at the point of utterance, each cell the set of worlds in which one complete answer to the question is true’ (Citation1996, 5). If you say we’re having fish fingers, I know where within that partition we are located. If instead you tell me about the novel you are reading you fail to locate us within the relevant partition, and so your contribution is irrelevant to the question I have asked: I am no further on with the task of locating myself within the partition.Footnote19

How do we apply this framework to search engines? It dovetails nicely with the claim made in Section 1 that we can understand inquiries to search engines as nested questions, questions about where to find information that answers a further question. An inquiry to a search engine asks for web pages that will most efficiently let us position ourselves within a partition of possible space, that which is generated by the nested question which is under investigation. A search engine’s goal is to order results in terms of relevance to that question. So the results should be ordered by the efficiency with which they allow us to position ourselves in logical space.

Consider a search for ‘how to cook devilled eggs’. This can be read as a nested question: ‘where can I find information about [how to cook devilled eggs]’. A satisfactory ordering of webpages will prioritise those webpages which maximally efficiently locate the user within logical space relative to the partition imposed by the question ‘how to cook devilled eggs’. What about more diffuse inquiries like ‘devilled eggs’ simpliciter? In this case, the search can be interpreted as a nested inquiry over a set of questions: ‘where can I find information about [how to cook devilled eggs / what are devilled eggs / where did devilled eggs originate / why devilled eggs are called devilled eggs] and a successful ordering of webpages prioritises those that best answer a spread of those questions, perhaps weighted by the centrality or likelihood that that is the question being asked.

6. Epistemic evaluation: informational accessibility and inquiry

To recap, then: I claim that an epistemically good search engine offers the most relevant results to a query, where relevance is understood in terms of the extent to which those results narrow down the space within the partition imposed by the user’s question. A good search engine can do this flexibly for a range of different inquiries.

But I have said nothing so far about how we should evaluate the search engine’s first task: the identification of the user’s question. Our evaluation in terms of relevance relies on the identification of a question that imposes the partition against which we can assess the selected results. Without a standard against which to assess that identification, our evaluation is entirely toothless: if we retrospectively infer the question from the results, any set of results will provide an optimal answer. If it is reasonable for the search engine to interpret Noble’s inquiry as a search for sexualised information, then it does a fine job of responding to it. The question then becomes why and in virtue of what such an interpretation is unreasonable. Why shouldn’t the search engine interpret the search as for pornography? In many searches, it is ambiguous what question is being asked. We need, then, a means of assessing the first task the search engine performs, the disambiguation of the question or set of questions the user is pursuing, and the partition of logical space that imposes. Relative to what set of norms does this assessment take place?

To move towards an answer to this question, we need to consider the perlocutionary effects of the disambiguation of a question. The interpretation of a question imposes a partition on logical space, which foregrounds some distinctions and backgrounds others (Yalcin Citation2018). This has the scope to change both how significant and how accessible information is in the local context of the conversation, and in the global context that serves as background to other potential conversations. As a result, the partition skews both the interpretation of, and the future search for information. Once you have asked what’s for tea, I am under some kind of conversational obligation to find and offer information that answers that question, if I am to qualify as a tolerably cooperative conversational participant. The questions I ask determine which conversational contributions are cooperative, and which are not. That in turns skews the interpretation of novel information: my ambiguous utterance that the freezer isn’t working currently, which relative to another question might be interpreted as implying that we need to fix it, will instead be taken to imply that foods we normally store in the freezer are off the menu. As a result, the introduction of a question has wide-ranging effects on the information that a subsequent utterance is able to convey.

Eric Swanson describes a related phenomenon whereby utterances can influence the likelihood of ending up with one common ground rather than another by deploying one system of categorisation rather than another. In this way, utterances are ‘channels for common ground.’ For instance

our convention of using ‘green’ and ‘blue’ as opposed to ‘grue’ and ‘bleen’ positively causally influences the probability that our discourses’ common grounds distinguish between green and blue things, and negatively causally influences the probability that our discourses’ common grounds distinguish between grue and bleen things. Put metaphorically, our discourse deepens the ‘green’ /‘blue’ channels of common ground. (Swanson Citation2022, 3)

How I disambiguate a question has broad ramifications, then, for the distinctions and information which are salient to me and my interlocutors in that moment. Moreover, repeatedly pursuing certain topics of inquiry has the effect of rendering information that is generally relevant to the questions that constitute those inquiries accessible. If what is for dinner is the question at the forefront of everyone’s minds from 4 pm onwards (and in some households it is), then information that can resolve that inquiry becomes more accessible even when it is not under active consideration. In the long-term, practices of question-asking calcify the relative accessibility of certain information.

We can think of this in terms of accessibility relations between pieces of information: how much cognitive effort would one need to expend to access a given piece of information? Repeatedly inquiring into what is for dinner makes information capable of resolving that question more accessible, that is, accessible with less cognitive effort, even when one is not currently being asked that particular question. It enjoys a kind of standing priority within the mind. The relative effort of accessing information will depend on facts about the cognitive architecture of the individual, and their idiosyncratic concerns, but also on facts about their social, physical and linguistic environment, since that primes certain pieces of information, establishes common associations through repeated exposure and influences the valence and value of information.

With this framework in hand, we can precisify the impact of asking questions on the topics we inquire into. The questions we ask alter accessibility relations, through the repeated imposition of a partition on logical space that foregrounds some distinctions whilst backgrounding others. Crucially for our purposes, the repeated disambiguation of ambiguous inquiries makes a special contribution here. An ambiguous inquiry is a choice-point – it allows for multiple partitions, which will differently affect the accessibility of information. If such inquiries are repeatedly disambiguated in the same way, that entrenches the accessibility of information relevant to the resulting partition. For instance, if I ask ‘are the tiger cubs safe?’ my question is ambiguous between asking whether the tiger cubs pose a danger to others, and whether they are at risk themselves. Repeatedly disambiguating this question to favour the second interpretation over the first makes information about their safe-keeping and health more accessible than information about how to mitigate the risks they may themselves pose.

This gives us a framework within which we can begin to assess search engines’ interpretation of users’ inquiries. That process of interpretation changes the relative accessibility and salience of information, not just at the local level of the search itself, but, through frequent iteration, at the global level that extends beyond that individual search to influence the accessibility of information at large. But what is the further significance of that? Why does the accessibility of information matter?

It matters for three reasons. In the first place, how accessible information is to us determines what we are in a position to know, and in this respect it has an immediate, epistemic impact. In the second place, the accessibility of information, or the salience of properties associated with topics or categories changes our understanding of the nature of those categories through its impact on what the core, essential features are that we attribute to them. Finally, and through this second mechanism, it changes what we perceive as mattering about a particular category, that is, the importance or value we place on certain sorts of information about it. I will say more about each of these and explain how this gives us the foundations (but only the foundations) of an evaluative foothold on search engines.

Inevitably, for cognitively limited creatures the accessibility of some information comes at the cost of the inaccessibility of other information. Nonetheless, we can recognise that not all search engines are created equal in how accessible they render a range of information. We could think of a search engine as a little like a transport system through a metropolis: some transport systems systematically neglect certain locations. They make it very hard to get to them at all, though they may be highly efficient at facilitating access to other areas of the city. These transport systems are, all other things being equal, less good than transport systems that facilitate access to all parts of the city equally well. Of course, other things are generally not equal: there may be excellent practical reasons for designing a transport system that neglects some areas and facilitates access to others. But we can still recognise that in this respect, that transport system is less good than one which facilitates access to all areas of the city equally. Similarly, we could score search engines on how much information they render accessible. Part of what has gone wrong in the Noble case is that the search engine reveals that it makes it very difficult to access non-sexualised information about black girls. This negatively impacts on its accessibility score, relative to a search engine that disambiguates inquiries in such a way that it brings up sexualised information in response to terms which specifically elicit it, but avoids disambiguating the search term ‘black girls’ as invariably seeking out such information.

Search engine algorithms with low accessibility scores are, by and large, epistemically worse than those with higher scores. Why? It is well established that many search engines tend to suppress minority interests and weed out antagonistic perspectives, via the algorithms that drive them which rely on mass interest in sites as a measure of their significance (Diaz Citation2008; Gerhart Citation2004). By rendering a more limited range of information available, a search engine limits what is users are in a position to know. This will naturally impact on subjects’ abilities to satisfy a range of epistemic norms: they may be less able to gain knowledge, more likely to form false or unjustified beliefs on certain topics.Footnote20 At a chronic level, it can negatively impact on the cognitive flexibility of users of search engines, that is, their ability to reliably form true beliefs across a wide range of different topics and tasks, not just because it renders some information less accessible, but because it may give them less practice at the cognitive skills which support flexible knowledge acquisition.

But the implications of what information is rendered more or less accessible go beyond the straightforwardly epistemic. Given that accessibility is a nil-sum game, information is appropriately accessible to us when it matters to us. True beliefs are cheap, if you’re happy to form them about anything at all: you could form a continuous string of them just by recognising the passing of each second. True beliefs come at a price when they are the true beliefs we value. We take pains to render salient information which we value, and our disambiguation of one another’s questions reflects that value schema. I assume when you ask about the flu that you mean the flu in humans because we generally care more about that than we do the flu in other animals. And my disambiguation of your question in turn tells you something about what I value. The same holds of search engines: by resolving the ambiguity in the search ‘black girls’ the engine implies something about what society values: that it places a premium on the sexual properties of black women, that it values them in that capacity, disregarding other properties they may have. In general, the accessibility of information reflects its value to us. By changing how accessible information is, particularly by doing so consistently, search engines imply, at least, a change in its value or significance.

The implication of the disambiguation of a search, that the information provided matters most can be self-fulfilling. It is plausible that many social kinds are cluster concepts, loosely associated with a weighted set of characteristics.Footnote21 Even if there are necessary and sufficient conditions on what it takes to be a white man, for instance, in addition, there are a host of properties that are associated with that category, and possession of which marks out paradigmatic instances of the kind. The relative accessibility of those different properties reflects their centrality to that concept. These conceptual associations are unstable: both the characteristics and their relative weighting are in flux. What role does informational accessibility play here? The accessibility of certain properties roughly reflects their centrality to the concept. When repeated sufficiently, that process of prioritising some information about a particular category over other information has the capacity to itself alter the nature of the category in question. The priority we give to recipes for eggs over other information about them entrenches their status as a thing that is eaten. This is particularly true of human kinds, in virtue of their instability and susceptibility to looping effects (Hacking Citation1995). If a search engine makes some subset of information about a demographic group systematically more accessible than other information, it has the scope to change the weighting in the cluster of concepts that are associated with that kind: black girls has the potential to become, in dominant social use at least, a predominantly sexual category. This is particularly the case given that users are poorly placed to know what information is missing from the results that are returned to them.Footnote22 We often use search engines precisely when we are ignorant about a topic. That ignorance renders us particularly susceptible to the influence of search engines on the underlying conceptual categories into which we inquire. The point here is that the problem is not just one of access to information about a topic: the topic is not fixed or stable prior to the investigation, but is itself created by the repeated act of investigation. Nor is the problem that minority groups find it hard to access the information they want (though as Introna and Nissenbaum describe, this is undoubtedly a problem (Citation2000)): the problem is that majority groups need access to information about minority topics, not just for their own epistemic benefits, though those are real, but because broader social access to information partially constitutes the categories under investigation.

Inquiry is an activity geared towards securing information we value. Through the role they play in disambiguating and facilitating users’ search for information, search engines offer tacit instruction in what information matters about a given topic. In interpreting the terms ‘devilled eggs’ as a search for recipes, the search engine generates the implication that the key feature of devilled eggs is their status as a food. And when the search engine interprets the terms ‘black girls’ as a request for pornographic results, it implies that the partition of logical space which best reflects our values and the nature of the underlying category is one that prioritises sexual information about black women. Indeed, sometimes with very general searches, this may be the implicit or explicit purpose of the search. We do not know what distinctions are relevant to a given topic and we can use search engines to retrofit the questions we might be asking to the results it generates.

This is the point at which we have reached the limits of epistemic evaluation: it cannot tell us what ends we should care about, nor how we should jointly construct the social kinds that define us. We can and should subject search engines to epistemic evaluation. But the way in which search engines play a role in actively directing our search, through a process of disambiguating our questions, means that they are in addition playing a role in shaping our values, and even our underlying categories. And that is inevitable, because an epistemic feature – how accessible information is – both plays a role in constituting various social categories and reflects our broader value system. Search engines shape the collective imagination and the categories it operates on in a way that is not extra-epistemic, but that occurs through a core epistemic feature: the relative accessibility of information.

7. Conclusion

Let me recap the framework I have outlined here: search engines perform a two-stage task: they must disambiguate a user’s inquiry, and then respond to that inquiry with an ordered set of results. There are ethical, practical and epistemic dimensions to both of these stages. I have argued in particular that we can submit a search engine to a form of user-independent, epistemic evaluation relative to a standard of relevance to the question in hand, understood in terms of the efficiency with which the results narrow down the space of possibilities within a partition imposed by the question the user asks.

However, this leaves the question of how we evaluate the search engine’s disambiguation of an inquiry. Here, the picture is much messier. The imposition of a particular partition of logical space has ramifications for the accessibility of information. This is an epistemic feature and it impacts various epistemic indices, but it also has a much wider scope than this, changing what information matters and the nature of the categories into which we inquire. To properly assess the performance of this task, we will need to appeal to a range of epistemic, practical, and ethical norms in a way that is sensitive to the richness of the connections between them, to the way in which the accessibility of information itself has epistemic and practical ramifications.

In developing an account of how we subject search engines to a form of epistemic evaluation, we find that search engines do not just answer questions, but play a much wider role in guiding our practices of inquiry, in a way that is richly value laden. Search engines have the potential to shape our vision of ourselves and others in our society, to both restrict and expand our ability to understand others, and to see the range of ways that they could be.

With this framework in hand, we are in a better position to begin to reintroduce some of the complications that this piece has abstracted away from: how should we balance the practical benefits of personalisation to individual interests against the loss of cognitive flexibility that can accompany them? And in what ways does the influence of corporate interests on search engines make them epistemically less good tools?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I adopt this use of zetetic to mean pertaining to inquiry from Friedman (Citation2020).

2 I am grateful to Paulina Sliwa for first drawing this kind of usage to my attention.

3 See Noble (Citation2018) for more in-depth discussion of the impact of commercialization on search engines and how that distorts their performance away from simply serving their users.

4 For an alternative, related approach, see Dag Elgesem (Citation2008) who understands the function of search engines as ‘to literally provide a testimony to the user about what information is available and relevant to her query’, in the manner of a witness testifying to a judge (Citation2008, 234). In common with the approach I advocate here Elgesem understands search engine as making ‘the second order claim that the information presents is the most relevant to be found, given the query’ (Citation2008, 238). Thomas Simpson argues that the epistemic role of search engines is that of a surrogate expert (Citation2012, 427). Analogising the relationship between user and search engine to one of testimony or expertise involves treating the search engine as akin to another epistemic agent. Since there are clearly various respects in which search engines are distinct from standard epistemic agents in ways that complicate the extension of these concepts to them, I think it preferable to offer an epistemic evaluation of them which avoids forcing this comparison. We can ask what epistemic norms apply to them without assuming that they have the status of experts, or subjects capable of offering testimony.

5 For a defence of the claim that the relevant measure of search engine success is probabilistic see Maron and Kuhns (Citation1960) and Robertson (Citation1977a).

6 In a parallel move for epistemic evaluation, Richard Heersmink offers a virtue epistemology of the internet, which focuses on the question of how agents can use the internet in an epistemically virtuous fashion, whilst also allowing that search engines themselves have epistemic responsibilities (Heersmink Citation2018).

7 In line with this resistance to excluding search engines themselves from direct evaluation is work that points to the profound integration of human users, search engines, and other technological tools. See Christopher Heintz for the suggestion that ‘search engines together with web-users constitute a distributed cognitive system’ that can be evaluated as a whole (Heintz Citation2006, 388). Judith Simon (Citation2015) also argues for a form of distributed responsibility between various agents and algorithms, on the grounds that these cannot be understood in isolation but only through their connections and interactions with one another.

8 For an interesting and in-depth discussion of how to assign epistemic responsibility for autcompletion by search engines in particular see Miller and Record (Citation2017).

9 This approach is complicated by the fact that users often don’t have particularly clear and determinate intentions when performing a search, or at least not ones that they can access. Even in the absence of clear and determinate accessible intentions the user will likely be able to access a sense of frustration when a search engine performs badly, and their intentions can be inferred, albeit somewhat indeterminately, from which results provide greater satisfaction.

10 Heintz endorses something like this kind of norm: ‘With search engines, the meritocratic ideal takes the form of an isomorphism between SERPs [search engines’ results pages] returned on queries and cognitive worth relativised to the topic expressed by the queries’). But he is quick to allow that the metric of cognitive worth ‘should include a universal measure … cognitive worth has an element that does not depend on people’ (Citation2006, 400).

11 As Elgesem puts it

… if the user gest results that do not seem very relevant, she should not – and probably would not – automatically conclude that the search engine is no good. An alternative interpretation to be considered is that the problem was the formulation of the query. (Elgesem Citation2008, 239)

12 Noble herself draws attention to the legitimating power of search engine results, and the way in which that is supported by the assumption of some sort of democratic mandate, and ignorance of the commercial interests that drive results:

Black women’s representations in Google’s ranking is normalized by virtue of their placement, making it easier for some people to believe that what exists on the page is strictly the result of the fact that more people are looking for Black women in pornography than anything else. This is because the public believes that what rises to the top in search is either the most popular or the most credible or both. (Noble Citation2018, 32)

13 Another question this throws up is whether the significance of search terms which refer to demographic groups should ideally be determined by the interests of non-members and members equally, or whether the interests of members should receive some kind of priority.

14 Work in social choice theory on preference aggregation offers resources for developing this kind of interpersonal comparison, though it equally includes in its legacy evidence of the host of challenges that exist to successfully arriving at such tools (Anshelevich et al. Citation2021).

15 This approach meshes with other work on the harms done to individuals by the relative accessibility of information. See, for instance, Rachel Fraser’s discussion of rape metaphors and how it can be in someone’s interests to have information more or less accessible via inference (Fraser Citation2018), or Ella Whiteley’s discussion of how individuals can be harmed by the relative salience of information about them (Whiteley CitationForthcoming). I return to these themes in Sections 5 and 6.

16 For an alternative approach, see Miller and Record (Citation2013) who argue that beliefs formed on the basis of information filtered by the internet are less justified in virtue of subjects’ failing to meet a responsibility to inquire into whether the information on which they base a judgement is incomplete or biased.

17 Susanna Siegel proposes, in the context of journalism an ‘importance principle’ which says ‘to make salient the things that are important for the public to know about’ (Citation2022, 237). The norm I propose for search engines operates a bit like an importance principle, in so far as it assumes that some information is objectively more important, at least relative to a given inquiry, and should be prioritised by search engines regardless of the idiosyncratic preferences of users. Siegel also notes that journalism is subject to a negative constraint, not to let the news be unduly influenced by advertisers (Citation2022, 242). It is very plausible that a similar negative constraint also applies to search engines. We should not assume too automatic an extension of conclusions about news journalism to search engines, however: Whitney and Simpson (Citation2019) offer various ways in which an analogy between journalism and search engines, sometimes assumed in a legal context, breaks down, at least in the context of free speech.

18 For other appeals to relevance, see Alvin Goldman (Citation1999) who endorses an evaluative approach to search engines grounded in their veritistic value, i.e. the extent to which they are conducive to true beliefs. He suggests assessing a search engine on two axes, which he terms precision and recall, both of which appeal to relevance, but Goldman does not himself unpack what relevance consists in in this context. Thomas Simpson meanwhile suggests that Goldman’s veritistic approach needs to be supplemented with some measure of balance, for instance: ‘search engine’s results are objective when their rank ordering represents a defensible judgement about the relative relevance of available online reports’ (Simpson Citation2012, 434). But again this pushes the ball back to giving an account of what constitutes a defensible judgement of relative relevance.

19 Michaelson, Pepp, and Sterken (Citation2022) propose that journalistic conversations are similarly governed by an objective norm of relevance: there are certain things which individuals, and groups ought to know. Since they allow that group members can be wrong about what they ought to know, this is an objective norm. In a similar manner to the application of this framework to search engines below, they allow that moves in a journalistic conversation serve to make information more accessible (in addition to simply contributing information de novo).

20 This is reflected too in the underlying structure of the internet itself. Albert-Lásló Barabási (Citation2002) describes the way in which the web is structured in such a way that certain pages become ‘hubs’, linked to by many other pages. These hubs are highly accessible, whilst many other pages are much less so, with perhaps as much as three quarters of the material on the web being in effect inaccessible. I am suggesting that search engines shape that underlying structure through determining accessibility, and can themselves be understood and evaluated in terms of the patterns of accessibility they generate.

21 See Stoljar (Citation1995) for an argument that ‘woman’ is a cluster concept for instance.

22 Introna and Nissenbaum write that

… if one is searching for a specific product or service, it may be possible to know in advance how to determine that one has indeed found what one was looking for. When searching for information, however, it is difficult (if not impossible) to make such a conclusive assessment, since the locating of information also serves to inform one about that which one is looking for. (Citation2000, 176)

References

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 1993. Values in Ethics and Economics. Boston, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Anshelevich, Elliot, Aris Filos-Ratsikas, Nisarg Shah, and Alexandros A. Voudouris. 2021. “Distortion in Social Choice Problems: The First 15 Years and Beyond.” ArXiv:2103.00911 [Cs, Econ], March. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.00911.

- Barabási, Albert-László. 2002. Linked: The New Science of Networks. Cambridge. Mass: Perseus.

- Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Medford, MA: Polity.

- Brin, Sergey, and Lawrence Page. 1998. “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine.” Computer Networks and ISDN Systems 30 (1–7): 107–117. doi:10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X.

- Castillo, Carlos. 2019. “Fairness and Transparency in Ranking.” ACM SIGIR Forum 52 (2): 64–71. doi:10.1145/3308774.3308783.

- Cohen, L. Jonathan. 1994. “Some Steps Towards a General Theory of Relevance.” Synthese 101 (2): 171–185. doi:10.1007/BF01064016.

- Diaz, A. 2008. “Through the Google Goggles: Sociopolitical Bias in Search Engine Design.” In Web Search, edited by Amanda Spink, and Michael Zimmer, 11–34. Vol. 14 of Information Science and Knowledge Management. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-75829-7_2.

- Elgesem, Dag. 2008. “Search Engines and the Public Use of Reason.” Ethics and Information Technology 10 (4): 233–242. doi:10.1007/s10676-008-9177-3.

- Fraser, Rachel Elizabeth. 2018. “The Ethics of Metaphor.” Ethics 128 (4): 728–755. doi:10.1086/697448.

- Friedman, Jane. 2020. “The Epistemic and the Zetetic.” The Philosophical Review 129 (4): 501–536. doi:10.1215/00318108-8540918.

- Gerhart, Susan. 2004. “Do Web Search Engines Suppress Controversy?” First Monday 9 (1). doi:10.5210/fm.v9i1.1111.

- Gesenhues, Amy. 2015. ‘When Google Gets It Wrong: Direct Answers With Debatable, Incorrect & Weird Content’. Search Engline Land, June 27.

- Gibbs, Samuel. 2016. ‘Google Alters Search Autocomplete to Remove “are Jews Evil” Suggestion’. The Guardian, December 5. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/dec/05/Google-alters-search-autocomplete-remove-are-jews-evil-suggestion.

- Goldman, Alvin I. 1999. Knowledge in a Social World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cam/detail.action?docID=3053391.

- Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1984. “‘On the Semantics of Questions and the Pragmatics of Answers’.” In Varieties of Formal Semantics: Proceedings of the Fourth Amsterdam Colloquium, edited by Fred Landman, and Frank Veltman, 143–170. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Groenendijk, Jeroen A.G., and Martin J.B. Stokhof. 1989. “Context and Information in Dynamic Semantics.” In Working Models of Human Perception, edited by Herman Elsendoorn and Ben A. G. Bouma, 457–486. London: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-238050-1.50027-5.

- Hacking, Ian. 1995. “The Looping Effects of Human Kinds.” In Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Debate, edited by Dan Sperber, David Premack, and Ann Premack, 351–394. Clarendon: Oxford University Press.

- Heersmink, Richard. 2018. “A Virtue Epistemology of the Internet: Search Engines, Intellectual Virtues and Education.” Social Epistemology 32 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/02691728.2017.1383530.

- Heintz, Christophe. 2006. “Web Search Engines and Distributed Assessment Systems.” Pragmatics & Cognition 14 (2): 387–409. doi:10.1075/pc.14.2.15hei.

- Hinman, Lawrence M. 2005. “Esse Est Indicato in Google: Ethical and Political Issues in Search Engines.” The International Review of Information Ethics 3 (June): 19–25. doi:10.29173/irie345.

- Introna, Lucas D., and Helen Nissenbaum. 2000. “Shaping the Web: Why the Politics of Search Engines Matters.” The Information Society 16 (3): 169–185. doi:10.1080/01972240050133634.

- Maron, M. E., and J. L. Kuhns. 1960. “On Relevance, Probabilistic Indexing and Information Retrieval.” Journal of the ACM 7 (3): 216–244. doi:10.1145/321033.321035.

- Michaelson, Eliot, Jessica Pepp, and Rachel Sterken. 2022. “Relevance-Based Knowledge-Resistance in Public Conversations" .” In Knowledge Resistance in High-Choice Information Environments, edited by Jesper Strömbäck, Åsa Wikforss, Kathrin Glüer, Torun Linholm, and Henrik Oscarsson, 106–127. London: Routledge.

- Miller, Boaz, and Isaac Record. 2013. “Justified Belief in a Digital age: On the Epistemic Implications of Secret Internet Technologies.” Episteme; Rivista Critica Di Storia Delle Scienze Mediche E Biologiche 10 (2): 117–134.

- Miller, Boaz, and Isaac Record. 2017. “Responsible Epistemic Technologies: A Social-Epistemological Analysis of Autocompleted web Search.” New Media & Society 19 (12): 1945–1963.

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press.

- Roberts, Craige. 1996. “Information Structure in Discourse: Towards an Integrated Formal Theory of Pragmatics.” Semantics and Pragmatics 5: 1–69.

- Robertson, S. E. 1977a. “The Probabilistic Character of Relevance.” Information Processing & Management 13 (4): 247–251. doi:10.1016/0306-4573(77)90005-X.

- Robertson, S. E. 1977b. “The Probability Ranking Principle in IR.” Journal of Documentation 33 (4): 294–304. doi:10.1108/eb026647.

- Roth, Lydia. 2019. “How Search Engines Work: Everything You Need to Know To Understand Crawlers.” Alexa Blog (blog). August 7. https://blog.alexa.com/how-search-engines-work/.

- Siegel, Susanna. 2022. “Salience Principles for Democracy.” In Salience, edited by Sophie Archer, 235–266. London: Routledge.

- Simon, Judith. 2015. “Distributed Epistemic Responsibility in a Hyperconnected Era.” In The Onlife Manifesto, edited by Luciano Floridi, 145–159. Cham: Springer.

- Simpson, Thomas W. 2012. “Evaluating Google as an Epistemic Tool.” Metaphilosophy 43 (4): 426–445.

- Sperber, Dan, and Deirdre Wilson. 1994. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Reprint. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Stoljar, Natalie. 1995. “Essence, Identity, and the Concept of Woman.” Philosophical Topics 23 (2): 261–293.

- Swanson, Eric. 2022. “Channels for Common Ground.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 104: 171–185. doi:10.1111/phpr.12741.

- Tavani, Herman. 2005. “Search Engines, Personal Information and the Problem of Privacy in Public.” The International Review of Information Ethics 3: 39–45.

- Tavani, Herman. 2020. “Search Engines and Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Fall 2020. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato-stanford-edu.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/archives/fall2020/entries/ethics-search/.

- Whiteley, Ella. Forthcoming. “Harmful Salience Perspectives.” In Salience, edited by Sophie Archer, 193–213. Routledge.

- Whitney, Heather, and Robert Mark Simpson. 2019. “Search Engines, Free Speech Coverage, and the Limits of Analogical Reasoning.” In Free Speech in the Digital Age, edited by Susan Brison, and Katharine Gelber, 33–41. Oxford: OUP.

- Yalcin, Seth. 2018. “Belief as Question-Sensitive.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 97 (1): 23–47. doi:10.1111/phpr.2018.97.issue-1.