ABSTRACT

Feminists have always been concerned with how the clothes women wear can reinforce and reproduce gender hierarchy. However, they have strongly disagreed about what to do in response: some have suggested that the key to feminist liberation is to stop caring about how one dresses; others have replied that the solution is to give women increased choices. In this paper, we argue that neither of these dominant approaches is satisfactory and that, ultimately, they have led to an impasse that pervades the contemporary feminist debate. The problem is that both sides of the debate understand women’s complicity in patriarchal subordination as a matter of what women wear and do. Instead, we propose a phenomenological analysis that understands complicity as based in our relations to our clothes. Starting from this phenomenological perspective, we sketch a new relational feminist ethics of dressing. This alternative ethical paradigm cannot yield a simple recipe for how to dress or tell us what garments are off-limits. But it can offer a way to make critical feminist judgements about clothes without veering into a stifling new prescriptivism.

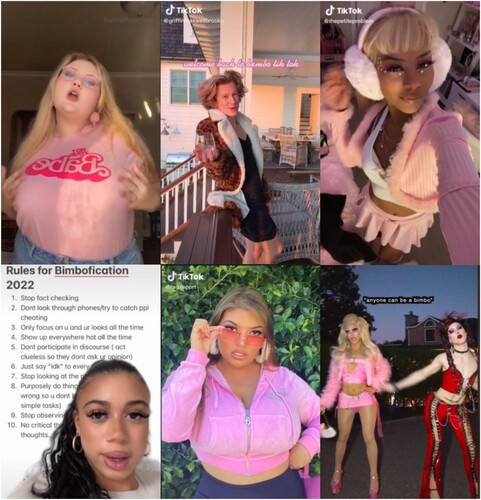

Pink, tight-fitting clothes, exposed thongs, Playboy logos and glitter embellishments – these are some of the key elements of ‘bimbocore’ (Le Citation2022, ). Popularised on TikTok, this ‘aesthetic’ embraces the bimbo ideal of the early 2000s, embodied by the likes of Paris Hilton or Britney Spears: a ‘girly girl’ who may be unintelligent and frivolous but who is ‘perfectly manicured, with all the latest beauty and fashion trends mastered’ (Reilly Citation2022; see also Chrissy Citation2020; GMB 2020; Rag Report Citation2021; Fifi Citation2021; Princess Citation2020).Footnote1 Bimbocore seems to be exactly what feminists have critiqued for centuries: restrictive and oversexualising clothes, an obsession with appearance, and a narcissistic revelling ‘in simply existing as a woman in the world with a body on display’ (Haigney Citation2022). But these ‘new bimbos’ have been hailed by feminist commentators as liberated dressers, reacting against a decade of misguided ‘girlbosses’ in work-ready pant suits and ‘low-maintenance cool girls’ who had tried to escape the power of the male gaze through a sartorial ‘low-effort ethos’.Footnote2 To those who insist that bimbocore oversexualises and objectifies, the new bimbos respond: ‘to insinuate that self-expression is always a form of pandering is reductive and useless’ (Griffin Maxwell Brooks in Morgan Citation2022). Embracing bimbocore is about ‘let[ting] girls do what they want; [because] we earned it’ (Becca Moore in Reilly Citation2022).

Figure 1. Bimbocore on TikTok (Le Citation2022).

Bimbocore illustrates the state of contemporary feminist debates around clothing. The issue is not just that subordinating garments or norms are imposed on women. To the extent that women like the new bimbos adopt these items of clothing and these practices of dressing, dress can become a site of what Beauvoir termed women’s ‘deep complicity’ with patriarchal power (Beauvoir Citation(1949) 2011, hereafter ‘TSS’: 10): an area of life in which women actively support, reinforce, and perpetuate oppressive gender hierarchies. But in criticising women’s choices as complicit, are we adopting the ‘cool girl’ stance that restricts women’s self-expression, ‘trades too freely on notions of self-deception’ (Srinivasan Citation2021, 82), and may even be a sign of ‘internalised misogyny’ (Reilly Citation2022)? Or should we remember that ‘[t]he mere fact that women participate in misogynistic beauty practices … does not place such behaviours – or the norms that dictate them – beyond scrutiny’ (Khader Citation2012, 302)? These issues are not just problems for ‘other women’. The cool girls and the new bimbos may sit at two extremes of the sartorial spectrum, but the problem of clothes and complicity they bring to light is one that we all face in more or less explicit ways every day. And it is an issue on which contemporary feminism is stuck. If the ‘low maintenance’ approach seems restrictive and untenable, the ‘be yourself’ spirit of the new bimbos means there is nothing critical we can say about clothing choices.

In this paper we aim to move past this impasse. We ask: how should we dress, if we are to avoid upholding, reinforcing or being complicit in our own subordination? After outlining the two major feminist critiques of women’s clothing – objectification and excessive care – we distinguish two dominant camps in the literature: ‘opt out’ theorists, who suggest that the key to liberation is to stop caring about how one dresses; and ‘choice as liberation’ theorists, who suggest that the solution is to give women increased choice over what to wear. We argue that ultimately these two ways of thinking have driven the current debate to an impasse because of their simplistic understandings of social agency and social meaning. To overcome this, we turn to the phenomenological tradition and propose to shift the focus from actions and choices to relations. We argue that the problem lies not in what we decide to wear, but in the misguided ways we can take clothes to be meaningful; and not in how much we care about our clothes, but in the dominating kind of care we often have for our clothing. This approach enables us to develop a picture of complicity as constituted not by an action, but by a specific relation to oneself, others, clothing, and the social world. Finally, in line with this relational account of complicity, we sketch a new feminist ethics of dress that can do better than ‘opting out’ and ‘choice as liberation’. On this approach, no garments are on or off limits, and there is no right amount of time and care we should spend on clothes. But equally, not all garments, styles and routines are compatible with ethical dress. Our phenomenological approach to clothes and complicity enables a critical analysis of the new bimbos, whilst avoiding the pitfalls of the low maintenance cool-girl. But more importantly, it gives us the tools to critically reflect on our own practices. Clothes are a rich, nuanced and complex area of our daily lives where larger issues of complicity, domination and choice play out. Examining these issues within the microcosm of clothes may not only help us to understand how to dress, it may also tell us something about how to live.

1. Clothes as a site of women’s complicity in patriarchy

Feminist thinkers have historically seen clothing as central to the creation of patriarchal social relations in two interrelated ways: by focusing on the clothes women wear, and the care women devote to their clothes. Firstly, feminists have emphasised that feminine dress contributes to subordination through various forms of sexual objectification.Footnote3 Stiletto heels make women weak and fragile, short skirts and plunging necklines oversexualise them, and embellished fabrics cast women as treasures to be possessed. Simone de Beauvoir, observes that feminine clothes do not aid women in living in the world but rather offer women ‘as a prey to male desires’:

… fashion does not serve to fulfil her projects but on the contrary to thwart them. … the least practical dresses and high heels, the most fragile hats and stockings, are the most elegant; whether the outfit disguises, deforms, or moulds the body, in any case, it delivers it to view. (TSS: 572)

The second strand of feminist critique focuses on the damaging effects of women’s excessive attention to dress, regardless of what garments they put on. Mary Wollstonecraft, for instance, saw in women’s care for their clothes an ‘employment [that] contracts their faculties more than any other that could have been chosen for them, by confining their thoughts to their persons’. In ‘making caps, bonnets, and the whole mischief of trimmings, not to mention shopping, bargain-hunting, etc.’, women place the energy that should be directed towards the world at the service of a vain self-regard and hollow self-improvement ( (Citation1792) 2008, 147). This distorts women’s ethical character, encourages intellectual shallowness, and a lack of practical wisdom ((Citation1792) 2008, 147–150, 274–277). Feminist theorists have argued that women’s attention to clothes is also a real ‘servitude’ (TSS: 577): an addiction that is ‘timewasting, expensive and painful to self-esteem’ (Jeffreys Citation2005, 6). The rapid pace of contemporary fashion trends ‘means that we bankrupt our finances’ (Baumgardner Citation2011, x) just trying to keep up and often accept economic dependence to support our clothing habits (TSS: 614, 681). Picking out clothing each morning is for many women a draining form of ‘emotional labor’ (Radke Citation2018): it requires starting out one’s day by noticing flaws, inadequacies, and by measuring ourselves against impossible expectations, leading to a ‘permanent posture of disapproval’ and a relentless pursuit of self-correction (Bartky Citation1990, 40). Women’s ‘immoderate fondness of dress’ (Wollstonecraft (Citation1792) 2008, 252) results then in a form of patriarchal ‘discipline’ of women’s bodies and minds (Bartky Citation1990, 70).

The critiques levelled at women’s clothing are not simply objections to the imposition of unequal and subordinating gender norms. It is true that there are regulations and penalties at work in feminine dress and that the same care, attention, and objectifying standards are not demanded of men.Footnote4 But it is women themselves, often under the dismissive or uninterested eyes of men, that cherish fashion, shopping, and dressing up. Although sexist norms apply pressure, women’s behaviour is far from mere self-protection or passive acquiescence. For instance, the look of the ‘[B]imbo 2.0 is perceived as a choice’ by those who adopt it (Linton Citation2022). Indeed, the new bimbos are mostly taking their cues from the self-generated content of other women on TikTok – ‘[t]his is hyperfemininity by and for girly girls’, they say (Reilly Citation2022). As many feminist commentators have noted when writing about contemporary women’s choice of objectified and objectifying clothing, this ‘is not a situation foisted upon women’ (Levy Citation2005, 33). ‘Women are deeply complicit in creating and selling this culture’ (Walter Citation2010, 32). Whether by turning away from more ‘valuable’ and rewarding activities, by engaging in obsessive beauty practices that damage their self-esteem, or by adopting degrading forms of dress, feminist theorists argue that women become complicit in their own subordination by actively constituting themselves into precisely the passive objects society makes them out to be.Footnote5

1.1. Overcoming complicity: ‘Opting out’

Given this diagnosis, what can be done? A natural political response is to harness this activity for resistance. Instead of giving into patriarchal pressure, women should say ‘no’. Call this the ‘opting out’ strategy: women should realise the subordinating function of clothes, opt out of feminine dress and of the care that it demands. Just say no to uncomfortable tight clothing, to fragile fabrics, and to wasting time, money, and effort on keeping up with fashion. Favour practical and functional clothing, demanding minimal thought and attention. This is an ideal embraced as far back as 1792, when Wollstonecraft recommended that, instead of fussing over their clothing, women should wear plainer styles and turn to activities of real value: ‘gardening, experimental philosophy, and literature’ ((Citation1792) 2008, 147). Opting out was also an influential vision within ‘women’s lib and lesbian feminist writings’ of the 1970s (Hillman Citation2013, 161; see also Jeffreys Citation2005, 1). And it continues to be appealing to contemporary activists, like the women of the counter-fashion collective Rational Dress Society whose trademark jumpsuit, available in over 200 sizes, claims to be ‘the open-source, ungendered monogarment to replace all clothes in perpetuity’ (Radke Citation2018; ).

Figure 2. The Jumpsuit by the Rational Dress Society (https://www.jumpsu.it).

This may seem like an insensitive call for women to simply ‘get over it’, but opting out is not an individualistic vision of liberation by sheer willpower. As Sheila Jeffreys points out, in freeing yourself from the shackles of patriarchal limitation, you will also be contributing to a wave of social change, making it easier for other women to do the same (Jeffreys Citation2005, 176).Footnote6 This collective dimension acknowledges and assuages the worry that it will be psychologically hard for individual women to forego their clothes (Bartky Citation1990, 77) and it frames this as both a political project and a way of living better as individual women.

And yet, opting out has largely been a historical failure. It is true that clothing norms have changed greatly since the mid-twentieth century, but many of Wollstonecraft’s worries about feminine clothing remain well-founded – oversexualisation, impracticality, and the race to keep up with the trends. Although the option to ‘not care’ is more accessible than ever before, by and large, women have not taken it up, as the rise of bimbocore illustrates. This fact alone, as Heather Widdows points out, should give ‘proponents of the [opting out] position pause for thought’ (Citation2022, 5).

If anything, opting out is now associated with the low-maintenance cool girl stereotype, openly rejected and criticised by young feminists (Reilly Citation2022). Part of this failure stems from the sense that opting out encodes a stifling prescriptivism that constrains rather than liberates. Since one cannot help but make some choice about what to wear, the opting out strategy ends up ‘substituting one restriction for another’ (Hillman Citation2013, 168). ‘[A]t the end of the day, it’s just as oppressive to be told you can’t wear Miucci Prada as it is to be told you must’ (Baumgardner Citation2011, xi). If we are invested in allowing women to be full agents, we should support their ability to choose what to wear as creative, self-fashioning individuals, rather than prescribing a politically correct norm like the one that emerged among opt out feminists of the 1970s: ‘jeans, button-down work shirts, and work boots, often without makeup and bras, and sometimes with short hair’ (Hillman Citation2013, 162; see also Radcliffe Richards Citation1980, 225–226). Many women at the time objected that there was something decidedly masculinising about this norm (Hillman Citation2013, 167). Similarly, today’s bimbocore fashionistas accuse cool girl feminists who condemn their ‘girly’ clothes of ‘internalized misogyny’ (Reilly Citation2022). In taking masculinity to be the neutral and liberating position, opting out seems to buy into a certain widespread ‘misogynist mythology [that] gloats in its portrayal of women as frivolous body decorators’ (Young Citation2005, 68).

1.2. A response to opting out: ‘Choice as liberation’

For all its promise, opting out seems to deny women’s experience of genuine pleasures and creative self-expression in clothing. It may even perpetuate a misogynistic dismissal of dress as trivial ‘femme frippery’ (Grewal Citation2022, 14). These worries have greatly contributed to the ascension of a competing feminist response: the ideal of ‘choice as liberation’. As early as the 1970s, this alternative strategy has told women that the way to overcome subordination is to increase options (Hillman Citation2013, 167). No clothing norms of dress and care should be imposed on women, by either patriarchal or feminist forces – to be free is to wear what you want. This has arguably become the dominant line within contemporary post-feminism (Hillman Citation2013, 176). We see it articulated in the ethos of the new bimbos – ‘You are hot – wear what you want’ (Grimes Citation2022) – and in their commitment to making sure that TikTok ‘creators of all different races, sizes, abilities, genders, and sexualities [can embrace] the bimbo trend’ (Brooks in Morgan: Citation2022, ). We also see a similar thought in the words of feminist influencers like Florence Given:

It’s really powerful to use your appearance to control the way people perceive you. And whether that’s through dressing in baggy clothes or showing off skin or doing whatever you want, do it for you and do it because you want to. (The Sunday Times Style Citation2022)

Figure 3. #Bimbotok creators (GMB Citation2020; Sugar & Spice Citation2021; Rag Report Citation2021; Jennifer Citation2022; Fifi Citation2021).

Choice as liberation allows women to embrace the pleasures and creative potential of clothing. But it does so only by ignoring the diagnosis that motivated opting out in the first place. The problem identified by critics like Wollstonecraft and Beauvoir was not merely that women had to dress in a certain way. The issue was also women’s complicity: how women voluntarily reinforce or contribute to their own subordination through the choices they make and the practices they adopt. This is a much knottier problem because it is not simply a function of limitation and, therefore, will not necessarily be resolved by expanding women’s options (Knowles Citation2022; Melo Lopes Citationforthcoming). Choice as liberation effectively changes the conversation from one about complicity to one about top-down imposition. Theoretically, choice as liberation ends up embracing the idea that the ‘right’ clothing for women is what resonates with a pre-social, ethically uncompromised self, and its deep preferences. This is a naïve picture of agency that has been thoroughly rejected by feminist theorists (Butler Citation1990; Chambers Citation2008, 21–44; see also Grewal Citation2022, 30, 56). Politically, this attitude risks silencing all criticism of women’s clothing habits, effectively ‘privatizing’ ethical evaluation (Widdows Citation2013, 166) and allowing women to ‘return to traditional styles without fully realizing the political consequences’ (Hillman Citation2013, 169). After all, whatever a woman chooses is ok ‘because she wants to’, to cite Given. But what if women choose to spend hours shopping for cripplingly high heels and skin-tight ‘club wear’, like the proponents of bimbocore? Or if they blow a fortune on bone-crushing corsets and constricting waist-trainers? Under choice as liberation these become unassailable personal likings that cannot be subjected to critical examination.

Feminist philosophy thus finds itself at an impasse when it comes to clothes.Footnote8 Opting out flowed naturally from a sophisticated analysis of the way in which women’s choices contribute to gender hierarchy. However, it failed to understand the complexity of what dress is and can be and risked instituting a new prescriptivism driven by potentially misogynistic norms. Reverting to a view of clothes as morally good insofar as they are chosen seems tempting, but it fails to address the problem of complicity. It relies on an implausible theory of the self, and risks silencing important criticism. The result is that there seems to be little that feminists can say about dress today without becoming low maintenance cool girls or new age bimbos. To move forward, we need to change the terms of the debate. We want to suggest that it was the initial casting of the problem of complicity as a matter of what women do – what they wear, or how much time and money they spend – that set feminists on the wrong track. Focusing on choices and actions sets us up for an impossible task of drawing clear and general lines in one of the most complex, nuanced, and rich areas of our daily lives. What is needed then is a different approach that reflects fundamentally not on our wardrobe, but on how we relate to its contents. A philosophical methodology that enables us to do this is phenomenology.

2. Clothes and complicity: towards a phenomenological analysis

For phenomenology, ‘the relation is the primary thing’ (Gadamer (Citation1975) 2004, 241). In the context of clothes and complicity, beginning from a relational phenomenological perspective means taking a step back from the current debates over whether the push-up bra, the short skirt or the bimbocore aesthetic are in themselves oppressive or freeing. It means rejecting an atomistic approach to agents and items of clothing, and instead focusing on the broader relations in which we and our clothes always stand. This is not only to conceive of us as nodes in a relational network, but to endorse the phenomenological view that what we are – and what all entities are – are the relations in which we are involved (Heidegger Citation(1927) 1962, hereafter ‘BT’: 68, 107–110, 186–188). This allows us to recognise, for example, that a high heel is not appropriate or inappropriate in itself, but that such judgements can only be made with reference to a specific agent in a particular situation with a certain set of possibilities. The high heel may be appropriate for the boardroom, but not for our career as a sky diving instructor. Beginning with a commitment to taking relationality seriously, we return to the two problems the feminist critique of dress identified – excessive care and subordinating clothing – and reframe them. By drawing on the phenomenological tradition, we can see how misguided opting out and choice as liberation theorists were, and offer a way to overcome the impasse they generated.

2.1. Excessive care: a relational approach

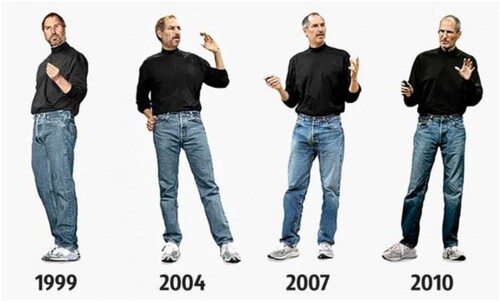

As we have seen, feminist critics object that women spend too much time on their clothes, to which opt out theorists reply: ‘so we should stop caring about our clothes!’ But is this really possible? Clothes are not something optional. From birth we are clothed beings, wrapped in fabric. And, as we get older, we have to make a choice, however minimal, every time we get dressed. Even Steve Jobs, who notoriously spent most of his life wearing the same jeans, black turtleneck and New Balance sneakers, cared about his clothes to the extent that he concerned himself with wearing the same thing every day (; Mac Donnell Citation2022). Moreover, getting dressed, however little time we spend on it, must involve a care for how things are worn, what materials and items of clothing will be suitable or unsuitable for our planned activities, and an awareness of the social norms, scripts and accepted practices that surround dressing. We might have to show a very different type of care when handling an expensive silk scarf, which we put on delicately and store in a special box, from the minimal way we care for clothes worn for painting and decorating, which we leave crumpled on the floor after a hard day’s work. But even unthinkingly throwing on a pair of trousers still involves care, because care – as a ‘type of concern that manipulates things and puts them to use’ (BT: 95) – is what enables us to put the trousers on correctly. If care describes our basic ability to be-in the world and interact with entities, as phenomenologists argue, not caring about clothes is not an option (Gadamer (Citation1975) 2004, 253; BT: 227).

Figure 4. Steve Jobs’ outfit (Mohamed Citation2022).

Even if we pay little heed to issues of dress ourselves, we are still subject to the expectations, perceptions, receptions and reactions of others, which are affected by the clothes we wear and which in turn affect our own worldly possibilities. Consider the example of our French colleague and her experience of taking the agrégation exam, a competitive examination for entrance into the French civil service. On her first attempt she was neatly presented, hair and make-up done, appropriate smart clothes worn. She was happy with her performance and expected to score well. However, she failed because ‘they did not think she was serious enough’. She went back the following year, hair unwashed, no make-up, drab clothes, and passed. Despite no substantial difference in her academic ability between the two tests, she was now deemed to be serious. One might cite this example in support of the opting out strategy, but to do so would be to misinterpret the case. Our colleague did not ‘not care’ when she returned to retake the exam. Rather, she had to affect the appearance of not caring, which was in fact the result of much care. This was a care directed not towards an external expression of her identity and her commitments – which can be a valuable way to relate to clothes (Yim Citation2011). It was a care only directed towards meeting the expectations of others: achieving the correct level of un-washed hair, of getting just the right level of dishevelment so as to be taken seriously.

Just as we cannot opt out of care for our clothes, we cannot opt out of care for others or their care for us, because care in the form of ‘solicitude’ describes the basic way in which human agents are related to one another at an existential level (BT: 158). We are not atomistic, isolated individuals, mushroom men springing up without mother or father (Benhabib Citation1987, 84–85). At an existential level we are always being-with-others (BT: 155), which is to say we are at base relational beings. Others ‘not only help to constitute what we know, they also help to constitute an essential part of who we are, who we were and who we can become’ (Freeman Citation2011, 370). As the agrégation example demonstrates, our colleague’s worldly possibilities – the possibilities that constitute who she is and how she lives her life – are affected by the care others have for her and her appearance, and in turn, the way she has to care for others and herself. Care, then, describes how we relate to entities (BT: 95), how we are with others, bound up with them at an existential level (BT: 158), as well as articulating our distinctive human mode of existence as such (BT: 227).

Although care for others and their care for us is not something we can escape, we can nevertheless draw a phenomenological distinction between ‘dominating’ and ‘liberating’ modes of care (BT: 159). That is, we can distinguish between modes of care where the agent in question is identified solely with what they do, and a mode of care that addresses the agent qua agent, recognising their freedom in a way that they can ‘become free for it’ (BT: 158-159). As the agrégation example suggests, the way in which women are socially directed to care about clothing as women, and in which others are directed to care about our clothing qua women are often dominating modes of care which work to subordinate us. First, by relying on a patriarchal understanding of women as fundamentally things to be looked at, this form of care both heightens the stakes of dress and makes it unimportant as an achievement: ‘as woman is an object, it is obvious that how she is adorned and dressed affects her intrinsic value’ (TSS: 577). Not paying sufficient attention to appearance becomes not just carelessness, but a pathological transgression – think Andrea Dworkin. And yet, being seen to make an effort only confirms one’s value as an object, not as a socio-political actor – think Gloria Steinem.Footnote9

Second, norms of feminine dress demand a precarious compromise between sexualisation and ‘modesty’ that is impossible to achieve (TSS: 574). This dominating care for dress systematically creates what Marilyn Frye terms a ‘double bind’: a situation ‘in which options are reduced to a very few and all of them expose one to penalty, censure or deprivation’ (Frye Citation1983, 2). Wearing the same faded overalls every day makes you pathological, but a trendy wardrobe can only confirm you are really a decorative object. Looking sexy is integral to being unremarkable. But achieving that illusive ‘compromise between exhibitionism and modesty’ requires time, money, and energy and never leads to sure results (TSS: 574; see also Wolf (Citation1990) 2002, 290). In sum, the kind of care that patriarchal expectations impose on women makes clothing a losing game.

What the phenomenological perspective reveals is that the problem with practices of dressing is not the amount of care women put into their clothes, but how women are made to care about dress in dominating ways: in ways that always work to confer on them the subordinate status of a primarily aesthetic object or that of a relative being, never that of an agent in their own right. This phenomenological analysis that can both critique dominating care, whilst observing that care is an inevitable feature of our relation with clothes, gives us an extra reason to reject opting out. But it also suggests new positive ways to think about practices of dressing. It suggests that it is important for others, including men, to care differently about how women look. Given the relational nature of our existence, it is everyone’s responsibility to create different worldly possibilities. And it also makes clear that, to avoid being complicit in our own subordination, women themselves need to ask questions about which ways of caring are characterised by subordination and domination; and which practices of care can be liberating and open up new possibilities that may help to loosen the bonds of gender injustice. It is therefore crucial not to lose sight of what opt out theorists got right: even if we cannot help but care, the kind of patriarchal care that dominates many contemporary relations to clothes is not inevitable and depends on women’s active role in sustaining it. There are ways of thinking and wearing clothes that are not simply reactions to double binds, but that are nevertheless still possible in our non-ideal world. In other words, there is more to clothes and fashion than grey jumpsuits and pink latex dresses.

2.2. Objectifying clothing: a relational approach

But what of the feminist objection that the problem is not just the attention women dedicate to their clothing, but the very clothes they wear? As we have seen, the choice as liberation response is to suggest that as long as the clothes are chosen, there is no issue. This commitment is reflected in the bimbocore ethos, where what used to be seen as objectifying and ‘ditsy’ modes of self-presentation are now heralded as practices of ‘self-love and new wave feminism’ because they are chosen out of many viable options (Linton Citation2022). But is this project of ‘feminist reclamation’ really so straightforward?

Another important insight we draw from the phenomenological literature is the idea that meaning itself is relational. Meaning is not out in the world existing independently from us, simply to be grasped or discovered, but equally we do not project meaning onto the world. Rather meaning is constituted in the relation between us and the world (Knowles Citation2013). The meaning of our clothes is dependent on a network of references to other items of clothing, to us, to other agents, and to the social context in which they exist. In saying that it is in virtue of women’s choice that a corset becomes ‘liberating’ rather than ‘oppressive’, or that a high heel comes to signify strength rather than fragility, choice as liberation strategists ignore how meaning works.

In fact, it is our world that enables entities, ways of life, practices, and our choices to show up to us in the meaningful ways that they do (BT: 97-100). Worlds act as the backdrop to – and enable our engagement with – entities, our relations with others, our understanding of ourselves and our comportment in general. We can occupy multiple worlds at the same time because worlds are not necessarily physically delineated: they are primarily meaningful contexts (BT: 94). We can exist in the world of fashion, the world of the university and the world of global patriarchy all at once. The relations of significance that make up these worlds shape the ways in which the entities, choices, situations, and agents we encounter show up to us as meaningful (BT: 98-99). For example, the choice of many women today to wear shapewear only makes sense in a context where women’s bodies are hyper-visible in athleisure ‘yoga pants’ and bodycon party dresses, where social ideals emphasise control over one’s body (through dieting or waist-training, for example), and where off-the-rack clothing and set sizes are the norm. To understand complicity, we must focus then not only on what is chosen, but on how certain choices come to appear to us as meaningful.

Within this wider relational perspective, we can see that meaning change is not dependent on our choices and intentions alone (Melo Lopes Citation2019, 2525). It depends on the way we engage with items of clothing, how we combine them, and the relations in which they stand to each other, to ourselves, to others and to our social context. For example, hotpants paired with a crop top and high heels worn by a conventionally beautiful Daisy Duke-type figure, waitressing tables in an American bar do seem to mean something different than when they are worn by a plus-sized woman with a baggy T-shirt and sneakers walking casually down the street (). Meaning is not totally malleable – you cannot wear hotpants and be ready for the office – but there is still a sense in which the same garment can signify different things. In the case of Daisy Duke, the ‘short shorts’ seem to work to reproduce a recognisable script of glamourized oversexualisation and to ‘deliver [the body] to view’ for paying customers (TSS: 572). By contrast, in the second instance, the hotpants seem to signify a commitment to body-positivity and an attempt to subvert dominant social scripts about the types of bodies that should be on public display. The difference cannot be attributed simply to intention, body, setting or styling, but is rather a product of all of these things together, redefining the network of relations through which the hotpants appear as meaningful. What matters for non-complicit dressing is thus not simply what clothes women wear because garments can have different meanings. And while choice theorists were right to point to women’s creative agency as an important element in overcoming complicity, intentions are not the central factor determining whether a garment objectifies or subordinates. They are just one aspect of the larger web of relations that constitutes the meaning of our clothes.

Figure 5. Left: Jessica Simpson as Daisy Duke in ‘The Dukes of Hazard’ 2005 (Ritschel Citation2020); Right: ‘9 Ways To Wear Plus-Size Shorts This Summer’ (Dalessandro Citation2015).

2.3. A relational analysis of clothes and complicity

By addressing the issue of clothes and complicity through a phenomenological lens we are furnished with additional reasons why choice as liberation and opting out fail. But the phenomenological perspective also enables us to see that behind both strategies there lies a common problem. Both views rely on simplistic understandings of our social agency and, consequently, on an unsatisfying analysis of the phenomenon of complicity. Opting out and choice as liberation both see complicity as fundamentally a matter of what women do or don’t do: of what they choose to wear, of how much moneythey spend on their clothes, and of how much time and attentionthey dedicate to their wardrobe. However, if we take seriously the relational nature of human existence, complicity cannot be understood in this way. We cannot divorce agents, their choices and actions from the relations and the context in which they play out (BT: 79). To analyse human existence is to begin by focussing on the co-constitutive relation between the agent and the world (BT: 82-83): ‘The relation is the primary thing, and the “poles” into which it unfolds itself are contained within it’ (Gadamer (Citation1975) 2004, 241). Taking this insight on board means approaching complicity, fundamentally, as a matter of how we relate to the world.

Our aim, then, should not be to generate an exhaustive list of what does or does not count as complicity. This project is doomed to failure, owing to the nuanced, complex, flexible, and shifting network of relations that constitute the way clothes and practices of dressing become meaningful. Rather, our aim as feminists should be to develop a detailed analysis of the quality of the relation the agent has to their social world, to their clothes and to themselves: asking whether this relation is one of openness and liberation; or subordination and complicity. This phenomenological approach cannot offer us a full-blown manual for how to dress – it is a deliberate eschewing of that action-focused project. But it can offer us the critical tools to relate in better ways to our wardrobes.

3. A feminist ethics of non-complicit dressing

Our aim in this final section is to articulate a positive ethics of feminist dress in line with our relational analysis of complicity. In evaluating an agent’s relation to their clothes, the notion of freedom is key. But freedom here is not simply a freedom of choice, nor a freedom from norms, as the choice as liberation and opt out theorists would have it. In rethinking the problem of clothes and complicity through a relational lens, we can see that what is required is a relational understanding of freedom that enables us to appreciate both the limitations of our situations and the possibilities that may exist for subverting and negotiating such limitations. Understanding freedom relationally means characterising it primarily as an active negotiation with the situations into which we are thrown (BT: 331). On this basis, we aim to distinguish complicit relations to our clothes, where we relate to social norms, expectations, and items of clothing as if we had no other option; from non-complicit ones, where we exhibit an awareness of social scripts, norms, and meanings, but recognise that we are not totally bound by them.Footnote10 Moreover, these relations are not primarily ‘intellectual’ or epistemic. Our grasp on our situation does not necessarily reach the level of propositional belief, but is expressed in how we comport ourselves in the world (BT: 200; Knowles Citation2021a, 460).

A relational understanding of freedom takes seriously the way in which we are deeply shaped, constrained and impacted by the (oppressive) social structures, norms, expectations and scripts of our situation. However, at the same time it also recognises that we always exercise some agency in the way we embrace or resist the situations into which we are thrown.Footnote11 Non-complicit ways of relating to the world are then ones in which we recognise and actively take up our freedom in situation – where we see the way the world is not as something fixed and inevitable that we can take or leave, but as something potentially changeable, and in which we are always constructively implicated.Footnote12 By contrast, complicit relations are characterised by a stubborn refusal to recognise our freedom, even as we exercise it.

To identify the ethical character of an agent’s relation to clothing and practices of dress, we propose asking two key questions motivated by the initial feminist critiques of women’s clothing. First, how does the agent care for their clothes? And second, how does the agent grasp their clothes as meaningful? By focussing on some illustrative examples, we examine how we can avoid the dead-end created by choice as liberation and opting out, and say something positive about feminist dress.

3.1. How does the agent care for their clothes?

As we have seen in Section 2.1, instead of asking how much women care about their clothes, a more productive analysis of complicity asks: what kind of care do women give their wardrobes? Are they treating them as substitutes for having a life, or as enabling them to live their life? Do they exhibit a dominating care for themselves as an aesthetic object that alienates them in their clothing such that ‘spots, tears, botched dressmaking’ become ‘a real disaster … a catastrophe’, a threat to one’s personhood (TSS: 579); or a more liberating care that enables them to explore new sides of themselves and possibilities for living and doing things in the world? In other words, is the way they care about their clothes one that just reproduces patriarchal models or one that actively negotiates and remakes them?

What we could call the ideal of liberating care is compatible with a very diverse range of practices and is something many women already exemplify in their own lives. Consider bell hooks’ description of her grandmother, Sarah Oldham, a woman steeped in the folk culture of the working-class black South: ‘as a quiltmaker she was constantly creating new worlds, discovering new patterns, different shapes. To her it was the uniqueness of the individual body, look, and soul that mattered’ (hooks Citation1995, 158). This attitude towards the decoration of the self and the home contrasted starkly with that of hooks’ own mother, who aspired to conformity through imitation of ‘acceptable appearances and styles’ seen in advertisements (Citation1995, 158). For hooks, what made her grandmother Sarah an ‘example of personal freedom and creative courage’ was her cultivation of beauty that actively resisted ‘a culture of domination that recognizes the production of a pervasive feeling of lack … as a useful colonizing strategy’ (Citation1995, 164). And yet, Sarah Oldham was not engaged in a primarily intellectual exercise. Similarly, liberating care is not a matter of thinking about what one wears and how it challenges the patriarchy. Rather, it is exemplified in how we relate to the world, and in our often unconscious ways of being-in and relating to our clothes.Footnote13 It can be embodied in taking pleasure in making, styling and purchasing clothes; in the way some women select a ‘uniform’ that works for them, or in how others have a multifaceted wardrobe that enables them to creatively try out a range of styles. Liberating care does not necessarily demand a huge amount of conscious thought, and manifests in the engagement with clothes that is always already part of our lives and cultural traditions. It does not necessarily require any extra effort on a day-to-day basis.Footnote14 Rather, it is about taking what we’re already doing every day and potentially doing it differently. Moreover, liberating care is certainly compatible with a wide range of aesthetic sensibilities. In this way, our relational approach avoids the pitfalls that made opting out so unappealing: its prescriptivism, its (possibly) implicit misogyny, its neglect of the self-expressive dimension of clothing and of the joys and pleasures it can bring.

To further illuminate this ideal of liberating care, it is useful to look at some more examples. First consider Meg McElwee, the designer behind ‘Sew Liberated’, a popular sewing patterns company. McElwee claims that many women’s clothing practices are in need of change, but her positive vision does not shun care or choice (Sew Liberated Citation2022). McElwee’s Sew Liberated is built around thrifting, making, mending, and ‘crafting’ your own personal style – all activities that require the time, attention, and creative energy opt out theorists find wasted on clothes. Unlike the Rational Dress Society’s jumpsuit, Sew Liberated is not a move toward a strictly utilitarian wardrobe, even if McElwee advocates a relatively sparse one. In her model of dress, clothes should be well considered so that every piece is ‘something you will wear all the time’ (Sew Liberated Citation2022): long-lasting, appropriate for your lifestyle, fitting your body instead of struggling against it or trying to make it over, and reflecting your own design modifications.

Unlike the ungendered jumpsuit, Sew Liberated clothes do not attempt to do away with feminine dress, nor do they simply embrace it. McElwee’s pattens, with their flowy skirts, floor-length dusters, and straight-fitting overalls are neither rejections, nor full acceptances of conventional feminine silhouettes (). The idea of having clothes that complement rather than expose the body; of making garments that are ‘comfortable and useful, but in no way plain’; and of boosting one’s ‘sense of freedom with what we put on our bodies’, are all ways of embodying liberating care. They reflect a commitment to dressing for agency, rather than for being a beautiful passive object (Sew Liberated Citation2022).

Figure 6. ‘Sew Liberated’ pattern designs by Meg McElwee (https://sewliberated.com).

It may be easy to see how a designer like McElwee can express liberating care when clothes and fashion are such a central aspect of her life, her work and her identity. But the more interesting ethical question is: how can this liberating care play out in everyday cases where clothes and fashion are just one aspect of our lives? Liberating care need not involve the effort that making your own clothes demands. Nor does it require a wardrobe as sparse as McElwee’s. For a more everyday characterisation, consider Iris Marion Young’s statement that:

There is a certain freedom involved in our relation to clothes, an active subjectivity … the freedom to play with shape and color on the body, to don various styles and looks, and through them exhibit and imagine unreal possibilities … Such female imagination has liberating possibilities because it subverts and unsettles the order of respectable, functional rationality in a world where that rationality supports domination. The unreal that wells up through imagination always creates the space for a negation of what is, and thus the possibility of alternatives. (Young Citation2005, 73–74)

Intensive care can be liberating when it involves joyful moments of styling and selecting our looks. However, as Beauvoir warns (TSS: 579), when clothing becomes the way to express oneself, it can lead into much more dominating and subordinating logics of care. When the stakes are so high, our lives become the clothes and we become paralysed in the world as agents, walled in by alienating care for the self as an aesthetic object.Footnote15 To count as liberating care, our attention to our clothes must continue to focus on how they enable us to be in the world, rather than merely appear in it, a concern we see articulated in Hélène Cixous’ example of her Sonia Rykiel dress.

In her Rykiel dress, Hélène Cixous feels that ‘there is no rupture … everything is continuous’ (Citation1994, 96). The relation Cixous has to the dress enables a kind of smooth, non-antagonistic relation between her and the world. The dress she wears extends the possibilities of her self and her body in ‘nonviolen[t]’ ways, the ‘clothes never turn back against the body, never attack it, never seek to put it in one’s place’ (Citation1994, 97). This virtue is not contained within the dress itself, but in the particular relation between Cixous and the garment: in it, Cixous assumes herself and the world as changeable. Contrast this with Jennifer Baumgardner’s relation to her clogs:

high heels can be seen as, like the corset, a symbol of women’s oppression, but I actually feel equally oppressed by my clogs … For me, sliding into generic and unconscious comfort is dying a little (Baumgardner Citation2011, x–xi)

3.2. How does the agent grasp their clothes as meaningful?

A relational ethics of dress cannot be prescriptive about what we should or should not wear, because liberating care manifests itself in very different ways, but also because the meaning of our clothes is unstable (recall the hotpants example). However, just as there are better and worse ways to care for our clothes, there are better and worse ways to relate to the meaning of specific garments. In evaluating complicity, we must ask: was the wearer trying to passively replicate a patriarchal ideal of feminine beauty or ‘the look’ of the season, or was she more actively navigating the available options in ways fitting for her specific, embodied situation, for her goals and aims? On our view, it does not follow that simply not following dominant norms and wearing something ‘counter-cultural’ constitutes non-complicit dressing, because it is the relation one has to one’s clothes that is crucial. The ‘1970s women’s liber’ who opts out of conventional norms of dress, but stringently follows the rules of her social milieu, unquestioningly adopting lumber jack shirts, loose trousers, and Doc Marten boots, could be as complicit in her relation to her clothes as the woman who perfectly conforms to the demands of stereotypical feminine beauty. Regardless of what they wear, both embody a passive reproduction of some norms, rather than an active negotiation of the available options.

What does this active negotiation look like? To navigate our clothes in a non-complicit way, we must not regard their meaning as too fixed nor as too flexible; we must not over endow clothing with social significance,Footnote16 but equally we must not refuse to recognise how certain practices or items are commonly received. The meaning of clothing is constituted by a dynamic relation between the clothing, the wearer, their embodied being, their comportment, and their social context. Some of this meaning will be relatively hard to detach from garments. After all, the reason the hotpants show up as subversive when worn by the plus-sized woman is because of their strong association with conventional notions of feminine beauty and sexuality. But while we cannot totally transcend the expectations that surround certain items of clothing simply by choosing or not choosing them, we may be able to negotiate, redeploy and reinterpret the meaning of some clothes. Although, as we shall see, such negotiation is not possible with all garments.

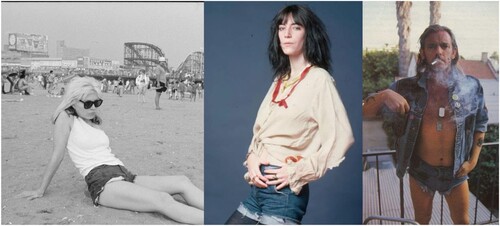

As we have argued, it is possible to not convey what Daisy Duke does when wearing hotpants by changing the body of the wearer, the context and the styling of the garment. But this reworking, although fundamentally a matter of reorganising these relations, also depends on some features of hotpants themselves. A pair of ‘short shorts’ can leave the lower body free to move, be cool on hot summer days, and evoke a rich history of associations to punk rock and metal – think Debbie Harry, Patti Smith, and Lemmy from Motörhead (; Newell-Hanson Citation2016). The meaning of the hotpants that arises from all these relations is relatively ambiguous, open to negotiation and even subversion. Contrast this with the stiletto heel, which is so strongly associated with a gendered script of femininity that it is hard to pry the two apart (Chambers Citation2008, 2, 28–29). The stiletto heel requires a constrained gait and is designed to achieve a tensioning of the body – positioning the wearer as primarily an immobile and delicate object. Rather than enabling the agency, continuity and smoothness Cixous describes, the stiletto heel cuts us off from possibilities and constrains us, especially those of the ‘dangerously high kind you have to take a deep breath before buckling into’ (Newbold Citation2022). Even pairing the stiletto with combat trousers and a big jumper does not fully subvert these effects, making it a very difficult candidate for negotiation.

Figure 7. Debbie Harry (photo by Roberta Bayley/Redferns), Patti Smith (photo by Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images) and Lemmy Kilmister (source unknown) wearing hotpants (Ilyashov Citation2018; Kennelty Citation2020).

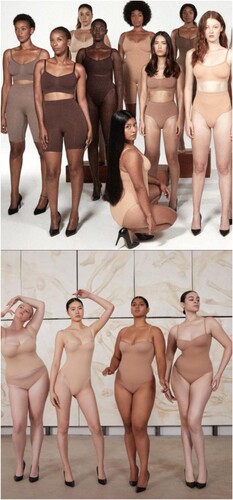

For another example of this critical edge of our relational ethics, consider Lizzo’s new range of size-inclusive shapewear (). According to Lizzo, her ‘body positive’ line with its expanded size range is positively empowering. It allows women to take ‘ownership of your physical presence, your identity’.

It’s about you … not allowing a piece of clothing to dictate how you should feel about your body. You’re telling the piece of clothing, ‘This is how I feel about my body today.’ … We’re giving the consumer the autonomy to choose different levels of compression and style. They're really the ones who are making the decisions. They’re the boss. You know, it’s in their hands. (Tashjian Citation2022)

Figure 8. Lizzo’s Shapewear Line Yitty (https://yitty.fabletics.com/).

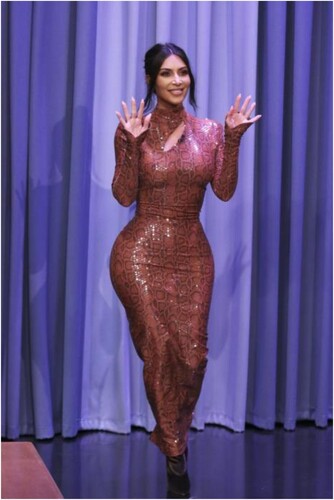

Kim Kardashian’s influential sartorial habits, which have been instrumental in catapulting the extreme shaped look into the mainstream (Kardashian has a highly successful line of shapewear herself, see ), are a perfect example of this difficulty. The highly shaped gowns that make Kardashian an icon are also the ones that make it impossible for her to perform basic human functions, like sitting down, going to the bathroom, climbing up a set of stairs, entering a car or even walking in a straight line (Van Soest Citation2022, ). Even if these garments are styled on non-normative bodies, these are clothes that encourage a self-relation that turns the wearer into a mere aesthetic object and so are extremely hard to wear in non-complicitous ways.Footnote18

Figure 9. Kim Kardashian’s Skims shapewear line (Skims Citation2020, Citation2022).

Figure 10. ‘Hello: Kim Kardashian makes her entrance onto The Tonight Show’ (Powell Citation2019).

Although compatible with many ways to dress, our relational ethics contrasts with the choice as liberation paradigm in that it is not compatible with whatever women choose. If objectifying modes of dress put us in a state of discomfort and heightened awareness – constantly pulling down our skirts and pulling up our tops – they undermine the smoothness and continuity that enables agency, and so we have reasons to reject them. The fact that women choose these garments matters, but it is not decisive. What is more important is that there is an active negotiation present in one’s relation with one’s clothes. But this idea of negotiation should not be mistaken for a kind of ‘sexy is powerful’ feminism (Hakim Citation2011; Eggerue Citation2020, 57–58, 157–159; see also Tolentino Citation2019, 63–94) that encourages us to embrace patriarchal rules and restrictions as a way to get ahead in the world, to put on our high heels so we can rise to the boardroom. Here there is no genuine negotiation with patriarchal norms of professional dress, rather there is a stubborn embrace of the way the world is as inevitable and unchangeable, a denial of our situated agency: all we can do is play the patriarchal ‘loosing game’.

One may object that this makes non-complicity too demanding. For example, in 2016 Nicola Thorp, a temporary receptionist at Price Waterhouse Cooper, was sent home without pay for refusing to wear 2–4 inch heels (Khomami Citation2016). One may be concerned that the costs of non-compliance are too high to bear, especially for women in precarious positions or low paid jobs who have little bargaining power, and who may risk losing their income and their livelihood. However, as we have argued, our ideal of non-complicity is not simply one of all-out resistance or rejection, but of negotiation within more or less constrained situations. Although Thorp’s refusal to comply with a sexist dress code is a laudable example of non-complicity, it is not the paradigm case. One can often limit the risks incurred by interpreting and navigating social scripts around dress strategically, nodding to conformity while not compromising one’s own values. There are heels and there are heels – one can frequently get away with a ‘mini-heel’ instead of ‘proper black stilettos’ (Kale Citation2019). Indeed, this kind of negotiation is often already familiar to women from lower income backgrounds who have to be more selective and creative in their clothing choices, finding items that will work in a range of situations and contexts. From the woman who refuses to keep things ‘for best’, or who purchases clothes with an eye to how they can be dressed up for work and dressed down for weekend wear, to the woman who dyes her wedding dress so it can be used for other events; working class women are frequently more adept than middle- or upper-class women at the creative subversion and negotiation that characterises non-complicit dressing. Without much disposable income, one cannot immediately go out and buy a fresh outfit when a new trend, work or social occasion demands it, and must often be ready to creatively bend social conventions out of necessity. Non-complicit dressing is not a ‘middle-class activity’ or one that necessarily demands a huge amount of time and money. It is a way of navigating the middle ground by neither fully leaning into the status quo, nor fully opting out.

Accordingly, no garments are in principle off-limits: the high heels worn to a meeting to strategically increase one’s stature, or the low-cut top worn on a night out to express and enhance the feeling of oneself as a sexual being are not immediately or necessarily expressions of a complicit relation with clothes. We always need to ask critical questions about what possibilities for genuine agency the garments open up rather than shut down. And, because complicity is an ongoing relation, escaping complicity is not an all-or-nothing matter: it is a process and an achievement over time. There are so many variables in the web of relations that endow our garments with meaning that it is impossible, in the abstract, to make definitive judgments about them. As Beauvoir put it,

What must be done, practically? Which action is good? Which is bad? To ask such a question is also to fall into a naive abstraction. … Ethics does not furnish recipes any more than do science and art. One can merely propose methods. ( (Citation1947) 2018, 144–145).

4. Conclusion: revisiting bimbocore

One might worry that this ethical relation to our clothes saddles women with even more burdensome demands on their time and energy. On top of all the other things that make getting dressed in the morning hard, must women also worry about whether they are ‘dressing like a feminist’? Having a non-complicit relation to our wardrobes can, in one sense, require minimal effort. It can involve simply figuring out your own Steve Jobs-like uniform. It certainly does not require the time and money that sewers like McElwee put into their garments, or the joy and excitement that Young expresses. But it does require the kind of care that they seem to have: a critical engagement with clothes as not simply chosen, and not simply given; as opening up possibilities for living in the world, but not as escapes from it; as parts of who we are, without being all or even essentially what we are. This kind of care, in turn, determines the way we understand the meaning of our clothes: as neither absolutely fixed by the social world, nor totally dictated by our intentions; as always a product of complex relations between contexts, bodies, agents, cultures, and cloth; and as something we, as responsible wearers must creatively negotiate. Although we have focussed our analysis on the historically vexed question of women’s relation to clothes, it is worth noting that men are always already implicated in the ethical questions raised by clothing. Their reactions and expectations are part of how women are made to care about their clothes in dominating ways. But men are also social agents who must negotiate their own relation to social norms. As we have seen with Steve Jobs, men can no more opt out than can women. And, as Lemmy’s ‘short shorts’ show, the meaning of the clothes that men wear must also be apprehended by them as something flexible and changeable.Footnote19 Men too must be responsible wearers that take up an active and creative relation to social norms of dress, including patriarchal ones.

We started out by describing bimbocore as illustrative of the impasse created by opting out and choice as liberation. On our approach, we can agree that the new bimbos are not simply being brainwashed, but we can also resist their simplistic calls to just ‘wear whatever the fuck you want’ (Richards Citation2022). Instead of focusing on what bimbos wear, we should focus on their relation with their clothes. First, we might worry about their dreams of ‘having more than 100 pairs of shoes’ (Princess Citation2020), their calls to ‘only focus on you and your looks all the time’ (Fifi Citation2021), their constant characterisation of dressing well as ‘looking hot’, and the way their practices of dress are inextricably linked to living for an online audience. Bimbocore adherents seem to care about dressing up as if they were primarily aesthetic, highly sexualised objects, not agents in the world. Second, bimbocore fetichizes choice and misunderstands how meaning works. Just as you cannot wear hotpants and be ready for the boardroom, you cannot pair push-up bras with exposed thongs and latex bodycon dresses and say this has nothing to do with being a sex object, as the new bimbos often insist (Chrissy Citation2020; Citation2022). The ‘low-rise miniskirts and pink pumps’ may have never been ‘the enemy to begin with’ (Reilly Citation2022), but neither are they neutral elements whose meaning is unilaterally stipulated by the wearer – especially when they are adopted as part of a complete ‘look’, rather than styled in idiosyncratic or original ways. Finally, the newfound inclusivity of bimbocore does not by itself subvert patriarchal norms. Like Lizzo’s shapewear line, bimbocore finds new ways of conforming to old norms, albeit in a different context, on a different body, or with a louder cry that this is an ‘active choice’. Importantly, we can say all this without outlawing pink or low-rise miniskirts and without denying what the new bimbos get right: that clothes can be a freeing, creative, and joyful part of our lives.

Acknowledgements

Earlier drafts of this paper were presented at various events in 2022: The OZSW Moral Psychology Group at the University of Tilburg, a workshop on ‘Injustice, Resistance and Complicity’ at the University of Groningen, the British Phenomenological Society’s annual conference in Exeter, and the University of Warwick’s Post-Kantian Society. Thank you to the organisers of these events for facilitating discussions of our work, to the audiences for their comments, and to the two reviewers at Inquiry for their helpful feedback and enthusiasm about the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Bimbocore is just one of several recent ‘hyperfeminine’ fashion trends, including barbiecore, balletcore, and the coquette look (Nylon Citation2022).

2 The most cited example of the ‘girlboss’ is Sheryl Sandberg, author of the 2013 best-seller Lean In. Examples of the ‘cool girl’ include sitcom characters Rosa Diaz (Brooklyn Nine-Nine) and Robin Scherbatsky (How I Met Your Mother) (The Take Citation2022).

3 We use the term ‘objectification’ to mean broadly the problematic reduction of women to their dimension as sexual objects. On sexual objectification see Nussbaum (Citation1995), Langton (Citation2009) and Jütten (Citation2016).

4 Heather Widdows argues that ‘gendered inequality is no longer the primary concern when it comes to critiquing the beauty ideal in its current form’, as men are also required to do a lot of beauty work (Citation2018, 249–250). Widdows’ interest is primarily in practices that shape the body such as cosmetic surgery, dieting and sculpting exercise regimes (Citation2018). By her own admission, her concern is not primarily with clothes – her focus is on ‘the cut of the breast, rather than the cut of the dress’ (Citation2019a). We follow Chambers (Citation2008, 29) in contending that, in the realm of dress, there are still unequal and subordinating gendered norms.

5 For different forms of this argument see Dworkin (Citation1974, 155), Jeffreys (Citation2005, 2, 26), Garcia (Citation2021, 176).

6 A similar strategy is recommended by Robin Zheng to combat structural injustice by pushing the boundaries of our social roles (Citation2018).

7 For earlier choice as liberation arguments see Radcliffe Richards Citation1980, 240–242; Wolf (Citation1990) 2002,272–273; Lehrman Citation1997, 7–36, 65–96; Scott Citation2005.

8 Widdows characterises debates about beauty as having reached a similar impasse where ‘some feminists continue to advocate resistance and others argue that all beauty engagement is empowering as long as it is chosen’ (Citation2021, 263). But unlike us, Widdows argues that to move forward we must turn away from thinking about how individuals navigate the world and focus primarilyon changing social norms through collective action. For related characterizations of this tension with respect to beauty and feminist resistance see Radcliffe Richards Citation1980, 222; Davis Citation1995, 57; hooks Citation1995, 163–164; Cahill Citation2003, 43.

9 As the Boston Review reported, after Dworkin’s death: ‘Few eulogists could resist a jibe at Dworkin’s appearance, which had become synonymous with what critics saw as her unappetizing and feral rhetoric … One analysis found that Dworkin’s physical appearance was mentioned in 61 percent of obituaries and postmortems’ (Lybarger Citation2019). Steinem was ‘criticised in the ’70s by those who felt her glamorous persona was at odds with her feminist ideology, Steinem never shied away from fashion’ (McDermott Citation2020). For discussion of this media dynamic see Wolf (Citation1990) 2002, 274–275.

10 Meyers (Citation2002) makes a similar point about agency in cases of internalized oppression. See also Beauvoir’s characterization of certain fashionable women in The Ethics of Ambiguity: ‘A frivolous lady of fashion can have this mentality of the serious as well as an engineer. There is the serious from the moment that freedom denies itself to the advantage of ends which one claims are absolute.’ (Citation1947) 2018, 49–50)

11 This understanding of freedom is common to the phenomenological tradition (BT; TSS). It is also present in feminist discussions of internalized oppression (Meyers Citation2002; Bartky Citation1990) and in approaches to injustice such as Iris Marion Young’s, which recognize that ‘a comprehensive explanation of injustice should include reference to both agency and structure’ (Aragon and Jaggar Citation2018, 442–443).

12 On this view, cases in which the agent has no other option but to comply are better described as cases of coercion. Complicity occurs when an agent actively and to some extent ‘freely’ takes up subordinating practices of dress, as is the case in bimbocore. For more on this point see Knowles Citation2022, 1324–1326.

13 Phenomenologically analysing the relation an agent has to their clothes does not necessarily depend on asking the agent directly, but analysing their relations to themselves and the world by focussing on how they comport themselves (Bartky Citation1990, 88–90, 95–96).

14 cf. Zheng on pushing the boundaries of your social roles (Citation2018, 878, 879, 881 note 10).

15 This is not to say that there is not an important and respectable agency in the self-decorative care acts that women commonly engage in, or that clothes cannot be a very central part of our lives, as in the case of McElwee. Rather, we aim to highlight the distinction between dedicating time and aesthetic attention to oneself in a way that can be liberating from modes in which such attention becomes dominating. For more on the importance of recognizing clothes as a site of agency and (artistic) self-expression see Knowles (Citation2021b).

16 This applies both to our own clothes and the clothes of others. During the murder trial of Latisha King, an American trans girl murdered by her classmate in 2008, the defence overendowed King’s clothes with meaning as if they could explain her murder. Latisha’s dress ‘names Latisha as a culpable subject, announcing her perversion’ (Salamon Citation2018, 137). This attitude to clothing is widespread in the treatment of victims of sexual violence who are asked ‘what were you wearing?’

17 Widdows makes a similar point: ‘fat acceptance campaigns often conform to all but the thin feature of the [beauty] ideal. Apart from being plus size, the bodies are firm, smooth, and young’ (Citation2019b).

18 A similar analysis could be made for ‘modest’ clothing. Again, the problem is not the clothes themselves, but how they enable or restrict agency, and open up or shut down possibilities. In this way, we can highlight the liberating possibilities of the burqa as a form of ‘portable seclusion’ in gender segregated societies (Abu-Lughod Citation2002:36), recognise the various forms of negotiation within prescribed norms (Narayan Citation2002), and the importance of religion and tradition to self-understanding (Khader Citation2016), while acknowledging that many pieces of modest clothing can inhibit movement, encourage an objectifying self-relation, and restrict possibilities for self-expression and action.

19 For a reflection on the meaning and care involved in traditionally masculine clothing see Bari Citation2020, 81–135.

References

- Abu-Lughod, L. 2002. “Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others.” American Anthropologist 104 (3): 783–790.

- Aragon, C., and Alison. Jaggar. 2018. “Agency, Complicity and the Responsibility to Resist Structural Injustice.” Journal of Social Philosophy 49 (3): 439–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12251.

- Bari, S. 2020. Dressed: A Philosophy of Clothes. New York: Basic Books.

- Bartky, S. 1990. Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression. New York: Routledge.

- Baumgardner, J. 2011. “Foreword.” In Fashion – Philosophy for Everyone: Thinking in Style, edited by J. Wolfendale, and J. Kennett, ix–xii. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Beauvoir, S. de. (1949) 2011. The Second Sex (TSS in text). Translated by C. Borde and S. Malovany-Chevallier. New York: Vintage Books.

- Beauvoir, S. de. (1947) 2018. The Ethics of Ambiguity. Translated by B. Frechtman. New York: Open Road.

- Benhabib, S. 1987. “The Generalized and the Concrete Other: The Kholberg-Gilligan Controversy and Feminist Theory.” In Feminism as Critique: Essays on the Politics of Gender in Late-Capitalist Societies, edited by S. Benhabib, and D. Cornell, 77–96. Oxford: Polity.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Cahill, A. 2003. “Feminist Pleasure and Feminine Beautification.” Hypatia 18 (4): 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2003.tb01412.x.

- Chambers, C. 2008. Sex, Culture and Justice: The Limits of Choice. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Chrissy [@chrissychlapecka]. 2020, November 2021. “Who is the Gen-z bimbo? [Video].” TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@chrissychlapecka/video/6899540522721922310.

- Chrissy [@chrissychlapecka]. 2022, August 4. “Good Nigh [Video].” TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@chrissychlapecka/video/7127891849515273518.

- Cixous, H. 1994. “Sonia Rykiel in Translation.” In On Fashion, edited by S. Benstock, and S. Ferris, 95–99. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Dalessandro, A. 2015, June 17. “9 Ways to Wear Plus-size Shorts this Summer.” Bustle. https://www.bustle.com/articles/91002-9-ways-to-wear-plus-size-shorts-this-summer-because-your-legs-deserve-to-see-the-sun.

- Davis, K. 1995. Reshaping the Female Body: The Dilemma of Cosmetic Surgery. New York: Routledge.

- Dworkin, A. 1974. Woman Hating. New York, NY: Plume.

- Eggerue, C. 2020. How to get Over a boy. London: Hardie Grant.

- Fifi [@gsgetlonelytoo]. 2021, December 24. “Reply to @krisandsatan #greenscreen [Video].” TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@gsgetlonelytoo/video/7045340346376637701.

- Freeman, L. 2011. “Reconsidering Relational Autonomy: A Feminist Approach to Selfhood and the Other in the Thinking of Martin Heidegger.” Inquiry 54 (4): 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2011.592342.

- Frye, M. 1983. The Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

- Gadamer, H. (1975) 2004. Truth and Method. 2nd revised ed. Translated by J. Weinsheimer and D. G. Marshall. London: Continuum.

- Garcia, M. 2021. We are not Born Submissive: How Patriarchy Shapes Women’s Lives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- GMB [@griffinmaxwellbrooks]. 2020, December 3. “That’s Water in My Glass [Video].” Tiktok. https://www.tiktok.com/@griffinmaxwellbrooks/video/6902159284725894406.

- Grewal, G. 2022. Fashion | Sense: On Fashion and Philosophy. London: Bloomsbury.

- Grimes, C. 2022, March 25. “Why TikTok's Bimbocore Trend is an Act of Modern Feminism.” Hypebae. https://hypebae.com/2022/3/tiktok-bimbocore-trend-feminism-op-ed-elle-woods-kim-kardashian-paris-hilton.

- Haigney, S. 2022, June 15. “Meet the Self-Described ‘Bimbos’ of TikTok.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/15/opinion/bimbo-tiktok-feminism.html.

- Hakim, C. 2011. Honey Money: The Power of Erotic Capital. London: Penguin.

- Heidegger, M. (1927) 1962. Being and Time (BT in text). Translated by J. Macquarie and E. Robinson. Southampton: Basil Blackwell.

- Hillman, B. L. 2013. “‘The Clothes I Wear Help Me to Know My Own Power’: The Politics of Gender Presentation in the Era of Women’s Liberation.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 34 (2): 155–185. https://doi.org/10.1353/fro.2013.a520040.

- hooks, b. 1995. “Beauty Laid Bare: Aesthetics in the Ordinary.” In To be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism, edited by R. Walker, 157–167. New York: Anchor Books.

- Ilyashov, A. 2018, June 22. “See the Evolution of Summer's Sexiest Shorts from the 1940s to the 2000s.” Yahoo! News. https://uk.news.yahoo.com/daisy-duke-beyonce-summers-sexiest-shorts-came-111130143.html.

- Jeffreys, S. 2005. Beauty and Misogyny: Harmful Cultural Practices in the West. London: Routledge.

- Jennifer [@thepetiteproblem]. 2022, October 9. “#bimbo #hellokitty #pink #itgirl #thepetiteproblem #softgirl #spoiled [Video].” TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@thepetiteproblem/video/7152301449165262126.

- Jütten, T. 2016. “Sexual Objectification.” Ethics 127 (1): 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/687331.

- Kale, S. 2019, July 11. “‘Why Should I Have to Work on Stilts?’: The Women Fighting Sexist Dress Codes.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/jul/11/why-should-i-have-to-work-on-stilts-the-women-fighting-sexist-dress-codes.

- Kennelty, G. 2020, November 4. “Lemmy's Advice to Motörhead guitarist Phil Campbell: Don't Wear Shorts on Stage.” Metal injection. https://metalinjection.net/shocking-revelations/lemmys-advice-to-motorhead-guitarist-phil-campbell-dont-wear-shorts-on-stage.

- Khader, S. J. 2012. “Must Theorising About Adaptive Preferences Deny Women's Agency?” Journal of Applied Philosophy 29 (4): 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5930.2012.00575.x.

- Khader, S. J. 2016. “Do Muslim Women Need Freedom? Traditionalist Feminisms and Transnational Politics.” Politics & Gender 12 (04): 727–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X16000441.

- Khomami, N. 2016. “Receptionist ‘Sent Home from PwC for not Wearing High Heels’.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/may/11/receptionist-sent-home-pwc-not-wearing-high-heels-pwc-nicola-thorp.

- Knowles, C. 2013. “Heidegger and the Source of Meaning.” South African Journal of Philosophy 32 (4): 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/02580136.2013.865101.

- Knowles, C. 2021a. “Articulating Understanding: A Phenomenological Approach to Testimony on Gendered Violence.” International Journal of Philosophical Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2021.1997389.

- Knowles, C. 2021b. “On Doing Philosophy and Looking Good.” The Philosophers’ Magazine. https://www.philosophersmag.com/essays/231-living-the-life-of-the-mind.

- Knowles, C. 2022. “Beyond Adaptive Preferences: Rethinking Women’s Complicity in Their own Subordination.” European Journal of Philosophy, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejop.12742.

- Langton, R. 2009. Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Le, M. 2022, September 21. “Explaining the hyperfemininity aesthetic [Video].” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6yZi-Wrv8s&t=871s.

- Lehrman, K. 1997. The Lipstick Proviso: Women, Sex & Power in the Real World. New York: Doubleday.

- Levy, A. 2005. Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture. London: Pocket Books.

- Linton, D. 2022, May 8. “Is Being Called a Bimbo now a Compliment?.” Vogue. https://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/bimbo.

- Lybarger, J. 2019, February 23. “Finally Seeing Andrea.” Boston Review. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/jeremy-lybarger-andrea-dworkin/.

- Mac Donnell, C. 2022, November 19. “Blazers Out, Birkenstocks in: How Smart Casual Work ‘Uniforms’ Can Free up Brain Power.” The Observer. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2022/nov/19/blazers-out-birkenstocks-in-how-smart-casual-work-uniforms-can-free-up-brain-power.

- McDermott, K. 2020, September 10. “It’s Ok to be Obsessed with Gloria Steinem’s Style.” Vogue. https://www.vogue.co.uk/fashion/article/gloria-steinem-style.

- Melo Lopes, F. 2019. “Perpetuating the Patriarchy: Misogyny and (Post-)Feminist Backlash.” Philosophical Studies 176 (9): 2517–2538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1138-z.

- Melo Lopes, F. Forthcoming. “Criticizing Women: Simone de Beauvoir on Complicity and Bad Faith.” In Analytic Existentialism, edited by B. Marušić, and M. Schroeder. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Meyers, D. 2002. Gender in the Mirror: Cultural Imagery and Women’s Agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mohamed, Y. 2022, October 14. “Steve Jobs - Why Did He Wear the Same Outfit Every Day?.” Medium. https://medium.com/macoclock/steve-jobs-c0cb216ba31.

- Morgan, L. 2022, March 15. “Bimbofication is the Empowering New Trend that's Reclaiming the Power of Hyper-femininity.” Glamour. https://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/bimbofication.

- Narayan, U. 2002. “Minds of Their own: Choices, Autonomy, Cultural Practices and Other Women.” In A Mind of One’s Own: Feminist Essays on Reason and Objectivity, edited by L. Antony, and C. Witt. 2nd ed., 418–432. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Newell-Hanson, A. 2016, June 13. “A Brief History of Denim Cutoffs, from Daisy Duke to Debbie Harry: Considering the Dangerous, DIY Appeal of Jean shorts.” I-D. https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/59bv5b/a-brief-history-of-denim-cutoffs-from-daisy-duke-to-debbie-harry.

- Newbold, A. 2022. “The Return of the High Heel.” Vogue. https://www.vogue.co.uk/fashion/article/high-heel-trend.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 1995. “Objectification.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 24 (4): 249–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x.

- Nylon. 2022. “Core Club.” https://www.nylon.com/core-club.

- Powell, Emma. 2019, February 8. “Kim Kardashian Flaunts Figure in Skin Tight Snakeskin Dress for Jimmy Fallon Appearance.” Evening Standard. https://www.standard.co.uk/showbiz/celebrity-news/kim-kardashian-flaunts-figure-in-skin-tight-snakeskin-dress-for-jimmy-fallon-appearance-a4061071.html.