Abstract

This contribution presents descriptive findings on individual attitudes and public opinion based on the International Social Survey Program Role of Government module. It covers the period from 1985 to 2016 and is guided by the idea that attitudes and opinions are aligned with the international divisions in different welfare regimes. The analysis includes all countries that fielded this ISSP survey continuously from 1985 (Australia, Germany, United Kingdom, and the United States) or 1990 (Hungary, Israel, and Norway). Our results show that attitudes and opinions remain rather stable over time and parallel the different welfare regimes. There is no clear evidence of a growing support for liberalization and deregulation across all countries despite the increasing market orientation in many countries.

Introduction

This contribution builds on the overview and history of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) Role of Government (ROG) module presented by Jonas Edlund and Arvid Lindh in the previous issue of the International Journal of Sociology (Edlund and Lindh 2019). It presents descriptive findings on attitudes and opinions regarding the role of government covering the period from 1985 to 2016 and all countries that have fielded the ROG modules since 1985 or 1990, respectively.

We follow the idea that public opinion toward the government derives from historically grown values and ideologies (Abercrombie Citation1990; Haller, Bogdan, and Zwicky Citation1995) and that it varies across countries and welfare regimes. We consider institutions and public opinion interdependent: Citizens and voters have legitimated different welfare state systems in the course of the past decades. Their views of social justice, of what the state is responsible for and how to reach predefined social objectives, have a decisive impact on the role of government. Conversely, state systems have shaped how people think about and act within the routines of welfare systems (Arts and Gelissen Citation2001), for instance, about state intervention in the economy or social assistance for individuals in need.

Against this background, we assume that the analyzed attitudes and opinions toward the role of government are structured similarly to welfare regimes and thus follow analyses such as Stefan Svallfors (Citation1997, Citation2003) and Ursula Dallinger (Citation2010). Consulting literature on types of regimes, we follow Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s (Citation1990) classical three worlds of welfare capitalism (liberal, conservative, and social democratic regimes) and the subsequent subdivisions such as radical welfare states, which are seen as a type of liberal regime (Castles and Mitchell Citation1993), and former socialist countries (Fenger Citation2007; Kollmorgen Citation2009). As for the latter, our analysis, however, includes only Hungary. Hungary is considered a state-led conservative welfare state (Kollmorgen Citation2009) and distinguished from West European, former USSR (such as Russia or Ukraine), and developing (such as Romania or Moldova) welfare states.

Historically grown values and ideologies are deeply rooted in the mindset and culture of a society. Clem Brooks and Jeff Manza (2006) found evidence that welfare policies are remarkably stable because of underlying public support and opinion. Public opinion toward the role of the state should therefore be rather constant. Yet, the large social and socioeconomic structural changes since the 1990s might also be reflected in people’s views (Eder Citation2017).

Big changes took place in the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s, when state socialism in East Europe was replaced by liberal market economies and when West European politicians considered the path of “third way politics” (Powell and Barrientos Citation2004). These politics were characterized by merit-based entitlements to state assistance and less state intervention in economic affairs (deregulation and liberalization) in combination with growing individualism and self-responsibility. Given that a majority of citizens voted for this political line, we expect that people have become more critical toward state intervention since the 1980s. Scholars also see social-psychological learning processes of “normative accommodation” (Sachweh Citation2010) in this context. Individuals adapt their views and expectations regarding state intervention to their living circumstances, which can lead to changing norms of social justice.

In sum, using time-comparative data for a set of countries allows testing whether country differences have been rather persistent since the mid-1980s or whether there is any evidence of growing preferences for liberalization and deregulation. The following section provides a brief overview of the data and methods used in this research note. This methods part is followed by the results section on cross-national and time-comparative differences. The discussion and conclusion sections connect our findings with the classification of different regimes. We conclude that cross-country differences can be traced back to historically grown welfare regimes and that there is no clear evidence of a growing liberalization and deregulation across all countries despite the ongoing deregulation in many countries.

Data and methods

Our analysis is based on public opinion data from the ISSP. The ROG modules were fielded in 1985, 1990, 1996, 2006, and 2016. These surveys are random samples of the adult population in each country, which were collected face-to-face or via mail. The sample sizes vary but are usually between 1,000 and 1,500 respondents. The data were collected in 6 countries in 1985, 10 countries in 1990, 24 countries in 1996, and 35 countries in 2006 and 2016, respectively. Detailed information on the ISSP can be found on www.issp.org. Data can be downloaded free of charge at GESIS https://www.gesis.org/issp/home/.

Our report focuses on those countries that started to collect the data in the first (1985) or second (1990) round and have continued to take part in all subsequent waves. It includes Australia, Germany-West, Hungary, Israel, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States. For comparative reasons, Germany is limited to the former Western Germany, as data for 1985 and 1990 were not collected in Eastern Germany. Israeli data are limited to the Jewish population, as the Arab population was not included in the early waves.

The time-comparative part includes a representative case of the liberal welfare state regime (United States), of the corporatist or conservative welfare state (Western Germany), of the radical welfare state (Australia), and of the United Kingdom, which is often classified as a liberal country but also shares features of continental European countries (Svallfors Citation1997). The former socialist Hungary and Israel are also included. Furthermore, we provide the overall percentages or mean values in all tables for all countries that took part in the 2016 wave. This is 48,720 respondents from 35 countries (see Edlund and Lindh 2019).

Attitudes toward the role of government over time and across countries

This section summarizes the trends in the items that have been fielded since 1985, which are civil liberties, state intervention in the economy, government spending, and government responsibilities. The presentation of these areas follows the order in the questionnaire and the module description of Jones Edlund and Arvid Lindh (2019). It does not indicate any order of importance or theoretical considerations, rather considerations of questionnaire design.

Civil liberties

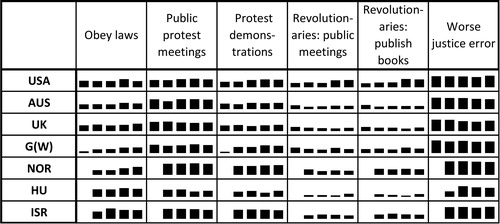

reports, first, the percentage of respondents who chose “Obey the law without exception” over “Follow conscience on occasions.” Second, it reports the percentage of respondents who answered “Definitely” regarding allowing different forms of political actions. Third, the percentage of respondents who selected “Worse mistake: Convict innocent person” over “Let a guilty person go free.” , then, depicts the trends in these answers over time in our selected countries.

FIGURE 1 Attitudes toward civil liberties over time (%).*

*See for the coding of the depicted variables. Bars show these attitudes for the years 1985, 1990, 1996, 2006, and 2016. The right-most bars thus equals the values of . Source: ISSP.

TABLE 1 ROG 2016. Attitudes Toward Civil Liberties (in %)Table Footnote*

The rate of agreement to “Obey laws” is 52.3% when considering all available ISSP countries. Among countries, the lowest rates can be reported for Germany and Australia and the highest for Israel. The trends over time indicate that the rate of agreement was even lower in Germany in the past. Regarding the freedom to protest and other political actions, revolutionaries are the least favored group in all countries. Instead, public meetings are the most welcomed form of political action. Over time, tolerance toward different forms of political actions is rather stable; only an increase in tolerance toward revolutionaries in the United States (the mean increases from 2.5 to 3.1 on a 4-point scale) and a growing support for protest demonstrations in Western Germany (the mean increases from 2.1 to 2.4 on a 4-point scale) stand out. As for convicting an innocent person versus letting a guilty person go free, an overwhelming majority agrees that it would be worse to convict an innocent person (the mean across all available ISSP countries equals 69.4%). When looking at trends over time, a huge jump occurs in Hungary from 1990 to 1996 (from 36.4% to 71.8%), whereas the opinions in the other countries did not change as much.

In analyzing civil liberties and different types of regimes, we expected that the acceptance of different forms of political actions would be the highest in liberal regimes, particularly in the United States. U.S. respondents are indeed the most accepting regarding revolutionaries, but are average regarding public protest meetings and demonstrations. Norwegians, on the other hand, are the most tolerant toward protests. This is a characteristic that also applies to Swedes and Danes in the 2016 survey (but not to Finns). Tolerance toward political actions is also particularly high in many Scandinavian countries.

State intervention in the economy

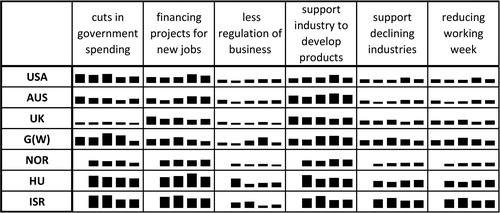

and report attitudes toward various types of state interventions in the economy and their changes over time. Both the table and the figure show the percentage of respondents who are “strongly in favor” of each intervention.

FIGURE 2 Attitudes toward state intervention in the economy over time.*

*See for the coding of the depicted variables. Bars show these attitudes for the years 1985, 1990, 1996, 2006, and 2016. The right-most bars thus equals the values of . Source: ISSP.

TABLE 2 ROG 2016. Attitudes toward State Intervention in the Economy (in %)Table Footnote*

Considering 2016 (see ), around a third of the respondents are strongly in favor of “financing projects for new jobs” and “support industry to develop products,” respectively. “Reducing working week to support more jobs” and “less regulation of business” on the other hand receive the lowest support. At the same time, however, a third of the respondents are also in favor of reducing government spending. Asking for reductions and increases at the same time is particularity common in Israel and Hungary. A more detailed analysis of the entire 2016 sample, however, shows that the correlation between “cuts in spending” and expenditures in the other areas is rather low. We thus observe two different groups within our sample: respondents who would like to see more expenditures and a smaller group of those who would like to see fewer expenditures.

As for changes over time (see ), in many countries preferences regarding state interventions seem to be more volatile than attitudes toward civil liberties (depicted in the previous graph). In Germany, for example, we see an initial increase in the preference for spending cuts in the course of the 1990s followed by a decline in this preference in the 2000s. A similar decline occurs in Israel, where the highest level of agreement occurs in the first waves, followed by a small decline and stabilization.

The volatile nature of these attitudes suggests that people are influenced by the political and economic situation in a country at a given time. Yet, in line with the idea that governmental interventions in the economy should be minimal in liberal countries, U.S. respondents are among those most in favor of cuts in governmental spending and reducing intervention in industry. However, changes over time show that U.S. respondents have become more open to government creating new jobs. In the radical welfare state of Australia we see a similar pattern, although there is less support for cuts in government spending and more consent for state support of industry. In accordance with the social democratic ideal, Norwegians are the least in favor of reducing government spending and lowering business regulation. The West Germans are somewhere in the middle (with the exception of the comparatively low support for state intervention to create new jobs, which could be influenced by the specific unemployment program “Hartz IV”). In addition, the demand for state intervention is still highest in post-socialist Hungary, followed by Israel.

Government spending

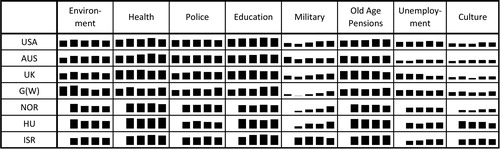

After considering the preferences for state interventions in the economy, and depict attitudes regarding government spending in the areas of education, health, old age pensions, unemployment, culture, environment, the police, and the military. reports the national mean values on a scale of five response categories, with five indicating “Govt. should spend much more” and one that “Govt. should spend much less.” then shows the trends over time.

FIGURE 3 Attitudes toward government spending over time.*

*See for the coding of depicted variables. Bars (range: 1.7 to 4.7) show these attitudes for the years 1985, 1990, 1996, 2006, and 2016. The right-most bars thus equals the values of . Source: ISSP.

TABLE 3 ROG 2016. Attitudes Toward Government Spending (means)Table Footnote*

Health, education, and old age pensions are the most preferred areas of additional government spending in all of our selected countries except for Norway, where police ranks higher than a spending increase for old age pensions. The mean values for these three items are around four, indicating that “government should spend more.” Culture, on the other hand, is the least favored item in all countries except for Israel, where unemployment benefits are considered slightly less important than culture.1 The average values for the least preferred items are between 2.55 and 3.27 and thus between “spend less” and “the same as now.” Furthermore, additional government spending for the unemployed is considered most critical in Australia and the United Kingdom but also in Norway, where unemployment assistance is more extensive than in the previous countries.

As for changes over time (see ), the trends in the preference regarding the military are remarkable. With the exception of Israel—where the preference for this item was very high throughout the entire period—support for higher military spending has increased continuously since 1990. The means of the other variables more or less stagnate over the past ROG waves.

Summing up, the preferences for governmental spending follow the division in different regimes in the sense that neither in the United States, United Kingdom, nor Australia are respondents among the top demanding populations in any of these dimensions. The United Kingdom comes close to the top countries regarding health, which is probably driven by the widely discussed problems of the health care system in Britain. The low demands in Norway could be influenced by the high rate of welfare provisions in the countries and thus might not reflect a general refusal of state intervention.

Government responsibility

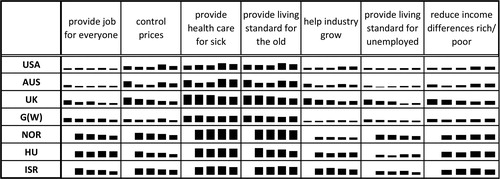

After considering state interventions and expenditures, the final set of items refers to different aspects of government responsibility such as providing jobs and health care. reports the percentage of respondents who answered regarding each item that it “Definitely should be a government responsibility.” shows the changes over time.

FIGURE 4 Attitudes toward government responsibility over time.*

*See for the coding of depicted variables. Bars show these attitudes for the years 1985, 1990, 1996, 2006, and 2016. The right-most bars thus equals the values of . Source: ISSP.

TABLE 4 ROG 2016. Attitudes Toward Government Responsibility (in %)Table Footnote*

Among the different responsibilities, providing health care for the sick and a decent living standard for the elderly receive the strongest agreement in all countries. Yet, the agreement ranges between 49% in the United States to more than 80% in Norway. The preferences across the other items differ considerably across countries. Overall, however, Norwegians are the strongest supporters of various state interventions, followed by Hungarians and Israelis, while the U.S. respondents are among the lowest supporters except for price control and helping industry grow. Australia and the United Kingdom mainly differ from the United States because support for a state-driven health care system is much higher than in the United States. In addition, the views of the West Germans regarding the responsibilities of the government are rather similar to respondents in liberal countries.

Considering changes over time, differences within countries appear to be smaller than the differences across countries. It is interesting to see that British respondents have been lowering their support for all areas over time. They are thus becoming more similar to the liberal U.S. population. The liberal and radical regime countries United States and Australia, on the other hand, are becoming more in favor of providing support for the sick and the elderly.

In sum, the strong support of Norwegians for government responsibility in many areas is in line with the view of a strong Scandinavian welfare state, whereas the U.S. respondents live up to their description as being distant to the welfare state. Germany, on the other hand, offers a diverse picture of medium to low support in various items, with constant low support for industry growth and price control, but more support for assisting the unemployed and reducing income differences between the rich and the poor. The low support for unemployment benefits is particularly surprising and does not match the picture of an all-encompassing conservative welfare state.

Discussion and conclusions

Our contribution started with the assumption that attitudes and views are deeply rooted in the different societal cultures and in a mutual dependency of regimes and attitudes. We thus drew upon classic literature such as Haller et al. (Citation1995), Svallfors (Citation1997, Citation2003), and Ursula Dallinger (Citation2010) and ask whether attitudes are still aligned with the classic regimes types or if economic, cultural, and political changes since 1985 have led to shifts in these patterns.

Corresponding to the classical worlds of welfare regimes (Castles and Mitchell Citation1993; Esping-Andersen Citation1990), the two poles of liberal attitudes and social democratic attitudes are widely confirmed. Citizens in liberal countries are the least in favor of government intervention and business regulations, whereas people in Scandinavia show the highest support for an extensive welfare state that is responsible for all groups in society. In accordance with this classical regime typology, the attitudes of respondents in the corporatist welfare state lie in between these two poles. At the same, as Svallfors had already stated in the 1990s, the UK respondents are still a remarkable and unclear case, sometimes close to the liberal countries (such as in the preference for unemployment assistance) but sometimes not (e.g., in health care). Overall, however, UK respondents seem closer to the liberal pattern when taking into account their preferences regarding government responsibilities.

Of course, this picture of alignment between attitudes and regimes is simplified. Going into more detail, we can observe deviating cases from the dominant pattern: Hungary and Israel do not fit into the Western pattern, given that the preference for state intervention is particularly high in both countries. The attitudes of West Germans are sometimes closer to those of respondents from liberal welfare states—possibly due to the implementation of third-way policies in Germany over the last decades. U.S. citizens, on the other hand, have become more open to the government creating jobs and providing support for the sick and elderly, which could have been affected by the debate around general health care and public insurance.

Furthermore, an interpretation of the associations between regimes and preferences should also consider the actual level of expenditures (see also Dallinger Citation2010). Norwegians and other Scandinavians, for example, have a low preference for additional government spending. Yet, state provision is the highest in Scandinavia and respondents thus may not favor even more redistribution, but may still be in agreement with the high level of existing expenditures.

Our analysis also shows that the support for civil liberties is the most pronounced in Scandinavia and not as expected in liberal welfare states such as the United States. A possible explanation for this finding is that social democratic state intervention is often mistaken for minimizing individual liberties. In contrast, social democracy means that individual liberties should be distributed equally—a universal and maximum of personal freedom should be achieved in societies (Brandal, Bratber, and Thorsen 2013).

Finally, as for our research question of whether attitudes and values have changed considerably, given the breakdown of the socialist system in Eastern Europe and increasing deregulation, we can conclude that attitudes and opinions are rather persistent. This finding indicates that historically grown values regarding the role of the state and the market are deeply rooted in the culture of societies. Our analysis, however, is limited to the societal level. The consideration of differences within countries, e.g., between the more and less prosperous, thus would allow for additional insights into the stability of values and attitudes.

Additional information

Markus Hadler is a professor of sociology at the University of Graz, Austria, and an honorary professor in the Department of Sociology, Macquarie University, Australia. He is also Austrian representative to the International Social Survey Program (ISSP). His research interests lie in the areas of social inequality, political sociology, and environmental sociology.

Christian Mayer currently works as a research assistant for the Department of Sociology at the University of Graz, Austria, and in teacher training. His main research interests include social inequality, political sociology, and sociology of education.

Anja Eder is a researcher in sociology at the University of Graz, Austria. She works in the fields of social inequality and political sociology in international comparison. She is a founding member of the Center for Empirical Methods of the Social Sciences at the University of Graz and a member of the ISSP.

Notes

1 Differences are smaller when considering only the percentage of “spend more” responses.

References

- Abercrombie, Nicholas. . 1990. “Popular Culture and Ideological Effects.” Pp. 199–228 in Dominant Ideologies, edited by N. Abercrombie, S. Hill, and Bryan S. Turner. . New York: Routledge.

- Arts, Wil, and John Gelissen.. 2001. “Welfare States, Solidarity and Justice Principles: Does the Type Really Matter?” Acta Sociologica 44(4):283–99. doi: 10.1177/000169930104400401.

- Brandal, Nik, Øivind, Bratber, and Dag Einar Thorsen. . 2013. The Nordic Model of Social Democracy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brooks, Clem, and Jeff Manza.. 2006. “Why Do Welfare States Persist?” Journal of Politics 68(4):816–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00472.x.

- Castles, Francis G., and Deborah Mitchell.. 1993. “Worlds of Welfare and Families of Nations.” Pp. 93–128 in Families of Nations: Patterns of Public Policy in Western Democracies, edited by Francis G. Castles. . Aldershot, UK: Dartmouth.

- Dallinger, Ursula. . 2010. “Public Support for Redistribution: What Explains Cross-National Differences?” Journal of European Social Policy 20(4):333–49. doi: 10.1177/0958928710374373.

- Eder, Anja. . 2017. “Public Support for State Redistribution in Western and Central Eastern European Countries. A Cross-National Comparative Trend Analysis.” Pp. 81–101 in Social Inequality in the Eyes of the Public. A Collection of Analyses Based on ISSP Data 1987-2009, edited by J. Edlund, I. Bechert, and Markus Quandt. . Cologne, Germany: Gesis.

- Edlund, Jonas, and Arvid Lindh. . 2019. “The ISSP 2016 Role of Government Module: Content, Coverage, and History.” International Journal of Sociology 49(3). In print.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. . 1990. Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Fenger, H. J. Menno. . 2007. “Welfare Regimes in Central and Eastern Europe: Incorporating Post-Communist Countries in a Welfare Regime Typology.” Contemporary Issues and Ideas in Social Sciences 3(2):1–30.

- Haller, Max, Mach Bogdan, and Heinrich Zwicky.. 1995. “Egalitarismus und Antiegalitarismus zwischen gesellschaftlichen Interessen und kulturellen Leitbildern. Ergebnisse eines internationalen Vergleichs.” Pp. 221–64 in Soziale Ungleichheit und Soziale Gerechtigkeit, edited by Hans-Peter Müller and Bernd Wegener. . Wiesbaden, Germany: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kollmorgen, Raj. . 2009. “Postsozialistische Wohlfahrtsregime in Europa–Teil der “Drei Welten” oder eigener Typus?” Pp. 65–92 in International Vergleichende Sozialforschung. Ansätze und Messkonzepte Unter den Bedingungen der Globalisierung, edited by B. Pfau-Effinger, M. S. Sakac, and Christof Wolf. . Wiesbaden, Germany: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Powell, Martin, and Armando Barrientos.. 2004. “Welfare Regimes and the Welfare Mix.” European Journal of Political Research 43(1):83–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00146.x.

- Sachweh, Patrick. . 2010. Deutungsmuster Sozialer Ungleichheit. New York: Campus.

- Svallfors, Stefan. . 1997. “Worlds of Welfare and Attitudes to Redistribution: A Comparison of Eight Western Nations.” European Sociological Review 13(3):283–304. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018219.

- Svallfors, Stefan. . 2003. “Welfare Regimes and Welfare Opinions: A Comparison of Eight Western Countries.” Pp. 171–96 in European Welfare Production. Institutional Configuration and Distributional Outcome, edited by Joachim Vogel. . Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.