Abstract

Previous studies have shown that institutional trust is associated with people’s support for some environmental policies (e.g., support for higher taxation) but not others (e.g., support for subsidies and bans). Such findings seem to contradict the notion that institutional trust helps to resolve social dilemmas and thus facilitates collective action on environmental problems. In the current study, we use the conceptual framework of the attitudinal theory of the Campbell paradigm to understand the lack of institutional trust as a behavioral cost of policy support which counterweights people’s motivation to support a policy. Using a dataset from the Environmental module of a recent ISSP survey conducted in 28 countries, we corroborated the theoretical prediction, namely the expected positive effect of institutional trust on support for both pro- and anti-environmental policies. We also corroborated, albeit with some qualifications, that the choice of environmental policy depends on perceived behavioral costs exemplified, in our study, by institutional trust. The Campbell paradigm provides a useful analytical framework for understanding the role of trust in environmental policy support. It also helps us to understand previous inconsistent findings regarding the effect of trust on environmental policy support.

Popular support for environmental policies is critical for the sustainable transformation of our societies (Ostrom, Citation2009). A lack of popular backing can hinder the adoption of sustainable policies, and weaken their effectiveness once adopted (Anderson et al. Citation2017; McGrath & Bernauer, Citation2017; Tjernström & Tietenberg, Citation2008; Wiseman et al. Citation2013). Failure of support may also trigger pushback movements threatening to reverse any progress toward sustainability (Douenne & Fabre, Citation2022; Patterson, Citation2023). Building support for sustainable policies has therefore become one of the most important goals of interventions aimed at changing individual pro-environmental behavior (Hampton & Whitmarsh, Citation2023).

One of the factors positively associated with environmental policy support is trust (e.g., Kukowski et al. Citation2023; F. Wang et al. Citation2024). However, the relationship between trust and environmental policy support is not universal and is missing in some contexts (e.g., Faure et al. Citation2022; Zhang et al. Citation2022). In the present study, we use the theoretical framework of the attitude theory of the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al. Citation2010; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019) to understand the role of institutional trust in individuals’ decision making regarding support for pro-environmental policies and the choice of an optimal pro-environmental policy. This theoretical perspective can explain observed inconsistencies in the role of trust in environmental policy support and link the role of trust to the decision-making process. More broadly, this study demonstrates how trust can be integrated into a model of pro-environmental behavior and generate useful predictions about the effects of trust on policy support and the choice of optimal environmental policies.

The Campbell paradigm

The Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al. Citation2010; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019) builds on the classical notion of attitude as a tendency to respond in a certain way to attitude objects (Allport, Citation1935). This attitude conception is one of the two dominant attitude frameworks in sociology (Pestello, Citation2007) and is common to many recent attitude theories (e.g., Ajzen, Citation1991; Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1993). More specifically, it builds on the notion that attitude is manifested in the form of affective, cognitive, and behavioral reactions (Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019; see also Rosenberg & Hovland, Citation1960).Footnote1 The notion that attitude can be estimated from behavioral responses may seem puzzling, but it is consistent with the positivist notion of attitude as a latent tendency to respond to an attitude object in a certain way (Allport, Citation1935). Consequently, it is legitimate, within this tradition, to use behavioral indicators to infer attitude and then inquire how this attitude predicts logically unrelated (i.e., with different content) but attitude-relevant behaviors (e.g., pro-environmental attitude inferred from self-reports of ecological behavior can be used to predict support for environmental policies, e.g., Gerdes et al. Citation2023; Kaiser et al. Citation2023; Urban et al. Citation2021). The term teleological relationship (rather than causal) is sometimes used to emphasize the relationship between latent behavioral tendency and manifest behavior in such a prediction (Kaiser et al. Citation2010). The idea that environmental attitude can be inferred from affective, behavioral and cognitive responses has been explicitly formulate in some environmental attitude measures (e.g., Maloney & Ward, Citation1973) and implicitly present in others (e.g., Franzen & Vogl, Citation2013; Mayerl & Best, Citation2018, Citation2019).

Campbell’s paradigm is based on the assumption that individual pro-environmental behavior is a function of a person’s environmental attitude levels and the difficulty of a given pro-environmental behavior, which affects engagement probability negatively (Kaiser et al. Citation2010; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019). In other words, an individual engages in a given pro-environmental behavior only if their environmental attitude is strong enough to overcome the behavioral costs associated with a specific behavior. Both environmental attitude and behavioral costs are latent factors that are estimated through a Rasch measurement model (for details of the model, see Bond & Fox, Citation2012). The Campbell paradigm was originally proposed as a theoretical framework to explain the pro-environmental behavior of individuals (Kaiser et al. Citation2010). Over time it has been validated in many other contexts, for example, attitudes to climate change and climate change policies (Urban, Citation2016; Urban et al. Citation2021), health-related behavior (Byrka & Kaiser, Citation2013), and conformity (Brügger et al. Citation2019).

Under the Campbell paradigm, behavioral costs are assumed to be constant across individuals in a given population (Kaiser et al. Citation2010). However, they can and typically do differ across populations (Kaiser & Biel, Citation2000; Kaiser & Keller, Citation2001). Behavioral costs associated with pro-environmental behavior potentially include a wide range of costs (besides the obvious financial costs, there may also be non-financial costs such as transaction, search, opportunity, and time costs, as well as other types of costs). While the assumption of constant behavioral costs of a specific behavior is a useful simplification that allows for the estimation of the Rasch model (i.e., it makes the model identifiable by separating person-specific attitude and behavior-specific cost), it is probably not realistic to expect that all the behavioral costs of pro-environmental behavior are constant in a given population. As we shall see in the next two sections, lack of institutional support as one of the potential behavioral costs of pro-environmental behavior can vary across individuals in a given population.

The Campbell paradigm is one of many existing behavioral models that have been used as an explanation of pro-environmental behavior in sociology (for an overview, see, e.g., Liebe, Citation2010; Telesiene & Hadler, Citation2023; Tian & Liu, Citation2022). These models include the theory of planned behavior (for a review, see Yuriev et al. Citation2020), value-belief-norm theory (e.g., Al Mamun et al. Citation2022; Batool et al. Citation2023; Stern et al. Citation1999), health belief model (e.g., Castellini et al. Citation2023; Kim & Cooke, Citation2021), protection motivation theory (e.g., Bockarjova & Steg, Citation2014; Rainear & Christensen, Citation2017; Shafiei & Maleksaeidi, Citation2020). These models have inspired attempts to create even more complex and more synthetic models through their combination (e.g., Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Klöckner, Citation2013; Savari et al. Citation2023; Y. Wang et al. Citation2019). The notion, present in the Campbell paradigm, that pro-environmental behavior is affected by attitude (specifically attitude to environmental protection or pro-environmental attitude) is shared with several of these models such as the theory of planned behavior (Kaiser et al. Citation2005), the value-belief-norm model (attitude is represented in VBN model with ecological worldview Stern et al. Citation1999) and the synthetic models that have identified the most prominent factors of pro-environmental behavior (e.g., Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Klöckner, Citation2013). What distinguishes the Campbell paradigm from many other models of pro-environmental behaviors is its recognition of behavioral costs (objective situational constraints) as factors in pro-environmental behavior. Such objective situational constraints are either omitted in other behavioral models such as the value-belief norm model (e.g., Stern et al. Citation1999) and Bamberg and Möser’s (Citation2007) synthetic model, or they enter the model indirectly as perceived constraints (perceived behavioral control) in the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) and Klöckner’s (Citation2013) synthetic model. As we will show in the next section, the concept of behavioral costs that capture contextual constraints on behavior allows us to focus on additional contextual factors known to affect pro-environmental behavior, such as institutional trust.

Lack of trust as a behavioral cost within the Campbell paradigm

Trust, typically defined as a “feeling of confidence” toward some entity (Smith & Brooks, Citation2013), is known to reduce transaction costs in interactions between individuals and groups by reducing the need for monitoring, producing, and enforcing contracts (Bunduchi, Citation2008; Dyer & Chu, Citation2003).Footnote2 By reducing these and other behavioral costs, trust fosters cooperation between individuals and groups (Acedo-Carmona & Gomila, Citation2014; Bellemare & Kröger, Citation2007; Gächter et al. Citation2004; Poteete et al. Citation2010; Rothstein, Citation2005). As an exception to this rule, there are some situations where trust does not promote cooperation. For instance, Bauer et al. (Citation2019) found that trust in an entity does not predict willingness to reveal personal information requested by the entity. Likewise, Glaeser et al. (Citation2000) found that stated trust toward a subject did not predict trusting behavior in the laboratory trust game.

These seemingly conflicting findings can be explained within the Campbell paradigm: lack of cooperative behavior among people with high levels of trust can be expected in situations when these people have very low motivation to act (low level of attitude toward the target behavior) or when the total behavioral costs are still prohibitively high, even if trust increases (for instance, there might be important monetary cost or personal consequences of a given behavior).

Role of trust in policy support and policy preference

Support of pro-environmental policies is a type of pro-environmental behavior with indirect but potentially large consequences for environmental protection (Stern, Citation2000). The adoption of any legal norm requires the coordinated effort of a large number of individuals (sometimes even the support of the majority of the active electorate) and thus depends on the cooperation of others. Given these features of policy support, it is not surprising to find trust to be an important condition of any policy support and compliance with that policy (Dincecco, Citation2017; Tyler, Citation2006).

These observations suggest that lack of trust constitutes an important behavioral cost of policy support. Conversely, an increase in trust (which reduces behavioral costs) should lead (everything else—namely the motivation of people—constant) to increased policy support. Indeed, there is strong evidence that trust, especially institutional trust, increases environmental policy support (Rhodes et al. Citation2017; F. Wang et al. Citation2024). Importantly, it is not just trust in government but also trust in other entities such as scientists and environmental groups that is positively associated with support for environmental policies (Cologna & Siegrist, Citation2020; Dietz et al. Citation2007; Rhodes et al. Citation2017). Of note is that the positive association between trust and environmental policy support is missing in some areas. For instance, trust in government was found to be weakly related to support for environmental subsidies and bans but more supportive of taxes (Davidovic & Harring, Citation2020; Zhang et al. Citation2022). Likewise, support for an increase in CO2 tax was found to be unrelated to people’s generalized trust (Hammar & Jagers, Citation2006). Trust was also found to be unrelated to support for limits on energy consumption and the introduction of environmental education and information campaigns (Faure et al. Citation2022).

Such discrepancies are consistent with the theoretical framework of the Campbell paradigm: we can expect that trust is largely unrelated to policy support in situations where people have extremely positive or negative attitudes toward the policy (so that their level of trust does not change their decision whether to support the policy or not) or when other behavioral costs dominate in the policy support.

Predictions

Based on the theoretical framework of the Campbell paradigm, we predict that support for environmental policies will be positively affected by a person’s environmental attitude and institutional trust, which in our case captures one of the important behavioral costs of policy support. We also predict that support for anti-environmental policy will be negatively affected by environmental attitude but positively affected by institutional trust, as trust represents behavior cost for any type of policy support, regardless of whether this policy is pro- or anti-environmental.

We predict that when people choose optimal environmental policies to solve societal problems, they select such policies that have a chance to overcome the behavioral costs that most people face. For instance, in a situation of low institutional trust, they should choose policies that do not require the voluntary collaboration of others and require relatively less oversight and institutional backing. More broadly, we predict that the choice of the optimal will vary with the perceived level of institutional trust.

Study objectives

The aim of this study was to explore the role of institutional trust as a factor of environmental policy support and the choice of optimal environmental policy. Specifically, building on the theoretical framework of the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al. Citation2010; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019), we understood the (lack of) institutional trust as a behavioral cost of policy support and hypothesized that institutional trust increases support for both pro- and anti-environmental policies. We also predicted that environmental attitude (i.e., people’s environmental motivation) increases support for pro-environmental policies but decreases support for anti-environmental policies. Elaborating on the notion of institutional trust as a behavioral cost of policy support, we expected that people’s perception of the behavioral costs of policy support (exemplified by their institutional trust) determines what policies people see as optimal to make businesses and individuals protect the environment. We tested these predictions on a dataset from the Environmental module of a recent ISSP survey that covers 28 countries (ISSP Research Group, Citation2023).

Method

Participants

For our study, we used a freely available dataset from the environmental module of the ISSP survey (ISSP Research Group, Citation2023).Footnote3 Simple random sampling and stratified random sampling were used to collect samples of adult populations in 28 countries. The data collection modes varied across the countries and ranged from self-administered questionnaires to telephone interviews and face-to-face interviews. The final sample consisted of 37,472 participants of which 19,420 (52%) were women and the average age of participants was 49 years (SD = 17). The national samples had between 956 (New Zealand) and 3,864 (Switzerland; see in the Appendix for details of national samples) participants.

Materials

Independent variables

Institutional trust

We measured institutional trust with four items that tapped into trust in university research centers, the news media, business and industry, and national parliaments. Similar evaluative measures of institutional trust are widely used, particularly in cross-cultural surveys (OECD, Citation2017). Participants indicated their trust in each of the four entities on an eleven-point scale with labeled endpoints (0 = no trust at all, 10 = complete trust). The scale had a high internal consistency reliability across the countries, α = .58 (Spain)– .86 (Slovakia); α > .70 in 21 out of 28 national samples. We computed a mean score from the four items prior to analysis, with means ranging between 4.05 (Russia) and 6.92 (China), and standard deviations between 1.42 (South Korea) and 2.37 (Slovakia).

Environmental attitude

Following the logic of the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019), we constructed our measure of environmental attitude based on cognitive, affective, and behavioral attitude-relevant responses available in the dataset. We identified 18 cognitive items (e.g., rating of the importance of environmental issues), 7 behavioral items (e.g., self-reported frequency of air travel), and only one item with an affective component (rating of one’s concern about climate change), for the total of 26 items (see the in the Appendix for details of items and their coding).

We calibrated the scale using the Rasch measurement model (for details of model estimation, see Andrich & Marais, Citation2019; Bond & Fox, Citation2012). Specifically, we used a Rasch model for dichotomous responses. Before we could do this, we dichotomized responses to the 26 attitude items (for details, see in the Appendix). Such item dichotomization has been shown to reduce measurement error in similar scales (Kaiser & Lange, Citation2021).

and, in addition, has the advantage of allowing for the use of a simplified dichotomous Rasch model (de Boeck & Wilson, Citation2011). The person separation reliability (an analog of scale reliability in classical test theory) ranged between .58 (India) and .86 (United States) and was larger than .70 in 24 out of the 28 countries. Examination of item fit indices revealed a good fit of items to the data, Infit MS = 0.74–1.19 (i.e., with less than 20% excess random variation in the measure). Such a measure predicts attitude response patterns observed in the data very well (Wright & Linacre, Citation1994).

Dependent variables

Environmental policy support

We used four indicators of policy support available in the dataset. Three of the indicators captured support for pro-environmental policies, namely support for environmental policies increasing taxes (“How willing would you be to pay much higher taxes in order to protect the environment?”) and prices (“How willing would you be to pay much higher prices in order to protect the environment?”), and support for environmental policies resulting in cuts in living standards (“How willing would you be to accept cuts in your standard of living in order to protect the environment?”). The fourth indicator measured support for a potentially anti-environmental policy of opening natural preserves to economic development (“How willing would you be to accept a reduction in the size of [COUNTRY’s] protected nature areas, in order to open them up for economic development?”). For each of the four items, participants indicated their support for a given policy on a five-point scale (1 = very willing, 2 = fairly willing, 3 = neither willing nor unwilling, 4 = fairly unwilling, 5 = very unwilling). We reverse-coded the four indicators so that higher scores indicated higher policy support.

Choice of optimal environmental policy

We used two items available in the dataset to capture the choice of optimal policy to make businesses and individuals protect the environment. For each of the items, participants could choose one of the following policies: (i) heavy fines for businesses (or people) who damage the environment; (ii) use of the tax system to reward businesses (or people) that protect the environment; (iii) provision of more information and education for businesses (or people) about the advantages of protecting the environment; or (iv) participants could self-identify as undecided.

Results

Policy support

Support for each of the policies expressed on the five-point scale (with higher values indicating higher support) varied considerably across the countries (). Specifically, the average support for higher prices ranged between 1.98 (Slovakia) and 3.73 (India), support for higher taxes ranged between 1.87 (Russia) and 3.54 (India), support for cuts in one’s standard of living ranged between 2.12 (Slovakia) and 3.65 (China), and the support for opening up nature preserves to economic development ranged between 1.45 (France) and 3.19 (India).

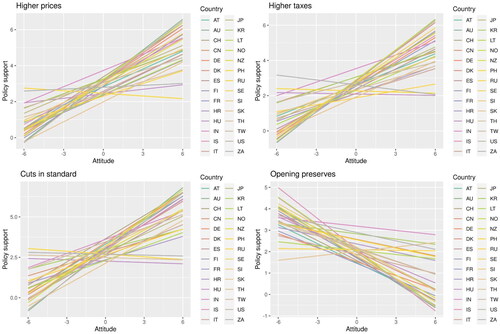

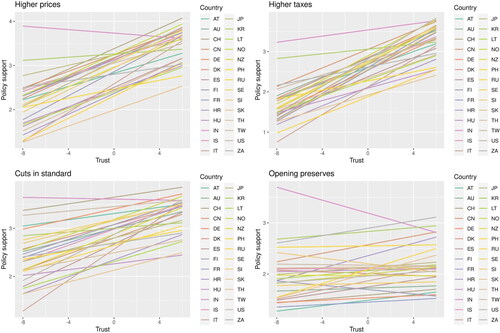

Next, we fitted four mixed regression models each with one type of policy support as the dependent variable and attitude and trust scores as independent variables (fixed effects), thus allowing for random intercepts across countries and random effects of attitude and trust across countries. This analysis revealed that environmental attitude had, on average, the expected positive effect on the acceptance of the three pro-environmental measures and the expected negative effect on the acceptance of anti-environmental measures (opening of nature preserves to economic development) across the countries (see for details). We also found that institutional trust had the expected positive effect on all four policy measures. These results corroborated the predictions derived from the Campbell paradigm.

Further scrutiny of the mixed model revealed a relatively large variance of random intercepts, revealing the varying acceptability of policy measures across countries. Relatively small variances in random effects of both attitude and trust suggested that the effects of attitude and trust were relatively similar across countries. We arrived at the same conclusion when we examined country-specific model-predicted policy support (see and and in the Appendix). This analysis revealed a consistent positive effect of environmental attitude on the three indicators of pro-environmental policy support (higher prices, higher taxes, and cuts in standard of living) and a negative effect on the opening of preserves to economic development; these effects were quite consistent across countries. Out of the 112 attitude effects estimated in the mixed model (28 countries × 4 DVs), we observed only 9 instances (8%) of estimated attitude effects that violated theoretical expectations. Likewise, we observed only 5 instances (4%) of trust effect estimates that violated the theoretical expectation.

Given that interclass correlations in each of the four mixed models were low (ICC = .12–.16), there was relatively little “pooling” of estimates in mixed models (Gelman & Hill, Citation2007) across countries. In other words, country-specific regression models should reveal very similar patterns as the mixed model. This was, indeed, the case: country-specific models fitted separately in each of the countries and revealed a positive effect of environmental attitude on acceptance of pro-environmental policies and a negative effect on acceptance of anti-environmental policy ( in Appendix). Likewise, these analyses revealed a positive effect of institutional trust on acceptance of all policies (regardless of whether these were pro- or anti-environmental). Of note is that, as with the mixed effect model, these patterns held across the countries. We observed 7 (6%) deviations in attitude effects and 3 (3%) deviations in trust effects from theoretically expected patterns.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis by including socio-demographic indicators and an indicator of the left-right political orientation (see in Appendix for details). This analysis found that adding these variables improved explained variance only marginally (by 0.5–2.1 percentage points, marginal R2) and did not substantially change the results regarding the role of environmental attitude institutional trust. These sensitivity checks revealed a negligible positive effect of education, mixed effect of age, mixed effect of gender, mixed effect of social status, and no effect of left-right political orientation.

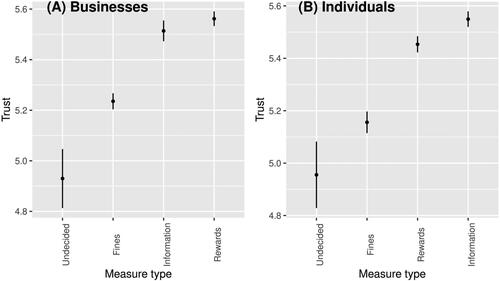

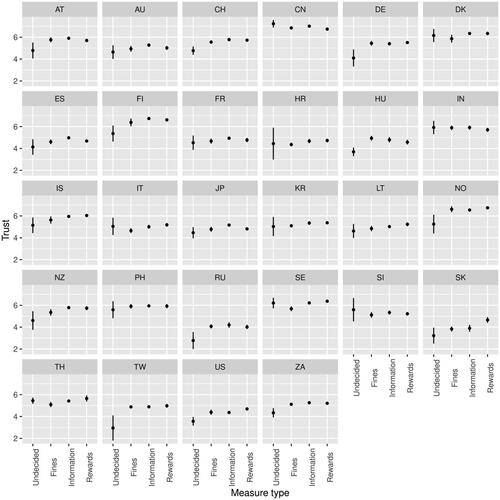

Choice of optimal policy for business

The choice of the optimal policy to make businesses protect the environment varied considerably across the countries (see ). The largest group of people (19.85%–53.03%) proposed fines, followed by rewards (19.69%–54.22%) and information provision (10.31%–37.94%), whereas the remaining group of people (1.22%–7.40%) was undecided. As expected, an ANOVA analysis with polynomial contrasts fitted on the pooled sample revealed that people who chose different policy strategies had different levels of institutional trust, F(3,37468) = 110.81, p < .001. Furthermore, this analysis revealed a significant linear trend, F(1, 37468) = 298.69, p < .05, whereby undecided people had the lowest level of institutional trust, followed by people who chose fines, people who chose information provision, and—finally—people who chose rewards and who had the highest level of institutional trust ().

Figure 1. Average levels of institutional trust in people proposing alternative measures to ensure environmental protection by businesses and individuals (pooled sample, means, and their 95% CIs).

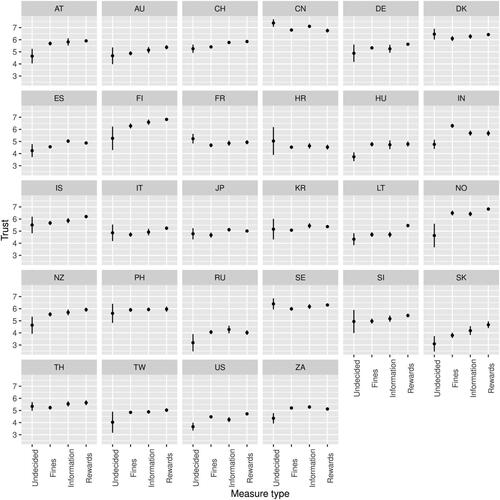

Next, we tested whether we could replicate these results in each of the national samples. Grouped ANOVA with polynomial contrasts revealed that average levels of institutional trust were different across people who chose different policy measures in 24 out of 28 countries (α = .05; for details, see in Appendix). Moreover, the same analysis revealed a statistically significant linear trend, the same that we found with the pooled sample, in 20 out of the 28 countries (see in Appendix for details; see also in Appendix).

Choice of optimal policy for individuals

Again, the choice of the optimal policy to make individuals protect the environment varied considerably across the countries ( in Appendix). The most frequently proposed measures to motivate individuals to protect the environment were rewards (21.14%–53.95%), followed by information provision (18.32%–50.75%), and fines (8.68%–47.06%); the remaining (0.68%–10.19%) were undecided people. As expected, an ANOVA analysis with polynomial contrasts revealed differences in institutional trust between people who chose different strategies to make individuals protect the environment, F(3, 37468) = 105.88, p < .001. The linear trend of increasing institutional trust across policy options for individuals was similar to that for businesses, except that this time people who chose rewards had the second highest and people who chose information provision had the highest level of institutional trust, F(1, 37468) = 292.48, p < .001 (see also ).

Next, we again tested whether we could replicate these results in each of the national samples. Grouped ANOVA with polynomial contrasts revealed that average levels of institutional trust were different across people who chose different policy measures in 24 out of 28 countries (see in Appendix for details). The same analysis also revealed a statistically significant linear trend, the same that we found with the pooled sample, but in only 15 out of the 28 countries (see in Appendix for details; see also in Appendix).

Discussion

In our study, we used the theoretical framework of the theory of the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al. Citation2010; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019) to examine the role of trust as a factor of environmental policy support and the choice of optimal environmental policy. This theoretical framework suggests that people support environmental policy if their attitude toward the policy outweighs the behavioral costs associated with the given policy. One of the important behavioral costs of policy support is related to the lack of institutional trust (Dincecco, Citation2017; Tyler, Citation2006). We predicted that whereas institutional trust is positively related to any kind of policy support, people’s environmental attitude is positively related to support for pro-environmental policies and negatively to their support of anti-environmental policies. We also hypothesized that when choosing an optimal policy to address an environmental problem, people choose policies that can overcome obstacles they think most people face. In other words, they would choose policies as a function of their perceived behavioral costs, represented in our study by institutional trust.

Using a cross-cultural dataset from the Environmental module of the ISPP survey (ISSP Research Group, Citation2023) covering 28 countries, we were able to corroborate the positive statistical effect of environmental attitude on support for pro-environmental policies (support for policies that improve environmental protection by increasing prices, taxes or by cuts in standard of living) and its negative effect on support for anti-environmental policy (support for a policy that opens nature preserves to economic development). Further, we also corroborated the expected positive effect of institutional trust on support for both pro- and anti-environmental policies. Notably, these results were mostly consistent across the four policies and 28 countries.

We also corroborated the notion that people choose an optimal environmental policy to ensure the protection of the environment by businesses or individuals as a function of the behavioral costs they foresee for the policy, exemplified in our study by (a lack of) institutional trust. Specifically, we observed that people choose optimal environmental policy as a function of their institutional trust. People with the highest levels of institutional trust selected tax rewards and information provision as the most optimal policies. Arguably, these policy measures rely most on the cooperation and “goodwill” of others and thus are feasible only when one perceives behavioral costs as rather small (i.e., expresses a high level of institutional trust). Those with lower levels of trust opted for fines, which can arguably enforce cooperation rather than rely on the goodwill of others. Finally, people with the lowest levels of institutional trust were unable to identify the optimal policy and declared themselves undecided, perhaps because they perceived that none of the policy options would overcome the barrier exemplified by the low level of institutional trust.

Theoretical and practical implications

Finding institutional trust and environmental attitude to be positively associated with environmental policy support is not novel. Many previous studies have observed the same pattern (Cologna & Siegrist, Citation2020; Davidovic & Harring, Citation2020; Dietz et al. Citation2007; Fairbrother et al. Citation2019; Faure et al. Citation2022; Hammar & Jagers, Citation2006; Kukowski et al. Citation2023; F. Wang et al. Citation2024). This study contributes to the literature on environmental policy support by conceptualizing (a lack of) institutional trust as a behavioral cost of policy support (another example of how other types of behavioral costs of environmental policy support can be studied using the Campbell paradigm is provided by Gerdes et al. Citation2023). The inclusion of behavioral costs in models of pro-environmental behavior is relatively rare (e.g., Stern et al. Citation1999; Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Klöckner, Citation2013) despite the evidence that behavioral costs affect various types of pro-environmental behavior (and related outcome variables, such as intention; Kaiser et al. Citation2021; Kaiser & Lange, Citation2021; Mayerl & Best, Citation2019). More broadly, this study demonstrates how the Campbell paradigm can be used to theoretically justify measures of environmental attitude based on behavioral, cognitive, and affective indicators frequently used by sociologists (e.g., Franzen & Meyer, Citation2010; Franzen & Vogl, Citation2013; Mayerl & Best, Citation2018, Citation2019; Urban, Citation2016; Urban & Kaiser, Citation2022). This is in contrast to the other widely used measure of environmental attitude in sociology, the New Environmental Paradigm Scale (Dunlap, Citation2008; Dunlap & Van Liere, Citation1978), which is not theoretically grounded in attitude theory. The relative parsimony of the Campbellian framework compared to other models of pro-environmental behavior may be seen as overly simplistic, but it also helps to guard against mistakenly interpreting random noise in the data as an actual signal (i.e., overfit) and allows for better generalization of the model to new data (Pitt & Myung, Citation2002; Silver, Citation2013).

The findings of the current study have some interesting implications. One is that we should expect institutional trust to make any policy more acceptable by decreasing its behavioral costs, even policies that harm the environment, as we have also seen in the current study. The fact that a policy is pro-environmental does not make it more likely, from the theoretical point of view, that institutional trust will increase its acceptance. This view goes against the notion present in some previous studies that viewed the pro-environmental quality of policies to be related to institutional trust (e.g., Davidovic & Harring, Citation2020; Fairbrother, Citation2016; Fairbrother et al. Citation2019).

The second implication of this perspective is that the association between institutional trust and policy support may become very weak in situations when people’s attitudes toward the policy are either extremely negative or extremely positive. In such situations, varying behavioral costs will change the acceptance of the policy very little. Likewise, the existence of other and perhaps more important behavioral costs (e.g., financial costs) may make some policies so unattractive that even high levels of institutional trust will not make the policy acceptable. This theoretical consideration could potentially explain the lack of association between institutional trust and environmental policy support observed in some studies (e.g., Davidovic & Harring, Citation2020; Faure et al. Citation2022).

Third, the Campbellian framework also provides a good starting point when one wishes to understand how people choose optimal policies to solve a certain environmental problem. Given that lay people use heuristics resembling the logic of the Campbell paradigm, where they infer the environmental motivation of others from their actions (Braun Kohlová & Urban, Citation2020; Urban et al. Citation2023) and the difficulty of this action (van der Werff et al. Citation2014), they likely use the same heuristics when they choose the optimal environmental policy. Namely, it is likely that people select a policy that has a good chance of overcoming the behavioral barriers that face the individuals who will adopt this policy. In other words, we may expect that different policies will be preferred as perceived behavioral costs increase. The current study found some preliminary evidence of such a mechanism, but further exploration of this phenomenon is warranted.

Limitations of the Campbell paradigm

Although the present study builds theoretically on the Campbell paradigm, it also highlights the potential limitations of this theory. Most notably, the current study implicitly questions the notion of behavioral costs that are constant—for a given behavior—across individuals within a given population present in the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al. Citation2010, Citation2021; Kaiser & Biel, Citation2000; Kaiser & Keller, Citation2001). By showing that institutional trust, which is highly variable across individuals in each national sample, affects policy support, the current study demonstrates that at least some of the behavioral costs (exemplified by institutional trust in our study) are not constant in a population. This notion is mirrored in other behavioral theories that also assume the existence of individual-specific factors obstructing behavior (e.g., Simon, Citation1955; Verhallen & Pieters, Citation1984). We think that the problem lies with the confusion of the two roles of the Campbell paradigm, as a measurement model and as a behavioral-predictive model (e.g., Kaiser et al. Citation2021; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019). While invariance of behavioral costs is probably necessary for measurement models for technical reasons (i.e., we need to construct measures with invariant item difficulties), it is not realistic to postulate such invariance in behavioral costs for every behavior that we aim to explain empirically.

Another question that follows from our study is how we can integrate different behavioral costs within the Campbell paradigm. In its role as a measurement theory, the Campbell paradigm estimates implicit behavioral costs from observed responses (e.g., Bauske et al. Citation2022; Urban & Braun Kohlová, Citation2020; Urban & Kaiser, Citation2022). However, when used as a predictive model, one can measure the behavior costs (or their part) externally and relate them to the behavior that is being explained, as we have done with institutional trust and policy support in our study (for another example of how externally measured costs can be used to predict behavior within the Campbell paradigm, see Gerdes et al. Citation2023; Kaiser & Lange, Citation2021). When measured externally, the question arises as to how to aggregate different behavioral costs when we wish to predict the behavior. While our study does not answer this question, it shows that measuring specific aspects of behavioral costs (such as institutional trust in the current study) is useful when we want to predict environmental policy support.

Limitations of the present study

Given the correlational nature of the evidence reported in the present study, it cannot fully establish the causal relationship between institutional trust and policy environmental support. Causal evidence on the role of institutional trust as a factor of policy support is extremely rare (Spadaro et al. Citation2020). Even if the measure of institutional trust used in the present study is rather general and does not semantically overlap with the measure of policy support, we cannot rule out that the association observed between institutional trust and policy support in the current study is inflated due to common method bias (Kock et al. Citation2021). The logical next step of a follow-up study would be to use experimental manipulation of institutional trust to demonstrate its effect on support for pro- and anti-environmental policies.

Another limitation of the present study lies in the fact that it uses intention-based measures of policy support and that there are only a few policies covered and these policies are rather general. This limitation comes with most multi-country surveys, such as ISSP, that aim to gather comparative evidence in different countries and cultural contexts. Future studies would benefit from targeting a more varied sample of policies by increasing the consequentiality of their measures (for instance by making these measures incentive compatible) or by measuring actual policy support (for examples of incentivized and consequential behavioral tasks, see, e.g., Lange, Citation2022).

Conclusions

Using a dataset from a survey conducted in 28 countries and building on the theory of the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al. Citation2010; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2019), we found that a lack of institutional trust is a behavioral cost that reduces the support for both pro-environmental and anti-environmental policies. As expected, we also found that people’s environmental attitude increases their support for pro-environmental policies but decreases support for anti-environmental policies. When choosing an optimal environmental policy to make businesses and individuals protect the environment, people choose policies as a function of behavioral costs they think others face as exemplified by their institutional trust.

Author contributions

J.U.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; E.D.: investigation, data curation, writing - review and editing. This research was funded by Czech Science Foundation (#23-07257S).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Cliff McLenehan for his language support. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to [email protected]

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Table 1. Model of policy support (mixed linear regression model, DVs = policy support indices).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jan Urban

Jan Urban is a researcher at the Environment Center of the Charles University in Prague and an assistant professor at the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University. His research focuses on environmental attitude and behavior, and their change.

Ewa Duda

Ewa Duda is a research assistant at Global Change Research Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences and a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University. Her research focuses on the role of emotions in pro-environmental behavior and decision-making, and on the affective dimension of environmental attitudes within the Campbell paradigm.

Notes

1 While scholars differentiate between generalized trust (a relatively stable personality trait that manifests as a person’s propensity to trust) and particularized trust (trust towards specific entities; Schilke et al., Citation2021), we leave this distinction aside as we are interested in the functional role of trust in behavior rather than its origins.

2 Nonetheless, most scales within the paradigm infer attitude from cognitive and behavioral reactions (e.g., Brügger et al., Citation2019; Kaiser et al., Citation2018; Urban et al., Citation2021).

3 The questionnaire, data, and analytical R script can be found at https://osf.io/h6qva/

References

- Acedo-Carmona, C., and A. Gomila. 2014. “Personal Trust Increases Cooperation beyond General Trust.” PLoS One 9(8): E105559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105559.

- Ajzen, I. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Al Mamun, A., N. Hayat, M. Mohiuddin, A. A. Salameh, M. H. Ali, and N. R. Zainol. 2022. “Modelling the Significance of Value-Belief-Norm Theory in Predicting Workplace Energy Conservation Behaviour.” Frontiers in Energy Research 10:940595. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2022.940595.

- Allport, G. W. 1935. Attitudes. In Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by C. Murchison. Worcester, MA: Clark University Press.

- Anderson, B., T. Böhmelt, and H. Ward. 2017. “Public Opinion and Environmental Policy Output: A Cross-National Analysis of Energy Policies in Europe.” Environmental Research Letters 12(11):114011. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa8f80.

- Andrich, D., and I. Marais. 2019. A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory: Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-7496-8.

- Bamberg, S., and G. Möser. 2007. “Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviour.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 27(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002.

- Batool, N., M. D. Wani, S. A. Shah, and Z. A. Dada. 2023. “Theory of Planned Behavior and Value-Belief Norm Theory as Antecedents of Pro-Environmental Behaviour: Evidence from the Local Community.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 34:1–17. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2023.2205912.

- Bauer, P. C., F. Keusch, and F. Kreuter. 2019. “Trust and Cooperative Behavior: Evidence from the Realm of Data-Sharing.” PLOS One. 14(8):e0220115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220115.

- Bauske, E., A. Kibbe, and F. G. Kaiser. 2022. Opinion Polls as Measures of People’s Personal Commitment to a Goal: Environmental Attitude in Germany From 1996 to 2018. Manuscript in Preparation.

- Bellemare, C., and S. Kröger. 2007. “On Representative Social Capital.” European Economic Review 51(1):183–202. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2006.03.006.

- Bockarjova, M., and L. Steg. 2014. “Can Protection Motivation Theory Predict Pro-Environmental Behavior? Explaining the Adoption of Electric Vehicles in The Netherlands.” Global Environmental Change 28:276–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.010.

- Bond, T. G., and C. M. Fox. 2012. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Braun Kohlová, M., and J. Urban. 2020. “Buy Green, Gain Prestige and Social Status.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 69:101416. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101416.

- Brügger, A., M. H. Dorn, C. Messner, and F. G. Kaiser. 2019. “Conformity Within the Campbell Paradigm: Proposing a New Measurement Instrument.” Social Psychology 50:133–44. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000366.

- Bunduchi, R. 2008. “Trust, Power and Transaction Costs in B2B Exchanges—A Socio-Economic Approach.” Industrial Marketing Management 37(5):610–22. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.05.003.

- Byrka, K., and F. G. Kaiser. 2013. “Health Performance of Individuals within the Campbell Paradigm.” International Journal of Psychology 48(5):986–99. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.702215.

- Castellini, G., M. Acampora, L. Provenzi, L. Cagliero, L. Lucini, and S. Barello. 2023. “Health Consciousness and Pro-Environmental Behaviors in an Italian Representative Sample: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Scientific Reports 13(1):8846. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35969-w.

- Cologna, V., and M. Siegrist. 2020. “The Role of Trust for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 69:101428. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101428.

- Davidovic, D., and N. Harring. 2020. “Exploring the Cross-National Variation in Public Support for Climate Policies in Europe: The Role of Quality of Government and Trust.” Energy Research & Social Science 70:101785. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101785.

- de Boeck, P., and M. Wilson. 2011. Explanatory Item Response Models: A Generalized Linear and Nonlinear Approach. New York, NY: Springer.

- Dietz, T., A. Dan, and R. Shwom. 2007. “Support for Climate Change Policy: Social Psychological and Social Structural Influences.” Rural Sociology 72(2):185–214. doi: 10.1526/003601107781170026.

- Dincecco, M. 2017. State Capacity and Economic Development: Present and Past. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108539913.

- Douenne, T., and A. Fabre. 2022. “Yellow Vests, Pessimistic Beliefs, and Carbon Tax Aversion.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 14(1):81–110. doi: 10.1257/pol.20200092.

- Dunlap, R. E. 2008. “The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: From Marginality to Worldwide Use.” The Journal of Environmental Education 40(1):3–18. doi: 10.3200/JOEE.40.1.3-18.

- Dunlap, R. E., and K. D. Van Liere. 1978. “The “New Environmental Paradigm”: A Proposed Measuring Instrument and Preliminary Results.” Journal of Environmental Education 9:10–9. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1978.10801875.

- Dyer, J. H., and W. Chu. 2003. “The Role of Trustworthiness in Reducing Transaction Costs and Improving Performance: Empirical Evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea.” Organization Science 14(1):57–68. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.1.57.12806.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. Chaiken. 1993. The Psychology of Attitudes. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, & Janovich.

- Fairbrother, M. 2016. “Trust and Public Support for Environmental Protection in Diverse National Contexts.” Sociological Science 3:359–82. doi: 10.15195/v3.a17.

- Fairbrother, M., I. Johansson Sevä, and J. Kulin. 2019. “Political Trust and the Relationship between Climate Change Beliefs and Support for Fossil Fuel Taxes: Evidence from a Survey of 23 European Countries.” Global Environmental Change 59:102003. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102003.

- Faure, C., M.-C. Guetlein, J. Schleich, G. Tu, L. Whitmarsh, and C. Whittle. 2022. “Household Acceptability of Energy Efficiency Policies in the European Union: Policy Characteristics Trade-Offs and the Role of Trust in Government and Environmental Identity.” Ecological Economics 192:107267. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107267.

- Franzen, A., and R. Meyer. 2010. “Environmental Attitudes in Cross-National Perspective: A Multilevel Analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000.” European Sociological Review 26(2):219–34. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp018.

- Franzen, A., and D. Vogl. 2013. “Two Decades of Measuring Environmental Attitudes: A Comparative Analysis of 33 Countries.” Global Environmental Change 23(5):1001–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.009.

- Gächter, S., B. Herrmann, and C. Thöni. 2004. “Trust, Voluntary Cooperation, and Socio-Economic Background: Survey and Experimental Evidence.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 55(4):505–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2003.11.006.

- Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gerdes, R., E. Bauske, and F. G. Kaiser. 2023. “A General Explanation for Environmental Policy Support: An Example Using Carbon Taxation Approval in Germany.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 90:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102066.

- Glaeser, E. L., D. I. Laibson, J. A. Scheinkman, and C. L. Soutter. 2000. “Measuring Trust.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3):811–46. doi: 10.1162/003355300554926.

- Hammar, H., and S. C. Jagers. 2006. “Can Trust in Politicians Explain Individuals’ Support for Climate Policy? The Case of CO2 Tax.” Climate Policy 5:6. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2006.9685582.

- Hampton, S., and L. Whitmarsh. 2023. “Choices for Climate Action: A Review of the Multiple Roles Individuals Play.” One Earth 6(9):1157–72. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2023.08.006.

- ISSP Research Group 2023. International Social Survey Programme: Environment IV - ISSP 2020 (2.0.0) [Dataset]. Mannheim, Germany: GESIS, Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. doi: 10.4232/1.14153.

- Kaiser, F. G., and A. Biel. 2000. “Assessing General Ecological Behavior: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between Switzerland and Sweden.” European Journal of Psychological Assessment 16(1):44–52. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.16.1.44.

- Kaiser, F. G., K. Byrka, and T. Hartig. 2010. “Reviving Campbell’s Paradigm for Attitude Research.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14(4):351–67. doi: 10.1177/1088868310366452.

- Kaiser, F. G., M. Merten, and E. Wetzel. 2018. “How Do We Know We Are Measuring Environmental Attitude? Specific Objectivity as the Formal Validation Criterion for Measures of Latent Attributes.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 55, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.01.003.

- Kaiser, F. G., R. Gerdes, and F. König. 2023. “Supporting and Expressing Support for Environmental Policies.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 87:101997. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101997.

- Kaiser, F. G., G. Hübner, and F. X. Bogner. 2005. “Contrasting the Theory of Planned Behavior With the Value-Belief-Norm Model in Explaining Conservation.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35(10):2150–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02213.x.

- Kaiser, F. G., and C. Keller. 2001. “Disclosing Situational Constraints to Ecological Behavior: A Confirmatory Application of the Mixed Rasch Model.” European Journal of Psychological Assessment 17(3):212–21. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.17.3.212.

- Kaiser, F. G., A. Kibbe, and L. Hentschke. 2021. “Offsetting Behavioral Costs with Personal Attitudes: A Slightly More Complex View of the Attitude-Behavior Relation.” Personality and Individual Differences 183:111158. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111158.

- Kaiser, F. G., and F. Lange. 2021. “Offsetting Behavioral Costs with Personal Attitude: Identifying the Psychological Essence of an Environmental Attitude Measure.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 75:101619. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101619.

- Kaiser, F. G., and M. Wilson. 2019. “The Campbell Paradigm as a Behavior-Predictive Reinterpretation of the Classical Tripartite Model of Attitudes.” European Psychologist 24(4):359–74. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000364.

- Kim, S. C., and S. L. Cooke. 2021. “Using the Health Belief Model to Explore the Impact of Environmental Empathy on Behavioral Intentions to Protect Ocean Health.” Environment and Behavior 53(8):811–36. doi: 10.1177/0013916520932637.

- Klöckner, C. A. 2013. “A Comprehensive Model of the Psychology of Environmental Behaviour—A Meta-Analysis.” Global Environmental Change 23(5):1028–38. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.014.

- Kock, F., A. Berbekova, and A. G. Assaf. 2021. “Understanding and Managing the Threat of Common Method Bias: Detection, Prevention and Control.” Tourism Management 86:104330. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330.

- Kukowski, C. A., W. Hofmann, J. Roozenbeek, S. van der Linden, M. P. Vandenbergh, and K. S. Nielsen. 2023. “The Perceived Feasibility of Behavior Change is Positively Associated with Support for Domain-Matched Climate Policies.” One Earth 6(11):11. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2023.10.017.

- Lange, F. 2022. “Behavioral Paradigms for Studying Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Systematic Review.” Behavior Research Methods 55(2):600–22. doi: 10.3758/s13428-022-01825-4.

- Liebe, U. 2010. “Different Routes to Explain Pro-Environmental Behavior: An Overview and Assessment.” Analyse & Kritik 32(1):137–57. doi: 10.1515/auk-2010-0108.

- Maloney, M. P., and M. P. Ward. 1973. “Ecology: Let’s Hear from the People. An Objective Scale for Measurment of Ecological Attitudes and Knowledge.” American Psychologist 28:583–6. doi: 10.1037/h0034936.

- Mayerl, J., and H. Best. 2018. “Two Worlds of Environmentalism?” Nature and Culture 13(2):208–31. doi: 10.3167/nc.2018.130202.

- Mayerl, J., and H. Best. 2019. “Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions to Protect the Environment: How Consistent is the Structure of Environmental Concern in Cross-National Comparison?” International Journal of Sociology 49(1):27–52. doi: 10.1080/00207659.2018.1560980.

- McGrath, L. F., and T. Bernauer. 2017. “How Strong is Public Support for Unilateral Climate Policy and What Drives It?” WIREs Climate Change 8(6):e484. doi: 10.1002/wcc.484.

- OECD. 2017. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust. Paris, France: OECD. doi: 10.1787/9789264278219-en.

- Ostrom, E. 2009. “A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems.” Science 325(5939):419–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1172133.

- Patterson, J. J. 2023. “Backlash to Climate Policy.” Global Environmental Politics 23(1):68–90. doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00684.

- Pestello, F. G. 2007. Attitudes and Behavior. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, 1st ed., edited by G. Ritzer. New York, NY: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa071.

- Pitt, M. A., and I. J. Myung. 2002. “When a Good Fit Can Be Bad.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6(10):421–5. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01964-2.

- Poteete, A. R., M. A. Janssen, and E. Ostrom. 2010. Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Rainear, A. M., and J. L. Christensen. 2017. “Protection Motivation Theory as an Explanatory Framework for Proenvironmental Behavioral Intentions.” Communication Research Reports 34(3):239–48. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2017.1286472.

- Rhodes, E., J. Axsen, and M. Jaccard. 2017. “Exploring Citizen Support for Different Types of Climate Policy.” Ecological Economics 137:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.02.027.

- Rosenberg, M. J., and C. I. Hovland. 1960. Cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of attitudes. Pp. 1–14, in Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency among Attitude Components, edited by C. I. Hovland & M. J. Rosenberg. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Rothstein, B. 2005. Social Traps and the Problem of Trust. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511490323.

- Savari, M., H. E. Damaneh, H. E. Damaneh, and M. Cotton. 2023. “Integrating the Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behaviour to Investigate Farmer Pro-Environmental Behavioural Intention.” Scientific Reports 13(1):5584. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32831-x.

- Schilke, O., M. Reimann, and K. S. Cook. 2021. “Trust in Social Relations.” Annual Review of Sociology 47(1):239–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-082120-082850.

- Shafiei, A., and H. Maleksaeidi. 2020. “Pro-Environmental Behavior of University Students: Application of Protection Motivation Theory.” Global Ecology and Conservation 22:e00908. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00908.

- Silver, N. 2013. The Signal and the Noise: The Art and Science of Prediction. London, UK: Penguin Books.

- Simon, H. A. 1955. “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 69(1):99. doi: 10.2307/1884852.

- Smith, C. L., and D. J. Brooks. 2013. Security Risk Management. Pp. 51–80, in Security Science. Oxford, UK: Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394436-8.00003-5.

- Spadaro, G., K. Gangl, J.-W. Van Prooijen, P. A. M. Van Lange, and C. O. Mosso. 2020. “Enhancing Feelings of Security: How Institutional Trust Promotes Interpersonal Trust.” Plos ONE 15(9):e0237934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237934.

- Stern, P. C. 2000. “Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior.” Journal of Social Issues 56(3):407–24. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00175.

- Stern, P. C., T. Dietz, T. Abel, G. A. Guagnano, and L. Kalof. 1999. “A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism.” Human Ecology Review 6(2):81–97.

- Telesiene, A., and M. Hadler. 2023. “Dynamics and Landscape of Academic Discourse on Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors since the 1970s.” Frontiers in Sociology 8:1136972. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.1136972.

- Tian, H., and X. Liu. 2022. “Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(11):6721. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116721.

- Tjernström, E., and T. Tietenberg. 2008. “Do Differences in Attitudes Explain Differences in National Climate Change Policies?” Ecological Economics 65(2):315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.06.019.

- Tyler, T. R. 2006. Why People Obey the Law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Urban, J. 2016. “Are we Measuring Concern about Global Climate Change Correctly? Testing a Novel Measurement Approach with the Data from 28 Countries.” Climatic Change 139(10):397–411. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1812-0.

- Urban, J., Š. Bahník, and M. Braun Kohlová. 2023. “Pro-Environmental Behavior Triggers Moral Inference, Not Licensing by Observers.” Environment and Behavior 55(1–2):74–98. doi: 10.1177/00139165231163547.

- Urban, J., and M. Braun Kohlová. 2020. “The COVID-19 Crisis Diminishes Neither Pro-Evnvironmental Motivation nor Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Panel Study [Preprint].” PsyArXiv doi: 10.31234/osf.io/k2gnm.

- Urban, J., and F. G. Kaiser. 2022. “Environmental Attitudes in 28 European Countries Derived from Atheoretically Compiled Opinions and Self-Reports of Behavior.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:875419. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875419.

- Urban, J., D. Vačkářová, and T. Badura. 2021. “Climate Adaptation and Climate Mitigation Do Not Undermine Each Other: A Cross-Cultural Test in Four Countries.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 77:101658. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101658.

- van der Werff, E., L. Steg, and K. Keizer. 2014. “Follow the Signal: When past Pro-Environmental Actions Signal Who You Are.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 40:273–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.07.004.

- Verhallen, T. M. M., and R. G. M. Pieters. 1984. “Attitude Theory and Behavioral Costs.” Journal of Economic Psychology 5(3):223–49. doi: 10.1016/0167-4870(84)90024-2.

- Wang, F., J. Gu, J. Wu, and Y. Wang. 2024. “Perspective Taking and Public Acceptance of Nuclear Energy: Mediation of Trust in Government and Moderation of Cultural Values.” Journal of Cleaner Production 434:140012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140012.

- Wang, Y., J. Liang, J. Yang, X. Ma, X. Li, J. Wu, G. Yang, G. Ren, and Y. Feng. 2019. “Analysis of the Environmental Behavior of Farmers for Non-Point Source Pollution Control and Management: An Integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Protection Motivation Theory.” Journal of Environmental Management 237:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.070.

- Wiseman, J., T. Edwards, and K. Luckins. 2013. “Post Carbon Pathways: A Meta-Analysis of 18 Large-Scale Post Carbon Economy Transition Strategies.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 8:76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2013.04.001.

- Wright, B. D., and J. M. Linacre. 1994. “Reasonable Mean-Square Fit Values.” Rasch Measurement Transactions 8:370–1.

- Yuriev, A., M. Dahmen, P. Paillé, O. Boiral, and L. Guillaumie. 2020. “Pro-Environmental Behaviors through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Scoping Review.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 155:104660. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104660.

- Zhang, H., L. Zhou, N. Liu, and L. Zhang. 2022. “Seemingly Bounded Knowledge, Trust, and Public Acceptance: How Does Citizen’s Environmental Knowledge Affect Facility Siting?” Journal of Environmental Management 320:115941. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115941.

Appendix A

Figure A5. Model-predicted country-specific policy support as a function of environmental attitude (mixed linear regression model).

Figure A6. Model-predicted country-specific policy support as a function of institutional trust (mixed linear regression model).

Figure A14. Average levels of institutional trust in groups of people choosing different policies to make businesses protect the environment (means and their 95% CIs).

Figure A15. Average levels of institutional trust in groups of people choosing different policies to make individuals protect the environment (means and their 95% CIs).

Table A1. Country-level descriptive statistics.

Table A2. Binary coding of items used to construct the measure of environmental attitude.

Table A3. Support for policy measures across countries (means and standard deviations of the support score).

Table A4. Model-predicted country-specific regression slopes (mixed linear regression model).

Table A5. Country-specific models of policy support (linear regression).

Table A6. Choice of optimal policy to make businesses protect the environment (percentage).

Table A7. Test of equality of trust scores across groups choosing different measures to make businesses protect the environment (ANOVA with polynomial contrasts).

Table A8. Test of the linear trend across groups choosing different measures to make businesses protect the environment (ANOVA with linear trend partition).

Table A9. Choice of optimal policy to make businesses protect the environment (percentage).

Table A10. Test of equality of trust scores across groups choosing different measures to make individuals protect the environment (ANOVA with polynomial contrasts).

Table A11. Test of the linear trend across groups choosing different measures to make individuals protect the environment (ANOVA with linear trend partition).

Table A12. Sensitivity analysis of policy support (mixed linear regression model, DVs = policy support indices).