Abstract

Research has long claimed that women engage less than men in environmental political participation (EPP) (protests, petitions), despite having higher levels of environmental concern and vulnerability. Using the ISSP’s 2020 Environment Module including 28 countries, we argue that higher gender equality and socio-economic development can allow women to voice environmental grievances. Using multi-level models, we examine the effects of gender equality on gender differences in protests, petitions, and boycotts. Offering a more encompassing approach, we distinguish individual from collective, and non-confrontational from confrontational engagement forms. We find that women actually participate more than men, but mainly in individual and non-confrontational EPP forms (petitions, boycotts), and with substantial cross-country variation. Moreover, considering women’s historical barriers from participating in politics, we argue that structural gender inequality remains an important limitation to women’s engagement. Cross-level interactions indicate that especially when in more egalitarian countries, women take the lead in several types of EPP.

Introduction

Environmental challenges are perceived and experienced unequally across and within countries. Being a woman or having low socio-economic status increases vulnerability, and current disparities in social and physical vulnerability to, e.g. rising temperatures, pollution, or extreme weather events are expected only to grow as climate change escalates (Birkmann et al. Citation2022; Sultana Citation2013; Zhou et al. Citation2022). Consequently, environmental political activism all around the world has increased (Ares and Bolton Citation2020). Since environmental vulnerability reflects preexisting inequality, such as belonging to a marginalized group (Birkmann et al. Citation2022; Shayegh and Dasgupta Citation2022), social inequalities hold a key role in how people are affected by, perceive, and politically respond to environmental challenges. One important dimension of this is gender: There are known significant gender differences, for instance, in the felt effects of climate change, and also in responses to its negative consequences (UNWomen Citation2022). Gendered environmental grievances and inequalities manifest in women’s disproportionate loss of opportunities, decreased personal health and wellbeing, and increases in gender-based discrimination and violence (Eastin Citation2018; UNFCCC Citation2022). However, how these grievances and inequalities translate into gendered patterns of environmental political mobilization is less understood.

Women across countries are both more affected by Awiti (Citation2022; Eastin Citation2018), and concerned about environmental issues than men (Knight Citation2019; Li et al. Citation2019; McCright and Xiao Citation2014), but this gender disparity is for some reason not reflected in women’s political environmental activism. Instead, several studies report that that women engage significantly less in than men do in environmental political activism (Tindall et al. Citation2003; Yang and Wilson Citation2023), while others find no gender differences across countries (Balzekiene and Telesiene Citation2012; Briscoe et al. Citation2019; El Khoury et al. Citation2022; Hunter et al. Citation2004; Schumacher Citation2014; Trelohan Citation2021).

This is puzzling for a number of reasons. Women consistently dominate nonpolitical and household-related environmental behaviors across many countries, such as recycling or reducing electricity (Balzekiene and Telesiene Citation2012; Dzialo Citation2017; Kennedy and Kmec Citation2018). Moreover, women and girls have notably spearheaded environmental fights in recent years; ranging from global Fridays for Future school strikes for climate (Chiu Citation2019) to taking on leading roles in green politics and legal action (Workman et al. Citation2022), and prioritizing environmental issues more than men when on corporate boards (Strumskyte et al. Citation2022). Women working in the European Parliament are more likely to support environmentally friendly acts than their male counterparts, even when reporting similar levels of environmental concern (Ramstetter and Habersack Citation2019). Yet, while women may act more environmentally at home and when in positions of influence, they are still very underrepresented in environmental politics in general (Ramstetter and Habersack Citation2019; Strumskyte et al. Citation2022). These patterns, however, vary widely across countries.

In this study, we revisit the gender gap in environmental political behavior, focusing on three main contributions. First, we conceptualize and measure environmental political participation in a more nuanced way. By distinguishing conceptually between individual versus collective, and confrontational versus non-confrontational types of participation, we attempt to theorize and empirically show why some types of participation are more likely to occur among women. Secondly, we argue that women’s environmental political participation in part depends on gendered political opportunity structures, which differ across countries. More specifically, higher gender equality in society, reflected in, e.g. higher female political representation and labor market participation, allows women to voice their environmental grievances more in certain countries, even outperforming men’s participation. Finally, using the 2020 International Social Survey Program (ISSP) data IV module on environmental attitudes and behaviors, we empirically analyze under which conditions and for which types of behaviors we find gender differences in environmental political participation. We ask, 1. Are there consistent gender differences across different forms of environmental political participation? and 2. Does a country’s level of gender equality matter more for women’s environmental political participation than for men’s?

After a theory and literature review, we present 3 hypotheses which help answer these two questions. We analyze the ISSP data environmental module using multi-level mixed effects logistic regression models on a sample of 44,100 respondents in 28 countries around the world. Our analyses show that the type of environmental political behavior matter for women’s participation. Interestingly, using the most recent 2020 data, women outperform men in individual and non-confrontational types of participation (boycotts and petitions), and are on par with men in confrontational types of behavior. Cross-level interactions with random slopes show that gendered political opportunity structures provide a fertile ground for female engagement. In the next section, we present the theoretical argument and give an overview over the existing literature. Thereafter we introduce our empirical approach, present our results, and conclude with a discussion of the findings and their limitations.

Theoretical background & literature review

Environmental political participation (EPP)

Political participation can be defined as voluntary activity or action by people in their role as citizens (rather than, e.g. government employees), which specifically concerns government, politics, or the state, in a broad sense (Deth Citation2016:1). Thus, it includes activities like “[…] voting, demonstrating, donating money, contacting a public official, and boycotting [or] buying fairtrade products”, and excludes things like being interested in politics or watching television (Deth Citation2016:1). Here, we focus on one issue area, the environment, and hence environmental political participation (EPP). This issue-specific focus narrows the above definition down to its pro-environmental activities, making EPP political participation which specifically aims to influence environmental governance or politics (Levy and Zint Citation2013). It includes activist and political activities such as attending environmental protests, signing petitions for environmental causes, voting for a green party, and environmental political consumption. It excludes behaviors like recycling, reducing water, vegetarianism, and other nonpolitical activities which may still serve pro-environmental purposes. For EPP, we find no reports of women engaging more on average than men across countries, despite women’s higher levels of environmental concern and grievances.

Between different forms of EPP, there is relatively little overlap (those who protest may not boycott), as engagement in each form can be influenced by different factors (Steenvoorden Citation2018). Firstly, EPP can be grouped into more individual or collective forms of engagement. An example of an individual form of action is political consumption (e.g. boycotting), where a consumer can use their main economic activity and area of influence – their purchasing power – to voice their political, ethical, and environmental interests by avoiding a product, producing a cost for the actor they wish to influence (Koos Citation2012). Such activities do not require organized collective action, but to be effective, many people must act in a similar way. Each person, with their own motivation, can therefore separately engage in this form of participation, together (Deth Citation2016). More collective EPP forms, such as demonstrations, tend to be organized on a larger scale, and rely on the impact of the participants’ organized collective action and shared opinion (Tschakert et al. Citation2023).

The distinction between individual and collective forms of participation becomes particularly relevant when discussing gendered patterns of engagement. Individual EPP such as political consumption sticks out as favored by women in prior literature, and is one of the few forms of political participation where women appear to consistently engage more than men (Dzialo Citation2017; Gundelach and Kalte Citation2021; Koos Citation2012). Many studies categorize women’s prowess in environmental political consumption together with nonpolitical environmental behaviors, however (El Khoury et al. Citation2022; Hunter et al. Citation2004; Kennedy and Kmec Citation2018). These often do so referring to the concept of environmental behaviors in the “private” as opposed to the “public” sphere, roughly indicating the social space inside or outside the home, a traditionally female domain, as well as a behavioral focus in which private actions have direct effects (e.g. conservation) and public ones have indirect effects (e.g. influencing policy) (Stern Citation2000). But, categorizing EPP forms like environmental boycotting together with nonpolitical actions, like recycling, lumps activities which aim to have influence over environmental politics and governance, with those which are simply environmentally friendly. This difference of which category political consumption is placed in may contribute to the finding that women engage less than men in EPP. We argue that, in line with van Deth’s conceptualization, it is a form of political participation, though different from more collective and confrontational actions like protesting.

Collective action such as protesting are typically male-dominated across countries (Coffé and Bolzendahl Citation2010; Dodson Citation2015), with the occasional rare exception (German climate protests) (Noth and Tonzer Citation2022). However, there are indications that collective but non-confrontational forms, like petitioning, may be more attractive to women (Dodson Citation2015; Marien et al. Citation2010), implying that there is important nuance between actions. Beyond the individual-collective spectrum, types of political participation also differ in the extent to which they are confrontational or not. By confrontational, we refer to disruptive action; common examples include demonstrations, strikes, and sit-ins. These aim to impose costs through challenging authorities, jeopardizing careers, or economic losses. Non-confrontational actions employ more conventional tactics, such as petitions, lawsuits, or boycotts. These less disruptive forms often enjoy greater institutional and legal protection, and signal a more broad-based movement support to their target (Dodson Citation2015:378). Women have been found to be more willing to participate in non-confrontational forms, whereas men are drawn to confrontational forms (Dodson Citation2015). Making these distinctions can thus offer more nuance when examining participation patterns.

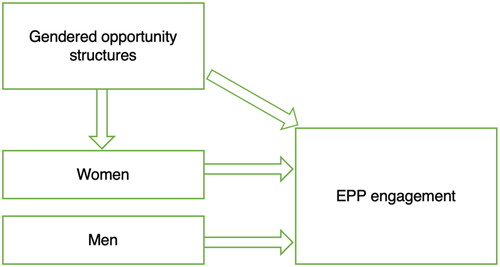

A typology of EPP ranging from individual and non-confrontational behavior to collective and confrontational behavior has been produced (). An individual and non-confrontational form of EPP is environmental boycotting. As a “middle ground” on the scale, environmental petitioning does not require confrontation with others, but the purpose of which is to gather enough signatures to collectively make a political impact by revealing a list of supporters making a formal request to an influential actor (Polyas Citation2023). This is therefore a collective but non-confrontational form of EPP. Lastly, the most collective and confrontational form of action on the scale is environmental protesting, in the sense of a demonstration, where support for an environmental cause is shown by participants expressing their shared concerns in a public space.

Explaining gender differences in EPP

Gender, as opposed to sex, is a social construct. Whereas sex is an assigned label given at birth based on one’s physical body, gender is a result of personal and psychological characteristics given and taught to men and women within a given culture (Hoominfar Citation2019). Gender socialization theory thus describes how people learn to “do” gender from a very young age, i.e. the internalization of gender norms as they interact with key socialization agents such as family and other formative social institutions (Hoominfar Citation2019). Sex and gender naturally largely overlap, with important minority exceptions (such as trans or non-binary people)Footnote1. Applied to environmental attitudes and behavior, this approach argues that women are socialized and expected to take on roles as caregivers toward people and nature. This encourages and leads women to develop more of traits like empathy and altruism, and ultimately being more pro-environmental (Briscoe et al. Citation2019). At the same time, this process teaches women to be more politically passive, rule-abiding, and compassionate, while men are encouraged to take on public and powerful roles, autonomy, and leadership (Coffé and Bolzendahl Citation2010). This theoretical approach thus explains why women would be more concerned and caring for the environment, yet less likely than men to exercise such attitudes by engaging in collective and confrontational EPP. Classic variables used to capture the presence and influence of gender socialization on environmental behavior hence include “feminized” traits like concern for others and for the environment, altruism, and ethical values (Dietz et al. Citation2002; McCright and Xiao Citation2014; Zelezny et al. Citation2000).

Socialization theory has been used to highlight that women engage more in nonpolitical and household-based environmentalism, such as recycling, but less in environmental political, confrontational, and collective action, as befits their socialization as home-makers and care-givers (Briscoe et al. Citation2019; Hunter et al. Citation2004). In line with this, studies of how personal conflict orientation affects political behavior show that women are more likely to dislike confrontation and conflict than men, though this does not necessarily deter them from engaging with politics. More importantly, “Men find arguments more enjoyable than women do, contributing to gender gaps in attention to politics, enjoyment of political discussion, and political action” (Wolak Citation2020:135). They refer to the gender socialization of men, to engage in and enjoy assertiveness, aggression, and argumentation as more compatible with the contentious nature of politics, and collective action in particular. The socialization of girls and women, on the other hand, encourages them to value compromise and maintain good social relationships, making them more likely to avoid more contentious political engagement, since it could impose unwanted costs (Wolak Citation2020). As predicted by gender socialization theory, these gendered engagement patterns begin to form already in childhood. When studying the political engagement intentions of 14-year-olds, boys envision engaging in radical and confrontational actions such as street blockades and occupations, or joining political parties, while girls report significantly higher levels of wishing to volunteer, collect money or petition signatures, voting, and other more individual and non-confrontational activities (Hooghe and Stolle Citation2004). The authors emphasize the importance of distinguishing between different forms of political action in order to discern gendered engagement patterns, as well as the fact that girls actually report higher overall levels of intended engagement than boys when choosing from an option-range that also includes non-confrontational and less collective options (Hooghe and Stolle Citation2004). Corresponding to the first research question, we therefore posit that:

H1. Women will engage more than men in more individual and non-confrontational forms of EPP (boycotting, petitioning).

The role of gendered political opportunity structures

Although gender equality is generally on the rise, women continue to face structural, socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural barriers to the historically male-dominated political and public sphere (Masad Citation2020). This is fueled by discriminatory laws, practices, gender stereotypes, lack of access to education and health care, and disproportionate effects of poverty on women (UNWomen Citation2023). While there is great country variation in the extent of these challenges, no country has yet achieved gender equality. International expert reports state that it would take 132 years until gender equality is achieved at the current rate of developments (World Economic Forum Citation2022). In 2022, the EU’s Gender Equality Index score was 68.6 out of 100 (EIGE Citation2022), in which equal decision-making, influence, and political participation ranked the lowest. That these challenges should affect gender differences in participation was noted by Paul Mohai already in 1992: “The factors that limit the general political activity of women in all likelihood similarly affect environmental activity” (1992, p. 6). Many structural “limiting factors” that women faced in 1992 remain relevant, yet, their effects on women’s EPP across countries are largely unexplored.

Our argument is that women’s EPP is built on (a) motivation and (b) ability to act on that motivation, which is in part dependent on the (c) gendered opportunity structures of one’s country-context. When afforded greater opportunities, women have been known to express dissatisfaction with traditional confining behaviors or norms, seek new social roles, and increase their political and labor force participation over time (National Intelligence Council Citation2021). In peace and conflict literature, structural gender inequality has contributed to women’s inability to participate in protests: In-depth case studies show that where equal or higher levels of political discontent were reported by women, men still protested more, which was explained to be a result of preexisting gender inequality and discrimination leading to fewer mobilization norms, options, and resources for women (Schaftenaar Citation2022:32). In more gender equal country-contexts, women have been found to be more likely to participate in confrontational collective action (Dodson Citation2015). In other words, when gender equality increases, the political culture and system can enable an increased ability to engage, particularly for women, matching their level of willingness, and resulting in their increased participation (). Other widely used social movement theories, such as those focusing on grievances or resources as the main driver behind mobilization, contribute importantly to how we understand the developments of activist behaviors. However, integrated into the political opportunity structure approach, it is the presence or absence of political opportunities that enable these things to lead to collective action (Koopmans Citation1999; Snow and Soule Citation2010).

Political opportunity structures have been defined as “consistent but not necessarily formal, permanent, or national signals to social or political actors which either encourage or discourage them to use their internal resources to form social movements” (Tarrow Citation1996:54, Emphasis in original). Four dimensions of this are often highlighted, as summarized by McAdam; (1) the relative openness or closure of the institutionalized political system; (2) the stability or instability of that broad set of elite alignments that typically undergird a polity; (3) the presence or absence of elite allies; and (4) the state’s capacity and propensity for repression (McAdam Citation1996:27). On the one hand, critics of this approach state that it risks becoming an explanation “sponge”, soaking up everything from culture and crises to policy shifts in attempts to explain collective action. This critique originates from the wide variety of variables that have been used to supposedly represent political opportunity structures (Giugni Citation2011). On the other hand, the strength of the approach lies in its cross-country comparisons, where it can be used flexibly to identify macro-level patterns, changes, and inform us how collective action develops across contexts (Koopmans Citation1999). This study departs from Koopmans’ as well as Snow & Soule’s understanding of opportunities; that variations in opportunity are the most important determinants of variations in both levels and forms of collective action behavior (Koopmans Citation1999). These variations are to a significant extent structurally shaped: A (gendered) opportunity can thus be better defined as “constraints, possibilities, and threats that originate outside the mobilizing group, but affect its chances of mobilizing and/or realizing its collective interests” (Koopmans Citation1999:96). Sources of opportunity variations thus include structural characteristics of political systems, the behavior of allies, adversaries, or the public, economic structures, or cultural narratives (Koopmans Citation1999). While this approach risks becoming “sponge”-like, it derives explanatory power from its inclusivity. Emphasis, however, is placed on defining the specific opportunities, inequalities, and behaviors of interest.

This study hence sees opportunities as the freedom for individuals and collectives to express their (environmental) grievances and pursue their political interests (Snow and Soule Citation2010). In this, it is essential to recognize that opportunities affect groups differently depending on existing inequalities (Snow and Soule Citation2010). In line with Koopmans’ logic, we can firstly assume that social movements (such as the pro-environmental one) have aims, and use certain forms of action to further them. Secondly, participants weigh the relative advantages and disadvantages of the engagement options open to them, expecting a positive or negative reaction from the political environment (Koopmans Citation1999). When structural gender equality progresses, gendered opportunities open up for women to politically engage (McCammon et al. Citation2001). In political contexts which do not encourage certain expressions of environmental grievances, women thus face a much higher cost of participation, hindering their engagement (Snow and Soule Citation2010).

McCammon and colleagues (Citation2001) used gendered opportunity structures to explain the emergence and success of the women’s suffrage movement in the US. With the view of “opportunities emerging from changing gender relations and altered views about gender” (McCammon et al. Citation2001:66), they describe a process where cultural norms had women’s sphere of influence clearly limited to their traditional domain, i.e. the household and child-rearing, effectively excluding them from any formal political power. As women begun to engage in what had long been male domains, such as education, paid employment, charity, and politics, the population – including the male political decision-makers – were persuaded over time to accept women’s wish and ability to participate in politics (McCammon et al. Citation2001:53). In other words, increased gender equality in terms of, e.g. employment and education ultimately contributed to women’s collective push for their right to political participation (McCammon et al. Citation2001). Corresponding to the second research question, we hence expect to find that:

H2a. Women in countries with higher levels of gender equality will engage more in EPP, compared to countries with lower levels of equality.

H2b. Women in countries with higher levels of gender equality will engage more in individual and non-confrontational EPP (boycotting, petitioning) in particular, compared to countries with lower levels of equality.

Data & methods

The data from the International Social Survey Program’s (ISSP) 2020 round was released in 2023, covering environmental attitudes, behaviors, and experiences (ISSP Citation2023). Due to the global Covid-19 pandemic, the year of survey data completion varies across countries; while the majority were surveyed in 2021, others were completed between 2019–2023. We merge this individual-level survey data with external macro-level data on gender equality as well as GDP per capita.

The full 2020 ISSP Environment module includes the following 28 countries: Australia (AU), Austria (AT), China (CH), Croatia (HR), Denmark (DK), Finland (FI), France (FR), Germany (DE), Hungary (HU), Iceland (IS), India (IN), Italy (IT), Japan (JP), Korea, Rep. (KR), Lithuania (LH), New Zealand (NZ), Norway (NO), the Philippines (PH), Russia (RU), Slovakia (SK), Slovenia (SI), South Africa (ZA), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), Switzerland (CH), Taiwan (TW), Thailand (TH), and the United States of America (US). With simple random sampling procedures, data collection varied by country, but consists of a number of questionnaire-based interview formats including face-to-face, via telephone, web-based, and more (Höllinger et al. Citation2020). Survey data was gathered from a total of 44,100 observations across five continents, with a notable focus on highly industrialized democracies (ISSP Citation2023). After adjusting for missing variables, 36,620 observations remain for analysisFootnote2.

Dependent variables

The study has three dependent variables with binary outcome values (), which represent the three behaviors on the scale of EPPFootnote3. These include environmental protest participation, petition signing, and boycotting. Due to the varying year of data collection, we cannot rule out that respondents in the small minority of countries surveyed late into or after the pandemicFootnote4 were not considering the pandemic time (when large public gatherings were discouraged/prohibited) as a partial reference point, which could lead to, e.g. under-reporting of protest behavior. However, this minority does not show lower levels of protest, meaning that we do not see this potential limitation reflected in specific biases in the data.

Table 1. Dependent variables.

Independent variables

The key independent variable in this study is gender, a binary variable. This measurement varies across countries: The majority asked respondents about their sex or gender, while some relied on national registers or interviewer observation (GESIS Citation2023). For this reason, we must consider the possibility of differences in respondents’ gender (assumed to reflect their gender socialization and experienced inequalities), and the male/female label recorded. This presents an unfortunate limitation to the study.

The distribution of all the independent variables is shown in . To capture several dimensions of gendered opportunity structures, we include one variable for economic and one for political gender equality. These are both externally sourced and lagged one year (2018).

Table 2. Independent variables.

The ratio of female to male labor force participation (LFP) is related to and determined by a range of factors related to women’s opportunities and rights. It has previously been used successfully to study the relationship between gender equality and women’s environmental behavior (Dzialo Citation2017). Female LFP is positively related to women’s improved health and freedom from violence, as well as education level, financial independence, and likelihood to have an influential job in areas like academia, business, and government (Winkler Citation2022). Countries with cultural norms of families having a male breadwinner and women’s place being in the home are more likely to have lower rates of female LFP (Winkler Citation2022). On an institutional level, factors that encourage and facilitate women’s LFP include labor market policies ensuring equal opportunities for women, and more gender equal child care policies such as parental leave (Winkler Citation2022). This economic gender equality variable was retrieved from the modeled International Labor Organization estimate, via the World Bank (World Bank Group Citation2023c).Footnote5

The political gender equality variable was retrieved from one of few datasets that includes all the participant countries of the 2020 ISSP (e.g. Taiwan). The University of Gothenburg’s V-Dem institute’s Women Political Empowerment index offers a comprehensive index capturing the extent to which women enjoy civil liberties (freedom of domestic movement, freedom from forced labor, property rights, access to justice), can participate in civil society (freedom of discussion, civil society organizations, representation among journalists), and are represented in politics (women in the legislature, political power distribution) (Dieleman and Andersson Citation2016).

Because opportunity variations for EPP also could arise from economic factors such as being a wealthy country (Koos Citation2012), we include (the logarithm of) GDP per capita. The high correlation of 0.7 (p < .001) between GDP and both economic and political gender equality indicates a positive and significant relationship (see Appendix A). While our focus lies on the effects of gender equality, comparing them to the effect of GDP in separate models can therefore be beneficial to discuss the influence of national wealth alone, for robustness reasons. This variable is measured in 2018 USD (World Bank Group Citation2023a). GDP per capita (henceforth GDP) is calculated as the gross domestic product of a country divided by the size of its population in the middle of a given year. It shows the sum of the gross value added by all resident producers in the economy, plus any product taxes not included in the valuation of output (World Bank Group Citation2023b).

Education level is an indicator of socio-economic status and is a well-known predictor of political participation (Marien et al. Citation2010). However, the strong relationship between education level and political participation can also be due to education’s relationship with political interest, and its subsequent relationship with participation (Marien et al. Citation2010). The survey measurement is divided into three levels; primary, secondary, and tertiary school. This mainly serves as a control for the predictive power of pursuing, and the ability to pursue, higher education. Age is also included as a control variable.

Environmental concern is included in many studies examining environmental attitudes and behaviors. The ISSP offers a general and open measurement of concern (see ). A potential downside of this approach is that nuance can be lost, as respondents may be more concerned about specific environmental issues. In this study, the relevance of environmental concern lies in its general influence on EPP – making such nuanced measures less important. Environmental ethics is measured by asking about doing what is right for the environment, despite personal costs. Particularly in combination with environmental concern, these variables capture important elements emphasized by gender socialization theory, where women are more likely to display altruism, care, and concern for other people and nature.

The environmental grievances index survey question asks about how affected the respondent’s neighborhood is, rather than their specific personal experience. While one’s neighborhood does include the respondent themselves, this may yield different results than if asked about being personally affected. Additionally, it is limited to the last 12 months, which the other psychological variables are not. Yet, being affected by extreme weather events, air pollution, or water pollution, are all potentially important factors motivating EPP, and as women are more vulnerable to environmental grievances like these, it is useful to include.

Methods

As is appropriate for mixed-effects models with binary outcome variables, we run multi-level mixed-effects logistic regression models using Stata 17. This allows for inclusion of the two relevant levels of analysis: Individuals and countries, i.e. testing the individual effects of gender on engagement in EPP, and if these are contingent on country-level gender equality. A strength of this method is that it accounts for that countries’ EPP engagement may have different starting points (random intercepts), allowing the regression parameters to vary (Davidovic et al. Citation2019). Additionally, to simplify interpretation, margins plots are used to illustrate select interactions.

For each dependent variable, six models are run. These models will, respectively, (1) estimate if there are gender differences, (2) control for age and education, (3) add the individual-level psychological variables, and then interact being female with (4) economic gender equality, (5) political gender equality, and (6) GDP. Heisig and Schaeffer (Citation2019) argue that one should always include a random slope for the lower-level variable (gender) when running cross-level interactions. Failing to do so risks severe anti-conservative statistical inference (Heisig and Schaeffer Citation2019). Recognizing that both the existence and magnitude of gendered effects of gender equality on EPP may vary between countries, we include a random slope for gender in all models.

Results & discussion

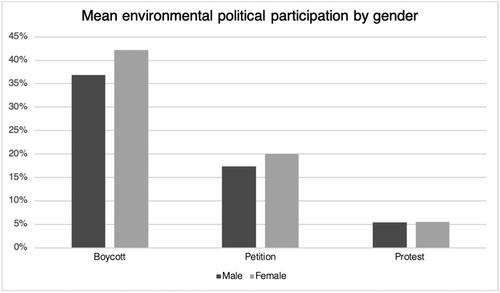

Initial descriptive data shows that as the EPP scale gets increasingly individual and non-confrontational, the rate of average participation also grows (). More than 40% of respondents engage in boycotting, while only 5% engage in protesting. Female-led gender differences are also noticeable for these more individual and non-confrontational behaviors, while differences appear non-existent for protesting.

Women do more

The first research question asks if there are consistent gender differences across different forms of EPP, building on literature that often finds women less politically engaged than men. However, in this sample we find that women do not engage less than men, but in fact consistently engage more in the majority of the included forms of EPP, on average. However, the existence and magnitude of these gender differences vary widely across countries. Supporting Hypothesis 1, show statistically significant positive relationships between being a woman and environmental petitioning and boycotting in particular (p < .001), as predicted by gender socialization theory. The gender effect is stronger for the most individual and non-confrontational form, boycotting, than for petitioning; the female lead thus diminishes as the EPP scale gets increasingly confrontational and collective in nature. For boycotting, probability of engagement increases by 7 percentage points if one is a woman, and by 3 percentage points for petitioning (see Supplemental Materials for AMEs tables). In the most collective and confrontational form of EPP, protesting, we find no statistically significant gender differences. While we did not expect women to outperform men, this importantly shows that women are on par with men in this historically male-dominated form of participation. One possible reason behind this could be that women’s higher levels of environmental grievances and concern motivates them to express and expand their mobilization tactics.

Table 3. Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression: Protest.

Table 4. Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression: Petition.

Table 5. Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression: Boycott.

For boycotting and petitioning, the effect of being female decreases when adding the psychological variables, which are all highly statistically significant (p < .001) across the forms of EPP. In line with our theoretical expectations that women are socialized to be more environmentally concerned, ethical, and altruistic, these variables account for part of the observed gender differences; but in line with prior research, they also cannot fully explain gender differences in EPP. The effect of environmental concern is the strongest for protesting, while it is overtaken by environmental ethics in the case of boycotting. In the case of environmental grievances, the effect is the strongest for protesting, and the weakest for boycotting. This indicates that such distinction between forms of EPP in future research can yield better insight into what motivates and influences different kinds of engagement.

Education level is, unsurprisingly, a significant predictor of boycotting and petitioning, the magnitude of which grows as education level gets higher. For protesting, this is not the case, again illustrating the importance of distinguishing between forms in this way. The effects of age are weak, though consistently statistically significant as well. However, while age has a negative relationship with protesting and petitioning, with boycotting it is positive. One interpretation of this is that older individuals may be more able or willing to consider boycotting as a means of environmental activism than other forms.

When do women take the lead?

Our second research question asks if a country’s level of gender equality matters more for women’s EPP than for men’s. In other words, does living in a more gender equal context encourage women to voice their environmental grievances more? We find significant variation both between the effect of political and economic gender equality as well as between the forms of EPP. illustrate interaction effects of being a woman when there is a one-unit change in the macro variable, holding all other variables constant.

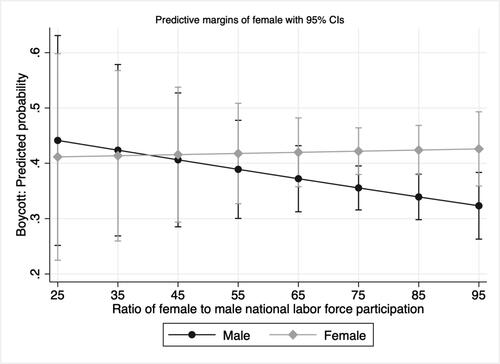

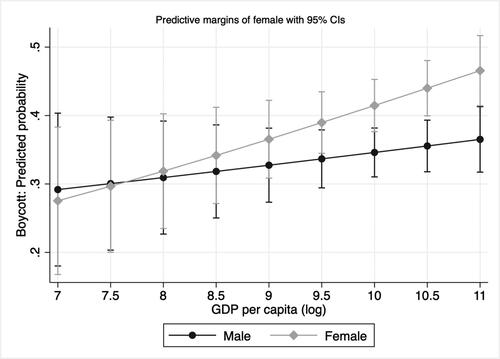

Figure 4. Predicted probability of Boycott: Interaction between gender and economic gender equality. Covariates include age and education level.

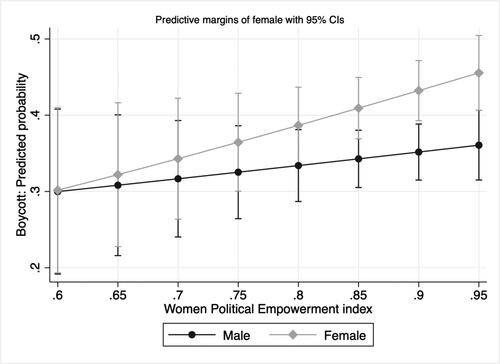

Figure 5. Predicted probability of Boycott: Interaction between gender and political gender equality. Covariates include age and education level

Figure 6. Predicted probability of Boycott: Interaction between gender and GDP. Covariates include age and education level.

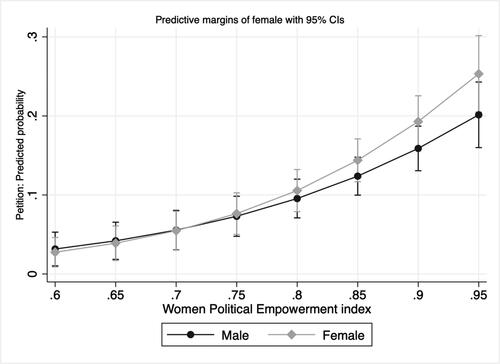

Figure 7. Predicted probability of Petition: Interaction between gender and political gender equality. Covariates include age and education level.

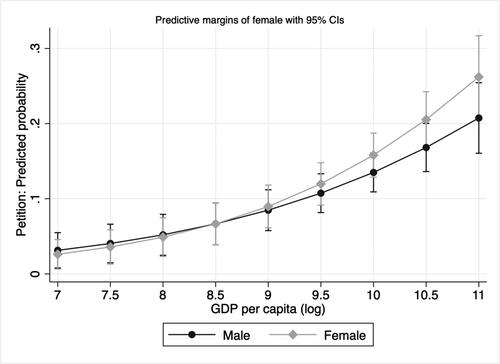

Figure 8. Predicted probability of Petition: Interaction between gender and GDP. Covariates include age and education level.

The results support Hypothesis 2a, though to varying degrees. Looking at and , boycotting has the greatest female-led gender gap, while the gendered positive effect of living in a politically gender equal country is the strongest for petitioning (p < .01). That women are more likely to participate in environmental petitioning in politically gender equal countries implies the presence of gendered opportunities, i.e. in the form of women’s access to education and information, representation, as well as freedom to engage in collective action and political expression of environmental grievances.

Additionally, in line with Hypothesis 2b, the interaction effect of political gender equality was strongest and most statistically significant for the individual and non-confrontational forms, petitioning and boycotting, but also weakly so for protesting (p < .05). This means that in more politically gender equal countries, women are more likely to boycott, sign environmental petitions and to some extent, to protest. In comparison, the effect of female labor force participation, a measure of economic gender equality, was weaker for all forms of EPP, though statistically significant for petitioning (p < .05) and boycotting (p < .01). This implies that countries with high political gender equality as captured by the WPE index are more likely to have gendered opportunities enabling women’s EPP. Note that the number of countries on the lower end of economic gender equality are fewer in this dataset; inclusion of more countries with low female LFP may yield other results. However, illustrates the interaction effect between gender and political gender equality for petitioning, with overlapping 95% confidence intervals that make this interaction effect on petitioning in particular less robust. Further research should therefore look into different political gender equality measures, perhaps with a larger sample of countries to better examine this effect.

Looking at the boycotting interactions illustrated in and , we see a statistically significant effect of equality on EPP. Particularly around the higher values of gender equality, where a higher share of countries in our sample are located, the confidence intervals indicate higher certainty of this effect. Moreover, it is interesting to note the gender differences in the directions of the slopes: It appears that while women in this sample may not necessarily engage more in boycotting when economically empowered by LFP, men’s engagement rather appears to substantially decline in such contexts (though non-significant in the AMEs model). This same pattern is true for protesting, though the differences are very small there. One interpretation of this is that women are fairly consistent in their environmental boycotting regardless of economic independence. To explain this, we reason that in countries with lower female LFP, women are likelier to depend on money from their household (e.g. male bread-winner). In such a situation, their purchasing behavior and boycotting could be subtly merged with their role as a home-maker and care-taker (purchasing groceries, clothes, etc.,) making boycotting a form of EPP they are able to pursue regardless of financial independence. Why men’s individual and non-confrontational EPP in the form of boycotting decreases as female LFP grows could be further explored in future research. However, since probability of boycotting increases by 12 percentage points (p < .001) when a respondent is highly educated, access to higher education – a central gender inequality issue – being a significant predictor may still imply the existence of underlying structural gendered challenges, as well as socioeconomic ones.

Lastly, Models 6 in the tables report interaction effects between being female and GDP. It is valuable to compare the interaction effect between being a woman and gender equality and with GDP. For petitioning (p < .01) and boycotting (p < .001) there are statistically significant effects of being a woman in a country with higher GDP. While it is not too surprising that women are more likely to be informed about and have access to sign environmental petitions in wealthier countries, as gendered opportunity structures would suggest, the gendered effect of gender equality is stronger. However, we find that the effect on both boycotting and petitioning is strikingly similar to that of political, compared to economic gender equality, upon comparing and , and and .Footnote6 We therefore highlight the importance of including different measures of gendered opportunities.

In sum, our results show that women engage significantly more than men in more non-confrontational EPP forms across countries, while they are on par with men’s protesting. An aim and contribution of this study has been to highlight the importance of distinguishing between different forms of EPP and including those favored by women, when examining patterns of engagement. Moreover, the substantial country-heterogeneity in gendered patterns of engagement can be partly explained by considering levels of gender equality, implying the possible presence of gendered opportunities for women to voice their environmental grievances politically.

Limitations

This study has relied on the assumption that the ISSP’s gender variable is reasonably comparable across countries, which due to inconsistent survey design (asking about sex or gender) is less certain. However, since sex and gender presentation overlap in the very large majority of cases (with minorities including intersex and trans persons (Amnesty International Citation2024), the risk of such discrepancies is very small, and we argue that the variable remains useful to discuss large-scale gender inequalities and behavioral patterns across countries.

Another limitation is the relatively small number of environmental protesters in ISSP participant countries, as well as the variation in survey year during different points in the Covid-19 pandemic. Though it is a small minority of countries that were surveyed late into the pandemic, there is a risk that this affected the outcomes. Lastly, other measurements of structural gender equality may capture the interactions with gendered EPP better. This paper attempted to account for political and economic gender equality by considering women’s labor force participation and political rights and representation, but other possibly interesting factors for future research to consider include women’s health care, economic independence, social mobility, or cultural norms.

Conclusions

This study set out to answer (1) Are there consistent gender differences across different forms of environmental political participation? and (2) Does a country’s level of gender equality matter more for women’s environmental political participation than for men’s?, by examining three hypotheses. We make a theoretical contribution to the growing literature on gender gaps in environmental political participation (EPP) by offering a new encompassing approach which conceptually separates different forms of engagement in order to discern gendered patterns. On the micro-level, gender socialization theory was used to explain how women are more likely to engage in individual or non-confrontational forms (boycotting, petitioning) than more collective and confrontational forms (protesting). A key contribution of the study is thus that, in line with Hypothesis 1, women do engage more than men in the majority of the included forms of EPP (boycotting, petitioning), and equally in protesting. Past research has often overlooked women’s preferred forms of engagement, leading to puzzled conclusions in the field that women engage less than men, despite consensus on women’s significantly higher levels of environmental concern and grievances. The results of this study show that more inclusive conceptualizations of EPP helps explain these gender differences.

Concerning the second question, we have shown that country-level differences in gender equality (political, economic) seem to matter more for women’s EPP: That the gendered opportunities brought on by higher levels of gender equality can enable women to voice their environmental grievances. Supporting Hypothesis 2a, results indicate that women are more likely to protest, sign petitions, and boycott for environmental reasons when in more gender equal countries, lending support to the idea that gender equality creates gendered opportunities for women to engage in environmental political action, though substantial variation across countries remains. As expected by Hypothesis 2b, women’s boycotting and petitioning increased in particular. Further exploration of the effects of intersectional individual factors such as ethnic background, or macro-factors such as presence of environmental institutions and policies may also offer insight into who engages in EPP, why, and where.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The author is very grateful to Sebastian Koos and to other colleagues at the Cluster of Excellence “Politics of Inequality” at the University of Konstanz, and to the anonymous reviewers, for their valuable and thoughtful feedback.

Disclosure statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Summer Isaacson

Summer Isaacson is a doctoral researcher at the Cluster of Excellence “The Politics of Inequality” at the University of Konstanz, Germany. Her main research areas include environmental attitudes and behaviors, intersectional environmental inequality, and political participation.

Notes

1 This study focuses on key binary social divisions between men and women. This is due to simplicity and generalization purposes, as well as lack of data on other gender identities.

2 The data that support the findings are openly available: ISSP Environment IV 2020: ZA7650 Data file Version 2.0.0, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.14153 .

3 Voting is a classic form of political participation not included in this study. This is partly due to many political systems among the ISSP participant countries not having a clear “green party/candidate”, making cross-country comparisons both difficult and unreliable. The “green” party may not be the most environmentally friendly, and the most environmentally friendly party may lose environmentally motivated voters due to system-specific structures such as being a periphery party. Additionally, voting is arguably similar to petitioning on our EPP scale (collective and non-confrontational).

4 2022 or 2023: India, Italy, Lithuania, Slovakia, Spain.

5 World Bank data does not differentiate between China and Taiwan. Taiwanese GDP and LFP data are sourced from: CEIC. (Citation2023). Taiwan GDP per Capita. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan. Retrieved 2023-09-01 from https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/taiwan/gdp-per-capita, CEIC. (Citation2023). GENDER AT A GLANCE IN R.O.C. (Taiwan).

6 Due to the similarity in the effects of political equality and GDP in the plots, as an additional robustness test, we ran models 5 again including GDP. In these, the effect of political equality remained strong and significant, while that of GDP vanished. The high correlation values, however, make it hard to draw any certain conclusions from this.

References

- Amnesty International. 2024. LGBTI RIGHTS. Retrieved May 11, 2024 (https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/discrimination/lgbti-rights/).

- Ares, E., and P. Bolton. 2020. The Rise of Climate Change Activism?. House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/the-rise-of-climate-change-activism/

- Awiti, A. O. 2022. “Climate Change and Gender in Africa: A Review of Impact and Gender-Responsive Solutions.” Frontiers in Climate 4: 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2022.895950.

- Balzekiene, A., and A. Telesiene. 2012. “Explaining Private and Public Sphere Personal Environmental Behaviour.” Social Sciences 74(4): 7–19. doi: 10.5755/j01.ss.74.4.1031.

- Birkmann, J., E. Liwenga, R. Pandey, E. Boyd, R. Djalante, F. Gemenne, W. L. Filho, P. F. Pinho, L. Stringer, and D. Wrathall. 2022. “Poverty, Livelihoods and Sustainable Development,” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change C. U. Cambridge, UK | NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Briscoe, Michael D., Jennifer E. Givens, Shawn Olson Hazboun, and Richard S. Krannich. 2019. “At Home, in Public, and in between: Gender Differences in Public, Private and Transportation Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the US Intermountain West.” Environmental Sociology 5 (4):374–92. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2019.1628333.

- CEIC. 2023. “Taiwan GDP per Capita. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan.” Retrieved September 01, 2023 (https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/taiwan/gdp-per-capita).

- Chiu, B. 2019. “The Greta Thunberg Effect: The Rise of Girl Eco-Warriors.” Forbes. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/bonniechiu/2019/09/19/the-greta-thunberg-effect-the-rise-of-girl-eco-warriors/).

- Coffé, H., and C. Bolzendahl. 2010. “Same Game, Different Rules? Gender Differences in Political Participation.” Sex Roles 62 (5–6):318–33. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9729-y.

- Davidovic, D., N. Harring, and S. C. Jagers. 2019. “The Contingent Effects of Environmental Concern and Ideology: Institutional Context and People’s Willingness to Pay Environmental Taxes.” Environmental Politics 29(4):674–96. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1606882.

- CEIC. (2023). "Taiwan GDP per Capita. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan." Taiwan: Department of Gender Equality. (2022). GENDER AT A GLANCE IN R.O.C. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/taiwan/gdp-per-capita.

- Deth, J. W. 2016. “Political Participation.” The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication 1–12. doi: 10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc171.

- Dieleman, R., and F. Andersson. 2016. “Measuring Women’s Political Empowerment and Investigating the Role of Women’s Civil Liberties in Democratization.” U. O. Gothenburg. (https://v-dem.net/media/publications/policy_brief_4.pdf).

- Dietz, T., L. Kalof, and P. C. Stern. 2002. “Gender, Values, and Environmentalism.” Social Science Quarterly 83(1):353–64. doi: 10.1111/1540-6237.00088.

- Dodson, K. 2015. “Gendered Activism.” Social Currents 2(4):377–92. doi: 10.1177/2329496515603730.

- Dzialo, L. 2017. “The Feminization of Environmental Responsibility: A Quantitative, Cross-National Analysis.” Environmental Sociology 3(4):427–37. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2017.1327924.

- Eastin, J. 2018. “Climate Change and Gender Equality in Developing States.” World Development 107:289–305. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.021.

- EIGE. 2022. “Gender Equality Index 2022: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Care.” E. I. f. G. Equality 1–126. doi:10.2839/03588.

- El Khoury, C., A. Felix, J. Lorenzini, and J. Rosset. 2022. “The Gender Gap in Pro‐Environmental Political Participation among Older Adults.” Swiss Political Science Review 29(1):58–74. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12547.

- GESIS. 2023. “ISSP 2020 – Environment IV, Variable Report: Documentation Release 2023/08/25 Related to the International Dataset GESIS Study-No. ZA7650 Version 2.0.0.” GESIS-Variable Reports, Issue. 1–693.

- Giugni, M. 2011. “Political Opportunities: From Tilly to Tilly.” Swiss Political Science Review 15(2):361–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1662-6370.2009.tb00136.x.

- Gundelach, B., and D. Kalte. 2021. “Explaining the Reversed Gender Gap in Political Consumerism: Personality Traits as Significant Mediators.” Swiss Political Science Review 27(1):41–60. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12429.

- Heisig, J. P., and M. Schaeffer. 2019. “Why You Should Always Include a Random Slope for the Lower-Level Variable Involved in a Cross-Level Interaction.” European Sociological Review 35(2):258–79. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcy053.

- Höllinger, F., M. Hadler, and W. Aschauer. 2020. “International Social Survey Programme: Environment IV – ISSP 2020. GESIS, Cologne.” (https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA7650).

- Hooghe, M., and D. Stolle. 2004. “Good Girls Go to the Polling Booth, Bad Boys Go Everywhere.” Women & Politics 26(3–4):1–23. doi: 10.1300/J014v26n03_01.

- Hoominfar, E. (2019). "Gender Socialization". In Gender Equality. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70060-1_13-1.

- Hunter, L. M., A. Hatch, and A. Johnson. 2004. “Cross‐National Gender Variation in Environmental Behaviors.” Social Science Quarterly 85(3):677–94. doi: 10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00239.x.

- ISSP 2023. Environment Gesis, Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. Retrieved March 06 (https://www.gesis.org/en/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/environment).

- Kennedy, E. H., and J. Kmec. 2018. “Reinterpreting the Gender Gap in Household Pro-Environmental Behaviour.” Environmental Sociology 4(3):299–310. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2018.1436891.

- Knight, K. W. 2019. “Explaining Cross-National Variation in the Climate Change Concern Gender Gap: A Research Note.” The Social Science Journal 56(4):627–39. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2018.08.013.

- Koopmans, R. 1999. “Political. Opportunity. Structure. Some Splitting to Balance the Lumping.” Sociological Forum 14(1):93–105.

- Koos, S. 2012. “What Drives Political Consumption in Europe? A Multi-Level Analysis on Individual Characteristics, Opportunity Structures and Globalization.” Acta Sociologica 55(1):37–57. doi: 10.1177/0001699311431594.

- Levy, B. L. M., and M. T. Zint. 2013. “Toward Fostering Environmental Political Participation: Framing an Agenda for Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 19 (5):553–76. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2012.717218.

- Li, D., L. Zhao, S. Ma, S. Shao, and L. Zhang. 2019. “What Influences an Individual’s Pro-Environmental Behavior? A Literature Review.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 146:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.024.

- Mandel, H., A. Lazarus, and M. Shaby. 2020. “Economic Exchange or Gender Identities? Housework Division and Wives’ Economic Dependency in Different Contexts.” European Sociological Review 36(6):831–51. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcaa023.

- Marien, S., M. Hooghe, and E. Quintelier. 2010. “Inequalities in Non-Institutionalised Forms of Political Participation: A Multi-Level Analysis of 25 Countries.” Political Studies 58(1):187–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x.

- Masad, R. 2020. “The struggle for women in politics continues.” https://www.undp.org/blog/struggle-women-politics-continues

- McAdam, D. 1996. “Conceptual Origins, Current Problems, Future Direction.” Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements 23–40. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511803987.003.

- McCammon, H. J., K. E. Campbell, E. M. Granberg, and C. Mowery. 2001. “How Movements Win: Gendered Opportunity Structures and U.S. Women’s Suffrage Movements, 1866 to 1919.” American Sociological Review 66(1):49–70. doi: 10.1177/000312240106600104.

- McCright, A. M., and C. Xiao. 2014. “Gender and Environmental Concern: Insights from Recent Work and for Future Research.” Society & Natural Resources 27(10):1109–13. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2014.918235.

- Mohai, P. 1992. “Men, Women, and the Environment: An Examination of the Gender Gap in Environmental Concern and Activism.” Society & Natural Resources 5(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/08941929209380772.

- National Intelligence Council. 2021. “The Future of Women’s Rights.” Retrieved August 03, 2023 (https://www.dni.gov/index.php/gt2040-home/gt2040-deeper-looks/future-of-womens-rights).

- Noth, F., and L. Tonzer. 2022. “Understanding Climate Activism: Who Participates in Climate Marches Such as “Fridays for Future” and What Can we Learn from It?” Energy Research & Social Science 84:102360. 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102360

- Polyas 2023. Petition. Retrieved October 01, 2023. https://www.polyas.com/election-glossary/petition

- Ramstetter, L., and F. Habersack. 2019. “Do Women Make a Difference? Analysing Environmental Attitudes and Actions of Members of the European Parliament.” Environmental Politics 29(6):1063–84. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1609156.

- Schaftenaar, S. 2022. "Gender Equality and Conflict Gendered Determinants of Armed Conflict, Violent Political Protest, and Nonviolent Campaigns" [Dissertation]. pp. 1–56.

- Schumacher, I. 2014. “An Empirical Study of the Determinants of Green Party Voting.” Ecological Economics 105:306–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.05.007.

- Shayegh, S., and S. Dasgupta. 2022. “Climate Change, Labour Availability and the Future of Gender Inequality in South Africa.” Climate and Development 16 (3):209–26. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2022.2074349.

- Snow, D. A., and S. A. Soule. 2010. A Primer on Social Movements. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Steenvoorden, E. 2018. “One of a Kind, or All of One Kind? Groups of Political Participants and Their Distinctive Outlook on Society.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 29(4):740–55. doi: 10.1007/s11266-018-0002-2.

- Stern, P. C. 2000. “New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior.” Journal of Social Issues 56(3):407–24. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00175.

- Strumskyte, S., S. Ramos Magaña, and H. Bendig. 2022. Women’s Leadership in Environmental Action. Paris, France: OECD.

- Sultana, F. 2013. “Gendering Climate Change: Geographical Insights.” Professional Geographer 66(3):372–81. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2013.821730.

- Tarrow, S. 1996. “States and Opportunities: The Political Structuring of Social Movements.” Pp. 41–61, in Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements, edited by D. McAdam, J. McCarthy, & M. Zald. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Tindall, D. B., S. Davies, and C. MauboulÈS. 2003. “Activism and Conservation Behavior in an Environmental Movement: The Contradictory Effects of Gender.” Society & Natural Resources 16(10):909–32. doi: 10.1080/716100620.

- Trelohan, M. 2021. “Do Women Engage in Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Public Sphere Due to Social Expectations? The Effects of Social Norm-Based Persuasive Messages.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 33(1):134–48. doi: 10.1007/s11266-020-00303-9.

- Tschakert, P., K. Zimmerer, B. King, and S. Baum. 2023. Individual vs. Collective Action Penn State, The College of Earth and Mineral Sciences. Retrieved August 28, 2023 (https://www.e-education.psu.edu/geog30/node/346).

- UNFCCC. 2022. Dimensions and Examples of the Gender-Differentiated Impacts of Climate Change, the Role of Women as Agents of Change and Opportunities for Women. U. N. F. C. o. C. Change.

- UNWomen 2022. “Explainer: How Gender Inequality and Climate Change are Interconnected. Retrieved January 26 (https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2022/02/explainer-how-gender-inequality-and-climate-change-are-interconnected).

- UNWomen 2023. “Women’s Leadership and Political Participation. UNWomen.” Retrieved September 19, 2023 (https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation).

- Winkler, A. E. University of Missouri-St. Louis, USA, and IZA, Germany. 2022. “Women’s Labor Force Participation.” IZA World of Labor 1–11. doi: 10.15185/izawol.289.v2.

- Wolak, J. 2020. “Conflict Avoidance and Gender Gaps in Political Engagement.” Political Behavior 44(1):133–56. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09614-5.

- Workman, B., C. Pascoe Leahy, J. Peel, K. Bowen, and R. Markey-Towler. 2022. Women Leading the Fight Against Climate Change. https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/women-leading-the-fight-against-climate-change/

- World Bank Group 2023a. GDP per capita (current US$). Retrieved November 20, 2023 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?view=map&year=2018).

- World Bank Group 2023b. Metadata Glossary. Retrieved November 20, 2023 (https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/statistical-capacity-indicators/series/5.51.01.10.gdp).

- World Bank Group 2023c. Ratio of Female to Male Labor Force Participation Rate (%) (Modeled ILO Estimate). Retrieved November 20, 2023 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FM.ZS?view=map&year=2018).

- World Economic Forum. 2022. Global Gender Gap Report.

- Yang, P. Q., and M. L. Wilson. 2023. “Explaining Personal and Public Pro-Environmental Behaviors.” Sci 5(1):6. doi: 10.3390/sci5010006.

- Zelezny, L. C., P.-P. Chua, and C. Aldrich. 2000. “New Ways of Thinking about Environmentalism: Elaborating on Gender Differences in Environmentalism.” Journal of Social Issues 56(3):443–57. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00177.

- Zhou, L., D. S. Kori, M. Sibanda, and K. Nhundu. 2022. “An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa.” Climate 10(8):118. doi: 10.3390/cli10080118.