Abstract:

A clear sign of the heightened interest in economic inequality was the surprising popularity of Thomas Piketty's book, Capital in the Twenty‐First Century, presenting a dense synopsis and major contribution to the economics of inequality. This article investigates discourses on inequality in news media, through the highly controversial debate raised by Piketty's best‐selling book, in selected print media in four European countries.

We conceive of the media as having an impact on the perceptions and knowledge of economic processes #thus influencing preferences of the public for economic policy making. This is in line with Veblen #who terms the press an “educational system.” Regarding the topics of inequality; we will show that media coverage leads to a biased picture of both inequality and the role of redistribution policies to possibly curb such a development

A significant characteristic of economic development in the past decades has been the rise in inequality. Widening income gaps, falling wage ratios, and the ever‐increasing accumulation of wealth (especially by the top 1% or even 0.1%) are just some of the key quantitative indicators of this transformation. After decades of benign neglect, the issues of economic and social inequality have re‐entered the stage of mainstream political attention and debate in the Western heartland in the past couple of years. This is no accident or surprise, as this renewed attention is unfolding against a backdrop of a very slow, patchy, and highly uneven recovery from the major financial crash in the North Atlantic core region in 2008.

Economic discussions concerning questions of economic inequalityFootnote1 focus on its quantitative evaluation (Galbraith Citation2012; Antonelli and Rehbein Citation2018). The topic of how those research findings are mediated to the public is barely addressed. This communication refers to how non‐experts are informed and how their notions of economic inequality are being framed. It is especially important to raise these questions, because the acceptance of redistribution policies correlates with the concept of inequality people have in mind (Gimpelson and Treisman Citation2018).

This article problematizes the information news media provides—to the public, to the consumers of news media—about economic inequality and possible remedies thereof. In our understanding, the mass media plays an indispensable role for the creation and dissemination of ideas and opinions related to economic processes and their material outcomes—be it for knowing and accepting public policy options or the results of scientific research. Such a construction of reality is what a leading media scholar explains by saying, “the mass media play a central role in shaping public tolerance of different forms of inequality” (Gandy Citation2007, 3).

Media does not only serve an information function, but also plays a decisive role in shaping opinions and outlooks, for example, concerning the acceptance of redistribution policies (Grisold and Theine Citation2017). For the purposes of this article, Thomas Piketty's book Capital in the Twenty‐First Century (hereafter referred to as C21) is treated as a paramount example of the mediation (in the German sense of “Vermittlung”) of economic inequality in the public sphere. We aim to shed light on the hitherto rather neglected topic of media coverage of economic inequality, thus seeking to analyze the intricate ways in which discourses on inequality and redistribution policies are shaped in the public debate.

The article is structured as follows: The next section introduces the methodology and data used, and gives a short overview of the research project this article is based upon. Thereafter we present the theoretical embedding, in particular the concept of endogenous preferences and Veblen's reflections on media as “pecuniary businesses.” We then move on to present our empirical work systematizing the media discourses on inequality: To investigate and debate the—ideological as well as pragmatic—treatment of economic inequality and the discourse on redistribution policies. The final section synthesizes the respective findings with our theoretical considerations and presents conclusions.

Research Questions, Data, and Method

This article is based on the research findings of an international and transdisciplinary project on the media coverage of economic inequality entitled “The Mediation of Economic Inequality. Media Coverage of Piketty's Book Capital in the 21st Century” (Grisold et al. Citation2017; for a recent publication see Grisold and Preston Citation2020).Footnote2 In this research, Thomas Piketty's book was treated as a paramount example of the mediation of economic inequality to the public sphere, therewith shedding light on the neglected topic of media coverage on economic inequality. As a major transnational and cross‐disciplinary study in scope, it analyzed the highly controversial discourse on inequality topics raised by Piketty's best‐selling book in selected print media in four European countries: the UK, Ireland, Germany, and Austria.

The book by Piketty presents a dense synopsis and major contribution to the economics of inequality, therefore it may well serve as a leading model or example of the current public debates on the scope, measures, meanings, and implications of economic inequality. The book and its central messages have become highly popular, provoking lively debates and controversy in economics, the social sciences, and in the public debate. “Now, What Exactly is the Problem?” the title of this article, is citing a newspaper article (Ortner Citation2014, 39) strongly opposed to Piketty's work.

In this article, we focus on the following key questions:

(1) What are the main stances on economic inequality depicted in the media coverage?

(2) How does media coverage portray and judge potential redistribution policies?

To address and answer those questions, our research covers two different language regions (the English and German language discourse) as well as a good mix of “big” and “small” polities in the European Union setting.Footnote3 In each country, two dailies that are classified as quality newspapers, and one major general interest weekly paper (see ) were analyzed in the time period between March 2014 and March 2015. This coincided with the publication of the English translation of C21 in April 2014 and the German translation the following October. The period also coincides with Piketty's C21 promotional tour to Ireland, the UK, Austria, and Germany.

Methodologically, we used a method rather uncommon to economists to investigate economic issues, but of major relevance for our specific topic. We applied critical discourse analytic approaches (CDA) (Wodak and Meyer Citation2009) to analyze our research questions. CDA investigates the linguistic elements of discourse in their wider social and political contexts. Thus, it is not a study of language per se, but rather the use of language, in our case to frame economic inequality in the press.Footnote4

Table 1. Selected NewspapersFootnote5

From the varying scope of different forms and practices, we concentrated on CDA in the tradition of Siegfried Jäger (Citation2015), whose methodological approach enables researchers to cover mid‐size text corpora (as is the case for our research) and to maintain a qualitative approach indispensable for capturing textual meanings, both manifest and latent. Following Jäger (Citation2015), we considered all relevant articles (the whole discourse) in a structural analysis and also performed a detailed (fine grain) analysis for specific, highly relevant aspects and texts (Jäger Citation2015). Based on Teun Van Dijk (Citation2004) and Theo Van Leeuwen (Citation2005), we also focused on “legitimation,” defined as textual and speech strategies by which opinions are justified and interests promoted. In line with Thomas Huckin (Citation2002), we investigated various “significant silences” in the corpus; that is, important issues ignored in the newspaper texts which would be considered decisive factors when discussing growing inequality and redistribution policies.

The corpus was taken using the keyword “Piketty” in searches of Lexis Nexis and other databases.Footnote6 Of the 441 articles for all four countries (Germany 121, Austria 95, UK 160, Ireland 65) and after a correction of the gratuitous ones, the final corpus comprised 329 articles (76 from Germany, 75 from Austria, 118 from UK, and 60 from Ireland). A complex and detailed coding scheme was developed to be applied to the corpus of twelve newspapers with the help of the qualitative data analysis software MaxQDA. All articles were read and manually coded accordingly.

Conceptual and Theoretical Embedding

The empirical findings are embedded in two conceptual theoretical approaches in order to shed light on the impact of the media on perceptions of economic inequality and preferences for economic policies. Out of the many possible theories on media, in the following we present two concepts vital to the topic of this article, to (1) understand the consequences of media coverage (endogenous preferences) and (2) to contextualize the restrictions for the informational role of the media (the Veblenian perspective that comprehends media as both educational and a pecuniary business).

Our starting point is that media have an influential impact on perceptions and knowledge of economic processes and consequently influence the preferences of the public, (e.g., for economic policy‐making) (Grisold and Theine Citation2017). This basic understanding of preferences is in line with what has been termed endogenous preferences by several (heterodox) economists. Factors affecting endogenous preferences are created within—and not outside—the economic system. Therefore, economic institutions may (and actually do) influence individual preferences.

A seminal contribution in this regard has been made by Bowles and colleagues, but with only one very cursory remark to the media as part of this endogeneity. They demonstrated that markets—as well as other economic institutions—are able to affect endogenous preferences directly through the framing and construal of situations, the structuring of rewards and incentives, the evolution of norms, and task‐related learning, as well as indirectly through the process of cultural transmission itself (Bowles Citation1998; Bowles 2008; Bowles and Polania‐Reyes Citation2012). Likewise, but from a more mainstream, behavioral economics point of view, Daniel Zizzo argues that when decision‐makers repeatedly face new situations, they shape their preferences in interaction with the market setup (Zizzo Citation2003, Citation2005) through a learning process.

Cultural determinants as a formative principle of endogenous preferences were already addressed eloquently by Thorstein Veblen (Citation1904) in combination with a further influencing factor that is especially vital in the media context: advertisement. The two factors have been analyzed in more depth, albeit in a slightly different vein, focusing on corporate structures—by John Kenneth Galbraith (Citation1970a). For Veblen, “conspicuous consumption” was a cornerstone of an unequal, hierarchical, consumerist society, with the lower classes emulating the lifestyle and consumption patterns of the leisure class (see also Bowles and Park Citation2005). According to Galbraith, corporate capitalism brings about a different kind of influence: an institutionalization of the endogenous formation of preferences, that is, a development of the institutional capacities of the producer for forming preferences. The potential of corporations to create consumer demand for their products (through advertising) was, for Galbraith, a key mechanism of the “affluent society”: Corporate capitalism adds a set of institutions, bureaucracies, and planning facilities specifically for forming preferences (Galbraith Citation1958; Zucker Citation2001; Fullbrook Citation2003), thereby causing further problems of the affluent society of capitalism.

Yet, only a few of those economists that deal with endogenous preferences refer to the role of mass media in the processes of endogenous preference formation (Grisold Citation2004; Grisold and Theine Citation2017). And indeed, it is not the easiest of tasks. Whenever the importance of media is to be highlighted, the renowned German sociologist Niklas Luhmann's notorious quote is frequently cited: “Whatever we know about our society, or indeed about the world in which we live, we know through the mass media.” (1996, 1) Alas, the sequitur in Luhmann's text is referred to with less frequency: “On the other hand, we know so much about the mass media that we are not able to trust these sources” (1996, 1). It is in exactly this ambivalence and contradictory nature of the media that the central relevance of media manifests itself: The role of mediation is inscribed in mass media, but also its flaws of partisanship, one‐sidedness, and selectivity.

In this article, we perceive the role of mass media as that of a provider of information, misinformation and all the in‐betweens as a starting point.Footnote7 More specifically, in the case of economic issues, the media plays a key role as a conveyor and reinforcer of dominant societal norms and narratives (Leitbilder). These norms include keeping up with the Joneses, which influences both consumption decisions and—on a much more general level—identity by displaying advertisements or spreading political opinions, often in exactly this conjunction. In the field of economic inequality, the role of the mass media has proven decisive for making sense of economic disparities, given the low levels of interaction amongst citizens from different socioeconomic backgrounds. The shaping of preferences through mediation to achieve the acceptance, introduction, or change in economic public policies is thus an important issue to be addressed within the context of economic inequality.

Regarding the role of the media for shaping endogenous preferences, there are only very few empirical studies on (see Grisold and Theine Citation2017 for a review). They identify a clear tendency with regard to inequality: media “may act as an intermediary between distributional outcomes and public opinion” (Kelly and Enns Citation2010, 869), and shed a rather unfriendly light on the information context, for example of (in this case: George W. Bush's) tax reforms: “Rife with ambiguity and sweeping generalities, the reporting failed to help those at varying income levels evaluate what share of the tax cuts they would receive—if any” (Bell and Entman Citation2011, 563).

From the vast pool of literature on the media industries (see for an overview Grisold Citation2004; Albarran Citation2016; or Holt and Perren Citation2009), we want to introduce an early institutional perspective that follows the line of argument on endogenous preferences presented above: Veblen conceived the “periodical press”Footnote8 as a strand of the “educational system” (Veblen Citation1904, 129) at the same time as being a business enterprise. We conceive the media in Veblenian terms as news organizations embedded in a capitalist economic system and, thus, as pecuniary business enterprises that subordinate public service interests to profitability considerations (Veblen Citation1904, 130; Champlin and Knoedler Citation2002, Citation2008). This transforms media into “vehicles for advertisements” (Veblen Citation1904, 129) structurally dependent on ad‐sells as a main source of revenue.Footnote9 Turning to Galbraith's arguments once again, the corporate structure of media enterprises is of major importance. News in the new age of media conglomerates is in the hands of a few mega‐corporations. What Ben Bagdikian (Citation2004) meticulously showed in his research is largely confirmed and supported by the findings of more recent publications (for example Bettig and Hall Citation2012; Noam Citation2016, Birkinbine, Gómez and Wasko Citation2017).

Veblen, concluding his contribution on media businesses, comes back to the “teaching aspect” of the press: “The trend of its teaching, therefore, is, on the whole, conservative and conciliatory” (Veblen Citation1904, 131). There is, after all, a twofold meaning to this statement: news content does not tell the truth, but it tells readers what they want to hear,Footnote10 and it is designed not to insult or offend (potential) advertisers.

The dichotomy discussed here is still valid more than a century later: critical political economy (of the media) and critical media studies acknowledge the fact that media will not cater against the interests of their advertisers, as they have to cater to the tastes of their readers as well, and should not anger their owners (for an overview, see Grisold Citation2004). Furthermore, media content has been shifting towards a supply of infotainment, while the supply of serious news and investigative journalism is decreasing: “the quantity and content of the news supplied by the mainstream press has been tilted toward news that is sensationalistic, ratings‐enhancing, and cheaply produced” (Champlin and Knoedler 2008, 144). Both aspects tend to be further amplified by the ongoing merger of media corporations into multimedia conglomerations: “news operations as mere adjuncts to larger entertainment enterprises, whose main business is to make money, not to produce media content that is useful to the citizenry” (Champlin and Knoedler 2008, 144).

The Discourse on Economic Inequality in the Press

contains the number of newspaper articles grouped according to their attitude towards economic inequality within the period of analysis (March 2014 to March 2015). In total, we found 178 articles with an explicit stance on economic inequality. Although the remaining 151 articles in our sample do report about Thomas Piketty, C21, and the great inequality debate, they do not explicitly take any position on economic inequality. Such articles, for instance, report only the key figures and statistics given in C21.

With respect to the corpus of 178 articles, there are 108 articles which consider economic inequality a problem, while 51 actually portray inequality as not being a problem and another 19 remain neutral. There was no significant time difference for the stance towards inequality, except for many articles appearing in May and October 2014 (the publication dates of the English and German version of the book).

Table 2. Number of Newspaper Articles by Stance Towards Economic Inequality

also sheds light on the differences in the Piketty reception across the four countries. In the English‐speaking countries, and to a lesser extent also in Germany, the number of articles which portray inequality as problematic is higher compared to the ones which don't. While there are several articles of the latter kind in Germany and the United Kingdom, the Irish coverage seems to be overtly pro‐Piketty even though past research has insisted on the usual neo‐liberal framing in Ireland, including opposition to interference in markets and explicit market and business orientation (Preston and Silke Citation2011; Silke and Graham Citation2017). Austria marks a striking difference, as the number of articles that do not assess inequality as a problem outnumbers the reverse category.

An analysis of media content () shows that the positions stressing the problematic aspects of inequality are, as was to be expected, markedly higher in all center‐left/social‐liberal newspapers (The Guardian, Irish Times, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Der Standard)—this holds true for all of the four countries in question. By contrast, the total number of articles that assess inequality as unproblematic is comparably high in center‐right/ market‐liberal newspapers (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Die Presse, Financial Times, and Sunday Times). With regard to the weekly or Sunday papers in our sample, only the Murdock‐owned Sunday Times is highly critical of Piketty's problematization of inequality. Again, Ireland seems to represent a specific case as the Irish Independent, a rather conservative outlet, does not contain articles uncritical to economic inequality.

Concerning authorship, almost 80% of the articles were written by staff or freelance journalists, while the remaining 20% are opinion pieces or regular columns, most of them written by economists. And it is rather stunning that 80% of the authors are of male sex.

The Framing of Economic Inequality

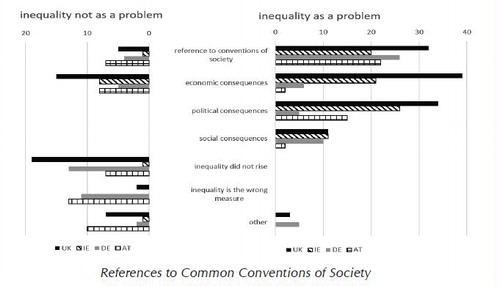

We continue with an analysis of the specific framings of inequality—that is, all coded segments which display a standpoint towards inequality (all these segments are contained in the articles summed up in the first three lines in ). shows the most frequent categories, thus frames, used in the texts analyzed. As with the stance towards inequality, we also encounter more coded segments which view inequality as a problem in comparison to those expressing contrary attitudes.

References to Common Conventions of Society

Considering the distribution of the different categories, reference to common conventions of society is the topic most frequently discussed in articles on the good or bad of economic inequalities. In this category, the following societal conventions and Leitbilder are referred to: social justice, social mobility and meritocracy, the latter being the most frequently‐used in quantitative terms.

Meritocracy, in its essence, refers to the idea that effort and talent should be the primary indicator for higher income and wealth, closely connected to success in the social hierarchy. It is crucial to note that in almost all articles, individual effort is equated to “hard work,”Footnote11 rewarded through markets and attributed to individual efforts. Thus, neither questions of group efforts, which might not be assigned to individuals exclusively, nor unpaid work are considered relevant—with the exception of only one article out of the entire sample.

Within the body of articles which highlight problems of rising inequality, it is widely acknowledged that individual efforts and the appropriate remuneration in terms of wealth, income, and—sometimes—societal status actually do diverge. The significant tendency identified is that, instead of effort and talent, it is inheritance and birth that determine social status. Individual wealth based on inheritance is sharply criticized, for example, in the Süddeutsche Zeitung: “birth is a lottery, not a merit”Footnote12 (Schulz Citation2014).

Closely connected to the meritocracy topic is the widespread view that social justice is synonymous to equality of chances. In this context, it is implied, on the one hand, that the rich are self‐made men who start without any wealth to back them up, and have achieved their wealth through talent and initiative. On the other hand, the argumentation strategy stresses the opinion that reality simply does not correspond with the ideal of equality of chances.

All in all, and in line with the normative principle of a presumed meritocracy, the problem of growing inequality tends to be interpreted under the paradigm of whether or not meritocracy leads to unequal opportunities. The existence of economic inequality is considered legitimate as long as justice is guaranteed through equality of opportunities. Accordingly, the highly uneven distribution of inheritances is identified as the main obstacle: “You inherit not only wealth but also opportunity” (Monbiot Citation2014, 29), thus resulting in “unearned privileges”; even the “best educated have no chance if they start without wealth.” Hence, we discern a common pattern, namely that it is not equality per se which is aimed for, but rather the lack of functioning meritocratic principles is highlighted, either as a factual threat these days, or as a problem in the near future.

But I suspect that the real reason for Piketty's rock‐star reception is not the quality of his numbers but the fact that he has forced Americans to confront a growing sense of cognitive dissonance. Nearly two‐and‐a‐half centuries ago, […] they proudly believed they had rejected Europe's tradition of inherited aristocracy and rentier wealth. Instead, it was presumed that people ought to become rich through hard work, merit and competition. (Eley Citation2014)

Not very surprisingly, in those articles which portray inequality as not problematic, the reference to common, societal conventions and, again, meritocracy turns out to be a central argument for the sheer necessity of economic inequality. If inequality is an outcome of merit due to equal opportunities and thus equality of chances, then—in contrast to its threatening potential—it is something that actually should be celebrated. In general, if inequality is a market outcome, there is nothing much we can/or should do about it. On the contrary, it can serve as an incentive to take risks and—as a consequence—be rewarded with economic success.

… dass ein gewisses, beträchtliches Maß an Ungleichheit wirtschaftlich gesund ist. Die Aussicht, reich zu werden, treibt ganz klar viele Menschen zu harter Arbeit an. (John Citation2014, 2)Footnote13

In the German articles of this type, the historical perspective is quite prominent. The claims are that the middle class profited most from economic progress over the decades, that capitalism was characterized by a higher degree of inequality a century ago, and that the privileges of the rich have been shrinking for decades, leaving the rich less “better‐off” than ever before in history (see also the following section).

Be it affirmative or critical articles, the normative frame is still straightforward: meritocracy is taken as essential, indeed a driving force of—and for—our society. Its core function is often defined as a key normative factor of the prevailing societal system.

Economic Consequences

The economic consequences of inequality, the second most common category in quantitative terms, is likewise taken up by articles which conceive of inequality as a problem and those displaying the reverse argumentation. In both types, this category features prominently as it holds approximately a third of the overall number of coded segments. Articles of this category are often concerned with the consequences of (rising) inequality for economic growth, while the respective arguments are usually dichotomous or in polar opposition to each other.

On the one hand, the line of argument is that increasing inequality will negatively affect the economy, and in particular its growth rates. Redistribution measures to relieve inequality consequently turn out to be a productive way to restore positive and high growth rates as well as a stable economy:

“The implication is perhaps surprising. Not only does inequality damage growth, but efforts to remedy it are, on the whole, not harmful. The findings suggest that trade‐offs between redistribution and growth need not be a big worry.” (Martin Wolf, The Irish Times, April 23, 2014)

Not surprisingly, arguments make use of the reverse causality, namely that high inequality does not harm growth, but is instead an important prerequisite to ensure high growth rates. Here, the argument is that inequality and the concentration of capital is actually indispensable for high growth rates, as this provides a solid base for investment and rewards incentives.

Those argumentative strategies often stress the importance of capital and wealth for private investment and risk‐taking. Wealth then is portrayed as “highly productive” capital which is tied up in small and medium‐sized businesses and is thus essential for the well‐being and functionality of the whole of society.

Some of the articles also question the causality of low growth rates as triggers for higher inequality, as this Financial Times article shows:

The theoretical argument that wealth inequalities are likely to rise if growth rates are weak is also dubious. As Prof Lawrence Summers has argued, there are deep questions regarding the likely return to capital in coming decades and whether it will be reinvested to provide a rentier income. (Financial Times Citation2014, 6)

Apart from the dispute over the mechanisms between growth and inequality, there is another relevant, recurring economic topic, namely that inequality poses a problem for employment conditions. Particularly, UK articles frequently assess rising inequality as immersed with impacts on employment conditions, because workers are increasingly being forced to accept lower working standards as well as lower wages due to increased competition. This debate is almost non‐existent in German articles, even though the empirical evidence for deteriorating working conditions (low‐paid sector and one‐euro jobs especially in Germany) is to be found in those countries as well.

With regard to arguments against this, there is one peculiar economic rationalization characterizing articles from all four countries in question: the claims that inequality produces growth, that the poor are actually dependent on the rich, and the rich “create value for other people.” Semantically positive descriptions of agents are being introduced, such as wealthy entrepreneurs “transferring wealth,” “taking risks,” and “creating jobs.” The underlying—and very explicit—rationale being that if politicians were to follow Piketty's call to “slap huge taxes on the rich, […] they will find that it comes back and bites them.” (Smith Citation2014, 16). One further example of this argumentation strategy: starting off with growing inequality of income and wealth as a fact, one article immediately qualifies this statement by announcing it was only the super‐rich that gained. Still, the conclusion is that there is a public “indisposition” about growing inequality, causing discomfort (“öffentliches Unwohlsein”), therewith discrediting this as a feeling the public displays that is not based on reality.

Political and Social Consequences

The categories political consequences and social consequences are only taken up in articles which evaluate inequality as a problem. In articles addressing political consequences, the instability and erosion of democratic structures driven by rising inequality is a major concern. Two processes highlighted frequently in such contributions are, on the one hand, the increasing concentration of political and economic power in the hands of a small elite with rising influence on political decisions and processes. On the other hand, the risk that the legitimation of democratic structures might deteriorate (further) due to the inaction of democratic governments to reverse current trends of increasing inequality, which is said to play into the hands of the populist parties. However, even though such rather complex political currents and processes are addressed and discussed in a set of articles, they remain abstract and intangible, as the narratives usually fail to contextualize the problem in a national context and remain on a very abstract level.

All in all, it came as quite a surprise that social consequences were far from being a prominent topic in the articles discussing inequality as problematic. Nonetheless, rising poverty and demanding healthcare issues are discussed as a consequence of growing inequality—both topics that figured prominently in the work of Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett (Citation2009) and were hotly debated at the time of its publication. In present discourse though, they seem to be losing relevance and becoming marginalized.

Yet, there is a common feature in almost all of the texts: the power of the rich, which can be labelled a “significant silence.” In the corpus at hand, the rich are mostly addressed in statistical terms, such as “the richest 10%,” “the 1%,” “the richest decile,” or “the top 3% of households” who earn or possess large shares in total income or wealth. In the articles concerned about rising inequality, the rich are framed as the main beneficiaries of recent economic developments, as they were able to acquire a greater share of wealth and income. However, evidence of an active role of the rich in this very process is not exactly abundant. Rather, the way they are portrayed suggests they might have little or nothing to do with the growing material divides. This is well in line with earlier studies, for example on the media coverage of executive pays and the super‐rich (Thomas Citation2016; Jaworski and Thurlow Citation2017), which testify paradigmatically to the fact that broader issues concerning capitalist structures and economic inequality have been largely ignored. Hence, what we see is a disabling absence of reference to the interconnectedness of political and economic spheres. The role wealthy people assume in determining rules and regulations, consequently resulting in increasing wealth and income, remains significantly unmentioned in all but a very few contributions.

Inequality Did Not Rise—Inequality Does Not Matter

The lines of argumentation inequality did not rise and inequality does not matter only come up in articles that do not portray inequality as a problem (something that goes without saying). Both categories are similar insofar as they question the database as well as the general focus of Piketty's work and the subsequent debate. Yet, they are also distinctively different in a certain way: in inequality did not rise Piketty's data set and his method are explicitly challenged. We will exemplify this category by the—at the time, widely discussed and thus “famous”—Giles debate. The economics editor of the Financial Times, Chris Giles, criticized Piketty's data work in a headline story on May 24, 2014 and claimed that there are “[…] mistakes and unexplained entries in his spreadsheets.” Several articles restated the initial criticism. Piketty replied with a detailed online ten‐page statement also published as a blog post (Huffington Post), arguing that the criticism of data issues is plainly wrong and his findings are supported by other recent studies (e.g., Saez and Zucman Citation2014). This debate was also taken up by various other newspapers in our corpus where some (e.g., Sunday Times) only reported the initial criticism, but did not follow up on the response by Piketty. A second frequent line of criticism within the argument “inequality did not rise” targets Piketty's central formula r>g. This debate is particularly prominent in Germany, where the controversy around r>g is largely driven by German economists who happen to be especially critical of Piketty's work (see also Bank Citation2016).

Within the category inequality does not matter Piketty's data and formulas are not explicitly criticized, but his focus on income and wealth inequality is called into question. The category of articles arguing that inequality exists and is increasing, but that it is meaningless can be illustrated by the following in‐depth‐analysis of one of the articles. Written by Patrick Bernau (Citation2014, 21), head of the online economics and finance reporting at Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), the argumentative strategy is that inequality is not important, because all living standards are so high that it does not matter. He trivializes today's inequality as “wealth has never been so useless” (“Reichtum war noch nie so nutzlos”). In his view, the “benefits” of capitalism are widely shared across the different classes due to technical innovations and the internet. The fact that virtually everybody is equipped with a mobile phone is taken as a proof that technology is converging living standards on a big scale, since the use of “Google, Facebook and Wikipedia is free for everyone.” However, Bernau does not discuss the fact that the tech giant monopolists like Google, Facebook, etc. hardly pay taxes on the huge profits they generate.

In a kind of Utopian gesture, Bernau outlines the image of a brave new world of unregulated capitalism, where class differences do exist (he even identifies them accordingly), but only by the means and effects of education and knowledge (Bildung). In any case, class is self‐imposed, as exemplified in a black and white metaphor: “Do those who profit from the internet watch a Harvard‐lecture free of charge, or do they waste their time playing the most recent online games?”Footnote14 (Bernau Citation2014, 21).

What to Do Against Rising Inequality? How to Deal with Redistribution Policies?

In this section we analyze the ways redistribution policies are portrayed in the corpus. After introducing a short quantitative section on what types of redistribution policies are mentioned or discussed, we move on to answer the question of what rationales are used. Likewise instructive are the underlying economic theories that guide the media coverage of redistribution policies.

To start with, it is mostly taxes that are addressed in accordance with Piketty's well‐known arguments that new forms of wealth taxation are an essential starting point for any effective strategy to reverse the unbroken trend towards economic inequality in recent decades. Piketty (Citation2014) devotes part four called “Regulating Capital in the Twenty‐First Century” (471–570) to reflections on the welfare state, redistribution policies and public debt. In this section of the book, he proposes a more progressive tax regime with top income taxes of 80% applicable to annual salaries from EUR 500,000. He also recommends a global wealth tax of 1% or 2% to tackle the threats posed by rentiers as the “enemy of democrac[ies]” (422) or the “society of supermanagers” (265) to modern democracies. Piketty further discussed other policies such as minimum wages and the future of pay‐as‐you‐go pension systems; those are hardly (or not at all) addressed in our corpus.

A number of scholars agree with Piketty that substantially higher taxes on income and wealth are a key mean to reduce economic inequality (for instance: Atkinson Citation2015; Galbraith Citation2014). And indeed, there are arguments for enhanced redistribution policies: improvement of equal opportunity and meritocracy, a countervailing power to growing inequality, higher state revenues, as well as being supportive of economic stability. Still, inequality has not increased simply due to tax policies, but is the consequence of a many‐faceted mix of policy decisions directed against the middle and working classes (Mishel, Schmitt, and Shierholz Citation2014). Accordingly, a full list of policies to reduce inequality would have to include labor market reforms as well as a strengthening of countervailing powers (see Theine and Grabner Citation2020 for details).

Returning to our corpus, a first, yet significant observation is that redistribution policies are less frequently addressed compared to economic inequality topics (see ). While 178 articles discuss economic inequality, a total of 143 refer to redistribution policies, moreover, in a less positive framing than economic inequality. Only thirty‐five out of the overall 329 articles agree with intensified redistribution policies, whereas the thrust of fifty‐seven articles is overtly hostile.

There is a general pattern to be discerned that is valid for all of the four countries of our analysis. All of the papers that published a majority of articles that rejected the idea of inequality being a problem (Sunday Times, FAZ, and Die Presse) are likewise hostile to the idea of increasing redistribution policies. Although there is one notable exception: The Süddeutsche Zeitung, very much in favor of debating inequality as a problem, at the same time denounces redistribution measures in a distinct manner. One possible interpretation of this rather uncommon phenomenon may be: although a clear uneasiness over economic inequality is in line with the newspaper's social‐liberal orientation, its specific attitude towards redistribution can be reasonably explained in Veblenian terms: a pecuniary business should not anger its advertisers. also shows that the negative assessment of redistribution policies is driven particularly by articles in the German Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the Austrian Die Presse, both with an explicit market liberal (sometimes: market radical), employer‐friendly stance.

A specific look at the redistribution policies discussed shows that there is yet another pattern to be identified. Articles expressing a negative stance towards Piketty's policy proposals frequently discuss redistribution measures such as taxation of the rich/higher tax rates in general, without further specifying the different forms of wealth and income taxation. Of all specific policies deprecated, wealth tax assumes a leading position in the vast majority of German texts. This signifies, again, the strong opposition to wealth and inheritance taxation in the German‐speaking countries. By contrast, income taxation is referred to only half as frequently.

In regard to arguments in favor of Piketty's proposals, the (global) wealth tax is equally given priority, but referred to more often in English articles. Inheritance taxation, in contrast, is exclusively picked up in the German articles and remains (almost) unmentioned in the English ones, while property taxation, on the other hand, is an Ireland‐specific debate. Again, income taxation, with very few exceptions, assumes the status of a non‐topic.

Whereas the specific national contexts of political and economic debates cannot be captured fully in this article, we want to highlight a few contemporary national policy debates during our research time period to contextualize the above. While the inheritance and gift tax was abolishedFootnote15 in Austria in 2008 (Korom Citation2017), there was some political discussion for a reintroduction in the relevant period. In Germany, we are confronted with a different situation: inheritance taxation does exist, but is, in fact, very low due to high amounts exempt from taxation for close relatives and corporate property (Korom Citation2017; Bach and Thiemann, Citation2016). The high amounts exempt from taxation for the bequest of corporate property was ruled unlawful by the German Constitutional Court in December 2014, a cause for contentious debates. Given the fact that both Austria and Germany range among the nations with the highest wealth concentrations, it is no wonder that wealth taxation has become part of public discourse, surprisingly though, it is presented as more of a threat than an option. In Austria, the debate on a wage tax reform was going on at the time (finally implemented in 2016), but a connection between Piketty's tax proposals for high incomes and an imminent wage tax reform was not made at all. A similar discussion was taking place in Ireland for a property tax, and the debate is present in the Irish media, albeit in the very few articles that deal with policies. For the UK, it seems puzzling that inheritance taxation is not picked up in any of the corpus articles, given the specific national context. Even though the UK taxes inheritance at a comparatively high rate, it grants large exemptions for close family members and, as a result, it raises very little revenue and applies to very few households (Atkinson Citation2015).Footnote16 Considering the example of the low corporate taxes in Ireland—a cause of major controversy both in Ireland and Europe—the absence of this topic in discussions on inequality (and public policy) has to be labelled a significant silence.

Table 3. Number of Newspaper Articles by Stance Towards Redistribution Policies

In the following section, we discuss the main argumentation strategies based on the three main findings of how redistribution policies are portrayed in our corpus: the discourse on redistribution policies remains superficial, discredits politics and has a distinct opinion on who drives economic prosperity.

The Discourse on Redistribution Policies Remains Distanced

We have identified three argumentative strategies which enable authors to maintain a distanced, superficial stance in the debate on redistribution policies; these are de‐legitimation strategies applied so as not to pursue the issue further. As a preliminary remark, please note that even many of the articles which address inequality as a problem are highly elusive when it comes to policy proposals (e.g., they do not explain or contextualize different forms of taxation).

The first line of argument is grouped into what Eero Vaara (Citation2014) refers to as inevitability: texts proclaim that redistribution policies are no good and not feasible, without any further explanation as to why this is the case. Piketty is characterized as a Utopian, his policy proposals are called “dutiful” (“pflichtbewusst”), or simply not a valid option. From a realist perspective, which the authors themselves claim to take, enhanced redistribution policies are definitely not possible. For example, David Priestland (Citation2014) in The Guardian dismissed the introduction of a global wealth tax as “inconceivable” as they “will come to anything in the near future.” Ranking in this category are insistent arguments that any international agreement would be nothing but Utopian.

Second and likewise, prejudices are introduced as soon as the subject of redistribution policies is addressed. Here, authors exert long‐standing narratives and imaginaries in order to side‐line the debate over possible policies. That “high‐tax policy” will “impoverish societies” (Novak Citation2014) might serve as an example, as well as the idea that only enterprises stir innovation. Another striking example was found in German articles: Piketty's policy proposals are labelled wrong because they “are French”; his policies are part of the economic and financial policy which France “is contaminated with” (Feld Citation2014). Here a dichotomy is constructed, more precisely a long‐standing image of the enemy (Feindbild) is re‐established, to make clear who is right (us) and who is wrong (them).

A further, third strategy may be termed insinuation. Frequent associations with Marx are construed in two different ways. German language articles present Piketty as the “New Marx” (even though he is highly critical of Marxist thought) and thus within the radical left of the political spectrum. Articles in English refer more specifically to the book C21 and its proposals which are referred to as “Marxian,” “ideology‐driven,” “confiscatory,” and “socialist Utopia.” Both strategies serve to undermine Piketty's credibility as a scientist and economist (and his work as a credible contribution to economic thought). The difference is that in the German‐language articles, Piketty is immediately disqualified as a person, therefore, his work does not have to be dealt with, whereas in the articles written in English, the pejorative step is taken later, at the policy level.

The Discourse on Redistribution Policies Discredits Politics

In all of the four countries and in all of the newspapers analyzed, predominantly instrumental forms of economic rationalization feature as an extensively applied strategy to de‐legitimatize policies. Discursive strands making use of this strategy are always constructing on some form of causal relationship between the means (higher taxation on wealth and income) and a variety of negative effects (unemployment, low economic growth, etc.). This typically involves the explicit or implicit adaption of economic concepts such as the rational‐choice theory (and neoclassical economics more broadly), often backed by quotes from experts. These classify redistribution policies as market distortions, as inefficient and entailing high costs for the economy and businesses. In order to lend more force to a rational argument, taxes are treated as personified agents (“taxes kill”) in active clauses, and a large array of metaphors are adduced to mark the immediate danger that emanates from them: taxes are a “burden” that squeeze citizens dry, “cause pain,” “endanger life,” are a “curse,” and are sometimes placed in military, war‐like semantic contexts. Further, Piketty's “recipes” and “prescriptions” are often qualified in semantically negative ways, such as “old” and “narrow‐minded,” and are contrasted with other experts’ proposals described as “innovative,” “creative,” “simpler,” and “more realistic.” Furthermore, there is a strong tendency to present various social and economic actors as victims of state action. Companies and “the entrepreneur” are depicted as the victims of those policies, lacking agency in the face of an aggressive, overpowering, and abusive state that subjects them to the risks of capital flight and bankruptcy.

While opponents of redistribution policies argue with negative impacts on growth and incentives, positive arguments mention the enhancing of stability, raising state revenues, boosting demand, and restoring the meritocratic principle. But even in pro‐redistribution articles, we find a lot of neoliberal framing (“taxes confiscate,” “need to be simplified”) and little positive framing in the Keynesian sense. The latter argumentation is that state action to counteract market developments is necessary and useful (Keynesian), and a market correction is required to check the concentration of wealth. Still, as already stated, the articles with a positive stance towards redistribution policies are fewer and their argumentation more defensive: Policies are portrayed in an ambivalent way, highlighting both their positive as well as negative implications, albeit attesting more weight to the positive ones. Tax avoidance is mentioned and taxes are depicted as a “last resort,” “evoking class conflict” (the latter only in UK articles). Adjectives that semantically feed the opposite discourse, for example “kräftig besteuern” (to tax heavily), “der Staat kassiert” (the state seizes), evoking an image of pushing it too far. Likewise, higher taxation, even though assessed as positive, is frequently characterized as unrealistic.

The overall corpus of newspaper articles also ascribe a highly ambivalent role to the state. On the one hand, the state attributed with the capability to correct and mitigate inequality, contributing to a more equal society (e.g., Nat O’Connor Citation2014). On the other, a clearly neoclassic, neoliberal, and sometimes even Hayekian state (“the road to serfdom”) is presented as “grossly inefficient,” “dysfunctional,” and state power as “abusive,” with the “real problem” being debt, not inequality. The argument against redistribution policies is that less, not more, state intervention is required, sometimes explicitly naming privatization and private pension systems as necessities. The political sphere is entirely absent from the discussion when economic inequality is fundamentally assumed to be the outcome of mechanically interlinked (macro‐)economic processes (as technological change, globalization or simply structural change). Those articles ascribe importance to the inequality problem without depicting any leverage points for political interference at all (e.g.. Harding Citation2014).

When politicians are mentioned as a group, the attributions are either negative (they “use up the additional money,” “nothing will go to the poor”) or attributed to what economists call new political economy (or public choice). Statements like politicians “would not be so foolish to do 80% tax rates,” imply that they only act in the interest of their re‐election and assume that all citizens are against higher taxation. Another version of an “active,” but inefficient political sphere is depicted by Gerald John (Citation2014). Here, politicians are labelled as incapable of taking appropriate action against rising inequality, as they only engage in debating the issues rather than contributing to an effective solution: “Die Regierungsspitzen hauten sich die Studien der Experten um die Ohren, als säßen sie im Volkswirtschaftsseminar.”Footnote17

What Drives Economic Prosperity?

Given this portrayal of redistribution policies and the role of the state, economic prosperity is closely interconnected with entrepreneurialism. The question of “What drives economic prosperity?” is often answered accordingly. The state reduces prosperity, while incentives and entrepreneurs drive it. Ordinary employees are not even mentioned, and politicians exclusively succeed in getting everything wrong. International agreements won't function, and even ordinary people just don't want (higher) taxes.

When companies are qualified, usually a certain type of firm is envisaged: a small or medium‐sized (family) enterprise. Accordingly, wealth and capital are presented as both productive and tied up in the business, and therefore, higher wealth taxes would seriously harm them. This is especially pronounced in the German newspaper articles, where small‐scale family businesses were depicted as the backbone of the German economy, conveniently over‐looking that “many German family firms have outgrown every traditional measure of medium size in past decades while remaining under family control” (Lehrer and Schmid Citation2015, 303).

When public policies are referred to or discussed, there is a high concentration on taxes and regulation, not so much on the investing aspects of public policies, such as in schools, kindergartens, hospitals, or infrastructure. We would like to point out again that we analyzed a text corpus with a Piketty connection, and the relevant proposals in his book largely focus on tax policies, especially income, wealth, and inheritance tax. Still, the articles ignore the fact that both the incentives for innovation, as well as the re‐distributional features of today's everyday life (health, general education, etc.) are based on regulation and public policies. These are an active counterpart to the forces of deregulated capitalism. As many scholars have stressed over the last decades (Galbraith Citation1958; Grisold Citation2011; Mazzucato Citation2015), it is exactly this mix of market forces and counteracting forces that provided for a system that manages to stabilize the economy and curb at least some of the rising social imbalances.

These different approaches may be taken to correspond quite closely to different underlying economic theories, assumptions and ideologies. Whereas neoclassical economics, for example, sees the role of the state in providing only a general frame for market economies, (Post‐)Keynesian and other heterodox theories take a (critical) political economy approach, stressing the necessity of state intervention to curb the self‐destroying tendencies of capitalism, without forgetting that state intervention can lead to contrary effects regarding inequality as well.

“Now, What Exactly is the Problem?” Discussion and Conclusion

A recent cover article in The Economist (Citation2018), subtitled “Time to Bring Tax into the 21st Century” argues that our current tax systems are outdated and that especially rents, high capital gains and windfall gains should be taxed higher. In sharp contrast, the corpus analyzed in this article is much more conservative in regard to tax changes, eager to dismiss (Piketty's) proposals for redistribution policies. It seems the respective articles are (overly) cautious not to appear too radical, as soon as public policies are concerned, with the few exceptions to prove the rule.

In an attempt to clarify the underlying reasons, the intentions and the implications, this concluding chapter synthesizes our theoretical considerations with the empirical findings. The very way of how people are taught to think about and qualify inequality and redistribution policies refers to Veblen's concept of media as educational system, and to the notion of endogenous preferences.

What are the Main Stances on Economic Inequality Depicted by the Media Coverage?

What characterizes most of the texts, no matter where they originated, is the reference to the principle of meritocracy. According to Van Dijk (2004), we label it the “prevalent moral order”, an idealized conception of meritocracy. The appeal to individual merit and hard work tends to play down structural elements of society. Even when it is explicitly conceded that social status is determined by inheritance and birth instead of effort and talent, a solid majority of contributions insinuates that presumed meritocracy was—and still is—a normative principle that worked in the past and should work now as well.

Given the widespread dominance of meritocracy in the countries analyzed, in‐depth analyses of the development of meritocracy and its dominance in public discourse are provided for example by Joe Littler (Citation2018) for the UK and Kai Dröge, Kira Marrs, and Wolfgang Menz (2008) for Germany. While a more detailed examination of why meritocracy is such a persistent explanation of success would require a subsequent contribution, the findings of this study substantiates that the media coverage reinforces already existing societal norms of the advantages of meritocracy. Reconsidering the work of Bowles et al. (Citation2017) that capitalist institutions support the norms and ideologies of capitalism, media as “pecuniary businesses” (as Veblen verbalized it) support a specific form of neoliberal capitalism based on the beliefs of the superiority of individualism.

The economic consequences of inequality on growth (or on economic development) draw on the main controversies in the texts analyzed. The causalities given between growth and inequality are interpreted in contradictory and dichotomous ways, depending on whether inequality is considered a problem or not. The cause‐and‐effect relation is presented as diametrically opposed by the different lines of argument, while the risk that the legitimation of democratic structures might deteriorate further is only addressed if inequality is viewed as problematic.

Although we cannot ultimately determine which target group journalists primarily write for—their advertisers, their supposed readership, or the owners of the papers—we can go back to Veblen's argument that “the trend of its [the media's] teaching, therefore, is, on the whole, conservative and conciliatory” (Veblen Citation1904, 131). Both of these aspects are clearly identifiable in our empirical analysis; hence a clash of interests remains largely undebated, be it between different groups or even classes in society. Any critical political economy approach has to acknowledge that political and economic outcomes are to a large degree subject to different interests within a specific society, and therefore, depend on the contested claims and societal negotiations between those groups—and this inevitably influences wealth and income inequality. Yet, our analysis of media coverage indicates that such a perspective is largely absent. By way of example, inequality is defined and represented as either the result of automated processes (such as globalization and technological change, in which societal actors cannot intervene) or as caused by the inappropriate conditions and rules defined by policymakers. Given that both those processes are, in fact, to a large extent the result of societal negotiations, power imbalances, and divergent interests, we are confronted with a story totally untold—even in those articles that view inequality as a severe problem in our present societies. Largely missing in this panorama is also the interconnectedness of the political and economic spheres. The role of wealthy people in the creation of rules and regulations, which consequently leads to a further increase in wealth and income, is just another significant silence in all but the very few articles. This relative absence of power as an analytical category corresponds to the dominant strands of the academic economic discipline these days, and stands in stark opposition to critical political economy perspectives.

How does Media Coverage Portray and Judge Potential Redistribution Policies?

In our corpus, redistribution policies are addressed to a lesser extent than inequality topics, and are also characterized by a less positive stance, as illustrated by this quote judging Piketty's book: “Admiring the analysis is one thing; accepting the policy prescriptions quite another” (Elliott Citation2014, 11). If articles are hostile towards public policies—and they often are—resentment and prejudice prevail over detailed investigation and discussion. A plausible explanation focuses on what Ngai‐Ling Sum and Bob Jessop (Citation2013) term selectivity. As soon as powerful interests are at stake, we encounter a marked increase in disapproval. Only those articles arguing along Keynesian (or even more heterodox) lines tend to envisage or consider any positive or progressive role for the state. Overall, the policy debates on redistribution stay mostly on the surface. Overall, we can conclude that in the articles analyzed we can identify more significant and forceful statements on inequality than on a coverage of policy proposals, options and alternatives. So it may come as no surprise that people are overly hostile to public policies, especially those regarding redistribution, and especially taxation. While the media's function as a source of information and watchdog can thus thoroughly be questioned, we have to ask what this means for the teaching function of media coverage regarding inequality. We are confronted with rather one‐sided images and concepts: an overemphasis of meritocracy, strong discord over the economic consequences of inequality, an underestimation of the interconnectedness of political and economic spheres, and a neglect of societal negotiations, power imbalances as well as the different interests in society. The very conclusion on (further) redistribution policies is that they are mostly understood in terms of taxation, are discussed and explained to a lesser extent than the general conviction that “something needs to be done,” and are generally given highly negative attributions.

Throughout the corpus, numerous examples of significant silences (Huckin Citation2002) are detected. As already discussed, this not only includes the absence of mentioning power relations, but also a lack of acknowledgment that both the initializing of innovation as well as the re‐distributional features in modern societies (healthcare, general education, etc.) are based on regulation and public policies. They provide, as Galbraith phrased it, an active countervailing power to the forces of deregulated capitalism. As stressed by a considerable number of scholars during the past decades, it is exactly this mix of market and market counteracting forces that provided for a system that manages to stabilize the economy and curb at least some of the most damaging social imbalances. Furthermore, the defensive articles that debate the issue within a historical perspective show a crude and rather naïve faith in markets, totally ignoring the fact that the improvements for the non‐wealthy over time were achieved by class struggles and (sometimes even militant) clashes of interest.

The findings of this research identify a number of conceptual problems in the media coverage analyzed. The arguments highlighted constitute a type of endogenous preferences, thus beliefs, that may be referred to as biased simplifications: (1) an implicit justification and rationalization of the (neo)liberal economic approach to the principles of individual work and merit, and of the centrality of the entrepreneur, (2) very restrained arguments regarding the positive role of public policies for economic development, stability and the welfare state, and (3) a stark (though not total) opposition to new ideas for redistribution policies to counteract inequality. If we want policies against growing inequality to be discussed and implemented, we have to acknowledge that the media information thereof will have to be changed to make this possible. So far, it is not, leaving people with the undebated question of: “Now, what exactly is the problem?”

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Grisold

Andrea Grisold and Hendrik Theine are at the Institute for Heterodox Economics, WU‐Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria. This work is supported by funds of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank, Anniversary Fund, project number: 16789).

Hendrik Theine

Andrea Grisold and Hendrik Theine are at the Institute for Heterodox Economics, WU‐Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria. This work is supported by funds of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank, Anniversary Fund, project number: 16789).

Notes

1 In this article, we use the term “economic inequality” for income and wealth inequality. The term “redistribution policies” is used to describe those policies which aim to reduce economic inequality.

2 For further publications regarding the findings of this project see: Grisold and Theine Citation2017; Grisold and Grabner Citation2018; Grisold and Silke Citation2019; Rieder and Theine Citation2019; Theine and Rieder 2019.

3 The four countries have distinct institutional settings, but share certain characteristics regrading economic inequality. In all countries, economics inequality increased unequivocally with respect to income and wealth. The falling wage share and an increase of capital returns is another shared characteristic. This hints at global forces which tend to drive the movement of inequalities across countries and the blurring of national boundaries (Galbraith Citation2019; Scherrer and Schützhofer Citation2016).

4 CDA (Critical Discourse Analysis) is an interdisciplinary approach to empirically study the construction of social reality diffused (e.g., via the media). Its main aim is to link language patterns with societal and cultural patterns, and with change. As such, CDA focuses not only on textual analysis but views texts and their production as well as reception as embedded in social processes and structures. The central term “discourse” is defined as “construing aspects of the world (physical, social, or mental), which can generally be identified with different positions or perspectives of different groups of social actors” (Fairclough Citation2013, 179). Discourse refers to spoken or written “language use” but can also be extended to other types of semiotic activity (e.g., visual images and non‐verbal communication). The reference to “language” signals the linguistic origins of CDA, which stress that any analysis needs to pay attention to specific linguistic features of a discourse. The reference to “use” highlights the roots of CDA in social theory, ascertaining that language is always in relationship with (and not independent of) society. Language is formed by its social context but also adds to the shaping of this context (Fairclough Citation1995).

5 For those interested in the ownership structures of our corpus newspapers, the respective information is provided in the Appendix.

6 The exclusive use of “Piketty” as our only search term was a methodological necessity, as it would be impossible to conduct a full qualitative CDA of all articles dealing with inequality in all its forms.

7 As a recent phenomenon, the huge debate stirred up by Trump's notion of “fake news” must be mentioned here, albeit with the knowledge that there are many nuances to (mis‐)information (a fact Lippman already paid close attention to in his seminal work of 1923, for example).

8 The dominant mass media of his time.

9 Today's examples show a wider range of media dependence on ad‐sells than in Veblenian times: while commercial TV and a considerable share of the new online media are solely (or predominantly) reliant on advertising as a revenue source, print media is usually both reader‐ and advertising‐financed, as are most of the Public Service Broadcasting stations in Europe and Public Broadcasting Service stations in the United States (Grisold Citation2004; Kiefer Citation2005; Albarran Citation2016; Grisold and Grabner Citation2018).

10 The press has to be slightly more conservative than its reader, is Veblen's argument, because less conservative people are more tolerant, whereas conservative ones have a stricter view of what is right, they are “readier … in their rejection of whatever does not fully conform to their habits of thought” (Veblen Citation1904, 130).

11 In the empirical part, all very short citations in double quotes are taken from our empirical corpus. For the cause of readability, we refrain from citing all those.

12 “Geburt ist Glückssache und keine Leistung.”

13 “ … that a certain, considerable dose of inequality is economically healthy. The prospect of getting rich is urging people to work hard.”

14 “Gucken die Internetprofiteure online eine kostenlose Harvard‐Vorlesung oder daddeln sie mit neuen Spielen herum?”

15 Specifically: suspended by the Austrian Constitutional Court.

16 The exemptions for close family members were extended even further in 2017 (Wilson Citation2018).

17 “The top government throws around expert studies in hot debates, as if just taking part in a course on economic theory.”

References

- Albarran, Alan. 2016. The Media Economy. New York: Routledge.

- Antonelli, Gilberto, and Boike Rehbein. 2018. Inequality in Economics and Sociology: New Perspectives. Oxon: Routledge.

- Atkinson, Anthony. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bach, Stefan, and Andreas Thiemann. 2016. “Hohe Erbschaftswelle, Niedriges Erbschaftsaufkommen.” DIW Wochenbericht 3: 63–71.

- Bagdikian, Ben Haig. 2004. The New Media Monopoly. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Bank, Julian. 2016. “Leerstelle in der wirtschaftspolitischen Debatte? Die Piketty‐Rezeption und Vermögensungleichheit in Deutschland.” Ethik und Gesellschaft 1: 1‐31.

- Bell, Carole V., and Robert M. Entman. 2011. “The Media's Role in America's Exceptional Politics of Inequality: Framing the Bush Tax Cuts of 2001 and 2003.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 (4): 548–572.

- Bernau, Patrick. 2014. “Geld Bringt Weniger: Reichtum war noch nie so nutzlos.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 21, 2014.

- Bettig, Ronald V., and Jeanne Lynn Hall. 2012. Bid Media, Big Money: Cultural Texts and Political Economics, 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

- Birkinbine, Benjamin J., Rodrigo Gómez, and Janet Wasko, eds. 2017. Global Media Giants. New York and London: Routledge.

- Bowles, Samuel. 1988. “Endogenous Preferences: The Cultural Consequences of Markets and Other Economic Institutions.” Journal of Economic Literature 36 (1): 75–111.

- Bowles, Samuel, Richard Edwards, Frank Roosevelt, and Mehrene Larudee. 2017. Understanding Capitalism: Competition, Command, and Change (4th Edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bowles, Samuel, and Yongjin Park. 2005. “Emulation, Inequality, and Work Hours: Was Thorsten Veblen Right?” The Economic Journal 115 (507): F397–F412.

- Bowles, Samuel, and Sandra Polania‐Reyes. 2012. “Economic Incentives and Social Preferences: Substitutes or Complements?” Journal of Economic Literature 50 (2): 368–425.

- Bureau van Dijk. Orbis. 2017. Available at https://orbis.bvdinfo.com/. Accessed November 10, 2017.

- Champlin, Dell P., and Janet Knoedler. 2002. “Operating in the Public Interest or in Pursuit of Private Profits? News in the Age of Media Consolidation.” Journal of Economic Issues 36 (2): 459–468.

- Champlin, Dell P., and Janet T. Knoedler. “American Prosperity and the ‘Race to the Bottom’: Why Won't the Media Ask the Right Questions?” Journal of Economic Issues 42 (1): 133–151.

- Dröge, Kai, Kira Marrs, Wolfgang Menz, eds. 2008. Rückkehr der Leistungsfrage: Leistung in Arbeit, Unternehmen und Gesellschaft. Berlin: Edition sigma.

- The Economist. 2018. “Stuck In the Past: Countries Must Overhaul Their Tax Systems to Make Them Fit for the 21st Century.” The Economist, August 11, 2018.

- Eley, Jay. 2014. “Growing More Relaxed About the Filthy Rich.” Financial Times, April 26.

- Elliott, Larry. 2014. “Thomas Piketty: The French Economist Changing the Way We Think About Wealth” The Guardian, May 3, 2014.

- Fairclough, Norman. 1995. Media Discourse. New York: E. Arnold.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. “Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 7, no. 2: 177–197.

- Feld, Lars P. 2014. Lars Feld: Hauptsache, Mehr Staat: Das Fatale Französische Rezept. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, May 15, 2014.

- Ferschli, Benjamin, Daniel Grabner, and Hendrik Theine. 2019. Zur Politischen Ökonomie der Medien in Deutschland: Eine Analyse der Konzentrationstendenzen und Besitzverhältnisse. ISW‐Report Nr. 118, München: Institut für Sozial‐Ökologische Wirtschaftsforschung.

- Financial Times. 2014. “Big Questions Hang Over Piketty's Work: Data Problems and Errors in Bestseller Must be Addressed.” Financial Times, May 27, 2014.

- Fullbrook, Edward. 2003. The Crisis in Economics. New York and Abingdon (UK): Routledge.

- Galbraith, James K. 2012. Inequality and Instability: A Study of the World Economy Just Before the Great Crisis. Oxford University Press.

- Galbraith, James K. 2014. “Unpacking the First Fundamental Law.” Real‐World Economics Review 69: 145–149.

- Galbraith, James K. 2019. “Sparse, Inconsistent and Unreliable: Tax Records and the World Inequality Report 2018.” Development and Change 50 (2): 329–346.

- Galbraith, John K. 1958. The Affluent Society. Boston, MA: Houghton‐Mifflin.

- Galbraith, John K. 1970a. “Economics as a System of Belief.” The American Economic Review 60 (2): 469–478.

- Galbraith, John K. 1970b. The Anatomy of Power. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Gandy, Oscar H. Jr. 2007. Minding the Gap: Covering Inequality in the NY Times and the Washington Post. Paper presented at the IAMCR Section on Political Communication, Paris.

- Giles, Chris. 2014. “Piketty Did His Sums Wrong in Bestseller that Tapped into the Inequality Zeitgeist.” Financial Times, May 24, 2014.

- Gimpelson, Vladimir, and Daniel Treisman. 2018. “Misperceiving Inequality.” Economics & Politics 30 (1): 27–54.

- Grisold, Andrea. 2004. Kulturindustrie Fernsehen. Zum Wechselverhältnis von Ökonomie und Massenmedien. Wien: Löcker‐Verlag.

- Grisold, Andrea. 2011. “Zwischen Zähmung und Entfaltung. Der regulationstheoretische Ansatz.” In Gesellschaft! Welche Gesellschaft? Nachdenken über eine sich wandelnde Gesellschaft. Edited by Walter Ötsch, Karin Hirte and Jürgen Nordmann, 119–142, Marburg: Metropolis.

- Grisold, Andrea, and Daniel Patrick Grabner. 2018. “Maturity and Decline in Press Markets of Small Countries. The Case of Austria.” Recherche en Communication 44: 49–80.

- Grisold, Andrea, Paschal Preston, eds. 2020. Economic Inequality and News Media: Discourse, Power, and Redistribution. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grisold, Andrea, Paschal Preston, Maria Rieder, Henry Silke, Hendrik Theine. 2017. The Mediation of Economic Inequality. Media Coverage of Piketty's Book ‘Capital in the 21st Century.’ Vienna: Institute for Institutional and Heterodox Economics.

- Grisold, Andrea, and Henry Silke. 2019. “Denying, Downplaying, Debating: Defensive Discourses of Inequality in the Debate on Piketty.” Critical Discourse Studies 16 (3): 264‐281.

- Grisold, Andrea, and Hendrik Theine. 2017. “How Come We Know? The Media Coverage of Economic Inequality.” International Journal of Communication 11: 4265–4284.

- Harding, Robin. 2014. “Incomes Fail to Recover, Except for Those at the Very Top of the Ladder.” Financial Times, October 9, 2014.

- Holt, Jennifer, and Alisa Perren, eds. 2009. Media Industries: History, Theory, and Method. Chichester (UK): Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Huckin, Thomas. 2002. Textual Silence and the Discourse of Homelessness. Discourse & Society 13 (3): 347–372.

- Jäger, Siegfried. 2015. Kritische Diskursanalyse: Eine Einführung, 6th ed. Duisburg: Unrast Verlag.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. 2017. “Mediatizing the “Super‐Rich,” Normalizing Privilege.” Social Semiotics 27 (3): 276–287.

- John, Gerald. 2014. “Kluft zwischen Arm und Reich wächst auch bei uns.” Der Standard, June 5, 2014.

- Kelly, Nathan J., and Peter K. Enns. 2010. “Inequality and the Dynamics of Public Opinion: The Self‐Reinforcing Link Between Economic Inequality and Mass Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (4): 855–870.

- Kiefer, Marie Luise. 2005. Medienökonomik: Einführung in eine ökonomische Theorie der Medien. 2nd ed. München and Wien: R. Oldenburg.

- Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK). 2017. Mediendatenbank. Available at: https://www.kek‐ online.de/medienkonzentration/mediendatenbank/. Accessed November 12, 2017.

- Korom, Philipp. 2017. “Erben [heirs].” In Handbuch Reichtum: Neue Erkenntnisse aus der Ungleichheitsforschung, edited by Nikolaus Dimmel, Julia Hofmann, Martin Schenk and Martin, Schürz, 244–254. Wien: Studienverlag.

- Lehrer, Mark, and Stefan Schmid. 2015. “Germany's Industrial Family Firms: Prospering Islands of Social Capital in a Financialized World?” Competition & Change 19 (4): 301–316.

- Lippmann, Walter. 1923. Public Opinion. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Littler, Joe. 2018. Against Meritocracy. London/New York: Routledge.

- Luhmann, Niklas. 1996. Die Realität der Massenmedien [The Reality of the Mass Media], 2nd ed. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Mazzucato, Mariana. 2015. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. Vol. 1. Anthem Press.

- Mishel, Lawrence, John Schmitt, and Heidi Shierholz 2014. “Wage Inequality: A Story of Policy Choices.” New Labor Forum 23 (3): 26–31.

- Monbiot, George. 2014. “The Rich Want Us to Believe Their Wealth is Good For Us All: As the Justifications for Gross Inequality Collapse, Only the Green Party is Brave Enough to Take on the Billionaires’ Boot Boys” The Guardian, July 30, 2014.

- Noam, Eli. 2016. Who Owns the World´s Media? Media Concentration and Ownership around the World. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Novak, Julie. 2014. The Panel: Thomas Piketty's Capital, The Guardian, May 1, 2014.

- O’Connor, Nat. 2014. “Why Raising Taxes in Ireland Would Be Good For Everybody.” Irish Independent, June 20, 2014.

- Ortner, Christian. 2014. “Wäre Österreich denn besser dran, wenn es keine Milliardäre gäbe?” Die Presse, May 16 2014.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty‐First Century. Oxford: Cambridge University Press.

- Preston, Paschal, and Henry Silke. 2011. “Market ‘Realities’: De‐Coding Neoliberal Ideology and Media Discourses.” Australian Journal of Communications 28 (3): 47–64.