Abstract

In this article we examine how the strategic investment partnership between China and African countries has come to be identified and labeled in the discourse on Sino-African relationships. The emerging narrative is that Chinese investment in Africa is fraught with issues such as labor abuses, risky loans, and imported labor, therefore contributing little to employment generation and local skills development. Nevertheless, we identify good Chinese-financed business outcomes, suggesting that Chinese investments in Africa have positively impacted technology transfer and significantly bridged Africa’s infrastructure gap; our estimation points to a high workforce localization rate within Chinese firms, of above 80%. In making explicit how these competing perspectives play out in the form Sinophilia and Sinophobia, we induce an integrative framework which assimilates the two perspectives to delineate the affection/disaffection phenomena characterizing the evolving China-Africa business relationship. We also set out an agenda for future research.

China and Africa have been known to share similar historical traditions and common experiences: “history of exploitation by imperialists, victimized through externally-funded civil wars and subjected to calamitous socialist projects in the name of idealism” (Alden Citation2007, 136). In addition, about forty years ago, both China and Africa were labeled as poverty-stricken: stuck in debt, few financial resources, inadequate food for their ever-growing populations. However, while many countries in Africa remain under-developed with few forms of industrialization, the modern China has been successful in achieving a remarkable transition from industrial straggler to industrial leader. For instance, whereas China accounted for only about 4% of global GDP in 2003, it now accounts for about 16%—almost a four-fold increase—surpassing Japan and others to become the second biggest economy in the world (see, for example, Morrison Citation2019). Economic growth in Africa, however, has not been as impressive, albeit economic growth varies sharply across the continent’s fifty-four countries. In 2016, for example, the continent’s overall growth slumped to 1.4% (IMF Citation2017).

Hence, China is a salutary example of a once impoverished country rising through the developmental ranks to become a now prosperous nation, the growth engine of the world economy, an idea which holds a great fascination for most African governments (Lekorwe et al. Citation2016). It hardly comes as a surprise, then, that in merely two decades China has become a very significant stakeholder in the economic activities of many African countries (Sun, Jayaram, and Kassiri Citation2017). More significantly, many African countries continue to benefit from Chinese-funded, large-scale infrastructure projects which can kick-start industrialization and boost their economies (Foster et al. Citation2009). Additionally Chinese investments in human capital development/employment generation (Sautman and Yan Citation2015), skills training, and technological transfer (Brautigam Citation2009) have been promising.

Notwithstanding these positive economic developments, the discourse surrounding Sino-African engagement continues to be filled with ambivalence and ambiguity (Ado and Su Citation2016; Tull Citation2006). While some regard China’s strategic partnership with Africa as having the potential to birth credible development and prosperity (Sautman and Yan Citation2007; Whalley and Weisbrod Citation2012; Yin and Vaschetto Citation2011; Kaplinsky Citation2013) through trade openness (Borojo and Jiang Citation2016) and private entrepreneurship (Gu Citation2009), others see mixed benefits and a potential for threat (Busse, Erdogan, and Mühlen Citation2016; Eisenman and Kurlantzick Citation2006). Some studies have drawn conclusions to the effect that the Chinese presence in Africa has negative consequences on most of the transitional economies on the continent (Chemingui and Bchir Citation2010; Elu and Price Citation2010). More specifically, some analysts have sought to question the Chinese commodity-backed financing schemes.Footnote1 Are these loans a “blessing” or a “dangerous trap”? Has Chinese investment had an impact on Africa’s industrial and infrastructural sector? Do Chinese enterprises in Africa contribute to employment generation by employing the local workforce?

In addressing these questions, we employ a qualitative meta-analysis framework to synthesize the competing perspectives of the literature on Afro-Chinese economic engagements concerning the operations of Chinese firms and investments and their relevance to Africa’s development. Our aim is not to contribute to new theoretical foundations due to the wealth of accumulated knowledge on Afro-Chinese business relationships. Rather, we bring together relevant but scattered evidence of the positive impacts (Sinophilia)Footnote2 and the negative impacts (Sinophobia)Footnote3 of the operations of Chinese firms and investments in Africa, in order to extend our understanding of the emerging academic tribes and territories shaping the evolving Afro-Chinese business relationships’ landscape. Overall, we find that deep concerns about the operations of Chinese businesses and investments remain risky loan deals and labor abuse. However, we find contrary evidence to the alarmist perception of Chinese mass importation of labor into Africa’s labor markets. The evidence from empirical works points to a workforce localization rate of above 80% for large and medium-scale Chinese enterprises. In addition, we find favorable Chinese-financed investment outcomes in most African economies: infrastructure development, skills development, and technology transfer. We argue that these developments have constitutively culminated into what we describe as an “affection/disaffection phenomenon,” characterizing the evolving China–Africa business relationship. The rest of our article is organized in three main sections: following the introduction, which captures a brief general overview of the “China in Africa” discourse, we delineate the Sinophilia-Sinophobia arguments characterizing the Afro-Chinese engagement. Finally, we offer our concluding thoughts and suggest avenues for future research.

Sinophilia: The Context

“If the Chinese had colonised us, we would be more developed” (Anonymous interviewee in Burkina Faso) (Khan Mohammad Citation2014, 87).

As earlier indicated, the Chinese presence in Africa holds a great fascination for most African nationals, academics, and commentators (Lekorwe et al. Citation2016; O’Brien Citation2016). Their achievements in technological and infrastructure advancements are a matrix by which African states and entrepreneurs can be measured. The Chinese economic reforms which have catapulted a once agrarian economy into one of the world’s largest industrial economies are inspiring and remarkable. Many Africans and scholars therefore see the Chinese socio-economic and infrastructure development model as a blueprint that can be duplicated or borrowed in order to unlock the huge developmental potential of many African economies (Johnston and Earley Citation2018).

From the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 until the modern times, Chinese foreign politico-economic policy instruments have been far more aligned to the needs and interests of African governments (Anshan Citation2007; Campbell Citation2008); their past diplomatic records, devoid of colonialism and imperialism, have left no negative records on African states (Alden 2007). In the 1960s China’s anti-colonial ideals and Marxist belief that independent states are obliged to help colonized states to achieve and defend their national independence, actually led to increased Chinese activism on the African continent (Alden and Alves Citation2008). Anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements in Africa greatly benefited from Chinese support. Indeed, China provided monetary and technical support to several African countries in the heady days of the independence struggle, with countries such as Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Angola, and Ghana being beneficiaries of such support (Alden and Alves Citation2008; Gao Citation1984; Yu Citation1977). This financial support, post-colonially, has transformed into substantial resource-backed loans and grants to help finance much-needed infrastructure projects in many African states. Especially welcome is the fact that the Chinese loans, interwoven with aid and trade, are relatively cheap and easily accessible with few or no conditions, which represents a major shift from the “strings-attached” financing policies of Western donors and the structural adjustment programs (SAPs) that were inimical to most African economies in the 1980s (Tan-Mullins, Mohan, and Power Citation2010). This is “China’s ‘exceptionalism’” (Alden and Large Citation2011). An exceptionalism pillared on the foreign policy framework and principle of non-interference in internal affairs—”the Beijing consensus” (Ramo Citation2004)—and underpinned by the belief that the best way to minimize conflict and instability is to improve economic development. In summary, African leaders’ affection for China has increased substantially over the last few decades due to China’s long-established, non-colonial diplomatic partnership and, more recently, its decision to provide soft loans and invest in building infrastructure in Africa. We now turn our attention to the significant role and patterns of Chinese-African engagement in order to unpack what is driving Africa’s new affection for China.

The “Flying Chinese Geese”

Chinese companies have become the most ardent investors in Africa (Alden and Davies Citation2006; Brautigam, Weis, and Tang Citation2018). The diversity of Chinese companies is considerable, ranging from major multi-million dollar state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to small and medium-sized enterprises or businesses run by individuals (Alden and Davies Citation2006; Alden, Large, and Soares de Oliveira Citation2008; Kaplinsky and Morris Citation2009; McNamee et al. Citation2012). Although the majority of Chinese companies in the initial phase of market entry had been SOEs, a groundswell of entry by private Chinese companies into the African entrepreneurial arena has been observed in recent years (Alden, Large, and Soares de Oliveira Citation2008; Brautigam, Tang, and Xia Citation2018; Shen Citation2013). These Chinese investors, including large firms seeking new locations for production as part of global networks and value chains, together with their entrepreneurial networks, appear to have been substantially integrated into the African business community with more embedded positions built up over the years (Alden, Large, and Soares de Oliveira Citation2008; Brautigam, Tang, and Xia Citation2018). Considering these developments, a strand of literature has explored whether the China-Africa partnership (related to capital and manufacturing investment and industrialization patterns) fits the “flying geese” model documented by Kaname Akamatsu in 1962.

Formulating a historical theory based upon a study of the economic development of Japan, Akamatsu (Citation1962) employs the term “wild-geese-flying” pattern of industrialization to denote development occurring after a less-advanced country enters into an international economic relationship with an advanced country. The metaphor of a flock of flying geese is used to illustrate the mutual interactions between advanced economies and less-developed economies. Thus in the 1950s Western European countries (considered the “leading geese” in the production of industrial goods) moved towards higher stages of capital and knowledge-intensive development and came to rely on Asian countries (considered the “follower geese”) to take on labor-intensive factory production. Within Asia, Japan became the earliest industrializer, its companies being able to adapt to high-technology manufacturing sectors, taking over the “leading goose” position, while China and other Asian countries became “follower geese” taking on the basic manufacturing role. Of importance to this study, Akamatsu further explains that during the intermingling between advanced and less-developed economies, capital and techniques infiltrate the less-developed economies, leading to the production of goods and consequently necessitating the development of infrastructure.

Using this theory as a backdrop, numerous studies have sought evidence for whether the presence of Chinese entrepreneurs and investments has served to catalyze and ignite industrialization and manufacturing in African countries. Is there empirical evidence that Chinese firms are transferring technology and diffusing skills in Africa, just as Japanese and Western firms did when they intermingled with Asian and other economies? Are Chinese manufacturers the “leading dragons”(Lin Citation2011)? Works by the prominent Afro-Chinese scholar, Deborah Brautigam, have done much to inform the global debate on the positive outcomes of Chinese investments and their consequences for the African industrial landscape. Over the years her works have been exemplary in demonstrating the linkages between Chinese investment and industrialization in many African countries. In an illustrative case of Chinese “geese” (investors) catalyzing processes of industrialization in Africa, Brautigam (Citation2003) finds Chinese entrepreneurs to have facilitated an export-oriented manufacturing growth in Mauritius and to have helped in the creation of an industrial boom in spare parts production in the eastern Nigerian town of Nnewi. In her seminal work The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa, Brautigam finds Chinese investments in manufacturing ventures in numerous African countries including Ghana, Nigeria, and Tanzania to have provided employment opportunities in local communities, enhanced technology transfer, and boosted human capacity development. The findings are consistent with that of Brautigam, Tang, and Xia (Citation2018) who observe four kinds of Chinese “geese” seeking strategic investment opportunities in Africa and each presenting different kinds of development opportunities for structural transformation in the African industrial sector. These “geese” include large firms seeking new locations for production as part of global networks and value chains, large strategic local-market seeking “geese,” raw material-seeking “geese,” and small “geese” travelling together in flocks. Similarly, yet more explicitly, conclusions can be drawn from another study which finds that C&H Garments, a Chinese clothing company, has been very instrumental in contributing to the processes of technology transfer between Chinese and local entrepreneurs and to the catalysis of structural transformation in the Rwandan garment industry (Eom Citation2018).

Other research works have also acknowledged how Chinese investment linkages are increasingly becoming an essential component of Africa’s industrial dynamism. Within this domain of works, Liu Haifang and Jamie Monson (2011) trace the beneficial consequences of the “technical co-operation” and technology transfer trajectories, which had existed between the Chinese railway experts and African workers engaged in the construction and maintenance of the Tazara Railway. Chinese investments in Tanzania, it is observed, have created backward and forward linkages with the local economy (Xia Citation2019b and Xia Citation2019a). A study into Chinese linkages in Ethiopia’s leather industry by Deborah Brautigam, Toni Weis, and Xiaoyang Tang (2018) reveals that the Ethiopian government has nurtured a booming leather industry by attracting prominent Chinese investments. Xiaoyang Tang (Citation2019b) reveals that Chinese investment has positively impacted skills development and technology transfer in the cotton sector in Zambia and Malawi. Yunnan Chen et al. (Citation2016) find some limited but significant cases of technology transfer through technical partnerships between Chinese and Nigerian entrepreneurs in the Nigerian automobile assembly and light manufacturing industries. Elsewhere, Irene Sun and Qi Lin (Citation2017) highlight how AVIC International, a Chinese state-owned company, has made telling contributions in skills development programs in Kenya. China Road and Bridge Corporation also offered technology transfer training programs during the construction of the Standard Gauge Railway project in Kenya (Morangi Citation2015; Wissenbach and Wang Citation2017).

The skills training programs and centers of Huawei Africa have received extensive coverage by Benjamin Tsui (Citation2016). Other studies have, however, complemented it. Specifically in Nigeria, Motolani Agbebi (Citation2019) reveals that Chinese-owned Huawei Technologies has made a significant contribution to training and skill development in the telecom sector via multiple routes: internal employee training activities, training for clients and partners and other training programs in partnership with the Nigerian government. The study also reveals that the Huawei training center in Abuja, which serves employees from Nigeria and other West African countries, has trained over 50,000 people. Similarly, Kenneth King (Citation2010) reports that Chinese-owned Huawei Technologies in Kenya operates a regional training center in Nairobi, providing training to the clients who buy their systems, with the training mainly led by Kenyan engineers for other Africans in their client firms; see King (Citation2011) for similar Chinese-sponsored human development programs in Ethiopia. Not only do Chinese enterprises and multi-national companies (MNCs) directly effectuate technology transfer and skills development in the industrial sector in Africa (Rui, Zhang, and Shipman Citation2016), but they also have significant effects on the labor sector in terms of employment generation, which indirectly translates into a considerable diffusion of skills learned on the job and the introduction of factory culture (Brautigam, Tang, and Xia Citation2018), a discussion to which we turn our attention later.

Employment Creation

Dominant narratives, usually disseminated by the media, maintain that Chinese companies contribute little to employment generation in Africa. Robert Rotberg (Citation2015) states: “What China rarely does, however, is transfer technology to locals. Nor does it routinely employ African middle managers or even foremen. Sometimes it even imports masses of pick and shovel laborers direct from China to work on the roads or down the mines.”

However, the empirical evidence points to significantly high rates of labor localization by Chinese companies in Africa. In we present a summary of Chinese companies’ employment generation in Africa. Following this is , which shows their labor localization rate for investments in Africa (cluster of firms).

Table 1. Compilation of Data on Localization Rate of Labor on Chinese Investments in Africa

Table 2. Compilation of Data on Localization Rate of Labor on Chinese Investments in Africa (Cluster of Firms)

Considering the evidence from the tables, our estimation is that large- and medium-scale Chinese companies—those with an average workforce of not less than 100—have a labor localization rate of above 80% in Africa (see also, Ofosu and Sarpong Citation2021). However, the Chinese government, private Chinese companies, and individual entrepreneurs in Africa exhibit different employment generation patterns as demonstrated by Xiaoyang Tang (Citation2010). According to the study, there are two major patterns in Chinese companies regarding local employment. The first is the “bulldozer” pattern of employment, where a large phalanx of Chinese labor is shipped to Africa to undertake a project or to be employed in Chinese firms. The second is the “locomotive” pattern, where Chinese companies seek to establish close links between Chinese and local people to integrate the Chinese company into the local industrial space. The companies usually pursue long-term profits by establishing synergic growth together with Africans. Employing factors such as capital and technology, this locomotive model usually contributes to large scale local development including training, direct and indirect employment, as exemplified in the above section on the “flying geese.”

According to Xiaoyang Tang (Citation2010) the bulldozer pattern is usually manifested in public projects sponsored by government agreements, where the enterprises are mostly concerned with keeping schedules, because this is also the biggest interest of the politicians who award the contracts. These projects are usually one-time and short-term (less than three years). Such situations are usually manifested in post-conflict countries and are advantageous to these countries because of the chronic lack of qualified personnel to undertake vast reconstruction, which necessitates the mass importation of foreign labor to speed up infrastructure construction in order to improve living conditions and provide a solid basis for further development. However, even in such situations as the post-conflict era in Angola, the ratio of Chinese employees did not exceed 40% (X. Tang Citation2010). Moreover, the ratio of Chinese employees attached to projects sharply reduces as Chinese companies grow and projects get completed. Accordingly, in many manufacturing and mining enterprises in Angola, 60–70% of the initial Chinese employees returned home after the projects had been completed and operations had begun (X. Tang Citation2010).

The operations of the private Chinese companies and individual entrepreneurs demonstrate the locomotive model where Chinese capital and “geese” infiltrate the labor market to create synergies with local Africans, creating direct and indirect employment opportunities. These companies, entering the market in line with the logic of globalization and profit maximization, do not usually engage in the bulldozer pattern, because it is economically unwise for them to do so—as expressed by a project manager of a Chinese construction firm: “bringing workers from China can easily cost up to 10 times as high as hiring workers locally. Expatriate and repatriation compensation and benefits are now too expensive” (Meng and Nyantakyi Citation2019, 8).

Furthermore, Xiaoyang Tang (Citation2010) demonstrates that the growth of business usually corresponds with high labor localization; correspondingly, the localization of management and technical positions also progresses with the growth of the company. Thus, we further estimate that as more Chinese enterprises get integrated into Africa’s industrial sector for long periods, the labor localization rate is likely to increase, with some Chinese companies attaining complete localization in the next decade. This estimation is premised on recent reports that China overtook the United States and the UK as the number one destination for Anglophone African students, with the African student body in China growing 26-fold from just under 2,000 in 2003 to almost 50,000 in 2015 (Breeze and Moore Citation2017). This implies that many young African students have had more recent opportunities to develop knowledge and skills and to learn Mandarin, so as to make them employable in Chinese firms. These Chinese-trained African experts are therefore likely to replace the Chinese “experts” who are deemed expensive to hire. In a related development, however, other studies have shown that the patterns of employment manifest in ways where the skilled and top-level management positions are mainly occupied by Chinese nationals—a situation often considered exploitative. This issue is germane to this study; hence we examine it in a later section. Meanwhile, it is important to note that the sustainable operations of local, Chinese, and non-Chinese firms in Africa depend heavily on the availability of infrastructure. How is Chinese investment helping in this regard? We explore this in the following paragraphs.

Infrastructure

To end poverty, build a road—Chinese proverb (Brautigam Citation2009, 308)

Demand for the expansion of infrastructure amenities soars daily with the ever-increasing population rise in Africa. Africa’s infrastructure deficit is huge and costly (Foster and Briceno-Garmendia Citation2010; Gutman, Amadou, and Chattopadhyay Citation2015). According to Vivien Foster et al. (Citation2009) the limited infrastructure services in Africa tend to be more costly than those available in other continents. For example, road freight costs in Africa are two to four times higher per kilometer than those in the United States, and travel times along important export corridors are two to three times longer than those in Asia; in the power sector, generation capacity and household access in Africa are around half the levels observed in South Asia, and about a third of the levels observed in East Asia and the Pacific (Foster et al. Citation2009). The study further estimates that Africa’s deficient infrastructure may be costing one whole percentage point of per capita GDP growth per year.

Thus, Africa’s infrastructure deficits partly explain the continent’s underdevelopment. Closing the continent’s infrastructure finance gap is therefore important for its prosperity, and this is where China—the largest bilateral infrastructure financier in Africa—becomes relevant. Whereas on the one hand most African countries (well-endowed with natural resources) face massive infrastructure deficits with large investment needs and an associated financial gap; China, on the other hand, has been successful in accumulating substantial financial reserves but lacks much-needed natural resources to fuel its fast-expanding industrial base (Alves Citation2011 and 2013). In addition, China has developed one of the world’s largest and most competitive construction industries with a vast knowledge base in the engineering and construction sectors which is necessary for infrastructure development (C. Chen et al. Citation2007; McDonald, Bosshard, and Brewer Citation2009; C. Chen and Orr Citation2009). This being the case, the needs of China, cash-loaded and in search of mineral resources to power and sustain its domestic industrial growth, have converged with the needs of Africa, blessed with a vast amount of natural resources but lacking the financial wherewithal to provide basic infrastructure amenities for its citizenry (Alves Citation2011). Africa and China complement each other: China gets what it wants—natural resources—and builds and provides what Africa needs—basic infrastructure (Corkin, Burke, and Davies Citation2008; Corkin and Burke Citation2006; Huang and Chen Citation2016) of good quality (Farrell Citation2016); this is in marked contrast to the role of other international lending institutions who have shifted their sphere of concern away from funding infrastructure projects (Brautigam and Hwang Citation2019). It is worthy to note, however, that other studies have shown that China’s investments in Africa’s infrastructure and markets are not limited to China’s quest for natural resources (W. Chen, Dollar, and Tang Citation2016; Yin and Vaschetto Citation2011). Whatever the Chinese interests are, however, their investments in infrastructure development have been promising. The OECD (Citation2012, 50) notes that China’s investment in infrastructure “has helped develop infrastructure in fragile and low-income states, which may otherwise not have had access to market finance or even to donor funding which tends to focus on social sectors in these countries.”

Through aid (Carter Citation2017) and resource-backed concessional loans (whereby the beneficiary government pays for its infrastructure costs through mining or oil extraction rights) the Chinese have aimed to bridge Africa’s infrastructure deficit by financing major infrastructure and hydropower projects throughout the continent. According to Sun, Jayaram, and Kassiri (Citation2017), China’s commitment to infrastructure in Africa in 2015 amounted to US$21 billion—more than the combined total of the Infrastructure Consortium for Africa (whose members include the African Development Bank, the European Commission, the European Investment Bank, the International Finance Corporation, the World Bank, and the Group of Eight (G8) countries). Given the current power supply crisis in AfricaFootnote4 and the fact that the continent has developed barely five percent of its identified hydro potential, the emergence of China as a major financier of hydro schemes is of great strategic importance for the African power sector (Foster et al. Citation2009). Of seventeen major hydropower projects between 2000–2013, estimated to have added 6,771 Megawatts (MW) of power in sub-Saharan Africa with an estimated cost of US$13.3 billion, Chinese finance is estimated to have contributed US$6.7 billion (Brautigam and Hwang Citation2019). In addition to these seventeen projects with an element of Chinese funding commitment, the study further shows that Chinese companies are involved in the construction of six large hydropower projects in Africa funded by non-Chinese financiers (Brautigam and Hwang Citation2019).

Although its construction was mired in human rights and environmental impact concerns, the Merowe Dam has greatly augmented electricity supply to cities and industrial centers in Sudan (Brautigam and Hwang Citation2019; McDonald, Bosshard, and Brewer Citation2009). Other major hydropower projects include the 400MW hydroelectric Bui Dam project in Ghana, which has the ability to operate for up to 100 years, providing irrigation for 30,000 ha of land and supplying 980 Gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity annually (Kirchherr, Disselhoff, and Charles Citation2016; K. Tang and Shen Citation2020) and the Memve’ele hydroelectric dam, which supplies Cameroon’s electric grid with 210MW of electricity (Y. Chen and Landry Citation2016). Dubbed “the mother of all Chinese infrastructure projects in Africa,” the “Tan-Zam” railway line linking Tanzania and Zambia is one of the most notable Chinese-funded projects in Africa (Haifang and Monson Citation2011). Others include Kenya’s largest infrastructure project: the standard gauge railway linking Mombasa and Nairobi (Kuo Citation2017; Wissenbach and Wang Citation2017), Africa’s first transnational railway (756kilometers) linking Addis Ababa and Djibouti (Dahir Citation2018b), the 1344 kilometer Lobito-Luau railway in Angola, the revamping of the Nigerian light railway in Abuja and the $1.2 billion Tanzania Gas Field Development Project (Sun, Jayaram, and Kassiri Citation2017).

Regarding the quality of Chinese infrastructure works in Africa, there have been a few reported cases of poor quality works (cf. for example, Kuo Citation2018). However Jamie Farrell (Citation2016), quantifying the quality of completed World Bank civil engineering projects in the transportation sector between 2000 and 2007, empirically found no statistically significant difference between the quality of work of Chinese firms and OECD country firms. Indeed, where efficiency and cost effectiveness are concerned, other studies have shown that the Chinese construction firms stand out: their experience in delivering low cost infrastructure projects in a quick time frame has been noted. Christopher Burke (Citation2007), in a case study of construction firms in Tanzania and Zambia, states: “Chinese companies are also quickly earning a reputation for good quality and timely work, rendering them popular in both the public and private sectors” (2007, 329). Burke (Citation2007) further identifies that Chinese construction firms have become competitive and have gained advantage over many local and non-Chinese firms due to their good quality low-cost skilled labor, hands-on management style, high degree of organization, general aptitude for hard work and access to relatively cheap capital. Studies also reveal that while local and other foreign construction firms usually operate on profit margins of 15–25%, Chinese companies often operate on margins of under 10%, sometimes (e.g. in Tanzania) as low as 5%, and sometimes even as low as 3% (e.g. in Ethiopia), thereby making them extremely competitive and the most affordable option to many African governments (Burke Citation2007; Corkin et al. Citation2008).

Despite these positive Sino-African engagements however, some analysts have shown that China’s infrastructure-for-resources loans are fraught with significant problems. The credit lines that finance these infrastructure projects often come tied to the procurement of goods and services from China, leaving only a small margin for local content in the recipient country; in addition, China’s providing of the loans has the potential to push some countries into a cycle of debt with consequential negative long term impact on economic stability (Alves Citation2013). We explore this issue in the paragraphs that follow.

Sinophobia

Loans and Debts

As noted earlier, unlike the pre-1990s when China’s foreign policy in Africa was primarily based on politico-ideological or politico-diplomatic favor-procuring considerations, China’s post-1990s foreign policy engagements in Africa have been purely structured around politico-economic considerations (Konings Citation2007) and resource security concerns, with the acquisition of oil and hard natural minerals forming the epicenter of these economic motivations (Alves Citation2011; Wang Citation2012; Taylor Citation2006; Jaffe and Lewis Citation2002). This comes as little surprise given that China’s enormous growth in the manufacturing and technological sectors has necessitated the sourcing of commodities from the outside world (Sanfilippo Citation2010; Jaffe and Lewis Citation2002). Resource security has even become more pertinent in China’s foreign policy framework since the nation’s social stability as well as its regime survival has come to depend on the maintenance of its massive economic growth achieved over the last couple of decades (Alves Citation2011). Within this context, Africa—with its large but little-exploited resources—has caught China’s eye and has thus emerged as a new frontier for Chinese resource acquisition (Jiang Citation2009). Indeed China has also caught the attention of African governments and this can be explained by the fact that many African governments resent the conditions attached to Western donor assistance (Shinn Citation2007). China, however, positions itself as an undemanding investor. Therefore, many African governments, in desperate need of funding opportunities to rehabilitate or construct major infrastructure projects, have embraced Beijing with open arms. Beijing, in turn, has not resisted this warm welcome.

Consequently China has carefully ramped up its official development assistance (ODA) flows to African states in furtherance of its foreign policy interests (Dreher et al. Citation2018) including resource acquisition objectives (Taylor Citation2007). These types of grants and loans in particular, collateralized by strategically important national assets with high long term value and mostly to be repaid in kind, have mainly targeted not only well-known mineral rich countries such as Angola, Sudan, Nigeria, and the DRC but also new oil-producing countries such as Ghana and Uganda (Alves Citation2011). Indeed, many African countries have received millions of dollars of loan facilities from China (Were Citation2018). A recent dataset released by the China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies reveals that between 2000 and 2017 African governments and their SOEs had received loan facilities worth US $143 billion from Chinese government, banks and contractors, Angola being the top recipient with US $42.8 billion (CARI Citation2018).

Herein lies the danger, the Sinophobia engendering deep-seated discontent among some Afro-Chinese analysts. Seeking to interpret the Chinese infrastructure-for-resource loans “black box,” some analysts suggest that the loans are meant to “debt trap” African states, to “resource grab” the extensive mineral riches of Africa. The U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson opines that the Chinese predatory loan practices undermine African regimes and mire them in debt (Kazeem and Dahir Citation2018). A closer look at the debt situation of some African economies lends credence to these assertions: while Chinese loans are less substantial in the debt of some African countries, Chinese loans in Zambia, the DRC, and Djibouti remain the most significant contributor to high risk of or actual debt distress (Eom, Brautigam, and Benabdallah Citation2018). Kenya’s debt to GDP situation makes for grim reading (Sanghi and Johnson Citation2016)and as of March 2018 its debt to GDP ratio had surpassed 62%, with China its largest lender and accounting for 72% of the bilateral debt (Dahir Citation2018a). This raises serious concerns about the debt sustainability management of these African nations. Similar concerns have been raised in oil-rich Angola which owes about half of its external debt to China (Adegoke Citation2018).

Bilateral and external debts are nothing new. All countries, whether rich or poor, are financially indebted to another in some way. It is the structure of the Chinese loan deals with Africa and other debt-strapped countries that is so alarming (Ayittey Citation2017): Chinese loans are sometimes shrouded in secrecy and mostly do not require good governance guarantees (Taylor Citation2007); they are collateralized with important national assets and there always exists the prospect of the Chinese government taking over these assets in case of default by the borrowing country. This is what Brahma Chellaney (Citation2017) refers to as “China’s debt trap diplomacy” and “creditor imperialism.”

Illustrative of the worrying “risky-Chinese-loan deals” phenomenon in Africa is the loan agreement signed between the DRC government and the Chinese SOEs in 2007 (Global Witness Citation2011; Kabemba Citation2016; Marysse and Geenen Citation2009). Examining the specific features of the agreement—the suspensive and resolutive conditions, the barter principle that masks the real price of the commodities, its expansive duration, the exemptions from taxes, etc.—Stefaan Marysse and Sara Geenen (Citation2011) find that even the renegotiated version of the deal represents an unequal exchange, with the Congolese government having been the weaker bargaining party in the contracts. Claude Kabemba (Citation2016) finds the loan agreement to have been negotiated in secrecy. A report by Global Witness confirms that very little information is publicly available on the Sino-Congolese “infrastructure for resource” deal signed in 2007 and further reveals that the deal was negotiated behind closed doors without any prior international bidding process (Global Witness Citation2011).

Labor

As indicated earlier, the increasing Chinese economic presence in Africa has positively impacted African labor, yet while it generates employment opportunities for large numbers of Africans, poor working conditions in Chinese enterprises are of concern to many labor activists (Ofosu and Sarpong Citation2021). Wenran Jiang (Citation2009) considers this a reflection and externalization of China’s domestic labor practices. The numerous complaints of labor rights abuses in Chinese firms and the Chinese disregard for labor union involvement in projects (Isaksson and Kotsadam Citation2018) have led to an increased focus on the labor relations dimensions of Afro-Chinese engagement. Just as the labor problem was central to European colonial domination and post-independence political struggles, it is also the fulcrum of Chinese-business discourses in Africa today. Consider the “casualization” of labor in Zambia and Tanzania (Lee Citation2009), labor rights abuses perpetrated by Chinese companies operating in the mining sector in the Katanga Province of the DRC (Goethals, Okenda, and Mbaya Citation2009) and labor abuses in Chinese copper mines culminating in the death of forty-six Zambian workers following a mine explosion in Chambisi (Human Rights Watch Citation2011). Other studies have also highlighted the Chinese-African labor problem, prominent among them is Chinese Investment in Africa: A Labor Perspective (edited by Anthony Baah and Herbert Jauch Citation2009), which contains ten country case studies showing labor abuses and poor working conditions in Chinese firms.

However, more nuanced accounts of Chinese-African labor relations exist in other studies (Lee Citation2009; Rounds and Huang Citation2017; Mohan Citation2013; Mohan and Lampert Citation2013; Giese Citation2013). Ben Lampert and Giles Mohan (2014) recount that many workers in Ghana and Nigeria who feel negatively affected by the actions of their Chinese employers often emphasize that the Chinese presence is not the sole cause of their problems and do not necessarily engage in “anti-Chinese” agitation. In many instances, other foreign actors or even fellow locals are seen to be equally or even more responsible (Yan and Sautman Citation2013) and general issues of local governance and regulation are consistently highlighted as the most pressing concerns. Indeed, rather than Chinese migrants or foreigners, it is overwhelmingly the state that is the target of resentment (Lampert and Mohan Citation2014). Moreover, not all Chinese bosses are bad employers and not all Chinese firms are “labor abusers.” Evelyn Atomre et al. (Citation2009) reveal that UNTplc (United Nigeria Textile plc, a 100 percent Chinese-owned textile company) was highly-rated in terms of labor practices and had become a “model in the industry” (2009, 352). Many instances of good relations between Chinese employers and African employees also exist (Lampert and Mohan Citation2014). There is no evidence to substantiate claims that Chinese firms employ Chinese prisoners as laborers in Africa (Alden 2007; Brautigam Citation2009; Corkin, Burke, and Davies Citation2008; Yan and Sautman Citation2012) and so that allegation remains anecdotal.

Chinese Managers, African Workers

Continuing with the theme of labor, we survey the literature to evaluate the kind of employment which Chinese investments offer to local Africans. Although Chinese firms’ high labor localization rate across many African countries is not in doubt and in some cases locals have risen to occupy top managerial positions (Sun, Jayaram, and Kassiri Citation2017; X. Tang Citation2019a), the literature is replete with instances of locals occupying low-skilled or at best mid-level positions in Chinese firms. This shows a discrepancy between employment generation and management participation, the negative implication being low locally taxable incomes and low local input into Chinese companies’ economic activities (Warmerdam and van Dijk Citation2013). Most skilled and upper-level management positions tend to be occupied by the Chinese: for example, in multiple sectors in Angola and the DRC (X. Tang Citation2010); in the construction industry in Ghana (Meng and Nyantakyi Citation2019; Kernen and Lam Citation2014), or Tanzania and Zambia (Burke Citation2007); in the manufacturing industry in Rwanda (Eom Citation2018); in the catering industry in Zimbabwe (Njerekai, Wushe, and Basera Citation2018). Melissa Lefkowitz (Citation2017), conducting an ethnographic inquiry into CCTV Africa’s head offices in Kenya, reports that “per CCTV Africa’s policy, department supervisors were ubiquitously Chinese nationals” (2017, 9). Ward Warmerdam and Meine Pieter van Dijk (2013), studying the operations of forty-two Chinese enterprises in Uganda, “conclude that the vast majority of interviewed Chinese companies had no Ugandans in management, with only a quarter employing any Ugandans in management at all” (2017, 285). Sun, Jayaram, and Kassiri (Citation2017) find local managers in their survey of over 1000 Chinese-owned companies to be only 44%.

Explanations have been given for this low-local-managerial-position phenomenon, especially within the construction sector. Zhengli Huang and Xiangming Chen (Citation2016) state: “To be fair, on most construction sites in Africa, the majority of the labor force turns out to be local. But since infrastructure construction is labor-intensive and there is a chronic shortage of skilled labor in the local market, it is not surprising that many construction workers are sent from China” (2016, 10). Other explanations include the language barrier and the low integration rate of Chinese firms in the African construction sector (Chinese firms, compared to other foreign companies, are virtually new in Africa). Interestingly, however, data from a country case study do not support the assertions by Huang and Chen (Citation2016). In Ghana, Qingwei Meng and Eugene Nyantakyi (2019) empirically observe that although, on average, the share of skilled employees hired locally by Chinese-owned construction enterprises (86%) was lower than that of other foreign-owned enterprises (91%), both were, intriguingly, higher than that of locally-owned enterprises (78%). Of further relevance to our discussions, the study finds that whereas on average the share of supervisors hired locally by Chinese-owned enterprises was higher (57%) than that of other foreign-owned enterprises (35%), both were significantly lower than that of locally-owned enterprises (78%) giving credence to the claim that top management level positions are usually occupied by other foreign personnel.

The findings examined in this section beg the following question: are foreign enterprises from other emerging and developed countries different from Chinese enterprises in terms of the phenomenon of under-representation of local recruits in supervisory and top management level positions? Here the attempt by Zander Rounds and Hongxiang Huang (2017) to answer the question draws some insightful conclusions. They observe that the Chinese are not “so different” and that in American firms, even in companies that are predominantly Kenyan, executive roles and strategic decision-making tend to be still concentrated in the hands of the North American employees. Their findings equally reinforce the point that top-management level positions are the preserve of the Chinese. The key conclusion from the discussions on labor in this study is this: in a typical large or medium-scale Chinese firm in Africa (not less than 100 employees) one will likely find more than 80% of the workers being locals; however the highly-skilled and/or top management level positions will be occupied by Chinese nationals.

Discussion and Conclusion

Over the past few decades, Afro-Chinese relations have grown steadily in all arenas—socio-economic, political, and development co-operation (Alden, Large, and Soares de Oliveira Citation2008)—with China increasingly becoming an important source of financial support for many African nations. Frequent diplomatic exchanges, pillared on past and present politico-economic alliances, have also strengthened the ties between the two. Their “developing country” tag also continues to shape their present alliance. However, while many African countries still struggle due to minimal industrialization coupled with huge deficits in infrastructure, the Chinese have succeeded in achieving a phenomenal economic rise. Therefore, many African states are now considering shackling their economic and political future to a Chinese lead precisely because of its demonstrable achievements and its perceived economic trajectory (Alden, Large, and Soares de Oliveira Citation2008). However, despite the fact that the African economic landscape continues to benefit from Chinese-funded infrastructure and industrial projects aimed at enhancing economic development, claims about the impact of China in Africa, often portrayed as a “Chinese scramble for Africa,” have fomented fear within Afro-Chinese engagement.

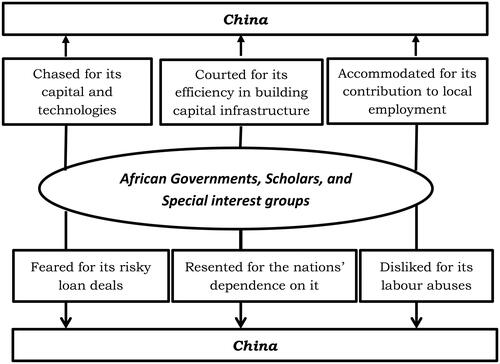

We argue that within African policy circles (governments, scholars, and special interest groups) the tensions between opposing perspectives on the value of the Sino-African business relationship have reached a crescendo. Having made explicit how Sinophilia and Sinophobia play out in practice, we assimilate the two perspectives to induce an integrative framework (), to delineate the affection/disaffection phenomena characterizing the evolving Chinese African business relationship.

First, some Chinese loan deals with African governments lack the necessary transparency to fit with the often touted “win-win” Afro-Chinese relationship; they have also been shown to be skewed in favor of Chinese interests. Second, although there are nuanced and sometimes good labor relationships between Chinese employers and African employees, empirical findings frequently reveal a worrying theme of labor abuses and Chinese entrepreneurs’ disregard for labor union regulations. Naturally, these disturbing revelations overshadow any positive Afro-Chinese undertakings. We therefore recommend that African public financial officials carefully strengthen their financial negotiation capacity in loan deals by involving civil society organizations and, if necessary, competent foreign financial firms in the transaction of such deals. The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) can also help in this regard. Ministers of finance and economic planning should co-ordinate and find mechanisms to superintend such huge financial transactions as the Sino-Congolese deal. Interventions must not always come from other foreign financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank as happened in the Sino-Congolese deal.

In discussing the flying geese model and the recent push by Chinese firms in Africa, it is helpful to note that legal Chinese businesses are proliferating alongside informal Chinese businesses in Africa, (cf. McNamee et al. Citation2012). Relative to other foreign-owned businesses in Africa, Chinese businesses, especially small businesses, are unique in their push towards the informal sector in Africa. For example, recent findings indicate a large proportion of informal Chinese small-scale mining operators in the extractive sector in Ghana, with their activities exacerbating the already high mining-induced environmental problems (Bach Citation2014; Ofosu et al. Citation2020; Crawford and Botchwey Citation2017). We note that these informal operations may be breeding grounds for labor abuses and unfair business practices as well. We therefore recommend that the various ministries of employment and their agencies should collaborate with their Chinese counterparts to identify these informal business operators. Once identified, flexible registration procedures should be initiated to enable these business operators to register their activities so that labor unions can monitor the operations and address any issues which may arise in the course of these Chinese business activities.

On a more Sinophilic note, it is apparent, first, that the Chinese are ready and willing to finance projects which are important to the long-term development prospects of African economies. The speed and lack of bureaucracy that China brings to the execution of infrastructure projects and the Chinese government’s readiness to collaborate with African governments to improve the financing of such projects is impressive. This dynamic underlines “the fact that China has been willing and able to fill notable gaps left by the more established donors in Africa” (Alden, Large, and Soares de Oliveira Citation2008, 11). Second, Chinese investment focus on good quality, low-cost, fast-delivery infrastructure—roads, bridges, and hydroelectric dams—has been monumental in bridging Africa’s infrastructure gap. These infrastructure developments, financed through soft loans, are making definite contributions to the improvement of African livelihoods.

In addition to the infrastructure developments, Chinese investments in human capital development—employment generation for local workers, skills training, and technological transfer—have been promising. Based on this and in light of the fact that most African governments, while prioritizing development and change, are still confronted with huge infrastructure and investment financing difficulties, we expect that the Afro-Chinese relationship will deepen now that traditional financiers from the West have largely retreated from funding infrastructure and investment enterprises in Africa. Although the Chinese quest for natural resources in Africa would eventually lessen (natural resources are depletable and alternative strategies for energy security abound [Jaffe and Lewis Citation2002]), a deepening of relations would persist as Chinese “geese” would continue to seek new market opportunities in a globally competitive industrial arena. Africa, with its ever-growing consumer market and low labor costs would therefore continue to serve as fertile ground for manufacturing and other investment activities from Beijing. Following significant Chinese investment in the upgrade of infrastructure in Africa, power and transport logistics costs would eventually reduce, resulting in the removal of some of the bottlenecks which discourage foreign and domestic investors from establishing factories in Africa. Significantly, Chinese “geese” (private firms and individual entrepreneurs) would perpetuate China’s deepening engagement with Africa, even if government-to-government ties begin to loosen.

However, we submit that the deepening of the relationship would largely require sound policy judgments based on the assessment of past and current investments. This is where Sino-African scholars could become increasingly useful. Going forward and for the furtherance of this study, scholars must focus more on the qualitative and quantitative micro-analysis of the impact on livelihoods in Africa of the Chinese-funded infrastructure projects. Such studies are important because some analysts describe the role of Chinese-funded infrastructure projects in Africa as based on political irrationality rather than sound economic investment. Similarly, we invite future research on Chinese investments in Africa to focus on examining how the upgrade in Africa’s infrastructure is facilitating the attraction of Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) into the African industrial arena and its consequential impact on human capital development. We also urge scholars to investigate the extent to which and sectors in which African entrepreneurs are employing the skills and technological education acquired from their Chinese counterparts in setting up their own businesses. Furthermore, this study observes that the use of the “flying geese” model to examine the impact of only Chinese firms on African industry overlooks another important group: non-Chinese foreign investors. Due to Africa’s colonial past, foreign and especially European firms are known to have established manufacturing industries and led the processes towards Africa’s industrial revolution, albeit minimally. Therefore, to elucidate the real and exclusive impact of Chinese investments in the industrial dynamism in order to inform policy, more comparative studies should examine the impact of Chinese “geese” vis-a-vis other foreign “geese” in the structural transformation of African industry. Finally, the question that drives this study reappears: Sinophilia or Sinophobia? Our aim is not to steer the discussion towards one of these positions. Rather, academics, policy makers, and governments interested in the Afro-Chinese relations should be aware of the existence of both phenomena and should take practical measures to maximize the positive impacts while minimizing the negative ones. Stable and economically sound African economies not only benefit African people but also the numerous Chinese firms and individual entrepreneurs scattered all over the continent.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

George Ofosu

George Ofosu is in the Center for International Development and Environmental Research at Justus Liebig University Giessen. David Sarpong is in the College of Business, Arts & Social Sciences at Brunel Business School, Brunel University, London.

David Sarpong

George Ofosu is in the Center for International Development and Environmental Research at Justus Liebig University Giessen. David Sarpong is in the College of Business, Arts & Social Sciences at Brunel Business School, Brunel University, London.

Notes

1 Refer to Brautigam and Gallagher (Citation2014) for estimates of the Chinese commodity-backed or resource-secured financing schemes in Africa and Latin America.

2 Specific focus on skills training and technology transfer, labor, and infrastructure

3 Specific focus on loans, and labor

4 The combined power generation of the forty-eight sub-Saharan African countries, with a combined population of close to 1 billion is approximately the same as the power generation capacity of Spain, with a population of 45 million (Foster and Briceno-Garmendia Citation2010). It is estimated that over US$90 billion would be needed to fill the infrastructure gap in Africa (Gutman, Amadou, and Chattopadhyay Citation2015).

References

- Adegoke, Yinka. 2018. “Chinese Debt Doesn’t Have to be a Problem for African Countries.” Available at https://qz.com/africa/1276710/china-in-africa-chinese-debt-news-better-management-by-african-leaders/ Accessed October 2, 2018.

- Ado, Abdoulkadre, and Zhan Su. 2016. “China in Africa: A Critical Literature Review.” Critical Perspectives on International Business 12 (1): 40–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-05-2013-0014

- Agbebi, Motolani. 2019. “Exploring the Human Capital Development Dimensions of Chinese Investments in Africa: Opportunities, Implications and Directions for Further Research.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 54 (2): 189–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909618801381

- Akamatsu, Kaname. 1962. “A Historical Pattern of Economic Growth in Developing Countries.” The Developing Economies 1 (1): 3–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1049.1962.tb01020.x

- Alden, Chris. 2007. China in Africa (African Arguments). Zed Books London.

- Alden, Chris, and Cristina Alves. 2008. “History and Identity in the Construction of China’s Africa Policy.” Review of African Political Economy 35 (115): 43–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056240802011436

- Alden, Chris and Martyn Davies. 2006. “A Profile of the Operations of Chinese Multinationals in Africa.” South African Journal of International Affairs 13 (1): 83–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10220460609556787

- Alden, Chris and Dan Large. 2011. “China’s Exceptionalism and the Challenges of Delivering Difference in Africa.” Journal of Contemporary China 20 (68): 21–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2011.520844

- Alden, Chris, Dan Large, and Ricardo Soares de Oliveira. 2008. “China Returns to Africa: Anatomy of an Expansive Engagement.” Elcano Working Paper 51.

- Alves, Ana C. 2011. “China’s Oil Diplomacy: Comparing Chinese Economic Statecraft in Angola and Brazil.” PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Alves, Ana C. 2013. “China’s ‘Win-Win’ Cooperation: Unpacking the Impact of Infrastructure-for-Resources Deals in Africa.” South African Journal of International Affairs 20 (2): 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2013.811337

- Anshan, Lin. 2007. “China and Africa: Policy and Challenges.” China Security 3 (3): 69–93.

- Atomre, Evelyn, Joel Odigie, James Eustace, and Wilson Onemolease. 2009. “Chinese Investments in Nigeria.” In Chinese Investments in Africa: A Labour Perspective, edited by Anthony Baah and Herbert Jauch, 366–383. African Labor Research Network (ALRN).

- Ayittey, George B. N. 2017. “Chinese Investments in Africa: Chopsticks Mercantilism.” Pambazuka News. Available at https://www.pambazuka.org/emerging-powers/chinese-investments-africa-chopsticks-mercantilism.

- Baah, Anthony Y,. and Herbert Jauch (eds.). 2009. “Chinese Investments in Africa: A Labour Perspective.” African Labour Research Network.

- Bach, Stangeland J. 2014. “Illegal Chinese Gold Mining in Amansie West, Ghana-An Assessment of its Impact and Implications.” Master’s Thesis, Universitet i Agder/University of Agder.

- Borojo, Dinkneh G., and Yushi Jiang. 2016. “The Impact of Africa-China Trade Openness on Technology Transfer and Economic Growth for Africa: A Dynamic Panel Data Approach.” Annals of Economics and Finance 17 (2): 403–431.

- Brautigam, Deborah. 2003. “Close Encounters: Chinese Business Networks as Industrial Catalysts in Sub-Saharan Africa.” African Affairs 102 (408): 447–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a138824

- Brautigam, Deborah. 2009.The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford University Press.

- Brautigam, Deborah, and Kevin P. Gallagher. 2014. “Bartering Globalization: China’s Commodity-backed Finance in Africa and Latin America.” Global Policy 5 (3): 346–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12138

- Brautigam, Deborah, and Jyhjong Hwang. 2019. “Great Walls Over African Rivers: Chinese Engagement in African Hydropower Projects.” Development Policy Review 37 (3): 313–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12350

- Brautigam, Deborah, Xiaoyang Tang, and Ying Xia. 2018. “What Kinds of Chinese ‘Geese’ Are Flying to Africa? Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms.” Working Paper No. 2018/17. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Brautigam, Deborah, Toni Weis, and Xiaoyang Tang. 2018. “Latent Advantage, Complex Challenges: Industrial Policy and Chinese Linkages in Ethiopia’s Leather Sector.” China Economic Review 48 (1): 158–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.06.006

- Breeze, Victoria, and Nathan Moore. 2017. “China has Overtaken the US and UK as the Top Destination for Anglophone African Students.” Quartz Africa.

- Burke, Christopher. 2007. “China’s Entry into Construction Industries in Africa: Tanzania and Zambia as Case Studies.” China Report 43 (3): 323–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000944550704300304

- Busse, Matthias, Ceren Erdogan, and Henning Mühlen. 2016. “China’s Impact on Africa–The Role of Trade, FDI and Aid.” Kyklos 69 (2): 228–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12110

- Campbell, Horace. 2008. “China in Africa: Challenging US Global Hegemony.” Third World Quarterly 29 (1): 89–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590701726517

- Carter, Becky. 2017. “A Literature Review on China’s Aid.” Helpdesk Report K4D. Brighton (UK): Institute of Development Studies.

- Chellaney, Brahma. 2017. “Sri Lanka the Latest Victim of China’s Debt-trap Diplomacy.” Asia Times. Available at www.asiatimes.com/2017/12/sri-lanka-latest-victim-chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy/ Accessed November 1, 2018.

- Chemingui, Mohamed A., and Mohamed H. Bchir. 2010. “The Future of African Trade with China under Alternative Trade Liberalization Schemes.” African Development Review 22 (s1): 562–576. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2010.00264.x

- Chen, Chuan, Pi-Chu Chiu, Ryan J. Orr, and Andrea Goldstein. 2007. “An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Construction Firms’ Entry into Africa.” Proceedings of the CRIOCM2007 International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate 8–13.

- Chen, Chuan, and Ryan J. Orr. 2009. “Chinese Contractors in Africa: Home Government Support, Coordination Mechanisms, and Market Entry Strategies.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 135 (11): 1201–1210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000082

- Chen, Wenjie, David Dollar, and Heiwai Tang. 2016. “Why is China Investing in Africa? Evidence from the Firm Level.” The World Bank Economic Review 32 (3): 610–632.

- Chen, Yunnan, and David Landry. 2016. “Capturing the Rains: A Comparative Study of Chinese Involvement in Cameroon’s Hydropower Sector.” Working Paper No. 2016/6. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Chen, Yunnan, Irene Y. Sun, Rex U. Ukaejiofo, Xiaoyang Tang, and Deborah Brautigam. 2016. “Learning from China? Manufacturing, Investment, and Technology Transfer in Nigeria.” Working Paper 2. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- China Africa Research Initiative (CARI). 2018. “Data: Chinese Loans and Aid to Africa.” Available at www.sais-cari.org/data-chinese-loans-and-aid-to-africa/ Accessed November 1, 2018.

- Corkin, Lucy and Christopher Burke. 2006. “China’s Interest and Activity in Africa’s Construction and Infrastructure Sectors.” Report prepared for DFID China. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Centre for Chinese Studies 37–39.

- Corkin, Lucy, Christopher Burke, and Martyn Davies. 2008. “China’s Role in the Development of Africa’s Infrastructure.” SAIS Working Papers in African Studies 04–08.

- Crawford, Gordon, and Gabriel Botchwey. 2017. “Conflict, Collusion and Corruption in Small-scale Gold Mining: Chinese Miners and the State in Ghana.” Commonwealth and Comparative Politics 55 (4): 444–470. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2017.1283479

- Dahir, Abdi L. 2018a. “China Now Owns More Than 70% of Kenya’s Bilateral Debt.” Quartz Africa. Available at https://qz.com/africa/1324618/china-is-kenyas-largest-creditor-with-72-of-total-bilateral-debt/ Accessed November 2, 2018.

- Dahir, Abdi L. 2018b. “Thanks to China, Africa’s Largest Free Trade Zone has Launched in Djibouti.”” Quartz Africa. Available at https://qz.com/africa/1323666/china-and-djibouti-have-launched-africas-biggest-free-trade-zone/.

- Dreher, Axel, Andreas Fuchs, Brad Parks, Austin M. Strange, and Michael J. Tierney. 2018. “Apples and Dragon Fruits: The Determinants of Aid and other Forms of State Financing from China to Africa.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (1): 182–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx052

- Eisenman, Joshua, and Joshua Kurlantzick. 2006. “China’s Africa Strategy.” Current History 105 (691): 219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2006.105.691.219

- Elu, Juliet U., and Gregory N. Price. 2010. “Does China Transfer Productivity Enhancing Technology to Sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from Manufacturing Firms.” African Development Review 22 (s1): 587–598. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2010.00260.x

- Eom, Janet. 2018. “Chinese Manufacturing Moves to Rwanda: A Study of Training at C&H Garments.” Working Paper No. 2018/18. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Eom, Janet, Deborah Brautigam, and Lina Benabdallah. 2018. “The Path Ahead: The 7th Forum on China-Africa Cooperation.” China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI), Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Washington D.C. Briefing Paper No 1.

- Farrell, Jamie. 2016. “How do Chinese Contractors Perform in Africa? Evidence from World Bank Projects.” Working Paper No.2016/3. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Foster, Vivien, William Butterfield, Chuan Chen, and Nataliya Pushak. 2009. Building Bridges: China’s Growing Role as Infrastructure Financier for Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank: Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility.

- Foster, Vivien, and Cecilia Briceno-Garmendia. 2010. Africa’s Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation (Overview). The World Bank.

- Gao, Jinyuan. 1984. “China and Africa: The Development of Relations over Many Centuries.” African Affairs 83 (331): 241–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097607

- Giese, Karsten. 2013. “Same-Same but Different: Chinese Traders’ Perspectives on African labor.” The China Journal (69): 134–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/668841

- Global Witness. 2011. “China and Congo: Friends in Need.” Global Witness, March 2011.

- Goethals, Samentha, Jean-Pierre Okenda, and Raphael Mbaya. 2009. Chinese Mining Operations in Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID), Action contre l’impunite pour les droits humains (ACIDH).

- Gu, Jing. 2009. “China’s Private Enterprises in Africa and the Implications for African Development.” The European Journal of Development Research 21 (4): 570–587. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2009.21

- Gutman, Jeffrey, Sy Amadou, and Soumya Chattopadhyay. 2015. “Financing African Infrastructure: Can the World Deliver?” Brookings, March 20, 2015.

- Haifang, Liu, and Jamie Monson. 2011. “10. Railway Time: Technology Transfer and the Role of Chinese Experts in the History Of TAZARA.” In African Engagements, edited by Ton Dietz, Kjell Havnevik, Mayke Kaag, and Terje Oestigaard, 226–251. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

- Huang, Zhengli, and Xiangming Chen. 2016. “Is China Building Africa?” European Financial Review 7

- Huang, Meibo, and Peiqiang Ren. 2013. “A Study on the Employment Effect of Chinese Investment in South Africa.” Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

- Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2011. You’ll be Fired if You Refuse: Labor Abuses in Zambia’s Chinese State-owned Copper Mines. Human Rights Watch.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2017. Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa; Restarting the Growth Engine. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

- Isaksson, Ann-Sofie, and Andreas Kotsadam. 2018. “Racing to the Bottom? Chinese Development Projects and Trade Union Involvement in Africa.” World Development 106 (1): 284–298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.003

- Jaffe, Amy M., and Steven W. Lewis. 2002. “Beijing’s Oil Diplomacy.” Survival 44 (1): 115–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00396330212331343282

- Jiang, Wenran. 2009. “Fueling the Dragon: China’s Rise and its Energy and Resources Extraction in Africa.” The China Quarterly 199 (1): 585–609. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741009990117

- Johnston, Lauren A., and Robert J. Earley. 2018. “Can Africa Build Greener Infrastructure while Speeding up its Development? Lessons from China.” South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA)-Occasional Paper 292.

- Kabemba, Claude. 2016. “China-Democratic Republic of Congo Relations: From a Beneficial to a Developmental Cooperation.” African Studies Quarterly 16.

- Kaplinsky, Raphael. 2013. “What Contribution can China Make to Inclusive Growth in sub-Saharan Africa?” Development and Change 44 (6): 1295–1316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12059

- Kaplinsky, Raphael, and Mike Morris. 2009. “Chinese FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa: Engaging with Large Dragons.” The European Journal of Development Research 21 (4): 551–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2009.24

- Kazeem, Yomi, and Abdi Latif Dahir. 2018. “China is Pushing Africa into Debt, says America’s Top Diplomat.” Quartz Africa. Available at https://qz.com/africa/1223412/china-pushes-africa-into-debt-says-trumps-top-diplomat-rex-tillerson/ Accessed November 1, 2018.

- Kernen, Antoine, and Katy N. Lam. 2014. “Workforce Localization among Chinese State-owned Enterprises (SOEs) in Ghana.” Journal of Contemporary China 23 (90): 1053–1072. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2014.898894

- Khan Mohammad, G. 2014.” The Chinese Presence in Africa: A Sino-African Cooperation from Below.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 43 (1): 71–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261404300104

- King, Kenneth. 2010. “China’s Cooperation in Education and Training with Kenya: A different Model?” International Journal of Educational Development 30 (5): 488–496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.03.014

- King, Kenneth. 2011. “China’s Cooperation with Ethiopia-With a Focus on Human Resources.” Ossrea Bulletin 8 (1): 88–113.

- Kirchherr, Julian, Tim Disselhoff, and Katrina Charles. 2016. “Safeguards, Financing, and Employment in Chinese Infrastructure Projects in Africa: The Case of Ghana’s Bui Dam.” Waterlines 35 (1): 37–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.2016.005

- Konings, Piet. 2007. “China and Africa: Building a Strategic Partnership.” Journal of Developing Societies 23 (3): 341–367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X0702300303

- Kuo, Lily. 2017. “Kenya’s $3.2 Billion Nairobi-Mombasa Rail Line Opens with Help of China.” Quartz Africa. Available at https://qz.com/africa/996255/kenyas-3-2-billion-nairobi-mombasa-rail-line-opens-with-help-from-china/ Accessed May 6, 2018.

- Kuo, Lily. 2018. “A Chinese-Built Bridge Collapsed in Kenya Two Weeks after it was Inspected by the President.” Quartz Africa.

- Lampert, Ben, and Giles Mohan. 2014. “Sino-African Encounters in Ghana and Nigeria: From Conflict to Conviviality and Mutual Benefit.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 43 (1): 9–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261404300102

- Lee, Ching K. 2009. “Raw Encounters: Chinese Managers, African Workers and the Politics of Casualization in Africa’s Chinese Enclaves.” The China Quarterly 199 (1): 647–666. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741009990142

- Lefkowitz, Melissa. 2017. “Chinese Media, Kenyan Lives: An Ethnographic Inquiry into CCTV Africa’s Head Offices.” Working Paper No. 2017/9. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Lekorwe, Mogopodi, Anyway Chingwete, Mina Okuru, and Romaric Samson. 2016. “China’s Growing Presence in Africa Wins Largely Positive Popular Reviews.” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 122.

- Lin, Justin Y. 2011. “From Flying Geese to Leading Dragons: New Opportunities and Strategies for Structural Transformation in Developing Countries.” World Bank, Policy Research Working Papers.

- Marysse, Stefaan, and Sara Geenen. 2009. “Win-Win or Unequal Exchange? The Case of the Sino-Congolese Cooperation Agreements.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 47 (3): 371–396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X09003978

- Marysse, Stefaan, and Sara Geenen. 2011. “Triangular Arm Wrestling: Analysis and Revision of the Sino-Congolese Agreements.” In Natural Resources and Local Livelihoods in the Great Lakes Region of Africa, Springer, 237–251. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McDonald, Kristen, Peter Bosshard, and Nicole Brewer.2009. “Exporting Dams: China’s Hydropower Industry Goes Global.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (3): S294–S302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.07.023

- McNamee, Terence, Greg Mills, Sebabatso Manoeli, Masana Mulaudzi, Stuart Doran, and Emma Chen. 2012. Africa in Their Words: A Study of Chinese Traders in South Africa, Lesotho, Botswana, Zambia and Angola. The Brenthurst Foundation.

- Men, Tanny. 2014. “Place-based and Place-bound Realities: A Chinese Firm’s Embeddedness in Tanzania.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 43 (1): 103–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261404300105

- Meng, Qingwei, and Eugene B. Nyantakyi. 2019. “Local Skill Development from China’s Engagement in Africa: Comparative Evidence from the Construction Sector in Ghana.” Working Paper No. 2019/22. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, John Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Mohan, Giles. 2013. “Beyond the Enclave: Towards a Critical Political Economy of China and Africa.” Development and Change 44 (6): 1255–1272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12061

- Mohan, Giles, and Ben Lampert. 2013. “Negotiating China: Reinserting African Agency into China–Africa Relations.” African Affairs 112 (446): 92–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/ads065

- Morangi, Lucie. 2015. “Rail Project an Engine of Learning.” China Daily Africa, July 10, 2015.

- Morrison, Wayne M. 2019. China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States. Congressional Research Service Washington, DC.

- Njerekai, Cleopas, Rudorwashe Wushe, and Vitalis Basera. 2018. “Staffing and Working Conditions of Employees in Chinese Restaurants in Zimbabwe: Justifiable?” Journal of Tourism and Hospitality 7 (341): 2167–0269.

- O’Brien, Liam M. 2016. “With Those Views, You Should Work for the Communist Party of China: Challenging Western Knowledge Production on China-Africa Relations.” African East-Asian Affairs, Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch University (4).

- Ofosu, George, Andreas Dittmann, David Sarpong, and David Botchie. 2020. “Socio-economic and Environmental Implications of Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) on Agriculture and Livelihoods.” Environmental Science and Policy 106 (April): 210–220 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.02.005

- Ofosu, George, and David Sarpong. 2021. “The Evolving Perspectives on the Chinese Labour Regime in Africa.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, July 13, 2021.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2012. Mapping Support for Africa’s Infrastructure Investment. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Otoo, Nyarko K., Nina Ulbrich and Prince Asafu-Adjaye. 2013. Unions can Make a Difference: Ghanaian Workers in a Chinese Construction Firm at Bui Dam site. Trade Union Congress, Accra, Ghana; Trade Union Solidarity Centre, Helsinki, Finland.

- Ramo, J. C. 2004. The Beijing Consensus. Foreign Policy Centre.

- Reuters. 2010. “Congo Republic Hails Successful Dam Turbine Test.” Available at: www.reuters.com/article/ozabs-congo-republic-dam-20100129-idAFJOE60S0HW20100129

- Rotberg, Robert. 2015. “China’s Economic Slowdown Threatens African Progress.” The Conversation.

- Rounds, Zander, and Hongxiang Huang. 2017. “We are not so Different: A Comparative Study of Employment Relations at Chinese and American Firms in Kenya.” Working Paper No. 2017/10. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC.

- Rui, Huaichuan, Miao Zhang, and Alan Shipman. 2016. “Relevant Knowledge and Recipient Ownership: Chinese MNCS’ Knowledge Transfer in Africa.” Journal of World Business 51 (5): 713–728. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2016.07.009

- SACE. 2014.Business Perception Index Kenya - 2014: Chinese Companies’ Perception Survey of Doing Business in Kenya. SinoAfrica Centre of Excellence Foundation.

- Sanfilippo, Marco. 2010. “Chinese FDI to Africa: What is the Nexus with Foreign Economic Cooperation?” African Development Review 22 (S1): 599–614. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2010.00261.x

- Sanghi, Apurva, and Dylan Johnson. 2016. Deal or No Deal: Strictly Business for China in Kenya? The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 7614.