Abstract

Suggesting socio-cultural values are selectors of institutions and institutional practices, and institutions in turn are selectors of (economic) behaviors, we investigate what explains the persistence of institutions that were aligned with past socio-cultural values when the values subscribed to in society have fundamentally changed. What, in other words, explains the persistence of obsolete institutions? We do so by investigating the labor market situation for academics in post-communist societies in Europe.

Institutions shape the economy and its dynamics through the shaping of behaviors of actors in the economy (cf. Dolfsma Citation2019). Institutions constrain, and they also enable or even stimulate behaviors—for instance because institutions can constitute incentives. Institutions themselves, in turn, need to be in line with underlying socio-cultural values (cf. Dolfsma and Verburg Citation2008). What is more, conceptually, we argue here that socio-cultural values can be seen as the societal selection mechanism for institutions. In this line of thinking, institutions that do not fit the overall socio-cultural values dominant in society would be expected to not survive.

The conception of institutions that we put forward is favored also by Geoffrey Hodgson (Citation2004, 424) who describes institutions as: “durable systems of established and embedded social rules that structure social interactions.” This approach is situated in the original institutional conception of the institution that recognizes a stratified ontology, which consists of, for example, individuals, groups, institutions, communities, and systems of institutions. Not including a reference to socio-cultural values in a definition of institutions allows, conceptually, for potential non-alignment between institutions in society and the values pre-dominantly subscribed to (cf. Bush Citation2009).

It is argued that an economic system should not be conceived of as a pure system, devoid of system-foreign institutions without impurities (Hodgson Citation1999; Dolfsma, Finch and McMaster et al. Citation2005). Some would argue that this certainly did not hold for capitalism as an economic system. Historical and anthropological insights about economic development point to the constituting role of collective norms and values in economy and society (cf. Dolfsma and Spithoven Citation2008). In many cases economic and non-economic values and norms get intertwined. Gifts and markets as institutions can be seen as governed by different rules and norms—having gift exchange as part of a market economic system bring impurities into it. Markets cannot then per se be interpreted just as a place where exchanges take place. In terms of the argument that any given institutional setting is aligned with supporting socio-cultural values, impure elements in society pose conceptual challenges. When the impurities, however, pertain to a key part of society, rather than a relatively peripheral practice,Footnote1 and when the supporting socio-cultural values for society contrasted with the impurity are quite fundamental, a serious conceptual challenge is posed for institutional economists. How can the persistence of divergent and potentially obsolete institutions beyond a transition phase be explained?

In this article, the impurities generally referred to are, one would argue, core to an economy, pertaining as they do to the functioning of the (academic) labor market. In this article, we investigate how non-capitalist institutions, lined up with anti-capitalist socio-cultural values, persisted even at the heart of a functioning capitalist economy. We do so by investigating the institutional changes in the academic labor market of a country in the former communist hemisphere: Romania.

Society and Market as Evolving Evolutionary Systems

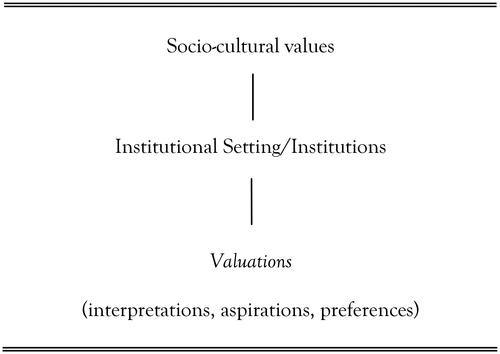

Behavior, including economic behavior, is governed by institutions relevant for the larger practice of which the behavior is part. As such institutions curtail certain behaviors, but also allow for behaviors. It is institutions that exert evolutionary selection pressure explaining what behaviors persist, and in what form. Institutions exert their evolutionary selection with reference to what the behaviors mean with respect to values underlying a practice (Dolfsma and Verburg Citation2008). See .

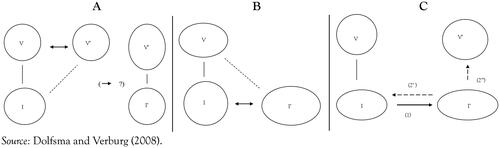

In this sense, the socio-cultural values, by allowing for what institutions to exist in society, can be thought of as exerting an evolutionary selection process on institutions. Wilfred Dolfsma and Rudy Verburg (2008) have conceptually elaborated on how institutional change might be emerging—see for reference. A new socio-cultural values-set might come to rival an incumbent set, prompting institutional change from I to I’. This is depicted in panel A. Panel B depicts a situation where a different institutional setting (I’), potentially consistent with an existing socio-cultural values-set V might rival existing institutional setting I. Either I or I’ might persist. Panel C of depicts a situation in which an existing V-I constellation is rivalled by a different V’-I’ constellation: different institutions to order a given practice, but also with different socio-cultural values in support of them. Either V-I or V’-I’ would be suggested to persist for the practice at hand, but not both.

Figure 2. Societal Values and Their Relation to Institutions: (A) Clashing Values, (B) Emerging Institutions, and (C) Clashing Practices

Perceiving of institutional systems, such as markets but also other parts of society, as themselves evolving and subject to evolutionary pressures, guided by what socio-cultural values are referred to, could provide a useful lens through which to understand societal change. The challenges that post-communist countries have faced when transitioning to a market economy can be characterized as one where both a set of socio-cultural values were introduced that were different from the ones in place before (V’), as well as, wholesale for many practices and particularly the core ones, institutions were introduced to align with this V’ socio-cultural values (I’). Panel C in seems to portray the relevant situation, conceptually, for institutional change in these circumstances.

Only Emile Durkheim (Citation[1893] 1997) paid attention to this; in his famous Division of Labor he discusses the evolution of societies, particularly the transition away from community-based systems such as communalism, socialism, or communism, introducing the concept of “institutional anomie.” Anomie is used as a metaphor for institutional change and evolution: when socio-economic systems change there are profound changes in institutions and cases where the formal institutions per se are not followed. Durkheim predicts that, as society is based on the dominance of economic (e.g., values) over non-economic (values), class conflicts and other conflicts such as gendered pay gaps on the labor markets would emerge. Each system requires, however, changes at the level of their institutional structure to find alignment. The Durkheimian Institutional Anomie Theory (IAT) has subsequently been used in criminological studies to explain how economic dominance over non-economic values and institutions tend to stimulate high levels of crime (see, for instance, Hovermann and Messner Citation2021. This article will use the IAT view for analyzing institutional change in the context of transformation towards capitalism and the resistance to change thereof, as applied to certain traits of the academic system in Romania.

Labor Markets: Cases of Obsolete Selection Systems

The labor market situation in academia is one that has persisted, at national or regional levels, for a long time. In Europe, for instance, countries or language areas have quite distinct systems to hire, promote, and fire or retire academics. These systems are broadly in line with Western, capitalist-style socio-cultural values in which merit is acknowledged and rewarded, fairness is appreciated, however: at V-level there is some variation, but limitedly so. The following offers an eclectic presentation of the Higher Education landscape—comprising both teaching and in particular research—in Romania. In order to bring out peculiarities we do so with reference to concepts from , on the one hand, and through a comparison with the situation in the UK.

Labor markets in academia do vary, of course, in the way in which these socio-cultural values are expressed in particular institutions.Footnote2 To what extent and in what way is research (as different from teaching and administration) recognized and rewarded? Can one build a career based on excellence in teaching, or as an administrator? How is excellent research measured?—do books count, chapters in edited volumes, articles in journals, or perhaps in some selected journals only? Differences can be spotted, but the different institutional settings are all consistent with the same set of socio-cultural values.

We present the labor market for academics in the formerly communist Romania as a case in point of an institutional setting building on socio-cultural values from communist times persisting despite a larger society’s shift to a very different, and opposing, socio-cultural value constellation. Better understanding of the persistence of such an institutional setting will help us better understand processes of institutional change in general. Since 1990, the point of Romanian transformation into a transition and then subsequently a capitalist economy, there has been a lot of economic and social turbulences. Periods of low and high inflation and unemployment have alternated, and major legislative changes have been staged, that have each affected the growth rate of the Romanian economy. Tsonugui Belinga, Butcher and Valerio (2020) summarize eloquently, reviewing relevant literature, the way that the Romanian labor markets has revolutionized in recent decades. Highlights are, first, the continuous migration flows and related skill levels at individual, local, regional, and national levels. Second, discomfort of Romanian peoples with the labor conditions—especially the salary rates. Third, the rapid changes in technology and the rapid evolution of markets. The COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, has brought forward a need for the workforce to be flexible in terms of acquiring new sets of skills, coping with unemployment, and technological changes. This, of course, is linked with the education system and how it can enable new skills for students, who can then become responsible employees and respond better to employers’ needs. The labor market for the country as a whole, therefore, is linked very directly to the labor market for academics themselves.

In the Romanian educational system, several levels can be distinguished, each with their own perspective. There is the Ministry of Education (national level), as part of a (now, in the post-communist era) elected government (central level). In addition, there is the local level (based on inspectorates and local schools).Footnote3 The national system of education has an open and flexible character, especially for pupils and students who can change their specialty, and respects the rights of the education of ethnic minorities (Tsoungui Belinga, Butcher and Valerio Citation2020). The public Higher Education institutes are free as is participation in the higher education system, based on the Bologna agreement, comprising of Bachelor, Master and PhD/Doctoral Studies. In terms of socio-cultural values, the Romanian academic system has understood the need for appropriate skills for the employers, especially critical thinking and coping with uncertainty and changes in the labor market, that contribute to competitiveness and economic growth. What has been criticized by employers regarding pedagogy is the overly theoretical content of the curriculum, absence of practical skills, a very good knowledge of foreign languages, and low participation by adults in continuous learning.

The education has been characterized as “utilitarian,” emphasizing the socio-cultural values of universalism and positivism (emphasizing generally applicable knowledge in combination with abstract transferable skills) over such values as contextual knowledge and societal impact. In general, emphasizing the (capitalist, at least enlightenment-related) socio-cultural value merit over loyalty may be seen as a positive development.Footnote4 When it comes to research, many universities and departments have adopted different specific (I’) tools of incentivizing research through a close annual monitoring: reports that need to be sent to the heads of department, deans, and research vice-rector following specific instructions about how to present information. Each member of academic staff has to showcase yearly a certain number of points based on status (assistant professor, reader, lecturer, and so onFootnote5)—the failure to do so brings extra hours of teaching, potentially creating a vicious circle in terms of producing research. The ISI Thompson Reuters classification of academic journals is adopted as a guide for research excellence: particularly journals in the higher “yellow” (light gray) and “red” (dark gray) categories from that list are noted. This contrasts with the British system that tends to use Association of Business School (ABS) system of ranking journals. While both prioritize publications in academic journals over other types of publications,Footnote6 a difference is that institutionalized “prices” for journal publications differ between systems. What is more, the way in which the ranking is used differs, signaling an (I) choice—in Romania it is used at the level of individuals, every year, during their entire career, yet in the UK when individual academics at a research-active Higher Education Institute are beyond “probation,” when they need to publish a fixed number of articles from categories in the ABS journals list, the metrics are applied at group or department level only. Another (I) choice related to how indicators of academic merit are used, is to which claims to fame individuals are entitled. In Romania, most research projects which are run in the university or funded by public institutions are conditioned by outputs on the Thompson Reuters list by members of the academic group who have proposed the project in the first place. Value to a research proposal is awarded based on past merit of outputs rather than present merit of ideas. Heterodox economic academics, adhering to a degree to different socio-cultural values when it comes to perceived quality of academic work because of being more inclined to favor contextual knowledge, societal impact, rather than universal knowledge claims, have been slow in the (I)-inspired journals ranking game (see Lee Citation2009). In large part because academic merit was increasingly ascribed to individuals and groups based on measurement of specific publications, with the exception of some departments, especially in business schools, heterodox economists for a while, at least, were marginalized (Lee Citation2009). It should be no surprise, given the (I)-choices made to reflect socio-cultural values for science, that in the Romanian system we detect a lack of interest in heterodox economics, although there is a variety of theories that would bring highly relevant and feasible policy solutions.

Related to teaching, the major differences can be identified when it comes to the structure of the academic year, which impacts the research capacity of academic staff. At the universities of Cambridge or Oxford teaching terms last eight weeks. Other “old/established universities” have ten week teaching cycles, and “new universities” have twelve weeks of teaching. There are two cycles of teaching each academic year. The Romanian system of higher education adopts fourteen weeks/semester in business studies, and it involves a high number of supervising dissertations. In the British system, the academic break would take place between May and October to be able to do research, while in the Romanian academic system the time left is literally the month of August and one to two weeks in September each year. Time being an obvious ingredient in producing research output, less time means fewer opportunities for research. A relatively strong emphasis (I) on teaching, in the national language rather than the lingua franca of academia (i.e., English) signals the need value of teaching to offer contextual understanding and impact. At the same time, this is at odds with imposing on academics the requirement to publish internationally—the international community does not understand the specificities of data concerning the countries concerned, on the one hand, and on the other hand no resources are made available to academics to acquire the connections and inputs necessary for internationally active research. As research output expectations increase, predatory publishers can make cunning use of this situation by offering a quick and relatively straightforward way out for the academic.

Concluding Thoughts: When would Evolution Promote Backwardness

In this brief article we have focused on how the Romanian academic system in general, and labor market in particular, has changed in post-communist decades. The Romanian academic system in part reflects the “new” socio-cultural values, but also at its core aligns partly with communist times’ socio-cultural values in a way that is at odds with the newly ascribed to values. As such, signals (incentives) to academics in Romanian academia can be confusing, both when its concerns research and for teaching. These are clear examples of clashes between institutions that attempt to regulate research production, imposing rules that seek to promote national research to meet international standing in rankings that reflect universalist socio-cultural values. This is at the expense of finding expression for research and teaching to emphasize and build contextual understanding and seek societal impact. In countries where resources are scarce, such tensions are felt even more acutely, even when the tensions are felt in academia globally.

As a final thought we would like to suggest, but not elaborate on and only partly drawing on our empirical illustration, answers to the question: what explains the persistence of obsolete institutions (institutions that do not align, or are even at odds with, pre-dominant socio-cultural values in society)? We submit that:

New socio-cultural values are shared by most, but not by all, participants, akin to Durkheimian “anomie.”

Not sharing socio-cultural values subscribed to broadly by others in the community can be for different reasons, including self-interest.

Socio-cultural values are not fully deterministic of what institutions align with them, leaving room for institutional entrepreneurs to find or create additional “wiggle room” that suits them (see Maguire, Hardy and Lawrence Citation2004; Munir and Phillips Citation2005).

Institutions do not fully prescribe what behaviors actors are to show (see Dolfsma, Finch and McMaster Citation2011).

Institutional settings may (necessarily) contain important “impurities” to persist.

Potentially as an institutional setting is “surrounded” by other institutional settings regulating practices in ways that need accommodation.

In particular, formal and informal institutions can be at odds (cf. Olthaar et al. Citation2017).

It is clear that these suggestions require further discussion, empirical support and conceptual elaboration.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ioana Negru

Ioana Negru is at the University of Sibiu, Romania, on the Faculty of Economic Sciences.

Wilfred Dolfsma

Wilfred Dolfsma is at Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands, Business Management and Organization group.

Notes

1 A practice is “any form of activity specified by a system of rules [(set of) institutions] which defines offices, roles, moves, penalties, defenses, and so on, and which gives activity its structure” (Rawls Citation1955, 3).

2 We refer to these as variations at the level of “I,” here sometimes referred as (I) choices.

3 This paragraph is based on “Romania Overview” (Citationn.d.).

4 The structure of economics textbooks would be, in pre-capitalist times, in which, by theme, the views of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and, finally as a way of concluding the discussion, former Romanian party-chair Ceausescu would be presented. Being able to loyally reproduce and support the views in detail of the leader of one’s immediate reference community was rewarded.

5 Before becoming a full professor in the Romanian academic system, it is necessary to produce a habilitation thesis that links four selected, necessarily Thomson Reuter’s ISI-listed publications from the indicated journal list and to defend their coherence and message publicly—an influence from the pre-communist, German HE system, but also creating room for academics to (be expected to) show the socio-cultural value of loyalty.

6 Books or chapters in books or presentations at conferences do not count, or much less, unless these are published by established publishers such as Routledge, Edward Elgar, Palgrave Macmillan, or an established University Press.

References

- Bush, Paul D. 2009. “The Neoinstitutionalist Theory of Value.” Journal of Economic Issues 43 (2): 293–306.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred. 2004. Institutional Economics and the Formation of Preferences. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred. 2019. “Institutionalized Communication in Markets and Firms.” Journal of Economic Issues 53 (2): 341–348.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, John Finch, and Robert McMaster. 2005. “Market and Society: (How) Do They Relate, and Contribute to Welfare?” Journal of Economic Issues 39 (2): 347–356.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, John Finch, and Robert McMaster. 2011. “Identifying Institutional Vulnerability: The Importance of Language, and System Boundaries.” Journal of Economic Issues 45 (4): 805–818.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, and Antoon Spithoven. 2008. “Silent Trade and the Supposed Continuum between OIE and NIE.” Journal of Economic Issues 42 (2): 517–526.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, and Rudy Verburg. 2008. “Structure, Agency and the Role of Values in Processes of Institutional Change.” Journal of Economic Issues 42 (4): 1031–1054.

- Durkheim, Emile. (1893) 1997. La Division du Travail Social/The Division of Labor in Society. New York: Free Press.

- Hodgson, Geoffrey M. 1999. Economics and Utopia. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hodgson, Geoffrey M. 2004. The Evolution of Institutions: Agency, Structure and Darwinism in American Institutionalism. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hovermann, Andreas and Steven F. Messner 2021. “Institutional Imbalance, Marketized Mentality and The Justification of Instrumental Offences: A Cross National Application of Institutional Anomie Theory”, Justice Quarterly 38 (3): 406–432.

- Lee, Fred S. 2009. A History of Heterodox Economics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Maguire, Steve, Cynthia Hardy, and Thomas B. Lawrence. 2004. “Institutional Entrepreneurship in Emerging Fields: HIV/AIDS Treatment Advocacy in Canada.” Academy of Management Journal 47: 657–679.

- Munir, Kamal A., and Nelson Phillips. 2005. “The Birth of the ‘Kodak Moment’: Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Adoption of New Technologies.” Organisation Studies 26 (11): 1665–1687.

- Olthaar, Matthias, Wilfred Dolfsma, Clemens Lutz, and Florian Noseleit. 2017. “Markets and Institutional Swamps: Tensions Confronting Entrepreneurs in Developing Countries.” Journal of Institutional Economics 13 (2): 243–269.

- Rawls, John. 1955. “Two Concepts of Rules.” The Philosophical Review 64 (1): 3–32.

- “Romania Overview.” n.d. European Commission: Eurydice. Available at https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/romania_en. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Tsoungui Belinga, Vincent, Neil Butcher, and Alexandra Valerio. 2020. “Addressing Romania’s Skills Deficit to Keep Pace with an Evolving Labor Market.” Brookings, July 23, 2020. Available at www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/07/23/addressing-romanias-skills-deficit-to-keep-pace-with-an-evolving-labor-market/. Accessed January 12, 2022.