Abstract

This article explores whether the EU’s new economic development model of competitive sustainability could serve as a blueprint for ecologically sustainable development models for advanced economies in general. To this end, we first discuss theoretically the interplay between competitiveness and sustainability and identify several challenges for combining them. In delineating different interpretations of competitive sustainability, we emphasize that operationalizing the concept requires deliberate design of the institutions governing competition so that it can contribute to sustainability. We substantiate our claim by using input-output data to analyze whether the identified challenges are indeed relevant. We conclude that they are, and propose possible solutions.

For several decades, economic policy-makers as well as scholars have trusted in measures such as growth and productivity. However, the ongoing climate crisis has led many to question these measures as policy goals in themselves. The European Commission, for instance, explicates in their Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy of 2020 that “[a]n economy must work for the people and the planet” (European Commission Citation2019, 1). If economies took environmental limits seriously, however, a re-thinking of their overall development model would become necessary. The new European Commission has delineated such an alternative development model, which is meant to address the challenges of climate change and maintain standards of living. At the core of this model lies the combination of two concepts: competitiveness and sustainability. Together, as competitive sustainability, they are meant to serve as the foundation of the EU’s new development model that puts a special focus on sustainability. First initiatives associated with this new model were the adoption of the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 Package, a set of proposals to revise EU legislation to achieve the central climate goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% until 2030.

The aim of the present article is to critically investigate the concept of competitive sustainability and its transformative potential from an institutionalist perspective, and to assess to what extent—and under which conditions—it can serve as a role-development-model for other “advanced” economies by taking both planetary boundaries and social justice considerations seriously. To this end we proceed as follows: in the next section we discuss the conceptual relationship between competitiveness and sustainability and identify conceptual challenges, which may lead to tangible frictions depending on the operationalization of competitive sustainability in actual policy making. The next section highlights the empirical relevance of one such challenge: the potential externalization of environmental costs by some countries to sustain their own sustainability and competitiveness. The final section, then, discusses the implications for how the European development model would need to be operationalized if it was useful as a viable development model for advanced economies.

Competitiveness, Sustainability, and Competitive Sustainability: Conceptual Pre-Considerations

Aside from a euphonious political slogan, the meaning of competitive sustainability is not entirely clear. We, therefore, first discuss the two central elements—competitiveness and sustainability—and then study their relation and potential challenges in operationalizing the strategy of competitive sustainability.

Competitiveness is a malleable concept, the precise meaning of which is subject to political struggles (e.g., Linsi Citation2020; Gräbner-Radkowitsch and Hager Citation2021). In any case, it only makes sense in relation to its underlying process: competition. Competition, in turn, is a social process that involves at least two parties that compete for a (naturally or artificially) scarce good (Altreiter et al. Citation2020). This interaction is structured by social institutions that provide a mechanism to resolve this conflict in a non-violent way, that is, by linking the allocation to the relative performance of the competitors according to some (explicitly or implicitly) defined performance measures. Competitiveness, then, denotes the relative performance capacity of one of these actors and may correspond to an asset, a capability or a property. Thus, competitiveness is a relative concept: an actor’s competitiveness can only be determined in relation to others, and an increase in the competitiveness of one actor necessarily comes with a decrease in the competitiveness of other actors.Footnote1

Sustainability is usually defined as “the quality of being able to continue over a period of time” (Cambridge Dictionary Citation2022). In contrast to their competitiveness, the sustainability of an actor can be determined without reference to other actors—it is an absolute concept in the sense that it is not necessarily comparative. On the contrary, increasing the sustainability of one actor usually has a positive impact on overall sustainability and does not reduce the sustainability of others. What is more, in the EU policy discourse the term sustainability is most often used with reference to the sustainable development goals (SDGs), where it is stressed that sustainability calls for (globally) joint action that centers around the goal to enable the present generation of humans to meet their needs in a way that does not compromise the ability for future generations to do the same. That is, not only does an increase in the sustainability of an actor imply an indirect increase in sustainability of others via overall sustainability, but according to current policy discourse, coordination is a necessary precondition to achieve sustainability in the first place.

To summarize, while competitiveness is a relative concept that is based on competition, sustainability is absolute and requires coordination. Thus, it is not readily clear whether sustainability and competitiveness can be achieved simultaneously and, consequently, whether the combination of the two concepts as competitive sustainability is sensible. This is especially relevant in the context of an economic development model that is meant to respect ecological boundaries: while, in this context, the goal of becoming more sustainable relative to other countries is not in itself a problem, for competitive sustainability to work as an environmentally sustainable development model, it must ensure that its impact is to establish overall sustainability. This, for instance, would not be the case if there were feedback mechanisms that benefited countries as they themselves became more sustainable, and if there were simultaneously ways in which one country could increase its own sustainability at the expense of another.

Whether this challenge is relevant in practice depends on how the relation between competitiveness and sustainability is conceptualized in the concept of competitive sustainability. There are at least three ways of how this could be done. First, competitive sustainability can be understood as competing in sustainability: here, countries try to harness the process of competition to achieve individual sustainability. That is, countries compete with other countries for more sustainability. The second possible reading is sustainability as competitive advantage: here, countries aspire to become more sustainable in order to become more competitive. This link could originate, for instance, from the fact that the production of sustainable products became more economically attractive and sustainable production strategies directly translate into greater competitiveness in the global economy; or from particular institutions, for example, the legal obligation to pay fees for the emission during production processes. Again, sustainable production strategies would then translate into greater competitiveness on international markets. Thus, in all these cases, greater competitiveness is to be achieved via greater sustainability. In the third interpretation, competitive sustainability is understood as competitiveness despite sustainability: here, countries transform their economies toward greater sustainability without jeopardizing their competitive position on international markets. In this sense, competitiveness and sustainability appear as two separate goals; this poses the challenge to address and rule out any trade-off between the two goals.

All three interpretations can be found in the Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy 2020 of the European Commission (European Commission Citation2019). For instance, there are passages that clearly suggest the ultimate goal of competitive sustainability is greater overall sustainability: “It puts sustainability—in all of its senses—[…] at the center of our action” (European Commission Citation2019, 1).

Other passages, however, suggest that sustainability is merely a means for greater competitiveness: “[By] developing new technologies and sustainable solutions, Europe can be at the forefront of future economic growth and become a global leader in an increasingly digitalised world …” (European Commission Citation2019, 1).

And yet other passages suggest that the Commission follows the third interpretation in which sustainability and competitiveness are separate goals, for instance, when they emphasize the divergence between rich and poor regions due to technological change and the challenges caused by the energy transition “unless suitable measures are taken to boost regional competitiveness” (European Commission Citation2019, 10, italics added).

Although the three interpretations of competitive sustainability are different in meaning, they have similar implications if one is interested in improving upon overall sustainability: all imply the need for an appropriate institutional framework that incentivizes countries who wish to sustain or improve their competitiveness on international markets to transform their economies towards sustainability. In all cases, however, the combination of sustainability and competitiveness could, in principle, also undermine the success of such an endeavor if competitive sustainability was operationalized in a way that does not incentivize countries to contribute to overall sustainability (e.g., if countries were able to improve their own sustainability at the expense of the sustainability of others). The extent to which this challenge is relevant is an empirical question and depends on the institutions established to manage the competitive process.

Practical Relevance: The Case of Externalizing Environmental Stressors

This section studies empirically the extent to which the conceptual challenge just discussed, that is, the practice of countries to improve their own sustainability at the expense of others and, thereby, to jeopardize the goal of overall sustainability, is indeed relevant and how such practice could be identified. To this end we use data from the multi-regional input output (MRIO) table EXIOBASE3 (Stadler et al. Citation2018), which contains information about the emissions and flows of a wide variety of environmental stressors. For the sake of illustration, however, we focus on the global warming parameter GWP100, an aggregate measure for negative environmental impacts. A sustainable development model would mean that countries aim at reducing the overall stressors emitted to the environment measured in terms of their global warming potential. In what follows, we compare two different accounting styles and discuss their different implications as well as the consequences for the operationalization of competitive sustainability.

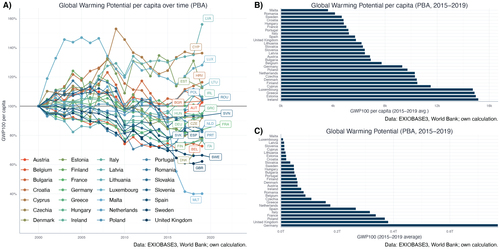

To begin, we employ the production-based accounting (PBA) approach to country-level environmental stressors, by attributing emissions to the area in which they are produced. presents the corresponding results for countries belonging to the EU28 (including the UK). This suggests the following conclusions: first, some countries in the EU achieved a relative reduction of environmental stressors, at least compared to the year 2000, while other countries increased their emissions. Second, the differences in absolute and per capita emissions are notable: countries with a larger population (such as Germany) tend to have higher overall emissions, but smaller emissions per capita. In any case, there are considerable differences among EU countries.

Figure 1. Total Emissions of the EU28

Note: Data and code to replicate the tables and figures of this article can be found at Gräbner, Hager, Hornykewycz (Citation2022) and Github.com (Citationn.d.). Emissions are measured by the production-based accounting approach. GWP100 is reported as an indicator that measures the energy absorbed by the emissions over 100 years in equivalents of CO2 emissions.

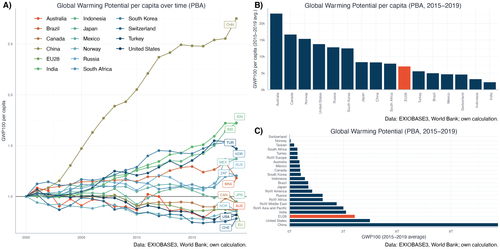

Adopting a global perspective, aggregates all European Member States into the EU28 category. It shows that some of the actors considered, including the EU28, managed to reduce their overall environmental impact as compared to the year 2000. Aside from the EU28, this includes mainly high-income countries; in several other countries total environmental stressors have increased. Looking at absolute figures, the EU28 has managed to achieve a lower-middle position in terms of per capita emissions, albeit it ranks third in terms of absolute emissions. This also shows that the EU is a relevant player in addressing the global climate crisis. In any case, the data suggest that at least some advanced countries are successful in reducing their overall impact (whether the speed of reduction is sufficient is a different question, though).

Figure 2. Total Emissions on a Global Level

Note: Data and code to replicate the tables and figures of this article can be found at Gräbner, Hager, Hornykewycz (Citation2022) and Github.com (Citationn.d.). Emissions are measured by the production-based accounting approach. GWP100 is reported as an indicator that measures the energy absorbed by the emissions over 100 years in equivalents of CO2 emissions.

While such a view at absolute emissions has been the standard method for accounting environmental stressors, and the default basis for environmental policy design, it has a significant drawback: it cannot capture the strategy of countries to improve their own sustainability at the expense of others by relocating economic activities to other countries and then importing the final goods, thus reducing the environmental stressor emitted on their own territory. As argued above, the challenge of the concept of competitive sustainability makes it susceptible to such externalizing behavior unless it is adequately institutionalized. To assess whether such behavior has been relevant in the context of the EU (and to outline strategies to identify and prevent it), we use the data from EXIOBASE3 to compute imported and exported emissions: imported emissions are those that occur in other countries for producing the goods and services consumed within the home country. For instance, if Germany imports wheat from Turkey, the imported emissions correspond to the emissions generated in Turkey during the production of the wheat to be delivered to Germany. Conversely, exported emissions are those generated domestically in the production of goods and services that are then sold to customers abroad. So, if China manufactures a solar panel that is shipped to the United States, then the emissions associated with the manufacturing process are accounted for as emissions exported by China. The difference between imported and exported emissions gives an indication whether a country is externalizing environmental stressors: if imports exceed exports, other countries tend to bear the environmental costs for the consumption activity at home.

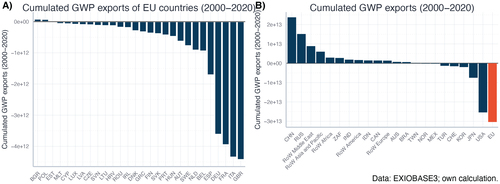

summarizes the results by aggregating environmental stressors over the period 2000–2020 (there have been little changes in the trends followed by individual countries) by showing the difference between imported and exported emissions (with a negative number representing emission imports). shows that while the vast majority of EU Member States are net emission importers, there are considerable differences between them: several EU countries show only very small or even no emission imports. Since, however, the emission importers are large in terms of their economies, and there are much more emission importers than exporters, the EU as a whole is still a significant net importer of environmental stressors (). This means that the environmental impact of the EU economy is underestimated if only its absolute emissions are considered (as done in ).

Figure 3. Emission Imports and Exports

Note: Data and code to replicate the tables and figures of this article can be found at Gräbner, Hager, Hornykewycz (Citation2022) and Github.com (Citationn.d.). Net emission exports are aggregated over the period 2000 - 2220. GWP100 is reported as an indicator that measures the energy absorbed by the emissions over 100 years in equivalents of CO2 emissions.

In all, this empirical application shows the following:

Within the EU, the majority of countries are persistent importers of environmental stressors, yet the degree is very heterogeneous across Member States.

The EU as a whole is a persistent and significant importer of emissions at the global level.

Both conclusions suggest that the conceptual challenge of competitive sustainability highlighted in the previous section is relevant—regardless of the interpretation adopted: there is a real danger that countries improve upon their own sustainability and competitiveness at the expense of the sustainability of other countries (and, thereby, at the expense of the system as a whole). While this does not indicate that the idea of competitive sustainability necessarily suffers from a fundamental inconsistency of the two concepts of competitiveness and sustainability, it does show that the EU must address this challenge and enact regulations to prevent such externalizing behavior in the future.

Discussion and Outlook

Based on the assertion that the current environmental crisis requires new development models to address future challenges, this article set out to discuss whether the EU’s proposal of competitive sustainability could be a viable option for advanced economies in general. This task was aggravated by the fact that the term competitive sustainability has multiple interpretations—all of which can be found simultaneously in the Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy 2020, the European Commission’s key document on the subject. Three of these interpretations have been discussed, and while they differ significantly in meaning, they all face one big challenge: the goal of overall sustainability may be compromised if countries can improve their sustainability by externalizing environmental costs to other countries with which they compete.

To avoid this, policy-makers must address the potential problem of externalization and beggar-thy-neighbor policies by institutionalizing “competitive sustainability” in a way that reconciles the principles of coordination and competition: competition can only contribute to increasing overall sustainability if the institutions that govern competition are agreed upon by the competing parties on a cooperative meta-level. This means that while countries can compete at the level of concrete economic interaction, they must cooperate to successfully coordinate on the rules of their competitive interaction. These rules must, inter alia, prevent the kind of competitive behavior that jeopardizes overall sustainability. Thus, for competitive sustainability to be effective, cooperation among the competing actors on an adequate institutionalization of their competition is mandatory.

While such an endeavor is difficult, it is by no means impossible. There exist a number of feasible measures or rules that prevent the externalization of environmental stressors. For instance, one could complement the classical production-based accounting and measure the sustainability of countries also by the so-called consumption-based accounting approach (CBA), where environmental stressors are not attributed to the geographical unit where the emission took place, but to the unit where the final product was consumed. This would make externalization attempts immediately visible, and their extent could even be regulated by the institutions governing competition themselves. A complementary strategy would be to set up strict border adjustment rules, or even strict limits on the emissions import surplus that countries may accumulate (see also, e.g., Wood et al. Citation2020). Finally, on a more general level, one could aim to collectively scale down consumption and production activities, a non-mainstream strategy advocated by degrowth-scholars and sufficiency-oriented policy programs (see, e.g., Zell-Ziegler et al. Citation2021).

Although the European Commission does not yet assess countries using the CBA, there are plans to implement a New Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) (European Commission Citation2021, Cazcarro et al. Citation2022). This suggests that, at least to some extent, the Commission is addressing the challenges identified in this article. As our analysis has shown, the implementation of such measures is crucial since competitive sustainability is not a panacea in itself. Only if its institutionalization is thoroughly deliberated, it could indeed be turned into a development model for advanced economies that takes planetary boundaries and social provisioning seriously.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch

Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch is assistant professor of pluralist economics at the Europa-University Flensburg, Germany, and research associate at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria. Theresa Hager and Anna Hornykewycz are research associates at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria. CGR and TH acknowledge funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under grant number ZK 60-G27.

Theresa Hager

Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch is assistant professor of pluralist economics at the Europa-University Flensburg, Germany, and research associate at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria. Theresa Hager and Anna Hornykewycz are research associates at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria. CGR and TH acknowledge funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under grant number ZK 60-G27.

Anna Hornykewycz

Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch is assistant professor of pluralist economics at the Europa-University Flensburg, Germany, and research associate at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria. Theresa Hager and Anna Hornykewycz are research associates at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria. CGR and TH acknowledge funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under grant number ZK 60-G27.

Notes

1 This, of course, does not imply that the process of competition cannot lead to all competitors being better off through the process of competition: the threat of mutual competition might, in principle, lead to an improved performance of all actors involved—despite decreasing competitiveness for some.

References

- Altreiter, Carina, Claudius Gräbner, Stephan Pühringer, Ana Rogojanu, and Georg Wolfmayr. 2020. “Theorizing Competition: An Interdisciplinary Framework.” SPACE Working Paper 4. Available at: https://spatial-competition.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/SPACE-WP4-CompetitionFramework1.pdf.

- Cazcarro, Ignacio, Diego García-Gusano, Diego Iribarren, Pedro Linares, José Carlos Romero, Pablo Arocena, Iñaki Arto, Santacruz Banacloche, Yolanda Lechón, Luis Javier Migue, Jorge Zafrilla, Luis-Antonio López, Raquel Langarita, María-Ángeles Cadarso. 2022. “Energy-Socio-Economic-Environmental Modelling for the EU Energy and Post-COVID-19 Transitions.” Science of The Total Environment 805: 150329. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150329.

- European Commission. 2021. “‘Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality.” COM/2021/550 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0550&from=EN.

- European Commission. 2019. Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy 2020. COM/2019/650 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0650&from=EN.

- Github.com. n.d. https://github.com/graebnerc/comp-sust23.

- Gräbner-Radkowitsch, Claudius, and Teresa Hager. 2021. “(Mis)Measuring Competitiveness: The Quantification of a Malleable Concept in the European Semester.” ICAE Working Paper 130. Available at: www.jku.at/fileadmin/gruppen/108/ICAE_Working_Papers/wp130.pdf.

- Gräbner-Radkowitsch, Claudius, Theresa Hager, Anna Hornykewycz, 2022, “Replication Data for: To Compete or not to Compete: An Institutionalist Analysis of the New Development Model of the European Union.” doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JD6VUQ, Harvard Dataverse.

- Linsi, Lukas. 2020. “The Discourse of Competitiveness and the Dis-embedding of the National Economy.” Review of International Political Economy 27 (4), 855–879. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1687557.

- Stadler, Konstantin, Richard Wood, Tatyana Bulavskaya, Carl-Johan Södersten, Moana Simas, Sarah Schmidt, Arkaitz Usubiaga, Josê Acosta-Fernández, et al. 2018. “EXIOBASE 3: Developing a Time Series of Detailed Environmentally Extended Multi-Regional Input-Output Tables.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 22 (3): 502–515. doi: 10.1111/jiec.12715.

- Cambridge Dictionary. 2022. “sustainability.” In The Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/sustainability. Accessed December 11, 2022

- Wood, Richard, Karsten Neuhoff, Dan Moran, Moana Simas, Michael Grubb, and Konstantin Stadler. 2020. “The Structure, Drivers and Policy Implications of the European Carbon Footprint.” Climate Policy 20 (sup1): S39–S57. Available at: doi: 10.1080/14693062.2019.1639489.

- Zell-Ziegler, Carina, Johannes Thema, Benjamin Best, Frauke Wiese, Jonas Lage, Annika Schmidt, Edouard Toulouse, and Sigrid Stagl. 2021. Enough? The Role of Sufficiency in European Energy and Climate Plans. Energy Policy 157: 112483. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112483.